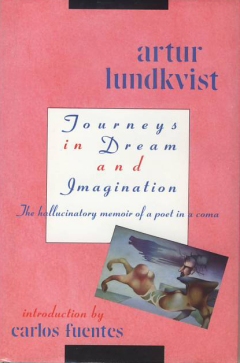

Artur Lundquist, Journeys in Dream and Imagination, Trans. by Ann B. Weissmann and Annika Planck, Four Walls, Eight Windows, 1991.

In 1981 the author, a well-known 75 year old Swedish poet, suffered a heart attack and lay comatose for two months. He then began a prolonged period during which he gradually recovered all of his faculties. In the early stage of his recovery, Lundkvist experienced a series of strange and intense "waking dreams," which he describes in this memoir. Many were dreams of journeys to real or fantastic places: for example, a trip to a railroad station in Chicago where physicians surgically transformed white people into black people, or a visit to a strange planet where cows produced blue milk. Lundkvist's memories of these dreams are embedded in a series of imaginative meditations on aging, human nature, the meaning of life, and the inexorable passage of time.

This short book is accurately subtitled "the hallucinatory memoir of a poet in a coma." The poet's meditations are unfailingly imaginative, gracefully written, and often very insightful. Lundkvist's clinical circumstance is not new: a patient hovering near the maw of death returns to life to report a profound experience that took place while others thought he or she was comatose or delirious. In this poet's version, the tale makes for astringent and elegant reading. It is interesting to compare these hallucinatory experiences with those reported by Richard Selzer in Raising the Dead (see this database), the book he wrote after experiencing a near-fatal episode of Legionella pneumonia.

I’m attracted to unusual states of consciousness in the history of literature, such as Hanna Weiner’s poetic conversations with the words that she saw projected, involuntarily, onto surfaces; and those “Kubla Khan’s” written during drug-induced altered states of consciousness. One of the most remarkable poetic records of an altered state of mind is Artur Lundkvist’s Journeys in Dream and Imagination: The hallucinatory memoir of a poet in a coma.

In 1981, at the age of 75, Swedish poet Artur Lundquist had a heart attack while giving a speech on Anthony Burgess. A friend administered artificial resuscitation and he was rushed to the hospital, where he lay in a coma in the intensive care unit for two months, his life sustained by a heart-lung machine. He gradually regained consciousness over the next few months, maintaining awareness for greater and greater periods of time. As soon as he was able to write again or at least to dictate to his wife, he attempted to re-capture the now-elusive dream visions that illuminated the two months of his coma as well as to set down the waking dreams that he experienced during the first year of his convalescence, intense and vivid ones in which his eyes remained open and during which reality mixed with unreality in a half-aware reverie. Such dreams are not uncommon for persons who have experienced a change in breathing patterns, as is the case being on a lung machine (1). Fortunately, Lundquist’s linguistic abilities were rusty but intact, and he was able to document his fantastical visions that arose during this fertile period of dreaming.

The memorable opening of his poetic journal of dreams, “I know I am traveling all the time,” suggests that he’s aware of his altered condition, and that the background noise of his mental state is his impression of traveling, paradoxically in “complete stillness and silence” and “without a sound or feeling of movement.” He exists “without distance in time and space” yet he feels that he is traveling “through time or space.” He can’t tell if he’s “lying in the same place” or “traveling without interruption.” He’s unaware of minutes and hours passing, “yet time is moving somehow.” It’s as though he existed in suspended animation while riding a train. He describes his state of mind during his convalescence as being full of contradictions: moving yet stationary, timeless yet in time, lonely yet also belonging, unaware yet on some level conscious. In this twilight state, while he’s on life support in the hospital, he dreams, sometimes about his own death and sometimes about the annihilation of the earth. Fantasies of nothingness, purposelessness, and oblivion haunt him in his awareness that his own consciousness could easily fritter away and end rather than be revived, and that eventually nothing will be left of the earth and all its life forms: “nothing that can see or feel or think remains in existence.”

His journey is metaphorical as well as viscerally sensed. The point of departure of the journey is a state of suspension in a world of silence and paralysis, as if he were in a cocoon. He seems to be neither conscious nor unconscious, and sometimes, for brief periods, he perceives the objects and people in his hospital room, but he’s helpless to make contact with them. The journey is one of transformation, and his destination is consciousness, the regained ability to speak and read, and ultimately, the ability to write about the journey of his dreams.

Yet he has no sense of destination in his dream journeys. What he has lost—his consciousness of place, of his body in a particular space, situatedness—becomes an obsession in his dreams. In a particularly poetic entry that is reminiscent of Stephen Dedalus’ meditation on place, telescoping from self to universe (2), Lundquist describes a village of farms in some detail, then zooms away:

behind that the forest began, and the moors, the meandering creek and the half-overgrown lake, the cows who grazed without fences, knew the paths and followed them, and returned when it was milking time,

then there was the church village and the whole parish, the district and the county and the whole country, and it was on earth in the universe, below the sun, the moon, and the stars, with years carved into tree trunks without revealing if the world was actually old or still young

Like Dedalus’ list, Lundquist’s image of an ever-expanding view tells of his wished-for certainty of place in an orderly world in which you know exactly where you are, even though there is a mystery about where you’re precisely bookmarked in the age of the world. When he does feel, in his dreams, a strong sense of self, that self feels alien to him: he doesn’t recognize the echo of his own shouting voice. It is absence and loss that most often shape his dreams, as when he envisions a couple buried alive after a strong earthquake, or a living, sentient stone mountain that is being cruelly and terrifyingly quarried by men who are more murderers than miners, or himself as the village idiot, “carry[ing] within [him] something that has never fully blossomed.” He’s in purgatory, a guest lost in a vast hotel, a village hidden in a mist. Corporeality and consciousness are absent or impaired, and desire—for life, for sexuality, for communication—is thwarted since the means necessary to fulfilling these desires are in a liminal state, halfway between action and immobility and unable even to know with certainty whether he is alive or dead.

Journeys in Dream and Imagination is a record of meta-dreams, meditations on Lundquist’s state of consciousness, dreams about the dream state. In the beginning of his journey, his dreams are “of iron, so strong, so durable.” However, this strong state of consciousness gradually starts “to rust,” and the dreams “fall off like flakes of rust” until they vanish entirely. He then switches “to dreams of dough,” which he bakes and eats, “almost like bread” that nourishes him through this period of amorphous half-consciousness. The metaphor of the consumption of dreams describes the interiority of his state of mind, and the next image of vomiting a snake that is also a giving birth to speech seems to signify his ability or desire to engage once more in communication with the world outside his twilight prison. Within his dream state, he sometimes interprets the vision he has just experienced, as when he sees trees growing between his toes and believes that dream to be a good omen, a “sign that life continues to grow inside me.” It is as though his consciousness were trying to solve the puzzle of its own impairment.

The necessarily interior turn during this period when perception of the outer world was subdued or shut off perhaps accounts for his awareness of his body, which he felt to be in a state of flux (the sensation of traveling, for example) and transformation: he has become something of a shapeshifter. In two successive dreams, he is transformed into a giant and then a miniature person, in the manner of Gulliver’s Travels. Proprioception is the brain’s ability to locate the position of the body relative to its own parts as well as to the exterior world. Since altered states of consciousness (during meditation or praying, for example) can change the strength of a person’s feeling of separation from or continuity with exterior space, other people, or objects, I wonder whether Lundquist’s dreams reflect disturbances in his proprioceptive sense of self in relation to others. During his convalescence, his brain was repairing itself—but was it also rehearsing, in a sense, the process of its own repair? Is this what the image of consuming the nourishing bread of his dreams signifies? If reinforcing the lessons of the day in a kind of rehearsal of knowledge is part of the function of dreams, as some neuroscientists studying sleep now believe, what was the purpose of Lundquist’s dreams, if indeed they can be said to have one? Why do so many of them have the feel of meta-dreams about the journey towards consciousness?

Regardless of the purpose of these dreams, it seems likely that Lundquist’s hallucinatory visions, alternately peaceful and nightmarish, represent his fears of being forever in a coma and his hopes of someday rejoining the realm of real people, objects, places. In his dreams, he creates worlds of uncertainty, where nothing can be pinned down as completely familiar and habitual; where communication is problematic or impossible, consciousness is present in some way but still suspended in a timeless, placeless journey; and where he is alien to himself and inhabits a world that is strange and unrecognizable.

His limbo is real and extreme, but there is something oddly familiar about his dilemma dramatized or described in his dreams, something that elicits the feeling that you’ve been there, too, in moments of doubt or frustration, when order dissolves, when thought fails to render its shiny nugget, when self seems irremediably scattered, when you feel alone on a teeming planet that seems to belong to another dimension, when talking to others falters and stumbles, when you no longer know who or why you are, and the world, faced ultimately with demise, seems pointless but stubbornly present. In his meta-dream stories investigating suspended being, the often surreal analogies for these states are almost endlessly inventive. But in them one can also read a description of what it is to be human, or to exist in “negative capability,” as Keats called the ability to live with “uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.”

Part of the pleasure of Lundquist’s record is becoming aware that even in a coma, the mind can cut seemingly endless facets in which to reflect itself and rehearse the dramas—miniscule or vast—of its journey through the interior. If his world seemed to be a solipsistic nightmare from which he couldn’t completely awaken, he peopled that world with rich possibilities and a self-awareness that sometimes comes across as more lucid and knowing—for all its twilight uncertainties—than the consciousness he so desperately wanted back.

(1) I gleaned most of the information in this narrative of Lundquist’s heart attack and recuperation from Carlos Fuentes’ introduction to the book.

(2) He turned to the flyleaf of the geography and read what he had written there: himself, his name and where he was. - Camille Martin

Outside of literary circles the name of the author is not well known in this country. Arthur Lundqvist (1906-1991) was a leading contemporary Swedish poet and author who, in addition to his prolific output (over eighty books of poetry and prose) was a prominent member of the Literary Committee of the Swedish Academy. As such he exerted considerable influence on the choice of Nobel laureates. Fluent in Spanish he was instrumental in bringing a new generation of Latin and South American writers to Sweden. (Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz). He is generally regarded as having brought modernism to the Swedish literary scene.

An inveterate traveler, urbane and cosmopolitan in outlook, he was truly a world citizen. He was also an autodidact. Brought up in a working class household his formal education terminated in the sixth grade. Early in his career he was identified with the generation of left-wing avant-garde writers. He has been described as proletarian in his sympathies and aristocratic in his writings. Like all Swedes he had a deep love for nature and never lost touch with his rustic roots.

In October of 1981 Artur Lundqvist suffered a severe heart attack, lost consciousness and lapsed into coma. He was kept alive on a heart-lung-machine but remained unresponsive for two months. His wife, Maria Wine, also a writer, remained at his bedside constantly and, despite the forebodings of his doctors, persisted in her efforts to reach him through poetry and song. The first indication that some measure of awareness had returned was a faint flicker of a smile in response to being told a funny story. It took many weeks for the recurrent stretches of clouded consciousness to dissipate and many months to regain most of the ground he had lost. In the years that followed he returned to writing and continued to be productive.

Published originally in Swedish this book came to my attention by Swedish colleagues who knew of my interest in dreams. As I made my way slowly through the Swedish edition I was amazed at the author's detailed recall of dreamlike imagery in connection with the prolonged coma and the slow recovery that followed. There is no clear timing of the events he describes but, from what I could gather, there were a few fragmented memories and impressions from the period of deep coma.

Most of his recall seems to be associated with his subsequent struggle to hold on to the fleeting moments of awareness. His inner life was particularly vivid during this period and was recounted later in elaborate detail. The result is a melange of dreams, dream-like imagery, flights of imagination and the exaggeration of various sensory impressions.

How does a gifted and richly imaginative person cope with the dreadful combination of enforced immobility and near total disconnect from the world he knew? Artur Lundqvist found a say which he describes in his opening words:

"I know I am traveling all the time, possibly with no interruptions, also with no tremors or noises, soundlessly and softly, and then I am no longer lying in my bed but stepping out into the world where everything is awake, sundrenched, comforting, and I am there clearly as a visitor, and I am quite at ease, it must be a dream journey I have undertaken, a definite dream journey where all is real, where all my wishes are fulfilled without my even asking, precisely the way all journeys ought to be, but maybe one has to be dead in order to journey like that."

Out of touch with his surroundings, entombed in a metal cabinet, he was able to create and later recall elaborately crafted metaphorical imagery that simultaneously reflected the confinement he was subjected to and the contrasting freedom he felt as his imagination took over. This "immobile traveller" as Carlos Fuentes refers to him in his Introduction, went on voyages to strange lands, witnessed strange happenings (cows giving purple milk, white people transformed into black people) and where strange things happened to him (varying in size from tiny to huge).

Not all was pleasantly wishfulfilling. Although he usually experienced himself as a detached observer, the scenes he witnessed on his journeys reflected poignantly his touch and go encounters with the ever-present threat of total oblivion. Scenes of passion, sensuality and beauty are offset by images of death, barrenness and petrifaction. He comes upon starving people who wear their skeletons outside their bodies. He muses about the sun as a "master of space ... tearing itself apart ... bearer of unbearable forces constantly destroying themselves". He reflects on the evanescence of life as he watches a rain drop splash against a window or a snowflake falling and disappearing.

His feelings of confinement are metaphorically transformed:

"I wake up and find myself in surroundings with no vertical dimensions, the room seems to close just above me, leaving no space at all to sit up, I am forced to lie there straight on my back unable to turn on my side. He experiences a suffocating anxiety: ... now the horrifying thought comes to me that maybe I am in a coffin without having the slightest idea how I ended up there, possibly already considered dead. On another occasion he finds himself in a cage as if in a zoo with a crowd staring at him with curiosity. He comes across a building designed and built along time ago by two Japanese architects and wonders if they had been walled into the building alive.

The sense of his own cognitive loss is depicted in the inept and helpless feelings as a hotel guest in a land where he is ignorant of the language. He has difficulty negotiating even the simples amenity: "How badly suited you are to being a hotel guest, from the very beginning you feel suspect, you use the wrong expressions even in your own language, not to mention others ..." Dealing with the reception desk is "purgatory". He does not know where to leave the key or whether or not to say good morning.

Soon after the return of consciousness, when he discovered he could no longer write, he describes an anosognosia-like response. He blames his hand for the problem and suggests "... perhaps I could replace the hand one way or the other, perhaps have a new hand from a dead person surgically attached".

He captures the essence of dreaming itself when he notes: " ... how easy to lift the past to the surface and perceive its strange reality as present, but ... it escapes (as) from the hand cupped around water", or: "My dreams are of iron so strong, so durable, but they soon begin to rust and nothing is left of them".

This edition includes a Preface by a neurophysiologist, dr David Ingvar, who had an extended interview with Lundqvist during his period of recovery, an Introduction by Carlos Fuentes and a Foreword by Maria Wine; his wife of over fifty years. Dr Ingvar recounts the onset of the illness and some of the details of his stay in the intensive care unit. During the course of their conversation the subject of death came up. Lundqvist's response was: "But I know what happens now. It finishes. The world disappears. It is quite simple".

In her foreword Maria Wine writes movingly of her long vigil trying to keep hope alive despite the gloomy prognostications of the medical staff. To what extent did her persistent daily efforts to reach her husband through the poems and music he loved play a role in his recovery? A question not to be dismissed lightly! She writes: "Suddenly you were gone, and yet not quite gone: you lay there with large, open, astonished eyes, as if something invisible had interrupted their last visual impression, your pupils seemed wordless like black lackluster stones, yet in the greyish-blue iris of your eyes there was a hint of a milky white shimmer ... your face was dreamlike and still, you were like a 'dreamer with open eyes'". The latter was a reference to a book Lundqvist wrote in 1966, perhaps with some prescience, entitled "Self Portrait of a Dreamer with open Eyes".

Fuentes notes the metaphorical power of Lundqvist's imagery in translating, as the poet does, living experience into art, even the living experience of being so close to a sustained death-like state. In a wide-ranging explication of Lundqvist's account he sees connections to Aztec mythology, to man's effort to identify with and remain separate from nature, and finally as an epiphany of the changing state of European consciousness.

As is the case with any successful literary effort, this book stands on its own, apart from context. In this instance, however, knowing the context adds a significant psychological dimension, revealing as it does, the congruence between the imagery evoked and the nature of the life threatening circumstances under which it was generated. I would have liked to have been privy to greater clarity about the course of the illness and the timing of the various images that were recalled. That might satisfy my scientific curiosity but at the cost of greedily pursuing my own interest in the face of a perfectly satisfying aesthetic experience. The imaginative realm was Lundqvist's last remaining resource. He certainly put it to good use, enabling us to share with him what he described as "an autobiography visualized in a state of unconsciousness". For more of that autobiography to become available to an American audience I would hope that some day the hundred and two vignettes omitted in this edition will be made available in English.

In closing, I want to pay tribute to the superb translation by Ann B. Weissman and Annika Planck. They captured in full the lyrical quality of Lundqvist's prose. - Montague Ullman

I CONFESS that opening this fascinating, lyrical, out-of-body travel book to the table of contents was a little daunting. First, a medical history by David Ingvar, the chief of the department of clinical neurophysiology at the University of Lund in Sweden; next, a preface by the author's wife, Maria Wine, a writer; then, an encomium by Carlos Fuentes. All this just to prepare the reader for a slender volume of what appear to be prose poems, smoothly translated from the Swedish by Ann B. Weissmann and Annika Planck.

But

the story behind "Journeys in Dream and Imagination,"

written by Artur Lundkvist, who died last month at the age of 85, is

almost incredible. After suffering a massive heart attack while

delivering a lecture on Anthony Burgess in 1981, Lundkvist, a Swedish

poet, linguist, essayist and influential member of the Nobel Prize

committee who brought many Latin American authors to the world's

attention, lay in a coma for two months. His doctors thought his

chances for recovery were very slim, and that if he did revive, he

would probably spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

Despite

the doctors' disparagements, though, Lundkvist's wife came to the

hospital twice a day to sing to his inert form, read poems and

recount their shared experiences while he lay there, eyes open but

unseeing, lungs breathing with the help of a respirator. After six

weeks, amazingly, he began to rouse for brief periods. When his

breathing tube was removed, he was instantly able to speak. His

knowledge of five languages returned to him intact. And as he

recovered from his ordeal, he began to record the strange and vivid

journeys that he had taken during his long coma.

Many

people who have experienced a similar return from clinical death

report that they traveled down a long tunnel toward a blinding source

of light. And for some, this trip has served as a comforting

indication that there is life after death. But Lundkvist, who was an

unrepentant secularist, shows us quite another view:

"I

have met imperceptible death, without recognizing it, as an ever so

rapidly passing pain, not a moment of suffocation or anxiety, / now I

know that death is nothing once it has arrived . . . a repose like an

extinguished flame, leaving no trace, / there is no meaning to your

having lived . . . / but we are bound to the concept that nothing has

a meaning unless it is transformed into something else, a consequence

of our incorrigible overestimation of ourselves."

Aware

of his blasphemy, he then assumes the voice of his accusers: "you

have been unconscious for two months, and if you haven't seen God in

that time you are beyond hope."

Lundkvist

came back from the edge of the abyss, from his paradoxical immobile

voyage of discovery, with reports of excursions so richly

adventurous, so full of vivid and concrete detail, so packed with the

furniture and geography of his hallucinatory travel as to charm the

casual reader, deeply engage the poet and captivate the harshest

skeptic. Once, as he watches two green saplings emerge from between

his toes, he wonders, "will I have to water them and tend them .

. . will I still have to put on some kind of shoes to protect the

plants without preventing their growth." Another time he flies

with the wind. Often he drifts over water. Occasionally he is

conveyed by train. In one hallucination he is a sort of Gulliver, in

the next a Lilliputian; in each, he is filled with erotic desires,

which are inventively consummated.

Several

of his dreams allow him to return to the landscape of his boyhood,

filled with blacksmiths and women working spinning wheels, quarry

diggers and nuns. Others find him in Germany, Italy, China. A dog

recurs, "a shadow dog I cannot clearly perceive . . . / it might

be an unfortunate soul imprisoned in its fur . . . hoping each time

that I am the human it is looking for, the one who will recognize it

and give it a right to exist." There are birds "painted in

a cubist fashion, with sharp angles and curves, brilliantly colored

with red against blue and yellow against green, as if they were

camouflaged for living in the jungle." And there are seals "no

bigger than half-grown cubs, they have a finely textured light-gray

skin, as soft as fine gloves, their eyes are clear blue and twinkling

with joy."

Such

commonplaces as clouds, sun, cold, the nature of greenness, the

distant kinship between human form and the elements of the universe

-- subjects before which most poets quail, fearful of uttering

banalities -- evoke from Lundkvist an extraordinary metaphorical

response. At times his lyrical voice is overridden by realism,

especially when he takes on global issues like hunger, pollution,

desertification and man's propensity to wage war. But virtually every

entry in this little book turns up buried treasure.

Lundkvist

has made imaginative leaps that are truly breathtaking and

startlingly apt. But more than anything, "Journeys in Dream and

Imagination" is a tribute to human courage. As Carlos Fuentes

suggests in his introduction, Lundkvist "has never been beaten,

he has simply been, all this time, at the center of an unfathomable

mystery . . . at the epiphany where our awareness of humanity is our

innermost self." - Maxine

Kumin

excerpts:

I know I am traveling all the time, possibly with no interruptions, also with no tremors or noises, soundlessly and softly, and then I am no longer lying in my bed but stepping out into the world where everything is awake, sundrenched, comforting, and I am there clearly as a visitor, and I am quite at ease,

it must be a dream journey I have undertaken, a definite dream journey where all is real precisely the way all journeys ought to be, but maybe one has to be dead in order to journey like that,

by the way, how can I know I am not dead, even though I have no sensation of being dead, and it is as if I rest in a middle zone without feeling either warmth or cold or hunger or any human needs

* * *

No wind, not even the slightest breeze, complete stillness and silence, yet I am traveling or have a definite sense of traveling, but how can it happen without a sound or feeling of movement,

can I travel motionless or glide onwards without the least resistance from the earth or the air, can it be that time has stopped or speed no longer has a meaning, that I have reached the crossroads beyond motion and stillness . . .

but yet I am here, can feel my body and sense my breathing, it is a nothingness that is definite, but without any wind or air or sound whatsoever, as if all but my own being has ceased existing,

it amazes me somewhat, but it actually does not matter, why should I need wind and sound, that which exists does exist nevertheless, and I must be the one perceiving it, and that is surely sufficient to make me alive and capable of perceiving,

I do not know what time has passed, but now I begin hearing something, at first vaguely, then with increasing strength, and soon, I can recognize a distant song by women, a choir like in a church but heard from a distance, the song rises and falls rhythmically, with different voices blending, lighter ones and darker ones,

It is actually not beautiful, but it still makes an impression by its inherent certainty and power, yes, the song bears witness of a conviction that conquers silence and nothingness as if journeying by its own force and conquering all resistance,

I feel that I am again traveling, that immobility and silence no longer reign, but I don not know what the women are singing or what the song means, it is simply there, filling the room which was only silence and emptiness

* * *

The silence is like a fine spiderweb against my face, I cannot rub it off, it is simply there without being tangibly real, it does not flutter like a leaf in the breeze, nor is it entirely immobile, it feels like the impression of a wind that is already becalmed, it is hardly the beginning of the weave and it does not betray a pattern, it is the most insignificant matter, yet it makes itself known

* * *

My dreams are of iron, so strong, so durable, but they soon begin to rust, eventually they fall off like flakes of rust and nothing is left of them, then I shift to dreams of dough so that I might bake and eat them, almost like bread,

suddenly, as I sit at the table in good company, I am nauseated, I do not even have time to stand up and run to the toilet before I spew out a snake that curls out of my mouth, one piece with each spasm, like a birth,

the snake lands in front of me, on the plate that is still empty, it is curled up, mottled, with a zigzag pattern on its back, more beautiful than a sausage and much longer,

the snake raises its head and opens its jaws as if to say something but at that moment, I faint and I do not hear it. - rogueembryo.com/2009/09/12/i-know-i-am-traveling-all-the-time-the-twilight-dreams-of-artur-lundquist/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.