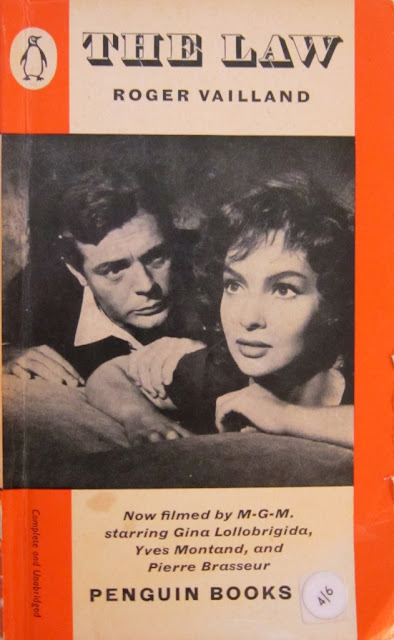

Roger Vailland, The Law: A Novel Set in Apulia, Trans. by Peter Wiles. Southern Italy, Jonathan Cape, 1958., Eland Books, 2004.

Now back in print, Roger Vailland's atmospheric 1957 novel won the Prix Goncourt, and the Knopf edition was a selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club. The grotesque game of the Law, played in the taverns of southern Italy, is but a shadow of an even fiercer attitude to life-a potent metaphor for a vigorously hierarchical view of existence which rules over the mezzogiorno, the noonday culture of southern Italy. In this novel we are not asked to pardon or condemn the passion of Donna Lucrezia, the assured self-centeredness of the learned aristocrat Don Cesare or even the sinister desires of Matteo Brigante, the controlling godfather."

The Law is an experience I will not easily forget. - V. S. Naipaul

The Law deserves every reading it will have. It is and does all that a novel should – amuses, absorbs, excites and illuminates not only its chosen patch of ground but much more of life and character as well." - New York Herald Tribune

It is one of the best novels I have ever read. - Alexander Chancellor

A brilliant study of the people, lifestyles and traditions of southern Italy… The hard, impoverished but passionate lives of a rural community are captured with precision. - Oxford Star w territory of Manacore, Pippo and his guaglioni were the only ones to escape the control of Matteo Brigante. One day battle would be joined: two gangs cannot exist in the same territory. But at the present time the gu Roger Vailland sets his story in the small Italian town of Porto Manacore, built on the Adriatic coast near the site of an ancient Greek city known as Uria which is now submerged beneath extensive marshlands. These marshlands provide a breeding ground for the mosquitoes which spread malaria amongst the local inhabitants, and those infected can be identified by their thin bodies, their feverish eyes, and their sallow skin. The antiques which the fishermen occasionally recover from the depths of the marsh, and the labourers from the olive groves, testify to a more prosperous past for the region, but it seems that only the old men are interested in this history; the youths of the town are more concerned with copying the trends and fashions of the north, viewed as a region of opportunity. Porto Manacore is a place from which people hope to escape.

This idea of a town built near a marsh which facilitates the spread of parasites, and near the ruins of a fallen civilization, seems to be used as a metaphor for the two factors suggested to dominate and constrain life in southern Italy in the years after the war. These are an almost feudal system of landownership which confers a bizarre set of rights upon a small number of landowners, and a pervasive system of organised crime which at one level seeks to control everything which occurs in the village and exact a tax on every transaction, and at another level manifests as petty crime and pickpocketing. These combine with a hierarchical social system and a set of values based on traditional ideas such as honour, and which establish norms which determine who in this society is beholden to whom.

The law referenced by the title has nothing to do with civil authority or the official laws of the region. There seems little concept in the society being described of a moral requirement to heed the laws of the land; such laws are viewed as requirements which have been imposed, and which can therefore be evaded. The very people charged with upholding the law, such as the chief of police and his deputies, are those involved in developing strategies for its evasion. They happily invent stories, fabricate evidence, and block investigations, in this case to assist the principal racketeer Matteo Brigante in his efforts to evade justice. He is a man proud of his hobby of raping virgins, and this is known by Chief of Police Atillo, whose own favourite pastime is seducing the wives of the town's leading citizens, making use of the racketeer's premises for his conquests. The two men often compare and contrast their respective pleasures and approaches, each quietly confident that he is the more virile.

However, it is difficult to pin down all that is being implied here by the notion of the law. At the simplest level the title is a reference to the game played each evening in the cafés of the Old Town, a game controlled, like everything else in Porto Manacore, by Matteo Brigante. It is a game of six or more players, played as a series of rounds, and in each round chance, in the form of dice or a drawn tarot card, determines which player will be the chief. He will choose another player as his deputy, and the others will supply a carafe of wine; the round ends when the carafe is drained. The chief behaves however he pleases: he may share the wine with the others or withhold it, and he may interrogate, slander, blame or praise them; his will is the law. A common strategy is to find the most vulnerable player and to humiliate him publicly, by referring to past indiscretions or current rumours, or by proposing some violation of a member of his family; he is required to endure it without flinching. It is the imposition of will which is appealing, the prospect of inflicting or observing the humiliation of another which affords them pleasure, and the possibility of demeaning someone higher in the hierarchy and untouchable in normal life which induces them to play.

But the law refers to more than this. It is a set of ideas and traditions embedded deep within the culture, which codifies obligations. It is a set of norms used to govern behaviour, but more importantly, it also establishes the benchmarks against which the behaviour of others can be judged. It is made clear that every one in the south of Italy is a jurist, ready to judge the others for their adherence to these unwritten rules and to impose them collectively through marshalling of town opinion, and it can encompass everything from the duty of a wife to submit to her husband's desires, to the unquestioned right of a landowner to take the virginity of every young woman in his household, irrespective of her own wishes. It is assisted by the claustrophobic nature of southern Italian life in which every action is observed and reported, and everyone concerns themselves with knowing the business of everyone else.

Roger Vailland tells the stories of several of the locals against this background of corruption and tradition, using their experiences to explore local attitudes and behaviours, and some of it is shocking. Women and young girls are regularly demeaned in the society he describes, and they have little say over their fates. Men who dominate are admired, promiscuity is taken as evidence of virility, and while virginity is venerated, the idea of removing it by force seems to be a common male fantasy. Little is fair, and outcomes seem to favour the strong and the corrupt. - Karyn Reeves

The Law is a study in the social structure of a small fishing village in Italy in the 1950's. The loosely woven story revolves around three main patriarch figures. Illicit romance, infidelity, class structure, and tradition are all subtexts of the daily life of this post-war southern Italian town. Roger Vailland captures the chaotic personal dramas unfolding against the sleepy backdrop of small town life along the Mediterranean.

Don Cesare, Matteo Brigante, and Chief of Police Attilio represent the triumvirate of power in the city of Porto Manacore. Each man carries a degree of power over the town. Don Cesare is the wealthy, elder statesman. He is a lothario with women. His harem of women rotates over the course of time as he selects particular favorites from among old Julia, Marietta, Elvira, and Maria. Matteo Brigante is the town's criminal boss; a brutal rapist and knife fighter. He is a mean man who is feared and hated by most everyone. Police Chief Attilio is married to Anna and is also a serial philanderer. He is trying to find the thief who has stolen the wallet of a tourist full of money totaling a half million lire.

Matteo Brigante's son Francesco is running away with Donna Lucrezia, the wife of Judge Alessandro. Tonio the confidence man of Don Cesare is looking for respect and to make money. His wife is Maria, formerly of Don Cesare's harem, though he is sleeping with Marietta to the dismay of her mother and sisters. They want her to be matched with an agronomist so as to profit by way of gifts and money. Marietta is the one who has stolen the money and switches wallets with Matteo Brigante so that he is arrested.

Much of the delicate personal history is revealed during a drinking game called "the Law" in which participants spill the beans about the others past indescretions or those of their wives and family. This Italian "Peyton Place" has more plots, subplots, twists and turns throughout and requires paying close attention. Oddly enough, the immorality that is the way of life in Porto Manacore seems to trouble few of the town's inhabitants. - David Fletcher

Roger Vailland was born in 1907 into a prosperous bourgeois family in Acy-Le-Multier, Oise, France. From precocious schoolboy in Reims he went on to study philosophy at the Ecole Normale and took part in the Surrealist Movement with the Grand Jeu group, at the same time as Roger Gilbert-Lecomte and René Daumal. From 1930 he worked as a journalist, covering stories throughout the world. Later he covered all the major trials for Paris-Soir, which proved an excellent preparation for his subsequent career as a novelist. During the resistance he was attached to the underground Gaullist movement and specialized in derailing trains. It was in 1944, while he was cut off from his contacts, shut up in an isolated farmhouse and armed to the teeth, that he wrote his first novel to while away the time. This was Drole de Jeu, which won the Prix Interallié in 1945. For the remainder of the war he served as a war-correspondent attached to the allied armies, and then devoted himself to writing novels and plays at his house in Ain. Work from this period, such as Les Mauvais Coups and L'Humanité placed him squarely in the ranks of the French left. Disenchantment with his lifelong attachment to the Communist party began with the collapse of the Stalin myth in 1956. The subsequent invasion of Hungary by the Russian army completed his political break with the Left. Disillusioned, he retreated to Apulia in the remote south of Italy where he came up with his masterwork, La Loi. This marked a “significant renunciation of practically everything with which the French literary consciousness had hitherto linked him.” (Keates). It also glows with his love for Apulia discovered during a series of journalistic expeditions in the 1950's. It won the Prix Goncourt.

Film review: The Law (Jules Dassin, France/Italy, 1959)

The Law, a French-Italian co-production released in Europe in 1959, might have tipped into either category. Based on a novel by Roger Vailland that won the Prix Goncourt in 1957, the film is a sweeping social allegory set in a fishing village on the coast of Puglia—a version of the primordial, elemental Italy familiar to filmgoers from Luchino Visconti’s La terra trema and Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli. The small, sun-bleached town, is equipped with a quaint central square and a population of ballad-singing layabouts (one is played by Joe Dassin, the director’s son, who would go on to a career as a major pop star in France), still under the domination of a fiercely bearded feudal lord, Don Cesare (the veteran French star Pierre Brasseur). The imperious Cesare collects heroic Greek statuary and surrounds himself with servile women, and takes it for granted that he will be able to exercise his droit du seigneur over the town’s most desirable female, the voluptuous housemaid Marietta (Gina Lollobrigida).

But Don Cesare has two younger, more up-to-date rivals for Marietta’s favors: Brigante, an aspiring gangster (Yves Montand, with a pin-striped suit and a scar on his face), and Enrico (Marcello Mastroianni), a technocrat from the North charged with cleansing the local swamps of malaria. A tragic subplot is provided by Brigante’s son, a model-pretty young man (Raf Mattioli) caught up in a passionate affair with an elegant older woman, Donna Lucrezia (Melina Mercouri), who is married to the comically impotent local judge; the chief of police, Attilio (Vittorio Caprioli), who is cheating on his matronly wife with a rail-thin younger woman, Giuseppina (Lidia Alfonsi), provides a comic variation on the theme.

This complex play of power and submission is condensed into the image of a local drinking game, called “The Law,” in which a randomly selected padrone is allowed to humiliate his companions—until the tables are turned in the next round and he becomes a victim himself.

Instead, The Law becomes a sort of Mediterranean Peyton Place, full of campy star turns, melodramatic confrontations, and relentless moralism. (“If Billy Graham were a filmmaker,” wrote Jean-Luc Godard in his withering review in Cahiers du cinéma, “he would doubtless be called Jules Dassin.”) A filmmaker who seemed capable of encapsulating entire cities a few years earlier, with the New York of The Naked City (48) and the London of Night and the City (50), suddenly cannot create a cohesive, convincing portrait of a single provincial town. Even the pigeons in the town square are charged with a heavy metaphorical burden: “Hey pigeon, why do you stay?” Joe Dassin asks a particularly oppressed-looking bird. “Because sometimes people throw them crumbs,” comes the inevitable reply.

“The result, of course, is not one good shot in two hours of film,” Godard wrote, somewhat unjustly. There is at least one good shot near the beginning: an extended crane down the front of a building, pausing at each socially encoded level to reveal the sordid goings-on within. But then Dassin cuts to Lollobrigida’s barefoot Marietta, keening seductively while polishing a man’s boot with a lusty attentiveness that a few years later would have earned an R rating. Subtlety slips away at this point, never to return.

Oscilloscope Laboratories is reissuing The Law with the French-language soundtrack that Dassin apparently considered definitive. But an English-dubbed version was released in the States by Joseph L. Levine in 1960, under a title that says it all: Where the Hot Wind Blows. - David Kehr

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.