Marlene van Niekerk, The Swan Whisperer: An Inaugural Lecture, Trans. by Marius Swart and the author, Sylph Editions, 2015.

“What does one teach when one is a teacher of Creative Writing? The true? The good? The beautiful? Should one teach criticism, fantasy, or faith? What is the use of literature? What is its place on the greater canvas of human endeavours? And perhaps I should also ask: Can a story offer consolation?”

Voluminous texts have been penned to examine questions such as these, and yet within the 18 pages that lie ahead once the illustrations have been accounted for, is our esteemed professor at the lectern is planning to explore them all? No, she is going to tell a story, offer a fable within a fable, share an experience that she claims rendered these questions irrelevant for her.

What plays out in this inventive and thoughtful allegorical tale is an exploration of the relationship between language and meaning, meaning and truth, truth and the stories we tell which, in turn, leads back to language. Van Niekerk casts herself in the role of the skeptic. At the outset she is busy with the final revisions on a novel that is almost complete. Around her, the rest of her life and responsibilities have been suspended while she survives on frozen dinners and ignores her untended house and garden. The last thing she is prepared to welcome at this moment is a 67-page letter from a former student who, she discovers, is writing from a hospital bed in Amsterdam. She had recommended him for a student fellowship in the city with the thought that the change of place might finally help this pale, anxious young man finish off his MA and move on. But she is certain without reading beyond the first few paragraphs that there is little hope for him and most certainly nothing in his massive missive for her.

And so it goes. After reading a little further, she tucks his letter into a drawer and forgets about it until an unusual package arrives: a dummy of her new novel in which he has written notes and dates, along with 16 cassette tapes. Gradually she will be drawn into the story he wants – no, needs – to share. Cynically she reads about how her student, Kasper Olwagon, believes he has discovered, quite magically almost, an unusual homeless man who seems to have an uncanny ability to summon swans to himself. He watches the man for a while and ultimately takes this vagrant home. He longs to know how this apparent ‘swan whisperer’ calls to the magnificent birds, but for all of his efforts, Kasper is unable to encourage or help him to speak.

In his long letter, Kasper anticipates his professor’s reaction, but he persists and over time, as she is drawn into the mystery and returns repeatedly to his letter for clues. She reads about his attempts to extract meaning from the murmurings he believes he heard, his desire to translate the language of swans. She hears in his efforts echoes of Afrikaans. Slowly she will begin to understand the meaning of the cryptic note that accompanied his parcel containing the book and tapes. The last words he wrote to her were: “Farewell to the worlds of will and representation!” As readers we are invited to follow the entwined journeys of student and teacher to that place where all of those questions posed at the beginning seem to be archaic, irrelevant. And once those rhetorical questions are left behind, one begins to appreciate the expanse of the impossible space contained in this small book.

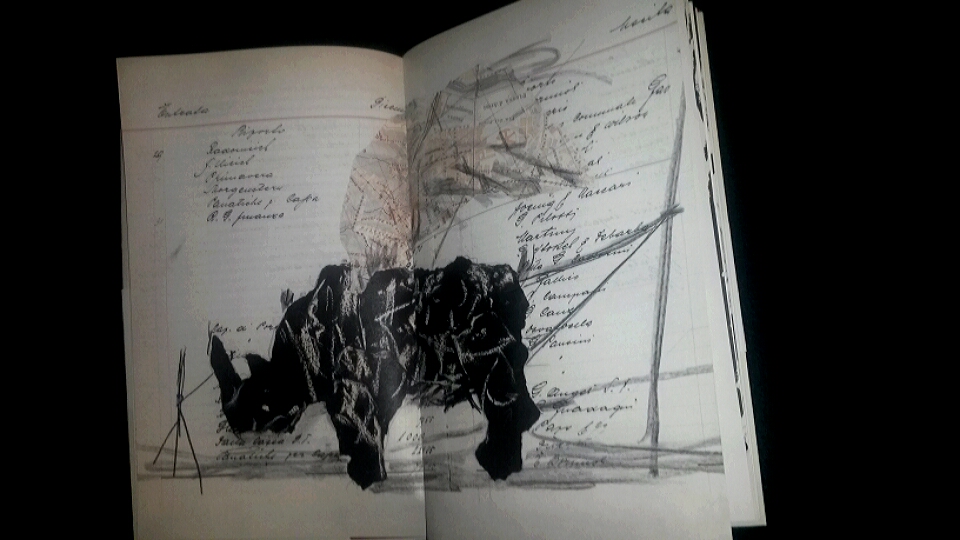

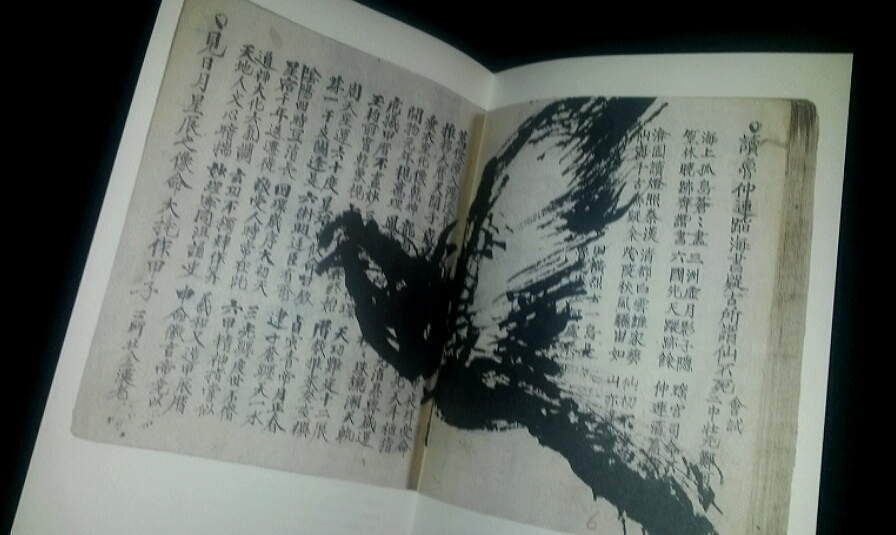

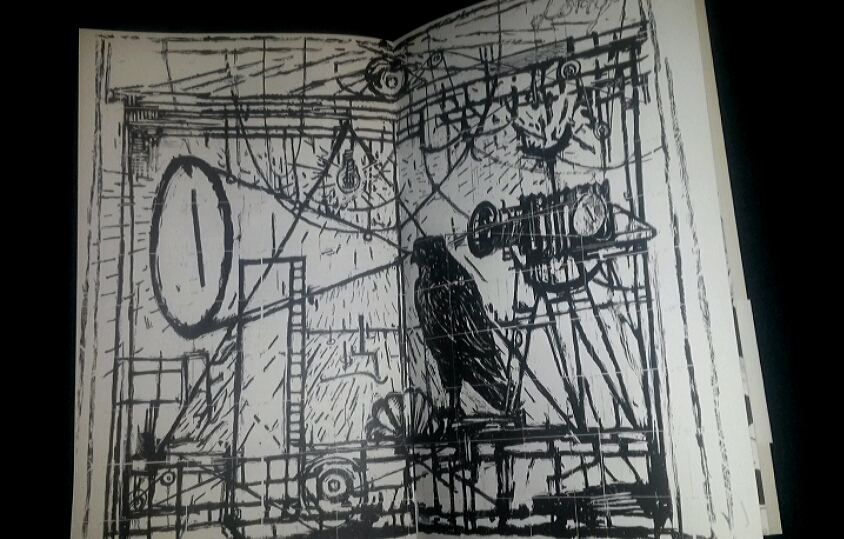

In his long letter, Kasper anticipates his professor’s reaction, but he persists and over time, as she is drawn into the mystery and returns repeatedly to his letter for clues. She reads about his attempts to extract meaning from the murmurings he believes he heard, his desire to translate the language of swans. She hears in his efforts echoes of Afrikaans. Slowly she will begin to understand the meaning of the cryptic note that accompanied his parcel containing the book and tapes. The last words he wrote to her were: “Farewell to the worlds of will and representation!” As readers we are invited to follow the entwined journeys of student and teacher to that place where all of those questions posed at the beginning seem to be archaic, irrelevant. And once those rhetorical questions are left behind, one begins to appreciate the expanse of the impossible space contained in this small book. The Swan Whisperer is the latest addition to the “Cahier Series”, a joint project of the Center for Writers and Translators at the American University of Paris and Sylph Editions. Eminent writers and translators are invited to offer their reflections on writing, on translating, and on the intersection between the two activities. Each volume is accompanied by illustrations. Here, the striking black and white drawings by William Kentridge act almost as a visual soundtrack. His work has a tendency to explode off the page. The images complement the story by exploring the relationship between artists, animals and language. The text is translated from the Afrikaans by Marius Swart and the author.

The Swan Whisperer is the latest addition to the “Cahier Series”, a joint project of the Center for Writers and Translators at the American University of Paris and Sylph Editions. Eminent writers and translators are invited to offer their reflections on writing, on translating, and on the intersection between the two activities. Each volume is accompanied by illustrations. Here, the striking black and white drawings by William Kentridge act almost as a visual soundtrack. His work has a tendency to explode off the page. The images complement the story by exploring the relationship between artists, animals and language. The text is translated from the Afrikaans by Marius Swart and the author.

I have to add that this particular volume held a special appeal for me. This spring I read, for the first time, Marlene van Niekerk’s magnificent novel Agaat. Not only is this a complex, deeply moving story; but the way that language is evoked and brought into play presented a challenge well met by the translator, Michiel Heyns. Not long after this encounter I made my first visit to South Africa and I had the singular pleasure of experiencing William Kentridge’s installation “The Refusal of Time” at the National Gallery in Cape Town. It was, I felt, like a command performance as no one else even ventured into the room beyond a quick glance at the door. Their loss and one of my fondest memories of my stay in the city.

And now I have both artists together in this enchanting and thought provoking book. - roughghosts.wordpress.com/

“Honorable rector,” begins Man Booker International Prize-shortlisted Marlene van Niekerk’s “lecture”, The Swan Whisperer, “what does one teach when one is a teacher of creative writing?”

Instead of analysis, in this slim pamphlet she slips the bounds of the academic format to offer her audience a story: “Perhaps some clarity could be reached by exposing the entire episode to a critical audience such as yourselves.” This entails the South African author becoming a character in her own narrative.

“No desire without technique, and no meaning without rhetoric,” grumbles the irritable “van-Niekerk-as-narrator,” who is a writing tutor at “an institute of higher learning where there is no longer any place for astonishment, fear, or fascination”.

Her teaching approach consists of aphoristic injunctions to shorten, to “stick to the knitting”, to show not tell and, above all, to “write what readers want”.

That is until she receives a series of mysterious letters from an intriguing but troubled ex-student, Kaspar Olwagen, whom she remembers contrary to her “laws”, felt for his writing pen in his breast pocket “as though he first wanted to touch his heart”. As well as letters, Olwagen sends cassettes, another indicator of his analog obsolescence.

The Swan Whisperer offers the delight of not one, but two unreliable narrators. The “van Niekerk” of the book exists on “frozen meals from Nice and Easy,” which she eats among a debris of “speeding tickets and bills”.

She constantly loses Olwagen’s letters, puts them aside in irritation or absent-mindedness.

“I never replied,” the writing teacher says. “This is the first time I have ever spoken of my neglect.”

Kaspar, says “van Niekerk”, should have been a philosopher, not a writer. He insists on “ideas”. But what she finds most irritating is that, given her teaching, and even the right environment (a luxurious grant to visit “a writer’s paradise” in Amsterdam), her student cannot seem to be able to write.

Of course communicating this to his teacher by letter, he does write and not in everyday language. We couldn’t take Kaspar’s style on its own. The beauty (and there is beauty!) in his high-flown flourishes and romantic concepts must be framed by “van Niekerk’s” down-to-earth scorn or it would be indigestible.

Nevertheless it is in the gap produced between the two writing styles that The Swan Whisperer is able to ask us how we enjoy reading and why.

“Writing and living coincide completely in this letter,” writes Kaspar, who tells how though “overbred, neurotic, afraid of germs, [he] offers accommodation to a grimy maladjusted stranger,” the “Swan Whisperer,” a man who appears to be homeless and whose conversation makes no apparent sense. His strange guest produces a third style of communication: he speaks in the tongues of angels.

But The Swan Whisperer deals not only with literature as a philosophical investigation of language. It is also a deeply political book. “Fiction can no longer console us,” protests Kaspar. “The terror of our fatherland robs the narrative imagination of desire and determination ... we have to become brutal collectors of facts.”

Van Niekerk is a South African writer in Afrikaans and Dutch as well as English and is acutely aware of the difficulties of depicting a post-apartheid South Africa in any of these languages.

Her query, “What does one teach when one is a teacher of creative writing?” prompts the consequent question: what can, and should, a writer write?

The book is not an answer to the question of the mystery of writing, but a delineation of the mystery itself – a depiction of the space of “translation” in which the reader, with greater, or lesser difficulty, interprets what is written – and that (as it must be for the “van Niekerk” of the story) is achievement enough.

“I wrote in the margin: ‘Delete the ideas!’,” says “van Niekerk”. “[Kaspar] simply could not achieve the narrative resolution of meaning and minutiae.”

The illustrations in this gorgeous Cahier edition make it clear that The Swan Whisperer is a book about its own hors-texte, but this is one book whose pages I cannot bring myself to annotate. And, though they touch me, I will also leave untouched those pages illustrated by artist William Kentridge, which explode in a violence of ink. - Joanna Walsh

For some time now I’ve been reading The Swan Whisperer over and over as if under a spell, driven by the idea that what links the swan in the title and the words in the text is sound. The word “swan” comes from the Indo-European root “swen-”: “to sound.” And according to some versions of the legend, Orpheus was transformed into a swan after his death.

Words into sound, through a whisper. I try to stitch these elements together, then realize that probably the verb to use shouldn’t be stitch but say, or speak.This is a tale of transmission, disappearance, and utterance, of writing as it hovers at the edge of language, trafficking with the ephemeral and the unreliable; challenging the primacy of the written text through a compelling reflection on flow and interference, rhythms and non-origin. A tale of listening as the rebeginning of writing; of people missing but resounding through words whose meaning is lost (or maybe it was never there completely): it has to be made anew every time. A story of speech emerged from and given back to birds, wind and water, a story of speech into landscape. A tale of writing as divining and impure continuity.

***

The Germanic word for magic formula is galdr, derived from the verb galan, ‘to sing,’ a term applied especially to bird calls.-Mircea Eliade, Shamanism

Marlene van Niekerk likes to talks with owls. “The fellowship of breath,” the South African writer calls those birds in a short interview with The Guardian, on the occasion of her nomination for the International Man Booker Prize in 2015. The reference to breath leads me to recall the old meaning of the word “psyche” as air, an element connecting inner states with the sensuous world; and the ancient notion of birds as spirit visitors carrying the whispers and voices of the lost and missing ones, or of birds as originators of human language. In the same interview Van Niekerk mentions Wordsworth’s poem There Was a Boy, about a boy who talks with owls and then is lost in “a pause / Of silence such as baffled his best skill.” Tellingly she refers to Seamus Heaney’s reading of the poem in Finders Keepers. “Skill is no use anymore [to the boy/poet],” Heaney writes, “but in the baulked silence there occurs something more wonderful than owl-calls. As he stands open like an eye or an ear, he becomes imprinted with all the melodies and hieroglyphs of the world; the workings of the active universe […] are echoed far inside him.” The Swan Whisperer is also a story of voice dissolved into the landscape, transformed into a different substance and texture, different but present. It stretches the understanding of language into what is concealed or not yet heard, and farther out into the wild nature of landscape, until language becomes “the very voice of the trees, the waves, and the forests,” to borrow Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s words from The Visible and the Invisible.

Owls, writing, and birdsong. For the Koyukon people of Alaska the owl is the supreme prophet of birds: it “tells you things.” According to Vedic mythology, as I learn from Roberto Calasso in Literature and the Gods, “the meters […] turned themselves into birds with bodies made of syllables.” For the Kaluli of Papua New Guinea, as ethnomusicologist Steven Feld reports extensively in Sound and Sentiment, “‘bird sound words’” have “‘insides’” and “‘underneaths’”; they “alter the framing of interactions, moving them onto a plane where underlying feelings, emotions and thoughts associated with loss come to the listener’s mind.” Turned over, words show more than one side to themselves. A bird appears at a key point in Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet, harbinger of transformation through the disruption of rational language: “Belzi Ra Ha-ha Hecate Come! / Descend upon us to the sound of my drum / Ikala Iktum my bird is a mole / Up goes the Equator and down the North Pole.” And in another story of unhinged language, Gert Jonke’s Awakening to the Great Sleep War, birds are seen as winged alphabet letters trying to arrange themselves “even when there’s not much to say.” Are syllables, alphabets, and hearing trumpets enough, to enable a subject to listen, record, write beyond the acquired channels of linguistic representation and transmission devices? The characters in this tale suggest otherwise.The Swan Whisperer begins as a public address and ends with an incantation.

It begins as a formal lecture and ends, through various reports and erasures of utterance, on the edge of form.

Its pages hold words about getting lost and about to get lost.

Three characters in the story: the narrator, a creative writing professor called Van Niekerk, like the author (who places herself from the outset in a complex mise-en-abyme where person becomes character and back: the embodiment of a necessary Janus-like gaze spanning fact and fiction); a creative writing student the professor calls Kasper Olwagen (but is this his real name? We never find out) who is stuck in a writer’s block, disappears, and later contacts his teacher through various devices; and an elusive Swan Whisperer, encountered by Kasper on the canals of Amsterdam, who can communicate with birds.

The teacher is reluctant to read, the student cannot write, the Swan Whisperer does not speak—or prefers not to. They all appear to be undergoing different stages of a metamorphosis.

Kasper’s nickname is Xenos, outsider, stranger: to himself, and to writing. His story is reported through his teacher, who receives it in seemingly disconnected fragments: a 67-page letter, a book entitled The Logbook of a Swan Whisperer, sixteen 60-minute cassettes, sand. None of them hold any truth but complicate the jolted unfolding of the narrative: records, like the narrators in these pages, are unreliable, voicing erosion through time. The loci from which this story is written are not sites of stability, either. Kasper’s letter is sent from a hospital intensive care unit, Professor Van Niekerk writes from a shaken point of hesitancy. Out of such a condition of instability, of intensive care, the broken subjects in this tale of unwriting appear vulnerable: porous channels for quivering polyphonies, where every voice intimates that they’re using the tongue of another in an ongoing transmission whose origin is lost.

Broadcasting devices are also present—albeit fractured, partially erased—in the drawings by fellow South African William Kentridge interspersed in the pages of the Cahier. They point at the unpolished nature of transmission, and at the uncomfortable, damaged, violated site of writing. Erasure, in Kentridge’s abrupt brushstrokes, as much as in Kasper’s logbook entries, takes the form of black ink washes set against delicate calligraphy, or: the force of life and history as it interrupts and complicates polished forms of writing and reporting. What is testimony, what is transmitted and inevitably interfered with (because it is alive even when unspoken, silenced)?

Much in this story is unresolved, unexplained, untold. The actual documents are rarely disclosed and most of the narrative is half-guessed at or thwarted—and yet present on its own complicated terms.

Understanding does not come exclusively from texts as permanent marks: it is generated through listening on the periphery of canonical meaning, through speech that is sensuous, tactile like the ink, marks, and erasures of Kentridge’s drawings, or like the sand that the professor receives from her student by post. Speech prompts errors and astonishment, Kasper intimates while he morphs into a listening-speaking-writing enlandscaped entity beyond self. It must also voice absence, violence, and omission through dissonance. In this sense The Swan Whisperer is the necessary counterpart to Agaat/The Way of the Women, van Niekerk’s 2006 novel of inner polyphonies. While Agaat’s absorbing fullness, across more than 500 pages, overcomes the barriers of the narrator’s muteness with the noises of inner speech, The Swan Whisperer is a supreme synthesis of taciturn hints, its 37 pages alluding to records and reports where it’s never entirely certain who or what can be trusted, other than the materiality of words which demand to be heard and spoken. Agaat is a torrential unfolding of language in a multitude of selves and voices; The Swan Whisperer’s skeletal structure is that of a story within a story within a story told, mistold, spelled on the vapor on a windowpane only to disappear shortly after. Agaat is narrated by somebody who has lost her voice, is mute. The Swan Whisperer suggests we must make ourselves mute in our voices and adopt the voices of others, to enable a resounding flux of thinking-feeling to enter into writing. It does so by density rather than scale, disclosing connections in every word.

I can’t let go of The Swan Whisperer’s viscous materiality, its thick and fiery lava stream of correspondences drifting through my attention. It has the effect of a chant grasped beyond reasoning, an alchemic transformation that conveys dreamlike visions through a terse, poised language, in a disarming contrast of blurred states of mind and sharp rhetorical edges. At one point the professor encounters the phrase “tohoe wa bohoe” in Kasper’s logbook: first she dismisses it as nonsense, later she finds out that in Hebrew it means “formless void.” The appearance of Hebrew in Kasper’s undecipherable transcriptions seems to be a nod to the Enochian traditions of language divinely received, and to stories of angelic conversations. I begin to suspect every word is here for a reason, in a dizzying vertigo of connections and references that I’ve only begun to fathom, and that perhaps also includes all the numbers and the names precisely dotted all over these pages. The game of join-the-dots nevertheless leads to nothing: this story is not the clear outcome of a scheme or a hidden formula. The more I read it the more I sense, through its density and its frictions, that all its parts will never quite hinge, so close they are to the unruly tensions that exceed language and then claim to return to it in the most tangled arrangements. Through the filter of Kasper’s words and the Swan Whisperer’s spells the professor allows herself boldly and unapologetically to speak of magic and angels, as her character stages intermittent detachment and deep involvement with such entities, never apparently endorsed but certainly long frequented and deeply pondered. Perhaps this is what Kasper meant when he wrote that his story might be used for his teacher’s “dark designs.”

The text is punctuated with confrontations on writing, as the professor reports her discussions with Kasper, the conflicts between the roles of “an archivist” and “an aesthete,” between fact and fiction, the true and the beautiful. The breakthrough occurs when the tale ceases to preempt and critique itself, when its characters—and their readers—stop forcing themselves to understand. Kasper wants the Swan Whisperer to speak, as much as he wants himself to write, so he tries all the tricks, he tries to extract words by exposing him to terror, to the sublime, to romantic music. He even checks his mouth, and its ridges remind him of a harp—another Orphic symbol. He’s drawn to the Swan Whisperer’s ability to converse, although in another language: a skill he’s lost, and he can only regain, like Wordsworth’s boy, through learning to listen and to accept that taking part in a transmission means not always having control over it. He will begin to write when the recurring question, where does writing come from? is transformed into what and whom does writing come through?; when he is able to pass his experience onward, to someone else’s voice, no longer concerned with the choice between truth or fiction, but absorbed by the dissonance of their contrast. Kasper begins to write when he begins to care and to listen; when writing is no longer meant to be still, but is shaken by shivers of spoken words, sounds, relations, and rhythms. When are they heard, who or what whispers them to us, through us? Earlier in his story he had written, on a damp windowpane: “Perhaps my whisper was born before my lips”—a line from Osip Mandelstam, who once said that a poet is a stealer of air. Kasper breathes and writes through someone else’s words, maintaining that “we are here to be called to, to be called upon, to be summoned into existence.” This tale is not a beginning but a rebeginning, to borrow an expression coined by Laura Riding, who postulates that language is a gift to be given one another, in which and through which we disappear as singulars—like in Kasper’s final vision before vanishing, “a procession […] all of us connected at the wrist by an endless black ribbon.”

It ends with an incantation: Kasper’s swan song, or the mark of his metamorphosis into swan-as-sound that occurs through breath, in and out of language. In another chain of transformations Professor Van Niekerk becomes Kasper, Kasper becomes Xenos, writing as utterance is only possible for them as strangers in a language, when they cannot tread safely and must rely on sense and sound for tentative acts of connection, to reinstate their strangeness that will not allow itself to be erased. Like a magic spell, Kasper’s final words dictated through him by the Swan Whisperer and translated through the professor’s voice alter the common organization of sense, yet can neither be dismissed as nonsensical, marginal, nor pointless. Nor are they meant to lead to a higher understanding: they are very much of this world, because this world needs the awkward and the unpolished, the marginal and the unruly.

“I am still listening. I shall never stop listening. I could not discern the words of his poems, if that’s even what they were.” Such is Van Niekerk’s pronouncement as she listens to Kasper’s tapes in the final part of her account. In a moment of revelation that does not reveal anything but the endless questioning of speech and language, she realizes that “meaning is incidental. What matters are the material words.” And the transmissions that ensue. There is no origin, only an endless reworking, a fabulatory interweaving across the boundaries of language and through languages in the plural. Statements such as “I am the real dummy … and god only knows who is writing in me” testify to the moment when translation becomes transience. She reads Kasper’s words out loud, “in the hope that the water and the plumes will keep whispering them, perhaps whisper them through to him.” The landscape of language is both sensuous and psychological: Kasper’s poems in the tapes were “recorded near to running water or waving grass, […] to provide his voice with a kind of pedal point: not a bold bass pedal as in Bach, but rustling, murmuring, as though time were an instrument played by the transparent fingers of grass and water.” As I read these words I was reminded of the German term Stimmung, a tonality of being that conjoins subject and landscape; of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ inscape; of the Sybil’s leaves bearing their message in a flicker whose meaning exceeds trace or tangibility; of German sound artist Rolf Julius, who “wrote” a concert for a frozen lake, allowing his pared-down poetry and the surrounding landscape to become as much a part of the composition as the sounds; of Adriana Cavarero’s notion of chora, transmitted to her by Plato via Kristeva and expressed in her book For More than One Voice as the extra-linguistic, extra-conceptual quality of voice. I was reminded of Aristotle’s statement, “one must not learn, but suffer an emotion and be in a certain state.” I went back to David Toop’s Haunted Weather and its ruminations around secret sounds and states of becoming; to Emily Dickinson’s “being but an ear” marking the beat of her loss of sense and reason. I dwelled on the implications of my own choice, as a writer, to be a stranger in a second language—its discomforts, its thrills, the meddling with residues from another culture to form other sounds. Finally I recalled sentences by Clarice Lispector’s G.H. urging herself, from the edge of language and silence, to become “far-off landscape”: “Ah, but to reach muteness, what a great effort of voice.”

In only a handful of pages, The Swan Whisperer says a lot more about the ineffable yet material quality of listening, and its complex, necessary relation with cultural residues and language, than do most lengthy tomes. That a thirty-odd page text can disclose all this is extraordinary. That I haven’t yet quite worked out what exactly happens in the end will make for repeated reads that are certain to thicken, excite, and complicate my understanding. I shall say it again: The Swan Whisperer is not a text about writing, but a channel of transmission. It sounds a subtle onomatopoeia of the deep, of murmurs and silences, of the doing and undoing of meaning. Then writing re-begins.

The first of today’s choices is Marlene Van Niekerk’s The Swan Whisperer (translated by the author and Marius Swart), a short story of sorts in the form of a lecture. In her talk, Professor Van Niekerk, whether a real version or a fictional equivalent, tells her audience about a former student of hers, a man she decides to call ‘Kasper Olwagen’. After arranging for the hapless Kasper to go on a writing retreat in Amsterdam, the professor receives a lengthy letter in which he talks about his experiences in the Dutch capital – one which Van Niekerk promptly shoves in a drawer and forgets.

Eventually, however, she is drawn to returning to Kasper’s story despite herself, and it’s certainly worth reading. After a description of his new home, he turns to a new topic entirely, a homeless man he constantly sees around the Amsterdam canals. What draws the young writer’s attention is not so much the man himself as how he spends his days:

He straightened up, still murmuring, hands in the air like a conductor before the orchestra strikes up. Then he gave the first beat. And there, from under the bridge, swam two swans towards him, majestically, parading their necks, as if they belonged to him.

p.18 (Sylph Editions, 2015)

Back in South Africa, his teacher reads on incredulously – a homeless man who can control swans? It’s a lot better than Kasper’s previous efforts, at least…

The Swan Whisperer is an intriguing work, a text which swings between narrative and non-fiction, a little ambiguous in what it’s supposed to be. The writer deliberately distances us from the narrative, both through her sceptical attitude towards Kasper’s letter and her frequent returns to the language of her talk, addressing herself to her audience and at the same time dragging the reader away from Amsterdam. However, you sense that there’s a wider agenda here, with Van Niekerk (or her fictional alter-ego) gradually realising that there’s more to Kasper’s story than a cry for help from a homesick student. In a sense , she’s using the story to explore her own attitudes towards fiction, and how it should develop in South Africa.

By the end of the tale, the shift from a cynical academic reading a letter in the comfort of her home to a writer pursuing a new form of text is complete. Van Niekerk, having received cassettes of undecipherable murmurings from her former student (who has disappeared into the South African wilderness), now spends her time translating what she hears into a mix of Afrikaans and babble. Is it all fiction? Is it based on reality? Does it really matter? - tonysreadinglist.wordpress.com/2016/01/19/the-swan-whisperer-by-marlene-van-niekerk-translators-blues-by-franco-nasi-review/

Understanding does not come exclusively from texts as permanent marks: it is generated through listening on the periphery of canonical meaning, through speech that is sensuous, tactile like the ink, marks, and erasures of Kentridge’s drawings, or like the sand that the professor receives from her student by post. Speech prompts errors and astonishment, Kasper intimates while he morphs into a listening-speaking-writing enlandscaped entity beyond self. It must also voice absence, violence, and omission through dissonance. In this sense The Swan Whisperer is the necessary counterpart to Agaat/The Way of the Women, van Niekerk’s 2006 novel of inner polyphonies. While Agaat’s absorbing fullness, across more than 500 pages, overcomes the barriers of the narrator’s muteness with the noises of inner speech, The Swan Whisperer is a supreme synthesis of taciturn hints, its 37 pages alluding to records and reports where it’s never entirely certain who or what can be trusted, other than the materiality of words which demand to be heard and spoken. Agaat is a torrential unfolding of language in a multitude of selves and voices; The Swan Whisperer’s skeletal structure is that of a story within a story within a story told, mistold, spelled on the vapor on a windowpane only to disappear shortly after. Agaat is narrated by somebody who has lost her voice, is mute. The Swan Whisperer suggests we must make ourselves mute in our voices and adopt the voices of others, to enable a resounding flux of thinking-feeling to enter into writing. It does so by density rather than scale, disclosing connections in every word.

I can’t let go of The Swan Whisperer’s viscous materiality, its thick and fiery lava stream of correspondences drifting through my attention. It has the effect of a chant grasped beyond reasoning, an alchemic transformation that conveys dreamlike visions through a terse, poised language, in a disarming contrast of blurred states of mind and sharp rhetorical edges. At one point the professor encounters the phrase “tohoe wa bohoe” in Kasper’s logbook: first she dismisses it as nonsense, later she finds out that in Hebrew it means “formless void.” The appearance of Hebrew in Kasper’s undecipherable transcriptions seems to be a nod to the Enochian traditions of language divinely received, and to stories of angelic conversations. I begin to suspect every word is here for a reason, in a dizzying vertigo of connections and references that I’ve only begun to fathom, and that perhaps also includes all the numbers and the names precisely dotted all over these pages. The game of join-the-dots nevertheless leads to nothing: this story is not the clear outcome of a scheme or a hidden formula. The more I read it the more I sense, through its density and its frictions, that all its parts will never quite hinge, so close they are to the unruly tensions that exceed language and then claim to return to it in the most tangled arrangements. Through the filter of Kasper’s words and the Swan Whisperer’s spells the professor allows herself boldly and unapologetically to speak of magic and angels, as her character stages intermittent detachment and deep involvement with such entities, never apparently endorsed but certainly long frequented and deeply pondered. Perhaps this is what Kasper meant when he wrote that his story might be used for his teacher’s “dark designs.”

The text is punctuated with confrontations on writing, as the professor reports her discussions with Kasper, the conflicts between the roles of “an archivist” and “an aesthete,” between fact and fiction, the true and the beautiful. The breakthrough occurs when the tale ceases to preempt and critique itself, when its characters—and their readers—stop forcing themselves to understand. Kasper wants the Swan Whisperer to speak, as much as he wants himself to write, so he tries all the tricks, he tries to extract words by exposing him to terror, to the sublime, to romantic music. He even checks his mouth, and its ridges remind him of a harp—another Orphic symbol. He’s drawn to the Swan Whisperer’s ability to converse, although in another language: a skill he’s lost, and he can only regain, like Wordsworth’s boy, through learning to listen and to accept that taking part in a transmission means not always having control over it. He will begin to write when the recurring question, where does writing come from? is transformed into what and whom does writing come through?; when he is able to pass his experience onward, to someone else’s voice, no longer concerned with the choice between truth or fiction, but absorbed by the dissonance of their contrast. Kasper begins to write when he begins to care and to listen; when writing is no longer meant to be still, but is shaken by shivers of spoken words, sounds, relations, and rhythms. When are they heard, who or what whispers them to us, through us? Earlier in his story he had written, on a damp windowpane: “Perhaps my whisper was born before my lips”—a line from Osip Mandelstam, who once said that a poet is a stealer of air. Kasper breathes and writes through someone else’s words, maintaining that “we are here to be called to, to be called upon, to be summoned into existence.” This tale is not a beginning but a rebeginning, to borrow an expression coined by Laura Riding, who postulates that language is a gift to be given one another, in which and through which we disappear as singulars—like in Kasper’s final vision before vanishing, “a procession […] all of us connected at the wrist by an endless black ribbon.”

It ends with an incantation: Kasper’s swan song, or the mark of his metamorphosis into swan-as-sound that occurs through breath, in and out of language. In another chain of transformations Professor Van Niekerk becomes Kasper, Kasper becomes Xenos, writing as utterance is only possible for them as strangers in a language, when they cannot tread safely and must rely on sense and sound for tentative acts of connection, to reinstate their strangeness that will not allow itself to be erased. Like a magic spell, Kasper’s final words dictated through him by the Swan Whisperer and translated through the professor’s voice alter the common organization of sense, yet can neither be dismissed as nonsensical, marginal, nor pointless. Nor are they meant to lead to a higher understanding: they are very much of this world, because this world needs the awkward and the unpolished, the marginal and the unruly.

“I am still listening. I shall never stop listening. I could not discern the words of his poems, if that’s even what they were.” Such is Van Niekerk’s pronouncement as she listens to Kasper’s tapes in the final part of her account. In a moment of revelation that does not reveal anything but the endless questioning of speech and language, she realizes that “meaning is incidental. What matters are the material words.” And the transmissions that ensue. There is no origin, only an endless reworking, a fabulatory interweaving across the boundaries of language and through languages in the plural. Statements such as “I am the real dummy … and god only knows who is writing in me” testify to the moment when translation becomes transience. She reads Kasper’s words out loud, “in the hope that the water and the plumes will keep whispering them, perhaps whisper them through to him.” The landscape of language is both sensuous and psychological: Kasper’s poems in the tapes were “recorded near to running water or waving grass, […] to provide his voice with a kind of pedal point: not a bold bass pedal as in Bach, but rustling, murmuring, as though time were an instrument played by the transparent fingers of grass and water.” As I read these words I was reminded of the German term Stimmung, a tonality of being that conjoins subject and landscape; of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ inscape; of the Sybil’s leaves bearing their message in a flicker whose meaning exceeds trace or tangibility; of German sound artist Rolf Julius, who “wrote” a concert for a frozen lake, allowing his pared-down poetry and the surrounding landscape to become as much a part of the composition as the sounds; of Adriana Cavarero’s notion of chora, transmitted to her by Plato via Kristeva and expressed in her book For More than One Voice as the extra-linguistic, extra-conceptual quality of voice. I was reminded of Aristotle’s statement, “one must not learn, but suffer an emotion and be in a certain state.” I went back to David Toop’s Haunted Weather and its ruminations around secret sounds and states of becoming; to Emily Dickinson’s “being but an ear” marking the beat of her loss of sense and reason. I dwelled on the implications of my own choice, as a writer, to be a stranger in a second language—its discomforts, its thrills, the meddling with residues from another culture to form other sounds. Finally I recalled sentences by Clarice Lispector’s G.H. urging herself, from the edge of language and silence, to become “far-off landscape”: “Ah, but to reach muteness, what a great effort of voice.”

In only a handful of pages, The Swan Whisperer says a lot more about the ineffable yet material quality of listening, and its complex, necessary relation with cultural residues and language, than do most lengthy tomes. That a thirty-odd page text can disclose all this is extraordinary. That I haven’t yet quite worked out what exactly happens in the end will make for repeated reads that are certain to thicken, excite, and complicate my understanding. I shall say it again: The Swan Whisperer is not a text about writing, but a channel of transmission. It sounds a subtle onomatopoeia of the deep, of murmurs and silences, of the doing and undoing of meaning. Then writing re-begins.

Kasper’s initial struggle to “produce something tangible” is dissolved in the shimmer of his swan song. Read those words: if you try to decipher them you will no longer hear them or see them. Speak them out loud: maybe you will hear Kasper’s voice, Van Niekerk’s, and the Swan Whisperer’s. Maybe you’ll vanish in them too. - Daniela Cascella

The first of today’s choices is Marlene Van Niekerk’s The Swan Whisperer (translated by the author and Marius Swart), a short story of sorts in the form of a lecture. In her talk, Professor Van Niekerk, whether a real version or a fictional equivalent, tells her audience about a former student of hers, a man she decides to call ‘Kasper Olwagen’. After arranging for the hapless Kasper to go on a writing retreat in Amsterdam, the professor receives a lengthy letter in which he talks about his experiences in the Dutch capital – one which Van Niekerk promptly shoves in a drawer and forgets.

Eventually, however, she is drawn to returning to Kasper’s story despite herself, and it’s certainly worth reading. After a description of his new home, he turns to a new topic entirely, a homeless man he constantly sees around the Amsterdam canals. What draws the young writer’s attention is not so much the man himself as how he spends his days:

He straightened up, still murmuring, hands in the air like a conductor before the orchestra strikes up. Then he gave the first beat. And there, from under the bridge, swam two swans towards him, majestically, parading their necks, as if they belonged to him.

p.18 (Sylph Editions, 2015)

Back in South Africa, his teacher reads on incredulously – a homeless man who can control swans? It’s a lot better than Kasper’s previous efforts, at least…

The Swan Whisperer is an intriguing work, a text which swings between narrative and non-fiction, a little ambiguous in what it’s supposed to be. The writer deliberately distances us from the narrative, both through her sceptical attitude towards Kasper’s letter and her frequent returns to the language of her talk, addressing herself to her audience and at the same time dragging the reader away from Amsterdam. However, you sense that there’s a wider agenda here, with Van Niekerk (or her fictional alter-ego) gradually realising that there’s more to Kasper’s story than a cry for help from a homesick student. In a sense , she’s using the story to explore her own attitudes towards fiction, and how it should develop in South Africa.

By the end of the tale, the shift from a cynical academic reading a letter in the comfort of her home to a writer pursuing a new form of text is complete. Van Niekerk, having received cassettes of undecipherable murmurings from her former student (who has disappeared into the South African wilderness), now spends her time translating what she hears into a mix of Afrikaans and babble. Is it all fiction? Is it based on reality? Does it really matter? - tonysreadinglist.wordpress.com/2016/01/19/the-swan-whisperer-by-marlene-van-niekerk-translators-blues-by-franco-nasi-review/

Marlene van Niekerk, Agaat, Trans. by Michiel Heyns, Tin House Books, 2010.

Set in apartheid South Africa, Agaat portrays the unique relationship between Milla, a 67-year-old white woman, and her black maidservant turned caretaker, Agaat. Through flashbacks and diary entries, the reader learns about Milla's past. Life for white farmers in 1950s South Africa was full of promise — young and newly married, Milla raised a son and created her own farm out of a swathe of Cape mountainside. Forty years later her family has fallen apart, the country she knew is on the brink of huge change, and all she has left are memories and her proud, contrary, yet affectionate guardian. With haunting, lyrical prose, Marlene Van Niekerk creates a story of love and family loyalty. Winner of the South African Sunday Times Fiction Prize in 2007, Agaat was translated as The Way of the Women by Michiel Heyns, who received the Sol Plaatje Award for his translation.

"I was immediately mesmerized...Its beauty matches its depth and her achievement is as brilliant as it is haunting." - Toni Morrison

Few books I've read carry the visceral impact of Marlene van Niekerk's Agaat; it is the South African writer's second novel and fifth book, and it is stunning. Set in the apartheid era of the 1950s into the '90s, on a dairy farm contentiously run by a desperately unhappy white couple, Milla and Jak de Wet, and their half-adopted, half-enslaved black maid, Agaat, it is about institutional racial violence, intimate domestic violence, human violence against the natural world, pride, folly, self-deception, and the innately mixed, sometimes debased nature of human love. It is especially about how this mixed nature is expressed through the deep and complex language of the body; I don't believe I've ever read a book that so powerfully translates this physical language into printed words.

Agaat is narrated almost entirely by Milla, a strong-minded, verbally sophisticated, emotionally bereft Afrikaans woman paralyzed in old age by a motor-neuron disease, unable to communicate except with her eyes, and only then to Agaat, with whom she long had an anguished and loving bond and who cares for her on an all too intimate level. Here, for example, is Agaat cleaning Milla's mouth:

Say "ah" for doctor, says Agaat. I close my eyes. What have I done wrong? The little mole-hand nuzzles out my tongue. . . . The screw has squashed it in my mouth. My tongue is being staked out for its turn at ablution. The sponge is rough. With vigorous strokes my tongue is scrubbed down... Three times the sponge is recharged before Agaat is satisfied. My tongue feels eradicated. - Mary Gaitskill

Once in a great while, you read a novel that transforms you so completely you are sure the change must be obvious to all who know you. Like a trauma survivor, you are astonished when life continues all around you, oblivious to what you have just been through, absorbed in its old trivialities. Given my obsessions—race and racial politics; the delicate balance of power between servants and even the most benevolent employers—it is hard to imagine a novel more guaranteed to affect me than Marlene van Niekerk’s masterpiece, Agaat (trans. Michiel Heyns, Tin House Books, 2010; published in the UK as The Way of The Women, Jonathan Ball, 2006). The novel opens during the last days of apartheid and tells the story of an Afrikaner woman and the black servant who has worked for her for most of both their lives. But Agaat is a stunning feat for reasons that have nothing to do with my own particular background: structural intricacy, stylistic range, the daring and devastating allegory that underlies the narrative without overwhelming it. It may be unfashionable and imprudent to make such declarations in a review, but Agaat is, without a doubt, one of the five finest novels I have ever read, and one I will return to repeatedly, knowing that I will find new marvels within its pages on each reading.

The allegorical aspect is unsurprisingly the first to grab the reader’s attention, and so audacious is it, that one can scarcely outline it without making it seem ridiculous. It seems unlikely that any serious novelist could pull this off, and yet van Niekerk does: Milla, the Afrikaner woman and the novel’s narrator, is paralyzed and dying of Lou Gehrig’s disease, so that, as the apartheid era draws to its close around them, she must depend on her servant, Agaat, for all her needs. Agaat—whose right arm and hand are deformed, but who is adroit and capable despite this handicap—must wipe Milla’s backside, scratch her itches, massage spoonfuls of porridge down her throat, and guess her whims: her dying wish, for example, to look at the maps of her her farm, Grootmoedersdrift. Milla thinks:

I want to see the distances recorded and certified between the main road and the foot-hills, from the stables to the old orchard, I want to hook my eye to the little blue vein with the red bracket that marks the crossing, the bridge over the drift, the little arrow where the water of the drift wells up, the branchings of the river.

She wants, in short, to take stock one last time, to take ownership even briefly, even symbolically.

But Agaat had put away the maps of Grootmoedersdrift, along with various other documents and decorations, when Milla became bedridden and the back room of the farmhouse had to be cleared out for her. And now Agaat can only play twenty questions in response to Milla’s desperate eye signals:

Shall I draw the curtain a bit? Do you want to listen to the morning service? A tape? Wine women and song? The pan for number one? The pan for number two? Too cold? Too hot? Sit up straighter? Lie down flatter? Eat a bit more porridge? Fruit pulp? There is cold melon? With a bit of salt? Water? Tea with honey and lemon?

Whether she cannot or will not guess what Milla really wants, we ourselves must wonder, adjusting our perceptions through the course of the novel as the mystery of Agaat unfolds before us. For of course Agaat is wiser, and crueler, and more powerful than we have guessed at first, and though she never speaks for herself in the novel—we hear her words and see her actions only through Milla—we cannot help but share Milla’s suspicion that Agaat revels in her complete control over Milla’s body. She is the perfect nurse, following the doctor’s orders to the letter, foisting the prescribed exercises upon Milla’s unresisting limbs, studying her urine with a magnifying glass, meticulously recording “the motions of my entrances and my exits.” Will she eventually bring the maps out for Milla? This is the question that drives the third of the novel that takes place in the 1990s, and it is yet another choice to which summary cannot do justice: it seems an unlikely source of momentum until you actually find yourself turning the pages with bated breath, wondering how long Agaat will hold out, in what other ways she will misunderstand (or pretend to misunderstand) Milla’s longing before she yields.

The twenty chapters of Agaat are structured identically: each opens with Milla at Agaat’s mercy on her deathbed in the 1990s, then goes on to an extended flashback in the second person, then a dense stream-of-consciousness prose poem, and finally a entry or a series of entries from Milla’s diaries. But where this structure might have seemed arbitrary or contrived in the hands of a lesser writer, here it emerges organically from the novel’s context: the diary entries, for example, are there because Agaat is reading Milla’s diaries aloud to her to keep her entertained, and what an act of both devotion and defiance this is: against Milla’s wishes, Agaat has kept the diaries, and now, at the end of Milla’s life—when Milla can no longer speak for herself to question or to defend those earlier versions of herself—she has brought them out to share. What she herself thinks of the events and opinions revealed in the diaries we must piece together bit by bit as we learn more about her own place and history in the household.

As for the flashbacks, it seems natural, even necessary, for Milla to reminisce on her life as a farmer, beginning in 1946 when she becomes engaged to Jak de Wet and encompassing all the challenges and sorrows she endured in order to make a living off the land. After all, she has nothing but her mind, her memories. These flashbacks hint at the entire history of South Africa while gradually revealing the knotty secrets of Milla and Jak’s marriage and raising questions about Agaat’s complex role in the household: somewhere between friend and servant to Milla, despised and distrusted “woolly” to her embittered husband Jak, second mother to their son Jakkie. And while one might well expect to learn a great deal about farming—the symptoms of and treatments for botulism in cattle, the causes of pig measles, how to dose a poisoned bull—in these sections, there is also much unexpected beauty in the language and the imagery.

Van Niekerk has written two critically acclaimed novels so far, but she was first a poet, and in the prose poems that trace the progression of Milla’s illness from the initial appearance of symptoms to the moments before her death, she gives her poetic impulse free reign. The results are breathtaking, and not just because it is rare to encounter such prodigious gifts in a work of fiction:

…i clamp myself gather my waters my water-retaining clods my loam my shale i am fallow field but not decided by me who will gently plow me on contour plough in my stubbles and my devils’s thorn fertilise me with green manure and with straw to stiffen the wilt that this wilderness has brought on this bosom and brain? who blow into my nostrils with with breath of dark humus? who sow in me the strains of wheat named for daybreak or for hope? how will my belated harvest reflect and in what water? who will harvest who shear who share my fell my fleece my sheaf my small white pips? who will chew me until I bind for i have done as was done unto me the sickness belongs to us two.

What saves the novel from being an incoherent showcase of the author’s skills are the many brilliant resonances between the different sections: the subtle glint in one of the prose poems of an image we will later encounter in a flashback section, the spinning out in a diary entry of an event alluded to in a flashback, a small detail in a deathbed scene picked up in a flashback and turned into an answer to a question we didn’t know we had.

A concrete example to illustrate these abstractions: in a series of diary entries from 1960, we see Milla supervise Agaat’s first sheep-butchering lesson. Agaat is at the time twelve or thirteen, and it’s clear to us that some unspoken emotion simmers beneath her surface: perhaps disgust, perhaps just the fluctuating resentments of a girl that age. In the process of butchering the sheep, Agaat bloodies her dragging right sleeve. (Her clothes are all made with a longer right sleeve to conceal, by her own choice, the deformed arm.) When the butchering is over, Milla tells Agaat to wash up and orders another servant: “…go and fetch my old red jersey in the bedroom she can’t walk around any longer in that blood-stained thing.” But Agaat refuses to put on Milla’s red jersey. Milla reports Agaat’s response in her diary: “I have another jersey like this one she says where’s my jersey I want my own jersey it has the right sleeve.”

It is just another domestic detail in a long record of domestic details: Milla’s diaries abound with lists, plans, projects undertaken and unfinished. Easy enough to overlook or forget the red jersey, or to accept Agaat’s explanation for her refusal, for it is true that Milla’s red jersey does not have one longer sleeve. But the moment stuck, for some reason, in my mind—and sure enough, hundreds of pages later, the red jersey appears again, and the mystery of Agaat’s reluctance is solved for us, as are dozens of other little mysteries planted here and there (the silver bell Agaat brings Milla in her sickbed even though Milla is incapable of ringing it to summon her; the letterbox-style flap in the door of Agaat’s erstwhile bedroom) including many I am sure I overlooked on this first reading.

Any attentive reader will notice that the novel’s ingenious plotting relies on its architecture, its maze of secret passages and hidden entrances. (Though, at almost 600 pages, perhaps it is best compared to a doll’s house the size of a cathedral.) But as a writer—and one with a special interest in retrograde narration—I was floored by what van Niekerk does with these diary entries. The first ones we see are from 1960, and from there they continue chronologically until 1979, when Milla abandons her diary-keeping because her son is grown up and has left home to join the army; apparently she feels on some level that her primary domestic role has come to an end, and with it, the need to keep a record of it. Here—more than halfway through the book—Agaat begins to read out the packet of diaries that she has saved for last, but that in fact record the earliest events, beginning with her own arrival in the household in 1953 and her early relationship with Milla.

The purpose of telling a story backwards is of course that the reader already knows the ending, so that every event leading back from it is imbued with the weight of that ending: thus a glowing, hopeful beginning becomes a heartbreaking one if we already know that hope to be naïve or misplaced. This is abundantly true in Agaat; it is hard to imagine a more devastating ending than the beginning of Milla and Agaat’s journey together. But here this structure is not just an authorial imposition; it reveals Agaat’s own stake in the diary-reading, telling us that it is at least as painful for her to revisit the beginning of her life at Grootmoedersdrift as it is for Milla. When, at least, that beginning is laid out before us, it is not just the facts of it that take our breath away—although the final pieces of the puzzle we have been putting together for six hundred pages are immensely satisfying—but also our understanding of what it must mean for Agaat to read aloud the beginning and for Milla to hear it.

There are dissertations waiting to be written about Agaat, countless term papers on elements I will have to leave out in the interest of space here. Agaat’s white cap alone, that crowning symbol of her servanthood, deserves hours of analysis, as does the theme of embroidery in the novel, so effectively highlighted on the cover of the Tin House edition (the foreword to an Afrikaner embroidery handbook from the 1960s is, after all, one of the epigraphs to the novel).

But I cannot conclude this review without a word on the outstanding translation by Michiel Heyns. No, I don’t read Afrikaans, but one does not need to to recognise almost immediately that this translation is the work of a master. In his note, Heyns tells us: “Agaat is a highly allusive text, permeated, at times almost subliminally, with traces of Afrikaans cultural goods: songs, children’s rhymes, children’s games, hymns, idiomatic expressions, farming lore.” That he somehow manages to convey the spirit and the meaning of these allusions while preserving the foreign reader’s sense of being a stranger in a strange land is his genius. I could recognize the moments that would mean something different to a reader familiar with Afrikaner culture than they did to me, but what I felt was not exclusion, or frustration, or even resignation; Heyns’s windows into this text are made of glass. You put your fingers to them, feel that dry South African heat, and know that you are invited to look for as long you need to, to ponder and to make your own meaning. I now look forward to reading not only everything van Niekerk has written, but Heyns’s own work too, to experience more directly the powerful intelligence and sensitivity behind the English edition of Agaat. But first I must give my heart time to mend. I may have cried myself to sleep the night I finished Agaat, but I’m convinced I woke up already better and stronger. The best novels shatter your heart, but, to paraphrase Toni Morrison, they also gather up the pieces of you and give them back to you in all the right order. - Preeta Samarasan

The allegorical aspect is unsurprisingly the first to grab the reader’s attention, and so audacious is it, that one can scarcely outline it without making it seem ridiculous. It seems unlikely that any serious novelist could pull this off, and yet van Niekerk does: Milla, the Afrikaner woman and the novel’s narrator, is paralyzed and dying of Lou Gehrig’s disease, so that, as the apartheid era draws to its close around them, she must depend on her servant, Agaat, for all her needs. Agaat—whose right arm and hand are deformed, but who is adroit and capable despite this handicap—must wipe Milla’s backside, scratch her itches, massage spoonfuls of porridge down her throat, and guess her whims: her dying wish, for example, to look at the maps of her her farm, Grootmoedersdrift. Milla thinks:

I want to see the distances recorded and certified between the main road and the foot-hills, from the stables to the old orchard, I want to hook my eye to the little blue vein with the red bracket that marks the crossing, the bridge over the drift, the little arrow where the water of the drift wells up, the branchings of the river.

She wants, in short, to take stock one last time, to take ownership even briefly, even symbolically.

But Agaat had put away the maps of Grootmoedersdrift, along with various other documents and decorations, when Milla became bedridden and the back room of the farmhouse had to be cleared out for her. And now Agaat can only play twenty questions in response to Milla’s desperate eye signals:

Shall I draw the curtain a bit? Do you want to listen to the morning service? A tape? Wine women and song? The pan for number one? The pan for number two? Too cold? Too hot? Sit up straighter? Lie down flatter? Eat a bit more porridge? Fruit pulp? There is cold melon? With a bit of salt? Water? Tea with honey and lemon?

Whether she cannot or will not guess what Milla really wants, we ourselves must wonder, adjusting our perceptions through the course of the novel as the mystery of Agaat unfolds before us. For of course Agaat is wiser, and crueler, and more powerful than we have guessed at first, and though she never speaks for herself in the novel—we hear her words and see her actions only through Milla—we cannot help but share Milla’s suspicion that Agaat revels in her complete control over Milla’s body. She is the perfect nurse, following the doctor’s orders to the letter, foisting the prescribed exercises upon Milla’s unresisting limbs, studying her urine with a magnifying glass, meticulously recording “the motions of my entrances and my exits.” Will she eventually bring the maps out for Milla? This is the question that drives the third of the novel that takes place in the 1990s, and it is yet another choice to which summary cannot do justice: it seems an unlikely source of momentum until you actually find yourself turning the pages with bated breath, wondering how long Agaat will hold out, in what other ways she will misunderstand (or pretend to misunderstand) Milla’s longing before she yields.

The twenty chapters of Agaat are structured identically: each opens with Milla at Agaat’s mercy on her deathbed in the 1990s, then goes on to an extended flashback in the second person, then a dense stream-of-consciousness prose poem, and finally a entry or a series of entries from Milla’s diaries. But where this structure might have seemed arbitrary or contrived in the hands of a lesser writer, here it emerges organically from the novel’s context: the diary entries, for example, are there because Agaat is reading Milla’s diaries aloud to her to keep her entertained, and what an act of both devotion and defiance this is: against Milla’s wishes, Agaat has kept the diaries, and now, at the end of Milla’s life—when Milla can no longer speak for herself to question or to defend those earlier versions of herself—she has brought them out to share. What she herself thinks of the events and opinions revealed in the diaries we must piece together bit by bit as we learn more about her own place and history in the household.

As for the flashbacks, it seems natural, even necessary, for Milla to reminisce on her life as a farmer, beginning in 1946 when she becomes engaged to Jak de Wet and encompassing all the challenges and sorrows she endured in order to make a living off the land. After all, she has nothing but her mind, her memories. These flashbacks hint at the entire history of South Africa while gradually revealing the knotty secrets of Milla and Jak’s marriage and raising questions about Agaat’s complex role in the household: somewhere between friend and servant to Milla, despised and distrusted “woolly” to her embittered husband Jak, second mother to their son Jakkie. And while one might well expect to learn a great deal about farming—the symptoms of and treatments for botulism in cattle, the causes of pig measles, how to dose a poisoned bull—in these sections, there is also much unexpected beauty in the language and the imagery.

Van Niekerk has written two critically acclaimed novels so far, but she was first a poet, and in the prose poems that trace the progression of Milla’s illness from the initial appearance of symptoms to the moments before her death, she gives her poetic impulse free reign. The results are breathtaking, and not just because it is rare to encounter such prodigious gifts in a work of fiction:

…i clamp myself gather my waters my water-retaining clods my loam my shale i am fallow field but not decided by me who will gently plow me on contour plough in my stubbles and my devils’s thorn fertilise me with green manure and with straw to stiffen the wilt that this wilderness has brought on this bosom and brain? who blow into my nostrils with with breath of dark humus? who sow in me the strains of wheat named for daybreak or for hope? how will my belated harvest reflect and in what water? who will harvest who shear who share my fell my fleece my sheaf my small white pips? who will chew me until I bind for i have done as was done unto me the sickness belongs to us two.

What saves the novel from being an incoherent showcase of the author’s skills are the many brilliant resonances between the different sections: the subtle glint in one of the prose poems of an image we will later encounter in a flashback section, the spinning out in a diary entry of an event alluded to in a flashback, a small detail in a deathbed scene picked up in a flashback and turned into an answer to a question we didn’t know we had.

A concrete example to illustrate these abstractions: in a series of diary entries from 1960, we see Milla supervise Agaat’s first sheep-butchering lesson. Agaat is at the time twelve or thirteen, and it’s clear to us that some unspoken emotion simmers beneath her surface: perhaps disgust, perhaps just the fluctuating resentments of a girl that age. In the process of butchering the sheep, Agaat bloodies her dragging right sleeve. (Her clothes are all made with a longer right sleeve to conceal, by her own choice, the deformed arm.) When the butchering is over, Milla tells Agaat to wash up and orders another servant: “…go and fetch my old red jersey in the bedroom she can’t walk around any longer in that blood-stained thing.” But Agaat refuses to put on Milla’s red jersey. Milla reports Agaat’s response in her diary: “I have another jersey like this one she says where’s my jersey I want my own jersey it has the right sleeve.”

It is just another domestic detail in a long record of domestic details: Milla’s diaries abound with lists, plans, projects undertaken and unfinished. Easy enough to overlook or forget the red jersey, or to accept Agaat’s explanation for her refusal, for it is true that Milla’s red jersey does not have one longer sleeve. But the moment stuck, for some reason, in my mind—and sure enough, hundreds of pages later, the red jersey appears again, and the mystery of Agaat’s reluctance is solved for us, as are dozens of other little mysteries planted here and there (the silver bell Agaat brings Milla in her sickbed even though Milla is incapable of ringing it to summon her; the letterbox-style flap in the door of Agaat’s erstwhile bedroom) including many I am sure I overlooked on this first reading.

Any attentive reader will notice that the novel’s ingenious plotting relies on its architecture, its maze of secret passages and hidden entrances. (Though, at almost 600 pages, perhaps it is best compared to a doll’s house the size of a cathedral.) But as a writer—and one with a special interest in retrograde narration—I was floored by what van Niekerk does with these diary entries. The first ones we see are from 1960, and from there they continue chronologically until 1979, when Milla abandons her diary-keeping because her son is grown up and has left home to join the army; apparently she feels on some level that her primary domestic role has come to an end, and with it, the need to keep a record of it. Here—more than halfway through the book—Agaat begins to read out the packet of diaries that she has saved for last, but that in fact record the earliest events, beginning with her own arrival in the household in 1953 and her early relationship with Milla.

The purpose of telling a story backwards is of course that the reader already knows the ending, so that every event leading back from it is imbued with the weight of that ending: thus a glowing, hopeful beginning becomes a heartbreaking one if we already know that hope to be naïve or misplaced. This is abundantly true in Agaat; it is hard to imagine a more devastating ending than the beginning of Milla and Agaat’s journey together. But here this structure is not just an authorial imposition; it reveals Agaat’s own stake in the diary-reading, telling us that it is at least as painful for her to revisit the beginning of her life at Grootmoedersdrift as it is for Milla. When, at least, that beginning is laid out before us, it is not just the facts of it that take our breath away—although the final pieces of the puzzle we have been putting together for six hundred pages are immensely satisfying—but also our understanding of what it must mean for Agaat to read aloud the beginning and for Milla to hear it.

There are dissertations waiting to be written about Agaat, countless term papers on elements I will have to leave out in the interest of space here. Agaat’s white cap alone, that crowning symbol of her servanthood, deserves hours of analysis, as does the theme of embroidery in the novel, so effectively highlighted on the cover of the Tin House edition (the foreword to an Afrikaner embroidery handbook from the 1960s is, after all, one of the epigraphs to the novel).

But I cannot conclude this review without a word on the outstanding translation by Michiel Heyns. No, I don’t read Afrikaans, but one does not need to to recognise almost immediately that this translation is the work of a master. In his note, Heyns tells us: “Agaat is a highly allusive text, permeated, at times almost subliminally, with traces of Afrikaans cultural goods: songs, children’s rhymes, children’s games, hymns, idiomatic expressions, farming lore.” That he somehow manages to convey the spirit and the meaning of these allusions while preserving the foreign reader’s sense of being a stranger in a strange land is his genius. I could recognize the moments that would mean something different to a reader familiar with Afrikaner culture than they did to me, but what I felt was not exclusion, or frustration, or even resignation; Heyns’s windows into this text are made of glass. You put your fingers to them, feel that dry South African heat, and know that you are invited to look for as long you need to, to ponder and to make your own meaning. I now look forward to reading not only everything van Niekerk has written, but Heyns’s own work too, to experience more directly the powerful intelligence and sensitivity behind the English edition of Agaat. But first I must give my heart time to mend. I may have cried myself to sleep the night I finished Agaat, but I’m convinced I woke up already better and stronger. The best novels shatter your heart, but, to paraphrase Toni Morrison, they also gather up the pieces of you and give them back to you in all the right order. - Preeta Samarasan

In 1976, a 15-year-old boy named Jakkie de Wet comes home from boarding school at Easter to Grootmoedersdrift (Grandmother’s Crossing), the farm in the Cape Province of South Africa that has been in his mother’s family for generations. On such visits, Jakkie’s handsome, bullying father, Jak, usually drags the boy off on manly expeditions — hiking treacherous kloofs (ravines) and ridges, and scrabbling up (and falling off) rock faces — both to monopolize him and to vengefully deprive his mother, Milla, and his nanny, Agaat, of his company. The father is at war with both women; resentful of his wife’s sentimentality and agricultural know-how, and mistrustful of Agaat’s bond with his reticent son.

In 1976, a 15-year-old boy named Jakkie de Wet comes home from boarding school at Easter to Grootmoedersdrift (Grandmother’s Crossing), the farm in the Cape Province of South Africa that has been in his mother’s family for generations. On such visits, Jakkie’s handsome, bullying father, Jak, usually drags the boy off on manly expeditions — hiking treacherous kloofs (ravines) and ridges, and scrabbling up (and falling off) rock faces — both to monopolize him and to vengefully deprive his mother, Milla, and his nanny, Agaat, of his company. The father is at war with both women; resentful of his wife’s sentimentality and agricultural know-how, and mistrustful of Agaat’s bond with his reticent son.

To Jakkie, Agaat is second mother, confidante and almost-sister. To Milla, she is house servant, livestock expert and begrudged support — an almost-daughter in tidy apron and serving cap. Born in 1948, when Milla was 22, Agaat was the castoff child of laborers on Milla’s mother’s property, malnourished and barely clothed, with one good arm and one stunted one. When Milla first met her, she was called Asgat (Bottom-in-the-Ashes) because she crouched in the hearth of the hovel where she lived, a black Cinderella. Milla gave her a new name: Agaat (Dutch for Agatha, which means “good” in Greek) believing that “if you call things by their names, you have power over them.” She resolved to turn the girl into someone “sound and strong, grateful and ready to serve, a solid person who will make all my tears and misery worthwhile,” and brought her into her household. This was a compromised act of charity, if it was charity: the benefactress seeking too large a recompense for her generosity, too self-interested a cure for her loneliness. Milla’s husband protested her decision from the start. To Jak, Agaat was a “woolly,” a “hotnot” (an Afrikaans insult for a person of color) and a threat to the established social order. But in this, as in little else in her marriage, Milla insisted on her way.

On that 1976 Easter holiday, Agaat schemed with Jakkie so he could relax with his two mothers, “the white one and the brown one,” while his father stormed off to Luipaardskloof with his ropes and his rucksack. At the homestead, the three of them play Scrabble, building off one another’s words. When Agaat wins with “karooquickgrasses,” Jakkie challenges her, but Agaat finds the word in a well-thumbed copy of the Handbook for Farmers, and Milla supports her. “There’s more to a language than is written in a dictionary,” she tells her son. She knows this because Grootmoedersdrift holds many unofficial repositories of language. There are Milla’s diaries of her married life, written in Afrikaans in blue exercise notebooks “to get a grip on your times and days on Grootmoedersdrift, to scrunch up and make palpable the hours, the fleeting grain of things in your hastily scribbled sentences.” And there is Agaat herself. “She was a whole compilation of you, she contained you within her,” Milla thinks. “That was all that she could be, from the beginning. Your archive.”

Books like “Agaat,” the second novel by the South African writer Marlene van Niekerk, set in the last five decades of the departed century, are the reason people read novels, and the reason authors write them. It’s a monument to what the narrator calls “the compulsion to tell,” expressing truths that are too heartfelt, revelatory and damaging for proud people to speak aloud — or even to admit to themselves in private. Observed from the distance of time, they present a pattern of consoling completeness. Through incantatory visual and aural imagery (van Niekerk is a poet as well as a novelist), “Agaat” brings to life a landscape whose significance lies not only in its outward appearance (“deep kloofs overgrown with protected bush, the old avenue of wild figs next to the two-track road, . . . hills with plots of grass and soft brushwood for the sheep to overnight”) but in the inward imprint it has left on its inhabitants. How startling, how awe-inspiring, how necessary it is that the story van Niekerk assembles here is relayed by a woman who cannot speak.

The year is 1996, and Milla Redelinghuys de Wet, now 70, is in the final stages of A.L.S., “locked up in my own body,” dying in a bedroom at Grootmoedersdrift. Milla, speechless and bedridden, depends utterly on Agaat, as Agaat once depended on her. They communicate with their eyes, as they did from their earliest acquaintance. Agaat searches Milla’s blinks for signals, and interprets them as best she can: pain, hunger, sorrow, pique and, sometimes, irreverence. “That she can’t meet my every need, that she doesn’t know everything I think, that frustrates her beyond all measure,” Milla notices, still conscious, in her physical powerlessness, of her emotional power over her ward.

It is a complete reversal of their original roles. Yet Agaat misses very little. As she tends her afflicted mistress, she converses with her as if Milla’s interior monologue were audible. When Milla craves a bath, Agaat senses it, carries her into the tub on her back, and gets in with her, shoes and all, since there is no other way. And when Milla yearns to see a map of her property, pining (silently), “I want to see my ground, I want to see my land, even if only in outline, place names on a level surface. I want to send my eyes voyaging,” Agaat struggles to construe what it is her patient craves. “She wants to see something, something that’s outside and inside,” Agaat tells the doctor when he visits. He wonders if the nurse is losing her marbles, but Agaat persists until she cracks Milla’s code. “You can rest assured I won’t give up,” she tells her. “I don’t give up and you don’t give up. That’s our problem.”