Reza Negarestani,

Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials, re.press, 2008.

Negarestani at academia.edu

blog.urbanomic.com/cyclon/

At once a horror fiction, a work of speculative theology, an atlas of demonology, a political samizdat and a philosophic grimoire, CYCLONOPEDIA is work of theory-fiction on the Middle East, where horror is restlessly heaped upon horror. Reza Negarestani bridges the appalling vistas of contemporary world politics and the War on Terror with the archeologies of the Middle East and the natural history of the Earth itself. CYCLONOPEDIA is a middle-eastern Odyssey, populated by archeologists, jihadis, oil smugglers, Delta Force officers, heresiarchs, corpses of ancient gods and other puppets. The journey to the Underworld begins with petroleum basins and the rotting Sun, continuing along the tentacled pipelines of oil, and at last unfolding in the desert, where monotheism meets the Earth's tarry dreams of insurrection against the Sun. 'The Middle East is a sentient entity - it is alive!' concludes renegade Iranian archeologist Dr. Hamid Parsani, before disappearing under mysterious circumstances. The disordered notes he leaves behind testify to an increasingly deranged preoccupation with oil as the 'lubricant' of historical and political narratives. A young American woman arrives in Istanbul to meet a pseudonymous online acquaintance who never arrives. Discovering a strange manuscript in her hotel room, she follows up its cryptic clues only to discover more plot-holes, and begins to wonder whether her friend was a fictional quantity all along. Meanwhile, as the War on Terror escalates, the US is dragged into an asymmetrical engagement with occultures whose principles are ancient, obscure, and saturated in oil. It is as if war itself is feeding upon the warmachines, leveling cities into the desert, seducing the aggressors into the dark heart of oil ...

Cyclonopedia by Iranian mysterious philosopher Reza Negarestani is one of the best and most unusual books ever written. Part fiction part philosophy it is mostly an essay, but in such an outrageous mode that all nearby solar systems are stopping their circulations to take a look.

This is a publisher's description:

"Cyclonopedia is theoretical-fiction novel by Iranian philosopher and writer Reza Negarestani. Hailed by novelists, philosophers and cinematographers, Negarestani’s work is the first horror and science fiction book coming from and written on the Middle East.

'The Middle East is a sentient entity—it is alive!’ concludes renegade Iranian archaeologist Dr. Hamid Parsani, before disappearing under mysterious circumstances. The disordered notes he leaves behind testify to an increasingly deranged preoccupation with oil as the ‘lubricant’ of historical and political narratives.

A young American woman arrives in Istanbul to meet a pseudonymous online acquaintance who never arrives. Discovering a strange manuscript in her hotel room, she follows up its cryptic clues only to discover more plot-holes, and begins to wonder whether her friend was a fictional quantity all along.

Meanwhile, as the War on Terror escalates, the US is dragged into an asymmetrical engagement with occultures whose principles are ancient, obscure, and saturated in oil. It is as if war itself is feeding upon the warmachines, leveling cities into the desert, seducing the aggressors into the dark heart of oil ...

At once a horror fiction, a work of speculative theology, an atlas of demonology, a political samizdat and a philosophic grimoire, CYCLONOPEDIA is work of theory-fiction on the Middle East, where horror is restlessly heaped upon horror. Reza Negarestani bridges the appalling vistas of contemporary world politics and the War on Terror with the archaeologies of the Middle East and the natural history of the Earth itself. CYCLONOPEDIA is a middle-eastern Odyssey, populated by archeologists, jihadis, oil smugglers, Delta Force officers, heresiarchs, corpses of ancient gods and other puppets. The journey to the Underworld begins with petroleum basins and the rotting Sun, continuing along the tentacled pipelines of oil, and at last unfolding in the desert, where monotheism meets the Earth’s tarry dreams of insurrection against the Sun."

Here are some blurbs, but this time even blurbs are falling short:

‘Incomparable. Post-genre horror, apocalypse theology and the philosophy of oil, crossbred into a new and necessary codex.’ (China Miéville)

‘Reading Negarestani is like being converted to Islam by Salvador Dali.’ (Graham Harman)

‘It is rare when a mind has the courage to take our precious pre-conceptions of history, geography and language and turn them all upside down, into a living cauldron, where ideas and spaces become alive with fluidity and movement and breathe again with imagination and wonder. In this great novel by Reza Negarestani, we are taken on a journey that predates language and post dates history. It is all at once apocalyptic and a beautiful explosive birth of a wholly original perception and meditation on what exactly is this stuff we call “knowledge”.’ (E. Elias Merhige, director of Begotten)

‘Cyclonopedia is an extraordinary tract, an uncategorizable hybrid of philosophical fiction, heretical theology, aberrant demonology and renegade archaeology. It aligns conceptual stringency with exacting esotericism, and through its sacrilegious formulae, geopolitical epilepsy is scried as in an obsidian mirror.’ (Ray Brassier)

‘Reza Negarestani’s Cyclonopedia is rich and strange, and utterly compelling. Ranging from the chthonic mysteries of petroleum to the macabre fictions of H. P. Lovecraft, and from ancient Islamic (and pre-Islamic) wisdom to the terrifying realities of postmodern asymmetrical warfare, Negarestani excavates the hidden prehistory of global culture in the 21st century.’ (Steven Shaviro)

‘The Cyclonopedia manuscript remains one of the few books to rigorously and honestly ask what it means to open oneself to a radically non-human life – this is a text that screams, from a living assemblage known as the Middle East, “I am legion.” Cyclonopedia also constitutes part of a new generation of writing that refuses to be called either theory or fiction; a heady mixture of philosophy, the occult, and the tentacular fringes of Iranian culture – call it “occultural studies.” To find a comparable work, one would have to look back to Von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, the prose poems of Olanus Wormius, or to the recent “Neophagist” commentaries on the Book of Eribon.’ (Eugene Thacker)

‘Western readers can expect their peculiarly schizoid condition to be ‘butchered open’ by this work. Read Negarestani, and pray.’ (Nick Land)

"Partly genius, partly quite mad ... To sum up: a weirdly compelling read." (Peter Lamborn Wilson)

Last 30 pages of the book are pure philosophical LSD, mechanism of lenses for seeing the monstrous layers of our openness to butchering Outside, Aliens that are eating us. But the most surprising approach that Negarestani is deliriously describing here is that we need to be open to that massacre, to that alien culinary feast. We are here not to resist but to comply with being butchered and eaten. We have to be spiritually and physically clean so that we could be a good meal.

Here is an excerpt:

In both Drujite and Lovecraftian polytics of radical exteriority, omega-survival or strategic endurance is maintained by an excessive paranoia that cannot be distinguished from a schizophrenic delirium. For such a paranoia - saturated by parasitic survivalism and persistence in its own integrity - the course of activity coincides with that of schizo-singularities. Paranoia, in the Cthulhu Mythos and in Drujite-infested Zoroastriansim, manifests itself as a sophisticated hygiene-Complex associated with the demented Aryanistic obsession with purity and the structure of monotheism. This arch-sabotaged paranoia, in which the destination of purity overlaps with the emerging zone of the outside, is called schizotrategy. If, both for Lovecraft and the Aryans, purity must be safeguarded by an excessive paranoia, it is because only such paranoia and rigorous closure can attract the forces of the Outside and effectuate cosmic akienage in the form of radical openness - that is, being butchered and cracked open. Drujite cults fully developed this schizotrategic line through the fusion of Aryanistic purity with Zoroastrian monotheism. The Zoroastrian heresiarchs such as Akht soon discovered the immense potential of schyzotrategy for xeno-calls, subversion and sabotage. As a sorcerous line, schizotrategy opens the entire monotheistic culture to cosmodromic openness and its epidemic meshworks. As the nervous system of Lovecraftian strategic paranoia, openness is identified as 'being laid, cracked, butchered open' through a schizotrategic participation with the Outside. In terms of the xeno-call and schizitrategy, the non-localizable outside emerges as the xeno-chemical inside or the Insider.

... 'If openness, as the scimitar blade of the outside, seeks out manifestations of closure, then in the middle-eastern ethic it is imperative to assuage the external desire of the Outside by becoming what it hungers for the most' (H. Parsani)."

As you see, not an easy read, but it just means that you have to dedicate next 10 years of your life to digest it - as it eats you from within, of course. So what? Do you have any better plans? If you can imagine a hybrid of film Begotten, Deleuze's culinary writtings, Lovecraft's diary, David Lynch's letters from afterlife and Joyce's verbal acrobatics, hurry up - feed yourself with this monstrous book. It will set you sealed.

Over the last few days I've been reading Cyclonopedia. It's an incredibly strange journey through the wormholes, oil pipelines and sandstorms of the Middle East. Philosophically there's all kinds of things going on inside; Islamic and Arabic history, contemporary conflict and geopolitics, archaeology, mythology, Lovecraft, a lot of Deleuzean and - more infuriating and strange even than D&G - (pseudo?)numerology.

The central premise of the book "the Middle East is a sentient entity - it's alive!" is incredibly interesting. The ways in which oil, sand and solar economy have shaped not only Middle Eastern history and politics but global events is considered not as a function of any human sphere of interest but of an anonymous material drive goading civilisations to new creations and corruptions.

My favourite chapter of the book so far talks of Ahkt, the fallen black sun god of oil, and the Blob, the sentient drive of oil to propagate it's slimy lubricant particles. War is not the creation of war machines but vice versa and in the colonial wars of aggression of the technocapitalist nations oil is the aim, the medium and the burning remainder. Tanks fuelled by petroleum and greased by oil role across deserts and oil-based napalm clings to and disfigures landscapes.

As much fun as it is to read I just don't know what to make of the whole thing. The fictional accounts of archaeologist Hamid Parsani and American Colonel West seem redundant, since everyone seems to write in the same mode of Deleuzean auto-induced trance. Whole chapters (if not the book in its entirety) seem wilfully obscure, and I've often wondered how much attention I should pay; is this difficult paragraph an important intervention to a difficult problem, or is he making this shit up? The styling of the book as an edited series of incoherent notes is continued when you try to start researching online. This comment just about sums up the experience: "I haven’t found any other reference to this technique… Did Reza make this up?"

Presumably this blurring of the boundaries between reality, theory and fiction is precisely what Negarestani wanted. Blurring these boundaries further I had horrible nightmares last night and my girlfriend is angry at me for shouting and fighting in my sleep.

beingsufficiently.blogspot.com/search/label/Reza%20Negarestani

Notes on Negarestani’s Abducting the Outside

These are all the notes I could manage to take while still

paying sufficent attention. It should go without saying that weirdnesses

or cracks that appear are no doubt due to my memory, hand writing, or

stupidity and not to Reza!

Edit: Reza has posted his notes for the first half here.

Reza set up the talk as addressing “Genuine inhumanism” as an encounter with modern thought thereby entailing a dis-enthralled system of knowledge. He set out to do this through a series of thought pieces. These pieces began with an outline of the ambitions of post-Copernican thought to then be followed by a tripartite critique or assault against three conceptualizations of assault (and to propose a more epistemological model of acceleration as a counter). At the same time Reza noted the upswing of the various forms of acceleration he was critiquing.

In proper asymptotic fashion, Reza argued that the charge of Nick Land’s conceptualization was that the ends of reason do not lead to more reason, but simply unfold the unreasonable. Secondly, while Reza seemed to acknowledge the critical/epistemological knife of Brandom and Brassier, he set out their project as ‘axiomatic deaccelerationists’ Thirdly, Reza asked how acceleration could be understood as epistemological mediation which engenders, and is engendered by, germs of modern knowledge. Lastly, Reza proposed a diagrammatic example of modern acceleration as a form of epistemological navigation following the lead of Oresme.

Following this general map Reza began to discuss the ramifications of Modern Systems of Knowledge as he saw them. Structural, knowledge is oblique as it always works from the local to the global and functions in an asymptotic manner (ie the transcendental local can only function asymptotically). Because of this topological constraint [as opposed to something like correlationism?] knowledge can only access objects via the concept of space and therefore one must understand the topoi of thought. In the service of such topological thinking the computational relation between information and knowledge (in the form of computational or iterative myth) must be debunked). This in turn is forced by the 11th commandment – as long as there is a possible path, it is mandatory to take it. Modern knowledge is a thrall to space.

This enthrallment worms its way into the question ‘what is the concept?’ The question becomes how is the concept an information space that can be integrated into the apparently non-informational [the physical, structural, etc?] Here Reza entered into a discussion of Longo’s gestural thinking. [As I am just getting into Longo I cant really do this justice] Gestural thinking works in detecting symmetries as concepts are produced by normativity as geometrical gestures. Because of the importance of the topological for the conceptual, mathematics become the science of the concept since math transfers the invariances as the gesture that has maximal gestural stability.

[To go into the math of the gesture Reza produced two diagrams connecting the relation of information and form, leaping from Aristotelian formulations, in order to illustrate how the question of 'what is the concept?' is overridden by the question 'where is the concept?' leading to a deep ecology of the concept.]

The space of the concept can be thought of in terms of the shell that the snail carries on its own back ie concepts are no longer discrete but are mobile (concepts are the topos of the concept). How does one then locate the concept if it is constantly shifting like a metamorphic protean god? Computational dynamics sees this as the problem as repeated localization whereas it is actually ramifications of the locality of the concept that pushes it into the open.

Here Reza mentioned the Bourne Identity as linking together the where I am with the who I’m I [brings up a tactical vision of the snail] Each question is a new plot line moving through ramified concepts. This engenders a anti-Heideggerian move, roots are always mobile. Following such a model of navigation the transcendental procedure is taken to the extreme as asymptotic due to the structure of the object and the structure becomes restructured asymptotically through the operations of the concept.

Reza then reiterated the agenda of his tripartite critique in which all the targets are guilty of deep access whether machinic (Land), normative (Brassier), political (Marxism).

Land’s accelerationism functions programatically and not epistemologically working towards the Machinic Singularity via the computational regime. Computational dynamics hinge on algorithmic processes whose iterative nature explains its efficacy. Iteration only functions in finite time and hence the speed of acceleration. Against this Reza discussed Poincare’s critique of the contingency of the iterative loop apparent in high frequency trade and the failure of battlespace virtualization. The iterative medium cannot handle contingency but only the pseudo-randomness of Laplace and Hilbert. This pseudo-randomness is bound to Frege’s absolute logocentric formalism and the confines of Hilbert space. Hilbert believed that the world could be broken down into data-cubes. For Hilbert small perturbations were unimportant and interations lead to an increase in precision and therefore the consequences of iteration are meta-predictable. Such thinking should be combated as participating in the metaphysics of necessity. One should utilize infinite contingency against predictability. Turing and Hilbert see the algorithmic process as deterritorializing the entire planet. Small perturbations are infinite and finite and have real consequences down the line.

One should strive for coherency over consistency (which is too normative in the end). The physical world is one of geodesic principles and the straightforward use of information is lost as one must take into account entanglement. Furthermore, the machine algorithm has no place for ignorance. Laws are not a priori given in physical space – they are the result of the observer working within geodesic space. The rational unfolds the unreasonable. Algorithmic thought on the other hand can only answer ‘yes or no’ as its ‘ignorance’ is already axiomatically decided. Algorithmic thinking thereby collapse falsifiability and ignorance. The machinic becomes purely strategic and ideological.

Reza then turned to Brassier and Brandom. The normative turn of certain Sellarsians suffers from an inference problem since norms are by definition recursive and therefore always yield the same result. In this sense normativity is a mode of iteration. Against normativity acceleration should be followed as the catastrophic rearrangement of the limits of the system. Peirce pushes normative though a synthesis of thinking and doing and not a metaphysical enactivism but a form of gesture as a form of action (in the same way as Bertholz). These gestures stem from viewing reason (via Chatelet) as a ration of thought to nature. Reason is the broadening of the scope of oscillation between nature and culture in a rational to and fro-ing. Broader forms of reasoning are required. Abductive reasoning or manipulative epistemology are good mental labs for developing extreme hypotheses. We should embrace violent noetic propulsions which are mutilating as non-neutral observers are imported into fuzzy zones.

Observers are forced to work in a disequilibrial dynamics or twisted contingency but a rational disequilibrium introducing new forms into space. Acceleration responds to the global scope of knowledge – concepts need to be released out into the open (the catastrophes and disasters of Rene Thom) demanding the subject to improvise into contingency. Acceleration functions as the epistemic navigation of the concept space introducing dialectical instability.

Chatelet’s dialectics are a form of alien communication, they are a form of imperfect cutting or dialectical severance as an insider is left in what is cut off leading to a new ratio or intermix of thought and nature. The accelerationist gesture creates cognitive attractors which attracts ignorance as mitigation. Acceleration functions as a means of thinking catastrophes in order to establish a new accessibility. Truth is co-constituitve with error, truth is non-conceptual whereas for Brassier action produces pragmatics with a prestablished relation to nature. An alternative model is that of the long forgotten practice of metis or cunning reason against the regime of simulation as seen in the work of Benedict Singleton. Another promising avenue is the anarchic constructivism of Gabriel Catren in which the thinker or navigator is the gluing together of the rebel and the foundationalist. We should pursue metisocratic reason towards the unreasonable and engage in an ethics of humiliation.

speculativeheresy.wordpress.com/tag/reza-negarestani/Reza set up the talk as addressing “Genuine inhumanism” as an encounter with modern thought thereby entailing a dis-enthralled system of knowledge. He set out to do this through a series of thought pieces. These pieces began with an outline of the ambitions of post-Copernican thought to then be followed by a tripartite critique or assault against three conceptualizations of assault (and to propose a more epistemological model of acceleration as a counter). At the same time Reza noted the upswing of the various forms of acceleration he was critiquing.

In proper asymptotic fashion, Reza argued that the charge of Nick Land’s conceptualization was that the ends of reason do not lead to more reason, but simply unfold the unreasonable. Secondly, while Reza seemed to acknowledge the critical/epistemological knife of Brandom and Brassier, he set out their project as ‘axiomatic deaccelerationists’ Thirdly, Reza asked how acceleration could be understood as epistemological mediation which engenders, and is engendered by, germs of modern knowledge. Lastly, Reza proposed a diagrammatic example of modern acceleration as a form of epistemological navigation following the lead of Oresme.

Following this general map Reza began to discuss the ramifications of Modern Systems of Knowledge as he saw them. Structural, knowledge is oblique as it always works from the local to the global and functions in an asymptotic manner (ie the transcendental local can only function asymptotically). Because of this topological constraint [as opposed to something like correlationism?] knowledge can only access objects via the concept of space and therefore one must understand the topoi of thought. In the service of such topological thinking the computational relation between information and knowledge (in the form of computational or iterative myth) must be debunked). This in turn is forced by the 11th commandment – as long as there is a possible path, it is mandatory to take it. Modern knowledge is a thrall to space.

This enthrallment worms its way into the question ‘what is the concept?’ The question becomes how is the concept an information space that can be integrated into the apparently non-informational [the physical, structural, etc?] Here Reza entered into a discussion of Longo’s gestural thinking. [As I am just getting into Longo I cant really do this justice] Gestural thinking works in detecting symmetries as concepts are produced by normativity as geometrical gestures. Because of the importance of the topological for the conceptual, mathematics become the science of the concept since math transfers the invariances as the gesture that has maximal gestural stability.

[To go into the math of the gesture Reza produced two diagrams connecting the relation of information and form, leaping from Aristotelian formulations, in order to illustrate how the question of 'what is the concept?' is overridden by the question 'where is the concept?' leading to a deep ecology of the concept.]

The space of the concept can be thought of in terms of the shell that the snail carries on its own back ie concepts are no longer discrete but are mobile (concepts are the topos of the concept). How does one then locate the concept if it is constantly shifting like a metamorphic protean god? Computational dynamics sees this as the problem as repeated localization whereas it is actually ramifications of the locality of the concept that pushes it into the open.

Here Reza mentioned the Bourne Identity as linking together the where I am with the who I’m I [brings up a tactical vision of the snail] Each question is a new plot line moving through ramified concepts. This engenders a anti-Heideggerian move, roots are always mobile. Following such a model of navigation the transcendental procedure is taken to the extreme as asymptotic due to the structure of the object and the structure becomes restructured asymptotically through the operations of the concept.

Reza then reiterated the agenda of his tripartite critique in which all the targets are guilty of deep access whether machinic (Land), normative (Brassier), political (Marxism).

Land’s accelerationism functions programatically and not epistemologically working towards the Machinic Singularity via the computational regime. Computational dynamics hinge on algorithmic processes whose iterative nature explains its efficacy. Iteration only functions in finite time and hence the speed of acceleration. Against this Reza discussed Poincare’s critique of the contingency of the iterative loop apparent in high frequency trade and the failure of battlespace virtualization. The iterative medium cannot handle contingency but only the pseudo-randomness of Laplace and Hilbert. This pseudo-randomness is bound to Frege’s absolute logocentric formalism and the confines of Hilbert space. Hilbert believed that the world could be broken down into data-cubes. For Hilbert small perturbations were unimportant and interations lead to an increase in precision and therefore the consequences of iteration are meta-predictable. Such thinking should be combated as participating in the metaphysics of necessity. One should utilize infinite contingency against predictability. Turing and Hilbert see the algorithmic process as deterritorializing the entire planet. Small perturbations are infinite and finite and have real consequences down the line.

One should strive for coherency over consistency (which is too normative in the end). The physical world is one of geodesic principles and the straightforward use of information is lost as one must take into account entanglement. Furthermore, the machine algorithm has no place for ignorance. Laws are not a priori given in physical space – they are the result of the observer working within geodesic space. The rational unfolds the unreasonable. Algorithmic thought on the other hand can only answer ‘yes or no’ as its ‘ignorance’ is already axiomatically decided. Algorithmic thinking thereby collapse falsifiability and ignorance. The machinic becomes purely strategic and ideological.

Reza then turned to Brassier and Brandom. The normative turn of certain Sellarsians suffers from an inference problem since norms are by definition recursive and therefore always yield the same result. In this sense normativity is a mode of iteration. Against normativity acceleration should be followed as the catastrophic rearrangement of the limits of the system. Peirce pushes normative though a synthesis of thinking and doing and not a metaphysical enactivism but a form of gesture as a form of action (in the same way as Bertholz). These gestures stem from viewing reason (via Chatelet) as a ration of thought to nature. Reason is the broadening of the scope of oscillation between nature and culture in a rational to and fro-ing. Broader forms of reasoning are required. Abductive reasoning or manipulative epistemology are good mental labs for developing extreme hypotheses. We should embrace violent noetic propulsions which are mutilating as non-neutral observers are imported into fuzzy zones.

Observers are forced to work in a disequilibrial dynamics or twisted contingency but a rational disequilibrium introducing new forms into space. Acceleration responds to the global scope of knowledge – concepts need to be released out into the open (the catastrophes and disasters of Rene Thom) demanding the subject to improvise into contingency. Acceleration functions as the epistemic navigation of the concept space introducing dialectical instability.

Chatelet’s dialectics are a form of alien communication, they are a form of imperfect cutting or dialectical severance as an insider is left in what is cut off leading to a new ratio or intermix of thought and nature. The accelerationist gesture creates cognitive attractors which attracts ignorance as mitigation. Acceleration functions as a means of thinking catastrophes in order to establish a new accessibility. Truth is co-constituitve with error, truth is non-conceptual whereas for Brassier action produces pragmatics with a prestablished relation to nature. An alternative model is that of the long forgotten practice of metis or cunning reason against the regime of simulation as seen in the work of Benedict Singleton. Another promising avenue is the anarchic constructivism of Gabriel Catren in which the thinker or navigator is the gluing together of the rebel and the foundationalist. We should pursue metisocratic reason towards the unreasonable and engage in an ethics of humiliation.

Cyclonopedia is one of those books that drives you ecstatic for being so different from anything you have ever read so far. In this book, Iranian Philosopher Reza Negarestani elaborates a beautiful narrative of the Middle East seen as a sentient and alive entity. Following the tracks of Deleuze & Guatarri’s Thousand Plateaus, Negarestani go far beyond them by granting an alive autonomy to every entities composing the Middle East (sand, dust, oil, plague, rust, war, bullets, rats, corpes, Zoroastrian divinities etc.) except maybe human being themselves.

The text is very obscure and sometimes even esoteric, but the feeling of being lost in it provides even more jubilation when a paragraph becomes vivid for the reader.

Here are some beautiful excerpts (and there are so much more in the book):

“Everywhere a hole moves, a surface is invented. When the despotic necrocratic regime of periphery-core, for which everything should be concluded and grounded by the gravity of the core, is deteriorated.” P50

“Rats are exhuming machines. Not only full fledged vectors of epidemic, but also ferociously dynamic lives of ungrounding. […]

A surface-consuming plague is a pack of rats whose tails are the most dangerous seismic equipment; tails are spatial synthesizers (fiber-machines), exposing the terrain which they traverse to sudden and violent folding and unfolding, while seizing patches of ground and composing them as a non human music. Tails are musical instruments, playing metal -tails, lasher tanks in motion. Although tails have a significant locomotive role, they also act as boosters of agility or anchors of infection.” P52

“A self-degenerating entity, a volunteer for its own damnation, dust opens new modes of dispersion and of becoming-contagious, inventing escape routes as yet unrecorded. In his interview, Parsani suggests that the Middle East has simulated the mechanisms of dusting to mesh together an economy which operates through positive degenerating processes, an economy whose carriers must be extremely nomadic, yet must also bear an ambivalent tendency towards the established system or the ground. An economy whose vehicle and systems never cease to degenerate themselves. For in this way, they ensure their permanent molecular dynamism, their contagious distribution and diffusion over their entire economy.” P91

“If, in middle-eastern tradition, gods deliberately allow themselves to be killed left and right by enemies, humans, or themselves without any prudence as to their future and eventual extinction, it is because they find more significance and benefit in their own corpes –as a concrete object of communication and tangibility among humans- than in the abstractness of their divinity. At last, as corpes, they can copulate and contaminate.” P205

Leper Creativity: Cyclonopedia Symposium, punctum books, 2012.

cyclonopediasymposium.blogspot.hr/

on vimeo

Essays, articles, artworks, and documents taken from and inspired by the symposium on Reza Negarestani’s Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials, which took place on 11 March 2011 at The New School. Hailed by novelists, philosophers, artists, cinematographers, and designers, Cyclonopedia is a key work in the emerging domains of speculative realism and theory-fiction. The text has attracted a wide-ranging and interdisciplinary audience, provoking vital debate around the relationship between philosophy, geopolitics, geophysics, and art. At once a work of speculative theology, a political samizdat, and a philosophic grimoire, Cyclonopedia is a Deleuzo-Lovecraftian middle-eastern Odyssey populated by archeologists, jihadis, oil smugglers, Delta Force officers, heresiarchs, and the corpses of ancient gods. Playing out the book’s own theory of creativity – “a confusion in which no straight line can be traced or drawn between creator and created – original inauthenticity” (191) – this multidimensional collection both faithfully interprets the text and realizes it as a loving, perforated host of fresh heresies. The volume includes an incisive contribution from the author explicating a key figure of the novel: the cyclone. CONTENTS: Robin Mackay, “A Brief History of Geotrauma” – McKenzie Wark, “An Inhuman Fiction of Forces” – Benjamin H. Bratton, “Root the Earth: On Peak Oil Apophenia” – Alisa Andrasek, “Dustism” – Zach Blas, “Queerness, Openness” – Melanie Doherty, “Non-Oedipal Networks and the Inorganic Unconscious” – Anthony Sciscione, “Symptomatic Horror: Lovecraft’s ‘The Colour Out of Space’” – Kate Marshall, “Cyclonopedia as Novel (a meditation on complicity as inauthenticity)” – Alexander R. Galloway, “What is a Hermeneutic Light?” – Eugene Thacker, “Black Infinity; or, Oil Discovers Humans” – Nicola Masciandaro, “Gourmandized in the Abattoir of Openness” – Dan Mellamphy & Nandita Biswas Mellamphy, “Phileas Fogg, or the Cyclonic Passepartout: On the Alchemical Elements of War” – Ben Woodard, “The Untimely (and Unshapely) Decomposition of Onto-Epistemological Solidity: Negarestani’s Cyclonopedia as Metaphysics” – Ed Keller, “. . .Or, Speaking with the Alien, a Refrain. . .” – Lionel Maunz, “Receipt of Malice” – Öykü Tekten, “Symposium Photographs” – Reza Negarestani, “Notes on the Figure of the Cyclone” punctumbooks.com

Who invited these people? Classically (and etymologically, too), a symposium involves drinking and good conversation. The model is Plato’s celebrated dialogue, in which the topic of love is on the table. Socrates’s sobriety tempers the mood somewhat, but Aristophanes’s riotous fantasy of primordial togetherness—conjoined human halves doing cartwheels across a mythical landscape—assures that good cheer predominates. Not so here. Ed Keller, Nicola Masciandaro, and Eugene Thacker have thrown a hellish get-together where gooey matter makes it all but impossible for Platonic forms to appear. Reza Negarestani’s pitch-black meditations on oil and the sublunary contingencies it incarnates provide the stuff of discourse and thought.

For the cyclonopediasts, the end of the world has already begun. Since the path between origin and extinction is not a straight line, Leper Creativity charts the irregular but certain course toward annihilation on various terrains. The proceedings do not unfold against a backdrop of what the Middle Ages, still preserving ancient philosophers’ faith in the world and its ways, called natura naturans. Rather, the whole universe seems to have collapsed upon itself. The primeval root of all things lies in the hostile matter that once was sun and light, but now lies thick and congealed in the stagnant, barren earth. Oil is fuel, but not sustenance—the organic turned enemy of life.

Accordingly, the matter of love is a sticky mess. Like so many transsexual Transylvanians, one pictures the symposiasts arriving on iron steeds that belch forth smoke and fire before dancing a theoretical “Time Warp.” The spectacle can be considered inviting and repellent in equal measure. Contributor Zach Blas offers an assessment of “queer openness” that, in his view, often seems as turgid and dull as the beefcake bonehead Rocky Horror. His salutary advice to celebrants of the rainbow is to embrace decay. The rectum is indeed a grave (Leo Bersani), and its heady perfume the immanent hereafter—the “no future” of the surprisingly alive death drive (Lee Edelman). Melanie Doherty, taking up Deleuze and Guattari, sharpens her teeth on the Oedipal fantasies that sustain the likes of Brad, Janet, and other squares enamored of triangular family romances. Discussing cosmic horror fiction, she remarks the corrosive power of the “radical outsider,” who “never appears as a discrete entity or individuated substance beyond vague indications of motion and fog.” It’s a monster, not a choice, and the choice is not ours to make. Love and other “symptoms of transmutation and madness” undo more than a happy couple can bring together.

To get the most from this gathering, the gentle reader is advised not to plunge headlong into the murk, but, like another amphibian dwelling between elements, to move back and forth between spots of (relative) stability and the puddles that bubble up from the deep around which the symposiasts assemble. In so doing, she or he can, without getting too messy, explore Robin Mackay’s reflections on geotrauma, Alisa Andrasek’s discussions of dust and detritus, and Ben Woodard’s investigation of how “onto-epistemological solidity” falls prey to decomposition. Occasionally, as in Kate Marshall’s contribution (“Cyclonopedia as Novel [A Meditation on Complicity as Inauthenticity]”), the question arises as to what exactly it means to immerse oneself in this “world without end.” Negarestani himself offers “Notes on the Figure of the Cyclone” in guise of a conclusion: the “meaninglessness of the free sign,” shooting across the horizon like a comet, is as close as we come to a final word.

One more example will indicate what lurks within the pages of Leper Creativity. “Gourmandized in the Abattoir of Openness” by editor and instigator Masciandaro pairs quotes from the “black metal” musician Xasthur and German mystic Meister Eckhart. The modern and the medieval voices are united by the view that death inhabits life. The “dark night of the soul,” as St. John of the Cross (1542–1591) put it, is the site where human existence, by embracing its nullity, discerns the prospect, however remote, of redemption and something more than what it is—and is not. The baroque-and-Barolo sensibility that Masciandaro and his fellow hosts exhibit is not unwelcoming, but it does involve acquired tastes. Edgar Allan Poe and H. P. Lovecraft are the evening’s sommeliers. As one might predict, canonical party animals like James Joyce, William S. Burroughs, and Kathy Acker feature prominently. But if they occasionally hog the bottle, the spirits keep flowing up from the cellar. It’s not difficult to see in the interstices of the text the presence of other writers whose profiles are generally less familiar. In particular, Otto Weininger, Victor Tausk, and Wilhelm Reich—rogue apprentices of psychoanalytic alchemy—seem to have contributed their theoretical concoctions to the off-kilter mood.

History, Karl Marx famously observed, first occurs as tragedy, then as farce. But what if—as is supposedly the case in a “postmodern” world—history never existed in the first place? What if the events that happen in the universe are simply spectacles to be viewed with earnest terror and pity or, alternately, with bemusement bordering on sinister delight? The latter, it seems, is the perspective adopted by most contributors to Leper Creativity, whose idea of a symposium owes more to Petronius, the first-century satirist of imperial Rome, than it does to philosophical idealism, ancient or modern. Another possibility is that the convivial bunch is raising its glasses to Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose unfinished novel Petrolio nods in a twentieth-century context to the decadence indicted and celebrated by Petronius; petroleum, after all, is the substance that Negarestani and his disciples pour at this version of the Last Supper.

No low-octane drinks are on offer at Leper Creativity, and the crowd can be rowdy. But it’s a party, not a program. A sense of moderation will assure you a little unwholesome fun during the end times that started millennia ago. Whatever it is, it’s (always already) happening, so you might as well try to figure it out for yourself. Plus, in the digital domain, the experience doesn’t cost anything. The universal truth of the apocalypse is that everyone—whether afflicted, anointed, or both—rides for free. Get with it, or get left behind. - Erik Butler

Another symposium collection, Leper Creativity: Cyclonopedia Symposium (punctum books, 2011) brings together scholars to discuss Reza Negarestani’s world-warping book Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials (re.press, 2008). Not since Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (Pantheon, 2000) have I been so simultaneously intrigued and scared of a book. It is a return to the “hidden prehistory” (as Steven Shaviro describes it) of the dark global forces of the twenty-first century. It is at once philosophical fiction, nomad archeology, Middle Eastern occult study, object-oriented ontology, and straight-up horror, all centered on Western civilization’s lust for oil, the darkest of matters. Leper Creativity sets out to excavate this work’s dark secrets. Their own introductory language reads as follows:

Essays, articles, artworks, and documents taken from and inspired by the symposium on Reza Negarestani’s Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials, which took place on 11 March 2011 at The New School. Hailed by novelists, philosophers, artists, cinematographers, and designers, Cyclonopedia is a key work in the emerging domains of speculative realism and theory-fiction. The text has attracted a wide-ranging and interdisciplinary audience, provoking vital debate around the relationship between philosophy, geopolitics, geophysics, and art. At once a work of speculative theology, a political samizdat, and a philosophic grimoire, Cyclonopedia is a Deleuzo-Lovecraftian middle-eastern Odyssey populated by archeologists, jihadis, oil smugglers, Delta Force officers, heresiarchs, and the corpses of ancient gods. Playing out the book’s own theory of creativity – “a confusion in which no straight line can be traced or drawn between creator and created – original inauthenticity” – this multidimensional collection both faithfully interprets the text and realizes it as a loving, perforated host of fresh heresies. The volume includes an incisive contribution from the author explicating a key figure of the novel: the cyclone.More than worthy of a symposium as such, Cyclonopedia bridges and problematizes the divide between modern, global politics and the dark forces of ancient humanity. Claudia Card (2002) wrote, “The denial of evil has become an important strand of twentieth-century secular Western culture” (p. 28). To deny evil is to deny ourselves, to deny a part of our positive nature. Cyclonopedia digs deep into both sides. It is a triumph in both form and content. We’re dropped into the first hole in the plot as a young American woman arrives at a hotel in Istanbul to meet an online acquaintance with an unpronounceable name who never actually shows up. She finds a manuscript in her hotel room and begins culling its clues leaving her to wonder if her friend from afar was real at all (as Johnny did Zumpano in House of Leaves). “Meanwhile, as the War on Terror escalates,” the jacket copy explains, “the U. S. is dragged into an asymmetrical engagement with occultures whose principles are ancient, obscure, and saturated in oil. It is as if war itself is feeding upon the warmachines, leveling cities into the desert, seducing the aggressors into the dark heart of oil.” As Howard Bloom (1995) explains, “Behind the writhing of evil is a competition between organizational devices, each trying to harness the universe to its own particular pattern, each attempting to hoist the cosmos one step higher on a ladder of increasing complexity” (p. 325). The Middle East is sentient, alive, proclaims the embedded manuscript’s author Dr. Hamid Parsani, dark forces its lifeblood, its story the evil of all of history — human and nonhuman.

“Evil is a by-product, a component, of creation” Bloom (1995, p. 2) writes matter-of-factly. To understand its legion forces, we have to look extensively at the edges between nefarious, non-human history, as well as the insidious inside ourselves. It is in this way that the draw of Black Metal and the study of its ethos is something we cannot afford to ignore. - Roy Christopher

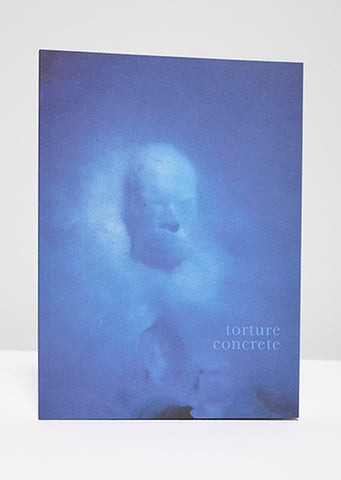

Reza Negarestani, Torture Concrete: Jean-Luc Moulène and the Protocol of Abstraction, Sequence Press, 2014.

Reza Negarestani’s essay is published in conjunction with Jean-Luc Moulène’s exhibition, Torture Concrete, September 7 – October 26, 2014 at Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York. The text emerged out of a number of conversations between the writer and artist around the theme of abstraction both as a multi-faceted project in the general domain of thought and as a specific process of artistic experimentation. Negarestani sharply asserts abstraction’s origins as the dialectic between form (mathematics) and sensible matter (physics) and its otherwise flat interpretation in art history, and presents us with the redemptive possibilities for its enrichment and diversification through the lens of artistic practice.

Negarestani calls into question the “self-reflexive history of art” as having embezzled this singular definition of abstraction, so that one can no longer link it to its constitutive gesture or procedural coherence, and locates Moulène’s work safely at the outer-edges of this “impoverished” history. He asserts that for Moulène, “the task of art is rediscovered not in its ostensible autonomy but in its singular power to rearrange and destabilize the configurational relations between parameters of thought, parameters of imagination and material constraints which parameterize the cognitive edifice.”

Moulène seeks to define new objectives for art and to further revise its task using his own working paradigm of topology and dynamic systems. Within the artist's work—the work of systematization of experimentation and producing tools for thinking—Negarestani finds a reassuring pursuit in practice, that of the unearthing of a buried dialectic, and a worthy response to his problematic: “We’ve all heard of abstraction, but no one has ever seen one.”

Both men work in search of a means of emancipation from a tortured position (as writer, artist, human). For Moulène, making a change to the body, a change from within, works alongside the notion of thought making a difference in the world. But in order for thought to do this, as Negarestani suggests, “first it must make a difference in itself—this is where abstraction finds its true vocation.”

A Review of Jean-Luc Moulène's Torture Concrete by Brendan C. Byrn PDF

Reza Negarestani: The Labor of the Inhuman, Part I: Human

The Labor of the Inhuman, Part II: The Inhuman

The Dust Enforcer: "To live in dust requires a certain degree of demonism..."

Reza Negarestani is an Iranian writer and philosopher who has worked in different areas of contemporary philosophy, speculative thought, and politics. These studies inform his stories, which tend to use the shell of nonfiction forms in a Borgesian way, often as a delivery system for the weird. His most recent book is Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials […]

All of a Twist: An Exploration of Narration, Touching on Negarestani's Novel Cyclonopedia

Reza Negarestani is the author of Cyclonopedia, perhaps our favorite weird book of the twenty-first century. – The Editors In order to think narration in a world that is devoid of any narrative necessity – an expanding space into which all ideas of embodiments dissolve and an absolute time whose radical contingency aborts any necessary difference to which a narrative can […]

The Gallows-Horse: "In its larval stage of development, it began to fully appear as a...linguistic crypto-object."

With the publication of Cyclonopedia, Reza Negarestani catapulted to the forefront of the most interesting uncanny writers of the twenty-first century. Given that his work partakes heavily of nonfiction forms and of philosophical approaches to The Weird, even though also quite visceral, Negarestani may not be to everyone’s taste. But he is clearly the most […]