Eugene Vodolazkin, The Aviator, Trans. by Lisa Hayden, Oneworld Publications, 2018.

From award-winning author Eugene Vodolazkin comes this poignant story of memory, love and loss spanning twentieth-century Russia A man wakes up in a hospital bed, with no idea who he is or how he came to be there. The only information the doctor shares with his patient is his name: Innokenty Petrovich Platonov. As memories slowly resurface, Innokenty begins to build a vivid picture of his former life as a young man in Russia in the early twentieth century, living through the turbulence of the Russian Revolution and its aftermath. But soon, only one question remains: how can he remember the start of the twentieth century, when the pills by his bedside were made in 1999? Reminiscent of the great works of twentieth-century Russian literature, with nods to Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Bulgakov’s The White Guard, The Aviator cements Vodolazkin’s position as the rising star of Russia’s literary scene.

Eugene Vodolazkin’s Авиатор (The Aviator) is the first of this year’s Big Book finalists that I read: though I’d sworn I’d wait to read The Aviator when I could get it in print, I happily accepted the final text of the book from Vodolazkin and read a short passage on my reader each evening. It made for particularly nice spring reading. Though I always prefer print reading over electronic, I have to admit that limiting myself to short sections (to avoid the eye and attention strain I seem to get when reading electronically) was a good way to both extend my enjoyment of the novel and to consider, over time, the ways Vodolazkin develops his story and main character, Innokentii Platonov. I’m sure I would have loved a good binge-read, too, but it wouldn’t have done justice to this meditative (I think that’s the word I’m looking for) novel.

I’m afraid this post won’t do the novel much justice, either. That’s not just because I loved The Aviator so much in ways that I can’t explain, other than by saying that some books just seem to go right to the head and/or the heart, a phenomenon I think most of you understand. Nor do I want to gush. Beyond all that, I’m going very light on details in this post because one of the reasons I enjoyed The Aviator so much is that Vodolazkin didn’t tell me much at all about the novel: I began reading with only one bit of background (which spoiled nothing whatsoever but that I won’t mention because I don’t have context) and I had no expectations whatsoever about plot, character, or anything else. If I’d known more, I wouldn’t have gasped, audibly, when I found out what caused Platonov’s rather unique condition.

On an analytical, big-picture level, I was pleased to see how nicely The Aviator dovetails with Vodolazkin’s Laurus (previous post) and Solovyov and Larionov (brief summary on a previous post), both of which I’ve already translated. What I’d previously called a diptych now feels like a solid triptych. Each book examines—from very different angles—history, events, and time, which has a tendency to spiral in Vodolazkin’s novels. Since I’m translating The Aviator now, it’s easy to remember what details come very early in the book so I don’t spoil anything. Or at least very much. And so, a few things…

The Aviator is written in journal form, beginning with an undated entry by a man who’s quickly identified as Innokentii Petrovich Platonov. He appears to be a hospital patient with amnesia. His doctor, a man named Geiger (whose nose hairs Platonov sees on the third page), suggests the journal as a method for resurrecting his memory. As the days pass, Platonov begins remembering bits of his past and his personal story: he’s fairly quick to remember he’s the same age as his century, which can quickly be identified as the twentieth. And his location quickly sets the book in St. Petersburg, something that feels wholly organic. That’s not just because of mentions of landmarks or of street names that evoke the past, but because there’s a whiff of that old Gogolian feeling (since Gogol’s not mentioned in the novel, perhaps this is ingrained in my thinking? or even somehow idiopathic?) that unusual things can and most likely will happen there. The novel also incorporates Petersburg poet Alexander Blok’s “The Aviator” (here in Russian and here in English).

Vodolazkin works in elements from many genres, including love story and murder mystery, touches of science fiction and history, as well as coming of age, plus the bonus of references to Robinson Crusoe, which I realized I’ve somehow never read (!). There’s a little bit of everything, but all that everything flows together (everything matters here) very, very smoothly, gathering speed as time, history, events, and people, too, in their way, spiral. Of course there’s humor (I can’t imagine Vodolazkin writing without humor) and an almost improbably suspenseful ending. Most of all, though, from the perspective of a translator spiraling through a first draft of The Aviator—each draft and (re)reading of a book and its translation has the feel of spiraling history for me, too—I’m enjoying the book as a portrait of how a person grows and develops, more than once.

Though I have dozens and dozens of electronic notations on my PDF that mark time stamps, telling dreams, bits of history, and curious details about Platonov’s neighbors, not to mention incidences of flying, I’m keeping those to myself, with the hope that you’ll read the book, too, either now in Russian or later, when translations begin coming out. That said, if you’d like more details about The Aviator, visit the Banke, Goumen & Smirnova Literary Agency’s page about the novel here; the book’s cover art, by Mikhail Shemyakin, also offers insight into what happens in the book. - Lisa Hayden Espenschade

Innokenty Petrovich Platonov wakes up in a hospital bed, unsure not only of where he is and why he is there but of who he is. There appears to be one doctor (and only one doctor), Dr. Geiger, and one nurse and only one nurse, Valentina. There do not appear to be any other patients. This is in itself mystifying for Innokenty. He has a fever, which the doctor is worried about, but the doctor refuses to tell him who he is and why he is there. Instead, he asks Innokenty to write down what he remembers.

Gradually, he starts remembering things. He first remembers the Lord’s Prayer. He seems to think that he may have been an aviator. He remembers the Kuokkala district of St. Petersburg, which, since 1948, has been called Repino. Other things come back, such as ration cards and queueing for rations – just after the Revolution. Then he remembers queueing in 1919 and talking to a friend who reminds him that they were both born in 1900.

Geiger finally confirms that he was born in 1900 and that he has been unconscious for a very long time. Geiger tells him about changes, such as space exploration. Then he notices the pills on his table. They have a date on them – 1999. This means that he is ninety-nine years old, yet seems to be only thirty.

Innokenty gradually recalls his life. His father was murdered by drunken sailors. After the Revolution, he and his mother lived in a house that had been subdivided into rooms for various families, with shared facilities. One of the room was occupied by Anastasia Sergeyevna Voronina, five years younger than him, and her father. Another room was occupied by Zaretsky, who worked in the sausage factory, from where he stole his evening meals. Innokenty and Anastasia fall in love and start an affair. Indeed, we have learned this for a while, while Innokenty tries to remember where he met Anastasia. - The Modern Novel read more here

Innokenty Petrovich Platonov wakes up in a hospital bed with no recollection of who he is or how he got there. He is tended by a single doctor, Doctor Geiger, who gives him a pencil and notebook and encourages him to write down his observations and memories. The notebook is thick, like a novel. How can Innokenty fill it if he cannot remember anything? But slowly the memories start to return, memories of childhood holidays at the beach, of life in the dacha, of the airfield and the aviators...and the island...it seems like some memories may be better left buried. He remembers that he is the same age as the century, born in 1900. But if that is the case, how is he still a young man when the pills by his bedside are dated 1999?

So begins The Aviator, which immediately draws the reader in with the mystery of who Innokenty is and how he managed to seemingly travel in time. His diary fluctuates between his current observations and old memories of pre-revolutionary Russia, concentrating more heavily on the latter. As the story progresses and we unravel the mystery of how Innokenty came to be in the modern world, the story focuses on his difficulties fitting in and becoming accustomed to what is essentially an alien environment for him.

The book raises some thought-provoking topics. Is there anyone still alive from his time period? Friends? Family? Or is Innokenty completely alone? How will he adjust to the technology of our modern world? To computers, or even something as simple as the humble ball-point pen? It is interesting how these themes are addressed, as it is revealed that the things Innokenty misses most are the small things; sights, smells and sounds that he will never hear again. The sense of loss is palpable; the slow realisation of his situation and subsequent wave of grief hit him like a sledgehammer.

The book is firmly in the Literary Fiction category, so don't expect an easy or straightforward read. A lot of the narrative is verbose and almost poetic in nature. As the story continues, Innokenty becomes fixated on the minutiae of life, which means that the path between the beginning and end of the story can be a long and winding one, with plenty of diversions along the way. As a reader, I did feel that my perseverance was rewarded, although some chapters did seem excessively wordy. It didn't help that the author uses the protagonist's three given names interchangeably throughout the text, which can easily cause confusion.

The book leaves the reader with a lot to think about after the final page. The ending is left purposely ambiguous so the we are left to fill in the gaps of how the story turns out. It's impossible to not imagine how WE would feel and react, propelled almost a century into our own future. Many thanks to the publishers for a unique and immersive read. Also thanks to the translators for bringing the story to life for a wider audience. - Louise Jones

www.thebookbag.co.uk/reviews/index.php?title=The_Aviator_by_Eugene_Vodolazkin_and_Lisa_Hayden_(Translator)

Eugene Vodolazkin’s engaging new novel opens with a mystery. The main character—Innokenty Petrovich Platonov—wakes up in a hospital ward in 1999 with no memory of who he is or how he came to be there. “Was he in an accident?” he asks. “One might say that,” the doctor answers carefully in response. Told that he must remember everything except his name and encouraged to use a journal to record the knowledge of his personal past that he recovers, Platonov begins a journey of self-discovery. Memories of the summer cottage life that defined his childhood, the death of his father, deprivation, arrests, and a terrible place of confinement in the far north return to him jumbled and out of sequence. Although he looks no more than thirty, he is, he gradually understands, as old as the century, a real Robinson Crusoe, cast ashore in a strange modern world that he does not understand and, as a result, feels fundamentally isolated from. And yet how exactly did he arrive in the post-Soviet era, transported apparently straight from the 1920s?

Those familiar with twentieth-century Russian history will delight in the swirl of memories that emerge over the course of the narrative. We clearly see places and moments in time that matter profoundly in Russian cultural memory, including Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary Petrograd and the Soviet Union’s most notorious early labor camp, Solovki. Platonov’s unique, temporally fractured biography gives him a broad perspective on Russian life: just as an aviator might survey an expanse from above, his memory arcs from the early Soviet period to the end of the twentieth century.

At its heart, The Aviator is a work of memory and forgetting that is about the hard work of knitting together and understanding a century in Russian history that seems in so many ways broken in its awfulness. What, the novel seems to ask us, is the connection between individual and collective memory? What matters more in our understanding of the past: major historical events or the small details of daily life such as sounds and smells that are so evocative of our personal experiences?

The Aviator has been ably translated by Lisa Hayden. The novel will hold special appeal for those with an interest in Russian history and for fans of literary mysteries. - Emily Johnson

Innokenty Petrovich Platonov does not know who he is. Confined to a bed in a mysterious location and attended only by a Russian German doctor named Geiger and by Nurse Valentina, Innokenty is told to write. Geiger insists that he recall all the important memories on his own. Slowly, the details of his life in the first half of the twentieth century return—his romance with Anastasia Voronina, the Great War, the Bolshevik Revolution, his sentencing to a labor camp. But when he notices the expiration date on a bottle of pills, he realizes that he is now alive in the year 1999, though he has the appearance of someone much younger.

Through Innokenty’s journal entries, the mystery of his fate is revealed. Later, Geiger and Anastasia’s granddaughter add their own journal entries to this intricate tapestry of history, science, and religion. The brutal reality of the Bolshevik Revolution is painted in the small frame of Innokenty’s life, but retains the same (and perhaps greater) force of wider, more grandiose narratives chronicling the upheaval. Lisa Hayden’s translation reads beautifully and carries the poignancy well.

In the vein of Dostoyevsky, religion here is not an enemy to be vanquished, but rather a consolation and a means of deciphering the mechanisms of the human mind and the world—seen and unseen. With grace and an attractive gentleness, Innokenty asserts his religious beliefs, and demonstrates his faith’s timelessness and enduring relevance. As a man outside his own time, he critiques many of modern society’s norms—particularly the obsession with advertising and sensationalist news—indictments that ring even more true in the years beyond 1999.

Draped in thoroughly Russian trappings, The Aviator speaks to common experience while soaring into realms that enfold the human drama below. - Meagan Logsdon

https://www.forewordreviews.com/reviews/the-aviator/

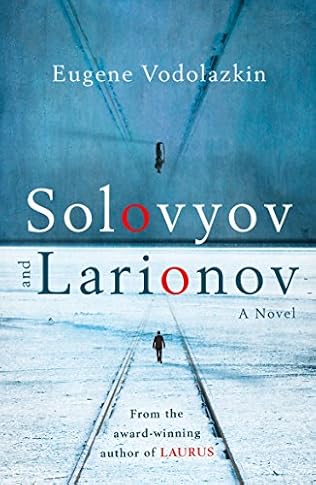

Eugene Vodolazkin, Solovyov and Larionov, Trans. by Lisa Hayden, Oneworld Publications, 2019.

Solovyov, a young scholar born into obscurity, arrives in St Petersburg to have his thesis topic handed to him: the story of General Larionov. Dismissive at first, his subject soon intrigues the young scholar, even obsesses him: this is no ordinary General. Not only did Larionov fight for the monarchist Whites during the Civil War, he did so with bloody distinction. So how did he manage to live unharmed in the Soviet Union, on a Soviet pension, cutting an imposing figure on the Yalta beaches, leaving behind a son and a volume of memoirs? The budding young historian sets off to Crimea to look for some lost pages from the General’s diary, and on his journey discovers many surprises, not least the charming Zoya, who works at Yalta’s Chekhov Museum.

With wry humour, philosophical seriousness and a ground-breaking narrative style, Solovyov and Larionov is a genre-defying historical detective novel that explores a fascinating period of Russian history.

Eugene Vodolazkin, Laurus, Trans. by Lisa C. Hayden, Oneworld Publications, 2015.

Fifteenth-century Russia

It is a time of plague and pestilence, and a young healer, skilled in the art of herbs and remedies, finds himself overcome with grief and guilt when he fails to save the one he holds closest to his heart. Leaving behind his village, his possessions and his name, he sets out on a quest for redemption, penniless and alone. But this is no ordinary journey: wandering across plague-ridden Europe, offering his healing powers to all in need, he travels through ages and countries, encountering a rich tapestry of wayfarers along the way. Accosted by highwaymen, lynched in Yugoslavia and washed overboard at sea, he eventually reaches Jerusalem, only to find his greatest challenge is yet to come.

“Brilliant storytelling ... a uniquely lavish, multilayered work.”—Booklist

“LAURUS is without a doubt one of the most moving and mysterious books you will read in this or any other year.”— The American Conservative

“An epic journey novel in all the best traditions. There are countless colorful characters, exciting twists of fate, and profound truths in the protagonist’s words and deeds… The Idiot meets Canterbury Tales meets The Odyssey. Highly recommended.”— Russian Life Magazine

"(A) nest of contradictions: a postmodern hagiography, at once stylistically ornate and compulsively readable, immersing the reader in meticulously detailed medieval Russian, Western European and Middle Eastern settings while consistently undermining them with contemporary insertions, as well as explicit assertions that historical time is inconsequential. (...) Many readers are likely to find the book enchanting, if not palliative." - Boris Dralyuk

Vodolazkin’s skill with language leaves a resonating after-effect. Good writers are able to peer through the lens of a particular time and space and stare into the infinite; Vodolazkin simultaneously embraces and rejects this image, often toying with the reader’s sense of spacial and temporal awareness. An expert in medieval history and folklore, he beautifully constructs scenes of fifteenth-century Russia and Europe, placing the reader in a timeless trance, before jerking the rug out from under your feet with such a reference as to a monastery located on the future Komsomol Square of Pskov.

The outcome of Vodolazkin’s constant construction and deconstruction of the typical framework gives a timeless quality to his characters and the themes that arise within Laurus. Indeed our protagonist Arensy embodies the mystical life of a saint that history glorifies: he lives on the fringe of life, feeling his actions occur both as a future experience and a past memory.

“Time truly was going backwards. It did

not accommodate the events designated for him—those events were

too grand and raucous. Time was coming apart at the seams, like a

wayfarer’s traveling bag, and it was showing its contents to the wayfarer,

who contemplated them as if for the first time.”

Vodolazkin jumps between archaic, medieval speech and contemporary slang, and interjects images of ancient Jerusalem with dreamscapes of Italy half a century later, envisioned by Arseny’s Florentine travel partner who is fixated on determining the certainty of the world’s end in the year 1500.

The pages, dotted with names of anachronistic herbs and forgotten family lineages – not to mention Vodolazkin’s complex interplay between modern and medieval Russian – do not make for a simple or smooth translation. Lisa Hayden should be commended for her effort, for she achieves just that. Subtly, she blends the familiar and unfamiliar, trusting the organic process through which the book unfolds and allowing the language to speak for itself.

Laurus excels in its reflective imagery. Love is shown through loss; death through agelessness; words through silence; the human in the divine. In life’s extremities, Vodolazkin has found a subtle balance and uses it to impressive effect. - Beau Lowenstern

https://www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/2015/10/08/whats-new-in-translation-october-2015/

Laurus is set in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century and is basically the birth-to-death story of its protagonist. A short introductory 'Prolegomenon' already summarizes it -- but, as the opening line noting: "He had four names at various times" suggests, there's more to it all.

Arseny was born in 1440, and he came to live with his grandfather, Christofer, when the plague came to the quarter where he lived with his parents, the disease quickly killing them off. A healer, Christofer passed on his medical and other knowledge to Arseny, a bright child who quickly picked things up. When Christofer died Arseny continued treating patients, showing a sure touch and feel for what ailed people and whether they could be cured -- and, if so, helping however he could.

A young woman, Utsina, appeared in his life -- fleeing from yet another plague-site. He took her in when no one else would, and they became a couple (though he tried not to reveal her presence in the house to outsiders, and although they didn't officially get married). She got pregnant -- but happy family life was not meant to be, leaving Arseny alone again. The loss of Utsina marks him for life: "I have an eternal love and eternal wife" he explains, even many years later, and Utsina remains a very real -- if not physical -- presence in his life.

Arseny left his hometown and on his travels revealed his healing-prowess, as he repeatedly came to places being ravaged by the plague and plunged right in, doing good. As happens repeatedly in his life, his reputation quickly spreads and people flock to him. Along the way he also found understanding benefactors, whether local grandees or nuns at a convent, who put up with his sometimes odd ways.

Arseny is taken for a 'holy fool' at times, but his diagnostic and healing touch is undeniable, as is his fundamental goodness -- a willingness to try to help wherever he can, even if that brings harm to him. He also has close calls under other circumstances, including on a journey to Jerusalem, which ends in yet another trauma that marks him for the remainder of his life. Arseny settles down for a while in a monastery, but eventually decides to find his place alone and elsewhere. Even in what should be complete isolation he can not escape those seeking his help, and he also takes in and cares for yet another young woman who can not remain at home.

Much of Arseny's life is relatively uneventful. He has a remarkable gift for understanding what ails people, recognizing it instantly and advising them accordingly (even unbidden). He is a great healer but he isn't entirely a miracle-worker; some ailments are beyond him. His self-sacrifice is impressive but also -- like much in the novel -- a sort of monotone: while the action sometimes takes unexpected turns, Arseny's actions and reactions remain predictably true to him, varying only to the extent of how self-absorbedly-contemplative he is, as there are numerous times he withdraws almost entirely into himself.

There's a pervasive sense of fatalism here: Arseny's diagnoses are quick, even abrupt, and if there's no hope then there is no hope. Death is omnipresent, especially with the plague repeatedly striking, but even aside from disease fatal accidents and violent deaths are near-everyday occurrences.

Arseny isn't a man of many words, but words do mean a great deal to him. He picks up reading quickly, and one of the things he does with Ustina as well as the final girl who becomes part of his life is teach them to read and write. His grandfather's books are important to him, and he seeks out others that provide more knowledge. Later in life, he spends time as a transcriptionist in the monastery.

Language matters in the novel, too, which frequently reverts to an older style and at times shifts over entirely in quoting from writing of that time. Much of the novel, both in language and story, has the feel of droning incantation -- and yet it never really bogs down in that. Even as Arseny's mundane and often repetitious actions are described, there is something compelling to it. Vodolazkin also remains anything but predictable, with occasional scenes from the future, including the twentieth century, suddenly cropping up, an effective disarming technique that also, somehow, seems fitting

Steeped in religion, Arseny is a character who is almost too good to believe, and his supernatural diagnostic and healing powers too simplistic. Yet for all that Laurus is a gripping, weirdly fascinating read -- very Russian, perhaps, in its fundamental outlooks and presentation, and certainly very carefully and well crafted (so also in Lisa Hayden's English rendering). - M.A.Orthofer

http://www.complete-review.com/reviews/russia/vodolazkin.htm

Love, faith, and a quest for atonement are the driving themes of an epic, prizewinning Russian novel that, while set in the medieval era, takes a contemporary look at the meaning of time.

Combining elements of fairy tale, parable, and myth, Vodolazkin’s second novel (after Solovyov and Larionov, to be published in English in 2016) is a picaresque story exploring 15th-century existence with gravity and a touch of ironic humor. Its language veers from archaic—"Bathe thyself, yf thou wylt"—to modern slang, and its preoccupations range across language and belief to herbalism and history. Binding all this together is a character whose name changes four times over his lifetime as he progresses through phases as healer, husband, holy fool, pilgrim, and hermit. Born in Russia in 1441, Arseny is an only child, raised by his wise grandfather Christofer after his parents die of plague. Discerning Arseny’s healing gifts, Christofer passes on to his grandson his knowledge of plants and remedies and his role as village healer. After Christofer’s death, Arseny’s loneliness is dispelled by the arrival of plague fugitive Ustina, but the eternal love that develops between them frightens Arseny and leads to failings which will haunt him for the rest of his life. Unobtrusively translated, the novel’s narration flows limpidly, touching humane depths, especially when depicting sickness, suffering, and death, which is often. Vodolazkin handles his long, unpredictable, sometimes-mystical saga and its diverse content with confident purpose, occasionally adding modern visions to the historical landscape, part of a conversation about discontinuous time. Traveling across Europe and Palestine and then back to Russia, Arseny, who will become Ustin, Amvrosy, and finally Laurus, will eventually complete his long, circular journey and reach a place of repose.

With flavors of Umberto Eco and The Canterbury Tales, this affecting, idiosyncratic novel, although sometimes baggy, is an impressive achievement. —Kirkus Reviews

Medieval Russia was a land trembling with religious fervor. Mystics, pilgrims, prophets, and holy fools wandered the countryside. Their wardrobe and grooming choices earned them names like Maksim the Naked and John the Hairy. Basil the Blessed walked through Moscow in rags, castigated the rich, exposed deceitful merchants, and issued prophecies, many of which proved correct, or close enough. St. Basil’s Cathedral in Red Square is named for him. Nil Sorsky was renowned for his asceticism and devotion, suggesting that, through self-discipline and prayer, you could directly commune with God, making irrelevant the extravagant rituals of Orthodoxy. Many ascetics were deemed “fools for Christ,” whether or not they behaved foolishly. Some were designated saints.

A new novel by the Russian medievalist Eugene Vodolazkin, “Laurus,” recreates this fervent landscape and suggests why the era, its holy men, and the forests and fields of Muscovy retain such a grip on the Russian imagination. Vodolazkin’s hero-mystic Arseny is a protagonist extrapolated from the little that is known about the lives and deeds of the famous holy men. Born in 1440, he’s raised by his herbalist grandfather Christofer near the grounds of the Kirillov Monastery, about three hundred miles north of Moscow. He becomes a renowned medicine man, faith healer, and prophet who “pelted demons with stones and conversed with angels.” He makes a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He takes on new names, depending on how he will next serve God. The people venerate his humble spirituality. In “Laurus,” Vodolazkin aims directly at the heart of the Russian religious experience and perhaps even at that maddeningly elusive concept that is cherished to the point of cliché: the Russian soul.

So much of that soul seems to be wrapped up in Russia’s relationship with the natural world: intimate but wary, occult but practical. Arseny’s initial renown comes from his success as an herbalist and healer as he employs what he learned from his beloved grandfather. For wart removal, the best treatment is a sprinkling of ground cornflower seeds. For burns, apply linen with ground cabbage and egg white. The white root of a plant called hare’s ear cures erectile dysfunction. (“The drawback to this method was that the white root had to be held in the mouth at the crucial moment.”) At least some of Arseny’s remedies are suspect. (Translator Lisa C. Hayden warns, “Please don’t try these at home.”)

The remedies invoke an idea of nature as essentially friendly, or at least potentially helpful. Folk medicine remains popular in Russia to this day. Whether or not it’s effective, it connects an overwhelmingly urbanized population to the scythed fields and profound, spirit-dwelling forests of its antiquity. And Vodolazkin takes his holy fools seriously, offering a view of medieval Christianity that goes well beyond the appropriation of home remedies for religious purposes. Although Arseny cherishes Christofer’s birch-bark pharmaceutical texts, he doesn’t believe the herbs are responsible when the ill recover. (Often, they don’t.) The keys are prayer and faith. He bows to icons on a shelf. Incense burns. A vitalizing current runs from his hands into the core of the patient’s suffering. In “Laurus,” the depiction of faith is presented entirely without irony—a strategy that has become unusual among literary writers, but which is central to Vodolazkin’s effort to excavate what was meaningful from Russia’s distant past.

IT’S HARD TO WRITE saintly characters. Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov is the least interesting of the brothers. Everybody reads the Inferno, but how many make it to Paradise? Yet Eugene Vodolazkin, whose second novel, Laurus, won both Russia’s Big Book and Yasnaya Polyana prizes in 2013, succeeds gloriously, giving us not just goodliness but an actual saint — a fictional wonderworker in the 15th century. A scholar of medieval literature at St. Petersburg’s Pushkin House, the Institute for Russian Literature, Vodolazkin propels us headlong into the strangeness and wonders of medieval Russia.

An orphan, Arseny, comes to live with his wise grandfather Christofer following the deaths of his parents in a remote part of Northern Russia. From Christofer, he is initiated into the folk healer’s practices, the secrets of the forest and its herbs, and knowledge of men through their weaknesses and sins. Early on, he reveals spiritual powers even beyond that of the old man:

The child thoughtfully kissed Saint Christopher on his shaggy head and touched the dulled paints with the pads of his fingers. His grandfather observed the icon’s mysterious current flow into Arseny’s hands.

In medieval times, the herb or remedy is only a conduit. The power of the healer lay in his connection with God. Christofer tells Arseny a seed held in the mouth is used to part water — when accompanied by prayer. Is it the seed or the prayer that accomplishes the act, Arseny wants to know. It’s all about the prayer, Christofer replies. The boy answers, “Then why do you need that seed?”

Following Christofer’s death, Arseny takes his place as the village healer. All goes well until the day a girl, Ustina, appears in the monastery cemetery, sole survivor of her village’s demise by plague. Arseny takes her in, and love enters the hut where only learning and selfless service had dwelled. But having begot a child with Ustina, Arseny reveals himself to be a possessive lover, while his confidence as a healer prevents him from calling the midwife. Worse yet, he dissuades Ustina from going to church for confession. When she dies in childbirth, he carries a double sin: responsibility for her and their child’s death, and for their unconfessed souls.

The novel is a treasure house of Russian medieval lore and customs, and Vodolazkin convinces us of the horrors awaiting the unconfessed dead. Not in the hereafter, but simply on earth. What to do with the bodies? They can’t be buried, only “heaped,” as the earth would spit them out again. Unburied, they are unable to find peace and cause poor harvests. If they were buried, people would dig them up when spring frosts harmed the crops. Buried, unburied, becoming exposed, piled, moved around — it was enough to drive even a saint mad. Thus, we understand perfectly why Arseny would forswear his settled life to hit the road and try to redeem Ustina’s soul through prayer and suffering.

Thus begins Arseny’s journey as mendicant healer, moving from village to village, indifferently exposing himself to plague, cold, and hunger, nameless and without destination, in the fine tradition of Russian mystics. Life is not about finding a place for ones’s self, but for one’s soul, one’s connection with spirit. He has, without realizing it, become that most Russian of all figures, the holy fool.

Arriving by boat in the great medieval city of Pskov, he is immediately accosted by long-time holy fool Foma, who gives Arseny (now called Ustin) the ground rules of holy fool turf wars, using another holy fool, Karp, as exemplar:

Did you know […] each part of the Pskov soil supports but one holy fool? […] [B]y inflicting bloody wounds on holy fool Karp, [I] induce him not to leave Zapskovye, the area beyond the Pskova. [… I teach him] Zapskovye would be like a lonesome orphan without you, and you’d create an excess of our sort in my part of town. And excess is depravity that leads to spiritual devastation.

Safe on the other side of the river, holy fool Karp shakes a fist at him. “Go ahead and threaten, you shithead,” Foma shouts back. “If I shall ever see thee here one daye, I will mercilessly smash your members. Like as the smoke vanisheth, so shall you be driven away.”

The fools are holy, but they also bash each other and defend turf. A great deal of the novel’s humor derives from this kind of absurd juxtaposition. On this earth, one can never quite break free of petty, ridiculous, earthly concerns. Even the ancient sage Christofer is regularly consulted about “bedroom matters.” Much of the humor in Dostoevsky has exactly this origin.

Equally rich are the novel’s clashes of language and diction, a savory stew made up of high and low, the ecclesiastical and the obscene, as well as the crazily modern. Translator Lisa Hayden had a tall order before her — Vodolazkin’s book in Russian overflows with Old Church Slavonic, contemporary slang, obscenities, bureaucratese, literary language. In translating, she avails herself of the contemporaneous Middle English Bible for much of the syntax and archaisms, but also a range of slang, curses, and other vocabularies. The result is a wonderful, at times almost Monty Python–esque blend of biblical vanisheth, synne, and pryde, right alongside shithead, jeez, and Brownian motion.

And so it becomes clear very early that Laurus is no seamless dream of Russia’s past, but a very clever, self-aware contemporary novel that nevertheless holds that dream deep in its heart:

The snow began melting in the middle of April and immediately looked old and shabby. […] Ustina no longer wanted a fur coat like that. She stepped from one melting hummock to another, cautiously watching her feet. All the forest’s grime had emerged from under the snow: last year’s foliage, pieces of rags that had lost their color, and yellowed plastic bottles.

Just as we’re happily sinking into a dream of herbs and forest lore, tame wolves, and grandfather Christofer’s wisdom inscribed on birch bark, those plastic bottles appear, like the Statue of Liberty peeking from the sands of the Planet of the Apes. Vodolazkin’s use of anachronisms such as “Brownian motion” and “shithead,” the visions of future foretold by the novel’s many prescient characters, all speak to our dilemma as modern inhabitants of a world made in — and of — the past. Underneath this medieval, mystical tale of the saintly healer, there’s an unrecycled present, suggesting the unity of time, past and future, as they would look in the eyes of a timeless being — say, God.

So Laurus is a quirky, ambitious book. In addition to the highly absorbing coming of saintdom in Arseny — healer, holy fool, pilgrim — and its “inside look” at Russian medieval customs and mystical tradition, its habits of mind, and embrace of the irrational and paradoxical which anyone who loves Dostoevsky will immediately recognize, Laurus is a modern, often comic novel nevertheless concerned with time and spirituality and the Russian soul as is perfectly embodied in the holy fools.

It’s a condition that embraces paradox: holy fools often behave perversely, doing what, to our earthly eyes, appears plain wrong. Some are mentally ill, but there is always sanity in their madness. Others are fools in the Shakespearean sense — unpredictable, unfathomable beings who have a special line on the truth, and are revered for their vision, treated with great respect, but also vulnerable, beaten, harassed, and even killed.

This is the paradox of the Russian soul. You can trace a straight line from these medieval times to Dostoevsky to the present era, the confluence of the brutal and the divine. In his story of the saint, Vodolazkin asks what life is, in the absence of saintliness or of a mystical flame, other than coarse and thoughtless existence. The book suggests that people still need the example of saints, and faith in miracles, to turn their attention to the life of the spirit.

The medieval period left a deep impact on Russian consciousness — far more than the Dark Ages did in the West. Christianity didn’t arrive in Rus’, the Russian world centered in Kiev, until around 1000 AD, and an inward-looking, spiritually oriented, medieval society took shape, which remained in place until Peter the Great artificially defibrillated it some seven centuries later. No Renaissance softened the blow, no secular humanism erased the memory of medieval life. As a result, Russian culture carries a lasting scent of its medieval past, into which Laurus vividly inaugurates us — a world rich with wonder and superstition, faith and foreboding, walled cities and plague and visions, impassible roads and holy fools.

Under the spell of Laurus, we imagine what it would be like to measure life in seasons and harvests rather than clocks and clicks, to walk in hallowed paths and receive ancient wisdom, to suffer and cleanse the soul. It deposits us, much like the 2007 Russian film The Island — about a man who becomes a contemporary holy fool — into a magical world steeped in voluntary suffering, devotion, and answered prayer, which stands in opposition to Western skepticism and aversion to irrationality.

Unlike a saintly figure one might find in other postmodern Russian work, Vodolazkin’s holy man and his medieval world are drawn with sincere, uncynical affection. As such, the novel embodies a break with immediate post-Soviet literature, which is heavily skeptical and leavened with irony. Laurus contains stylistic similarities to contemporary Russian works — the fracturing of time, the linguistic playfulness — but within the confines of a tale of faith. The result: an instructive saint’s life keyed for a sophisticated contemporary audience, and suggesting an alternative to materialism, irony, and despair.

The concern with the “Russian soul” and life of the spirit reemerges regularly in Russian culture — marked by a turning away from the West, the need to reestablish who we are in terms of who we were, and of how we differ from others. It’s not surprising, in these uncertain decades following the collapse of the Soviet Union, to see a book like Laurus take the big awards in Russia. The materialism that seized that country at the end of the Soviet Union left behind a spiritual hunger, and set the national identity adrift. Ironic literature can meet despair with a kind of gallows humor, but it doesn’t successfully address the deeper need. Laurus’s loving portrait of the medieval world and the holy man’s bildungsroman, couched in entertainingly playful postmodernist language, offers an enticing alternative to contemporary cynicism. And we in the West might also consider the extent to which longing for such certitudes might be surfacing within us, like an old water bottle under the snow. - Janet Fitch

lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-russian-soul-janet-fitch-on-eugene-vodolazkin/

Winner of two of the biggest literary prizes in Russia, Laurus is a remarkably rich novel about the eternal themes of love, loss, self-sacrifice and faith, from one of the country's most experimental and critically acclaimed novelists.

“Brilliant storytelling ... a uniquely lavish, multilayered work.”—Booklist

“LAURUS is without a doubt one of the most moving and mysterious books you will read in this or any other year.”— The American Conservative

“An epic journey novel in all the best traditions. There are countless colorful characters, exciting twists of fate, and profound truths in the protagonist’s words and deeds… The Idiot meets Canterbury Tales meets The Odyssey. Highly recommended.”— Russian Life Magazine

"(A) nest of contradictions: a postmodern hagiography, at once stylistically ornate and compulsively readable, immersing the reader in meticulously detailed medieval Russian, Western European and Middle Eastern settings while consistently undermining them with contemporary insertions, as well as explicit assertions that historical time is inconsequential. (...) Many readers are likely to find the book enchanting, if not palliative." - Boris Dralyuk

Laurus, the second novel by Russian writer Eugene Vodolazkin (after Solovyov and Larionov, due to appear in English in 2016), is in one breath, a timeless epic, trekking the well-trodden fields of faith, love, and the infinite depth of loss and search for meaning. In another, it is pointed, touching, and at times humorous, unpredictably straying from the path and leading readers along a wild chase through time, language, and medieval Europe. Winner of both the National Big Book Prize (Russia) and the Yasnaya Polyana Award, Vodolazkin’s experimental style envelopes the reader, drawing them into a world far from their own, yet indescribably intimate.

Spanning late fifteenth-century Russia to early twentieth-century Italy, the novel recounts the multiple lives (or stages of life) of a saint and the story of his becoming. Born Arseny in 1440, he is raised by his grandfather after his parents die from the plague that torments much of Russia and Europe. Recognising the boy’s gift for healing, his grandfather instills in him knowledge of healing and herbalism. Arseny aids the pestilence-stricken villagers, yet his powers of healing are overshadowed by his helplessness in preventing his grandfather’s death, as well as the passing of his beloved Ustina. Abandoning his village, past and namesake, Arseny begins a voyage that will transcend country and identity. Kaleidoscopic in his language and reach, Vodolazkin takes us on a journey of discovery and absolution, threaded together through the various, often mystical lives of Arseny as a healer, husband, holy fool, pilgrim and hermit.Vodolazkin’s skill with language leaves a resonating after-effect. Good writers are able to peer through the lens of a particular time and space and stare into the infinite; Vodolazkin simultaneously embraces and rejects this image, often toying with the reader’s sense of spacial and temporal awareness. An expert in medieval history and folklore, he beautifully constructs scenes of fifteenth-century Russia and Europe, placing the reader in a timeless trance, before jerking the rug out from under your feet with such a reference as to a monastery located on the future Komsomol Square of Pskov.

The outcome of Vodolazkin’s constant construction and deconstruction of the typical framework gives a timeless quality to his characters and the themes that arise within Laurus. Indeed our protagonist Arensy embodies the mystical life of a saint that history glorifies: he lives on the fringe of life, feeling his actions occur both as a future experience and a past memory.

“Time truly was going backwards. It did

not accommodate the events designated for him—those events were

too grand and raucous. Time was coming apart at the seams, like a

wayfarer’s traveling bag, and it was showing its contents to the wayfarer,

who contemplated them as if for the first time.”

Vodolazkin jumps between archaic, medieval speech and contemporary slang, and interjects images of ancient Jerusalem with dreamscapes of Italy half a century later, envisioned by Arseny’s Florentine travel partner who is fixated on determining the certainty of the world’s end in the year 1500.

The pages, dotted with names of anachronistic herbs and forgotten family lineages – not to mention Vodolazkin’s complex interplay between modern and medieval Russian – do not make for a simple or smooth translation. Lisa Hayden should be commended for her effort, for she achieves just that. Subtly, she blends the familiar and unfamiliar, trusting the organic process through which the book unfolds and allowing the language to speak for itself.

Laurus excels in its reflective imagery. Love is shown through loss; death through agelessness; words through silence; the human in the divine. In life’s extremities, Vodolazkin has found a subtle balance and uses it to impressive effect. - Beau Lowenstern

https://www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/2015/10/08/whats-new-in-translation-october-2015/

Laurus is set in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century and is basically the birth-to-death story of its protagonist. A short introductory 'Prolegomenon' already summarizes it -- but, as the opening line noting: "He had four names at various times" suggests, there's more to it all.

Arseny was born in 1440, and he came to live with his grandfather, Christofer, when the plague came to the quarter where he lived with his parents, the disease quickly killing them off. A healer, Christofer passed on his medical and other knowledge to Arseny, a bright child who quickly picked things up. When Christofer died Arseny continued treating patients, showing a sure touch and feel for what ailed people and whether they could be cured -- and, if so, helping however he could.

A young woman, Utsina, appeared in his life -- fleeing from yet another plague-site. He took her in when no one else would, and they became a couple (though he tried not to reveal her presence in the house to outsiders, and although they didn't officially get married). She got pregnant -- but happy family life was not meant to be, leaving Arseny alone again. The loss of Utsina marks him for life: "I have an eternal love and eternal wife" he explains, even many years later, and Utsina remains a very real -- if not physical -- presence in his life.

Arseny left his hometown and on his travels revealed his healing-prowess, as he repeatedly came to places being ravaged by the plague and plunged right in, doing good. As happens repeatedly in his life, his reputation quickly spreads and people flock to him. Along the way he also found understanding benefactors, whether local grandees or nuns at a convent, who put up with his sometimes odd ways.

Arseny is taken for a 'holy fool' at times, but his diagnostic and healing touch is undeniable, as is his fundamental goodness -- a willingness to try to help wherever he can, even if that brings harm to him. He also has close calls under other circumstances, including on a journey to Jerusalem, which ends in yet another trauma that marks him for the remainder of his life. Arseny settles down for a while in a monastery, but eventually decides to find his place alone and elsewhere. Even in what should be complete isolation he can not escape those seeking his help, and he also takes in and cares for yet another young woman who can not remain at home.

Much of Arseny's life is relatively uneventful. He has a remarkable gift for understanding what ails people, recognizing it instantly and advising them accordingly (even unbidden). He is a great healer but he isn't entirely a miracle-worker; some ailments are beyond him. His self-sacrifice is impressive but also -- like much in the novel -- a sort of monotone: while the action sometimes takes unexpected turns, Arseny's actions and reactions remain predictably true to him, varying only to the extent of how self-absorbedly-contemplative he is, as there are numerous times he withdraws almost entirely into himself.

There's a pervasive sense of fatalism here: Arseny's diagnoses are quick, even abrupt, and if there's no hope then there is no hope. Death is omnipresent, especially with the plague repeatedly striking, but even aside from disease fatal accidents and violent deaths are near-everyday occurrences.

Arseny isn't a man of many words, but words do mean a great deal to him. He picks up reading quickly, and one of the things he does with Ustina as well as the final girl who becomes part of his life is teach them to read and write. His grandfather's books are important to him, and he seeks out others that provide more knowledge. Later in life, he spends time as a transcriptionist in the monastery.

Language matters in the novel, too, which frequently reverts to an older style and at times shifts over entirely in quoting from writing of that time. Much of the novel, both in language and story, has the feel of droning incantation -- and yet it never really bogs down in that. Even as Arseny's mundane and often repetitious actions are described, there is something compelling to it. Vodolazkin also remains anything but predictable, with occasional scenes from the future, including the twentieth century, suddenly cropping up, an effective disarming technique that also, somehow, seems fitting

Steeped in religion, Arseny is a character who is almost too good to believe, and his supernatural diagnostic and healing powers too simplistic. Yet for all that Laurus is a gripping, weirdly fascinating read -- very Russian, perhaps, in its fundamental outlooks and presentation, and certainly very carefully and well crafted (so also in Lisa Hayden's English rendering). - M.A.Orthofer

http://www.complete-review.com/reviews/russia/vodolazkin.htm

Love, faith, and a quest for atonement are the driving themes of an epic, prizewinning Russian novel that, while set in the medieval era, takes a contemporary look at the meaning of time.

Combining elements of fairy tale, parable, and myth, Vodolazkin’s second novel (after Solovyov and Larionov, to be published in English in 2016) is a picaresque story exploring 15th-century existence with gravity and a touch of ironic humor. Its language veers from archaic—"Bathe thyself, yf thou wylt"—to modern slang, and its preoccupations range across language and belief to herbalism and history. Binding all this together is a character whose name changes four times over his lifetime as he progresses through phases as healer, husband, holy fool, pilgrim, and hermit. Born in Russia in 1441, Arseny is an only child, raised by his wise grandfather Christofer after his parents die of plague. Discerning Arseny’s healing gifts, Christofer passes on to his grandson his knowledge of plants and remedies and his role as village healer. After Christofer’s death, Arseny’s loneliness is dispelled by the arrival of plague fugitive Ustina, but the eternal love that develops between them frightens Arseny and leads to failings which will haunt him for the rest of his life. Unobtrusively translated, the novel’s narration flows limpidly, touching humane depths, especially when depicting sickness, suffering, and death, which is often. Vodolazkin handles his long, unpredictable, sometimes-mystical saga and its diverse content with confident purpose, occasionally adding modern visions to the historical landscape, part of a conversation about discontinuous time. Traveling across Europe and Palestine and then back to Russia, Arseny, who will become Ustin, Amvrosy, and finally Laurus, will eventually complete his long, circular journey and reach a place of repose.

With flavors of Umberto Eco and The Canterbury Tales, this affecting, idiosyncratic novel, although sometimes baggy, is an impressive achievement. —Kirkus Reviews

Medieval Russia was a land trembling with religious fervor. Mystics, pilgrims, prophets, and holy fools wandered the countryside. Their wardrobe and grooming choices earned them names like Maksim the Naked and John the Hairy. Basil the Blessed walked through Moscow in rags, castigated the rich, exposed deceitful merchants, and issued prophecies, many of which proved correct, or close enough. St. Basil’s Cathedral in Red Square is named for him. Nil Sorsky was renowned for his asceticism and devotion, suggesting that, through self-discipline and prayer, you could directly commune with God, making irrelevant the extravagant rituals of Orthodoxy. Many ascetics were deemed “fools for Christ,” whether or not they behaved foolishly. Some were designated saints.

A new novel by the Russian medievalist Eugene Vodolazkin, “Laurus,” recreates this fervent landscape and suggests why the era, its holy men, and the forests and fields of Muscovy retain such a grip on the Russian imagination. Vodolazkin’s hero-mystic Arseny is a protagonist extrapolated from the little that is known about the lives and deeds of the famous holy men. Born in 1440, he’s raised by his herbalist grandfather Christofer near the grounds of the Kirillov Monastery, about three hundred miles north of Moscow. He becomes a renowned medicine man, faith healer, and prophet who “pelted demons with stones and conversed with angels.” He makes a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He takes on new names, depending on how he will next serve God. The people venerate his humble spirituality. In “Laurus,” Vodolazkin aims directly at the heart of the Russian religious experience and perhaps even at that maddeningly elusive concept that is cherished to the point of cliché: the Russian soul.

So much of that soul seems to be wrapped up in Russia’s relationship with the natural world: intimate but wary, occult but practical. Arseny’s initial renown comes from his success as an herbalist and healer as he employs what he learned from his beloved grandfather. For wart removal, the best treatment is a sprinkling of ground cornflower seeds. For burns, apply linen with ground cabbage and egg white. The white root of a plant called hare’s ear cures erectile dysfunction. (“The drawback to this method was that the white root had to be held in the mouth at the crucial moment.”) At least some of Arseny’s remedies are suspect. (Translator Lisa C. Hayden warns, “Please don’t try these at home.”)

The remedies invoke an idea of nature as essentially friendly, or at least potentially helpful. Folk medicine remains popular in Russia to this day. Whether or not it’s effective, it connects an overwhelmingly urbanized population to the scythed fields and profound, spirit-dwelling forests of its antiquity. And Vodolazkin takes his holy fools seriously, offering a view of medieval Christianity that goes well beyond the appropriation of home remedies for religious purposes. Although Arseny cherishes Christofer’s birch-bark pharmaceutical texts, he doesn’t believe the herbs are responsible when the ill recover. (Often, they don’t.) The keys are prayer and faith. He bows to icons on a shelf. Incense burns. A vitalizing current runs from his hands into the core of the patient’s suffering. In “Laurus,” the depiction of faith is presented entirely without irony—a strategy that has become unusual among literary writers, but which is central to Vodolazkin’s effort to excavate what was meaningful from Russia’s distant past.

The faith of Vodolazkin’s holy fools is neither ecstatic, like many forms of Western Christianity, nor hierarchical, like Eastern Christianity, nor scholarly, like Judaism. Although the Greek-derived word doesn’t appear in “Laurus,” Arseny appears to embrace “Hesychasm,” the Byzantine religious movement in pursuit of inner peace. In his magisterial history of Russian culture, “The Icon and the Axe,” James H. Billington explains that the Hesychasts received “divine illumination” through “ascetic discipline of the flesh and silent prayers of the spirit.” This often required years of isolation and silence. Arseny accepts the challenge after a series of trials, most significantly the death of his beloved Ustina, a young woman who had found refuge in his log house after her family was lost to the plague. His botched attempt to deliver their child tests the limits of prayer and folk medicine: “The blood was flowing from the womb and he could not stanch it. He took some finely grated cinnabar in his fingers and went as deeply into Ustina’s female places as he could.” Arseny acknowledges his malpractice, but not the fact that she’s gone forever. Shattered by her death, he journeys to the town of Pskov, in what was then Lithuania. He spends decades without speaking, and is designated one of the region’s three holy fools. Most of his silent communion is not with God, but with Ustina’s spirit.

The other element of being a Russian holy man was a taste for prophecy—”dominating all other manifestations of eccentric sanctity,” according to Sergei Ivanov, author of “Holy Fools in Byzantium and Beyond,” the most authoritative English-language account of the phenomenon. “For many holy fools the power to predict is virtually the only quality mentioned in the sources.” Arseny looks at the ill and knows, regardless of his ministrations, who will survive and who will die. As a boy fool-in-training, he peers into the fire of the stove and sees the image of an elderly man. The aged Arseny will gaze into another fire at the unlined face of himself as a boy.

With so many of the blessed running around, fifteenth-century Russia, as Vodolazkin depicts it, is the golden age of prophets. Similarly ragged and unkempt, they stand at the entrances of markets. They appear at christenings and weep for the truncated lives they foretell. They sleep in cemeteries. Since there are seven days in the week, they figure that God has ordained seven millennia of human existence. Thus they widely announce that the world will end seven thousand years after its creation in 5508 B.C.—in other words, in A.D. 1492, just around the corner. Beset by plague and pestilence, poverty and hunger, the Russians already sense themselves on the brink of annihilation. They’re receptive. In the West, especially in Spain, other Christians similarly anticipate the apocalypse.

Arseny’s Italian friend Ambrogio, who has come to Russia because of its hospitality to prophets, predicts floods to the day; he can also see within a Soviet linen shop, circa 1951. But his visions of 1492 are confused. “On the one hand, a new continent would be discovered, on the other, the end of the world was expected in Rus’.” Ambrogio joins Arseny for his journey to Jerusalem. Passing through Poland, on their way to the Mediterranean, the two holy men reach the small town of Oświęcim. Ambrogio says, “Believe me, O Arseny, this place will induce horrors in centuries. But its gravity can be felt, even now.” - Ken Kalfus

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/holy-foolery

The other element of being a Russian holy man was a taste for prophecy—”dominating all other manifestations of eccentric sanctity,” according to Sergei Ivanov, author of “Holy Fools in Byzantium and Beyond,” the most authoritative English-language account of the phenomenon. “For many holy fools the power to predict is virtually the only quality mentioned in the sources.” Arseny looks at the ill and knows, regardless of his ministrations, who will survive and who will die. As a boy fool-in-training, he peers into the fire of the stove and sees the image of an elderly man. The aged Arseny will gaze into another fire at the unlined face of himself as a boy.

With so many of the blessed running around, fifteenth-century Russia, as Vodolazkin depicts it, is the golden age of prophets. Similarly ragged and unkempt, they stand at the entrances of markets. They appear at christenings and weep for the truncated lives they foretell. They sleep in cemeteries. Since there are seven days in the week, they figure that God has ordained seven millennia of human existence. Thus they widely announce that the world will end seven thousand years after its creation in 5508 B.C.—in other words, in A.D. 1492, just around the corner. Beset by plague and pestilence, poverty and hunger, the Russians already sense themselves on the brink of annihilation. They’re receptive. In the West, especially in Spain, other Christians similarly anticipate the apocalypse.

Arseny’s Italian friend Ambrogio, who has come to Russia because of its hospitality to prophets, predicts floods to the day; he can also see within a Soviet linen shop, circa 1951. But his visions of 1492 are confused. “On the one hand, a new continent would be discovered, on the other, the end of the world was expected in Rus’.” Ambrogio joins Arseny for his journey to Jerusalem. Passing through Poland, on their way to the Mediterranean, the two holy men reach the small town of Oświęcim. Ambrogio says, “Believe me, O Arseny, this place will induce horrors in centuries. But its gravity can be felt, even now.” - Ken Kalfus

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/holy-foolery

IT’S HARD TO WRITE saintly characters. Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov is the least interesting of the brothers. Everybody reads the Inferno, but how many make it to Paradise? Yet Eugene Vodolazkin, whose second novel, Laurus, won both Russia’s Big Book and Yasnaya Polyana prizes in 2013, succeeds gloriously, giving us not just goodliness but an actual saint — a fictional wonderworker in the 15th century. A scholar of medieval literature at St. Petersburg’s Pushkin House, the Institute for Russian Literature, Vodolazkin propels us headlong into the strangeness and wonders of medieval Russia.

An orphan, Arseny, comes to live with his wise grandfather Christofer following the deaths of his parents in a remote part of Northern Russia. From Christofer, he is initiated into the folk healer’s practices, the secrets of the forest and its herbs, and knowledge of men through their weaknesses and sins. Early on, he reveals spiritual powers even beyond that of the old man:

The child thoughtfully kissed Saint Christopher on his shaggy head and touched the dulled paints with the pads of his fingers. His grandfather observed the icon’s mysterious current flow into Arseny’s hands.

In medieval times, the herb or remedy is only a conduit. The power of the healer lay in his connection with God. Christofer tells Arseny a seed held in the mouth is used to part water — when accompanied by prayer. Is it the seed or the prayer that accomplishes the act, Arseny wants to know. It’s all about the prayer, Christofer replies. The boy answers, “Then why do you need that seed?”

Following Christofer’s death, Arseny takes his place as the village healer. All goes well until the day a girl, Ustina, appears in the monastery cemetery, sole survivor of her village’s demise by plague. Arseny takes her in, and love enters the hut where only learning and selfless service had dwelled. But having begot a child with Ustina, Arseny reveals himself to be a possessive lover, while his confidence as a healer prevents him from calling the midwife. Worse yet, he dissuades Ustina from going to church for confession. When she dies in childbirth, he carries a double sin: responsibility for her and their child’s death, and for their unconfessed souls.

The novel is a treasure house of Russian medieval lore and customs, and Vodolazkin convinces us of the horrors awaiting the unconfessed dead. Not in the hereafter, but simply on earth. What to do with the bodies? They can’t be buried, only “heaped,” as the earth would spit them out again. Unburied, they are unable to find peace and cause poor harvests. If they were buried, people would dig them up when spring frosts harmed the crops. Buried, unburied, becoming exposed, piled, moved around — it was enough to drive even a saint mad. Thus, we understand perfectly why Arseny would forswear his settled life to hit the road and try to redeem Ustina’s soul through prayer and suffering.

Thus begins Arseny’s journey as mendicant healer, moving from village to village, indifferently exposing himself to plague, cold, and hunger, nameless and without destination, in the fine tradition of Russian mystics. Life is not about finding a place for ones’s self, but for one’s soul, one’s connection with spirit. He has, without realizing it, become that most Russian of all figures, the holy fool.

Arriving by boat in the great medieval city of Pskov, he is immediately accosted by long-time holy fool Foma, who gives Arseny (now called Ustin) the ground rules of holy fool turf wars, using another holy fool, Karp, as exemplar:

Did you know […] each part of the Pskov soil supports but one holy fool? […] [B]y inflicting bloody wounds on holy fool Karp, [I] induce him not to leave Zapskovye, the area beyond the Pskova. [… I teach him] Zapskovye would be like a lonesome orphan without you, and you’d create an excess of our sort in my part of town. And excess is depravity that leads to spiritual devastation.

Safe on the other side of the river, holy fool Karp shakes a fist at him. “Go ahead and threaten, you shithead,” Foma shouts back. “If I shall ever see thee here one daye, I will mercilessly smash your members. Like as the smoke vanisheth, so shall you be driven away.”

The fools are holy, but they also bash each other and defend turf. A great deal of the novel’s humor derives from this kind of absurd juxtaposition. On this earth, one can never quite break free of petty, ridiculous, earthly concerns. Even the ancient sage Christofer is regularly consulted about “bedroom matters.” Much of the humor in Dostoevsky has exactly this origin.

Equally rich are the novel’s clashes of language and diction, a savory stew made up of high and low, the ecclesiastical and the obscene, as well as the crazily modern. Translator Lisa Hayden had a tall order before her — Vodolazkin’s book in Russian overflows with Old Church Slavonic, contemporary slang, obscenities, bureaucratese, literary language. In translating, she avails herself of the contemporaneous Middle English Bible for much of the syntax and archaisms, but also a range of slang, curses, and other vocabularies. The result is a wonderful, at times almost Monty Python–esque blend of biblical vanisheth, synne, and pryde, right alongside shithead, jeez, and Brownian motion.

And so it becomes clear very early that Laurus is no seamless dream of Russia’s past, but a very clever, self-aware contemporary novel that nevertheless holds that dream deep in its heart:

The snow began melting in the middle of April and immediately looked old and shabby. […] Ustina no longer wanted a fur coat like that. She stepped from one melting hummock to another, cautiously watching her feet. All the forest’s grime had emerged from under the snow: last year’s foliage, pieces of rags that had lost their color, and yellowed plastic bottles.

Just as we’re happily sinking into a dream of herbs and forest lore, tame wolves, and grandfather Christofer’s wisdom inscribed on birch bark, those plastic bottles appear, like the Statue of Liberty peeking from the sands of the Planet of the Apes. Vodolazkin’s use of anachronisms such as “Brownian motion” and “shithead,” the visions of future foretold by the novel’s many prescient characters, all speak to our dilemma as modern inhabitants of a world made in — and of — the past. Underneath this medieval, mystical tale of the saintly healer, there’s an unrecycled present, suggesting the unity of time, past and future, as they would look in the eyes of a timeless being — say, God.

So Laurus is a quirky, ambitious book. In addition to the highly absorbing coming of saintdom in Arseny — healer, holy fool, pilgrim — and its “inside look” at Russian medieval customs and mystical tradition, its habits of mind, and embrace of the irrational and paradoxical which anyone who loves Dostoevsky will immediately recognize, Laurus is a modern, often comic novel nevertheless concerned with time and spirituality and the Russian soul as is perfectly embodied in the holy fools.

It’s a condition that embraces paradox: holy fools often behave perversely, doing what, to our earthly eyes, appears plain wrong. Some are mentally ill, but there is always sanity in their madness. Others are fools in the Shakespearean sense — unpredictable, unfathomable beings who have a special line on the truth, and are revered for their vision, treated with great respect, but also vulnerable, beaten, harassed, and even killed.

This is the paradox of the Russian soul. You can trace a straight line from these medieval times to Dostoevsky to the present era, the confluence of the brutal and the divine. In his story of the saint, Vodolazkin asks what life is, in the absence of saintliness or of a mystical flame, other than coarse and thoughtless existence. The book suggests that people still need the example of saints, and faith in miracles, to turn their attention to the life of the spirit.

The medieval period left a deep impact on Russian consciousness — far more than the Dark Ages did in the West. Christianity didn’t arrive in Rus’, the Russian world centered in Kiev, until around 1000 AD, and an inward-looking, spiritually oriented, medieval society took shape, which remained in place until Peter the Great artificially defibrillated it some seven centuries later. No Renaissance softened the blow, no secular humanism erased the memory of medieval life. As a result, Russian culture carries a lasting scent of its medieval past, into which Laurus vividly inaugurates us — a world rich with wonder and superstition, faith and foreboding, walled cities and plague and visions, impassible roads and holy fools.

Under the spell of Laurus, we imagine what it would be like to measure life in seasons and harvests rather than clocks and clicks, to walk in hallowed paths and receive ancient wisdom, to suffer and cleanse the soul. It deposits us, much like the 2007 Russian film The Island — about a man who becomes a contemporary holy fool — into a magical world steeped in voluntary suffering, devotion, and answered prayer, which stands in opposition to Western skepticism and aversion to irrationality.

Unlike a saintly figure one might find in other postmodern Russian work, Vodolazkin’s holy man and his medieval world are drawn with sincere, uncynical affection. As such, the novel embodies a break with immediate post-Soviet literature, which is heavily skeptical and leavened with irony. Laurus contains stylistic similarities to contemporary Russian works — the fracturing of time, the linguistic playfulness — but within the confines of a tale of faith. The result: an instructive saint’s life keyed for a sophisticated contemporary audience, and suggesting an alternative to materialism, irony, and despair.

The concern with the “Russian soul” and life of the spirit reemerges regularly in Russian culture — marked by a turning away from the West, the need to reestablish who we are in terms of who we were, and of how we differ from others. It’s not surprising, in these uncertain decades following the collapse of the Soviet Union, to see a book like Laurus take the big awards in Russia. The materialism that seized that country at the end of the Soviet Union left behind a spiritual hunger, and set the national identity adrift. Ironic literature can meet despair with a kind of gallows humor, but it doesn’t successfully address the deeper need. Laurus’s loving portrait of the medieval world and the holy man’s bildungsroman, couched in entertainingly playful postmodernist language, offers an enticing alternative to contemporary cynicism. And we in the West might also consider the extent to which longing for such certitudes might be surfacing within us, like an old water bottle under the snow. - Janet Fitch

lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-russian-soul-janet-fitch-on-eugene-vodolazkin/

Laurus, the second novel by Russian writer Eugene Vodolazkin, has a vivid sense of time and place, as you might expect from an author who is also an expert in medieval history. Interweaving an impressive array of images, stories, parables and superstitions, Vodolazkin builds a convincing portrait of 15th-century Europe, a God-fearing place riven by disease and hardship. Yet he also conveys a very contemporary sense of the contingency of identity and of the malleability of time. Little wonder that he has been compared to Umberto Eco, whose The Name of the Rose (1980) cleverly melded postmodern sensibilities with a medieval setting.The book’s eponymous hero is a healer who, in the course of his life, becomes a pilgrim, holy fool and hermit; in each of the four sections, he takes on a new identity. He is born in Rus in 1440 and christened Arseny. After losing his parents to the plague, he is raised by his grandfather, a herbalist who teaches the boy about the healing power of plants. They enjoy a quiet, simple life, and Arseny learns to read and write.

After his grandfather’s death, 15-year-old Arseny remains in rural seclusion, serving as the village doctor. His feelings of emptiness are relieved only by the arrival of Ustina, a young woman carrying the plague. He cures her and they enjoy a brief but intense happiness until her death in childbirth. Unmarried, and wishing to keep her existence a secret because of their “living in sin”, Arseny had refused to find a midwife to help Ustina deliver the stillborn child. Grief-and guilt-stricken, he travels from village to village treating people through prayer and his healing hands.

Divine idiocy is a recurring theme in Russian literature, where the distinction between sanity and madness is deliberately blurred. On reaching Pskov, in the far west, Arseny resolves “to forget everything and live from now on as if there had been nothing in my life before, as if I had just appeared on earth right now”. He becomes a holy fool, residing in the town cemetery for 14 years — “the earthe as a bed, the heavens as a roof”. He throws stones at pious people’s houses — he can see the devils gathered outside, unable to enter — and kisses the walls of a sinner’s home, by which the exiled angels shelter. As Vodolazkin wrote in a 2013 essay, “Contemporary Russia desperately needs people who can pelt devils with stones, but even more, it needs those who can talk with angels.” Perhaps the jury that awarded Laurus Russia’s prestigious Big Book Prize in 2013 felt the same.

Throughout the novel there is an impending sense of doom. Many of the characters Arseny encounters believe that the apocalypse is nigh. One of those attempting to calculate the exact date is Ambrogio, a young Italian whose passion for history is matched by his startling visions of the future. Ambrogio meets Arseny in Pskov and they become travelling companions on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Sharing an emotional and intellectual bond, they survive encounters with highwaymen, a trek through the Alps and a storm at sea.

As an old man, Arseny, now named Laurus, muses that “life resembles a mosaic that scatters into pieces”. Vodolazkin’s work is a similar montage of scenes. Humanity, history and culture collide, observed from different perspectives. He also writes with wry humour about his fellow countrymen. “You Russians really like talking about death,” a merchant chides Arseny and Ambrogio, “And it distracts you from getting on with your lives.”

Laurus spends his last years in a forest cave near the Rukina Quarter, his childhood home. Here, he loses all sense of time, aware only of the passing seasons; indeed, he concludes that time is discontinuous, that its “individual parts were not connected to one another, much as there was no connection between the blond little boy from Rukina Quarter . . . and the gray-haired wayfarer, almost an old man [that he now is]”. The sense of fracture is reflected in Vodolazkin’s style, which blends archaisms, modern slang and passages from medieval texts.

Given such complexity, the fluidity of Lisa Hayden’s English translation is commendable. Though some readers may be deterred by the archaic flourishes and sometimes fable-like narrative, Laurus cannot be faulted for its ambition or for its poignant humanity. It is a profound, sometimes challenging, meditation on faith, love and life’s mysteries. - Lucy Popescu

https://www.ft.com/content/ae5a830c-83e8-11e5-8e80-1574112844fd

After his grandfather’s death, 15-year-old Arseny remains in rural seclusion, serving as the village doctor. His feelings of emptiness are relieved only by the arrival of Ustina, a young woman carrying the plague. He cures her and they enjoy a brief but intense happiness until her death in childbirth. Unmarried, and wishing to keep her existence a secret because of their “living in sin”, Arseny had refused to find a midwife to help Ustina deliver the stillborn child. Grief-and guilt-stricken, he travels from village to village treating people through prayer and his healing hands.

Divine idiocy is a recurring theme in Russian literature, where the distinction between sanity and madness is deliberately blurred. On reaching Pskov, in the far west, Arseny resolves “to forget everything and live from now on as if there had been nothing in my life before, as if I had just appeared on earth right now”. He becomes a holy fool, residing in the town cemetery for 14 years — “the earthe as a bed, the heavens as a roof”. He throws stones at pious people’s houses — he can see the devils gathered outside, unable to enter — and kisses the walls of a sinner’s home, by which the exiled angels shelter. As Vodolazkin wrote in a 2013 essay, “Contemporary Russia desperately needs people who can pelt devils with stones, but even more, it needs those who can talk with angels.” Perhaps the jury that awarded Laurus Russia’s prestigious Big Book Prize in 2013 felt the same.