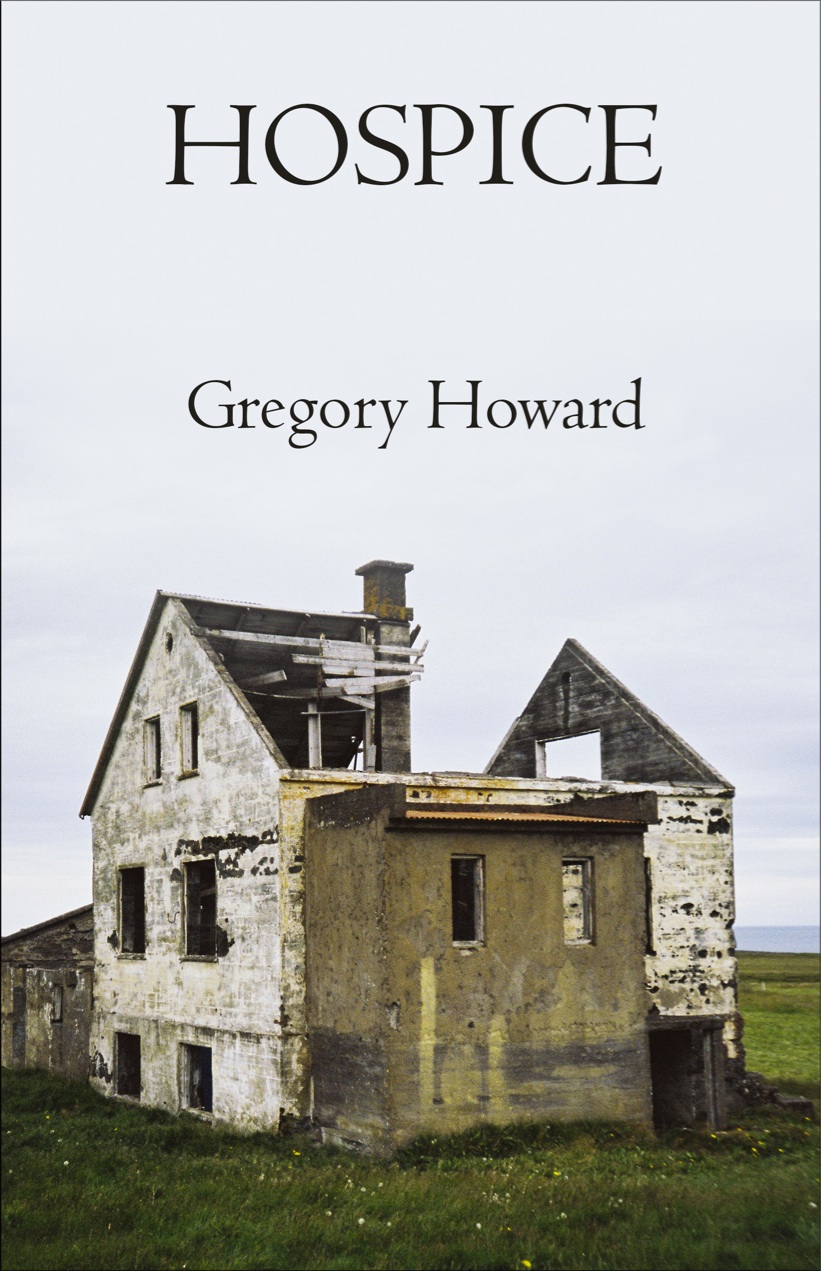

Gregory Howard, Hospice, Fiction Collective 2, 2015.

gregoryhoward.net/

Here at The Collagist.

And here at Trickhouse.

When Lucy is little something happens to her brother. He disappears for months and when he returns he’s not the same. He’s not her brother. At least this is what Lucy believes. But what actually happened?

Comic, melancholy, haunted, and endlessly inventive, Gregory Howard’s debut novel Hospice follows Lucy later in life as she drifts from job to job caring for dogs, children, and older women—all the while trying to escape the questions of her past only to find herself confronting them again and again.

In the odd and lovely but also frightening life of Lucy, everyday neighborhoods become wonderlands where ordinary houses reveal strange inmates living together in monastic seclusion, wayward children resort to blackmail to get what they want, and hospitals seem to appear and disappear to avoid being found.

Replete with the sense that something strange is about to happen at any moment, Hospice blurs the borders between the mundane and miraculous, evoking the intensity of the secret world of childhood and distressing and absurd search for a place to call home.

“Howard's enchanting Hospice obeys its own magical inner logic with excellent prose and a sadness that will split open hearts. You have in your hands a story that is inquisitive, gripping, and triumphant.”—Deb Olin Unferth

“In Gregory Howard’s beautiful, brilliant first novel, stories spill out of other stories to swim, swirl, dance (sometimes giggling, sometimes smiling gravely), and collide. One thinks of the Calvino of Invisible Cities, to be sure, but also of Bruce Chatwin and his In Patagonia, in each of which a highly inventive voyager goes wandering through the world and/or through the world’s endless tales of itself. Still, deeply felt loss is the engine of the ludic impulse in Hospice, and the many games played, rituals enacted and songs sung by its characters evoke, with grace and power, our oldest truths, our most challenging conundrums, and the exhilarating ebb and flow of our sleep-wrapped lives.” —Laird Hunt

In this dreamlike novel, a young woman moves through a series of strange jobs and wrestles with haunting childhood memories.

It begins with a sudden and jarring scene: a boy and a girl and a rock and a game that suddenly turns ritualistic and violent. It casts its shadow over the story that’s told in the pages that follow. “Then she found herself caring for the memory of an old woman’s dog,” writes Howard. That “she” is Lucy, the novel’s protagonist and the grown-up version of the girl encountered on the first page. In the book’s first section, she takes a job watching an elderly woman’s nonexistent dog and soon bonds with two neighborhood children. She tells them strange stories that read like ephemeral folk tales; in the second section, those are given a new dimension, as the story of Lucy’s past relationship with her brother is fleshed out. There’s a mysterious disappearance, and an even more mysterious return, as the young Lucy begins to suspect that the returnee may no longer be her brother. Identities blur here, a feeling accentuated by Howard’s fondness for using descriptions (“the girl”) in lieu of proper names. It lends the novel as a whole an archetypal quality, even as Lucy’s progression through a series of strange jobs continues. Late in the novel, one character tells Lucy, “You’re like the goddamned Mona Lisa of melancholy,” and it’s a brief moment of self-awareness, an acknowledgement of the book’s essential mood.

As Lucy progresses through surreal landscapes, her journey highlights experiences both delightful and sinister—a haunting take on one life on society’s margins. - Kirkus Review

As Lucy progresses through surreal landscapes, her journey highlights experiences both delightful and sinister—a haunting take on one life on society’s margins. - Kirkus Review

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.