Christopher Manson, Maze, Holt Paperbacks, 1985.

This is not really a book. This is a building in the shape of a book...a maze. Each numbered page depicts a room in the maze. Tempted? Test your wits against mine. I guarantee that my maze will challenge you to think in ways you've never thought before. But beware. One wrong turn and you may never escape!

Manson actually said that this book isn't really a book at all, but rather a building in the shape of a book. Intriguing, right?

Upon first glance, the gauntlet is thrown at the reader—“Solve The World’s Most Challenging Puzzle”—and believe me, the challenge is a lulu.

Each lovely page represents one room of a house that the player must navigate through to the center and back…in just 16 steps. Each numbered door on a page is a portal and some rooms lead to infinite loops while others will lead to dead-ends. Along the way, the reader is also challenged to discover an answer to a meta-puzzle.

The idea of a book acting as a labyrinth is a very cool one, and when it was originally published in 1985, a $10,000 prize was offered to the reader who could solve it the quickest. In 1988, 12 winners were chosen and they split the prize.

Since its publication, this book has spawned podcasts, clue websites and countless gallons of tears. I was fascinated with this book, but when I first got my copy, I succumbed to online message boards to help get me through it. It is absolutely ridiculous, the amount of work that people have gone through to solve this puzzle in different ways. My hat is off to them, but I just wish that I could look at Maze again with fresh eyes.

And now is your chance to journey into the maze. To help you out, I offer to you some spoilers...not that I'd use them or anything. -

https://boingboing.net/2015/07/27/escaping-the-maze.html

This is not one of those pencil mazes you worked on as a kid. The entire book is one addictive maze. Each page spread is a room leading to other page/rooms. Your goal is to find the shortest route to the center and back while solving the puzzle in the center room--if you can figure out what the puzzle is. But then, each room is a puzzle filled with clues to decipher. Read the text and examine the gorgeous illustrations carefully. Beware--not every clue can be trusted. If you're an online gamer, consider this a Web site you can carry wherever you go.

When I was a child, I was given a book that was not really a book at all.

It tricked me at first. I believed anything with pages to turn, words, and pictures was a book, but as I turned this object’s pages, read its words, looked at its pictures, I felt myself in the presence of something fantastically different than the other books scattered throughout the house. In a book, I began at page one, moved to page two, and by this way eventually found myself at the end. No matter what occurred on the pages, if I kept reading I would eventually reach the final sentence, whether I wanted to or not. The thing disguised as a book, on the other hand, did not take me from page one to page two. “This is a building in the shape of a book,” it said. It elaborated, told me it was a maze and that by traveling through the rooms I might find my way to the center. Clues lay hidden in each room to suggest where to go next. Not all the clues were going to help me. Some would try and get me terribly lost. Unnerving as this was, it was also irresistible, and I spent many hours on my stomach, the maze before me on the carpet, as I wandered through the rooms, trying (unsuccessfully) to untangle the clues, and continually opening a door leading to a room that was pitch black except for the dozens of eyes staring at me. A room where I died over and over and over and over and over again.

The title of this work that consumed large chunks of my childhood is MAZE (with the flavorless subtitle, Solve the World’s Most Challenging Puzzle). It is one of a handful of works written and illustrated by Christopher Manson, and though his others are similar in their use of fairy tale and mythic elements, MAZE alone possess a hypnotic power, transcending its binding and reaching toward something else.

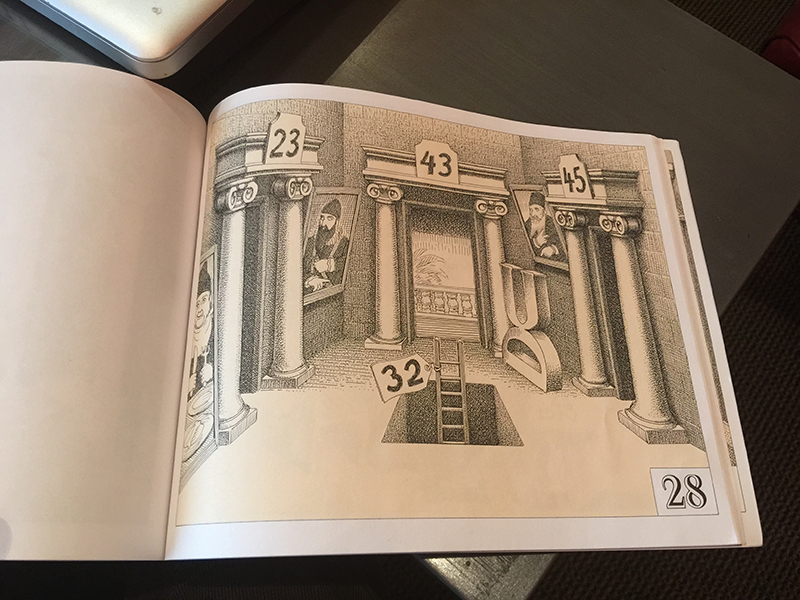

Each double-page spread depicts one of MAZE’s 45 rooms. The left page contains between seven and thirteen lines of text while the right page features a lush pen-and-ink drawing of the room itself, eerie as a de Chirico with its impression that either someone has just left or will shortly arrive. Manson loosed his prodigious imagination in the creation of these spaces, crafting each room with a general theme and them cramming most of them with a mix of baroque furniture, shrubs manicured into geometric shapes, exotic birds, Kafkaesque machines, musical instruments, trap doors, lamps, crumbling porticos, strange glyphs and signs carved into the walls. Or, instead, a room may be empty except for a fire raging inside a hearth whose cavernous depths are crowned by mantle carved to look like a gaping mouth. Inside each room are doors, and each door will take you to another room. You are challenged to find a way to room 45 and then back to room 1 using the fewest steps possible. Furthermore, a riddle is hidden in room 45, and the riddle’s solution is tucked away in the other 44 rooms.

What sounds simple at first becomes morbidly, maddeningly difficult. Rather than not having enough information, the challenge becomes one of over-saturation as each elaborately arranged room and block of narrative text provides numerous pointing fingers (sometimes literally) without there being indications as to which are more valuable than others. Will the solution to a particular room become clear only after you turn the room upside down? Is a face hidden in the carving over the door? Should you rearrange the letters in words spoken by the characters? As you move from room to room you find yourself going in circles, collapsing back into already experienced scenes, and you can’t help but wonder, as though this were really a book by Robbe-Grillet, whether or not something obscure but crucial has changed.

Of course, things have changed. As you reenter a previous room, the returning images—an umbrella leaning against a doorway or the shadow cast by a bowling pin—become new in light of something else recently seen. Each room builds on your lexicon of figures, signs, and your MAZE language. Your perception deepens, and so, to adapt the Zen koan, you never enter the same room twice.

In the attempt to unravel MAZE’s devilishly hidden secrets, a possible solution something greater presents itself. If we can take something away from this work—other than an appreciation for cross-hatch shading technique and unsettling dialogue—it is the idea of repetition as a path towards sublimity.

Our lives are, it seems, composed of a few recurring acts and motions, such as making dinner and falling in love. Once these repetitions are noticed, it can become difficult to see anything but constantly overlapping patterns tying your birth and death together in a bow. The patterns become avenues towards disquiet, the sense that we are now and will always be stamping over the same worn ground. And this is true. We are now and will always be stamping over the same worn ground.

MAZE’s major triumph lies in urging us to recognize the inexorability of continual repetition, something that becomes even more crucial in our increasingly labyrinthine world. We live with the expanding illusion of different and unique rooms, each seeming to offer momentary justification for our existence. We bound through chambers of experiences and believe ourselves to be continually ascending towards…what? Enlightenment? God? A consciousness-shattering orgasm? But the elaborate approaches to fundamental anxieties are not new rooms so much as rearranged furniture. The rooms are the same, a fact we don’t realize until we suddenly recognize our surroundings and think, “how is it possible I am still here dealing with this?” We hold the proof of our varied and wild experience, but proof does not equate with meaning, and the awareness that our hands are gripping shrinking fistfuls of sand begins to feel like the darkest moment of our lives.

MAZE recognizes our learned desire to progress and then creates an environment where such progress is almost impossible. “You haven’t spend nearly enough time here,” MAZE seems to say, “keep looking.” At first this can seem like a punishment. We want to move upwards and onwards! How dare someone deprive us of our right to ascend! But, and this is a beauty of the printed page, MAZE does not respond to our rage. It sits patiently on the shelf until our curiosity bests our petulance and we take it down again. Then it continues from where we left off: at room number 1.

Of course, the 31 years since the book’s publication gave people a chance to solve most—I hesitate to say all—of MAZE’s puzzles. If you want, you can simply Google the answer. You will find websites and podcasts dedicated to MAZE exegesis and emulation, where fans of the work debate the meaning of symbols drawn on a scroll or the importance of an apple partially hidden in shadows. They will also tell you the identity of the narrator and how to reach room 45. However, I will caution you: knowing the solution to the riddle or the shortest path through MAZE will not unlock the secret of the work. That can only happen by accepting the puzzle as it presents itself, in all its opacity, in all of its chaos. Anything less is—to use a key MAZE theme—a red herring. You may think you’ve reached the center, but in reality you will have only skirted around the outer rim, never allowing yourself to be swallowed whole.

I have never reached the 45th room, which means I am always starting and continuing through MAZE. I’ve stopped expecting I’ll find the shortest route, and I can’t even think about solving the riddle. Now I enter primarily to breathe the strangeness of the spaces and to show friends who haven’t ever heard of MAZE: Solve the World’s Most Challenging Puzzle. Because I always follow the rules and enter with disbelief suspended there are several rooms I haven’t ever seen. I’m sure I’m missing something obvious, and maybe this should bother me, but I am content to wander through the rooms whose surroundings I recognize and provide continual delight. In room 7 an abandoned toy duck looks up at me. In room 20 a tortoise crawls across the carpet. In room 26 several devils perform a play. In room 42 a small bear holds a sign reading “saints that way sinners this way.” And in room 45? That’s something you’ll have to find out on your own. - Samuel Annis

“This is not really a book. This is a

building in the shape of a book… a maze.” —From the directions

to Maze, by Christopher Manson

I first read Maze as a child, on a bus.

I don’t remember where the bus was going (I’m not even sure it

was a bus — maybe it was a van?) because I was thoroughly and

instantly inside the book. From the first page, I felt stifled and

scared, full of an obsessive drive that I otherwise only associate

with moments of sexual awakening. The words of the directions

functioned like a spell. The book told me that it was a building, and

then it was. And I was trapped inside.

Maze, published in 1985 with the

tagline “Solve the World’s Most Challenging Puzzle,” was part

of a mini trend of picture puzzle books with real cash prizes,

patterned after 1979’s Masquerade. But where Masquerade was dreamy,

off kilter, alarming — it seemed to open up somehow to the

possibilities of a world of mystery — Maze made me feel like I

was sneaking off to read porn. It was like disappearing into a hole.

The rules are simple. Each page,

numbered 1 through 45, is a room in the Maze. Each room has numbered

doors that lead to other rooms. To go through a door, you turn to the

indicated page, where you will be faced with another room full of

doors and mysterious objects, depicted in Manson’s architectural

black and white engravings. Your aim is to reach the center (room

45), and then escape back out to room one, in no more than sixteen

steps.

When I started work on this article, I

was reluctant to pick up the book again, even though I’d remembered

it with intense emotion for decades. But Maze was memorable because

it was unpleasant, like a drug that shows you the places where your

brain can break. I’d spent what felt like days at a time dissecting

its images and mapping its paths, getting stuck in its loops and

traps, wanting to quit but unable to put the book down until I opened

one more door, tried one more path. Rooms leading into rooms, a

secret that you are trying to uncover, a chase. A sense of

fascination that makes it difficult to lift your eyes or leave your

house.

The truth is, I feel the way Maze made

me feel all the time now. The big difference between reading it and

wandering through the endless rooms of the internet is that with

Maze, we are assured that there is a solution. There is an escape.

There is even — if we are especially clever and worthy — a

meaning.

With “Maze,” we are assured that

there is a solution. There is an escape. There is even — if we

are especially clever and worthy — a meaning.

Because the maze doesn’t just have a

solution—it also has an answer. There is a riddle hidden in room

45, with the answer concealed somewhere along the shortest path. And

this answer was valuable, not just because of how well it was

guarded, but in the grossest commercial terms. Like the riddle of the

Sphinx, it had multiple rewards. A publicity campaign offered a ten

thousand dollar prize to the first person who could provide all three

parts of the solution, but by the time I got my hands on the book,

the campaign had concluded. - Reina Hardy

At a local gathering of friends the other day, the classic puzzle book Maze, by Christopher Manson, came up in conversation. Many, myself included, recalled encountering it not too long after its original 1985 publication date. At the time, we all found it a fascinating artifact, though a completely inscrutable puzzle.

The book is still for sale, as it turns out, and there's also an online, hypertext version of the book you can wander through freely. (I note that the website appears to reside among the archives of an early electronic-publishing venture, and has remained unmodified since the mid-1990s. Sadly, the scanned illustrations are formatted to fit the relatively dinky computer displays of that era, resulting in much of the fine detail getting lost. I suppose I should encourage you to go buy the book, if you find them sufficiently intriguing.)

After I returned home that evening, it occurred to me that I probably hadn't thought much about Maze since the ascent of Wikipedia, and surely it spelled out the solution. Why, yes. And what a solution! It's amusing I can look at this more than 20 years after the book's original publication and tell you why this would get razzed by any of the hardcore puzzle people I know today.

Granted, it was supposed to be very hard, because there was a cash-money prize for the first correct response. But the Wikipedia article implies that they overdid it, since the publishers extended the deadline at least once, and it's unclear if any claim was ever made. And no wonder, really; the solution demands you selectively perform wordplay on picture and text elements along the path, but gives you no clues as to which elements are important, and what should be done with them.

For example (and I'm about to get a little spoilery here) on this page, it happens that you're supposed to get a word by taking two picture elements and anagramming them together. But for all you know, maybe you combine the A with BELL and perform a sound-alike wordplay to get ABLE. Or perhaps the word is simply BELL, after all. Or a dozen other things suggested by the image. They all seem equally right - which is to say, none especially so.

Carry this feeling over the path's 16 pages, and I assert you've got an utterly unsolvable combinatorial explosion. I would be quite interested to learn of integral clues I'm overlooking, though, or to hear about someone who solved the book without any hints! Until then, I must conclude that for all the book's beauty - and it is quite a lovely thing to flip through - as a puzzle, it would get booed off the stage at the MIT mystery hunt.

More important than its puzzle, however, is the book's legacy. Without a doubt, the book left a lasting inspiration to many, stoking a hunger to try solving more baroque and beautiful puzzles, even if that means having to create them first. You can see echoes of Maze in art-heavy digital adventures such as Myst. In fact, the stimulus for this group recollection among friends was a new puzzle designed with Maze in mind, by Gameshelf pal Andrew Plotkin. I have it on good authority that it was cracked by dedicated solvers within a day. - Jason McIntosh

http://gameshelf.jmac.org/2008/03/maze-beautiful-inspirational-u/

Maze by Christopher Manson is, according to the cover, “The World’s Most Challenging Puzzle”. True to the claim, nobody correctly solved it during the two years between publication in October 1985 and the close of the competition in September 1987. The $10,000 prize money was instead split between several people who all got closest to the solution.

The puzzle has several parts. The first step is to find the shortest path in and out of the maze. Then there is a cryptic riddle to find at the centre of the maze. Finally, the solution to the riddle is solved by finding clues hidden along the shortest path.

This post takes a quick look at the book and provides the solution to finding the shortest path. You can also download an interactive map that keen Maze-solvers may find useful.

Maze is a picture book and the maze is made up of 45 numbered rooms drawn in black-and-white hatching. The style will either be to your taste or not. For me, the random contents and varied perspectives in each room are the draw rather than the artwork.

Each room has numbered doors leading out of it. The idea is that you choose a door and turn to the appropriately numbered page in order to move around the maze. Every page tells a different piece of a story of a group of people being led through the maze by a cruel guide. By following the maze from room to room you get to choose your own adventure. The story is more enigmatic than exciting or interesting and serves primarily to provide clues.

One trick to the Maze is that many of the doors do not have numbers on them. These un-numbered doors represent paths that lead into that room, but not out: the doors are one-way only. There are a few hints to this through the book. Sometimes the story confirms that rooms with only one numbered door have only a single way out, for example. There is even one dead end with no way out at all and a blackly humourous ending to the story.

The shortest path through the maze takes 16 steps leading from Room 1, to the “centre” of the maze in Room 45, and back to Room 1. The one-way doors mean that getting out of the maze once you’ve got to the centre is not simply a case of retracing your steps.

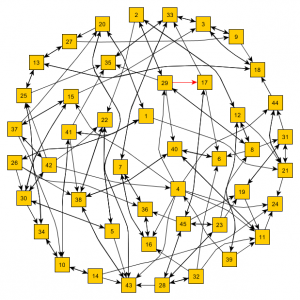

One way to find your way through the maze is to find the clues on each page that tell you which way to go next. Many of these clues are so frustratingly cryptic that I took a different approach. I chose to map out the entire book in a free program called yEd Graph Editor. You can download it here. You can draw the whole maze out by hand, but you’ll soon have lines criss-crossing confusingly all over the place and its easy to miss some important features of the maze.

Click on the image to open the full size version of the map. The source file, in graphml format, can be downloaded here (right click and save). Play around with it and rearrange the rooms to your satisfaction!

Mapping out the room was an interesting exercise and revealed a couple of important things. At first glance, there is no way to get from Room 1 to Room 45. The maze appears unsolvable.

However, the second important clue is that the number of paths leading into or out of each room is equal to the number of doors, except in one case. Room 17 has four doors but, on first glance there only three paths that lead in or out of it. The unnumbered door in Room 17 is a secret entrance and only by finding it can you reach Room 45.

Carefully scouring every page reveals that there is a door numbered 17 hidden in Room 29. This is beautifully concealed with a perspective trick, and signposted in several other ways. I’ve marked the hidden door from Room 29 to Room 17 with a red arrow in my map.

There is also an extra door in Room 39. However, this door is bricked up with a giant Jester’s hat over the top of. To me, this is a pretty clear hint that this is not a real door.

Having mapped the whole maze, yEd Graph Editor has a couple of useful features for quickly finding the shortest path. You can click on any “node” and see its “successors” in a giant chain.

First, you can select Room 1 and quickly trace a path from there to Room 26, to 30, 42, 4, 29, through the secret door to 17, then finally to Room 45. That’s Room 1 to Room 45 in 7 steps.

read more here

“This site is devoted to the genre of the immersive puzzle,

to the brilliance of Christopher Manson, who, in one stroke

launched and mastered a new genre of literature.” - White Raven

“This is not really a book. This is a building in the shape of a book…a Maze. Each numbered page depicts a room in the maze.” “Test your wits against mine. I guarantee that my maze will challenge you to think in ways you’ve never thought before. But beware…one wrong turn and you may never escape!”- From MAZE, Copyright 1985.

In 1985 Christopher Manson’s “MAZE: Solve the World’s Most Challenging Puzzle” was released and took the nation by storm. It was, most likely, the world’s most popular visual puzzle until the computer game MYST was released in 1993 which was based on the MAZE archetype. MAZE was also the first of a new genre of puzzle, the immersive visual puzzle. Paving the way for games such as MYST, Tomb Raider and Portal.

MAZE is a picture book filled with 45 black and white hand drawn rooms. On the facing page is a conversation between the visitors and the guide. Each room, and the bit of conversation that goes with it, contains several puzzles. Sometimes the puzzle indicates the correct door to take. At other times that you have taken a wrong turn, or that all hope is lost.

MAZE is “played” by turning to the page number indicated on the door to pass through that door. Despite having only 45 rooms, the number of connections between the rooms makes mapping MAZE practically impossible. The structure of the maze is multi-goal, non-continuous, overlapping, objective, static, and conceptual (see Maze Theory).

But mapping the MAZE is peanuts compared to the puzzles. Solving more than a handful of the puzzles is monumentally difficult. Mr. Manson’s MAZE, true to its title, is probably the world’s most difficult puzzle. The subtlety depth and variety of the puzzles is incredible. Mr. Manson made use of every basic form of puzzle available (see Puzzle Theory), and he invented several sub-types.

MAZE contains an astonishing number of puzzles, more than 116. Of these 116+ puzzles the solution for only 21 are presently available online. I say we change that…

Welcome to the conversation.- Images and quoted text copyright 1985 by Christopher Manson

The Story of MAZE: Solve the World’s Most Challenging Puzzle

Written by White Raven with information provided by Christopher Manson

One more cup of coffee…

It was 1984 and Christopher Manson was up late, 2 AM, scribbling and thinking. Recovering from Saturday night he was downing cups of coffee and wracking his brain for a book idea.

Manson had just finished illustrating a cookbook for a friend of his. At the meeting with the publisher he asked about possible work opportunities. The publisher had none and instead urged Manson to come up with a book idea and pitch it to him. Manson was living day to day out of a small apartment, and his bank account was near zero. And so he was up at 2 AM with nothing to show for it.

He decided to call it night but then changed his mind, “Just one more cup of coffee.” And one more cup was all it took. Over the next 45 minutes MAZE was born, the ideas tumbling out onto paper.

Where the inspiration came from, Manson says, is a thing of mystery, bits borrowed from countless sources and experiences. None the less, he was able to highlight a few specific influences. Most obvious is Manson’s interest in architecture, as displayed in the wide variety of architectural styles represented in the rooms. Manson’s love of classic science fiction, Jules Verne’s “Mysterious Island” in particular, informed the tone and general sense of wonder and disquiet. While Manson’s appetite for alchemic illustrations, forgotten books and obscure writings, supplied much of the puzzle content.

MAZE is a picture book filled with 45 black and white hand drawn rooms. On the facing page is a conversation between the visitors and the guide. Each room, and the bit of conversation that goes with it, contains several puzzles. Sometimes the puzzle indicates the correct door to take. At other times that you have taken a wrong turn, or that all hope is lost.

MAZE is “played” by turning to the page number indicated on the door to pass through that door. Despite having only 45 rooms, the number of connections between the rooms makes mapping MAZE practically impossible. The structure of the maze is multi-goal, non-continuous, overlapping, objective, static, and conceptual (see Maze Theory).

But mapping the MAZE is peanuts compared to the puzzles. Solving more than a handful of the puzzles is monumentally difficult. Mr. Manson’s MAZE, true to its title, is probably the world’s most difficult puzzle. The subtlety depth and variety of the puzzles is incredible. Mr. Manson made use of every basic form of puzzle available (see Puzzle Theory), and he invented several sub-types.

MAZE contains an astonishing number of puzzles, more than 116. Of these 116+ puzzles the solution for only 21 are presently available online. I say we change that…

Welcome to the conversation.- Images and quoted text copyright 1985 by Christopher Manson

The Story of MAZE: Solve the World’s Most Challenging Puzzle

Written by White Raven with information provided by Christopher Manson

One more cup of coffee…

It was 1984 and Christopher Manson was up late, 2 AM, scribbling and thinking. Recovering from Saturday night he was downing cups of coffee and wracking his brain for a book idea.

Manson had just finished illustrating a cookbook for a friend of his. At the meeting with the publisher he asked about possible work opportunities. The publisher had none and instead urged Manson to come up with a book idea and pitch it to him. Manson was living day to day out of a small apartment, and his bank account was near zero. And so he was up at 2 AM with nothing to show for it.

He decided to call it night but then changed his mind, “Just one more cup of coffee.” And one more cup was all it took. Over the next 45 minutes MAZE was born, the ideas tumbling out onto paper.

Where the inspiration came from, Manson says, is a thing of mystery, bits borrowed from countless sources and experiences. None the less, he was able to highlight a few specific influences. Most obvious is Manson’s interest in architecture, as displayed in the wide variety of architectural styles represented in the rooms. Manson’s love of classic science fiction, Jules Verne’s “Mysterious Island” in particular, informed the tone and general sense of wonder and disquiet. While Manson’s appetite for alchemic illustrations, forgotten books and obscure writings, supplied much of the puzzle content.

When he presented the idea to his friend’s publisher, the publisher wasn’t sure what to do with it and referred Manson to someone at Henry Holt & Company for a recommendation. Instead of a recommendation the publisher at Henry Holt was immediately sold on the idea and gave Manson an advance…and a deadline.

Over the next 9 months Manson lived off of the advance and churned out the work. After working out the main puzzle he focused on building hints and false leads. He rarely left his apartment. Day after day, he drew the painstakingly detailed inked illustrations from morning to night. The mail piled up. His hands ached and began to cramp. Toward the end he was soaking his hands in warm water several times a day to ward off cramping.

The Prize…

Manson did not make the book with a contest in mind, the prize was the publisher’s idea, as was the cover style and title. A law firm was hired by the publisher to manage the contest. Manson wanted to call it “Labyrinth” but the publisher objected due to the Jim Henson movie by that name released just months before.

Manson was unaware of the deep cord that the book struck with people in America and Britain, and the frenzy surrounding the contest. He was, however, relieved to finally have an income.

Manson had intended MAZE to be extremely difficult, but still he was surprised when the deadline came and went with no one even close to a solution. The deadline was extended and clues to the puzzle in room 45 were released by the publisher. Then the next deadline came around still no one had the solution. In the end the prize money was divided between the 10 people determined to be the closest. All ten had significant portions of the solution worked out, but no one had a winning keyword.

Over the next 9 months Manson lived off of the advance and churned out the work. After working out the main puzzle he focused on building hints and false leads. He rarely left his apartment. Day after day, he drew the painstakingly detailed inked illustrations from morning to night. The mail piled up. His hands ached and began to cramp. Toward the end he was soaking his hands in warm water several times a day to ward off cramping.

The Prize…

Manson did not make the book with a contest in mind, the prize was the publisher’s idea, as was the cover style and title. A law firm was hired by the publisher to manage the contest. Manson wanted to call it “Labyrinth” but the publisher objected due to the Jim Henson movie by that name released just months before.

Manson was unaware of the deep cord that the book struck with people in America and Britain, and the frenzy surrounding the contest. He was, however, relieved to finally have an income.

Manson had intended MAZE to be extremely difficult, but still he was surprised when the deadline came and went with no one even close to a solution. The deadline was extended and clues to the puzzle in room 45 were released by the publisher. Then the next deadline came around still no one had the solution. In the end the prize money was divided between the 10 people determined to be the closest. All ten had significant portions of the solution worked out, but no one had a winning keyword.

The Video Game…

Among other things, Manson does book restoration the Library of Congress, he lives neck deep in rare and obscure books. He is a master of pen and paper, wood block and printing press, historical ephemera and long forgotten lore. As such, his contact with computers is rather limited but he knew a little about the computer game.

In 1994 Interplay released a colorized version of MAZE with hyperlinks leading from room to room. Manson was invited to meet with the game developer, who was dealing with a serious back injury and had trouble focusing. Afterwards Manson was given a CD with the game on it and was impressed with the result, but the last Manson had heard the game idea has been dropped…he was surprised to learn that it had been produced and sold as “Riddle of the Maze” for Macintosh.

Another computer graphics version of the book began to be produced but was dropped before completion. Manson was not aware of this version and perhaps was not ever told of it since development does not appear to have gotten very far past conception. The images of this version are striking on account of the extreme lighting effects and the fact that they are only loosely based on Manson’s drawings. It is probably fortunate that this version was not produced since the content of the rooms is very altered, destroying the dearth of puzzles scattered throughout MAZE.

Legacy…

The Henry Holt was originally interested in a sequel. Manson showed them drawings of rooms and plans for a 100 room labyrinth. Despite considerable enthusiasm from fans – many saying it was their favorite book ever – Henry Holt backed away. “They were going through a reorganization, they were distracted,” Manson recalled, “I feel I should have pushed harder.”

In 1999 the computer game MYST became the top selling video game in history. The developers of the game reference Jules Verne’s “Mysterious Island” as the source of their inspiration, (the same book which inspired MAZE) but for obvious reasons a great many MYST and MAZE fans suspect that MAZE was a central source of inspiration as well.

In the words of one fan, “More important than its puzzle, however, is the book’s legacy. Without a doubt, the book left a lasting inspiration to many, stoking a hunger to try solving more baroque and beautiful puzzles, even if that means having to create them first. You can see echoes of Maze in art-heavy digital adventures such as Myst.” – Jason McIntosh from his blog entry “Maze: beautiful, inspirational, unsolvable.”

Another more recent child of MAZE is the acclaimed 2000 bestseller “House of Leaves” by Mark Z. Danielewski. The book stars a person falling into madness from reading a book about a movie about a shape shifting maze within a house, and the people stupid enough to venture inside.

With the rise of computer gaming, MAZE went out of print briefly, but growing interest (especially evident in internet chat rooms) brought the book back. Praise from sites all over internet attest to the book’s enduring power:

“My GODS people, this book is insane. I’ve owned it for two years now. Why haven’t I gotten around to writing a review yet? BECAUSE I’VE BEEN WORKING ON IT THIS WHOLE TIME. MADNESS!!!!!” – Jesse Nelson

“Good grief. This book will be the death of me. I found it years ago, still haven’t solved it, and sometimes it feels like the book isn’t even real – like I spookily stumbled across the only copy that changes as I am reading it. I have never even seen this book anywhere except for the one store I bought it from. I’m pretty sure Manson is the devil, or God, for creating a book this crazy. Good luck to you if you decide to journey down this path to madness!”- Laura

“This work is an engrossing, intriguing, thought-provoking, perspective-changing, paradigm-shifting…maze. This is a work of genius.” – J.J. Kilroy

“As you travel through the mansion, you suddenly notice funny things – the labyrinth seems to be turning in on itself. “Haven’t I been here before?” You are lost! Trapped! Muahahahaa!!!!”

“It all starts making sense at about 3 AM amidst frantically drawn loopy maps, fragments of rebuses and the fact that there’s just something *wrong* with the stick figure in the basement. That’s when you stare blearily at the page and say, “We’ve been blind, we’ve been blind the whole time,” and start babbling conspiracy theories.” – M. Glenn

“The most engrossing book ever.” – Lily D.

The Future…

Manson has agreed to make available a drawing from his incomplete sequel to MAZE and he appears at least somewhat open to a sequel. To quote, “There are many things I wish I could have put into MAZE that would have added even more depth. For this reason I have never let go of the idea of a sequel. Your site suggests to me there are people out there that would welcome a sequel. If there is interest, I may pick it up again.”

Let us hope he does! - White Raven 9-17-13

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.