Patrick Lawler, Rescuers Of Skydivers Search Among The Clouds, Fiction Collective 2, 2012.

excerpt

read it at Google Books

Winner of the 2013 CNY Book Award for Fiction.

When you step inside Patrick Lawler’s Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, you will find yourself hovering in the clouds, among a family and a town, and in the world of one of fiction’s most inventive writers.

When you step inside Patrick Lawler’s Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, you will find yourself hovering in the clouds, among a family and a town, and in the world of one of fiction’s most inventive writers.

Patrick Lawler’s novel is about resonance, echoes, and naming; about hiding inside of names; about standing completely still; and about the fractalization of family. Connect the dots. Connect the secrets. Mother. Father. Sisters. Brother. Every character wears a variety of masks, and every place is also someplace else.

Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds is a reconfiguring of narrative―how stories exist inside stories, how place exists inside self, how self exists inside others, and how parachutists exist inside clouds.

Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds has the one-two punch of an evocative title and a beautiful cover of a rowboat pulling people from a hot air balloon's water landing. It's a cover sure to draw the eye of anyone, like me, intrigued by the out-of-the-ordinary and the not-quite-predictable, though these days both of those seem to have become marketing categories rather than descriptions. Nonetheless, the cover is worth a few sentences of admiration.

The novel inside is composed of brief sections that range in length from a sentence to a few pages, each one titled in bold and containing the narrator's memories of an undisclosed time from childhood. The memories are composed of brief summaries of events, snippets of dialogue, and lists of book titles and the wording on signs. The place is never specified but has the familiarity of a suburb or small town, where the mayor and the neighbors are as important as the mother, father, and siblings who reappear in every section. That familiarity, though, is leavened by absurd and fantastical events that are balanced between the literal and metaphorical. On the first page, the mayor is dissatisfied with the street names, so they change between the names of assassinated presidents, types of berries, and emotions. A few paragraphs later, the narrator says, "It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the sky or lived in the earth." The connection between this and the street names or the description of the father's employment as a beekeeper follows a kind of dream logic -- it resonates without being fully explained.

"That was the year when," the narrator says, pinning time down with events, though as the phrase is repeated over and over, time slips free of its context. Yet the sections are not entirely atemporal. Story arcs are formed, though primarily from the changing relationships between the narrator and various characters rather than through events. For example, the narrator's love interest tells him "Whatever" when he first confesses his love to her and is referred to throughout by modifications of "whatever" that seem to indicate changes in how she treats him: "Meanwhile Girl," "Therefore Girl," "Since Girl," and so on. Other characters appear and disappear and appear again at various places in the text, including the narrator's brother, grandmother, and father. Though loosely tied to specific events, these disappearances are firmly rooted in emotion. "After my grandfather died, my grandmother became a window," the narrator says, evoking loss, death, and love all together.

The feeling of atemporality comes in part from these memories dancing across time rather than settling into it. Memories are presented in summary -- "That was the year we dreamed in lists" -- as often as they are presented as events -- "In school we studied how to change the world, but I didn't do that well on the exam" -- and even the events exist for no more than a sentence or a paragraph. They blow away in a puff of laughter or sadness, only to return pages later.

Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds is about nostalgia, but it also plays with a sense that the calm appearance of the past -- the nuclear family, the suburb or small town, the carefree childhood -- masks chaos. The novel begins with an epigraph from Ursula K. Le Guin's "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas." Le Guin's short story describes Omelas as a fantastically happy place, not without nuance and subtlety, but nevertheless happy in way we can't quite understand. Their processions and festivals are described, as are the people, including the line that appears at the beginning of Rescuers of Skydivers: "A child of nine or ten sits at the edge of the crowd, alone, playing on a wooden flute." This line is part of the impossible happiness of the place, but immediately after comes the foundation of Omelas's happiness: a child, kept wretched and alone in the basement of one of the buildings. The child in the basement and the child playing the flute are set up as necessary opposites of each other. The happiness of the flute-playing child is dependent on the misery of the child in the basement.

The narrator, too, plays a flute and is surrounded by both control and chaos. Apocalypse hovers around the corner, but so does the sense that "Something joyful sat above us." Images and experiences fracture and then repeat, exhausting the reader with repetition at first and then building momentum. Lines contain double meanings, moving easily between jokes and regret. And the skydivers might never come down. - Sessily Watt

http://www.bookslut.com/fiction/2013_01_019767.php

Readers of Patrick Lawler’s first novel, Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, can look forward to a treat—but only if they can divest themselves of the current (and, to my mind, lamentable) divide between poetry and fiction. This is certainly not the first attempt by an author to bridge this gap—one fine example of a writer working in this vein can be found in Anne Germanacos’s In the Time of the Girls, (reviewed in Blackbird v10n2)—fiction which uses a loose verse format and poetic structure to create startlingly arresting story images. In spite of examples such as this, however, readership and authorship for poetry versus fiction have certainly become more divided during the twentieth century, and do not seem to be moving closer in the twenty-first; therefore Lawler’s masterful way of simply ignoring the constraints of either, while incorporating the best of both, is all the more welcome. Lawler takes the blending of poetry and fiction to a new level in his work, an achievement for which he has won Fiction Collective Two’s Ronald Sukenick/American Book Review Innovative Fiction Prize.

Those who have a traditional notion of the novel may at first find the structure confusing. Lawler titles his chapters with sentences that could serve (and sometimes do) as the beginning of the actual text (the first is entitled, “My Mother Walked Down Joy Boulevard. My Father Was A Beekeeper.”), which itself defies linear structure by going to and from particular themes, mixing references to people and places, so that the reader gets an almost collage-like impression of the sentences and even words, as if the author wrote a very loose description of people and events, and then cut them up and rearranged them to create new and sometimes startlingly lovely combinations. The narrator opens the book with a seeming-explanation of the name of the chapter, which also works as an introduction to the place:

In the second paragraph of the first chapter, we’re introduced to the narrator’s family:

This opening also contains the beginning of one of Lawler’s favorite tricks—to open sentences with the same phrase repeatedly, always adding a new phrase to complete it, so that “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the sky or lived in the earth” after the description of the bees, becomes “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the story or lived in the words,” after “One day I wrote a poem and my mother sprinkled holy water over everything”; and then, “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the filled or lived in the empty” following “Years later my father became a bee sipping from an aluminum flower. . . . I called the family together for the Magic show. I didn’t have a veil big enough.” This new convention of Lawler’s gives the impression of a child’s-eye view, a narrator young enough to want to explain the workings of his family and life, but not old enough to understand that he can’t make a new rule every time he opens his mouth. The reader comes away with a new kind of understanding—of course you can make a new rule about families every time you discuss them; their true nature, Lawler seems to be saying, shifts sneakily every time you look.

The mood of the chapters progresses from the uncomplicated happiness of a young family (“My mother always felt something really good would happen. . . . Mostly we ate honey”) to something more complex (“Part of the problem was we couldn’t distinguish between a dream and an egg. That was the year we kept losing things”), as Lawler develops a new convention—the repetition of particular iconic symbols, paired with various ways to interpret them:

The images to which Lawler chooses to return seem to be chosen by a child, trying to make sense of his immediate surroundings—birds, the sky, the neighbors, what he learns in school, the various (and telling) occupations of the father, the moods and preoccupations of the mother, what the TV said, what he ate, the relationship between the house and the cellar; but Lawler takes these commonplace observations and makes them both remarkable and somehow truthful:

These images and many more reoccur throughout the short, fragmented chapters, and the various combinations they form indicate the growth, struggles, and tragedies, small and large, that the novel’s family undergoes. Gradually, plot emerges, and the themes begin to grow up along with the narrator: “The Since girl talked to me after class. Gravity had already memorized her body, and I ran out of things to say. I could feel a hook inside my heart.” And, “That was the year I listened to my parents having sex. . . . Sadness followed my father home. That was the year I saw a woman lying on a grave—crying. . . . That was the year I kept hearing my mother say no.” And, in a chapter called “At School I Write a Story Called ‘Genitalia,’” “That year the boys in school tried to look up the skirt of the However Girl.”

Lawler does well to contrast these relatively lighthearted images about sex with the darker, more adult side of the same theme:

When we read traditional fiction, we can easily see the difficulty in ordering details of plot, development of character, the continuation and deepening of themes, and making it all interesting. In Lawler’s novel, his ability to make the arrangement of the sentences appear to be happenstance, while at the same time coaxing poetic meaning out of their order, makes Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds particularly distinctive. His technique of skillful experimentation with the ways apparently unrelated phrases and ideas can be connected yields a new and oddly truthful meaning for each; the reader feels the emotions of the characters and understands how they suffer, and why it’s important.

Patrick Lawler has published of three collections of poetry: Feeding the Fear of the Earth; A Drowning Man is Never Tall Enough; and (reading a burning book). All three have been praised as groundbreaking for the fearlessness of the subject matter and the unlikely gatherings of characters. In Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, Lawler has taken his unbounded sense of what can be done with words and ideas a step farther; in creatively and successfully combining the conventions of both poetry and fiction in one book, and having the temerity to call it a novel, Lawler accomplishes another step towards what should be happening throughout the literary world—the undoing of genres. - MICHAUX DEMPSTER

https://blackbird.vcu.edu/v12n1/nonfiction/dempster_m/search_page.shtml

Not long ago I saw a photo collection: Two brothers who took one picture every year in the same month, the same pose. They did this for decades, their entire lives distilled in these portraits. In 1994 they wear matching sweaters. In 2001 they look unkempt. Each photograph asks the onlooker to imagine what happened between each set of images–why did he lose weight, why wasn’t he smiling more. The positioning grows expected, even stale: older brother here, younger brother here, chair, table, lamp. Except, as we grow closer to the now, we see the paint has started to chip on the wall, and the lampshade was replaced, and somewhere, somehow, two young boys grew into men.

The framework remains unchanged, the details shift in the smallest of ways. But the overall effect creates nostalgia for suggested things, unseen things, palpable just beneath the surface.

It’s a difficult thing to accomplish, and it’s what Patrick Lawler’s first novel, Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, spends its pages exploring: The spaces between and underneath. The economy of storytelling. The onus on the viewer to participate in unpacking questions, and meanings, and movements.

Composed in a series of tightly wrought chapters–some a mere three sentences long–the story follows a young narrator and his family, in a small, anonymous town, with small, anonymous descriptors. They seem to both live in and hover over the landscape. The important things are named and renamed, redefined as they change–or as the narrator’s perspective on them changes. Those named things become the notable landmarks of the novel, their evolution or transformation or renaming emblematic of the narrator’s own journey and perspective on those around him.

Lawler says it explicitly: “Our stories repeat themselves endlessly around us–ultimately revising who we are every time.”

It feels at once like reading the same chapter over and over again with certain words replaced, but this heightens the effect of those changed words and phrases. The same photograph, with things just a little older, a little changed. We begin in “the year they named the streets after the elements,” moves into “the year my parents began speaking in a strange language” and “the year we practiced for emergencies.” By the end, the repeated frameworks have become as nostalgic as old photos — in them, we see the history of all the shifts the narrator and the reader have together experienced. And in the rare deviations, we see the narrator looking beyond, departing: “‘This is where we are,’ he said, but his mouth was filled with uncertainty.”

The reader is forced to consider her own story in patterns and revisions, in names and malleable perspectives. I consider my own: The year that smelled of pool water and talcum powder. The year our neighbor’s daughter asked Santa for a penis. The year I drove in circles hoping to get lost, and failing. How best to crystallize time and experience in ways that approximate truth.

Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds is a poet’s fiction, but it’s an artist’s fiction too—because the brevity and economy of language makes the act of reading this novel something beyond reading, because the entire work seems to meditate on how we live in words, how we cohabitate with them in our daily routines and use them as mile-markers for landscapes past. How eventually, we become symbols of the lives we live, and how the uncertainty of detail grants us room to explore. - Jennifer Dane Clements

https://asitoughttobe.com/2013/12/23/a-review-of-patrick-lawlers-rescuers-of-skydivers-search-among-the-clouds/

The novel inside is composed of brief sections that range in length from a sentence to a few pages, each one titled in bold and containing the narrator's memories of an undisclosed time from childhood. The memories are composed of brief summaries of events, snippets of dialogue, and lists of book titles and the wording on signs. The place is never specified but has the familiarity of a suburb or small town, where the mayor and the neighbors are as important as the mother, father, and siblings who reappear in every section. That familiarity, though, is leavened by absurd and fantastical events that are balanced between the literal and metaphorical. On the first page, the mayor is dissatisfied with the street names, so they change between the names of assassinated presidents, types of berries, and emotions. A few paragraphs later, the narrator says, "It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the sky or lived in the earth." The connection between this and the street names or the description of the father's employment as a beekeeper follows a kind of dream logic -- it resonates without being fully explained.

"That was the year when," the narrator says, pinning time down with events, though as the phrase is repeated over and over, time slips free of its context. Yet the sections are not entirely atemporal. Story arcs are formed, though primarily from the changing relationships between the narrator and various characters rather than through events. For example, the narrator's love interest tells him "Whatever" when he first confesses his love to her and is referred to throughout by modifications of "whatever" that seem to indicate changes in how she treats him: "Meanwhile Girl," "Therefore Girl," "Since Girl," and so on. Other characters appear and disappear and appear again at various places in the text, including the narrator's brother, grandmother, and father. Though loosely tied to specific events, these disappearances are firmly rooted in emotion. "After my grandfather died, my grandmother became a window," the narrator says, evoking loss, death, and love all together.

The feeling of atemporality comes in part from these memories dancing across time rather than settling into it. Memories are presented in summary -- "That was the year we dreamed in lists" -- as often as they are presented as events -- "In school we studied how to change the world, but I didn't do that well on the exam" -- and even the events exist for no more than a sentence or a paragraph. They blow away in a puff of laughter or sadness, only to return pages later.

Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds is about nostalgia, but it also plays with a sense that the calm appearance of the past -- the nuclear family, the suburb or small town, the carefree childhood -- masks chaos. The novel begins with an epigraph from Ursula K. Le Guin's "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas." Le Guin's short story describes Omelas as a fantastically happy place, not without nuance and subtlety, but nevertheless happy in way we can't quite understand. Their processions and festivals are described, as are the people, including the line that appears at the beginning of Rescuers of Skydivers: "A child of nine or ten sits at the edge of the crowd, alone, playing on a wooden flute." This line is part of the impossible happiness of the place, but immediately after comes the foundation of Omelas's happiness: a child, kept wretched and alone in the basement of one of the buildings. The child in the basement and the child playing the flute are set up as necessary opposites of each other. The happiness of the flute-playing child is dependent on the misery of the child in the basement.

The narrator, too, plays a flute and is surrounded by both control and chaos. Apocalypse hovers around the corner, but so does the sense that "Something joyful sat above us." Images and experiences fracture and then repeat, exhausting the reader with repetition at first and then building momentum. Lines contain double meanings, moving easily between jokes and regret. And the skydivers might never come down. - Sessily Watt

http://www.bookslut.com/fiction/2013_01_019767.php

Readers of Patrick Lawler’s first novel, Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, can look forward to a treat—but only if they can divest themselves of the current (and, to my mind, lamentable) divide between poetry and fiction. This is certainly not the first attempt by an author to bridge this gap—one fine example of a writer working in this vein can be found in Anne Germanacos’s In the Time of the Girls, (reviewed in Blackbird v10n2)—fiction which uses a loose verse format and poetic structure to create startlingly arresting story images. In spite of examples such as this, however, readership and authorship for poetry versus fiction have certainly become more divided during the twentieth century, and do not seem to be moving closer in the twenty-first; therefore Lawler’s masterful way of simply ignoring the constraints of either, while incorporating the best of both, is all the more welcome. Lawler takes the blending of poetry and fiction to a new level in his work, an achievement for which he has won Fiction Collective Two’s Ronald Sukenick/American Book Review Innovative Fiction Prize.

Those who have a traditional notion of the novel may at first find the structure confusing. Lawler titles his chapters with sentences that could serve (and sometimes do) as the beginning of the actual text (the first is entitled, “My Mother Walked Down Joy Boulevard. My Father Was A Beekeeper.”), which itself defies linear structure by going to and from particular themes, mixing references to people and places, so that the reader gets an almost collage-like impression of the sentences and even words, as if the author wrote a very loose description of people and events, and then cut them up and rearranged them to create new and sometimes startlingly lovely combinations. The narrator opens the book with a seeming-explanation of the name of the chapter, which also works as an introduction to the place:

That year the mayor decided to name the streets after presidents who had been assassinated. He was never satisfied. According to him a town’s character was written across it in the names of its roads. Once the streets were named after berries, so we walked down Choke Cherry Lane or Elderberry Road or Raspberry Way. These names gave us places to live our lives. Girls could be lusted after on Strawberry Street. Boys could smoke cigarettes, watching clouds of hair from the corners of dark red/blue intersections. The mailman would lug his bloated bag down Boysenberry. . . . The mayor made a conscious effort to select the edible berries though some poisoned ones slipped in—which led him to go with the assassinated president idea.This opening, though it appears arbitrary and fanciful, actually does a thorough job of depicting the kind of place we’re to inhabit throughout the book—a small town where families and civil servants live their typical lives, made extraordinary through Lawler’s fantastical invention.

In the second paragraph of the first chapter, we’re introduced to the narrator’s family:

When I was born they named the streets after emotions: my mother walked down Joy Boulevard. My father was a beekeeper. Almost robotic among the bees with his smokepot and his bee clothes, almost feminine with his netted face. I spent my childhood with bee stings. My mother was a hagiologist studying saints. My sisters would spend afternoons digging for relics in the backyard. The bees were ambassadors from an ordered and enchanted world. They were scholars obsessed with an ideal, always returning to the same roundish, yellow perfection of their lives. Flying alchemists. . . . It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the sky or lived in the earth.In these opening paragraphs, possibly the most linear of the entire book, Lawler mostly connects ideas one after the other, rather than scrambled and reordered; yet because of the images that he has chosen, we get a strong sense of the wonder of childhood, and the magic that surrounds young families in their everyday settings.

This opening also contains the beginning of one of Lawler’s favorite tricks—to open sentences with the same phrase repeatedly, always adding a new phrase to complete it, so that “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the sky or lived in the earth” after the description of the bees, becomes “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the story or lived in the words,” after “One day I wrote a poem and my mother sprinkled holy water over everything”; and then, “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the filled or lived in the empty” following “Years later my father became a bee sipping from an aluminum flower. . . . I called the family together for the Magic show. I didn’t have a veil big enough.” This new convention of Lawler’s gives the impression of a child’s-eye view, a narrator young enough to want to explain the workings of his family and life, but not old enough to understand that he can’t make a new rule every time he opens his mouth. The reader comes away with a new kind of understanding—of course you can make a new rule about families every time you discuss them; their true nature, Lawler seems to be saying, shifts sneakily every time you look.

The mood of the chapters progresses from the uncomplicated happiness of a young family (“My mother always felt something really good would happen. . . . Mostly we ate honey”) to something more complex (“Part of the problem was we couldn’t distinguish between a dream and an egg. That was the year we kept losing things”), as Lawler develops a new convention—the repetition of particular iconic symbols, paired with various ways to interpret them:

“Words hurt,” said my Grandmother.Here Lawler’s repeated interpretations use the literal child’s-view perspective to explore the way books and words affect us—in the world that Lawler creates, they have the power to cause physical damage. In contrast to the seriousness of the literal situation here, Lawler also uses this youngster’s point of view for sly humor quite often—we know that there is a double meaning, which often creates a delightful inside joke between author and reader.

“Words hate us,” said my brother.

Standing in front of my Grandmother’s bookcase, I felt the vibrations and hunger. Each book nudged its way into the next book—one book being eaten by another.

“Words collect in the corner of the mouth,” said my older sister.

That was the year there was an accident in the library, and we were thankful we lived next to a mirror factory. . . . A man who was in the library accident was buried under classics. When they tried to rescue him they started drilling down through the books and lowering mirrors to see if there was any breathing. . . . In the library they tried to yank the man out from under the words, but it was futile.

The images to which Lawler chooses to return seem to be chosen by a child, trying to make sense of his immediate surroundings—birds, the sky, the neighbors, what he learns in school, the various (and telling) occupations of the father, the moods and preoccupations of the mother, what the TV said, what he ate, the relationship between the house and the cellar; but Lawler takes these commonplace observations and makes them both remarkable and somehow truthful:

For school we had to make a list of things we were afraid of. My list included:When Lawler strings together these seemingly arbitrary associations—learning about fear in school, conflicting messages from the media, neighbors’ strange goings-on, and the fear of the cellar—in his looks-random-but-really-very-purposeful way, he forms a new atmosphere, a tone that we somehow recognize from our own childhood, and maybe adulthood, too.

ELECTRICITY

FACTS

BREATHING TUBES

GETTING CAUGHT . . .

The TV said: Look at the pretty. The TV said: There are no consequences.

The TV said: Worry. . . . That was the year our neighbors gave their children away. Garage sales everywhere were filled with doll clothes and broken appliances and stone clocks with garnet gears. . . . If you looked deeply into the cellar you could see a crater where the heart of the world had been taken . . . In school I learned there would be transition stories—stories between the old stories and the new stories. . . . I had forgotten how to read.

These images and many more reoccur throughout the short, fragmented chapters, and the various combinations they form indicate the growth, struggles, and tragedies, small and large, that the novel’s family undergoes. Gradually, plot emerges, and the themes begin to grow up along with the narrator: “The Since girl talked to me after class. Gravity had already memorized her body, and I ran out of things to say. I could feel a hook inside my heart.” And, “That was the year I listened to my parents having sex. . . . Sadness followed my father home. That was the year I saw a woman lying on a grave—crying. . . . That was the year I kept hearing my mother say no.” And, in a chapter called “At School I Write a Story Called ‘Genitalia,’” “That year the boys in school tried to look up the skirt of the However Girl.”

Lawler does well to contrast these relatively lighthearted images about sex with the darker, more adult side of the same theme:

After our father left, my mother kept putting up warnings around the house.Lawler’s seemingly artless way of arranging the less and more sinister problems associated with sex side by side with each other not only sets up another, and darker, inside joke for the reader to understand and appreciate, but also allows the reader to see how sex, as well as other difficult family issues, can be both delightful and terrible, and to feel the power of each iteration.

If you ever get thrown in the trunk of a car, kick out the back tail lights and stick your arm out the hole and start waving.

After my father left, I heard one of my aunts say to my mother, “That’s just the way men are. If he’s not thinking about yours, then he’s thinking about somebody else’s.”

That was the year the household went through considerable amounts of Kleenex. . . .

My uncle said,

“I’ll tell you how to treat a woman.”

“What about our aunt?” my brother and I asked.

“She’s a wife,” he said.

“I think it has something to do with flowers,” said the Latin teacher.

When we read traditional fiction, we can easily see the difficulty in ordering details of plot, development of character, the continuation and deepening of themes, and making it all interesting. In Lawler’s novel, his ability to make the arrangement of the sentences appear to be happenstance, while at the same time coaxing poetic meaning out of their order, makes Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds particularly distinctive. His technique of skillful experimentation with the ways apparently unrelated phrases and ideas can be connected yields a new and oddly truthful meaning for each; the reader feels the emotions of the characters and understands how they suffer, and why it’s important.

Patrick Lawler has published of three collections of poetry: Feeding the Fear of the Earth; A Drowning Man is Never Tall Enough; and (reading a burning book). All three have been praised as groundbreaking for the fearlessness of the subject matter and the unlikely gatherings of characters. In Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, Lawler has taken his unbounded sense of what can be done with words and ideas a step farther; in creatively and successfully combining the conventions of both poetry and fiction in one book, and having the temerity to call it a novel, Lawler accomplishes another step towards what should be happening throughout the literary world—the undoing of genres. - MICHAUX DEMPSTER

https://blackbird.vcu.edu/v12n1/nonfiction/dempster_m/search_page.shtml

Not long ago I saw a photo collection: Two brothers who took one picture every year in the same month, the same pose. They did this for decades, their entire lives distilled in these portraits. In 1994 they wear matching sweaters. In 2001 they look unkempt. Each photograph asks the onlooker to imagine what happened between each set of images–why did he lose weight, why wasn’t he smiling more. The positioning grows expected, even stale: older brother here, younger brother here, chair, table, lamp. Except, as we grow closer to the now, we see the paint has started to chip on the wall, and the lampshade was replaced, and somewhere, somehow, two young boys grew into men.

The framework remains unchanged, the details shift in the smallest of ways. But the overall effect creates nostalgia for suggested things, unseen things, palpable just beneath the surface.

It’s a difficult thing to accomplish, and it’s what Patrick Lawler’s first novel, Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, spends its pages exploring: The spaces between and underneath. The economy of storytelling. The onus on the viewer to participate in unpacking questions, and meanings, and movements.

Composed in a series of tightly wrought chapters–some a mere three sentences long–the story follows a young narrator and his family, in a small, anonymous town, with small, anonymous descriptors. They seem to both live in and hover over the landscape. The important things are named and renamed, redefined as they change–or as the narrator’s perspective on them changes. Those named things become the notable landmarks of the novel, their evolution or transformation or renaming emblematic of the narrator’s own journey and perspective on those around him.

Lawler says it explicitly: “Our stories repeat themselves endlessly around us–ultimately revising who we are every time.”

It feels at once like reading the same chapter over and over again with certain words replaced, but this heightens the effect of those changed words and phrases. The same photograph, with things just a little older, a little changed. We begin in “the year they named the streets after the elements,” moves into “the year my parents began speaking in a strange language” and “the year we practiced for emergencies.” By the end, the repeated frameworks have become as nostalgic as old photos — in them, we see the history of all the shifts the narrator and the reader have together experienced. And in the rare deviations, we see the narrator looking beyond, departing: “‘This is where we are,’ he said, but his mouth was filled with uncertainty.”

The reader is forced to consider her own story in patterns and revisions, in names and malleable perspectives. I consider my own: The year that smelled of pool water and talcum powder. The year our neighbor’s daughter asked Santa for a penis. The year I drove in circles hoping to get lost, and failing. How best to crystallize time and experience in ways that approximate truth.

Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds is a poet’s fiction, but it’s an artist’s fiction too—because the brevity and economy of language makes the act of reading this novel something beyond reading, because the entire work seems to meditate on how we live in words, how we cohabitate with them in our daily routines and use them as mile-markers for landscapes past. How eventually, we become symbols of the lives we live, and how the uncertainty of detail grants us room to explore. - Jennifer Dane Clements

https://asitoughttobe.com/2013/12/23/a-review-of-patrick-lawlers-rescuers-of-skydivers-search-among-the-clouds/

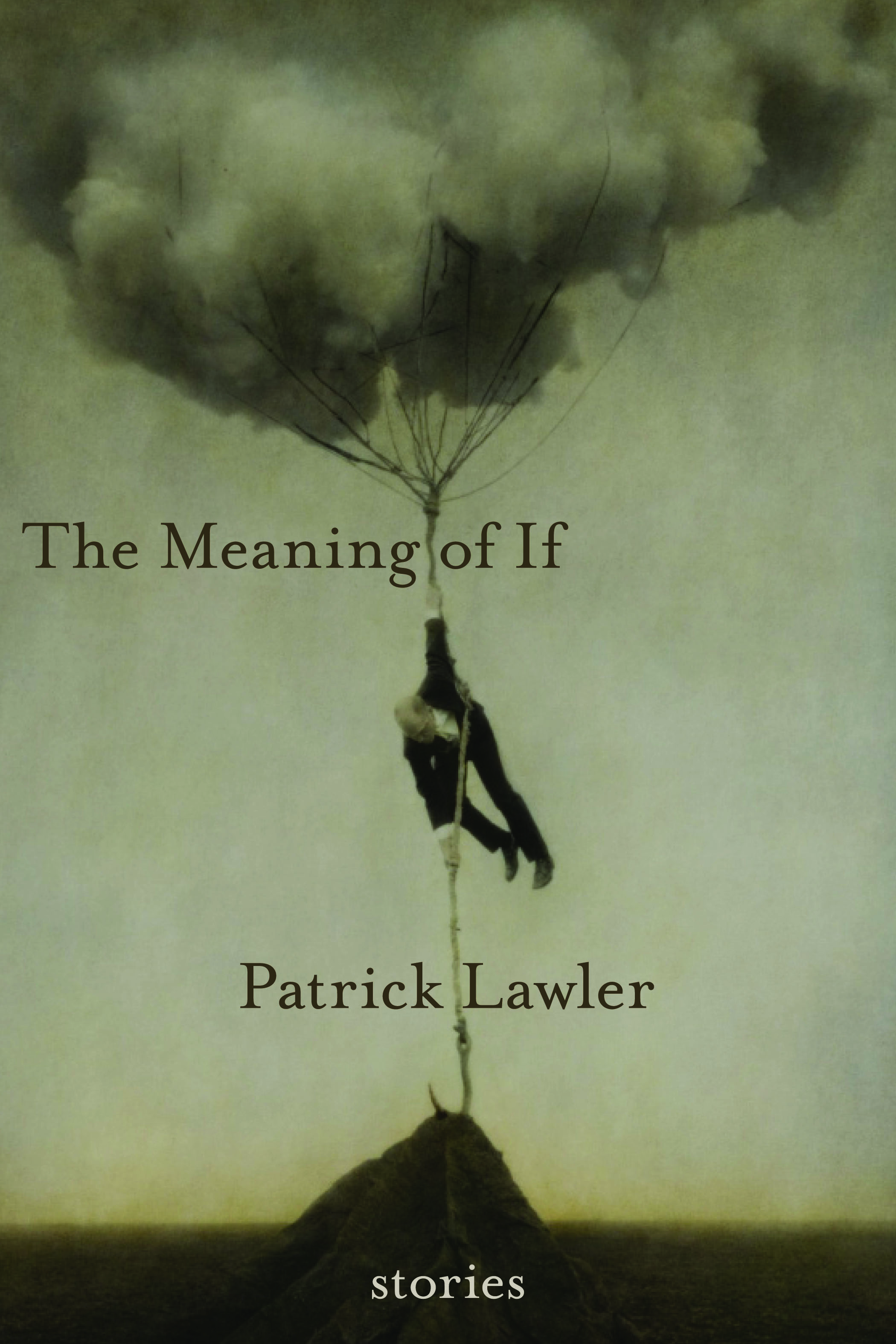

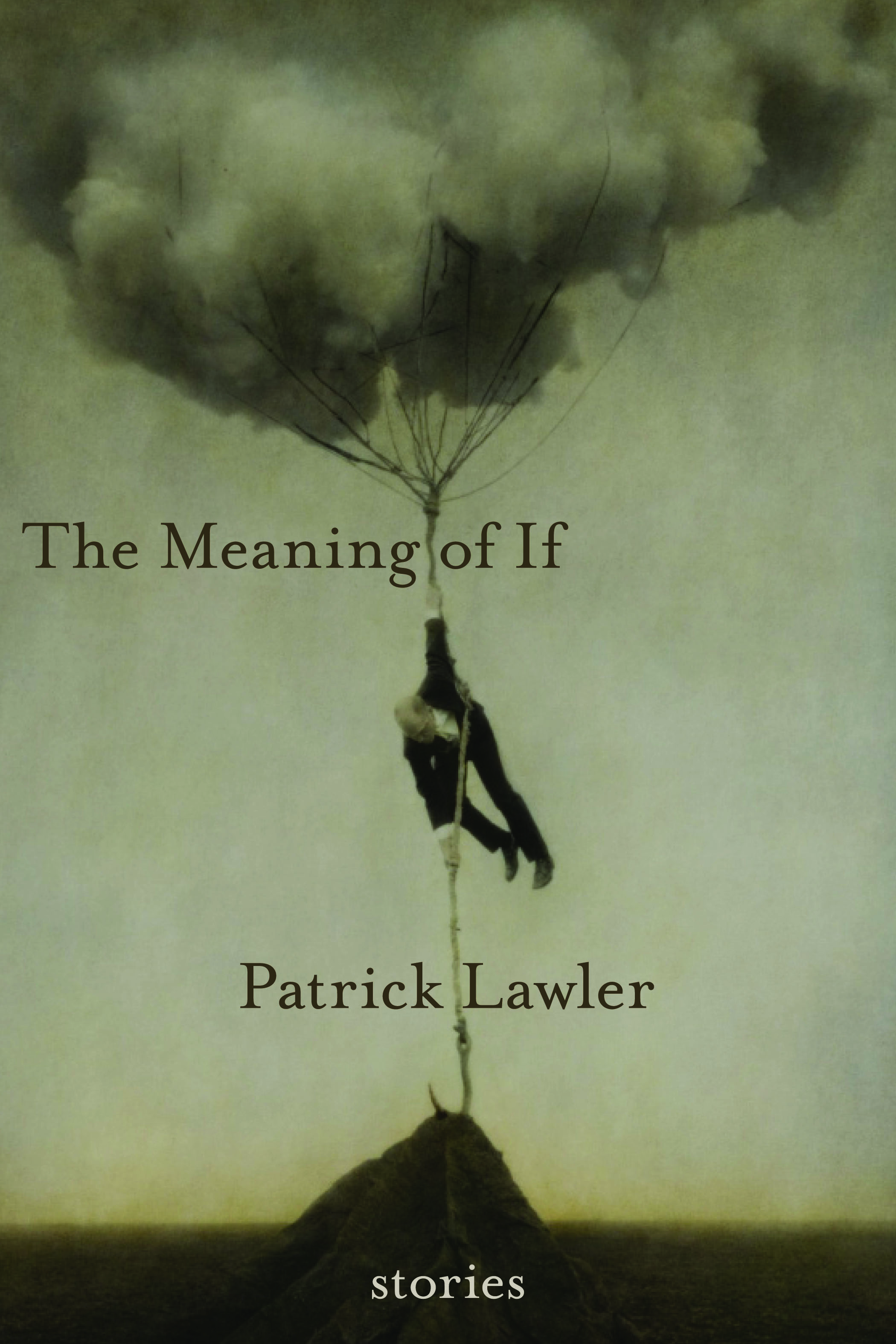

Patrick Lawler, The Meaning of If, Four Way, 2014.

“You just have to admire all the possibilities,” says one character in Patrick Lawler’s short story collection, The Meaning of If—a sentence that encapsulates the myriad of “if’s” explored in these pages. At times surreal and yet so realistic, we hear each “muffled whisper,” we see each “muddy photograph,” we know each “secret life,” as if it were our own. These are familial stories of transition and transformation—both mental and physical—that consider the question “What if?”

“Patrick Lawler is a word magician–he waves a wand and the ordinary glows and vibrates. Up his sleeve you’ll find Borges and Kafka. From his top hat he pulls out Nabokov and Marquez. But the Lawler show is completely his own: prepare to be dazzled as this master storyteller conjures up pain, joy, awe, and yearning so intensely, they feel like new experiences. With their unique poetic inventiveness, the stories of Patrick Lawler's The Meaning of If announce a new force in American short fiction.”- David Lloyd

“Patrick Lawler’s great gift as a storyteller is his utterly convincing vision of the absurd. With magician’s glee, these stories expose the vanities of small town America and the pathos of family life. The Meaning of If is a wild carnival ride; look, listen, and prepare to be exhilarated.”- Megan Staffel

From “When the Trees Speak”:There is no way I could handle the cutting, the dragging, the stacking. And to suggest my sister would be involved is certainly absurd. She’s got more on her mind. And why would I arrange the logs in a self-incriminating way? I personally feel that would be ridiculous. Why would I leave my name at the scene of the crime–if that’s what you want to call it? None of it makes much sense, but especially that part.

Should I speak louder or anything? I mean, is this thing on? I don’t want to have to do this again. OK, I guess this is my statement. That’s it, right? First, let me say I didn’t do it. And second, I don’t know who did. That should be the end of it–but I know how people talk, so I just want to set the record straight. Though you should know this: I wouldn’t be upset if the person never got caught. Nothing against you, Ike. I mean, I know you got a job to do–protecting people and like that. But I got my job, too. Not as important in some ways, but in some other ways it’s more important. Helping to put a roof over people’s heads is nothing to look down at.

Should I speak louder or anything? I mean, is this thing on? I don’t want to have to do this again. OK, I guess this is my statement. That’s it, right? First, let me say I didn’t do it. And second, I don’t know who did. That should be the end of it–but I know how people talk, so I just want to set the record straight. Though you should know this: I wouldn’t be upset if the person never got caught. Nothing against you, Ike. I mean, I know you got a job to do–protecting people and like that. But I got my job, too. Not as important in some ways, but in some other ways it’s more important. Helping to put a roof over people’s heads is nothing to look down at.

Patrick Lawler, Feeding the Fear of the Earth, Many Mountains Moving Press, 2006.

FEEDING THE FEAR OF THE EARTH is an outrageously original collection," Susan Terris writes of the Many Mountains Moving Poetry Book Contest winner. "Reaching across time and space and cultures and genders, Patrick Lawler gathers characters as diverse as Christopher Smart, Ed McMahon, and Rosa Parks. Ecological and ethereal, political and historical, philosophical and physical, this astonishing book is a place where anyone who has walked the earth can rub up against anyone else" - Linda Tomol

Patrick Lawler, Underground (Notes Toward an Autobiography), Many Mountains Moving Press, 2011.

"Patrick Lawler's new book UNDERGROUND (NOTES TOWARD AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY) is a unique and fascinating volume: part interview, part poetry, part elegy for his father, part examination of how a son with this particular father became a writer and a poet. You will be in awe at how Lawler, a boy who spent seven years living with his family in a cellar with no books—just a magic word box—transformed himself and came to terms with his father's idiosynchrasies as well as his own. 'At One of my Father's Funerals, I was Humphrey Bogart' is a knockout piece! Read this, read it all. Find out how Lawler discovers that an ending 'blossoms into multiple beginnings.'"—Susan Terris

Underground was published by a small press called Many Mountain Moving Press, which seems to be the one-man operation of Jeffrey Ethan Lee. Unexpectedly, I found myself quite affected by the book, which is, indeed, a sort of memoir, or more precisely, the account of a father rendered by a son. Unexpectedly, since generally I am quite suspicious of any rendering of world or word into binaries, such as dark/light; interior/exterior; above/beneath; shadow/sun, etc. For some reason, I accepted such tropes in the context of this book, a fact that I am still mulling over. Underground is structured as an alternation between an interview with the author by Paul B. Roth that appeared in Bitter Oleander in 2009 and selections of Lawler's poetry (these seem to date from the 1990s to the present). Although Underground is already a hybrid-genre text (poems, interview, a few photos, bio of father, bio of author), strangely enough, I felt myself wanting it to go even further in that direction. I found the alternation between interview sections and poems a bit too predictable.

When the author chose the title Underground, he was not using a metaphor. For, as he states at the beginning of the interview with Paul Roth: "As a child I lived in a cellar for seven years. We had intended to live in a house like everyone else, but my father broke his back and only the cellar was finished." (5) The cellar (the beneath) and the father (broken) are the two primary concerns or motifs of the book.

There's much language in Underground that I found appealing & evocative. The following is but a sample:

"but my destiny was to be a root."

"I'd take out/ the thin insides of pens for veins."

"I leave the rivers running all night."

"I watched things die around my father's hands."

"The ashtray crisscrossed with songlines" - P. Koneazny

Patrick Lawler, (reading a burning book), BASFAL Books, 1994.

This, Patrick Lawler's second book-length collection, is his follow-up to the critically praised A Drowning Man Is Never Tall Enough, and affirmation that he is truly one of the up and coming poets of his generation. Restricted by nothing, he lives on the edge without hesitation or fear. He is a poet for our time.

How lovely, to find poetry where I should never have thought to find anything of the kind. Imagine a book with a tarnished title, further soiled by the parenthesis in which it appears. Imagine, in the same vein, that this book is issued by a publisher with the unlucky designation Basfal Books. Now you have what I had when I first laid eyes on (reading a burning book), words already weary unto death with their preening in the lower case. But then one has oneself a look inside at what Mr. Patrick Lawler has wrought -- and sees, blasing back, very life, burning and burning, the mind prudently, but never anxiously, watchful in the shade. Thank God, thank God -- here is a poet. - Gordon Lish

Leaving "the mystery intact in every clue," Lawler's first book exposes, shocks and stirs us. - Newsday

In the case of Patrick Lawler, however, verbal brilliance is put in the service of deep philosophic probing...- Booklist

[A Drowning Man Is Never Tall Enough] is the genuine thing, not imitative but full of its own humilities and hubris, as all great literature is. The book is a wonder. - Bin Ramke

I'm given all sorts of pleasure by such immediate poems as "The Front," such skills as inform "Is (Is Not)," such structural accomplishments as "Stone Music," and -- clearly -- the progressions of the whole final section. - Philip Booth

Patrick Lawler, A Drowning Man Is Never Tall Enough, University of Georgia Press, 1990.

Patrick Lawler, A Drowning Man Is Never Tall Enough, University of Georgia Press, 1990.Patrick Lawler moves into the slender lines of shattered glass, the spaces between lyric and narrative, between metamorphosis and mutation. From the artful surface of a Russian novel, rich with symbolism and white bears, to a survivor's unwillingness to immerse himself in life or leave it, the poems in A Drowning Man Is Never Tall Enough hunger for a language beyond the solid, for the fragmentation that makes a scene complete.

Brilliance in poetry isn't always to be coveted; sometimes a poet is so blinded by the gorgeous phrase that meaning seems irrelevant—a feeling the reader rarely shares. In the case of Patrick Lawler, however, verbal brilliance is put in the service of deep philosophic probing: the question is 'how to distinguish / evil from benign absurdity' in a world where the 'dark dream names' of wars are brought to us nightly in 'talking light.' The poet, struck with the loss of moral certainty, finds even language slips away from what it tries to pin down... This fine first book should appeal to readers who share Lawler's concern for the moral and the real. - Booklist

I've heard a few of Lawler's public reads, and I browsed through an interview he once had, and I was impressed. Then I got lucky. I had him as a professor at college in a creative writing and poetry class, and I got a chance to speak with the mysterious man. I expected this genius to arrive in a suit; prim and proper with his hair slicked back, holding an attitude of superiority. I was in for a rude awakening. He dressed casually, acted casually, and I thought he was instead an average Joe who lucked out with a book or two. Wrong again. He walked into class and treated every person there as if we had all been old friends, and we held strange conversations of how to paint sculptures, and how a single word can say so much in a poem. He blew us all out of the water with his casualty and spunk. Patrick Lawler is a genius, as a teacher AND as a writer, but mostly as a person. After he revealed a bit of his life to class, I couldn't help but to be intrigued. I asked to have an interview with him, and now I realize there is a method to the madness. I understand now why he is who he is, and how he created such masterful pieces. After growing up in a cellar, and having an alcoholic father who broke his back and wore a strange brace was a perfect inspiration for Lawler's poetry. His life is far from boring. Lawler is a strange man that chooses to hide behind the scenes of a small college hoping to go by unnoticed, but he deserves to be put high on a pedestal and be praised for his work, and this set of poetry he has created in A Drowning Man is Never Tall Enough is just a small bite out of the life and times of the hidden genius that is Patrick Lawler. Thank you for everything Professor Lawler. - Eden J. Gideon

The Zeno Question by Patrick Lawler

2 POEMS

story Love Letter to Loon Lake: Electrical the Embryo (2017)

story Maps (2014)Patrick Lawler has four poetry collections: A Drowning Man is Never Tall Enough, reading a burning book, Feeding the Fear of the Earth, and Underground (Notes Toward an Autobiography). He teaches at SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry and is Writer-in-Residence at LeMoyne College.