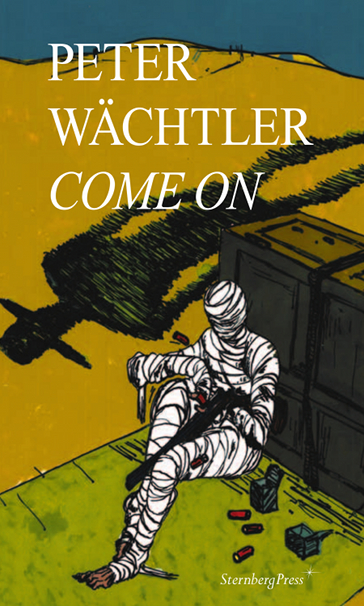

Peter Wächtler, Come On, Ed. by John

Kelsey,

Jakob Schillinger, Sternberg Press, 2013.

Passivity and contemplation characterize the narrators of Peter Wächtler’s stories. Some speak from the vantage point of death, musing about their lives, recalling formative experiences and decisive moments. Those still alive seem paralyzed—functioning or malfunctioning within their world, but unable to act upon it. At a moment when narrating experiences seems more important than having them, and when such narrating takes on increasingly standardized forms, Wächtler’s writing foregrounds different narrative techniques and traditions as means of rationalizing one’s place in the world, of grappling with and giving meaning to one’s existence. Unlike the various fatalist and voluntarist doctrines which these stories mime, the social totality here creeps into the picture. Fate turns into slapstick and only as such conveys the horror of life in an administered world. Hollowed-out phrases from the repertoire of communication agencies and shallow love songs are made to speak beautifully of a world that is not—and critical theory proves as potent a means for territorial fights as fists or a kryptonite bicycle lock.

Come On is a MINI/Goethe-Institut Curatorial Residencies Ludlow 38 publication in collaboration with Reena Spaulings Fine Art. It compiles ten texts by Peter Wächtler written between 2011 and 2013.

While Wächtler, who was born in 1979, works in a range of media,

including drawing and ceramics as well as animated films and short

fiction, his practice is narrative at its core. The objects he

produces and his works on paper often seem like snapshots from his

short stories, portraying similar personnel in analogous

constellations, settings, and scenes. The humanoid animals

predominant in Wächtler’s sculptures—for instance, an ensemble

of three laboring mammals and one bird (Untitled, 2013), situated

somewhere between The Burghers of Calais and the Town Musicians of

Bremen, or oversize crabs confronting more agile creatures of the sea

(Untitled, 2014)—find their complement in the stories’

animalistic humans. After the loss of his girlfriend, Peter, the

protagonist of the story “At the Wiels” (2012), acquires a

lobster to satisfy his “deep need of a true friend,” while his

rival, Ragnar Pluto, not only shares his surname with a cartoon dog

but also has “huge and shiny ivories, which were last seen during

the war against the mammoth led by long extinct predators”; a

“horse-like penis”; and a similarly equine mane.1 The narrator’s

friend in “Come On”(2014), called “the Pig,” grunts instead

of speaking and is eventually slaughtered.2 There are correspondences

between narrative and object on the structural level, too. For

example, the Janus-headed sculpture Untitled, 2014, juxtaposes

lethargy and enthusiastic activity (or fiesta and siesta, to drive

home the linguistic dimension of the sculptural pun) in a single

being—a configuration found in many of the stories. Most important,

the technological and aesthetic outmodedness that marks Wächtler’s

drawings and sculptures resonates with his time-based work’s

emphasis on the literary—at a moment when art discourse is largely

defined by concerns that seem to belong to another cultural paradigm

altogether: an obsession with anything remotely “post-Internet,”

a fascination with the decline of subjectivity and the

ever-accelerating rhythm of feedback and affect under a cybernetic

regime, and an impulse to historicize the “Anthro-pocene” and the

human as such.

TRACING THE INTIMATE

historical connection between literature and humanism, philosopher

Peter Sloterdijk, at the dawn of the Internet age, used the term

postliterary to designate a fundamental restructuring of culture. He

was quick to point out that “of course, that does not mean that

literature has come to an end, but it has split itself off and become

a sui generis subculture, and the days of its value as bearer of the

national spirit have passed. The social synthesis is no longer—and

is no longer seen to be—primarily a matter of books and letters.

New means of political-cultural telecommunication have come into

prominence.”3 Following Sloterdijk’s diagnosis, we might say that

the untimeliness of the literary—the medium most associated with

representing, transmitting, or producing subjectivity—pervades the

whole of Wächtler’s practice. It is, however, not a literary

practice. Rather, it could be seen as a postliterary investigation of

media, production, subjecthood, and objecthood at the current

moment—an enterprise that produces alternately comical and

heart-wrenching effects.

First-person

narrators take center stage in Wächtler’s stories, but rarely have

much diegetic function. They passively contemplate their surroundings

and, most of all, their own lives, recalling decisive moments,

formative experiences, traumas. Many speak from beyond the grave, and

even those still alive are paralyzed—functioning or malfunctioning

within their world, but unable to act. The protagonists of a trilogy

of animated films—Untitled, Untitled (Heat Up the Nickel), and

Untitled (Crutches), all 2013—illustrate this condition starkly:

Each is trapped inside a loop. While repetition of modular visual

elements has always been central to the economy of animation, this

labor-reducing device is typically meant to go unnoticed. But in

Wächtler’s trilogy, the characters loop ad nauseam. Exhaustion is

inscribed in their postures and movements as they enact typical

cartoon routines, such as trudging across the screen on crutches or

dragging themselves to bed only to stumble, fall, and get hit on the

head by a bowling ball conveniently positioned nearby. They toss and

turn, or sleeplessly sit on a makeshift cot by a flickering campfire,

as fragmented narratives unfold via voice-overs or subtitles whose

repetitious structures reiterate the sense of involution. The rat

starring in Untitled recounts memories ranging from the banal to the

surreal, conjuring moments of beauty or humiliation or pain,

commencing each anecdote with the same words: “How I decorated my

apartment and invited my new friends over who made me almost

immediately feel like shit in every respect . . . How I lost my

virginity on a stinking ferry to England . . . How a super-aggressive

big white worm pops out of your left eye, while we are eating Asian

noodles after a long day at work . . .” - Jakob Schillinger

Peter Wächtler’s work alternates between many different

(narrative) forms to talk about everyday occurrences as well as his

own experiences and observations, which he mixes with cartoons and

references from pop culture, film and art history. Many of his works

are witty and playful, and his figures are repeatedly caught up in a

tragicomedy. His visual world often plays with language, and writing

functions as a way to connect the different aspects to this practice.

In a simple, but strong language, interspersed with small mistakes

taken from the German syntax, one reads and hears Wächtler's

semi-fictional prose poetry, describing memories, anecdotes, absurd

situations. The exhibition spaces, the installation of the video

works in the space in combination with other elements of his artistic

work, also play an important role. Objects, sculptures and drawings

sometimes reach from the projection screen into space, expanding the

experience of his pictorial world and reality. What role does the

surrounding space play in Wächtler's work, and what possibilities

does it offer?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.