Richard Weihe, Sea of Ink, Trans. by Jamie Bulloch, Peirene Press, 2012.

In 1626, Bada Shanren is born into the Chinese royal family. When the old Ming Dynasty crumbles, he becomes an artist, committed to capturing the essence of nature with a single brushstroke. Then the rulers of the new Qing Dynasty discover his identity and Bada must feign madness to escape.

"Inexplicable, almost magical ... Weihe's sketches - created in a few words - trigger the imagination of the reader." Berner Zeitung "You feel that your are watching the painter at work. - Die Tageszeitung Sea of Ink is a novella that consists of 51 chapters in which we are provided with an overview of the life of Bada Shanren, an influential Chinese painter who lived in the 17th century. We follow Bada Shanren as he experiences the loss of power by the Ming Dynasty. From being a member of the royal family, Bada Shanren becomes a painter trying to remain unknown during the new Qing regime. This new Peirene novella provides a comfortable and interesting reading experience. I particularly liked seeing how Bada Shanren grows into his own over the 112 pages that are part of the book. Moreover, I liked how small details of his life, the production of his paintings, and philosophical (tao?) inspired life-lessons.

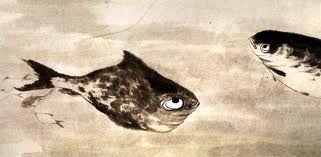

What surprised me most about the book is how well the descriptions of the process of painting worked, especially as most of these descriptions were accompanied with the resulting painting one or two pages later. Usually, I struggle with very visual descriptions in books and I quickly lose my interest. But in case of Sea of Ink I actually enjoyed reading and guessing what the result would look like. It is also why I am so grateful for the inclusion of 11 pictures of Bada Shanren’s paintings.

All in all, Sea of Ink was a very pleasant read. Nevertheless, it has this elusive quality that keeps you a little removed from the story and I felt little personal involvement in the characters or story. The book was interesting, and very very beautifully written (I could quote passage after passage for you, but I think they work best discovered in the book), but it lacked something that pulled me right in. Then again, quietly beautiful books are very worthwhile reads and this one certainly covers those aspects.

- irisonbooks.com/t

This is the third and final novella in Peirene's Small Epic series and they don't come much smaller or epic than this one. 107 pages including 11 illustrations make up 51 short chapters. Contained within those small numbers is the life of a man, the end of the Ming dynasty in China and a meditation on artistic inspiration that applies not just to the visual arts, maybe not just to the arts at all, but applies to everyone when examining what comes before action of any kind. That aspect of the book, and the fact that it is based on the real life of Chinese painter, poet and calligrapher Bada Shanren, mean that you might question how well it succeeds as a piece of fiction in the traditional sense (Weihe's Afterword and Notes on Sources show actually how well he has incorporated his research) but there is no doubt that it provides a calm and meditative read that will reward you with an enormous sense of relaxation if you can absorb it in a single sitting.

The year 1644 saw the end of the Ming dynasty which had ruled China for 276 years. The ruling family had spread far and wide but were slowly and systematically wiped out by the rising Manchu's. Those that had once wielded power were faced with the choice under the new Manchurian dynasty to collaborate or die. We follow the life of the man who was born Zhu Da in 1626, in the eleventh generation of the Yiyang branch of the Ning line of the royal family (Ning being the 17th son of Ming dynasty's founder). A sheltered childhood in the palace allowed him to develop his early prodigious gifts in poetry and art under the tutelage of his father. But with the end of the Ming dynasty and his father's death, Zhu Da is rendered mute, communicating only with his brush, before finally fleeing to the mountains, and the sanctuary of a monastery, leaving behind a wife and child, perhaps guided by wise saying, 'If you are guided by human feelings you will easily lose your way... but if you are guided by nature you will rarely go wrong.'

The opening of this novella is a little like the paragraph above, a potted history and a lot of 'plot' and I might seem to be spoiling things by giving so much away but the plot isn't really the thing. Zhu Da leaves his life as a prince behind, any returning images 'not memories, rather the dream of a life never lived.' Within the monastery he undergoes the first of his transformations, changing his name to Chuanqui, and beginning his next period of tutelage under the instruction of the Abbott Hongmin. The meat of the book is really in what it has to say about creativity, inspiration, art, expression and the position of the person who holds the brush. The Abbott has plenty of wise advice to pass on to his charge and his training is repetitive, physical and demanding. We might not think of a single, fluid swipe of the brush as a physical exertion but we get a real sense of the pain that comes from repeatedly practising movements and getting to the point where he can remove the conscious movement and allow the hand and brush to paint what is there. As his master explains at one point: "Ink is water rendered visible, nothing more. The brush divides what is fluid from everything superfluous."

The plot will catch up Chuanqui (who in turn changes his name to Xuege, then Geshan, Renwu, Lu, Poyun and finally Bada Shanren) who will have to feign madness in order to escape being assimilated into the new order when his identity is uncovered. The adoption of the face of madness, the near-constant name changing and the desire to disappear into the act of painting all throw up interesting thoughts about the position of the artist, particularly in a modern age when the cult of the artist as celebrity or brand is so strong. Bada Shanren has an interest in remaining undetected of course and actively avoids being identified (although he applies his stamp to each of his pictures) but he is constantly striving to locate who he is as an artist for himself. Again, his master will have something to say on the path of the individual artist looking at how to express themselves directly.

'...besides the old role models you also have your own: yourself. You cannot hang on to the beards of the ancients. You must try to be your own life and not the death of another. For this reason the best painting method is the method of no method. Even if the brush, the ink, the drawing are all wrong, what constitutes your "I" still survives. You must not let the brush control you; you must control the brush yourself.'

As I said at the top there are 11 illustrations of Bada Shanren's work throughout the book and one of Weihe's strengths is the way in which he technically describes the act of painting some of them. This might sound counter-intuitive but in the same way that Jean Echenoz used plain description to realise the works of Ravel into the reader's mind, Weihe describes the technique behind the paintings of Bada Shanren, something particularly important in a painting style which is all about technique and what can be achieved by single strokes, changes in pressure and the use of the right ink.

In the centre of the paper he painted a fish from the side, with a shimmering violet back and a silver belly, the tail fins almost semicircular like the bristles of a dry paintbrush. The fish's moth was half open, as if it were about to say something. It's left eye peered up to the edge of the paper with an expression combining fear, suspicion, detachment and scorn.

The eye was a small black dot stuck tot he upper arc of the oval surrounding it.

The fish swam from right to left across the paper.

Bada painted this one fish and no other, then out his name to the paper.

He had perished long ago, but he was still alive. All he feared now was the drought, when the ink no longer flowed and life had been worn down to nothing.

That is how he saw himself.This novella is perfect reading for any visual artist (I have already passed my copy on to just such a person) but I would argue that its lessons and the thoughts it provoke would apply to anyone working in just about any field of the arts, where inspiration and creativity are as capricious and slippery as a live fish in the hand. In a modern world where everything seems to run at a hectic pace and demand is such that we might simply churn things out rather than take our time there is a lot to be said for giving this book the time it requires to read from cover to cover. That in turn might help us to appreciate the time we should take before making the first stroke, for...

....Is the whole drawing not contained in the first stroke? It must be considered long in advance, perhaps a whole life long, in order to bring it to the paper in one fluid movement at the right moment, without the need or ability to correct it. - justwilliamsluck.blogspot.com/

Sea of Ink, by the Swiss writer Richard Weihe, is the third book in Peirene’s Small Epic series which also includes The Brothers. Set in seventeenth century China between the final days of the Ming dynasty and the beginning of Manchu rule, it follows the life of Bada Shanren. Bada Shanren was born into a minor branch of the old Ming royal line, and when the new dynasty comes to power he is forced to flee and become a monk. In his new life he takes up painting, following the tuition of his monastic master he begins to paint scenes from nature with simple black brush strokes, eventually becoming a renowned artist. In the afterword to the book Richard Weihe explains something of the life of the real artist Bada Shanren. In this elegant novella he blends historical fact and fiction to powerful effect. The story is full of sadness at what Bada has lost in a former life, but also determination to be the best painter possible and to remain independent from the new regime. He refuses to be co-opted by the government that he sees as illegitimate.

The novella contains simple, almost technical descriptions of the motion that Bada Shanren makes with his brush on the paper, but then follows them with some astonishing and surprising copies of Bada Shanren’s actual paintings.

Starting in the bottom-left hand corner, he made a bold stroke across the entire width of the paper and then continued in a right angle upwards, slowly lifting his hand so that the line, after a slight curve to the left, finished in a point. Around this point he planted three deep-black, almost round blobs, inserting between these some delicate, parallel, wavy lines with the tip of the brush.

Interspersed throughout are elements of Confucian thought that Bada develops through his simple life.

‘When you talk like that you are forgetting that besides the old role models you also have your own: yourself. You cannot hang on to the beards of the ancients. You must try to be your own life and not the death of another. For this reason the best painting method is the method of no method. Even if the brush, the ink, the drawing are all wrong, what constitutes your “I” still survives. You must not let the brush control you; you must control the brush yourself.’

Sea of Ink is wonderfully immersive and the format is perfect for a couple of hours of complete escapism. Richard Weihe’s writing is sparse enough to leave Bada Shanren’s painting to speak for itself, and in just one hundred pages encapsulates an historical saga and a rich life.- Graham MyBookYear

A lovely surprise popped through my letter box a few days ago: 'Sea of Ink' by Richard Weihe from the lovely people at Peirene (pronouced 'Pie-ree-nee') Press.

'Sea of Ink' is the first English translation of 'Meer der Tusche' which was published in Switzerland in 2005 and won the Prix des Auditeurs de la Radio Suisse Romande in the same year, and is about Bada Shanren, a 17th century Chinese painter who starts life as a member of the aristocracy, but goes on to take many guises (and different names!) whilst forging his own path through the creative and contemporary world. He becomes, to name a few, a monk, a madman, a father and a husband, so this book gives you a pretty thorough account of life at the time, although most of it is fiction as you can imagine that 17th century Chinese non-governmental sources are few and far between... Structurally, it is 51 short chapters arranged as a 118 page novella, the idea being across the Peirene range that you can read these little gems in an evening, or the same amount of time you might use to watch a film.

Rather than film time, it took me a bath and a train journey to delve through to the end, and a very calming and enjoyable read it was too. I don't know if it's because Bada Shanren is a fairly serene figure or because the Chinese landscape is so poetically evoked, but I found this book to be a profound quiet spot in two quite busy days. The language is lovely, the tale is simply told and I loved that Weihe imagined the process of Bada Shanren painting his most famous pictures (I've included some below) and included the pictures also, so you can read the process of Bada Shanren painting his most famous pictures whilst tracing the lines with your eyes on the opposite page. The novella-length feature that is common to the whole Peirene series is inspired - what a nice feeling to zip quietly through a lovely book in two hours, a small interlude in the midst of my mammoth, if wildly satisfying 'A Suitable Boy' Readathon which is going to take me at least a month more yet :)

My only slight criticism might be to do with the translation - some of the sentences feel too short to let the mood really flow - but in large part it's excellent; the poetic eloquence of the story was conveyed very well by the translator, which after all is the most important thing.

As a side thing, it was a real novelty for me to pick up a book and not to have my attention grabbed immediately by the fellow author boosters and recommendations that normally wave from the cover and chatter through the first few pages, as if buying/borrowing a book wasn't even to imply interest and that we might still need convincing. I found it very refreshing to see a book and feel that the publishers had enough confidence in it to leave this off and say, yes, this book is good enough and brave enough to stand on its own. The cover is gorgeous too - taking the sum of its parts, it's a really lovely thing.

This book is actually one of the thematically linked trio of books that Peirene are publishing in 2012 - the others are 'The Murder of Halland' by Pia Juul and 'The Brothers' by Asko Sahlberg, comprising the 'Small Epics' series; 2011's series was 'Male Dilemma' and 2010's 'Female Voice'. All are European novels in translation, and most (if not all) were launched with a variety of literary salons and elegant evenings with the author attached, so Peirene seems to provide a very sophisticated and total experience. I'm excited. I actually own one of the books from the 'Female Voice' series although I have yet to read it, but I think I'll be bumping it up the series so I get to it soon. - www.tolstoyismycat.com/

Some say novellas are sometimes the easiest to read. They are generally one hundred and twenty pages long, sometimes even shorter than that. Yet when I picked up the novella, "Sea of Ink" by Richard Weihe and sat down with it, I didn't realize that it would be difficult for me to get through it, only because I did not want it to end and also because at some places it was a complex read. "Sea of Ink" is a novella of 50 short chapters and 10 sketches. It is about the life of Bada Shanren, one of the most influential Chinese painters of all time. Richard Weihe combines fact and fiction seamlessly in this novella, only to enchant and mesmerize readers. That was the highlight of this novella for me.

Bada Shanren is but obviously an artist and like most artists, he needs his space and time to create. What Richard Weihe does through the book is give the artist that. He almost creates a world through Shanren's 10 selected ink drawings and weaves the story through art. He merges the two art forms and keeps words minimal.

The plot of the book is about Shanren, a 17th Century Chinese painter, who starts his life as a member of aristocracy, but takes on many guises and names, just so he can keep his art alive in the world. Shanren was a part of the time when the Ming Dynasty crumbles and that is when he goes into hiding so he can be alive and safe. He took on on several roles - of a father, a husband, a madman, and a monk, just so he could paint, and only because the hunger of the artist was unrelenting. The most beautiful part about his artwork is that he wants to capture nature with a single brushstroke. This is beautifully seen in his works that form a part of the book. What will astound you as you go further into the book is that all of this had actually happened (or at least most of it).

Now, let me tell you about the writing. I loved it because it was clear and not beating around the bush. Maybe that is why novellas can actually bring out the most of what a writer has to say. The novella speaks almost in poetic prose - describing the life of the painter - the way he feels, what he does and how can alienation feel, with the taking of so many guises and names. At some level, you need not be an artist to relate to Shanren's life and perspective. That is the beauty of Weihe's writing.

There were times in the book, when I had to go back to the sketches and then correlate them with the prose. It seemed a bit cumbersome however that is the idea of the writing (if it is). Besides this, for me the book has been a delight. The translation by Jamie Bulloch from German has been superbly done - so much so that it didn't feel like a translated work. November could not have started any better than it did with this small gem of a book. - Vivek Tejuja at amazon.com reviews

If all the world was a stage to Shakespeare, for 17th century Chinese painter Bada Shanren it was the open sweep of a blank canvas.

Little is known of Shanren, the man, despite his legacy of 129 dated pictures and albums featuring exquisitely minimalist paintings and calligraphy, all executed with ink on paper.

Inspired by a single reproduction scroll painting given to him years ago, German author Richard Weihe has reinvigorated one of the most influential Chinese artists of all time and set him afloat on a ‘sea of ink.’

That journey is captured in a compelling, two-hour reading experience, a 106-page novella which paints a portrait of a life in 51 short chapters and sketches the soul of an artist through eleven of his breathtaking pictures.

Sea of Ink is a tale told in shades of light and darkness; it uses fact and fiction as its medium and enables one man’s personal history of determination and creativity to be played out against a framework of lost splendour, political savagery and spiritual awakening.

We meet Shanren, born Zhu Da, in 1626 when he is still a prince of the Ming dynasty, raised in a palace in Nanchang surrounded by wealth and privilege.

But when the old dynasty crumbles, he flees the Qing conquerors and takes refuge in a monastery, feigning madness to evade recognition. But his true calling is art and under the tutelage of the master Abbot Hongmin, Shanren becomes an artist, taking the new name ‘ba da shan ren,’ meaning ‘man on the mountain of the eight compass points.’

His goal is to capture the essence of nature with a single brushstroke, finding his inspiration in all forms of life, from the grandeur of a mountain to two rival spiders spinning a web of meaning across his simple canvas.

‘The first brushstroke is the foundation,’ he tells his pupils, ‘it is the internal law of the external movement.’

In Weihe’s capable hands, we witness the magical, physical creation of the paintings, the brush’s ‘gently winding movement,’ the bristles dripping with ink, the slow lifting of the artist’s arm and the spare brushstrokes that make up the whole.

Through each carefully balanced, descriptive, considered word and phrase, Weihe draws Shanren’s pictures, recreating with startling clarity an image that appears in literal line and form on the turn of the page.

Sea of Ink is a serene reading experience, an author and artist in perfect harmony, and all brought to fruition for English-speaking readers through the subtlety and fluidity of Jamie Bulloch’s superbly sympathetic translation.

Intriguing, elegant, awesome in its precision and uplifting in its sheer beauty, this is a book to read, enjoy... and then read again. - Pam Norfolk

I haven’t reviewed anything from the excellent Peirene Press for some time and when Sea of Ink arrived through the post I was pleased to find another beautifully produced novella, this time about the life of Bada Shanren, the leading exponent of what we now call “Chinese brush painting”, from the Ming Dynasty.

Bada Shanren was born into the Chinese royal family just as the old Ming Dynasty was crumbling. Forced into exile to escape the new Qing Dynasty Bada Shanren devotes himself to a form of painting which tries to capture the essence of an object with single brush-strokes.

He covered the small piece of paper he had laid out with a few rapidly executed vertical and horizontal strokes. In the right half of the picture he interrupted a downwards sweep by lifting the brush and, from the centre of the paper, painted a broad line which he guided along a gentle incline to the right-hand edge of the paper . . . now he could see two stones on coarse grass, nestling up to a larger boulder. In their shelter grew a modest mountain flower with many leaves watched over the the rough-edged rock. He recognised himself not in the boulder but in the tiny plant. The fortune to be oneself was sufficient for the plant to sit at the centre of the world.

I know a little about Chinese brush painting but through reading this book I now realise the depth of ascetic and spiritual training which the great masters of the art submitted themselves to. Bada Shanren went through years of discipline in the monasteries of northern China, becoming a master of the Tao. For many months he just drew circles with his brush and then took six years out from his painting to go to rebuild a derelict monastery, high in the Fengxin mountains.

After many months of hard work on the reconstruction, Bada Shanren “woke and mixed up some ink and picked up one of his finer brushes and painted a lotus flower growing out of a swamp, its beauty being unfurled in the clear, sharp outlines”. He took the painting to his Master who told him that while he had captured the “floweriness of the flower and the wateriness of the water” that there are still lessons to learn. When Bada Shanren says, “Which ones?”, the Master tells him that it is not for him to say what the lessons are – “you must happen upon it for yourself”.

The whole approach to Chinese painting is very different to the artistic world of today with his countless courses and DVDs offering advice on how to paint a tree or a portrait. My local community centre runs a Chinese brush painting class but having read this book I can’t see how contemporary Western artists can get anywhere near the essence of the art – all they can do is copy the outward appearance. Whether the results are distinguishable from the real thing is an open question, because the simple forms of the art are actually quite simple to reproduce.

I suppose people who convert to Buddhism have the same problem – you will always be a “western person who studies Buddhism” unless you immerse yourself in the rigorous training which natural-born Buddhists undergo. However much Buddhist language a Westerner uses their experience must always be essentially different to the experience of a native Buddhist (I of course greatly respect those who do go through the immersion required).

The book consists of 50 very short chapters and reproduces about ten paintings by Bada Shenren. Although it is a short book, there is something about it which made me linger over each chapter, pausing to follow the strokes of Bada Shanren’s pen as his techniques are described. While the book is fiction, it is obvious that the author has spent a great deal of time recreating the life of Bada Shanren and trying to get into his thought processes.

Richard Weihe specialises in biographies of influential artists and Sea of Ink won the Prix des Audituers de la Radio Suisse Romande. The translator, Jamie Bulloch, is building a very good reputation as is shown by his page on the Goethe Institute website which says that “his self-effacing approach to the original text will undoubtedly allow the rhythm of the sentence to come through in English”. That is certainly the case here.

There is a wonderful gallery of Bada Shanren’s paintings on the Chinese Online Museum. The illustration above comes from Wikipedia in order to avoid copyright issues. - acommonreader.org/

The Ming Dynasty, was the ruling dynasty of China from 1368 to 1644 and rose from the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty. The Empire of the Great Ming, reigned for 276 years and has been described as "one of the greatest eras of orderly government and social stability in human history", it was the last dynasty governed by the ethnic Han Chinese. The capital Beijing fell in 1644 to a rebellion led by Li Zicheng who established the Shun Dynasty, although this was short-lived as Li Zicheng failed to realise his ambitions and was defeated at the Battle of Shanhai Pass, by the joint forces of the Ming general Wu Sangui and Manchu prince Dorgon. After his defeat he fled back to Beijing and proclaimed himself Emperor of China, then left the capital rather rapidly, the Shun dynasty ended with his death in 1645. The Shun reign was superseded by the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty, although scattered remnants of Ming supporters held out, despite losing Beijing and the death of the emperor. Nanjing, Fujian, Guangdong, Shanxi, and Yunnan were all strongholds of Ming resistance. However, there were several pretenders for the Ming throne, creating a weak and divided force, until one by one each bastion of resistance was defeated by the Qing until 1662, when the last real hopes of a Ming revival died with the Yongli emperor, Zhu Youlang.

This is the background to Sea of Ink, the story of how Zhu Da, the prince of Yiyang, distant descendant of the Prince of Ning, the seventeenth son of the founder of the Ming dynasty, became Bada Shanren, widely regarded as the leading painter of the early Qing dynasty and a huge influence on Chinese painting from the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou (mid-Qing period), the Shanghai School in the late Qing, and even two hundred years after his death his work has influenced 20th century Chinese painting, including Wu Changsuo (1844-1927), Qi Baishi (1864-1957), and Zhang Daqian (1899-1983).

Born Zhu Da in 1626 into a family of scholars, poets and calligraphers, Zhu Da's childhood was one of untroubled bliss, surrounded by the wealth and glamour of a prince and relative, although a distant one of the founder of the Ming dynasty. At the age of eight he had begun writing poetry, and was considered a child prodigy, as he had taken to painting from an early age, spoilt and admired life looked wonderful. All this would come crashing down when he was in his teens, as the Manchu's gained control of the country, violently cutting down all that stood in their way. He was eighteen when they took Beijing and nineteen when their forces occupied Nanchang, the seat of power for his family.

At some point during this time frame Zhu Da, fled his home taking refuge in a Buddhist temple and changing his name to Chuanqi, here he would remain, burying himself in Buddhist teaching. In 1653 he was admitted to a small circle of pupils under the tutelage of the Abbot Hongmin, attaining his masters examination and now empowered to pass on tenets of Buddhist wisdom to younger scholars.

Life for Chuanqi, became one of contemplation, although sometimes curiosity got the better of him and he visited the local town, wandering the streets and gesticulating wildly and alternating between fits of laughter and tears, before falling down drunk and senseless in some tavern, giving the impression to all who saw him of some madman. It was 1658 before he took up the brush again and started studying painting.

In fifty one beautifully crafted chapters, this book manages to capture the life of not just one of China's greatest exponents of the Shuimohua* style of painting, but a man who was an enigma, a spoilt and adored Prince to Buddhist abbot, madman to respected artist, poet and philosopher, all told with a use of language that has wonder - whether of life or of art, as vital an ingredient as the ink printed on the page.

"On one occasion his father made him step barefoot into a bowl of ink and then walk along the length of a roll of paper. To begin with, Zhu's footprints were wet and black; with each step they became lighter until they were barely visible any more. Then he hopped from the paper back onto the wooden floor. His father took a brush and wrote at the top of the scroll: A small segment of the long path of my son Zhu Da. And further down: A path comes into existence by being walked on."

There were times whilst I was reading this that reminded me of In Praise of Shadows by Jun'ichiro Tanizaki, not so much in the writing but more the aesthetic ideal (Iki*) behind it. This is partly down to the subject matter of art, particularly in the descriptions of the eleven pictures by Shanren featured in the book. But the main reason is that like the art itself, this book is composed of minimal brushstrokes that describes Bada Shanren's journey with just enough light and shade to reveal the tale in all its depth, allowing the tale to almost tell itself, and again like the art work it does this a wonderful degree of subtlety. - PL at amazon.com reviews

The premise of this book is delightful: a novella in 51 short chapters, describing the life of famous 17th-century Chinese painter Bada Shanren, partly through his paintings themselves, which are reproduced in the book. The writing in places was quite beautiful, but as a novella it didn’t really work for me. I’ll attempt to explain why.

Part of it, I think, is the difficulty of describing art in words. I had a similar problem with the descriptions of jazz in the Booker-shortlisted Half Blood Blues last year – I wrote then, “No matter how good the descriptions are, it’s really hard to convey the beauty of music through the written word. There are lots of passages in this book about Hiero blowing a high C or Chip playing crisp and clean on his drums, but I still couldn’t hear the music.

It was exactly the same for me here. I read something like the following:

He covered the small piece of paper he had laid out with a few rapidly executed vertical and horizontal strokes. In the right half of the picture he interrupted a downwards sweep by lifting the brush and, from the centre of the paper, painted a broad line which he guided along a gentle incline to the right-hand edge of the paper, then made a straight brushstroke from the end of this down to the bottom with a single fluid movement of the hand…

Nothing wrong with the writing, but I couldn’t really see the painting – until I turned the page and was presented with an image of the painting itself, which looked completely different from the half-formed image in my head, and which at a glance communicated far more than the preceding page of description (I only reproduced a small portion of it here). I know that the point was to get behind the images, to add another dimension to them by imagining what the painter was feeling as he made those brush-strokes. I applaud the aim, but for me it didn’t really work.

I should say, though, that it seemed to work for others – I appear to be out on a limb here. Haven’t seen too many reviews yet, but the ones I have seen are mostly positive. Check out, for example, Little Words or My Book Year. And Die Tageszeitung said “You feel that you are watching the painter at work.” This was clearly a major aim of the book, but I didn’t feel that at all, and so the descriptions of brushstrokes became quite repetitive.

Another problem I had was that 51 chapters in 100 pages means, of course, that the chapters are incredibly short – in some cases just half a page. Yet each chapter does deal with a separate episode in the painter’s full and varied life. The result is that the narrative feels episodic, not a story but a series of separate anecdotes, none developed very fully.

For example, the blurb for the book states “In 1626, Bada Shanren is born into the Chinese royal family. When the old Ming Dynasty crumbles, he becomes an artist, committed to capturing the essence of nature with a single brushstroke. Then the rulers of the new Qing Dynasty discover his identity and Bada must feign madness to escape.” It sounds intriguing, but the feigning madness and escaping all take place in a single chapter of less than two pages. They find him, he feigns madness, he escapes. Then it’s on to the next thing. I think the book would have worked better if the author had described a few key events from the painter’s life, rather than trying to cover everything and doing so only thinly. I hate to say something like that, because I know this is the book the author wanted to write, but that’s my take on it.

Having said all that, there were things I liked about Sea of Ink. There were some beautiful passages, like the painter as a boy learning from his father, who never speaks a word and yet manages to communicate. I loved the image of the boy stepping into a bowl of ink and walking along a long scroll, his footprints getting lighter with each step, and his father then writing on the scroll: “A small segment of the long path of my son Zhu Da. A path comes into existence by being walked on.”

There’s a real poignancy to the young painter’s abrupt loss of his wife and son as the Ming dynasty crumbles and he is forced into hiding, and I loved how these memories were handled later, as the painter, now a monk, starts to become detached from them but can never truly relinquish them. The writing is simple, spare and sometimes beautiful, a perfect accompaniment to the paintings in which so much is communicated with only a few strokes of black ink.

I’d love to hear from anyone else who’s read the book and has a different take on it. Or of course, agreement is always good! Or if you haven’t read it, does it sound like the sort of thing you’d like? Let me know in the comments below. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a few images (which you can click to enlarge) from the artist, Bada Shanren: - andrewblackman.net/

www.chinaonlinemuseum.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.