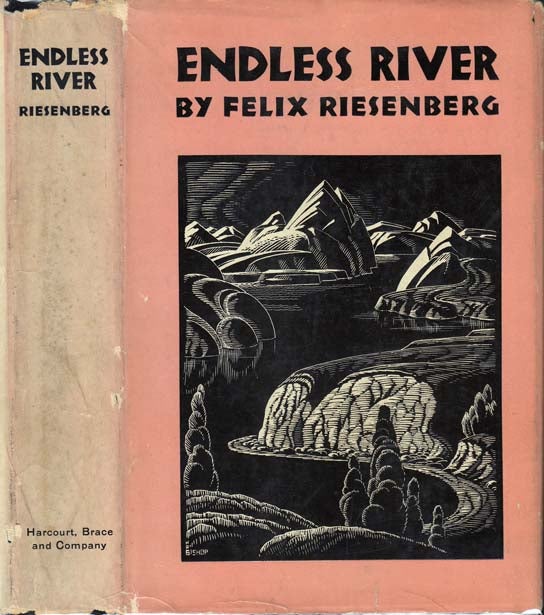

Felix Riesenberg, Endless River, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1931.

Continuing my way through the works of Felix Riesenberg, the long-forgotten American merchant mariner-engineer-writer, I took up his most experimental work,

Endless River

(1931). I’ve yet to make up my mind whether Riesenberg was a great or merely a good writer, but he was, unquestionably, a remarkable one, and there is no better proof of that than this striking book.

On the epigraph page, Riesenberg quotes the critic

Harry Hansen: “There is only one definition for a novel–it is the way the man who writes it looks at the world. And there are as many ways of writing a novel as there are ways of looking at the world.” As one reviewer, Robert Leavitt, wrote in

The Saturday Review, “Accept Mr. Hansen, and

Endless River

is a novel. Reject him, and it is a formless

pot pourri.

Well, even as a novel, it’s a formless

pot pourri. Or rather, it has no more form than a river, which is why one of the very few critics to even notice the book compared it, not surprisingly, to

Finnegans Wake

. “Books–novels, treatises, tracts, and the like–are chopped into chapters. But you cannot cup up a river. You cannot stop it and let a little trickle out after filering impurities. The river keeps on, and so does this, until lost in the endless paths of time.”

Unlike

Finnegans Wake

, though, Riesenberg’s river is not one continuing stream of words but three-hundred-some pages of fragments. Some are little essays. Some are segments of short stories or character sketches that span a few pages. Many are, I assume, Riesenberg’s own musings. One after another they flow through the pages until the end is reached.

Unlike a real river, however, which at least has gravity as an identifiable driving force,

Endless River

appears to have no purpose behind it other than to satisfy Riesenberg’s fascination with the swirling currents of humanity he observes in the streets of Manhattan. In which case, a better parallel to

Endless River

than would be Dos Passos’

Manhattan Transfer

, which is less a novel than a collage of narratives, popular songs, advertisements, and set pieces.

In Dos Passos’ case, however, as with his trilogy

U.S.A.

, the stories are threads that run throughout the book, while Riesenberg’s characters are more like landmarks his river touches and then leaves behind for good.

There are some wonderful sketches in the book, such as the wealthy dandy who finds himself stranded in upper Manhattan late one night and finds himself slowly losing his identity on his long walk home. Or Major John Hollister Truetello, who writes out the same four letters every night (“My dear sir, may I not adress you so, you the happy father of a newborn babe…”) and sends them off to four addressees picked out from various directories. Or Old Mr. Kindleberry, who carefully records names in his notebook.

Each day he chose a letter, and for twenty lines, after the greatest care and consideration, he wrote euphonious words, one under the other, spelling them out with rare and discriminating joy. Mr. Kindleberry never made a mistake in spelling; it was a little joke of his own, for the words he wrote down were of his own invention…. Here are some of his words, beginning with the letter D: Dianop; Dathter; Dilldyle; Daggerhampton; Dopda.

While there is a little something Borgesian about Truetello, Kindleberry, and a few of the three or four dozen characters in the book, they are all more symbols than convincing personalities.

“Which character in

Endless River

are you?” reads the marker ribbon in the first–and so far, only–edition. “None,” I suspect most readers would answer. Riesenberg’s characters are, in fact, just bits of flotsam and jetsam caught up in this outpouring of words. They are there to serve his purpose, which seems mostly to be to argue that there is no point in trying to give any form to the lives and interactions of men. At least for some time to come. “If we are right today (I mean 1931 or thereabout), then in 256,789 we should be stabilized.”

Until then, Riesenberg seems to argue, billions more bits of humanity will be carried along in the endless river. “There was never a writer less literary in temperament than Felix,” wrote his friend Christopher Morley in a

Saturday Review piece after his death in 1939. “His sheer lack of conscious technique makes him irresistible. Put him under a sudden gust of emotion and watch his penmanship.”

“Penmanship” is hardly a word that a writer would want his work described as, but I have to wonder if

Endless River

would have gained a publisher in the first place without the influence of friends like Morley. However, whether it ultimately comes to be judged a novel, a

pot pourri, or just a unique flood of prose, it is certainly a testament of a writer with a powerful need to tell how he looked at the world. -

https://neglectedbooks.com/?p=1717

Felix Riesenberg, P. A. L.: A Novel of the American Scene,

Felix Riesenberg, P. A. L.: A Novel of the American Scene, Robert M. McBride & Co., 1925

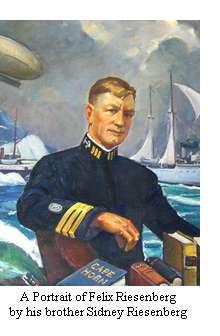

Felix Riesenberg (1879-1939) worked in the Merchant Marine, was part of two unsuccessful attempts to reach the North Pole by airship, served as a civil engineer for the state of New York, ran the

New York Nautical School (now the State University of New York Maritime College), and was Chief Officer of the

U. S. Shipping Board. He also wrote several books about the sea, including the manual,

Standard Seamanship for the Merchant Service (1922).

And then, around the age of 44, he decided to write a novel.

P.A.L.

–the resulting book–does start at sea, with the dramatic wreck of a beat-up Russian freighter carrying refugees in a storm off the coast of Washington State. The writing certainly demonstrates Riesenberg’s familiarity with the ways of ships and the sea.

By page 10, however, the sea is left behind, never to be revisited. Lieutenant Dimitri Marakoff, master of the ship at the time of its sinking, is washed ashore with other survivors, and, taken for an Englishman, listed as D. Markham. Given a new set of clothes, a few dollars, and a referral to a businessman named P. A. L. Tangerman, D. Markham is sent off to Seattle to make his way.

In Seattle, he learns that Tangerman is the entrepeneur responsible for introducing the Cudahy Vacuum Dome. Not knowing whether that’s “a mountain or a mine,” he goes to see Tangerman. A brash, cigar-puffing man clearly assured of his own ingenuity, Tangerman accepts Markham as an Englishman without a second thought, and takes an immediate liking to Markham. He offers him a job as some kind of private advisor and sends him out the door with referrals to a haberdasher and a boarding house.

Only then does Markham see the dome, being demonstrated in a downtown storefront: “an immense bulb of bright aluminum” with “the outlines of an exaggerated coal-scuttle helmet.” Copper pipes connect it to a vacuum motor: “The great invention was intended to cause hair to sprout on bald heads, by relieving the air pressure above the cranium.” In other words, an elaborate gimmick for curing baldness.

No one, however, doubts the genius of Tangerman or the certain success of the dome. And Tangerman has other enterprises: Vim Vigor V. V., a vitamin tonic; Glandula, a miracle elixir made from sheep glands; four different brands of cigars and cigarettes, all made from the same tobacco. Hailed as a titan of American industry, Tangerman works into the wee hours jotting down the secrets to success.

It’s all heady, exciting stuff for Markham and the many others in his orbit. Only no one ever sees much in the way of cash. And when the dome is accused of blowing up and injuring a customer, everyone from the haberdashers to the office furniture store start taking back their goods.

This proves a temporary set-back, though, and soon Tangerman and Markham are off to Chicago to make an even bigger splash. Tangerman founds a correspondence course school, a publishing house for cheap editions of the classics, and several magazines. One of them,

Marcus and Aurelius, aims at being the most outrageous bundle of claims around–a precursor of the

Weekly World News. It celebrates all of Tangerman’s gimmicks and more:

[F]ly traps, stills, liquor flavors, beer powders, trick sets, face lifting, jumping dice, depilatories, deodorizers, whirling sprays, installment diamonds, eye brighteners, nose straighteners, stammering cures, permanent curls, lip sticks, blush controllers, dimple makers, gallstone removers, self-bobbers, liquor agers, tape worm expellers, rubber underwear, hair restorers, finger print messages, sleuthing secrets, pyorrhoea, lucky rings, hypnotism, halitosis, pimple cures, lover’s secrets, pile removers, racing tips, dancing steps, etiquette, and short story courses.

“Print dirt, but don’t dose it with perfume,” is the editor’s maxim.

Tangerman buys land along Lake Michigan, builds an enormous mansion with its own power plant, buys a great yacht on which he throws wild parties with plenty of bootleg booze. He keeps surfing from one wave of speculation to another, all of based on little or no hard capital. And though he marries a sweet girl from Seattle for who Markham carries a torch, he keeps up a steady stream of mistresses, including the psychic, Countess Voluspa Balt-Zimmern.

Tangerman’s ventures also keep spiralling up from the ridiculous to the insane, culminating in a secret pact with a lunatic miner with a box full of gold in fine sand form. The miner claims to have found a huge deposit of the stuff off in some unnamed desert in the West, and Tangerman and all his fellow speculators become drunk on the possibilities of the world’s greatest gold find.

As one might expect, the bubble eventually pops, and with devastating–and in Tangerman’s case, fatal–results.

P.A.L. is reminiscent of two novels from twenty years earlier: Frank Norris’

The Octopus and

The Pit, both of which attacked the blind destructiveness of speculation. But it’s also very much a novel of the 1920s and wild stock speculation, which ultimately led to the great market crash of 1929. Riesenberg’s work has less of Norris’ young man’s passion and more of the perspective and humor of a middle-aged man who’d already been through more than his share of adventures. Although Markham, his narrator, never seems to know what’s going to happen from moment to moment, the reader can’t help but catch the whiff of impending doom early on, and it’s no great surprise when it comes.

What I find most interesting about this book is simply the notion that a man with almost thirty years’ experience of working at sea, mastering the craft and sciences of navigation, sailing, propulsion, shipbuilding, and civil engineering, would pick up a pen and write this rollercoaster ride through the world of hype, gimmicks, and entrepeneurship. Riesenberg revels in the absurdity of Tangerman’s ventures and seems to have delighted in being able to pick the names of his characters: Punderwell Moore; Springer Platterly; Chauncey Wilber Tambey; Saxe Gubelstein; Jesspole McTwiller. (No one ever does find out what the initials P. A. L. stand for, though).

And then from this first novel, Riesenberg went on to write at least four others, all of them sweeping in scope, with dozens of characters up and down the social strata, and several (particularly

Endless River) fairly experimental for their time.

While I don’t think

P.A.L. should be considered a neglected masterpiece, it is a lively and self-confident novel than stands (in terms of literary merit) only a step or two back from Norris’ books (neither of which are really masterpieces, either, but better known for their historical importance). I’ve picked up three other Riesenberg novels, along with his 1937 autobiography,

Living Again, and plan to spend some of the next months reviewing the fictional output of this remarkable man. -

https://neglectedbooks.com/?p=1534

Felix Riesenberg, Living Again: An Autobiography, Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1937.

Felix Riesenberg, Living Again: An Autobiography, Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1937.

I’ve stocked my nightstand with a selection of books by Felix Riesenberg, whose first novel,

P. A. L., I wrote about several months ago. Riesenberg was a professional merchant seaman and civil engineer who took up writing somewhere in his thirties and went on to publish about a half dozen novels and an equal number of non-fiction books before his death in 1939. One might compare him to Joseph Conrad, who also switched from sea captain to writer, but Riesenberg is certainly not in Conrad’s class when it comes to fiction.

Still, I’m intrigued by what drove Riesenberg to make such a dramatic shift in occupations in middle age, and particularly by the fact that, as

P. A. L. demonstrates, he took considerable risks in his choice of subjects and approach. Although the majority of his books deal with life and work at sea, none of them seems to follow a predictable path. Riesenberg have not have had the mastery to be fully successful in his artistic ambitions, but he certainly didn’t lack the courage to take risks.

As Riesenberg’s 1937 autobiography,

Living Again: An Autobiography

, shows, risk taking was ingrained in his character. While still a teenager, he signed into merchant marine service, sailing around Cape Horn in a six-master and working his way up through the ranks, attaining his chief mate license and, later, his chief engineer and master licenses.

Riesenberg served on a wide variety of ships, from schooners to freighters to first-class Atlantic liners. His travels took him from the Far East to the Mediterranean and all over the Atlantic. But even these experiences weren’t enough for him, and in 1905, at the age of 26, he read an article about an expedition being organized by an American journalist,

Walter Wellman, to reach the North Pole by dirigible. “The scheme was crazy enough to seem workable,” Riesenberg writes. He paid a call on Wellman, who happened to be in Chicago at the same time as Riesenberg was taking leave at home, and a few days later, received a telegram telling him to report to Tromso, Norway to join the expedition as its navigator.

The expedition’s equipment loaded down four schooners, which sailed to Dane’s Island, near Spitsbergen. A base camp was built, including a massive hangar for the dirigible, but things fell behind schedule, the airship’s engines failed spectacularly when tested, and Riesenberg and two other men were left to spend the winter alone while the rest of the team returned to Norway. The next summer, the dirigible was finally completed and Wellman, Riesenberg and another man set off for the North Pole.

Within a few hours, though, they encountered powerful head winds and soon had to make an emergency landing on a glacier. A rescue party located them the next day. Riesenberg departed not long after they made it back to the base camp. “I returned, not a hero, not a bit the wiser–for it took years of contemplation before I was able to even bear the thought of setting down the circumstances of my disappointment.”

Back in New York, he enrolled in the civil engineering program at Columbia University after an uncle offered to help with tuition. He married soon after graduating, and the adventurer soon found himself scraping to stay afloat: “After marriage, things happened to me. I tried to save but could not manage it. Unexpected jobs, royalties and windfalls came to me often in the final minutes before the crack of disaster.” He worked on the construction of massive pipelines bringing water to the city. He worked for the Parks department until kicked out of the job with a change of administrations. He worked as a building inspector, which proved one of his more educational jobs:

Violations, reported by neighbors, policemen, and what not, consisted of fire escapes that were rusting apart, of fire doors unhinged and inoperative, or air shafts too small, of drains leaking, of the many things that can be wrong with any ramshackle structure. The job took me into places nothing else could have opened; no novelist could find a better entree to the steaming and often stinking heart of the bloated, untidy, but exciting city.

Then, in 1917, the sea called him again, and he was asked to take command of the

U. S. S. Newport, the floating campus of the New York Nautical School. Riesenberg was both ship captain and college dean. He reveled in the glories of the ship, a sparkling white three-master, one of the last sailing ships built for the U. S. Navy. While the war was going on, the ship was confined to Long Island Sound, but after the Armistice, he was able to take it on a long cruise down to the Caribbean.

Riesenberg left the command in 1919, but returned four years later for another cruise. This time, he took the students on a voyage of thousands of miles, all the way from England to the Canary Islands and the Bahamas. Along the way, they encountered a massive storm that nearly capsized the ship. You can read an account of the cruise by one of the students, A. A. Bombe, online at

http://www.sunymaritime.edu/stephenblucelibrary/pdfs/1923%20cruise%20uss%20newport.pdf.

In between and after, he kept moving from job to job–a year as chief engineer for the construction of the Columbia Presbyterian Hospital; somewhat longer editing the

Bulletin of the American Bureau of Shipping; and, increasingly, stories and articles for the likes of

The Saturday Evening Post. Riesenberg spares little space for his own writing. One novel he dismisses in a sentence as “a rotal flop, a complete and thorough failure.” His 1927 novel,

East Side, West Side

, though, was a hit and made into a film, one of the last big-budget silents, which earned him a time in Hollywood as a studio writer.

“Felix, why don’t you write a book about your life?” one of his editors asked him in 1935. So Riesenberg packed up his journals and diaries and headed to a small house on the beach near Pensacola. “After seven months on the edge of a warm and reminiscent sea,” however, “the truth came upon me with a feeling of dread–I was a stranger to myself.” Though he managed to set down the account that appears in this book, he confesses at the start that, “I look upon these things as strange occurrences, common, no doubt, to all of us.”

Despite the many colorful episodes and Riesenberg’s strong and direct prose style, however, that odd sense of detachment prevades

Living Again

and leaves it, in the end, a less than satisfying autobiography. The reader cannot help but get the sense that Riesenberg’s most intense experiences occurred during his early years at sea, and that most of what happened thereafter seemed anticlimactic.

Still, I will carry on with my navigation through Riesenberg’s novels. I just started

Endless River

, which Robert Leavitt described as, “a torrent that pours through a book—the torrent of Mr. Riesenberg’s thought and comment on life…. It swirls and eddies, formlessly; it gnaws at its restraining backs; it throws up a spray that gleams, now and then, with an unholy phosphorescence. And it tumbles along a burden of flotsam that is the most curiously assorted ever a river bore.” Clearly another example of Felix Riesenberg’s willingness to take risks. -

http://neglectedbooks.com/?p=1684

Felix Riesenberg, Passing Strangers, Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1932.

Felix Riesenberg, Passing Strangers, Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1932.

In his autobiography,

Living Again, Felix Riesenberg mentions his 1932 novel,

Passing Strangers, just once, calling it “a failure.” Riesenberg’s criticism is hardly any harsher than that of time itself, since the book has vanished along with most of his

oeuvre and has apparently never even earned a mentioned in academic articles on literature of the Great Depression.

Yet

Passing Strangers is a powerful specimen of the effect of the Depression on the creative mind. In the book, Riesenberg takes a cross-section of society and subjects it to the disruptive and erratic effects of a great economic collapse. As he put it in his preamble, “A group of people, caught in the mesh of cams and gears, are tossed about by the machinery of life.”

Riesenberg starts his story with “The Average Man,” Robert Millinger, a lowly elevator operator in the new and splendid Babel Building, the pride and envy of all Manhattan. Millinger is a perfectly working cog:

After a time people who entered and left the elevator, familiar or strange, no longer meant things to Mr. Millinger. They were merely presences. He responded to them without thought, or reason, but correctly. Clever as his car was, it was crude compared with that stranger flexible, self-oiling, economical machine, Robert Millinger, elevator operator No. 243, Imperial Holding Corporation. Residence 749 Taylo Street, Brooklyn. Married.

Millinger himself is a cipher, but he believes that makes him an invaluable source of insights into the common man, and fantasizes about being taken into the confidence of an important executive, such as Isidore Trauenbeck. Trauenbeck runs the Babel Building and dozens of other properties. “His day,” Riesenberg writes, “was marked by the grease spots of those completely squelched.” Even greater than Trauenbeck is his own boss, the mysterious tycoon, A. Thouron Clamson, an amalgam of Donald Trump, Howard Hughes, and John D. Rockefeller. Clamson puts Tom Wolfe’s “Masters of the Universe” to shame:

A. Thouron Clamson hadn’t a single title. He signed his name with a flourish, beginning with Clamson, weaving the A. Thouron into the device with a degree of skill grown from long practice. He owned in many things, almost endless things, holding control of such vast interlocking and intermeshing activities that great charts were prepared to keep the picture reasonably in hand. He always prepared to shift his money from one raft to another at a moment’s notice. He owned sixty percent of Mid-Continental Gas. Then he bought out the rival pipe line of Sioux Service, and suddenly dumped his M. C. G., pounding it down while booming Sioux. On the swing, he drew back all but five percent of the first company. These two were then combined and on the seventh day he rested from his labor. But the labor, of course, was done by others. He merely decided.

Riesenberg reaches down from Clamson to Millinger through a string of almost random connections, drawn in such a way that only a few of his characters share acquaintances. They are, as the title suggests, passing strangers, but they share one thing in common: all are affected in some profound way, by the stock market crash and the resulting depression. Millinger loses his job, is abandoned by his wife and daughter, and nearly dies of hunger and exposure on the streets of New York. Millinger’s wealthy cousin, Zekor, is forced to move from Park Avenue to a slum in Brooklyn and dies on a park bench, worn out by the relentless loss of property and self. Willy Jennings, the department store owner who takes Millinger’s wife, Launa, as his lover, finds his web of speculations and leveraged deals collapsing around him and jumps from his office window [Riesenberg

recounts one of these supposedly apocryphal suicides in

Living Again.] Millinger’s daughter, Diana, in turn, becomes Clamson’s mistress, until she sickens of his esthetic and moral excesses. Clamson experiences the it all as mild turbulence, not even bothering to buckle his seatbelt.

Riesenberg wraps everything up in a climactic disaster scene somewhat foreshadowing events at the World Trade Center, as radicals set off truck bombs and explosives in the subway system to protest the human destruction caused by capitalism. Clamson is assasinated as he sits in traffic in his limousine. Millinger’s daughter escapes from the chaos with a man who used to drive Zekor Millinger’s Packard. And, ironically, Millinger is rescued by a young woman who brings him to Clamson’s wife, a noted supporter of social causes.

While certainly less experimental than his previous novel,

Endless River,

Passing Strangers lacks nothing in comparison when it comes to ambition. Riesenberg didn’t have quite the technical mastery to bring off all he aspired to, but the book is never less than enthralling. I read it in just three days, sitting in cafes as my wife and daughter shopped around London during Thanksgiving. It demonstrates yet again that we need to find a place in our memories for the like of Felix Riesenberg, who may not always have succeeded in his literary attempts but deserves to be recognized as a bold American artistic adventurer. -

http://neglectedbooks.com/?p=1729