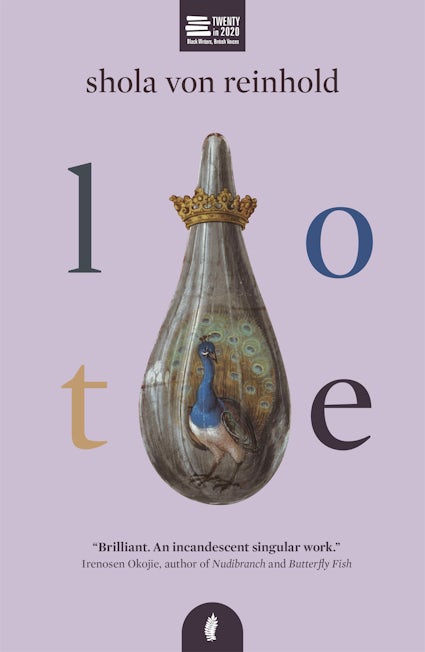

Shola von Reinhold, Lote, Jacaranda, 2020.

A literary novel which follows present-day narrator Mathilda's fixation with the forgotten black Scottish modernist poet, Hermia Drumm, LOTE is an exploration of aesthetics, Beauty, and the ephemeral realm in which they exist.

Lush and frothy, incisive and witty, Shola von Reinhold’s decadent queer literary debut immerses readers in the pursuit of aesthetics and beauty, while interrogating the removal and obscurement of Black figures from history.

Solitary Mathilda has long been enamored with the ‘Bright Young Things’ of the 20s, and throughout her life, her attempts at reinvention have mirrored their extravagance and artfulness. After discovering a photograph of the forgotten Black modernist poet Hermia Druitt, who ran in the same circles as the Bright Young Things that she adores, Mathilda becomes transfixed and resolves to learn as much as she can about the mysterious figure. Her search brings her to a peculiar artists’ residency in Dun, a small European town Hermia was known to have lived in during the 30s. The artists’ residency throws her deeper into a lattice of secrets and secret societies that takes hold of her aesthetic imagination, but will she be able to break the thrall of her Transfixions?

From champagne theft and Black Modernisms, to art sabotage, alchemy and lotus-eating proto-luxury communist cults, Mathilda’s journey through modes of aesthetic expression guides her to truth and the convoluted ways it is made and obscured.

To read Shola von Reinhold’s ornate, multi-layered novel LOTE (2020) is to encounter a baroque mind. It tells the story of a queer Black thinker named Mathilda, in the present day, who is transfixed by an historical era that does not adequately represent her. Via diaries, letters and photographs she discovers the Bright Young Things, as they were fondly known, a set of decadent and disobedient socialites who threw elaborate, drug-fuelled parties across the 1920s and 30s. Through a cocktail of hedonism, androgyny and queer love, this group — along with their counterparts in the Bloomsbury Group — began to deconstruct patriarchy a century ago, and seem to offer Mathilda an escape from the present, with all its social and racial barriers – except they don’t. The catch is that members of both groups were, by and large, spoilt, white and rich. Despite their experimental poetry, queer lifestyles, and self-fashioning (‘frock consciousness’, as Virginia Woolf called it), radicality is countered by entitlement; after all, rich people have always made exceptions of their own kind.

The novel is underpinned by a question: Why are so few queer Black British modernists documented in those flourishing interwar years? Through an impressive mix of scholarship and historical fiction, Reinhold sets out to unravel and challenge this history, prying open the ledgers to ask how and why the received archive is so overwhelmingly white. ‘I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman,’ Woolf famously wrote. ‘And/or Black,’ amends Reinhold – and with this as a sort of epigraph, their novel begins both a critique and a celebration of the era, setting out to recover the lives of Black Anons, and to conjure voices that didn’t make it into history.

The novel opens in the National Portrait Gallery archive in London, circa 2019. Mathilda has been recruited, without pay, to sift through a donation of photographs. Not yet captioned, these snapshots have been gathering dust in the gallery for a decade, their significance undetermined. Mathilda is a self-declared ‘Arcadian‘, her term for a pleasure-seeking yet political archivist, who strives to enhance her present with visions of the decadent past. She takes an almost narcotic delight in glimpses of the Bright Young Things, particularly the ‘brightest’ member, as he was once christened, the muse Stephen Tennant. Those neglected photographs turn out to be scenes of ‘modernist Alpine Queerdom’: exquisite, if familiar, images of the Bright Young Things jetting off on a skiing holiday (one particular jewel captures Tennant hand-in-hand with his lover, the war poet Siegfried Sassoon). But then Mathilda comes across an image unlike one she’s ever seen before: a costume party held at Lady Ottoline Morrell’s Garsington Manor, where her beloved Tennant appears beside two women bedecked as Renaissance angels. One flaunts a pair of feathered wings and a fine chain mail suit, grasping a champagne coupe – and her skin is black. Her afro doubles as a kind of halo, ‘brushed into a commanding nimbus’, enthuses a mesmerised Mathilda. ‘It made me ache with jealousy and bliss.’ Entranced, she steals the photograph, determined to learn more about this Black pleasure-seeker – and thus the book slips into gear. Who is this Black Bright Young Thing, and why is she absent from the history books? As Mathilda will discover, she is a Black Anon who exists only in fragments – appearing in scraps of gossip (often defamatory), and cited in sources that can’t be tracked down. When invoked by her contemporaries, she is exasperatingly anonymised as ‘the Mulatto paintress’ or ‘the Negress of Dun’. A disembodied figure, she turns out to be a lost Modernist poet, whom the prejudices of her day, combined with the bigotry of successive archivists, have vanished from the archive.

Hermia Druitt – whose life Mathilda comes to uncover – is an invention of Reinhold. They insert Druitt into actual history in order to show how she really might have existed, in turn allowing her to stand in for other Black Anons who have been irretrievably lost to the present. When it comes to representing non-elite, non-white lives, the historian’s hands are often tied by the absence of primary sources – letters, diaries, artworks – a reflection of who gets to write, and what sources are deemed worthy of the archivist’s attention. Reinhold does what a historian could not, inventing a figure – a Scottish-born Black poet of ‘Low Bloomsbury’, a queer woman and friend of Tennant, a guest at Garsington, a minor figure who should have been a major one, had the world not been so snobbish, cruel, and often racist.

Partway into the novel, Mathilda orders a cocktail called a Poussé Cafe Royal, one popular with her heroes, which ‘came served in a tulip glass and consisted of a rainbow of alcohols floating on top on one another’. In a way this image encapsulates the novel itself, which plays out on many levels, and in many sources, all at once. To sip the novel’s prose is to be whisked away on a fractal journey, in which the author transfigures into an eclectic ensemble of voices, shape-shifting through different forms and styles. First there is Matilda’s narrative in the present, in which she travels to Europe on a quest to locate Druitt’s missing poem. At the same time, stratified into the book are chapters of an invented academic text, Black Modernisms – missing from libraries, but which Mathilda hunts down – in whose pages a professor named Helen Morgan follows on Druitt’s trail a decade earlier. Finally there is Druitt’s own story, inserted into the novel by Reinhold, and encountered in invented primary sources: letters written by friends, and fragments of Druitt’s own memoir.

The strategy of writing Druitt into the archive is a form of historical revisionism. In his clever novel Confessions of the Fox (2018), Jordy Rosenberg deployed the same tactic to address the unsatisfying, and often violent, representation of trans people in the archive, who are encountered though documents that sexualise, medicalise or make monstrous. LOTE adds to this emerging revisionist literature. Cocooned within Mathilda’s narrative are alternatives to actual history, hatched by way of radical scholarship, as Reinhold utilises sources that obscured, and stole from, the Black world, and plunders the archive back.

Mathilda’s first-person narrative is written with intoxicating beauty, co-opting the highfalutin party-prose of the Bright Young Things as she emulates Druitt – describing the present as her hero might have done – to report on ‘gowns the colour of algae’, ‘a bowl of amethyst punch’, ‘a wheat coloured wig’. Meanwhile, Reinhold’s scholarship, distributed across the novel as chapters of Black Modernisms, sets out some of the harsh historical realities. If, writing from the present, Mathilda tends to indulge and rose-tint the era, as Morgan, Reinhold brings Druitt to earth.

LOTE is a novel about coming to terms with one’s heroes, as its author – via Mathilda and Morgan – grapples with both the possibilities and failures of queer British literary history. How receptive were the Bright Young Things and ‘the Bloomsberries’, as they are affectionally called, to friendship across the so-called colour line? Through Morgan’s scholarship, which Mathilda devours, Reinhold is able to explore the the spectrum of possibility, to rub up against, and expose, the era’s limits. As a queer woman, a poet and aesthete, Druitt would no doubt have sought out the group, but who would her allies have been? In the 1920s and 30s, there really was a queer intersection between the Harlem Renaissance and the Bright Young Things: the so-called ‘Faggot’s Ball‘ in Harlem in 1929 attended by the British; in turn, queer Black Harlemites like Richard Bruce Nugent – whose unpublished 1920s novella Geisha Man Reinhold cites as an influence – visited London. What’s more, members from both sets sojourned in Paris, where the Négritude movement and relaxed attitudes to homosexuality worked in everybody’s favour.

Instances of intellectual fellowship can also be pinpointed: as Black Modernisms recounts, the British eccentric Edith Sitwell formed a friendship with Trinidadian historian C.L.R. James; Garsington hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell befriended the singer Josephine Baker. Central to the plausibility of Druitt’s story is the American shipping heiress Nancy Cunard, herself a writer who established a Modernist publishing house in the 1920s. Reinhold identifies Cunard as an available historical figure through her intellectual and romantic union with the Black jazz musician Henry Crowder, which caused outrage among Americans at the time (Cunard was disowned and disinherited). Together Cunard and Crowder published a number of canonical African-American writers in the 1930s through the Hours Press, among them Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. This fact of history gives Reinhold room for more: in their historical insertion, Druitt’s lost poem was published by Hours, but subsequently vanished – perhaps intentionally suppressed. - Izabella Scott

Interview with Shola von Reinhold: ‘It felt like Hermia Fabulated herself out of the archive’

1ST JUNE 2021 by FRANKIE DYTOR

On zoom between Glasgow and Hamburg, Shola and I sat down to discuss LOTE, the novel which inspired my new series, BAROQUE. We talked about hyper-aesthetics, trans joy, and mourning in the archive. Thank you, Shola, for your time, grace and intellectual generosity throughout the interview!

As I was reading LOTE, I felt sensorially overwhelmed – it was this really heightened experience and I was wondering, if I felt that reading the novel, what was the process of writing it like?

I think it would be a lie to say anything other than that writing fiction is generally a sensory process for me and LOTE was no different. I guess how I write does issue from a sensorial place and it happens very visually. Apparently this visuality isn’t universal: I was watching an interview with Susan Sontag, who was talking about how, when she writes, she hears the words rather than sees images. That said, for me the visual means less the information side of things, and more something which is loaded with various registers of the optical – the haptic eye, the sensory eye and so on. Which has been reminding me of Tina Campt’s Listening to Images (2017) and I love the fact of these other layers of the senses – in this case, she is looking at the photographs, but she is listening-looking.

That’s so interesting, because that really reminds me of how across your work, so much of your writing takes up typically Decadent themes like the deliberate blurring of the senses, a focus on artifice but also attention to sensuality and material texture. Did you deliberately play with this in your work?

LOTE was probably less directly influenced by fin de siècle ‘Decadence’ than some people seem to think; but my curiosity with and love of certain modes and forms and ways of being that have a considerable stake in the aesthetic world do mean I end up thinking about all those typically Decadent methods you mention – but they’re (usually) not there to make it ‘Decadent’ or even just ‘decadent’. That given, I do also have more of a general interest in decadence. Both the particular movements associated with the word and other connotations of decadence including the way it’s used in art history, not to mention the way Marx uses decay to describe the stage of an economic epoch. Separate from (but overlapping) the French instantiation, it has that particular association with Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde and the decadent project stemming from Wilde-era aestheticism. The word is often used to describe anything that is deemed stylized. To go back to Sontag – and it’s weird to think how her work in the 60s is closer to the ‘belated’ decadents of the 20s than it is to us now – as well sculpting out, critically, the category of camp, she speaks of camp in another essay in terms of ‘stylization’, of which decadent work was a prime example. So there’s that as one taste category, which is cognate with the decadent. And then there are other terms like the pastoral (used in a specific sense of the word relating to the poetic convention that formally and thematically dissented from the Epic) to describe writers like Ronald Firbank. Then there are terms like baroque and rococo which, like decadent, are used in a more general sense to describe a type of art or period of art history that is stylistically involved. All of these modes share an attendant constellation: artifice, surface, ornament, beauty, excess, pleasure and so on. Subjects which resonate for me. And I usually (in my head) branch all these modes under the ‘extra-aesthetic’, the ‘extra’ obviously being completely relative – it’s always worth asking when statements like ‘over the top’ are made: over the top of what? Over the top of who: whose bland imposition? Even as more space has been sculpted out in recent years for the extra-aesthetic (in certain quarters) and the kinds of art held aloft have changed (in certain quarters), this regulation and relegation of the decorative and opulent visions persists, whether it is invisibility, simplicity, or unobtrusiveness being championed, or add to that stylelessness, harmony, evenness, order, effortlessness. Some being modes I have an interest in but they are too easily posited as ‘good’ at the expense of all kinds of deemed excesses.

So do you think that words like decadence can actually weirdly have a normative effect in that they always have to operate against the markers of the normal?

Yeah and I wonder if you can see the results of that in the fact that the very word ‘decadence’ is diluted enough to be used in copy to describe chocolate, for instance. Although what isn’t?

It’s also interesting how the word and the idea of it are used (opprobriously) in both radical and reactionary rhetoric for describing late phase cultures when things are meant to collapse, and that a marker of this stage is a preoccupation with the decorative. We’re always being reminded of these tyrannical Roman emperors who are so often described in terms of androgyny or effeminacy: in reactionary-capitalist terms, we see this logic tediously invoked for any old transphobic whim, like when in an interview C*mille P*glia suggests that trans fem people and queers suddenly manifest before the collapse of a civilisation, all of this being the corruption of a cismasculine culture and precurser to a new masculine ‘primitive’ stage, with society sweeping in to obliterate these apparently effete cultures. And obviously these assessments brush under the rug (or are entirely oblivious to), whole histories of transness and other gender categories, like third gender, which exist in the cultures they would ultimately classify as primitive. Maybe this is all so tedious it’s almost not worth engaging, but is useful in seeing how these aesthetic laws are invoked daily against trans people and queer people and still shape the contours of living, including received wisdom around taste and artmaking and what is considered measured and what is ‘superfluous excrescences.’ Oh, and we can’t separate the social conception of decadence that emerged from the trials of Wilde from the subsequent violent reception of both homosexuality and the transness in Britain which was exported colonially.

The kind of logic P*glia invokes is so omnipresent in the way that we understand taste and aesthetics, and as you say it totally obliterates histories that don’t treat the decorative and ornamental as simply excessive and superfluous. How do you deal with this problem of ornament, especially when you’re dealing with production from a Marxist point of view? Decadent art-for-arts-sake as one way of explaining ornament stems in many respects from an elitist or aristocratic tradition that doesn’t have to consider the labour involved. How can these two problems be balanced, that on the one hand the ornamental has been denigrated, but then on the other hand that ornament is also this luxury theorised by the elite?

Ornament also has a history of abject horror tied to it in relation to labour and yes, a history of elitism even as it is denigrated by the same elite. Compared to other aesthetic modes, its transgressive, radical potential and history are still neglected. ‘Good honest simplicity’ rarely needs intervening for (though people always are) because it isn’t coded as effeminate and evil in the same way, but of course simplicity has an equally abject history weaponised by the elite. As does ‘moderation’, as does ‘stylistic invisibility’, as does ‘naturalness’. Not to oversimplify, but their aesthetic benefits have long been paraded whereas the extra-aesthetic always exceeds the bounds, or it is hollow and empty – it is either too much or not enough, in ways that are racialised and gendered.

For me ornament just as much calls up other sites of production including a myriad of Yoruba arts, queer Black utilisations of the opulent found in ballroom and adjacent cultures, Black disco, various working-class domestic histories. All these offer sites where production and labour and the value of ornament is different to that of white aristo engagement, and many have been sources for an elite interest in the ornamental in the first place. I’m also reminded of the essay by Abondance Matanda called ‘The First Galleries I Knew were Black Homes’ [in Dead Ink’s essay collection Know Your Place] which really beautifully offers a Black domestic ornamental history, and then for instance work by the scholar Amber Jamilla Musser who looks at the way Black artists have used visual and sensory lustre, i.e. the ornamental, as a strategy which can be radical in its evasion of and resistance to certain kinds of legibility and one that deals with the question of commodification. Her work in turn points to the work of Krista Thompsen who looks specifically at Black cultural production by way of the ornamental category of Bling.

And ornamentality can be relational, or rhetorical or detached from the material (if anything can). And then, of course, ornament doesn’t have to be radical either. There is so much in the ornamental that can sit alongside the radical, partly because of its demoted status and partly just because of what it does, as a form. I think it becomes an off-stage world, which can harbour knowledge, histories and conversations. I always think of the ornamental dimension as this kind of sideways zone, where alterities are going on and seeds of utopia get lodged, different ways of being and experiencing the world, whether this ornament is abstract geometric pattern, braided hair, makeup, music or poetry. So yes, the production of ornament is definitely a fraught and complex problem in all its excess and beyond-ness, but there is so much there that is worth exploring.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.