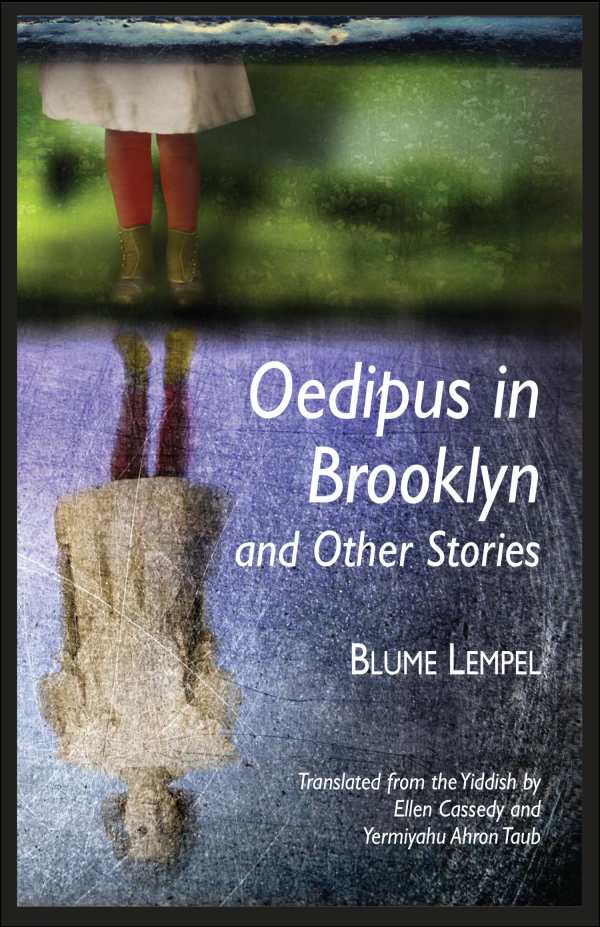

Blume Lempel, Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories, Trans. by Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub, Mandel Vilar Press and Dryad Press, 2016.

Several stories can be read on-line: "The Little Red Umbrella" in Brooklyn Rail, "Neighbors over the Fence," in Pakn Treger, "Pastorale," in K1N, and "The Debt," in In Geveb."

Blume Lempel is a fearless storyteller whose imagination skilfully moves between the realistic and the fantastic, the lyrical and the philosophical. Her subjects like her settings - Paris, Poland, Brooklyn, Tel Aviv, California - range widely. A Holocaust survivor speaks to the shadows in her garden; a pious old woman imagines romance; a New York subway commuter forges a bond with a homeless woman; a middle-aged woman opens her heart on a blind date; an argumentative couple gets lost in a blizzard; and in the title story, a mother is drawn into an incestuous relationship with her blind son. Readers of these superbly translated stories by Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub are in for a stunning literary journey.

"A splendid surprise and a significant revivication of a brilliantly robust Yiddish American writer." - Cynthia Ozick

“I am a housewife, a wife, a mother, a grandmother—and a Yiddish writer. I write my stories in Yiddish. [. . . ] Because I speak Yiddish, think in Yiddish. My father and mother, my sisters and brothers, my murdered people seek revenge in Yiddish.” (215)

There was a time when book-length translations from Yiddish were not such a rarity. Commercial publishers and smaller independent presses once saw a market for the likes of Sholem Asch, Chaim Grade, or Israel Joshua Singer. These days, however, translations from Yiddish seem to be entirely the preserve of a dwindling handful of university presses. In this context, the release of Blume Lempel’s Oedipus in Brooklyn, co-published by independent presses Mandel Vilar Press and Dryad Press, comes as a welcome breath of fresh air. Doubly welcome is the fact that Lempel has arrived into English at a time of increased appetite and enthusiasm for rediscovering the works of neglected female writers.

Blume Lempel (1907-1999) was one of Yiddish literature’s genuinely unique voices and this volume, comprising a selection of twenty-two stories taken from Lempel’s collections, a rege fun emes (A moment of Truth) 1981, and balade fun a kholem (Ballad of a Dream) 1986, gives the reader a taste of her range and thematic preoccupations. Lempel was a controversial writer, not just for the fact that she dealt with taboo topics such as incest, abortion, madness, suicide, etc. but for the unsettling candor and clarity with which she shared her inner world. Lempel’s essay “The Fate of the Yiddish Writer” rounds out the collection, serving as a fitting coda. In it she defines her writing as, “the putting down on paper of that which will not leave me in peace” (217).

Indeed it is this same inability to find peace that unites Lempel’s protagonists, a disparate collection of bag-ladies, beggars, refugees and retirees. Each is haunted by the traumas of the past, whether it be memories of war and genocide in the old country, or the smaller tragedies of modern life in France or America.

Lempel’s prose is muscular, unflinching, and uncompromising, capable of striking shifts in tone . . .

Before returning to the big city to continue his instruction in the ways of the world, Yosip presented her with a watch [. . . ] Every time she set the watch ahead, the hands turned backwards of their own accord. When she reached midnight, Sorke was standing before an open pit. Naked, ashamed, more dead than alive, she was waiting for someone, she knew not whom. A direct descendant of primeval man ripped the watch off her wrist. Dressed in a brown uniform and white gloves, he whistled a melody that had once moved her to tears. (157)

This tendency to lurch from the lyrical to the grotesque, often with dizzying unpredictability, is one of the qualities that give these stories their power.The translators Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub are both authors in their own right (Taub is a poet, while Cassedy is an accomplished prose writer) and together they produce a translation which is sharp, vivid, and polished. Their translation is particularly strong in those moments when Lempel dwells on images of horror and brutality:

Men hot dertseylt, az nokh als kind hot ir eygener foter ir di oygn oysgestokhn. In tsayt fun hunger hobn eltern farkriplt zeyere eygene kinder, zeyer vayber, un oft mol zikh aleyn opgeshnitn an oyer, a fus, opgehakt a hant, kedey tsu dervekn barmhartsikeyt fun di velkhe hobn zikh gekont farginen optsushporn a shtikl broyt dos khayes tsu derhaltn.

It was said that her own father had put out her eyes when she was a child. In the years of famine, parents did cripple their children, their wives, even themselves, chopping off an ear, a foot, or a hand in order to stay alive by arousing the sympathy of those with a crust of bread to spare. (158)

Even those stories that do not touch on violent events directly are tinged with a faint patina of unarticulated suffering. When dealing with certain themes, however—changing sexual mores, for example, or the bitter culture-shock of old-age—Lempel throws in the occasional pinch of irony, a dash of self-deprecation.As sacrilegious as it may be to say, the book could have benefited from being shorter—not that any of its contents should have been excluded, but there is a certain “homeopathic” quality to Lempel’s prose insofar as it is more potent in small doses. The reader is therefore advised to consume these stories in moderation: binge-readers run the risk of becoming numb to Lempel’s tonal shock-tactics, to the detriment of some very strong stories in the latter half of the collection.

Stylistically, Lempel is one of a kind, but the pantheon of forgotten female Yiddish writers is still densely packed with contenders, waiting for their chance to be rediscovered. If the current volume finds the readership it deserves, then it is not unrealistic to expect more of Lempel’s stories to appear in English at some point. And, with a little luck, perhaps some day readers will come looking for the next Blume Lempel. - Daniel Kennedy

https://readingintranslation.com/2017/11/15/trauma-ballads-blume-lempels-oedipus-in-brooklyn-and-other-stories-translated-by-ellen-cassedy-and-yermiyahu-ahron-taub/

Blume Lempel (1907-1999) was born in Khorostkiv (now Ukraine). She immigrated to Paris in 1929 and fled to New York on the eve of World War II. She wrote in Yiddish into the 1990s. Her prize-winning fiction is remarkable for its psychological acuity, its unflinching examination of erotic themes and gender relations, and its technical virtuosity. Mirroring the dislocation of mostly women protagonists, her stories move between present and past, Old World and New, dream and reality. This book is the first English language collection and translation of Lempel's stories and is based on a manuscript that won the 2012 National Yiddish Book Center Translation Prize

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.