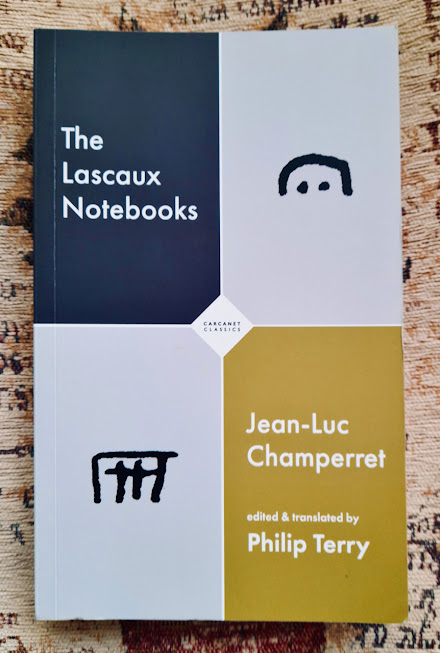

Jean-Luc Champerret, The Lascaux Notebooks,

Trans. by Philip Terry, Carcanet, 2022

read it at Google Books

This newest Carcanet Classic collects the oldest poetry yet discovered, as written down or runed in the Ice Age in Lascaux and other caves in the Dordogne, and now translated—tentatively—into English for the first time. The translation is at two removes, from French versions by the mysterious linguistic genius Jean-Luc Champerret, and then from the striking originals that retain such a sense of early human presence. Philip Terry mediates between the French and those hitherto inscrutable originals. Jean-Luc Champerret's unique contribution to world literature is in his interpretation of the cave signs. And Philip Terry's contribution is to have discovered and rendered this seminal, hitherto unsuspected work into English. The translated poems are experiments, as the drawings may have been to the original cave poets composing them as image and sound. While archaeologists maintain that these signs are uninterpretable, Champerret assigns them meanings by analogy, then—in an inspired act of creative reading—inserts them into the frequent 3 x 3 grids to be found at Lascaux. The results—revelation of Ice-Age poetry—are startling.

Lascaux, a placename standing for the abyssal revelation of the cave paintings discovered there after millennia in darkness, and Notebooks, suggesting a private endeavour, preparation, a work to come. While neither is secret as such, neither was meant for the light. Two intrigues then for the price of one.

Of the notebooks, Philip Terry explains that he was offered a dusty crate found in a chateau under renovation that contained the disintegrating papers of an obscure French poet who had scouted the Lascaux caves as a possible hideout for his wartime Resistance cell in which he worked as a codebreaker (a cell that included “a tall wiry Irishman”). The poems found among the papers are Terry's translations from the French of Champerret's translation into contemporary poetic forms of the signs and symbols painted or carved alongside the famous paintings of animals.

According to The First Signs by the paleoarchaeologist Genevieve von Petzinger, there has been little attention given to the meaning and significance of the signs and, while she doesn't offer a translation herself, she does say they could be humanity's first writing system. This gives retrospective mitigation to Champerret and he uses the freedom to gradually augment their spartan form to create the atmospherics of a domestic Ice Age scene. There are numerous others: descriptions of mountainous landscapes, the killing and butchery of prey, burial rituals, and ceremonies performed by shaman. As the poems follow the seventy signs listed in the back of the collection, the vocabulary is limited and over 380 pages this can be a monotonous read, enlivened by occasional use of prose and the patterning Mallarmé used in Un coup de dés. Even so, in the movement of each poem we sense from a state of deathless being in the world to one of displacement and distance – storytelling – stimulating in the reader an awareness of the profoundest moment in human evolution, which one cannot say of most other books of poetry.

"Movement" and "evolution" may be deceptive words here because everything changed as the first sign was simultaneously carved and read. A space opened in that instant, differing from the animal paintings because they are recognisable as representations of animals, whereas what the signs represent retreats behind their appearance, opening a beyond to their purely communicative value. Yes, the scholars say that the signs must have meant something to those who created them except, in such an act, a world apart was exposed. This is the great secret of the signs; an open secret which nevertheless remains.

What is also an open secret is that there was no Jean-Luc Champerret, no crate of papers, no poems in French. It’s curious then that of the four reviews of that I’ve found of The Lascaux Notebooks only one of them is aware that the author and his poems are inventions. Despite this, two reviewers take on face value Terry’s origin story, which one might think too literary to be true, with the hint of Champerret's connection to Beckett removing the benefit of the doubt. Of course, one cannot expect a reviewer to know an author's previous publications but one might hope they would look up Terry's name and discover that he edited The Penguin Book of Oulipo as well as works by the most renowned Oulipean of all, if not also notice that the blurb for his 2021 novel Bone announces that it was written without “letters with descenders (g, j, p, q, y)”. This prison narrative is in the spirit of the linguistic exercises by which the uninvented Dr Edith Bone maintained her sanity while solitary confinement for seven years; a literary embodiment of the prison-house of language and the unexpected spaces confinement might open, marvellously independent of authorial intention, all of which may have led reviewers to hear the echo of “Sham Perec” in Jean-Luc’s surname. [Update: I now understand one of the reviews didn't mention it in order not to spoil the effect.]

Missing this is perhaps an insignificant detail, a mere point of order, as is the fact that the story of the discovery of the Lascaux cave is itself an invention. Melvyn Bragg's introduction to the recent BBC's In Our Time episode on cave art repeats it and goes uncorrected by his expert guests. In a lecture in 1955, Georges Bataille tells his audience that the story of a dog called Robot falling down a hole and whose rescue led to the discovery was either made up by a journalist or local gossip and that the true story is that a storm uprooted a pine tree and a woman decided to put her dead donkey in the hole that had opened up, telling a local boy she thought it may be the entrance to a tunnel rumoured to lead to a château. Later, the boy and a couple of wartime refugees decided to explore the hole when some other refugees they had arranged to meet in order to give them "a good thrashing" failed to appear.

As I wrote, perhaps insignificant. But at the end of the In Our Time episode, one expert says there is still lots of learn about cave art and while "we're still in the dark to some extent" recent developments in radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology should help to illuminate what's left to learn. For the ancient people, descent into the Stygian darkness of the caves is where they discovered, invented, themselves, and us. Philip Terry's transformation of the signs into poetry and dissimulating its origin may in turn be the proper means to turn our eyes towards that darkness. As Bataille writes elsewhere in a book of poetry and in opposition to poetry:

Poetry was simply a detour: through it I escaped the world of discourse, which had become the natural world for me; with poetry I entered a kind of grave where the infinity of the possible was born from the death of the logical world.

As it is, we're still in the light. - Stephen Mitchelmore

http://this-space.blogspot.com/2022/11/the-lascaux-notebooks-by-jean-luc.html

Although The Lascaux Notebooks is the twenty-first book published by Belfast-born poet and translator Philip Terry, he is a shadowy figure as far as American readers are concerned. He may be best known in the U.S. as the anthologizer of The Penguin Book of Oulipo (2019) or the translator of Georges Perec’s I Remember (Godine, 2014). His own poetry projects have involved virtuosic reformulations of the European canon, among them, Ovid Metamorphosed, 2009; Shakespeare’s Sonnets, 2010; Tapestry, 2013 (the Norman invasion as described by the Bayeaux creators); Dante’s Inferno, 2014 (with Ted Berrigan taking the role of Virgil); and Dictator, 2018 (Terry’s revisiting of Gilgamesh). Besides his translations of Perec and Raymond Queneau, Terry has also produced original poetic works employing their methodologies (Oulipoems 1, 2007 and Oulipoems 2, 2009), most remarkably and successfully in Quennets (2016).

With his latest offering, The Lascaux Notebooks, Terry takes an even more ambitious step backward into the literary gloaming. The book’s premise is the discovery of the notebooks of the French “linguistic genius” Jean-Luc Champerret, author of the forgotten Chants de la Dordogne (1941). Champerret is presented as a mysterious individual who broke the code of signs found on the Dordogne’s most famous prehistoric cave walls. (That he was also a member of the Resistance during WWII ostensibly explains his deciphering facility.) Champerret’s French “translations” of these discovered Upper Paleolithic symbols have been rendered by Terry into English. Terry’s fascinating introduction reads like fiction, which it almost certainly is.

I say “almost,” as Carcanet, the book’s publisher, is presenting the volume with a perfectly straight face. Part of Terry’s introduction was published in the London Review of Books in January without qualification. The online launch on May 18 involved Terry reading from the book, along with an introduction and question-and-answer with the distinguished Marina Warner. Only at times did Warner seem to have trouble keeping her giggles stifled. There is also a truly brilliant faux documentary “preview” for the book in French (both recordings are available on YouTube). Terry’s performance has been so good, I myself sometimes wondered whether I might be wrong about his project’s complete lack of authenticity.

For me, the first textual clue that this might all be an Oulipean-inspired creation had to do with my familiarity with Perec’s An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, published in 1975, where from his cafe table Perec describes in exact detail the comings and goings on the Place Saint-Sulpice, particularly those of Bus 84 which ends at Porte de Champerret. The train line that begins at Porte de Champerret now ends at the Metro stop Bobigny-Pantin-Raymond Queneau. This dual coincidence of Perec/Queneau with the name of Terry’s French hero seemed to me unlikely to be an accident.

I also found it suspicious that there are no actual photographs of Champerret’s notebooks, “for conservation reasons,” only charcoal renderings by Lou Terry (presumably Phillip’s relative or spouse). Clearly, Terry did his research on prehistoric sites. But though Terry thanks Pierre LeBlanc at the Pôle d’Interprétation de la Préhistoire at Les Eyzies (an extensive research facility on France’s prehistoric caves), there is no mention of him or Champerret through the website’s search engine, despite Terry’s assertion that that is where the Champerret materials are currently stored. Terry also makes reference to an article in the “Proceedings of the Oxford Prehistorical Society,” a publication, as well as an organization, that doesn’t seem to exist.

Finally, any new discovery that adds a chapter to the nation’s cultural patrimony would not have gone unnoticed and uncelebrated by France’s cultural bureaus. That someone from the UK provided first publication of France’s earliest work of literature would certainly cause alarm and extensive discussion in French academic and intellectual circles. There had been none that I, at least, had been able to find through online searches. Terry does note (and it feels an awful lot like track-covering) “that there are discrepancies between Champerret’s signs and those at Lascaux today is beyond question.” A long and rather dubious explanation follows, concluding with this philosophical sleight-of-hand: “Many have testified that what we see when in a cave, and what we see in a photograph, are ontologically different.”

My mounting suspicions, however, have only served to increase my delight in Terry’s wonderful book. (And, in fact, he himself “came clean” about the book in a July 6 piece for The Irish Times.)

The fun begins with Terry’s preface which, in diabolically Nabokovian manner, tells us considerably more than we need to know about the circumstances of his discovery. He unnecessarily explains why it took him so long to translate and publish his Champerret findings. A footnote on the book’s second page provides the text of a satirical lyric Terry composed about the vice-chancellor of his university (modeled on Mandelstam’s poem to Stalin) which forced Professor Terry to “lie low” for a few years: “The broad-breasted boss from the north / savours each early retirement like an exquisite sweet.” (If this stab at academic politics doesn’t sound funny to you, then The Lascaux Notebooks isn’t your kind of book.)

The box of Lascaux materials were given to Terry some years before, so he relates, by an architect friend who was renovating a chateau in Southwest France in which Champerret had once resided. There follows the story of Terry’s rediscovery of the yet-unopened box in a dusty corner of his garage. “This time, I opened it — partly out of curiosity, partly to determine whether or not I should throw it in the skip that was taking up the drive.” Among the assortment of colored boxes, notebooks and papers were drawings on postcards, “a little like some of the graphic work of Henri Michaux.” Other visual poems, proposes Terry, recall the work of Apollinaire and Mallarmé.

His interest piqued by the discoveries, Terry then meets up with an elderly French maid who years before had worked at the chateau. He asks her for biographical details about the almost-forgotten figure. When the Lascaux caves were discovered in 1940, it is explained, Champerret of the French Underground went (literally) underground to survey a possible hideout for his anti-Nazi cell. Two years later the chateau was raided by the Gestapo, and Champerret disappeared, never to be heard of again. It was during these clandestine wartime visits, before archaeologists arrived, that Lascaux’s Ice Age poems were first discovered. “During his long, lonely, nervous nights at the chateau,” Terry proposes, “Champerret must have ruminated on what he had seen in the cave, bringing his skills as a code-breaker to bear on the ancient drawings and signs.” (A pseudo-glossary of some of these is provided as an appendix.)

Terry’s elaborate introduction is only the beginning of his ambitious project. Ahead of the 350 pages of translated poems, Terry describes Champerret’s process, setting them out as occurring in five distinct stages. The method involves first identifying each sign’s meaning, then placing each ideogrammic “word” into a heraldic 3×3 grid also found in the caves. A third step produces stanzas of three lines each in Terry’s English. With the next set of versions/revisions, each of the triplet’s successive syllabic lines grows longer. And then in its fifth and “final” verse rendering, there is poetic elaboration or “embellishment,” as well as Dantean terza rima indentation. Terry, significantly, does not provide any examples of Champerret’s original, though the chapters are identified by French nomenclature, such as “Boîte Noire,” “Carnet Bleu,” and “Feuilles Détachées.”

All this sounds, at least for a while, vaguely plausible. In his translation of Champerret’s stages three, four and five (as in this example given in his introduction), the reader is presented with

The eye

of the bison

is the sun

which becomes

The eye

of the bison

is like the bright sun

and ends up as

The white eye

of the black bison

is like a star at night

But by poem three of the first notebook/section (beginning with nine identical signs of stacked circumflexes: ^^^ / ^^^ / ^^^ ), chuckling takes over. In this poem, each teepee-shaped sign is “translated” either as bison, mountains, huts, or crossing, all leading to

A herd of bison

came down from the mountains

leaping and dancing over the crossing

As the book proceeds, inclusion of the all the variants (some now with Champerret experimenting with other grid structures and procedures) is mercifully abandoned, leaving the narrative more readable and swift-moving. Possible line breaks are now sometimes only marked by vertical lines. By page 121, we come to true narrative prose, a sixth stage of Terry’s “translations,” four pages describing the aftermath of a devastating wildfire. The interlude comes at a welcome moment, for it requires a certain determination to work one’s way through several hundred pages of repeated images. The effort is worth it, however, as it reveals gems such as this set of descending similes:

The winking black eye

of the cave’s dark [entrance]

is like the eye of a needle of bone

the impenetrable dark

of the cave’s black heart

is like a night with no moon

the hidden place

where the cave divides

is like the branching of the stag’s antler

Through it all, this poet remains a serious prankster. And Terry’s made-up verses can be extremely amusing. One suggests that truffle hunting in Périgord is an activity reaching back many millennia, a proposal not unlikely to be historically accurate. When we get to the eye-winking “Too many men beside the cooking pot and the fish will burn,” or when the ideogrammic “birdhandhand / birdbushbush” becomes “A bird in the hands is like two in the bushes,” the pull on a reader’s leg becomes undeniable. Declaring dead-pan in a footnote that “the consonance between Paleolithic parietal art and the art of modernism is beyond doubt,” he defends the use of collage technique in his and Champerret’s poems. Some of the more farcical poems display familiarity with the modernist canon:

To say I have eaten

the fruit that

you were keeping in the hut

you will have to

make do with

roots when you break fast

eating the fruit

I thought

how delicious how cold

For me, the poetic lesson of W.C. Williams — how the graceful unrhymed line may capture the simple immediacy of human experience — carries over, despite all the allusive joking involved. The book comes to a close with a series of poems describing the creation of “Paleolithic poetry,”

The man takes

the track leading

to the cave

holding a flint to

the wall he carves

antlers trees

he carves dots

a single feather

a bear’s paw print

finishing up with this poetic statement about the subject matter of Lascaux’s cave art:

So much depends

upon the red bison …

For as page after page of Ice Age poems keep coming, the playfully conceived series of vignettes acquire a poetic reality that is quite moving, touching on matters of love both romantic and familial. In their accretion of repeated detail they forcefully imagine what life and death in Paleolithic hunter society might have been like. (Certain images convincingly “presage” Homeric simile, as “when dawn comes with cold hands.”) What Terry has produced are genuine poems, whatever their source; and the book ends up as something close to a masterpiece. Through Terry’s cinematic imagination, readers experience the sensibility of early man, as though the wall paintings of an archaic hunting culture have indeed come alive:

by the flickering

light of a lamp

he makes out

the brightly coloured

forms of horses

galloping across the

vertiginous walls

of the cave

he looks in

wonder and with

longing at the horses

flying overhead

Terry’s skilled verbal recreation bears comparison to the replicated Lascaux IV that paying tourists are allowed to visit. It is a reconstructed leap, of course, but “taking a leap of the imagination, a leap in the dark,” asks Terry, “is this not quite literally what the bounding Chinese horses lining the ceiling of Lascaux’s Axial Gallery ask us to do by example?”

In his University of Essex biography, Terry describers one of his teaching interests as “a widening of the definition of translation as traditionally and rigidly conceived.” Experimental translation is indeed a significant form of creative writing, in and of itself. But by producing the target text as well as its English rendering, Terry challenges received ideas about the origins, nature and function of the lyric poem; the received poetic canon also becomes subject to radical revision. In short, with this book (as well its experimental predecessors), Terry performs the role of the avant-garde artist.

His radicalism is both conceptural and procedural. He speaks of the need to “trust in the grid” in Carcanet’s recorded event, and one hears in this exhortation something of Oulipo methodology. Another “framing device” employed (at least as Terry indicates in the book’s promotional interview) is the introduction of aleatory procedures. A version of John Cage’s indeterminacy, it would appear, is also part of the Champerret/Terry mode of creative translation. Terry’s seemingly random allusion to the I Ching in his introduction, therefore, is not accidental; it’s a kind of clue. Terry also mentions Mallarmé’s Un Coup de dès, a reference followed up mid-book by pages of oversized graphics, all explained as mimicking Champerret’s “playing freely with line spacing and font size.”

Considering Terry’s interest in French literature and thought, his most important source of inspiration must be Georges Bataille’s Lascaux or The Birth of Art (1955), based in part on his 1952 lecture “A Visit to Lascaux.” Immediately pertinent to Terry’s project is Bataille making note of the “coat of arms” grid on the cave walls, as well as the presence of various writing-like signs. Bataille wonders whether these “obscure symbols,” and others like them, might be ideograms. But perhaps more profound is Bataille’s philosophical proposition concerning the power dynamic between humans and animal, a relationship of mutuality he infers from Lascaux’s wall painting. In his art, the Cro-Magnon painter recognizes in animals a shared presence of “mind,” or in Bataille’s French, “esprit.” Despite the apparent frivolity of Terry’s project, much of this respectful and yet fearful interspecies acknowledgement comes through in his recreations. Post-war Bataille was also especially conscious of the fact that the discovery of the caves occurred at the time of Auschwitz. An echo of this historical awareness may be detected in Terry’s imagined narratives, as in this footnote:

“This poem, with its sinister references to captives being led off into the hills, given the historical context of the compositions, cannot fail to evoke the Nazi roundups which were frequent in both the occupied and non-occupied zones in France during the Second World War.”

And then finally, and most relevantly, Bataille identifies the sanctuary as place of ritual preparation for the Paleolithic hunt. Analogously, formalism (the use of rules of “constraints” in the production of texts) is itself a kind of ritualistic process, so that these repetitive texts effectively recreate some sense of preparatory observance. With its ancient forms of charms and spells, poetry (and certainly the “trick” of literacy) is a form of magic. The shaman is ancestor to the poet; he is one who hears and reports the voices of the past.

I do take issue with two elements of Terry’s proposed narrative of Ice Age poetry. Writing, I would argue, comes very late in the poem’s history, as the first written form of the art dates from the time of Sumer. Even now, the chant and hymnal nature of the poem as we know it continues to refer back to a fundamentally oral tradition. In Terry’s created prehistoric chronology, literacy — even a primitive form of cave-wall literacy— is anachronistic. But this is a quibble, as I acknowledge that such an anachronism is central the book’s imaginative premise.

Which brings me to another canonical problematic: As the oral tradition of early women’s poetry existed, and for the most part continued, outside of written form, their voices have remained mostly unrecorded. While many admittedly have no “lyric gender,” a majority of Terry’s poems are written in what could only be a man’s voice. It has generally been assumed that prehistoric cave painting was the work of male humans, though recent discoveries in France and Spain have brought this received idea into question. A majority of painted outlines of hands at numerous sites in Spain and France are distinctly female; women, therefore, likely painted most of the various images we associate with “the birth of art.” If women form even a portion of the era’s visual art, then the long oral tradition of “women’s poetry” (songs of weaving, as one genre that extends into the Middle Ages) would also find its presence there. And so I’m disappointed that more of the poems in Terry’s collection are not clearly in a female voice, especially given Terry’s wonderful recreation of the voices of the Bayeux Tapestry weavers. There is this lovely triplet in Terry’s Lascaux:

We sit with our sharp needles of bone

round the warm glow of the fire

making necklaces from pierced seashells

And while I hate to deaden the joke with a call for gender correctness, it would have been nice to have some sense that Paleolithic women made more than jewelry. (A footnote pointing out recent archaeological discoveries and something about Champerret’s chauvinism and authorial assumptions, for example, could have been both droll and point-making.)

In any event, through Terry’s shamanism the contemporary reader does seem to encounter the esprit of Paleolithic humans. He dances as a shadow-throwing — if not feather- and antler-headdress wearing — bard. As the word for imagination in French is fantaisie, the English adjective “fantastic” well describes the sum of these poems. (In a sort of Game of Thrones prequel, in fact, a cave-inhabiting, talon-snatching dragon makes an appearance.) Terry quotes a pseudo-letter from the Director of the Musée de L’Homme director to Champerret in 1941, “Your work is pure fantasy.” Exactly. Terry’s observation of Champerret’s purported use of the “Mallarméan breakthrough” summarizes even more perfectly the accomplishment of his own Lascaux Notebooks: “Scientifically, this proves nothing, poetically, it is a tour de force.” - Mary Maxwell

Who are we? Where do we come from? Who or what were the people, the land, the gods who made us? These questions have perplexed and haunted us ever since human beings evolved.

One of the heartlands of our understanding of Upper Palaeolithic man is the southwest of France – more precisely, the courses of the Vézère, Dordogne, Lot and Aveyron and their tributaries. There are several reasons for the density of ancient sites in this region: the plentiful supply of water, which attracted both humans and game animals between thirty thousand and ten thousand years ago; the high plains through which these rivers run, which at that time formed steppe, providing grassland for the untold numbers of reindeer and other migratory animals that moved across them seasonally; and the limestone bedrock through which over millennia the waters have carved enormous and complex underground cave systems. It is this last fact that has impressed itself most firmly on the public imagination, in large part because of the spectacular discoveries of cave art that have been made in this region over the last 160 years.

Of these cave networks, Lascaux is the best known. The story of its discovery is in many ways typical: it was stumbled upon by non-specialists who spotted an unusual hole and decided to explore further. What made this case different is what the individuals encountered. In the very dark days of September 1940, a group of adolescent boys found themselves standing in the great Axial Gallery, surrounded by depictions of wild horses and now-extinct aurochs, depictions so remarkable that this space has been dubbed ‘The Sistine Chapel of Prehistory’.

Within a week, two of France’s most distinguished cave art experts, Henri Breuil and Denis Peyrony, had arrived and embarked on a systematic investigation of the complex. It is in this very short timeframe that The Lascaux Notebooks also has its origin. Jean-Luc Champerret was a local poet who managed to get into the cave almost before the archaeologists, apparently while carrying out reconnaissance for the regional Resistance group (at least according to a now-elderly housemaid who was working in a chateau nearby and whom Philip Terry, the editor of these texts, was able to interview). Champerret, like so many before and after him, was not only impressed by the astonishing artistic achievements at Lascaux but also fascinated by the signs that accompany the paintings. These take many forms: aligned dots, crosses, harpoons, parallel straight and curved lines, tridents, spear throwers, so-called ‘tectiforms’ (hut shapes) and, especially, square grids or lattices.

Subsequent researchers have established definite patterns of distribution of these signs, both in Lascaux and elsewhere, but learned arguments have gone back and forth ever since as to what they signify. That they signify something is not in question. Yet how to interpret the symbols of a long-vanished society? What would the inhabitants of the 50th century make of the ubiquity of crosses in Europe, erected over thousands of years, with no texts or oral tradition handed down to explain them?

The impossibility of the task has not deterred people from trying. We are, after all, a species that specialises in meaning. Champerret was convinced that the signs he saw were a primitive form of writing, and started assigning meanings to the shapes, creating his own personal dictionary of ideogrammatic vocabulary. Intrigued by one of the commonest signs, a grid with nine spaces, he suggested that these might have acted as frameworks for the other symbols, a filled grid being used to convey messages. Acting on this hypothesis, he began devising grids of his own, peopling them with symbols suggestive of how he envisaged Palaeolithic society and beliefs.

It is these grids that are the basis for the poems, notes and prose poems that make up this book. Terry was serendipitously given them in 2006 in a moth-eaten state when visiting a friend near Lascaux. It has been a labour of love to decipher, transcribe and translate them. What emerges is at once idiosyncratic and evocative.

Champerret worked with little or no knowledge of the archaeological research already done in the region and elsewhere – at least, Terry gives us no indication that he had any, though he does give us the dismissive response of Paul Rivet, director of the Musée de l’Homme at the time of the caves’ discovery, to whom Champerret sent his thoughts: ‘Your work is pure fantasy.’ Champerret was of course working without the benefit of all the developments in scientific stratigraphy, ethnoarchaeology, palaeobotany, palaeozoology, field archaeology and radiocarbon, thermoluminescence and uranium-thorium dating that have taken place since the 1940s. Each of these has helped to give a fuller idea of what the world of the hunter-gatherers in southwest France was like.

That’s true also for the signs. For a long time they were, understandably, regarded as incidental to the depictions of fauna, which so astonish us with their beauty and accomplishment. Yet over the last thirty years, extensive, though in some circles controversial, work has been done by leading archaeologists, such as Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams, comparing these signs to similar ones in other parietal art traditions among hunter-gatherers in South Africa, the Americas and Australia, and even interviewing those who still practise wall art. They have concluded that the signs have symbolic shamanic significance. They are not writing exactly, but are certainly pregnant with meaning.

By contrast, Champerret was working alone, relying on intuition and creativity. His method for the most part consisted of choosing nine signs, for instance:

deer deer river

antlers water trees

eyes bush spears

He then worked them up into two short poems:

A herd of deer

are crossing

the river

their antlers

above the water

like trees

we watch

from the bushes

spears raised

*

A herd of deer

are swimming over

the river crossing

their black antlers

rise above the water

like a moving forest

we watch in silence

from amidst the bushes

our tall spears raised

This example is clearly inspired by the famous frieze of reindeer in Lascaux, which do indeed have the appearance of swimming across a river, though the presence of the hunters is Champerret’s own invention.

Elsewhere, Champerret conjures up the day-to-day activities of the hunter-gatherers – cooking, scouting, trapping, making huts and tents, sewing – and, of course, their sacred rituals, dances and the entry into the dark, the underworld, the otherworld of the caves. The cumulative effect of the poems is slowly to build an atmosphere that evokes both the strangeness and the familiarity of the Palaeolithic world:

We sit with our needles

round the fire

making necklaces

snow

has fallen

everywhere

a single mammoth

by the crossing

as night falls

Champerret may indeed have been fantasising when he thought he saw early writing systems, but, surrounded by the hell of occupied France, he succeeded in entering into another reality, another way of being human, led by the extraordinary, leaping, living signs of Lascaux. - Hilary Davies

https://literaryreview.co.uk/poems-of-the-underground

Whilst dedicated cavers continue to dive and squeeze further and further underground, mapping new networks and entering underground ‘rooms’ no-one else has ever seen, others have always preferred to consider archaeological and anthropological findings in depth rather than simply move on. Jerome Rothenberg has translated and anthologised texts under the term ethnopoetics; Clayton Eshelman has synthesized theology, psychology, creative writing and what would now be called eco-criticism to explore the ‘Upper Paleolithic Imagination’; whilst the first (and for a long time only) monograph about the Lascaux caves was written by Georges Bataille.

Much, of course, was made of the 20,000 year-old art found (or re-rediscovered) in 1940 at Lascaux and other caves in the Dordogne region. It fed into fine artists’ obsessions with ‘primitive’ cultures, as well as providing an argument that art had always been important, perhaps pre-dating spoken language, and allowed much conjecture about art as magic, celebration, wish-fulfilment, prophecy, celebration and documentary. What seemed to be missing was any coherent study of the smaller marks in the caves, which were overshadowed by many larger animal images and silhouettes of hands.

Enter Jean-Luc Champerret, an obscure and largely forgotten French author, who took it upon himself to document the symbols found in Lascaux, eventually producing a set of 70 Ice-Age hieroglyphics. He had visited the caves as a member of the Resistance soon after they were found, and upon returning soon after the war was able to translate the groups and grids of marks into word clusters, and then extrapolate them into more and more complex texts or poems. Ignored at the time, Champerret’s neglected research was eventually given to Dr. Terry, a translator and Oulipean writer, when visiting an architect friend in the Dordogne region who had found a crate of Champerret’s papers in a chateau he was then remodelling.

It wasn’t until a few years later, when moving house, that Terry realised what he had been given: a highly original and invaluable work which had not been widely disseminated in its original language, let alone translated and published elsewhere. His academic inquisitiveness and imaginative prowess facilitated this marvellous 400-page edition, which reproduces in full the original cave markings, as well as translated versions and reversions of the cave texts produced by Champerret.

Many are first translated from the images – often found in a 3 by 3 grid, a kind of visual magic square – into simple language, which provides a basic word pattern to build on:

call birds trees

call deer plain

call bear mountains (p 82)

It is then a small step to work this up into a denser, more complex work:

the call

of the birds

fills the trees

the call

of the deer

fills the plain

the call

of the bear

fills the mountains

and on, through a third version to the more poetic fourth and final text:

The shrill song

of the birds

fills the swaying trees

the hoarse bellow

of the red deer

echoes in the river valley

the rasping roar

of the cave bears

fills the black mountains

There is, of course, an element of authorial assumption and intervention, not to mention poetic licence here, something Terry notes he is aware of, but the effect of ‘filling out’ the basic written utterances of our ancient ancestors offers us a new and invigorating insight into our past.

Elsewhere, there are texts expanded into prose poems or stories, as well as more fragmented works (sometimes reminiscent of the works of Sappho) which spill across the page. It is an exhilarating and thought-provoking book that foregrounds the world of Ice Age people, a world that is, as one of the poems says, ‘still etched in the dark earth’. This book will, I am sure be of interest to not only poets but all those interested in history, shamanism, ethnography, codes, caves, dissimulation, creative writing and the roots of documented utterance. It will, I am sure, become an influential and seminal book, one which will illuminate the previously dark and shadow-filled caves of formative language. - Rupert Loydell

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.