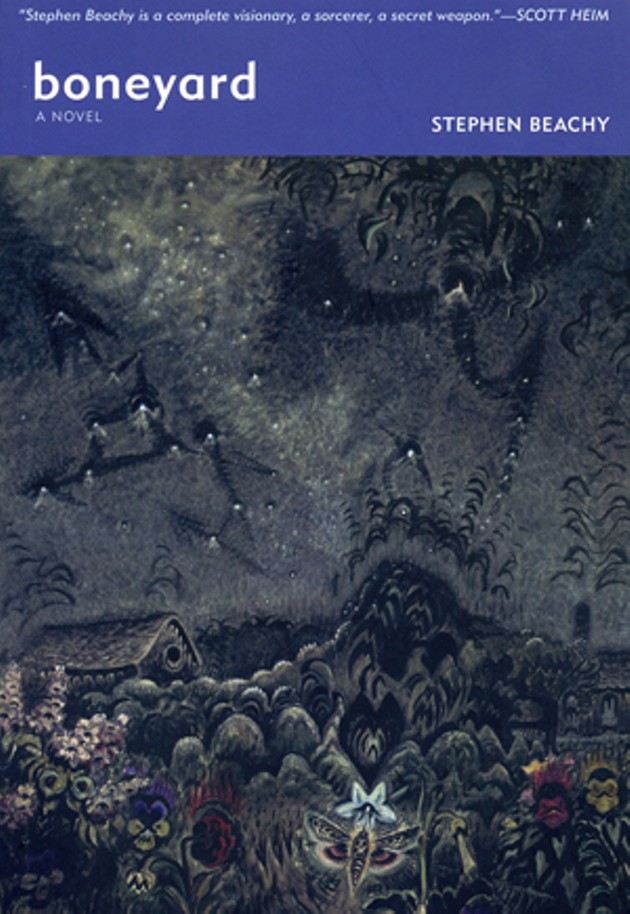

Stephen Beachy, boneyard, Verse Chorus Press, 2011.

read it at Google Book

livingjelly.blogspot.com/

Watch the book trailer here!

In this unusual “collaborative novel,” Jake Yoder, a precocious boy caught between Amish culture and the modern world, sits in his middle-school classroom writing stories at the behest of a stern but charismatic teacher. Jake's stories feature children who are crushed, imprisoned, and distorted, and yet somehow flailing around with a kind of bedazzled awe, trying to find a way out. His characters wander through Amish farms, one-room schoolhouses, South American plains, mental institutions, exotic cities, and prisons; his sentences seem constructed to the beat of an obsessive internal rhythm, and his prose is often haunting and beautiful. The strange logic and disturbing shifts in Jake’s tales reveal a young boy processing intense emotional experiences in the wake of his mother's suicide and his own proximity to the schoolroom shootings at Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania, in 2006. Jake imagines fantastic journeys, magical transformations, and rock stardom as alternatives, it seems, to his own grim reality and the limitations of his life among the Amish.

First part is one of the most amazing texts ever, indulging in every childish fantasy while being inflicted by the darkness of a desolate adulthood, these short stories are fucking perfect.

Part two starts off with a narrative that, frankly, I couldn’t give a shit about (the “bad boy” rock n roll star or whatEVER) but metamorphoses into a really fucking heavy and dark piece of intense writing that really highlights the reality & darkness of life when you’re completely emotionally unavailable.

The things that Beachy/Yoder/Whoever manage to do in this are literally astounding, creating such a realm of despair & affect without relying on a ‘developed character’ to force a reader to empathize with (thus adding a level of distance to the emotional involvement of the reader) [...] - Impossible Mike

Part novel, part puzzle, this is apparently a novel jointly created by an Amish boy and the author. However, given that the author is a specialist in literary trickery, and was the man who unveiled the JT Leroy hoax, this book twists and turns around questions of truth and authorship in an entertainingly dizzying way.

www.huffingtonpost.com/

"Stephen Beachy is a

complete visionary, a sorceror, a secret weapon. boneyard does for the

Amish disapora what Junot Diaz did for Dominicans with The Brief

Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao." - Scott Heim

boneyard is my collaboration with Jake Yoder, a precocious and rather disturbed Amish boy. Jake's stories feature children who are crushed, imprisoned, and distorted, yet somehow flailing around with a kind of bedazzled awe, trying to find a way out. The strange logic and disturbing shifts in Jake's tales reveal a boy processing intense emotional experiences in the wake of his mother's suicide and his own proximity to the schoolroom shootings at Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania, in 2006. Jake imagines fantastic journeys, magical transformations and rock stardom, it seems, as alternatives to the limitations of his life among the Amish. Jake's work is framed with commentary from myself and editor Judith Owsley Brown, in which we offer our very different views on Amish culture, literary context, political strategy in the face of endless imperial wars, the use of psychoactive medications for children, my own mental health, and the reality of Jake Yoder's unconfirmed existence.

"boneyard is a horrifically alluring monster under the bed. It will draw you in on a bone-deep level; overawe you. Existentially profound and emotionally dangerous ... Read this and know how fiction can be a discovery." - Lonely Christopher

boneyard is my collaboration with Jake Yoder, a precocious and rather disturbed Amish boy. Jake's stories feature children who are crushed, imprisoned, and distorted, yet somehow flailing around with a kind of bedazzled awe, trying to find a way out. The strange logic and disturbing shifts in Jake's tales reveal a boy processing intense emotional experiences in the wake of his mother's suicide and his own proximity to the schoolroom shootings at Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania, in 2006. Jake imagines fantastic journeys, magical transformations and rock stardom, it seems, as alternatives to the limitations of his life among the Amish. Jake's work is framed with commentary from myself and editor Judith Owsley Brown, in which we offer our very different views on Amish culture, literary context, political strategy in the face of endless imperial wars, the use of psychoactive medications for children, my own mental health, and the reality of Jake Yoder's unconfirmed existence.

"boneyard is a horrifically alluring monster under the bed. It will draw you in on a bone-deep level; overawe you. Existentially profound and emotionally dangerous ... Read this and know how fiction can be a discovery." - Lonely Christopher

"Intelligent cultural critique wrapped in a

twisty, turny, funny, damning fairy tale that happened neither long ago

nor far away but every day and here." Rebecca Brown

San Francisco author Stephen Beachy

describes his new novel as "collaborative." The exact number of

collaborators is uncertain, but Beachy will be the first to tell you

that one of them is Jake Yoder, a disturbed Amish boy whose fiction is precocious, whose facts don't always check out, and whose name isn't really Jake Yoder.

The book offers this disclaimer early, in a tellingly punctuated "Note from the 'Author.'" It establishes the context of its own creation, a 2006 school shooting in Nickel Mines, Pa. That actually happened, right? I asked myself, before sheepishly Googling it, which only brought more questions: Is this the way we read now? Ignorant and skeptical, not even a page in and putting a book down to get on the computer?

Still, Beachy knows what he's doing. Part of that is interrogating our attachment to the idea of omniscience in narration. Jake Yoder emerges as a sixth grader whose proximity to the shootings was galvanizing: He believed his precocious fiction had caused them. Thereafter Yoder burned his work, which Beachy recovered and reconstructed. It's a fever dream of violent family dynamics and sexual initiations, played out among farms, mental wards, one-room schoolhouses, and its own hall of mirrors.

Next in the prefatory remarks is one Judith Owsley Brown, or JOB, identified as Beachy's editor. Casting doubt on whether Jake Yoder exists at all, she acknowledges the value of Beachy's discovery: "a young Rimbaud, if you will, lurking among the Old Order Amish." (Reportedly, Beachy's grandparents were Amish.) Brown and Beachy enter this boneyard together, batting the confused boy's half-immolated manuscript between themselves in a dance of dueling footnotes. And Beachy, having himself lifted the veil on the JT Leroy literary hoax for New York magazine in 2005, has every right to be weary of the game. But he's invigorated.

What this performance of transparency adds to Yoder's story — an endlessly replayed ruination of innocence that is the novel's core — is for the reader, Beachy's final collaborator, to decide. I'll call it an exquisitely sensitive mindfuck: at once caressing and (consensually) aggressive, as hugely satisfying as it is unsettling. With its hypnagogic obsessiveness and perceivable narrative gearwork, plus pubescent homoeroticism, it's as if the movie Inception had been written as a novel by Gus Van Sant.

Or by Jake Yoder: "He remembers what he learned in the asylum from that ex-paperboy — that you could build a story by intermingling lies with vocabulary words that would imbue it with a kind of magic or what people call madness." - Jonathan Kiefer

The book offers this disclaimer early, in a tellingly punctuated "Note from the 'Author.'" It establishes the context of its own creation, a 2006 school shooting in Nickel Mines, Pa. That actually happened, right? I asked myself, before sheepishly Googling it, which only brought more questions: Is this the way we read now? Ignorant and skeptical, not even a page in and putting a book down to get on the computer?

Still, Beachy knows what he's doing. Part of that is interrogating our attachment to the idea of omniscience in narration. Jake Yoder emerges as a sixth grader whose proximity to the shootings was galvanizing: He believed his precocious fiction had caused them. Thereafter Yoder burned his work, which Beachy recovered and reconstructed. It's a fever dream of violent family dynamics and sexual initiations, played out among farms, mental wards, one-room schoolhouses, and its own hall of mirrors.

Next in the prefatory remarks is one Judith Owsley Brown, or JOB, identified as Beachy's editor. Casting doubt on whether Jake Yoder exists at all, she acknowledges the value of Beachy's discovery: "a young Rimbaud, if you will, lurking among the Old Order Amish." (Reportedly, Beachy's grandparents were Amish.) Brown and Beachy enter this boneyard together, batting the confused boy's half-immolated manuscript between themselves in a dance of dueling footnotes. And Beachy, having himself lifted the veil on the JT Leroy literary hoax for New York magazine in 2005, has every right to be weary of the game. But he's invigorated.

What this performance of transparency adds to Yoder's story — an endlessly replayed ruination of innocence that is the novel's core — is for the reader, Beachy's final collaborator, to decide. I'll call it an exquisitely sensitive mindfuck: at once caressing and (consensually) aggressive, as hugely satisfying as it is unsettling. With its hypnagogic obsessiveness and perceivable narrative gearwork, plus pubescent homoeroticism, it's as if the movie Inception had been written as a novel by Gus Van Sant.

Or by Jake Yoder: "He remembers what he learned in the asylum from that ex-paperboy — that you could build a story by intermingling lies with vocabulary words that would imbue it with a kind of magic or what people call madness." - Jonathan Kiefer

There are

some books that are evocative, immersing reads—books that readers struggle to

break from in order to attend to daily life. There are books that mesmerize,

anesthetize; books that entertain and distract; books that inform, incite. Some

books do all of these things, in patches; some go beyond mesmerizing to reach a

state of breaking, of shifting.

These are

the books that, as if adorned with primordial egg teeth between pages, crack

open some previously undiscovered shell interior to readers and open them uncomfortably

anew—to new expressions, ideas, histories, feelings, questions, forms of

artistry and anxiety. It is, however slightly, a paradigm shift: readers emerge

changed.

Stephen

Beachy’s boneyard, released this October from Verse Chorus Press, was such

a book for me. I found my own change aggravating, like molting; itchy and

uncomfortable, shedding skin and feathers I sunk deeper into boneyard

like a nightmare so beautiful and compelling that it rendered daylight as false

and bittersweet as aspartame. I reacted, strongly, to boneyard,

sometimes as if with allergy, other times with intestinal churning or tears;

sometimes laughing, most of the time eyes wide with a distinct and wondrous

sense of what the fuck?

Told through

a collection of stories with reoccurring characters, settings, and themes, boneyard

is an experience as much as it is a book. The Verse Chorus

Press press packet describes the book as a tale of

“a precocious boy caught between Amish culture and the modern

world, [who] sits in his sixth-grade classroom writing stories at the behest of

a stern but charismatic teacher. Jake’s stories feature children who are

crushed, imprisoned, and distorted, yet somehow flailing around with a kind of

bedazzled awe, trying to find a way out.” I did research to attempt to

understand it—googled, snooped, perused through archived articles and

out-of-print books. I wanted to “get it,” as if the experience of reading it

could be contained in simple understanding. While reading I felt

unmoored—uncertain and suspicious of the author, who never provided the

courtesy of stepping off the page to make it easier for us to navigate his

underworld Grimm fairy land. Or, not his, purportedly: throughout the

book, in footnotes, forewords, back covers, and online blurbs, Beachy

persistently insists that he did not write it. Some guy named Jake Yoder did.

So it’s as

if the path vanishes as soon as you lift your foot from it. Catty caustic

voices hurl insults at one another from bushes to either side as, in front of

you, uncertain still, dark shapes suggest that the path continues, winding

unpredictably through pain, trauma, and tragedy as cyclical as the reoccurring

images of broken bicycle wheels. boneyard is a journey, and your

guide—two of whom questionably exist, one of whom is likely lying—are Verse

Chorus Press editor Judith Brown, Stephen Beachy himself, and, of course, Jake

Yoder; all seem certainly nuts.

Assuming the

reader isn’t nuts, as well—and this does seem rather presumptuous to assume of

anyone, these days—boneyard can be alienating, even in parts grotesque.

It is not an easy or even safe read; it is as troublesome, as real and

repetitive, surreal and hypnotizing as a full blown case of post traumatic

stress disorder. The question remains, however, as to whose trauma we are

journeying through. Yoder’s? Beachy’s? Brown’s? Perhaps it’s a journey through

the reader’s own fucked up heart, or, as Beachy himself suggests, the

collective fucked up heart of us all: an archetypal survivor lost in a forest

of deepening anxieties and elusive dirty rivers. - TT Jax

There

are some books that are evocative, immersing reads—books that readers

struggle to break from in order to attend to daily life. There are books

that mesmerize, anesthetize; books that entertain and distract; books

that inform, incite. Some books do all of these things, in patches; some

go beyond mesmerizing to reach a state of breaking, of shifting.

These are the books that, as if adorned with primordial egg teeth between pages, crack open some previously undiscovered shell interior to readers and open them uncomfortably anew—to new expressions, ideas, histories, feelings, questions, forms of artistry and anxiety. It is, however slightly, a paradigm shift: readers emerge changed.

Stephen Beachy’s boneyard, released this October from Verse Chorus Press, was such a book for me. I found my own change aggravating, like molting; itchy and uncomfortable, shedding skin and feathers I sunk deeper into boneyard like a nightmare so beautiful and compelling that it rendered daylight as false and bittersweet as aspartame. I reacted, strongly, to boneyard, sometimes as if with allergy, other times with intestinal churning or tears; sometimes laughing, most of the time eyes wide with a distinct and wondrous sense of what the fuck?

Told through a collection of stories with reoccurring characters, settings, and themes, boneyard is an experience as much as it is a book. The Verse Chorus Press press packet describes the book as a tale of “a precocious boy caught between Amish culture and the modern world, [who] sits in his sixth-grade classroom writing stories at the behest of a stern but charismatic teacher. Jake’s stories feature children who are crushed, imprisoned, and distorted, yet somehow flailing around with a kind of bedazzled awe, trying to find a way out.” I did research to attempt to understand it—googled, snooped, perused through archived articles and out-of-print books. I wanted to “get it,” as if the experience of reading it could be contained in simple understanding. While reading I felt unmoored—uncertain and suspicious of the author, who never provided the courtesy of stepping off the page to make it easier for us to navigate his underworld Grimm fairy land. Or, not his, purportedly: throughout the book, in footnotes, forewords, back covers, and online blurbs, Beachy persistently insists that he did not write it. Some guy named Jake Yoder did.

So it’s as if the path vanishes as soon as you lift your foot from it. Catty caustic voices hurl insults at one another from bushes to either side as, in front of you, uncertain still, dark shapes suggest that the path continues, winding unpredictably through pain, trauma, and tragedy as cyclical as the reoccurring images of broken bicycle wheels. boneyard is a journey, and your guide—two of whom questionably exist, one of whom is likely lying—are Verse Chorus Press editor Judith Brown, Stephen Beachy himself, and, of course, Jake Yoder; all seem certainly nuts.

Assuming the reader isn’t nuts, as well—and this does seem rather presumptuous to assume of anyone, these days—boneyard can be alienating, even in parts grotesque. It is not an easy or even safe read; it is as troublesome, as real and repetitive, surreal and hypnotizing as a full blown case of post traumatic stress disorder. The question remains, however, as to whose trauma we are journeying through. Yoder’s? Beachy’s? Brown’s? Perhaps it’s a journey through the reader’s own fucked up heart, or, as Beachy himself suggests, the collective fucked up heart of us all: an archetypal survivor lost in a forest of deepening anxieties and elusive dirty rivers.

- See more at: http://www.lambdaliterary.org/reviews/12/28/boneyard-by-stephen-beachy/#sthash.H4Sw6zie.dpuf

These are the books that, as if adorned with primordial egg teeth between pages, crack open some previously undiscovered shell interior to readers and open them uncomfortably anew—to new expressions, ideas, histories, feelings, questions, forms of artistry and anxiety. It is, however slightly, a paradigm shift: readers emerge changed.

Stephen Beachy’s boneyard, released this October from Verse Chorus Press, was such a book for me. I found my own change aggravating, like molting; itchy and uncomfortable, shedding skin and feathers I sunk deeper into boneyard like a nightmare so beautiful and compelling that it rendered daylight as false and bittersweet as aspartame. I reacted, strongly, to boneyard, sometimes as if with allergy, other times with intestinal churning or tears; sometimes laughing, most of the time eyes wide with a distinct and wondrous sense of what the fuck?

Told through a collection of stories with reoccurring characters, settings, and themes, boneyard is an experience as much as it is a book. The Verse Chorus Press press packet describes the book as a tale of “a precocious boy caught between Amish culture and the modern world, [who] sits in his sixth-grade classroom writing stories at the behest of a stern but charismatic teacher. Jake’s stories feature children who are crushed, imprisoned, and distorted, yet somehow flailing around with a kind of bedazzled awe, trying to find a way out.” I did research to attempt to understand it—googled, snooped, perused through archived articles and out-of-print books. I wanted to “get it,” as if the experience of reading it could be contained in simple understanding. While reading I felt unmoored—uncertain and suspicious of the author, who never provided the courtesy of stepping off the page to make it easier for us to navigate his underworld Grimm fairy land. Or, not his, purportedly: throughout the book, in footnotes, forewords, back covers, and online blurbs, Beachy persistently insists that he did not write it. Some guy named Jake Yoder did.

So it’s as if the path vanishes as soon as you lift your foot from it. Catty caustic voices hurl insults at one another from bushes to either side as, in front of you, uncertain still, dark shapes suggest that the path continues, winding unpredictably through pain, trauma, and tragedy as cyclical as the reoccurring images of broken bicycle wheels. boneyard is a journey, and your guide—two of whom questionably exist, one of whom is likely lying—are Verse Chorus Press editor Judith Brown, Stephen Beachy himself, and, of course, Jake Yoder; all seem certainly nuts.

Assuming the reader isn’t nuts, as well—and this does seem rather presumptuous to assume of anyone, these days—boneyard can be alienating, even in parts grotesque. It is not an easy or even safe read; it is as troublesome, as real and repetitive, surreal and hypnotizing as a full blown case of post traumatic stress disorder. The question remains, however, as to whose trauma we are journeying through. Yoder’s? Beachy’s? Brown’s? Perhaps it’s a journey through the reader’s own fucked up heart, or, as Beachy himself suggests, the collective fucked up heart of us all: an archetypal survivor lost in a forest of deepening anxieties and elusive dirty rivers.

- See more at: http://www.lambdaliterary.org/reviews/12/28/boneyard-by-stephen-beachy/#sthash.H4Sw6zie.dpuf

MORE ABOUT boneyard

"I am only a boy in a

city full of trees, but every night I journey. While the other

children of the city lie asleep and dreaming, I travel through the blue

moonlight or the hushed, severe dark if there is no moon ..."

"a restless dream of a book ..." Matthew Stadler

"...mythic, manic and amazing." Michael Lowenthal

"...mythic, manic and amazing." Michael Lowenthal

Should Amish teens read

Artaud, Borges, Cesar Aira, and Heriberto Yepez, experiment with salvia

and mescaline, listen to Lungfish, Nico, and His Name is Alive? Should

they write stories about farms, insane asylums, bondage, enchanted

forests and Argentina? You be the judge.

"The Whistling Song has the energy and abandon of all great first novels. At the same time, the story never gets lostin its long bursts of honest, palpitating language. This book's wild force reminded me of the first time I saw John Malkovich on stage in True West." Jim Carroll

"Stephen Beachy's America -- so fast and freewheeling and dangerous, so full of intoxicated language and pretty lies -- clangs in my head like a firetruck." - Bob Shacochis

Stephen Beachy, Distortion, Queer Mojo (A Rebel Satori Imprint), 2010.

read it at Google Book

It's back ... Distortion was reissued in 2010 by Rebel Satori Press.

During a year that resembles 1991, with war and its aftermath as the constant background noise, Reggie is bouncing around the country, hustling and trying to stave off personal catastrophe. With his own drug-addled sense of history merging with revelation, and his own destiny merging with something he begins to suspect is evil, the scope of the catastrophe seems increasingly cosmic in proportions. In a landscape of airplane disasters, arson fires, emergent viruses and the confounding stew of humanity in the backseats of Greyhound buses, his story intersects a variety of characters equally unmoored from the reference points and false hopes offered by a mutating social order. The barely communicable dreams of indie film directors, occultist producers, punk poets, aspiring actresses and refugees trapped in their own stories of impending doom reduce the quest for love to rubble, leaving only a conflicted yearning for apocalypse in its place. Distortion is a prophetic book peering beneath the surface of American life to discover how much will be risked for the sake of transformation.

It’s the 90s. Reggie, a young hustler, is bouncing around the country trying to stave off personal catastrophe. With his own drug-addled sense of history merging with prophecy, and his own destiny merging with something he begins to suspect is evil, the scope of the catastrophe seems increasingly cosmic in proportions. “Dad” was never a very good idea to begin with. Transmissions from “Mom” suggest an impossible distance fueled by nostalgia for unhappiness. In a landscape of airplane disasters, arson fires, viruses and the confounding stew of humanity in the backseats of Greyhound buses, his story intersects a variety of characters equally unmoored from the reference points and false hopes offered by a mutating social order. Encountering film directors, producers, aspiring actresses and refugees trapped in their own stories of impending doom, his unlikely ascent to something like fame begins to seem like a nightmare.

Distortion works on a different wavelength from most fiction being published today. It gets you initially at an unconscious level, infiltrating your thoughts and presenting a world where the constant drone of TV news and MTV mixes with the hopes and demons of the disenfranchised. Violence, disaster, sex, love, and cruelty ripple through the book like unscrambled broadcasts of a premium cable channel." Jim Tushinski

Some Phantom and No Time Flat are two novellas originally published by Suspect Thoughts in 2006. They will be reissued by Verse Chorus Press in March of 2013.

"Henry Miller said that the moment you have an original thought, you cease to be an American. These 'fissures in the architecture of the Dreamtime' are great unAmerican novellas." Thorn Kief Hilsbery

"Stephen Beachy is a visionary. In these twin novellas, he explores madness and crime with the nocturnal lyricism of empty time and space. Beachy's dear criminals reach an exquisite isolation and so does his reader, a non-place where categories collapse, like freedom and confinement, chaos and lucidity, the angelic and demonic. A harsh dream, and we will never wake." Robert Gluck

The unrooted characters of these novellas find themselves in lives resembling a film, or several films, glimpsed in between fitful dreams. In Some Phantom, an unnamed woman arrives in a strange city, fleeing a violent incident in her past. As she explores the city, takes a job with disturbed children, and fears her old life catching up with her, she must decide whether her increasing paranoia is a form of madness or lucidity. A marriage of The Turn of the Screw and Carnival of Souls, Some Phantom poses questions about the line between madness and memory, between fantasy and abuse.

Criticism for the SF Bay Guardian:

Ascher/Straus

Sex (Acker, Gluck, Goytisolo, de Jesus)

Maya art/Sue Coe

Amish lit

Amish quilts at the DeYoung

Hallucinogenic Fiction

Heart is Deceitful (The JT Movie)

Oliver Stone's World Trade Center

Barbet Schroeder's Terror's Advocate

Michael Winterbottom's The Road to Guantanamo

Anselm Kiefer

Stacey Levine: Frances Johnson

The Gay Gene

Future Evolution

Animals (Lispector, Stacey Levine, Sue Coe, Joy Williams)

Dada: Ball/Hammer

Roberto Bolano: A History of Nazi Literature in the Americas

New York Magazine Article on JT Leroy

Stephen Beachy is the author of two novels, The Whistling Song, and Distortion, as well as a new pair of linked novellas titled Some Phantom/No Time Flat. His fiction has appeared in Best American Gay Fiction, BOMB, The Chicago Review, Blithe House Quarterly, and his nonfiction has appeared in New York Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, and the San Francisco Bay Guardian. In 2005, he bore the dubious honor of unmasking the "Real JT Leroy" in a piece for New York Magazine. Raised by Mennonites "somewhere in the Midwest" and educated in part at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, he now lives in California where he teaches at the University of San Francisco.

The two novellas Some Phantom/No Time Flat share some common themes (wandering adults, possible crimes, sexual abuse, parents and children). Were these simultaneous projects that purposely came together? Did they spring from a similar inspiration?

Some Phantom actually predates No Time Flat considerably. I think I began working on it in the mid 90s, was trying to sell it by 1999 or so. A few editors liked it well enough, but thought it too slight to stand on its own. By the point I realized it wasn't going to happen on its own, No Time Flat existed as about thirty pages plopped down in the middle of a chaotic novel. Once I decided that it actually belonged as the other half of Some Phantom a lot of pieces fell into place. There were thematic links already present, and others emerged, both unconsciously and as the result of very conscious processes of interweaving the two.

What was your intention with the "crime scene investigation" and police report texts in No Time Flat? I found myself consistently wondering if or how they might be connected to the main character, Wade, but was left, I think intentionally, uncertain.

Yes, that's right. I definitely was using them to create narrative tension, and to invite the reader to guess at connections, look for connections and even to make connections that would mimic the process of solving a crime. Looking at those processes and, in some ways subverting them, or at least highlighting the misguided assumptions, biases and conclusions that might stem from these processes, was very much part of the project. There’s something that happens when the suspect of these reports is being incriminated, based on his reading materials – lots of references to murdered children and so on – that implicates the reader, I hope. Since the reader is also reading such a book. They are very funny, these "police reports," using a lot of problemetized "words" in quotation marks, much like the text of the story itself. Did you have a particular voice in mind when writing these?

I looked at actual police reports stemming from the case of those three teenage boys who were railroaded for the murder of three children in West Memphis some years back. These murders were examined in the documentary "Paradise Lost" and its sequel, and almost certainly committed by the step-father of one of the boys. I kept some of the details of that case, with which I hoped I might create a sort of ghostly suggestion of it for those familiar with it, while I added and changed details to suggest elements of both of the novellas. The police reports I looked at were on a website critical of the investigation, and so often included a very skeptical, parenthetical voice that I’m sure leaked into my own version. As well as my own skeptical, parenthetical voice, and the voice of the narrator of No Time Flat, who is close to Wade, but not without a largish ironic distance.

Was there anything that you consciously wanted to avoid in writing about these arguably marginal characters and their arguably marginal desires?

Both books are about the easy shift from one version of events to another, from one way of understanding a story or a memory or a few sporadic facts or observations to another. They’re trying to get at some of the arbitrary ways we make meaning of our lives. So I guess I tried to avoid some of the easiest or most prevalent ways that we seem to do that in America these days. The psychology of the family unit is maybe the most obvious thing that's barely there; I really wanted to treat these two protagonists as people who had formed themselves, or been formed by more random and chaotic forces than mommy and daddy. And while it might not seem obvious, I also tried to work against the idea that the major threat to children is posed by strangers with guns, pedophiles, and murderers wandering the landscape. I personally believe there's a lot more to fear from the parents and institutions that “take care” of children (if I may problematize a phrase here) than from monstrous child-murderers. But I certainly used the expected fears of those familiar monsters for narrative tension, and because I was dealing in a lot of ambiguity I think I created possible readings of events very different from my own.

I also tried to avoid clear labels or diagnoses. I tend to see desires and states of mind as things that exist on a continuum, and the whole concept of “normality” I’ve never found very useful for making sense of my own experience in the world, certainly not when it comes to sexual desire. I don’t know what normal sexual desire would look like, and I’ve certainly never met anyone who had it. So it was interesting with Wade, for example, for me to simply describe some of the things he was thinking and feeling, while avoiding words that put them into categories. Imagining a character with a less firm grasp of some very common cultural references than myself opened up a fun space to defamiliarize things, I think. Fun for me, at least.

I'm really curious about the woman at the center of Some Phantom. Did you have a diagnosis in mind?

I certainly had models in mind, but, as I said, I'm pretty skeptical about diagnoses in general. Psychology, as practiced in America, is pretty barbaric, and whenever you look back at even its recent past, from a distance of say thirty years out, you see this clearly deluded state of affairs, with lobotomies, electroshock therapy, Valium prescriptions for unhappy housewives, and a whole range of common sexual desires treated as pathologies. I think thirty years from now, or hopefully much sooner, our current era will be seen as something akin to the dark ages. Between our blithe medication of children and our usually silly quest for the genes that cause specific behaviors, we're in a seriously confused world of diagnoses and treatments for mental health. Which isn't to say that the woman in Some Phantom doesn't have some serious issues, or that people in general don’t suffer a great deal from mental afflictions. She's sometimes paranoid, certainly, a state of affairs she tries to crush with a kind of hyper-rationality. More than a diagnosis though, I'd again say she's capable of certain states of mind that are quite common. I think most of us are paranoid at times, or at least capable of paranoia. It's a particular misreading of affairs that places the self at the world's center, an understandable impulse in a world in which very few people and no institutions actually care much about other people's goals and desires, except to make use of them, usually to sell something. I wanted to look at how easily one can sort of slip over that line where misreadings become mental illness, I guess. One very important model was The Turn of the Screw, but by way of the film version, "The Innocents", starring Deborah Kerr. Truman Capote wrote the screenplay, and underlined some of the queer subtext which that old queen Henry James had consciously or unconsciously introduced. In the film it's clear that the prim governess, from a strict religious background, is horrified by the little gay boy she's taken charge of and his improper relationship with his rough trade ghost. Also, after I'd written the first draft I saw Herk Harvey's Carnival of Souls", whose rational protagonist, stuck between the world of the living and the world of the dead, seemed very much akin to my protagonist in a bizarre number of ways.

Both of these novellas deal with dark subjects but are consistently hilarious in their delivery. Would you say humor has always been a part of your writing? Would you care to expound for a minute on why it pays to be funny?

Dark humor feels like a particularly accurate worldview, I suppose, or at least one that suits me. The food chain is just grotesque in its horror, and we're all going to suffer and die, but humor is one of the great consolations. You back up out of the human situation a bit and we seem pretty hilarious. We're such nasty and deluded primates, but even our cruelty can be so ridiculous it's comic. I've always at least tried to be funny, sometimes more than others. Without humor I'd feel pompous or smug, I think, which is one reason humor pays. What reader wants to be lectured or to even be shown the world by somebody who takes themselves so absolutely seriously? I can't read Thomas Mann, for example, and I have issues with Joyce; even his attempts at humor come off as the lame attempts of a man utterly convinced of his own genius and the grandeur of his project to humanize himself. There are definitely many writers I love and who've influenced me, maybe most of them, who use dark humor. Joy Williams absolutely, William Burroughs, Ralph Ellison, Denis Johnson, Ascher/Straus, Clarice Lispector, Roberto Bolaño. Good social satirists like Han Ong, Gary Indiana, Jessica Hagedorn and Colson Whitehead are almost always funny and dark.

You are quoted as having said that "Female Convict Scorpion: Jailhouse 41" is one of the greatest films ever made. Please explain.

It was made in 1972, the second in a series of four women's prison films about a silent and unjustly imprisoned convict named Scorpion. I haven’t seen the last two, they’re harder to find, but it’s pretty universally agreed that they pale next to the first two, and it’s the second that really transcends the genre’. The surreal landscapes, special effects, awesome soundtrack and unsentimental feminism elevate this film into one of the strangest, most visually interesting and moving films ever made. Seven escaped female convicts flee through ruined villages, meet ghost women, and fight for their lives. Scorpion’s film persona seems to have been influenced by the spaghetti westerns, Clint Eastwood in particular. Meiko Kaji stars as the stoic, vengeful woman, but she’s much more of a badass than Eastwood ever was. The final revenge fantasy takes the film into the stratosphere. I love B movies that transcend their genre’ to become cosmic; "The Brain That Wouldn’t Die" is another great example, or "X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes," starring Ray Milland.

Because you were the first to unmask Laura Albert as JT Leroy (New York Magazine, October 2005), I thought I'd ask what your afterthoughts were, if any, on how story played out in the media? It seems clear that many agreed there was something insidious about the AIDS angle that made this more than just a clever literary hoax. Has there been anything you've heard or seen since the story broke that particularly shocked or bothered you? I've noticed that JT's website features a faux headline "The Real JT Writes On" and links to interviews with Laura, as well as a couple of dead links to her band Thistle's website. I imagine someone has probably given Laura Albert another book deal?

The last I heard, nobody was going near Laura’s book proposal. I think she’d polluted so many relationships as JT, and left such a trail of lies and fraud that not even the New York publishing world was willing to take the chance on her. That could change, of course. I’ve also heard rumors that she’s working on a documentary. The more interesting documentary (which I’ve been consulted on), however, is being produced by a San Francisco woman Marjorie Sturm. She had been hired by JT at some point to make a documentary, but they killed it when they realized that Savannah Knoop, who played JT in public, would be recognized. Marjorie has all of this footage from early on, and she’s interviewed everyone involved with the story, with the exception of Laura. Nothing Laura does could much shock me any more. Mostly she just runs around threatening to sue people. Laura’s whole angle, since going public, has been that she in a big way really is JT, because she had an abusive childhood, she spent time on the streets, and so on. Taking on a male identity is supposed to be a combination of feminist necessity and fun-loving gender play. But she’s behaved so monstrously that her plea for sympathy as a victim isn’t getting her much traction. People have really focussed on the HIV angle, as the most obnoxious lie, but I’m not so sure. S/he never underlined the HIV thing so much; it was an excuse s/he used early on not to show up in public, because of the unsightly Kaposis’s on JT’s face. But the whole white trash, West Virginia, fundamentalist child-abusers he was supposedly raised by, the grand-daddy who bathed him in lye, the whole JT bio, really, was pretty sick in the way it made use of abuse narratives, combined with common stereotypes, and whatever roots it had in her own dysfunctional personality, a large part of it was always about scamming, and about her own success. At the same time, it does seem to me that Laura was and still is mentally ill, and I have more sympathy with her than many commentators. It’s like Kim Novak in "Vertigo" – another movie with a large presence in the novellas – she’s played this role and made Jimmy Stewart love her, but then she meets him again, no longer the blond aristocratic queen, but a trashy brunette from Salina, Kansas, who wears too much makeup. And she wants him to love her for herself, but he just wants to transform her into the fake woman he remembers. Kim Novak does a brilliant job of capturing the torment of somebody so desperate to be loved that they’ll become whatever the lover wants. And Laura must have been tormented in a similar way.

As far as how it played out in the media, there’s been a lot of focus on Laura, either how evil and fraudulent she is or how misunderstood and merely a fun-loving prankster she is. But I think it’s more complicated and interesting than either of those positions implies. Her actions were very dark, in terms of how she manipulated people, how close she got to a lot of people, and how she used their fantasies against them. But our culture is equally dark, and the literary world is equally dark, and there’s been very little examination of the cultural assumptions that she used and the things that she unintentionally revealed about celebrity culture and the literary world especially, and the outrageous things that people wanted to believe in.

What is your next project?

First there's a more-or-less finished novel that Suspect Thoughts will bring out sometime in the next few years, I believe. I tend to work on several things at once, so that when I get bored or stuck I can move over to a different track. I'm trying to finish these essays I've been working on forever, which are all related but which have divided themselves into two books. The first I'm calling Dreams of Terror and Abuse, which includes pieces about September 11th, Multiple Personality Disorder/Dissociative Identity Disorder, JT LeRoy, the recent shooting at that Amish schoolhouse in Pennsylvania, and one I haven't written yet about my ex-Amish aunt who drowned herself a few years ago, when she was in her 60s. The second one I'm calling Dreams of Transformation, and it's more tightly focused on evolutionary myths: the relationship between Neanderthals and early homo sapiens, the gay gene, the global brain, empaths and sociopaths. Meanwhile, I'm tinkering with another novel that's still too unformed to say much about. At the moment, the models driving it are 1001 Nights and the work of Roberto Bolaño. - novelistic.typepad.com/

Stephen Beachy, an author and adjunct professor at the University

of San Francisco, published his first novel when he was 26, in 1991,

and has worked steadily as a literary critic, journalist and fiction

writer since. But today he is best known as the sleuth who revealed in a

2005 New York magazine story that the alleged writer and former teenage male hooker JT Leroy was actually San Francisco resident Laura Albert.

The story produced a tidal wave of stories about literary hoaxes, but the issues that the Leroy affair raised - the fluid nature of identities, gender politics, the sometimes thin line between insanity and imagination - are central to Beachy's work. In his recently published novellas "Some Phantom/No Time Flat," he summons those themes and laces them with dark humor.

" 'Some Phantom' is a story of a young woman who is fleeing some violence in her past and arrives in a strange city and then takes a job teaching developmentally disabled children," Beachy says of the work, which he wrote in the late '90s. "She starts wondering what's going on around her. Her mental stability becomes more precarious."

The inspiration for "Some Phantom" was the 1961 film "The Innocents," starring Deborah Kerr. "The film deals with what's real, or not real - are there ghosts or aren't there ghosts," Beachy says. "The image of Kerr wrestling with questions of what's real and not real helped form the protagonist of 'Some Phantom.' "

The second novella was written later, and Beachy did not intend to package them, but the two somehow fit. Unlike "Some Phantom," which takes place in a relatively short period of time, "No Time Flat" covers the greater part of the life of a young man who grows up on the Plains, then moves on and sees many disturbing things.

"Both wander in some sense," Beachy says. "I'm very much interested in present-day American cultural anxiety."

Perhaps the best way to think about these novellas is, as Beachy puts it, the spawn in David Cronenberg's "The Brood": twin, hare-lipped dwarfs. "I never really know where I'm going when I write," Beachy says. "I'm fairly serious about the evil hare-lipped dwarfs. They're like organic growths that I birthed and then take off to other places. It's not true for all writers, but what the process is for me is to follow the material rather than force it to where I want to go.

"I'm happiest when I look back, and I'm like, 'Oh I wrote that, how weird.' "

Stephen Beachy, Glory Hole, Fiction Collective 2, 2017.

It’s 2006, and a cloud of darkness seems to have descended over the Earth—or at least over the minds of a ragtag assortment of Bay Area writers, drug dealers, social workers, porn directors, and Melvin, a street kid and refugee from his Mormon family. A shooter runs amok in an Amish schoolhouse, the president runs amok in the Middle East, a child is kidnapped from Disneyland, and on the local literary scene, a former child prostitute and wunderkind author that nobody has ever met has become a media sensation.

But something is fishy about this author, Huey Beauregard, and so Melvin and his friends Felicia and Philip launch an investigation into the webs of self-serving stories, lies, rumors, and propaganda that have come to constitute our sad, fractured reality.

Glory Hole is a novel about the ravages of time and the varied consequences of a romantic attitude toward literature and life. It is about AIDS, meth, porn, fake biographies, street outreach, the study of Arabic verb forms, Polish transgender modernists, obsession, and future life forms. It’s about getting lost in the fog, about prison as both metaphor and reality, madness, evil clowns, and mystical texts. Vast and ambitious, comic and tragic, the novel also serves as a version of the I Ching, meaning it can be used as an oracle. – from the FC2 website

Stephen Beachy, The Whistling Song: A Novel, W W Norton & Co., 1992.

This electric on-the-road novel relates the adventures (mostly midwestern) of Matt, fugitive from an orphanage, hitchhiker into the indifferent 1980s. Here are Huck and Jim titled for today. Stephen Beachy's voice is engaging and subversive as he captures the essence of Matt, a survivor who is streetsmart yet innocent."The Whistling Song has the energy and abandon of all great first novels. At the same time, the story never gets lostin its long bursts of honest, palpitating language. This book's wild force reminded me of the first time I saw John Malkovich on stage in True West." Jim Carroll

"Stephen Beachy's America -- so fast and freewheeling and dangerous, so full of intoxicated language and pretty lies -- clangs in my head like a firetruck." - Bob Shacochis

Stephen Beachy, Distortion, Queer Mojo (A Rebel Satori Imprint), 2010.

read it at Google Book

It's back ... Distortion was reissued in 2010 by Rebel Satori Press.

During a year that resembles 1991, with war and its aftermath as the constant background noise, Reggie is bouncing around the country, hustling and trying to stave off personal catastrophe. With his own drug-addled sense of history merging with revelation, and his own destiny merging with something he begins to suspect is evil, the scope of the catastrophe seems increasingly cosmic in proportions. In a landscape of airplane disasters, arson fires, emergent viruses and the confounding stew of humanity in the backseats of Greyhound buses, his story intersects a variety of characters equally unmoored from the reference points and false hopes offered by a mutating social order. The barely communicable dreams of indie film directors, occultist producers, punk poets, aspiring actresses and refugees trapped in their own stories of impending doom reduce the quest for love to rubble, leaving only a conflicted yearning for apocalypse in its place. Distortion is a prophetic book peering beneath the surface of American life to discover how much will be risked for the sake of transformation.

It’s the 90s. Reggie, a young hustler, is bouncing around the country trying to stave off personal catastrophe. With his own drug-addled sense of history merging with prophecy, and his own destiny merging with something he begins to suspect is evil, the scope of the catastrophe seems increasingly cosmic in proportions. “Dad” was never a very good idea to begin with. Transmissions from “Mom” suggest an impossible distance fueled by nostalgia for unhappiness. In a landscape of airplane disasters, arson fires, viruses and the confounding stew of humanity in the backseats of Greyhound buses, his story intersects a variety of characters equally unmoored from the reference points and false hopes offered by a mutating social order. Encountering film directors, producers, aspiring actresses and refugees trapped in their own stories of impending doom, his unlikely ascent to something like fame begins to seem like a nightmare.

Distortion works on a different wavelength from most fiction being published today. It gets you initially at an unconscious level, infiltrating your thoughts and presenting a world where the constant drone of TV news and MTV mixes with the hopes and demons of the disenfranchised. Violence, disaster, sex, love, and cruelty ripple through the book like unscrambled broadcasts of a premium cable channel." Jim Tushinski

Some Phantom and No Time Flat are two novellas originally published by Suspect Thoughts in 2006. They will be reissued by Verse Chorus Press in March of 2013.

"Henry Miller said that the moment you have an original thought, you cease to be an American. These 'fissures in the architecture of the Dreamtime' are great unAmerican novellas." Thorn Kief Hilsbery

"Stephen Beachy is a visionary. In these twin novellas, he explores madness and crime with the nocturnal lyricism of empty time and space. Beachy's dear criminals reach an exquisite isolation and so does his reader, a non-place where categories collapse, like freedom and confinement, chaos and lucidity, the angelic and demonic. A harsh dream, and we will never wake." Robert Gluck

The unrooted characters of these novellas find themselves in lives resembling a film, or several films, glimpsed in between fitful dreams. In Some Phantom, an unnamed woman arrives in a strange city, fleeing a violent incident in her past. As she explores the city, takes a job with disturbed children, and fears her old life catching up with her, she must decide whether her increasing paranoia is a form of madness or lucidity. A marriage of The Turn of the Screw and Carnival of Souls, Some Phantom poses questions about the line between madness and memory, between fantasy and abuse.

These questions are further elaborated in No

Time Flat -- a distorted reflection, an evil twin, the puzzle inside the

puzzle. Wade is a dreaming boy living an isolated existence on the

American plains. Between the silences of his elderly parents and the

permutations of his own fantasy life, Wade's childhood becomes a kind of

eternity. Haunted by mysterious strangers and by a shooting at his

elementary school, he finally escapes into an adult life of aimless

wandering. Through these desolate landscapes of fleeting connections,

lost children, and unformulated crimes, a nuanced and unsparing vision

of contemporary America begins to emerge.

Criticism for the SF Bay Guardian:

Ascher/Straus

Sex (Acker, Gluck, Goytisolo, de Jesus)

Maya art/Sue Coe

Amish lit

Amish quilts at the DeYoung

Hallucinogenic Fiction

Heart is Deceitful (The JT Movie)

Oliver Stone's World Trade Center

Barbet Schroeder's Terror's Advocate

Michael Winterbottom's The Road to Guantanamo

Anselm Kiefer

Stacey Levine: Frances Johnson

The Gay Gene

Future Evolution

Animals (Lispector, Stacey Levine, Sue Coe, Joy Williams)

Dada: Ball/Hammer

Roberto Bolano: A History of Nazi Literature in the Americas

New York Magazine Article on JT Leroy

Stephen Beachy

Stephen Beachy is the author of two novels, The Whistling Song, and Distortion, as well as a new pair of linked novellas titled Some Phantom/No Time Flat. His fiction has appeared in Best American Gay Fiction, BOMB, The Chicago Review, Blithe House Quarterly, and his nonfiction has appeared in New York Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, and the San Francisco Bay Guardian. In 2005, he bore the dubious honor of unmasking the "Real JT Leroy" in a piece for New York Magazine. Raised by Mennonites "somewhere in the Midwest" and educated in part at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, he now lives in California where he teaches at the University of San Francisco.

The two novellas Some Phantom/No Time Flat share some common themes (wandering adults, possible crimes, sexual abuse, parents and children). Were these simultaneous projects that purposely came together? Did they spring from a similar inspiration?

Some Phantom actually predates No Time Flat considerably. I think I began working on it in the mid 90s, was trying to sell it by 1999 or so. A few editors liked it well enough, but thought it too slight to stand on its own. By the point I realized it wasn't going to happen on its own, No Time Flat existed as about thirty pages plopped down in the middle of a chaotic novel. Once I decided that it actually belonged as the other half of Some Phantom a lot of pieces fell into place. There were thematic links already present, and others emerged, both unconsciously and as the result of very conscious processes of interweaving the two.

What was your intention with the "crime scene investigation" and police report texts in No Time Flat? I found myself consistently wondering if or how they might be connected to the main character, Wade, but was left, I think intentionally, uncertain.

Yes, that's right. I definitely was using them to create narrative tension, and to invite the reader to guess at connections, look for connections and even to make connections that would mimic the process of solving a crime. Looking at those processes and, in some ways subverting them, or at least highlighting the misguided assumptions, biases and conclusions that might stem from these processes, was very much part of the project. There’s something that happens when the suspect of these reports is being incriminated, based on his reading materials – lots of references to murdered children and so on – that implicates the reader, I hope. Since the reader is also reading such a book. They are very funny, these "police reports," using a lot of problemetized "words" in quotation marks, much like the text of the story itself. Did you have a particular voice in mind when writing these?

I looked at actual police reports stemming from the case of those three teenage boys who were railroaded for the murder of three children in West Memphis some years back. These murders were examined in the documentary "Paradise Lost" and its sequel, and almost certainly committed by the step-father of one of the boys. I kept some of the details of that case, with which I hoped I might create a sort of ghostly suggestion of it for those familiar with it, while I added and changed details to suggest elements of both of the novellas. The police reports I looked at were on a website critical of the investigation, and so often included a very skeptical, parenthetical voice that I’m sure leaked into my own version. As well as my own skeptical, parenthetical voice, and the voice of the narrator of No Time Flat, who is close to Wade, but not without a largish ironic distance.

Was there anything that you consciously wanted to avoid in writing about these arguably marginal characters and their arguably marginal desires?

Both books are about the easy shift from one version of events to another, from one way of understanding a story or a memory or a few sporadic facts or observations to another. They’re trying to get at some of the arbitrary ways we make meaning of our lives. So I guess I tried to avoid some of the easiest or most prevalent ways that we seem to do that in America these days. The psychology of the family unit is maybe the most obvious thing that's barely there; I really wanted to treat these two protagonists as people who had formed themselves, or been formed by more random and chaotic forces than mommy and daddy. And while it might not seem obvious, I also tried to work against the idea that the major threat to children is posed by strangers with guns, pedophiles, and murderers wandering the landscape. I personally believe there's a lot more to fear from the parents and institutions that “take care” of children (if I may problematize a phrase here) than from monstrous child-murderers. But I certainly used the expected fears of those familiar monsters for narrative tension, and because I was dealing in a lot of ambiguity I think I created possible readings of events very different from my own.

I also tried to avoid clear labels or diagnoses. I tend to see desires and states of mind as things that exist on a continuum, and the whole concept of “normality” I’ve never found very useful for making sense of my own experience in the world, certainly not when it comes to sexual desire. I don’t know what normal sexual desire would look like, and I’ve certainly never met anyone who had it. So it was interesting with Wade, for example, for me to simply describe some of the things he was thinking and feeling, while avoiding words that put them into categories. Imagining a character with a less firm grasp of some very common cultural references than myself opened up a fun space to defamiliarize things, I think. Fun for me, at least.

I'm really curious about the woman at the center of Some Phantom. Did you have a diagnosis in mind?

I certainly had models in mind, but, as I said, I'm pretty skeptical about diagnoses in general. Psychology, as practiced in America, is pretty barbaric, and whenever you look back at even its recent past, from a distance of say thirty years out, you see this clearly deluded state of affairs, with lobotomies, electroshock therapy, Valium prescriptions for unhappy housewives, and a whole range of common sexual desires treated as pathologies. I think thirty years from now, or hopefully much sooner, our current era will be seen as something akin to the dark ages. Between our blithe medication of children and our usually silly quest for the genes that cause specific behaviors, we're in a seriously confused world of diagnoses and treatments for mental health. Which isn't to say that the woman in Some Phantom doesn't have some serious issues, or that people in general don’t suffer a great deal from mental afflictions. She's sometimes paranoid, certainly, a state of affairs she tries to crush with a kind of hyper-rationality. More than a diagnosis though, I'd again say she's capable of certain states of mind that are quite common. I think most of us are paranoid at times, or at least capable of paranoia. It's a particular misreading of affairs that places the self at the world's center, an understandable impulse in a world in which very few people and no institutions actually care much about other people's goals and desires, except to make use of them, usually to sell something. I wanted to look at how easily one can sort of slip over that line where misreadings become mental illness, I guess. One very important model was The Turn of the Screw, but by way of the film version, "The Innocents", starring Deborah Kerr. Truman Capote wrote the screenplay, and underlined some of the queer subtext which that old queen Henry James had consciously or unconsciously introduced. In the film it's clear that the prim governess, from a strict religious background, is horrified by the little gay boy she's taken charge of and his improper relationship with his rough trade ghost. Also, after I'd written the first draft I saw Herk Harvey's Carnival of Souls", whose rational protagonist, stuck between the world of the living and the world of the dead, seemed very much akin to my protagonist in a bizarre number of ways.

Both of these novellas deal with dark subjects but are consistently hilarious in their delivery. Would you say humor has always been a part of your writing? Would you care to expound for a minute on why it pays to be funny?

Dark humor feels like a particularly accurate worldview, I suppose, or at least one that suits me. The food chain is just grotesque in its horror, and we're all going to suffer and die, but humor is one of the great consolations. You back up out of the human situation a bit and we seem pretty hilarious. We're such nasty and deluded primates, but even our cruelty can be so ridiculous it's comic. I've always at least tried to be funny, sometimes more than others. Without humor I'd feel pompous or smug, I think, which is one reason humor pays. What reader wants to be lectured or to even be shown the world by somebody who takes themselves so absolutely seriously? I can't read Thomas Mann, for example, and I have issues with Joyce; even his attempts at humor come off as the lame attempts of a man utterly convinced of his own genius and the grandeur of his project to humanize himself. There are definitely many writers I love and who've influenced me, maybe most of them, who use dark humor. Joy Williams absolutely, William Burroughs, Ralph Ellison, Denis Johnson, Ascher/Straus, Clarice Lispector, Roberto Bolaño. Good social satirists like Han Ong, Gary Indiana, Jessica Hagedorn and Colson Whitehead are almost always funny and dark.

You are quoted as having said that "Female Convict Scorpion: Jailhouse 41" is one of the greatest films ever made. Please explain.

It was made in 1972, the second in a series of four women's prison films about a silent and unjustly imprisoned convict named Scorpion. I haven’t seen the last two, they’re harder to find, but it’s pretty universally agreed that they pale next to the first two, and it’s the second that really transcends the genre’. The surreal landscapes, special effects, awesome soundtrack and unsentimental feminism elevate this film into one of the strangest, most visually interesting and moving films ever made. Seven escaped female convicts flee through ruined villages, meet ghost women, and fight for their lives. Scorpion’s film persona seems to have been influenced by the spaghetti westerns, Clint Eastwood in particular. Meiko Kaji stars as the stoic, vengeful woman, but she’s much more of a badass than Eastwood ever was. The final revenge fantasy takes the film into the stratosphere. I love B movies that transcend their genre’ to become cosmic; "The Brain That Wouldn’t Die" is another great example, or "X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes," starring Ray Milland.

Because you were the first to unmask Laura Albert as JT Leroy (New York Magazine, October 2005), I thought I'd ask what your afterthoughts were, if any, on how story played out in the media? It seems clear that many agreed there was something insidious about the AIDS angle that made this more than just a clever literary hoax. Has there been anything you've heard or seen since the story broke that particularly shocked or bothered you? I've noticed that JT's website features a faux headline "The Real JT Writes On" and links to interviews with Laura, as well as a couple of dead links to her band Thistle's website. I imagine someone has probably given Laura Albert another book deal?

The last I heard, nobody was going near Laura’s book proposal. I think she’d polluted so many relationships as JT, and left such a trail of lies and fraud that not even the New York publishing world was willing to take the chance on her. That could change, of course. I’ve also heard rumors that she’s working on a documentary. The more interesting documentary (which I’ve been consulted on), however, is being produced by a San Francisco woman Marjorie Sturm. She had been hired by JT at some point to make a documentary, but they killed it when they realized that Savannah Knoop, who played JT in public, would be recognized. Marjorie has all of this footage from early on, and she’s interviewed everyone involved with the story, with the exception of Laura. Nothing Laura does could much shock me any more. Mostly she just runs around threatening to sue people. Laura’s whole angle, since going public, has been that she in a big way really is JT, because she had an abusive childhood, she spent time on the streets, and so on. Taking on a male identity is supposed to be a combination of feminist necessity and fun-loving gender play. But she’s behaved so monstrously that her plea for sympathy as a victim isn’t getting her much traction. People have really focussed on the HIV angle, as the most obnoxious lie, but I’m not so sure. S/he never underlined the HIV thing so much; it was an excuse s/he used early on not to show up in public, because of the unsightly Kaposis’s on JT’s face. But the whole white trash, West Virginia, fundamentalist child-abusers he was supposedly raised by, the grand-daddy who bathed him in lye, the whole JT bio, really, was pretty sick in the way it made use of abuse narratives, combined with common stereotypes, and whatever roots it had in her own dysfunctional personality, a large part of it was always about scamming, and about her own success. At the same time, it does seem to me that Laura was and still is mentally ill, and I have more sympathy with her than many commentators. It’s like Kim Novak in "Vertigo" – another movie with a large presence in the novellas – she’s played this role and made Jimmy Stewart love her, but then she meets him again, no longer the blond aristocratic queen, but a trashy brunette from Salina, Kansas, who wears too much makeup. And she wants him to love her for herself, but he just wants to transform her into the fake woman he remembers. Kim Novak does a brilliant job of capturing the torment of somebody so desperate to be loved that they’ll become whatever the lover wants. And Laura must have been tormented in a similar way.

As far as how it played out in the media, there’s been a lot of focus on Laura, either how evil and fraudulent she is or how misunderstood and merely a fun-loving prankster she is. But I think it’s more complicated and interesting than either of those positions implies. Her actions were very dark, in terms of how she manipulated people, how close she got to a lot of people, and how she used their fantasies against them. But our culture is equally dark, and the literary world is equally dark, and there’s been very little examination of the cultural assumptions that she used and the things that she unintentionally revealed about celebrity culture and the literary world especially, and the outrageous things that people wanted to believe in.

What is your next project?

First there's a more-or-less finished novel that Suspect Thoughts will bring out sometime in the next few years, I believe. I tend to work on several things at once, so that when I get bored or stuck I can move over to a different track. I'm trying to finish these essays I've been working on forever, which are all related but which have divided themselves into two books. The first I'm calling Dreams of Terror and Abuse, which includes pieces about September 11th, Multiple Personality Disorder/Dissociative Identity Disorder, JT LeRoy, the recent shooting at that Amish schoolhouse in Pennsylvania, and one I haven't written yet about my ex-Amish aunt who drowned herself a few years ago, when she was in her 60s. The second one I'm calling Dreams of Transformation, and it's more tightly focused on evolutionary myths: the relationship between Neanderthals and early homo sapiens, the gay gene, the global brain, empaths and sociopaths. Meanwhile, I'm tinkering with another novel that's still too unformed to say much about. At the moment, the models driving it are 1001 Nights and the work of Roberto Bolaño. - novelistic.typepad.com/

Out loud: Stephen Beachy

Reyhan Harmanci

The story produced a tidal wave of stories about literary hoaxes, but the issues that the Leroy affair raised - the fluid nature of identities, gender politics, the sometimes thin line between insanity and imagination - are central to Beachy's work. In his recently published novellas "Some Phantom/No Time Flat," he summons those themes and laces them with dark humor.

" 'Some Phantom' is a story of a young woman who is fleeing some violence in her past and arrives in a strange city and then takes a job teaching developmentally disabled children," Beachy says of the work, which he wrote in the late '90s. "She starts wondering what's going on around her. Her mental stability becomes more precarious."

The inspiration for "Some Phantom" was the 1961 film "The Innocents," starring Deborah Kerr. "The film deals with what's real, or not real - are there ghosts or aren't there ghosts," Beachy says. "The image of Kerr wrestling with questions of what's real and not real helped form the protagonist of 'Some Phantom.' "

The second novella was written later, and Beachy did not intend to package them, but the two somehow fit. Unlike "Some Phantom," which takes place in a relatively short period of time, "No Time Flat" covers the greater part of the life of a young man who grows up on the Plains, then moves on and sees many disturbing things.

"Both wander in some sense," Beachy says. "I'm very much interested in present-day American cultural anxiety."

Perhaps the best way to think about these novellas is, as Beachy puts it, the spawn in David Cronenberg's "The Brood": twin, hare-lipped dwarfs. "I never really know where I'm going when I write," Beachy says. "I'm fairly serious about the evil hare-lipped dwarfs. They're like organic growths that I birthed and then take off to other places. It's not true for all writers, but what the process is for me is to follow the material rather than force it to where I want to go.

"I'm happiest when I look back, and I'm like, 'Oh I wrote that, how weird.' "

Stephen Beachy, Glory Hole, Fiction Collective 2, 2017.

It’s 2006, and a cloud of darkness seems to have descended over the Earth—or at least over the minds of a ragtag assortment of Bay Area writers, drug dealers, social workers, porn directors, and Melvin, a street kid and refugee from his Mormon family. A shooter runs amok in an Amish schoolhouse, the president runs amok in the Middle East, a child is kidnapped from Disneyland, and on the local literary scene, a former child prostitute and wunderkind author that nobody has ever met has become a media sensation.

But something is fishy about this author, Huey Beauregard, and so Melvin and his friends Felicia and Philip launch an investigation into the webs of self-serving stories, lies, rumors, and propaganda that have come to constitute our sad, fractured reality.

Glory Hole is a novel about the ravages of time and the varied consequences of a romantic attitude toward literature and life. It is about AIDS, meth, porn, fake biographies, street outreach, the study of Arabic verb forms, Polish transgender modernists, obsession, and future life forms. It’s about getting lost in the fog, about prison as both metaphor and reality, madness, evil clowns, and mystical texts. Vast and ambitious, comic and tragic, the novel also serves as a version of the I Ching, meaning it can be used as an oracle. – from the FC2 website

“Glory Hole is a capacious, sinuous, complex book that pursues the interlinked stories of characters on the margins of social classes, conventions, and sexual/gender structures in ways that reveal the authentic, everyday fabric of their lives.” —Matthew Roberson

“Glory Hole is a novel that provides the glories of story with none of its limitations. Offering all the sensemaking forms of narrative without ever coalescing into any one binding tale, it is a gorgeous, shape-shifting trapdoor into the void, the only true home you’ve ever really known.” —Elisabeth Sheffield

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.