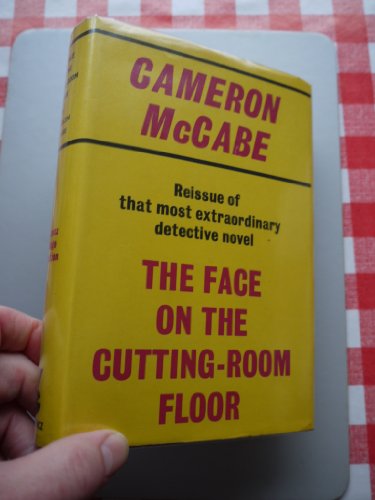

Cameron McCabe, The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor, Picador, 2016. [1937.]

The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor is a crime novel, arguably a whodunnit, by Ernest Borneman writing as Cameron McCabe. It was first published in London in 1937. The book makes use of the false document technique: It pretends to be the true story of a 38 year-old Scotsman called Cameron McCabe who writes about a crucial period of his own life during which several people close to him are murdered.

1930s King's Cross, London.

When aspiring film actress Estella Lamare is found dead on the cutting-room floor of a London film studio, Cameron McCabe finds himself at the centre of a police investigation. There are multiple suspects, multiple confessors and, as more people around him die, McCabe begins to perform his own amateur sleuth-work, followed doggedly by the mysterious inspector Smith.

But then, abruptly, McCabe's account ends . . .

Who is Cameron McCabe? Is he victim? Murderer? Novelist? Joker?

And if not McCabe, who is the author of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor?

"A dazzling . . . unrepeatable box of tricks . . . The detective story to end all detective stories." —Julian Symons

The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor is a weird, funny, perverse exercise in literary messing-about. It's a murder mystery that pulls the rug from under the reader, then pulls the floor from under the rug, then questions whether the floor was even there. It's a great, and baffling, experience, and the less you know about it beforehand, the better. - Mark Watson

This extraordinary work of postmodern fakery from the “golden age of detective fiction” was last reprinted 30 years ago, and in the intervening decades has acquired a legendary status. Introducing the book to those who haven’t read it yet, without revealing too many of its various secrets, is not an easy task.

It would be a terrible breach of protocol, after all, to give away the ending of a mystery story; and yet it would be hard to decide, in any case, what the “ending” of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor actually is – one of the book’s many peculiar qualities being that the enigmas surrounding it do not come to a halt on the final page.

In this novel, reality and fiction bleed into one another in the most disorientating way. Of course it’s – on one of its levels – a murder story, so I will not do anything so crass as to reveal the identity of the murderer; but the identity of the author – which lay hidden for more than 30 years after publication – is in some ways the central mystery, and the more intriguing one. There seems to have been no particularly feverish rush of speculation when the name “Cameron McCabe” appeared on the British crime-writing scene, for the first and last time, in 1937, even though several reviewers remarked on the unusual nature of his book.

It was enthusiastically reviewed by Ross McLaren and Herbert Read, who called it a “detective story with a difference”. Mention was made of the fact that the story did not proceed or indeed resolve according to the normal rules of detective fiction; that the author’s name was also the name of the principal character, and that the concluding fifth of the book was in fact an epilogue, purportedly written by a journalist friend of the narrator’s, commenting on its literary qualities and setting it within the context of recent trends in crime writing.

But just as much attention was focused on the story, which centres on an act of murder at an unnamed London film studio. An actor called Estella Lamare, already effectively killed off by a vindictive producer who has decided to excise her role completely from his latest picture, is found dead in the cutting room: her death has been captured on film by an automatic camera but the reel has gone missing. The subsequent investigation ranges from the streets around King’s Cross to the nightclubs of Soho, from tranquil, verdant Bloomsbury to the docks of the East End.

If “Cameron McCabe” was praised for the originality of his first entry into the crime genre, and for his novel’s strong sense of place, reviewers might have been surprised, and even more impressed, had they learned upon whom they were bestowing their acclaim. For the author of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor was only 22 years old when it was published and just four years earlier he had barely been able to speak a word of English.

His name was Ernst Wilhelm Julius Bornemann – subsequently anglicized to Ernest Borneman – and he had arrived in London as a communist refugee from Nazi Germany in 1933. In Berlin he had already made the acquaintance of Bertolt Brecht and worked for Wilhelm Reich’s Socialist Association for Sexual Counselling and Research. Somewhere along the way, either in Germany or London or both, he also worked as a film editor and acquired a reputation as a virtuoso of the cutting room. Borneman was widely read in European literature and, once settled in London, wasted no time bringing himself up to speed with developments in English-language writing, discovering a particular affinity with Hemingway and Joyce, not to mention American crime writers such as Carroll John Daly and Dashiell Hammett. This presumably explains the distinctive, sometimes highly eccentric style of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor, which despite being set in an English film studio of the 1930s (which evokes images, perhaps, of genteel musical comedies performed in perfect RP accents), combines laconic, hardboiled dialogue with extended stream-of-consciousness passages, all filtered through the skewed phraseology of someone whose acquisition of English was still, to some extent, a work in progress.

Borneman was a man of formidable intelligence who, like many a postmodern writer before and after him, loved the narrative energies of crime fiction while wanting to remain aloof from its conventions and simplicities. This is the tension that explains, I think, the formal idiosyncrasies of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor.

It begins briskly enough, with a crisp, punchy dialogue between narrator McCabe and producer Bloom, followed by an important chance encounter with a stranger outside King’s Cross station, on “one of those last evenings in November with the feel of July or August and the sky orange and heavy”. We then get a long and evocative sequence following our hero on a night’s adventures through bohemian Soho, and then there is the discovery of the murder itself, the next morning. After that, however, things start to get weird. You keep expecting the story to move forward and it doesn’t, really.

Inspector Smith of Scotland Yard turns up to take over the case and we are drawn into a protracted battle of wills (alternately referred to as a “fight” and a “game”) between him and McCabe. The minutest details of the case – who saw what, who was where and at what time – are combed over again and again. Hardly any clues are offered, or deductions made. The story starts to become an exercise in reconciling different perceptions of the same event.

And then there is the epilogue. The idea of bringing in a (fictional) literary critic to offer an assessment of the manuscript doesn’t exactly suggest that McCabe is a disciple of Dorothy L Sayers or Raymond Chandler: instead it calls to mind Alasdair Gray and his slippery creation Sidney Workman, who often pops up at the end of Gray’s novels to provide a commentary and footnotes. And when McCabe’s critic starts making general observations about the crime genre, such as “The possibilities for alternative endings to any detective story are infinite,” we are reminded that only two years separate The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor from that true masterpiece of early postmodernism, Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds, whose opening paragraph concludes: “One beginning and one ending for a book was a thing I did not agree with. A good book may have three openings entirely dissimilar and inter-related only in the prescience of the author, or for that matter one hundred times as many endings.”

O’Brien’s motives for undermining fictional conventions in this way are lofty and inscrutable. One senses only an amused Sternean scepticism about the whole silly business of writing books in the first place. With Borneman, though, the underlying aesthetic is more (forgive the pun) earnest. Given the fact that he knew Brecht while living in Berlin and came under the influence of his writing, I don’t think it’s too fanciful to see some kind of Brechtian alienation technique being brought into play. Just as a later experimentalist, BS Johnson, would tear through the fabric of his novel Albert Angelo (by declaring “Oh fuck all this lying!”) in order to make a political point about the dishonesty of fiction, so Borneman here is drawing attention to the inadequacy of detective fiction to express the chaos, loose ends and ambiguities of real life.

This does not quite, however, make The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor “the detective story to end all detective stories”, as Julian Symons has claimed. For me, that accolade would have to go to Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Pledge, published in 1958, at which time it bore the subtitle (later discarded) of Requiem auf den Kriminalroman or Requiem for the Detective Novel. Most of Dürrenmatt’s book works superbly as a self-contained crime novella, and in fact the central story is a very faithful novelisation of his film script Es geschah am hellichten Tag (It Happened in Broad Daylight); but when turning it into a book, he also topped and tailed it with a framing narrative in which a writer of crime novels meets a cynical ex-detective in a bar, and after listening to his (true) version of the story, with its far less neat and satisfying conclusion, is left in no doubt as to the fatal short-comings of his own genre of writing. Dürrenmatt’s forensic demonstration is elegant, devastating and final. By comparison The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor’s increasingly flummoxing layers of repetition and variation, and the elaborate metatextual apparatus at the end, feel more like a brilliant 19-year-old’s roar of frustration at the limitations of the genre which he has chosen for himself.

And so, having apparently exhausted the possibilities of the detective story with his first book, what was Borneman to do next? Initially, at least, the matter was taken out of his own hands. As a German national living in the United Kingdom, not long after the outbreak of war he was apprehended and shipped off to an internment camp in northern Ontario. After a year of this, fortunately, his plight came to the attention of Sir Alexander Paterson, the British commissioner for prisons, who had met Borneman briefly in London, and recognised him when he came to Canada to inspect the camp. Paterson arranged for his release and put him in touch with John Grierson, who had also come to Canada to help set up the National Film Board. Before long, Borneman was working for the NFB in (where else?) the cutting room.

Graham MacInnes’s memoir One Man’s Documentary gives a vivid portrait of Borneman at work as a film editor. Watching him make sense of the vast mass of footage assembled for a naval documentary called Action Stations, MacInnes saw that this was someone “with an eye as clinical and detached as a lizard’s”, who approached his work with “a fine mixture of Teutonic exactitude and a Jewish sense of extrovert lyricism”.

We are dealing with a remarkable man, then, obviously: and yet I’ve barely begun to scratch the surface of his remarkableness. He was also, already, a leading authority on jazz (there is a lot of it in The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor) and his next publication was A Critic Looks at Jazz, a collection of journalism on the subject from his London days. He returned to Britain in 5the 1950s and worked as a jobbing screenwriter for TV shows such as The Adventures of Robin Hood. By now he had published two novels under his own name, Tremolo and Face the Music, a murder mystery set in the jazz world which was filmed in the UK in 1954. Another Borneman-scripted film from that year, Bang! You’re Dead, is a fascinating British thriller set in the world of villagers displaced and made homeless by German bombing, who still live in Nissen huts on an abandoned US army camp. In 1959 Borneman published Tomorrow Is Now, a cold war story described by the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum as “evoking at times both Ibsen and Shaw”, and which Borneman himself considered his best novel.

In the 1960s he returned to Germany, in an abortive attempt to set up a new state-funded TV channel and published his last two novels in English, The Compromisers and The Man Who Loved Women.

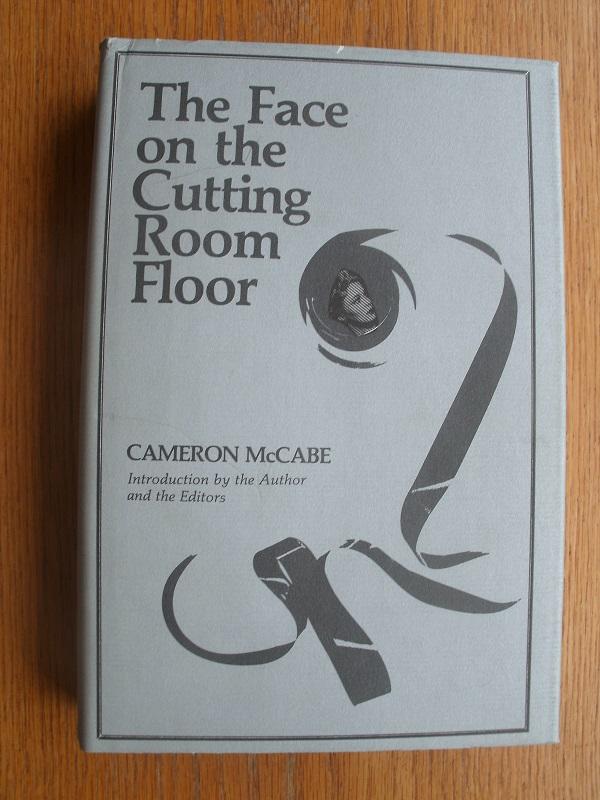

Finally Borneman settled in Upper Austria, where he lived in rural isolation in the village of Scharten. Isolation but not, by any means, obscurity: for now the final phase of his multifaceted career was under way, and he had made a considerable reputation for himself as an academic working in the field of human and particularly infant sexuality. By the time The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor was rediscovered and reissued in the early 70s, attracting extravagant praise from such writers as Symons and Frederic Raphael, Borneman was already the celebrated, sometimes notorious author of Lexikon der Liebe und Erotik and the monumental Das Patriarchat, which became a key text of the German women’s movement. He continued to write, lecture and publish well into his 70s.

By the end of his life, Borneman had travelled an immense distance from his early, brilliant foray into detective fiction. Or had he? If we are to make sense of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor, in the end, perhaps we should see it, not as a postmodern intellectual prank, or a “dazzling box of tricks”, but as a work of wild and desperate youthful romanticism. By the time his part of the narration draws to a close, McCabe – Borneman’s alter ego – has reached a suicidal frame of mind. Hopelessly in love with a woman who thinks nothing of him, he reflects that there is “No way out for a man once a woman has got hold of him … It will get you in the end.”

In 1995, to mark his 80th birthday, Ein Luderlichtes Leben (A Wayward Life), a festschrift devoted to Borneman’s life and work appeared, with a cover that showed him standing, fully clothed, next to a naked female model. The book had been compiled by a colleague of Borneman’s, who was also his lover at the time. Before long, however, their affair was over, and in June of that year Borneman killed himself. It had got him in the end. It seems that the 22-year-old Cameron McCabe and the 80-year-old Ernst Wilhelm Julius Bornemann were not so different after all. - Jonathan Coe

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/sep/02/whodunnit-and-whowroteit-the-strange-case-of-the-face-on-the-cutting-room-floor

The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor can be divided into three parts. For nearly 150 pages it follows a murder investigation, narrator Cameron McCabe -- a thirty-eight-year-old cutter at a London film studio -- describing the discovery of the victims and the investigation, by Scotland Yard Inspector Smith, into their deaths. After a series of quick and often dialogue-filled chapters, this section slows down towards its end, culminating in Smith spelling out the evidence and exactly what (he believes) transpired -- and fingering the guilty party. The novel then transitions, from whodunnit mystery to courtroom drama, describing first the run-up to the trial; then, in the novel's longest chapter, the trial itself, the accused, acting as his own lawyer, defending himself in a fight for his life; and a short coda chapter, after the verdict has been handed down, that neatly (and dramatically) ties things up and sees to a sort of justice being served -- in the destruction of two of the characters. That's not the end of the novel, however: it comes with 'An Epilogue as Epitaph', by an until then relatively minor character, A.B.C.Müller, which is where the novel first veers off and then goes completely off all traditional narrative (much less mystery) rails, this epitaph-chapter taking the whole genre down with it (and yet still providing most of its satisfactions, down to how it ends with an abrupt bang).

The story begins with a face left on the cutting-room floor, narrator Cameron McCabe directed by his boss to take a more or less completed love-triangle film and edit out one of the leads, in her entirety: "you must cut out that Estella girl, every scene with her". It's a tall -- and baffling -- order, requiring the story to be reshaped into an entirely new one -- which also cuts the young actress: "out of the chance of her lifetime" --, and McCabe isn't very enthusiastic about the arduous task. But it's not just Estella Lamare's break-out role that winds up on the cutting-room floor -- so does Estella herself.

Not only does one, and then another character confess to her murder -- with a third suspect soon in the mix --, but there's already quickly some question as to whether it was even murder at all, or suicide. Whatever happened in the cutting-room was also captured on film -- a novel automatic camera set-up (complete with: "an ultra-fast developer developing in a tank which is fixed to the camera as part of it", so that the film is ready-to-watch as soon as it's removed from the camera) recorded the whole thing -- but the film was removed before the authorities got there ...... The film soon surfaces, clearing up what happened somewhat -- but it's also a cut version; it's a while before the whole film is revealed.

There's also more (and less) to Estella herself: she was: "a nonentity. She never existed, The body deceased before the spirit could manifest itself". She had reinvented herself, too: her real name was Esther Lammer, and she was from the East End; she had also been married; she had suitors.

This death is followed by another, connected one -- one that at first looks more obviously like suicide, but that is then definitively ruled out; this was definitely murder. The victim -- incontrovertibly involved in Estella's death -- had gone abroad, on the run, and yet had returned, for some reason.

The story unfolds in fairly conventional mystery-novel fashion, presented from -- and thus limited to -- McCabe's perspective. He keeps busy, and he keeps involved, with many of those around him obviously somehow involved. He has his suspicions and his thoughts -- and sometimes acts suspiciously himself, sniffing around on his own. Early on, at a night on the town, he seems to be onto something:

Then suddenly I had it.But here, for example, he declines to follow through in his account, leaving the reader guessing. He seems to be suspicious of his colleague -- as he has good reason to --, and to want to follow up on his suspicions while he can be sure the colleague won't get in his way. But author-McCabe leaves it open-ended enough that his protagonist could certainly have other things in mind .....

'Jesus Christ,' I said. 'The face on the cutting-room floor.'

Dinah rose with me.

'What's up ?'

'Sit down,' I said. 'Listen carefully. You must keep Robertson here for at least two hours. Do what you can. Talk, dance, do anything you like. Be nice to him.'

'That's simple,' she said. 'What are you doing ?'

'I'm leaving.'

'Going home ?'

'Oh, no,' I said.

Narrator McCabe isn't very respectful in his dealings with Inspector Smith -- "the big blue-eyed boy in the case. The official sleuth" --, but it's long unclear what kind of games they are playing at; indeed, both long don't seem to realize just how high their stakes are, underestimating each other in ways that sow the seeds of both their downfalls.

Events and suspicions get rehashed, repeatedly -- new light occasionally thrown on things, or simply considered from a different perspective: Müller notes in his Epilogue: "The pattern follows the plot: McCabe tells and retells the same story over and over again". Author McCabe long doesn't provide much clarity -- but while there are hints that his narrator might not be entirely reliable, there's no sense that he's just obfuscating; McCabe the narrator is seriously invested and seems concerned -- but then there's also an awful lot of (defensive ?) attitude there. And then there's that romantic streak too; this McCabe comes across (or wants to) as hardboiled -- but there's a softness hidden in there, and even as he writes about the various women he's involved with with a casual hardness, there's some weakness there, a sore spot.

Smith eventually gets around to summing up the case(s) -- and he observes that:

this isn't a detective story where things have to click. This is a thing that happened. Detective stories are puzzles -- chess played with figures that look like human beings -- but they only look human: they aren't. You must decide what you want to do -- write a detective story and make things fit fine and dandy so that your readers in Walla Walla, Tooting Broadway and Kansas City Suburb like it -- in which case you must cut out the human element and concentrate on the machinery -- or you work with more less normal human beings under more or less normal circumstances -- which is real life as it is: more or less normal and far from the perfect machinery of that fine detective story you want to make out of our case here, brother Mac.But how true to life are these characters and their actions ? With its off-key patter and unlikely quick turns (notably those volunteering their guilt as to Estella's would-be murder), The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor has all the feel of an imitation-mystery novel -- with emphasis on the imitation, especially in the rhythm, attitude, and airs of mystery. And, as such, its reasonably successful, to that point (Smith's big reveal and explanation) -- a solid B-thriller that probably is a bit frustrating to crime fiction aficionados in not quite playing by the usual rules and maybe trying a bit too hard.

But of course that's not all there is to it. After the crime is, or seems, solved, there's a trial -- and here again McCabe retells the story, or rather spins it yet another way. Smith carefully created a narrative that fully explains the crime, and hence who is responsible -- the how-dunnit -- but in the courtroom that narrative isn't so much demolished as hopelessly undermined. Smith is hoisted by his own petard.

Here too success lies in not playing by the (narrative) rules: courtroom-theater is subject to strict rules of procedure -- and the defendant knows that if he goes along with these he stands no chance. Hence he acts as his own lawyer, because no lawyer would or could take the necessary approach -- using the prosecutor's case against itself, knowing: "I couldn't build up my own case and that therefore I had to make the other one's case my own". His amateur-status -- untrained in the law -- gives him additional leeway, and he plays it to the hilt.

The trial-chapter is detailed but summary, mostly described rather than -- as much of the previous story had been -- shown played, which hammers home the point and success all the better. Its inevitable conclusion is a nice twist -- and then there's the nice concluding twist on top of it, as Smith still wants to see justice served, and the narrator accepts it (and we finally get around to learning how this account itself came to be written down).

By this point The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor has moved from fine if probably forgettable B-thriller to sharp and decidedly memorable novel. But McCabe doesn't let readers, or his story or characters, off the hook yet. There's that epitaph-epilogue .....

Here, a new narrator introduces himself, the unfortunately named A.B.C.Müller (who does begin by apologizing for his ridiculous name and initials: "They stand for Adolf Benito Comrade. Originally Comrade was Conrad. But to balance the allied powers o Adolf and Benito I felt obliged to introduce some left-wing appeal"). [The novel was published in 1937; you'd figure McCabe wouldn't have settled for quite such a crude joke a few years later.] McCabe ran into Müller a few times over the course of his story, and they've discussed this and other crimes -- including the memorable exchange:

'Looks sad,' I said. 'Cameron McCabe's dear old mother'll have to cry some buckets full of tears.'The Epilogue is ... quite a piece of work. The premise is that Müller had been entrusted with McCabe's manuscript -- now published. And while Müller maintains that: "Everything else that could possibly be of interest to the readers of Mr McCabe's book has been said by Mr McCabe himself", he adds his two cents too, offering background as to events, a lengthy consideration of the document (emphasizing: "it is the historical and social background of the characters which explains them both to the author and to the reader") as well as to the case itself -- in which, after all he played a peripheral part (and to which he can add a few facts outside McCabe's purview), and in whose aftermath he then further injects himself.

'Why ?' he asked. 'You're not mixed up in it ?'

'How do you know ?' I asked. 'I've done it.'

'Have you ?' he said.

'Looks damn much as if I had.'

'Faked evidence ?' he asked.

'Are you ?' I asked.

'Am I what ?' he asked.

'Are you faked evidence ?'

A significant amount of space is devoted to Müller's analysis of the state of detective fiction of the times and the reactions to McCabe's books, as he comments on invented reviews of it -- while also citing actual reviews and writings on crime fiction of the time. A bibliography of works quoted from cites reviews and works by L.P.Hartley, Cyril Connolly, W.H.Auden, Edmund Wilson, and Ernest Hemingway, among others, and the debate about the rules of the (literary) game is just one of the intriguing elements here -- including the claim that:

Fact and fiction are constantly fighting one another. Fairness to his characters and fairness to his readers are expected of the author. And once he claimed to have written a detective story, strictest adherence to the rules of detective fiction is demanded of him.Author McCabe, of course, pushes these to considerable extremes, in a layered novel full of teases. It's a bravura performance -- of an odd sort. There's a youthful adaucity on display here, a brash but exceptionally well-read young interloper -- Borneman was twenty-two when his McCabe-book was published, a recent émigré from Germany, new to the language -- crashing into this traditional genre. He plays post-modern games -- at a high level -- decades before they became commonplace, and if he doesn't show quite the stylish refinement of, say, modern master Gilbert Adair, there's still a surprisingly sensitive touch to his trampling of the field.

Once can see how The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor has become an admired but not quite loved novel, McCabe's mystery-story just a bit too rough and tumble and its dialogue almost too cinema-sharp (and ever so slightly off key) for genre-fans (especially of that 'Golden Age' time). For all its ambition, it's not a 'great' mystery -- but then, it's also far from simply being a mystery novel (even as it sticks, from first to the very last, to proving itself as such). There is no doubt, however, that The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor is a true classic and, even so many years later, when post-modern fiction seems to have exhausted all its tricks, sui generis and repeatedly stunning in just how far (and far afield) it goes.

A truly remarkable work of fiction. - M.A.Orthofer

http://www.complete-review.com/reviews/austria/borneman.htm

Last year, responding to some stray thoughts that brought up memories of a small number of books that I had read more than once, borrowing and re-borrowing them from Didsbury Library, but which I hadn’t read again for at least twenty years, I wrote a short series about three such. Curious as to whether I might still find them appealing, for more reason than nostalgia for the times in which I enthused over them, I hunted the books down, finding them cheaply available on eBay and Amazon, thinking to blog about the experience.

Another of those books stole back into my memory not long ago, a book easily and cheaply available on eBay, so I’m re-heading this series as Some Books, allowing me the flexibility to add to it whenever memory strikes.

The latest of these books is Cameron McCabe’s The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor.

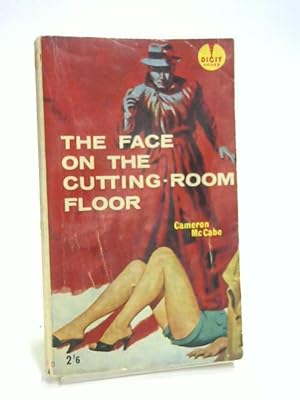

This is a very unusual book, one that was never a commercial success, but one which has retained a reputation that, despite it always being no more than a cult interest, it has been periodically rediscovered by connoisseurs. When I first read it in the Seventies, it was in its first hardback reissue after decades of obscurity, when it was extremely difficult to find.

The novel, which was McCabe’s only book, for reasons which will be entirely understandable once I go on to describe it, was originally published in 1937. When I read it, the whereabouts of the author, or if he was still living, were unknown, and its royalties were placed in a trust fund pending the uncovering of the author who, it eventually appeared was creative polymath and scientist Ernest Borneman, a refugee from Nazi Germany whose first book in English this is.

Which makes the book all the more remarkable.

I was initially attracted to this book by it’s unusual title. I don’t know if the term is still in use today, but when the book was first published, ‘the face on the cutting-room floor’ was a film industry for an actor or actress – usually a minor one – whose entire performance was cut from the finished film.

It comes into use immediately the book starts. It’s a first person narration by McCabe himself, Scottish by birth, Canadian by upbringing, a cutter (i.e., editor) working for a film company with studios near the centre of London. He’s working simultaneously on several films, including an unnamed and complete film starring Maria Ray, Ian Jensen and Estella Lamare. Ray and Jensen are established stars, Lamare a newcomer for whom this will be her breakthrough role. Until studio boss Isador Bloom orders McCabe to cut her out of the picture completely.

This is completely unexpected. The film is about a love triangle, and cutting Estella out will not only mean extensive re-shoots, but will wreck the storyline. McCabe is naturally puzzled and seeks the advice of his fellow cutter, Robertson. But first Robertson’s phone is engaged, then his studios are empty, though his camera is warm from use, and then they’re locked. So McCabe takes his secretary, Dinah, out on the town, until they bump into Robertson and other from the studio. Robertson maintains he was out whilst McCabe was trying to contact him.

Suddenly, McCabe blurts out the title, and leaves Dinah to keep Robertson out until 3.30am whilst he disappears, on business he doesn’t disclose.

The next day, the studio is filled with the news that Estella Lamare has been found dead in Robertson’s cutting rooms.

What follows is a detective story, or is it? There is a suspicious death, which may or may not be murder. There is an Inspector of Police. An amateur who becomes deeply involved in the investigation of the crime. There is another death, a person connected to the first, maybe, victim, and this certainly is a murder.

All the accoutrements are there. It walks like a detective story, it talks like a detective story, but it definitely does not quack like a detective story.

For when the killer is exposed, it is McCabe himself. But, unlike Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, exposure of the murderer is not the point of the story. We are at best only two-thirds of the way through the book.

McCabe is arrested, tried, defends himself, is acquitted by undermining Inspector Smith’s methods. A month later, Smith, disgraced, fired, turns up on McCabe’s doorstep, intent on killing McCabe for having cheated justice. McCabe, having become disillusioned at his ‘victory’, having failed to get what he (improbably) expected, admits to the killing, begs half an hour to finish his account of the affair (i.e., the book thus far), and then allows Smith to shoot him. Smith subsequently hangs for the murder.

But that’s not all. McCabe has finished by sending his manuscript to Müller, a minor character, a journalist, who has it published. Müller then writes a long, erudite, epilogue, explaining the book to us the readers, whilst simultaneously reviewing the combined efforts of the book’s reviewers, complete with extensive quotes (all taken, as correctly sourced, from real reviews, with only McCabe’s name etc. substituted for the original books).

People, what we have here is a deconstructionist book whole decades before deconstructionism was invented. Nor is that all: the ghost of McCabe pops up before the end to argue with Müller over his interpretation of McCabe’s ending.

What is yet more, now that the waters have been thoroughly muddied, Müller proceeds to throw in another bucket of silt in a short coda in which he bumps into Maria Ray, in which she contradicts all the endings so far given, and throws in several more theories (McCabe committed suicide to frame Smith as his murderer (!) is only one of them.)

Out of nowhere, Müller falls in love/lust with Maria, hopes she’ll marry him despite his age, she pulls a gun, he takes it off her and shoots her dead. Cautiously, the reader checks for more pages in which this story may perpetuate itself, but if they’ve got a new enough edition, will find only a long transcript of a 1979 interview with Borneman, about his life and career.

The Face on the Cutting Room Floor‘s fate in both obscurity and celebration may now be understandable. To call it bizarre is, in many ways, to underrate it. That it vanished so thoroughly after its early burst of popularity, based on the comprehensive flouting of every detective story convention ever accepted, is hardly a surprise. That it should be rediscovered and hailed as a classic by such authorities as Julian Symons and Frederic Raphael, is equally as predictable. When it was first re-issued, in the edition I read out of Didsbury Library, the publishers had no idea who Cameron McCabe was, nor if he still lived: royalties were paid into a trust fund.

The book itself is unfathomable. I know that I read it twice, once out of curiosity at the title, and a second time for reasons I can no longer recall but which were probably based to some extent in the sheer difference between this book and anything else I’d discovered in exploring a goodish-sized suburban Library. Whether I actually liked it or not is something lost to time and memory. I certainly don’t in 2015.

And this is in the main a response to tone and voice, much more than to a plot that is deliberately confusing, told by an extremely unreliable narrator. I’ll come back to that shortly, but first let’s admit that Borneman, as Müller, does a very good, very accurate job of anatomising Borneman as McCabe.

The story progresses up to Chapter 19 in a fairly brisk, lineal fashion, though with very significant gaps, which are alluded to in a manner sufficiently casual as to not draw attention to the fact that McCabe is not telling all that is happening. An alert reader would also begin to question in what manner McCabe gains large chunks of knowledge that seem to materialise out of the ether.

But from Chapter 20 onwards, the whole plot is recapitulated in every chapter, over and again, in different words, sometimes with new information revealed, most notably McCabe’s accusation and arrest. At the heart of it is a love story: more than one. Estella was having an affair with Ian Jensen, until he threw her over for Maria Ray, Bloom wanted her cut out because she refused his advances. McCabe was in love with and having an affair with Maria Ray until Jensen came between them.

Estella threatened suicide unless Jensen came back to her. Jensen tried to take the knife off her but her wrist still got cut. McCabe found the film of this, edited it to look like murder and blackmailed Jensen into leaving England. When he returned, McCabe poisoned and shot him. But (and this comes as a total surprise to him after he slanders her as promiscuous in defending himself, Maria won’t come back to him, which is why he’s willing to let Smith off him.

But Cameron McCabe is simply a deeply unpleasant person to be around. He’s the kind of guy who knows himself to be infinitely smarter than everyone else around him. He has an opinion on everyone and everything and all of it is nothing more than an unpleasant stink beneath his nostrils. He’s the kind of guy who will sleep with a woman with whom he’s besotted and despise her for having sex out of marriage.

And he’s so fuckingly, grindingly self-important, with his perpetual dispensing of opinions, his utter conviction that he and only he truly understands, his barely repressed loathing for the rest of humanity. He talks in a semi-American film dialect, a never-ending slang that gets old long before the book does, judging and condemning and generally coming over as a complete pain-in-the-arse. In fact, he reminds me of this guy on one of the fora I use…

As for Herr Müller with the two dots above the u, he is no better in his own way. His Epitaph is yet another demonstration by someone being conspicuously clever, one-upping McCabe by showing off his erudition, with his ‘enhancing’ of McCabe until the latter pops up for one final even-smarter-than-you session.

It made for heavy going reading and an overall impression of the author as smartarse showing off. Though as a German refugee writing in an English he was still in the process of learning, it has to be allowed that Ernest Borneman was indeed very clever, as his subsequent career showed.

Nevertheless, it doesn’t make for a book to be retained for further reading. At least I shalln’t be tempted by faltering memory to give this one a further try-out in 2035, should I live so long. - Martin Crookall

mbc1955.wordpress.com/2015/10/13/some-books-cameron-mccabes-the-face-on-the-cutting-room-floor/

Why it’s been 30 years since the last reprint of The Face On The Cutting-Room Floor is a mystery as perplexing as anything in the book itself. A post-modernist crime thriller which deconstructs crime thrillers, from an author whose identity remained unknown for 37 years after its publication – what could be more deserving of cult status than that?

It originally came out in 1937, and while many of its innovations may have been adopted by mainstream literary fiction it’s lost none of its power to fascinate and bemuse. Central character Cameron McCabe, who purports to be the author, works as an editor in a London film studio. A headstrong man in his late twenties, he’s fuming over his boss’s order to cut every scene featuring young starlet Estella Lamare from the film he’s working on – which, since it’s about a love triangle, completely alters the story. Later the same day, Estella is found dead in another part of the studio. It looks like suicide, but the fact that a reel of film which may have recorded her death is missing throws a more suspicious light on her demise.

McCabe makes up his mind to get to the bottom of it, and when Inspector Smith from Scotland Yard arrives the two immediately clash.

But although the author obviously loves detective fiction, he fiendishly subverts it. Where we’d expect the plot to move forward, we’re instead presented with recaps, albeit all slightly different from each other. Then comes the final section: a long afterword written by one of the characters, which evaluates McCabe’s story in terms of its (fake) critical reception, its place in the detective genre and its context of a modern culture which is “a sordid arena in which even the winner takes nothing”.

Eight decades on, it’s still a hugely impressive conceptual labyrinth, retaining much of the originality it would have had for its initial readers. Especially when you consider – and this isn’t giving away anything that would spoil it – that its author was Ernst Bornemann, a German emigré who was only 19, had been unable to speak English only four years earlier and had written it to test his command of his new language. - Alastair Mabbott

https://www.heraldscotland.com/arts_ents/14762426.post-modernist-crime-thriller-deserves-cult-status-the-face-on-the-cutting-room-floor-bycameron-mccabe/

When I was thinking up ways of promoting my new book, Literary Stalker, I toyed with the word ‘metacrime’ – a compression of ‘metafictional crime’ – and I did a search to see how widely the term had been used before, and in relation to what. I discovered it was hardly in use at all, and the only work I came across that bore that particular label was the 1937 ‘Golden Age of Crime’ novel The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor by Cameron McCabe.

The search led me to an excellent review of the book by Ted Gioia, which is posted on a site Ted has dedicated exclusively to the phenomenon of Postmodern Mystery, also dissecting works by Borges, Nabakov, Flann O’Brien, Paul Auster and other writers familiar to me – I had never heard of Cameron McCabe. Further trawling revealed that at least three of my writer friends – Nicholas Royle, Andrew Hook and Christopher Fowler – had written about this mysterious man and his novel, so he was not perhaps as arcane as I’d thought, and I needed to discover more.

I expected to have to make do with a dog-eared and dubiously stained version of the tome, disingenuously described by the seller as in ‘very good condition’; but no, a new version has fairly recently been published by Picador Classics, coming with an introduction from Jonathan Coe and so many bits of front and back matter that it’s hard to know where Cameron McCabe’s own input ends and that of others begins – which is precisely what the novel is all about.

Coe’s introduction sets out the parameters and of course the name ‘Cameron McCabe’ is just a device – both a nom de plume and the protagonist/extremely unreliable narrator of the tale. Keeping the synopsis side of things simple, the plot involves the ‘murder’ of actress Estella Lamare, to which several characters confess, but which later, by means of hidden camera footage, is shown to be a suicide…maybe. But soon another ‘real’ murder takes place, and things resolve into a Crime and Punishment-like duel between McCabe, as witness and later suspect, and Inspector Smith, the sleuth on the case. Presently another important character, A. B. C. Müller, enters the stage, and everything is set for the most meta of meta-mysteries you could ever hope to find.A strong early feature of this meta dimension is the retelling of the events surrounding the murder many times over, subtly changing and embellishing the content with each cycle. This has both the effect of a witness’s statement mutating under pressure and a writer’s ongoing experiments with narrative layering. The repetition is tedious at points, but we see where ‘McCabe’ is going, so interest is retained. Progressively the convoluting mystery resolves into the stories told about it, so it becomes not just a question of which character’s version we believe, but which ‘storyteller’s’ version we believe also. In other words, ‘true facts’ are blurred in a delirious metafictional merry-go-round.

The rug is further pulled out when Müller steps in and engages in a deconstruction of everything that has gone before, quoting ‘reviews’ of McCabe’s work and musing on the crime genre in general. Eventually the metafictional spiralling becomes playfully absurdist in the manner of later practitioners of the art, such as Thomas Pynchon, John Fowles, Richard Brautigan and Kurt Vonnegut – and I found it hard to believe this novel was actually written and published before World War II!

And that is the really remarkable thing about The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor – it’s so far ahead of its time. In an appended interview with the real author of the text – Ernest Borneman – he says that as a 1930s Berliner he and his friends were into Joyce and Proust when others were still raving about Galsworthy and Yeats. But there are few clues as to how Borneman made the leap to an almost 1960s-flavoured postmodernism so deftly. One tends to think of Borges as the main pioneer of metafiction, with his early stories written over roughly the same period as The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor. Out of the tradition of Borges, and later Nabokov and Pale Fire, the ’60s metafiction movement took shape, alongside post-structuralism, deconstruction and so forth. But developments are never that straightforward, and it must be remembered that Flann O’Brien’s pioneering At Swim Two-Birds was also written in the 1930s.

Yet when I look at Patricia Waugh’s Metafiction (published in 1984 and my principle introduction to the subject back then), O’Brien along with Borges, Nabokov, Barthes, Pynchon, Fowles, Brautigan, Vonnegut, Lessing, Robbe-Grillet and many others have their contributions recognised; but there’s not a word about ‘Cameron McCabe’, because he was well and truly forgotten – or ‘unrediscovered’ – back then. As the appendages to the new edition of The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor make clear, it was detective-story aficionados Julian Symons and Frederic Raphael who started its rehabilitation, yet its importance within the postmodernist cannon is equally manifest.

Which brings me back to ‘metacrime’, which should become more recognised as a genre, in my opinion – the sumptuous fusion of crime, thriller and indeed horror elements with postmodern trickiness. But of course I’m biased, as I’ve just written a metacrime novel myself, and though I discovered The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor after I’d completed Literary Stalker, the parallels and simpatico feelings are still strong.

There’s the idea that once a crime plot is being written about within the text, the complications increase by geometrically higher powers and ‘plot thickening’ takes on whole new connotations. Then there’s the detective as larger-than-life sometimes deliberately parodic creation, a vortex of irony within the text – McCabe had Inspector Smith and I’ve got Inspector Leopard (a name deliberately borrowed from a Monty Python sketch). And alongside this lies the tendency to comment upon and analyse the crime genre as a whole. Finally there’s that layered artful ambivalence of the real and the fictional – or the fictional real and the fictional fictional – which must be taken far enough to count for something but not so far that it brings the whole suspension-of-disbelief house of cards down. Metacrime is a tricky high-wire act, but it’s definitely the genre of tomorrow! - The Mad Artist

https://musingsofthemadartist.wordpress.com/2017/12/21/metacrime-murder-mystery-the-face-on-the-cutting-room-floor-by-cameron-mccabe/

I saw the ships in the water and the lights of the stars in the water and the reflections under the bridges. The pubs were about to close and when the doors opened there were waves of smell and light and sound floating out into the fog. There was laundry hung up on lines across the darkness in back yards. In the small streets there were lighted windows and one was open and you could see the warmth from inside passing out into the mist and there were whirls of smoke and fog in the light and a girl sang ‘When your lover has gone’ and her voice was low and husky from too much smoking.

This is the narrator, Cameron McCabe, in typically reflective mood on a visit to Chinatown in London’s East End. McCabe is a strange mixture of hard-boiled cynicism and an extreme sensitivity to external phenomena. He is a film editor, working on a feature film in a London studio and, as the books starts, he has been ordered to cut a young actress, Estella Lamarre, out of the film completely – she will become what’s known as ‘the face on the cutting-room floor’. McCabe objects – the film concerns a love triangle and will make little sense if one of the participants is cut out. Soon, though, this all becomes more or less irrelevant as Estella is discovered dead, having been stabbed in a cutting-room at the studio. This room turns out to have a special camera installed, which starts recording when someone enters the room. Thus it becomes possible to see the actual stabbing of Estella, in which her lover Jensen is involved, though it’s far from clear whether this was murder or an accident. Then Jensen disappears, only to be rediscovered a few days later, having been murdered in a shabby London boarding house.

Now begins a most bizarre investigation and, eventually, a trial. Several people confess to the murder/s, but the ineffectual detective Smith is certain that McCabe is responsible and manages eventually to get him arrested. McCabe chooses to represent himself, and does so with the aid of two famous law books, which he cites many times in his own defence. His character is pretty well assassinated during the trial, largely by the revelation that, though in love with the actress Maria Ray (whose credibilty, however, he doesn’t hesitate to question, citing her promiscuity as a reason), he has been carrying on a simultaneous affair with his secretary Dinah Lee. He manages to impress the jury and gets acquitted, but Smith has not finished with him…

So much for the plot, which is curious in itself, twisting and turning but never really moving forward very much, being more concerned with different peoples’ views of the same event. But that is far from the most curious thing about this novel. First published in 1937, it continues on past the end of the narrative with a section entitled ‘An Epilogue by A.B.C. Müller as Epitaph for Cameron McCabe’, in which the supposed Müller, apparently a literary critic, undertakes to defend the novel from various supposed criticisms and compares it favourably with the work of writers such as James Joyce, Hemingway and Dasheil Hammett. He speaks of McCabe in disparaging terms (‘the arrested development of the criminal mind’) and reveals a fact about his recent death that he says he heard first hand from Maria Ray herself.

When the novel was first published, it was assumed that McCabe really existed, and after its success the publishers placed advertisments asking his heirs to get in touch with them. Following a reprint in 1974, however, a reviewer revealed that he had discovered the real identity of the author, one Ernst Bornemann, who, as further research revealed, was an eminent author and sexologist living in Austria, having anglicised his name to Ernest Borneman. The Face on the Cutting Room floor had been written when he was only 19, and he had started learning English some four months earlier.

All this undoubtedly makes the novel a post-modern literary curiosity, but is it more than that? I would say a resounding yes. True, the main plot is complex and in fact doesn’t make much progress, but, despite or maybe because of Borneman’s new acquisiton of English, the language is wonderfully evocative in the hard-boiled mode so beloved of American novelists of the era. McCabe’s observations of the world around him – the winter London weather with its swirling brown fogs and the November sky, ‘orange and heavy’ – and his cynical analysis of the motives and morals of his circle and indeed of himself, make the novel a real pleasure to read. And of course the setting – the busy, up-to-date film studio, the grimy London streets – and the louche, amoral characters who inhabit it – is a fascinating and informative. In addition, a whole essay could be written on the Epilogue, in which the supposed Muller quotes page after page from what are apparently reviews of an earlier (non-existent) edition, which are actually altered versions of reviews of a number of other, genuinely published, works.

The Picador Classics edition I read has an interesting and informative introduction by Jonathan Coe and an afterword containing extracts from a 1979 interview with Borneman. Great stuff! - Harriet

shinynewbooks.co.uk/shiny-new-books-archive/issue-12-archive/reprints-issue-12/the-face-on-the-cutting-room-floor-by-cameron-mccabe/

Prior to reading this book, I knew it was one which is famous for its genre bending, rule breaking and unconventionality. In that respect it did live up to expectation. The Face on the Cutting Room Floor (1937) begins with the overweight and pastry loving film producer Isador Bloom, asking the Chief Cutter Cameron McCabe (author and narrator of the story), with the aid of special effects expert John Robertson to remove all of Estella Lamare’s parts from the film The Waning Moon. Bloom gives no reason for this drastic and costly decision and McCabe is not happy with it. After all taking the second female character out of a love triangle focused film does seem inexplicable. Regardless of his own opinions McCabe goes off in search of Robertson but unluckily manages to miss him, though an engaged tone on Robertson’s office phone and a recently used camera suggests he was there. Giving it up as a hopeless task, McCabe goes out for the night with his secretary Dinah Lee, though this ends unhappily at a nightclub, as McCabe sees the actress Maria Ray out with another actor, Ian Jensen, which brings his now unrequited love to the surface. Robertson also makes an appearance at the nightclub intimating that he left his offices several hours before McCabe went looking for him. This information has a significant effect on McCabe who rushes off into the night…

The following morning Estella is found dead in Robertson’s office, with wounds to her wrists. Was it suicide or a murder? Murder definitely seems the more likely option as not only is the film missing out of the camera (which Robertson left on as part of an experiment), both Bloom and another man confess to killing her. Are they telling the truth? Or if not why are they lying? Detective Inspector Smith is called in to solve the case, with McCabe seemingly taking on a form of amateur sleuthing, revealing much more startling information about the case such as finding the missing film and discovering that Maria fears Jensen being the murderer. But unsurprisingly the showing of this film creates more questions than answers and a further death also complicates the situation. Again with this death there is a question mark as to whether this was a suicide or a murder.As the investigation continues Smith and McCabe have an increasingly tense relationship, as McCabe’s role blurs and merges with others. When the case finally goes to trial notions of truth, causality and legal principles are undermined, called into question and essentially just turned inside out. Although many of the characters talk at times in a trifling manner, (making Lord Peter Wimsey’s conversational manner seem normal in comparison), this is no light hearted crime novel and the ending of the novel proper is a dark one, problematizing the issue of justice. What follows this is a metafictional epilogue, written by another character which critiques what has passed already, where the detective fiction genre is overtly turned on its head – although within this section further twists are to come…

My Thoughts

From what I have written this story doesn’t seem that bad, some may even say quite clever or quirky and maybe it is, but it is also very very very very very very BORING! I said it. Boring. The descriptors, confusing and complete nonsense would also be applicable. My problems began quite early on as the narrative cuts or jumps around a lot. This may well be an attempt to mirror film narration but in a novel it lacked continuity. Moreover there were many points in the novel where the plot made little sense, with McCabe talking in nonsensical riddles or talking with other characters in such a dialect that I had no idea what they were actually saying. The epilogue compounded these issues attempting to sound literarily clever and philosophical but was actually just convoluted nonsense which made no sense and dragged on for page after page. Consequently when the unconventional aspects happened they were rather spoilt as either my brain was so painfully numbed by the rest of the text that I couldn’t care less or the rule breaking, genre bending parts were over used. For example in the epilogue I hint there are twists to follow and I do mean in the plural, you could say there was an excess of them. But for me this parodying was overdone and therefore pointless and unsatisfying. Though to be fair I think the whole novel could have done with being shortened.

Additionally I also found McCabe to be a hugely unlikeable unenjoyable character, which is difficult when they are the narrator. Though again, like with the aspects of the novel which turn genre rules upside down (something I usually enjoy), I think I could have appreciated or coped with McCabe’s character more easily, if the narrative style itself was not so long winded or nonsensical. I’m not kidding you can easily read a whole dialogue or a paragraph and have no idea what it was about. Moreover, the pacing in this novel was completely off, often being too slow, especially in the epilogue where I did contemplate hitting my head off the book (or even a wall) it was that painful to read. I was very close to quitting.

To be fair to the story and the writer it is a very clever book and actually had the basis for a very good film themed plot. However something I have learnt from reading this, is that a story may be exceptionally clever, but this does not matter or cannot be appreciated if the actual story is told in a poor way and if the actual reading of it is unenjoyable. Reading through pages of nonsense in this book was not made up for by its cleverness. So unsurprisingly I am not recommending this book to anyone unless you are a glutton for punishment or are keen to read an author who is not very well known. -

crossexaminingcrime.wordpress.com/2016/04/08/the-face-on-the-cutting-room-floor-1937-by-cameron-mccabe/

Ted Gioia’s essay on Postmodern MysteryNicholas Royle on The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor

Though The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor was first published in 1937, the true identity of its author remained a mystery until 1974 when it was discovered that the well-known German sexologist, jazz musician and critic Ernest Borneman was "Cameron McCabe." Borneman died in 1995.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.