One day before his seventy-second birthday, Wense died in a small attic apartment in the university town of Göttingen. He was nearly unknown to the literary and arts community, yet he left behind a magnificent legacy and would come to be considered one of the most eccentric, radical, and enigmatic literary figures of his generation. At the time of his death his apartment housed what could be described as a personal atlas—the charting of a life in letters, the mapping of a mind in an archive of numerous diaries and scrapbooks, hundreds of annotated survey maps and musical compositions, three thousand photographs, six thousand letters, and thirty thousand loose sheets of writings. These loose sheets contained his writings on natural history, mineralogy, astrology, astronomy, poetry, folklore, and music, to name but a few of the many subjects that formed the bedrock of his life and work. From these splinters I build my firm land, wrote Wense as a footnote in a letter to Wilhelm Niemeyer, and there was indeed an entire world in his room. His writings were filed in hundreds of binders, arranged alphabetically, and comprised three major works: Epidot, a collection of fragments and aphorisms; the Wanderbuch, on landscape and walking; and the All-book, an encyclopedia that was to be a total inventory of the earth.

A brilliant polymath, Wense planned to create the All-book from his extensive multidisciplinary research and writings. An encyclopedia arranged by keyword, it would collate his aphorisms, adaptations, and translations from more than one hundred languages, including those of the Middle East, Africa, Asia, South America, and Oceania. It would also include his detailed interpretations of the myths, poetry, and philosophy of ancient cultures. The folders for the All-book, as well as for the Wanderbuch and Epidot, were in a constant state of reworking and regrouping, part of an endless process of editing and expansion. They functioned as an archive and included the most minimal traces, excerpts, bibliographic information, newspaper clippings, apercus, marginalia, preliminary studies, and title-brief jottings. Wense considered and embraced everything—from a register of the items in the bedchamber of Alcibiades to a text fragment on singing crickets and a treatise on earwax. As Wense scholar and archivist Reiner Niehoff has noted, the library was Wense’s true birthplace. This great outsider of German literature carried his ecstasies of reading from the library into nature, and from there—in a wondrous mixture of pantheistic scribal-obsession, analytical ordinal-fury, and flight of ideas—back into his own works.

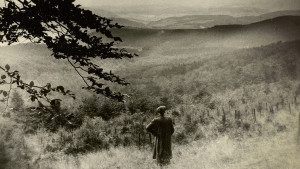

Wense’s move to Kassel in 1932 marked the beginning of his life as an ecstatic wanderer and writer of the Wanderbuch. The move was precipitated by a life-changing event—his discovery of the Hessian and Westphalian highlands, a landscape for which he was to develop a deep and lasting love. Wense had seen the Desenberg—a striking elevation in an otherwise predominantly flat and treeless landscape—by chance, during a railway journey, and the impression overwhelmed him to such a degree that he decided immediately to move to Middle Germany. The rest of his life would be dedicated to a comprehensive and profound survey of the landscape between the “poles” of Soest, Hildesheim, Eschwege, and Marburg. The Wanderbuch was to be a survey of this landscape in the greatest of detail—micro-territorial reappraisals of closest proximity. A radical, tireless, nearly obsessive walker (not unlike his Swiss contemporary Robert Walser or German compatriot W. G. Sebald), Wense averaged ten to twelve hours of hiking each day. He pushed himself physically to the very limit, covering great distances at a rapid pace, and was known to walk up to 40 kilometers a day. It is believed that he walked nearly 42,000 kilometers, or the equivalent of once around the earth, within just one hundred square kilometers of the Highlands. Consequently, he experienced intense states of exhaustion. His walks and methods were a mixture of geologic acumen and metaphysical drunkenness—as he attempted to place meteorological and geophysical phenomena in relation to cosmic ones. He transformed the traversed landscape with scientific precision into script. He roamed the land in order to become invisible.

A Shelter for Bells is the first book of Jürgen von der Wense’s writings published in English.

...A brilliant polymath and radical genius, like Artaud, Nietzsche, or Mahler, Wense lived among libraries and landscapes, without academic or familial consolations—often in near poverty—but canopied by his fever-longing to excavate and share the forgotten splendor of the things of this world. Radical, also, in his wandering, Wense is believed to have walked nearly 42,000 kilometers, or the equivalent of once around the earth, within just one hundred square kilometers of the Hessian and Westphalian highlands.

I first discovered his writings through a small book titled Epidot, which was published by the legendary German Publisher Axel Matthes in 1987. Further extracts from Wense’s universe would very slowly follow over the next decades, through the tireless efforts of Dieter Heim (Wense’s close friend and the executor of his estate), Matthes & Seitz, and Blauwerke. There is, in his work, no ivory tower scenario, no flight from living, but instead the will to see, at any cost, the radiant truth of the universe, which he wanted to inventory in its totality—in its most natural state. Hans Jürgen von der Wense was to me the last, and dearest, in a great tradition of visionaries. A nomad between the various sciences, cultures, and literatures of the earth—he is a man who could have been invented by Borges. Yet he lived and was his own universe—marvelous and homeless as the storm.- Herbert Pföstl

Movements are not created, they only find each other. That something happens is only ... luck, an act of genius. God himself is permanently surprised. True art.

Biographies must become prophetic. Every life is a divination. Genius is a sacrifice, from which God foretells himself. The life of a genius is fragment, secret knowledge.

Flaws must enter the composition like poisons in medicine.

To be free means to be free from opinions. To be sociable with the stars above. To be rich from spending one's life. To embrace it with one's knowledge, to know it with one's heart.

Wisdom is a crisis.

Sudden happiness is a great loss, so we become sick, because it breaks our habits, unsettles our vanities, when we realize, how long we had been content with the platitudes of feeling.

This joy whisks me from my destiny.

Everything we experience is an answer.

What is noble about the sun is not her warmth but her distance.

We embrace the ocean when we drown.

Consolation: nature has no opinion of me.

People without love have no destiny, they only improvise. With the speed of a falling weight my destiny increases because of love.

The meaning and goad of navigation is the secret, to sail after the sun and to go down with her. The meaning of travel is religion. Wanderlust is our nobility: a marvelous striving without destination. Seafarers were the first aristocrats.

With Columbus begins the downfall. His high caravels, filled with mutineers and robbers: the image of rabble. He thought he found paradise, but every paradise was discovered by the devil.

The rainbow is the banner after the battle between the sky and earth.

A Shelter for Bells is the first time that Wense’s writings have been published in English. The selection offered here by Epidote Press (which is a limited printing of 500 copies), and translated by Kristofor Minta and Herbert Pföstl, is divided into six chapters with broad themes: On Weather and Wandering, On Landscape and Place, On the Celestial, On the Hidden Properties of Things, On Knowing and Being, and On Writing and Language. But even within each chapter specific ideas forming the themes that were occupying Wense’s mind come forward. In the chapter On Weather and Wandering,for instance, it is clear that Wense views his daily walks as prayer or meditations; he is keenly affected by everything he observes in nature around him. The editors alternate between longer passages that appear to be from Wense’s diary and shorter observations, poems or aphorisms that could be from diaries or letters or snippets of poems. None of the translations are dated or identified so these are my guesses:

Spring: seventeen degrees Celsius. In the cirrus, a burning ring extended around the sun. Crystal, Crystal! I lingered in my bay and beheld it. I went to the heath. A mighty wilderness. Birch and oak. Larks reveled above the moors. Small, black-dappled channels interrupted by naughty frogs. Wide clearings with the lost scent of anemones. Behind it always, the all-silencing sea. I cam to a noisy meadow with shrubs, and each one swayed a white, dew-spittled web, and in each web sat a sleeping spider.

And in the shorter entries, usually just two or three on a page, Wense is equally as philosophical about his interactions with nature:

I would like best to thrown all books to the side and go out into the wind and there find it all again, the enharmonic changes and tonal cadences of light, the entire landscape a shepherd’s song: Madrigal

I want to walk tomorrow. Wandering is praying. I want to become a human being pure as starlight.

Only that will remain which has the sky as its measure.

Wense’s obsession with walking, however, causes him pain and illness. He also spends a lot of time in solitude and both the physical ailments and loneliness are oftentimes mentioned throughout the six chapters.

My favorite selections are those included in On Knowing and Being and On Writing and Language. A page in one of these sections contains only one, powerful sentence: “The ultimate message is silence,” which struck me in a very personal way. These chapters are full of equally brief, poignant, thought-provoking aphorisms. His ideas on poetry are a particular standout:

True Poems have meaning, but not results, for poetry is modulation, and nothing is more poetic than mistaking.

Poems are spells, impenetrable like every core. Poems are prophecies, overheard voices.

Poems are the clouds above language.

The book can be read easily in one sitting, as I did yesterday as soon as it arrived in the post. Or it can be a nice coffee table or bedside book that one dips into every once in a while. This wonderful collection has given me enough of a taste for Wense’s writing to want more. I am especially hoping that his letters and poems will be translated into English. Or my daughter is starting high school in the fall and is going to learn German…

“Only that will remain which has the sky as its measure.”

“Weather is the only earthly power whose rule I shall tolerate.”

“Understand: My walks are pilgrimages.”

“Everything I know I have experienced in the free wind.”

“Life must be conjured. Each wandering is an incantation.”

“Because everything that is beautiful is also a spiritual pain.”

“The ultimate message is silence.”

--Hans Jurgen von der Wense, A Shelter for Bells (published in a lovely edition by Epidote Press)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.