Germán Espinosa, La Tejedora de coronas [Te Weaver of Crowns], 1982.

By renowned author, it is considered a masterpiece and one of the most important works in Colombian literature. Now in its 19th edition, many have placed it along side of award winning novel One Hundred Years of Solitude. ". . . one of the most beautiful books of Latin American Literature of this century". -La République des Lettres, Paris.

It’s not every day you discover a literary masterpiece

The first remarkable thing about this book is the way it is written. If you are fond of long meandering sentences of Lazslo Krazsnohorkai and W.G. Sebald, or if you have enjoyed reading Matthias Énard’s single-sentence lyrical exploration of war

Born in the coastal city of Cartagena (present-day Colombia), Genoveva is destined to leave her homeland for France in the company of two geographers who later prove to be members of the Masonic Lodge. When reaching Europe, Genoveva starts an impressive career of a scientist, adventurer and secret agent, which impels her to visit different countries carrying out special assignments of the Lodge, like establishing its subsidiary in Spain or persuading George Washington to head resistance against the British colonial rule in America. Not all her trips have a political agenda. For example, Genoveva travels to Lapland as a member of Maupertuis’ expedition whose goal is to measure a meridian arc near the North Pole. Being as insatiable for carnal pleasures as for knowledge, Genoveva drifts from one lover to another, never settling on one particular man. One of the most significant affairs in her life is a fling with young poet François-Marie Arouet who comes to be known to the world under the pen name Voltaire. Actually, it is thanks to the rebellious philosopher and writer that she is introduced to the secret activities of Freemasons. Being an open-minded and inquisitive woman, Genoveva imbibes the revolutionary ideas of the leading proponents of the Enlightenment and, in her turn, tries to promote their views all the way to her native shores in the Caribbean. Genoveva is fascinated by all sorts of knowledge, be it politics, science, art or literature. No matter how dire her situation is, this passion for learning never leaves her. Thus, while imprisoned in the formidable Bastille for taking part in a mock Satanic ritual enacted to distract the attention of the Parisian police from the Lodge authorities meeting Emmanuel Swedenborg, she makes use of the decade-long incarceration to read the essential works of world literature . The following passage brilliantly characterises Genoveva’s capacity for learning, and will surely resonate with any devoted reader:

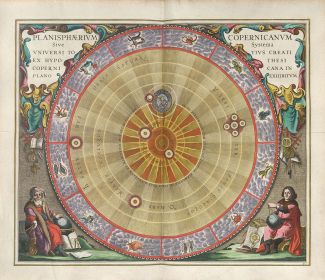

in German I read the Minnisingers, the Mestersingers, and von Haller, in Italian Dante and Petrarca, in Spanish my old favourites, romances de gesta, Manrique, San Juan de La Cruz, fray Luis, Garcilaso, Góngora and Quevedo, in French rather an extensive list of books, how to enumerate all of them? from the beautiful Roman de la rose, to Rutebeuf, Chretien de Troyes, Jaufré Rudel, Pierre de Ronsard, Charles d’Orléans, […] in English I became fascinated by the incomparable powers of a certain William Shakespeare […]How can a simple girl from a far-away Spanish colony in the Indies become such a learned person? Genoveva partly owes her insatiable appetite for knowledge to the young self-taught astronomer Federico Goltar, her childhood friend with whom she predictably falls in love. The adolescent turns the enclosed balcony of his house into an astronomical observatory that he crams with measuring instruments, armillary spheres, maps and scientific treatises. The young stargazer’s credo is encapsulated by the plate from Cellarius’ Harmonia Macrocosmica representing the planisphere of Copernicus which he nails to the wall.

When Federico isn’t engrossed in studying maps, atlases or cosmograms, he peers into the sky through his telescope in search of new celestial bodies. And indeed, one day he discovers a new planet which he names after his beloved. The green planet Genoveva, known to us as Uranus, becomes a symbol of their youthful love which is not meant to consummate. Everything is changed by the single tragic event that turns the lives of Cartagena’s inhabitants upside down. The 1697 raid on the fortified city by the French Navy in conjunction with a motley crew of Tortuga buccaneers is the black hole in the fabric of Genoveva’s story around which the accretion disk of all the other events in her life will be always spinning. As a result of a secret deal between the governor of Cartagena and the French admiral Baron de Pointis, the wealthy merchant city is surrendered to the plundering troops of King Louis XIV. When the French fleet leaves Cartagena without sharing the spoils with the pirates, the buccaneers rampage through its streets in an orgy of pillage, murder and rape. Throughout her story Genoveva keeps returning to these horrifying events, each time coming closer to the bloodcurdling denouement alluded to earlier in the novel, but graphically described only near the end. When the Spanish rule is re-established in Cartagena, Genoveva, who has already lost friends and relatives during the raid, is faced with the ultimate loss: Federico is wrongly accused of treason and executed together with other similar victims, all of which is part of the scheme employed by governor Diego de Los Ríos to divert suspicion from his dirty dealings with the French aggressors. Federico’s dream of going to the educated France to continue his scientific research as well as to present the discovery of the green planet now can come true only vicariously – through Genoveva.

In the 14 years that elapse since the fateful raid until her encounter with the two geographers, Pascal de Bignon and Guido Aldrovandi, Genoveva further educates herself in mathematics, geography and astronomy making use of the scientific treatises she inherits from Federico. Thanks to this formidable knowledge she is employed by Aldrovandi and de Bignon, who take her on their geodesic mission in Quito. After that, she accompanies them to France. There, in the course of the busy years of serving the Lodge and following her scientific interests, Genoveva gets to know an impressive array of prominent historical figures: the already mentioned Voltaire, Denis Diderot, Jean D’Alembert, Charles Lemonnier (with whom she works as an assistant for five years), Henri de Boulainvilliers (who makes her horoscope), and Hyacinthe Rigaud (who paints her portrait). Not less important are her encounters with some fictitious characters. For example, a significant influence comes from Tabareau, an engineer with hermeticist predilections who initiates Genoveva into the world of arcane symbols by showing her the carved figures on the tympanum of a small house in Rue aux Fèvres in Lisieux and on the facade of Hotel d’Escoville in Caen. The unsuspecting scientifically-minded Genoveva is overwhelmed by this mystical dimension encrypted into the scenes from New and Old Testament and Greek myths.

Tabareau dragged me again , this time to the Place Saint-Pierre, to the mansion called by the parishioners Hôtel du Grand Cheval erected by Nicolas de Valois, great-grandson of the Flers alchemist, on the facade of which he indicated with the same sibylline gesture an enormous relief of a horse floating in the air, with clouds beneath its front legs, and the name which was given to it was the horse with mane in the wind, on one of its thighs he deciphered the apocalyptic words Rex Regum et Dominus Dominantium, and below was a man carved from stone, with a sword in front of his eyes lacking light, in his right hand he was holding an iron rod, knightly figures that surrounded him were presided over by a solar angel, then he invited me to examine the torus of the portal, under the moulding a little horseman stood victoriously before a confused mass of human corpses and the carcasses of their mounts devoured by birds of prey, the horseman was apparently getting ready to face another horde of knights, and, as Tabareau told me, next to them were depicted the false prophet and the terrible polycephalous dragon which seemingly wished to enter the castle engulfed by flames, and according to the hurried and tangled explanations of my companion, this abundance of symbols was related to the Verbum demissum of Trevisan and to the lost word of medieval architects and masons, as, by the same token, was the dragon on the tympanum situated beneath the peristyle before the staircase of the dome or, on the lateral facade, the beautiful statues of David and Judith, the latter bearing an inscription in French verse, recalling how the daughter of Merari, the Deuterocanonical heroine severs the inebriated head of Holofernes, the Assyrian warrior who besieged Betulia, coupa la teste fumeuse d’Holopherne qui l’heureuse Jerusalem eut defaict, and above these grand statues, the scenes of the rape of Europa and the liberation of Andromeda by Perseus, and also at the top of the skylight turret an allegory of Apollo Pythios, and, in a kind of small temple, the obscene statue of Priapus, the god with the erected phallus, which made all too obvious the heterogeneous spiritual proclivities or at least the excessive symbolism of those who built the house, although Tabareau did not seem to share this view, because, according to his passionate speech, we were clearly dealing with the heritage of the hermetic philosophers of Flers whose arcane symbols and formulas derived from magicians, Brahmans, and Cabalists, for the first time I saw myself surrounded by this world of arbitrary numbers, so distant from the rationalism of François-Marie […]The Weaver of Crowns is a novel in which the mystical and the rational aspects are intertwined, and there is no way Genoveva can escape the realm of the eerie and inexplicable. Among the different genres Espinosa mines for his extensive fresco, the Gothic novel is not the least important. The story of the sickly girl Marie whom the childless Genoveva adopts experiencing an alarming mixture of maternal and sexual feelings towards her, which will be eventually explained, is an exquisite tribute to the traditions of the best of macabre writing. Marie is an autistic sister of one of Genoveva’s lovers, the astronomer apprentice Jean Trencavel. She doesn’t speak a word of French, but communicates instead by uttering fragments of troubadour songs in Occitan. Genoveva takes the seriously ill girl to the thermal baths in Prussia. There she makes acquaintance of erudite aristocrat Baron von Glatz who invites her to stay at his castle, promising to find the best doctor to treat the girl’s disease, which is not named, but is, most probably, tuberculosis. Baron’s castle serves as a setting for educated discussions on a range of topics from the nature of God to the possible existence of vampires. As in any good gothic story, there are dark secrets that Genoveva will eventually discover, and the shocking concluding scene that brought to my mind, when I first read it, the lurid imagery of certain splatter video games.

Despite the countless dangers she is exposed to by her activities, Genoveva lives to be almost ninety, and even at that advanced age she continues to act as an emissary of the Lodge, spreading the ideas of the Enlightenment to the New World. It’s in this capacity that she returns to her native Cartagena where she organises a sort of club of amateur scientists and free thinkers, which she eventually hopes to convert into a fully fledged Masonic organisation. Encouraged by the news of José Celestino Mutis expounding the principles of the Copernican system in front of the viceroy of New Granada, Genoveva decides to write a short astronomical treatise which would elucidate the Newtonian theories of universal gravitation. The octogenarian heroine has a burning desire to connect her homeland to the quickly growing network of universal ideas, but the question remains, is Cartagena ready for this? The Holy Office is still extremely powerful in Spain and its colonies, and, in the evening of her life, like many of her scientific role models before, it is the darkness of obscurantism fervently protected by the Inquisition which she is forced to face and endure to the bitter end. And that is the most tragic, but inevitably logical consequence of Genoveva Alcocer’s enormous thirst for knowledge at the time of great upheavals and expectations she is born into.

This is the longest review I have written so far for my blog, and by now you will have had a pretty clear idea why. The Weaver of Crowns is an unforgettable reading experience that enriches you, makes you look for additional information about the events depicted in it and explore further the topics touched upon within the impetuous torrent of the main character’s captivating narration. It is this time of the year when we see the appearance of the “best of” lists in newspapers, magazines and blogs. There is still time left until the end of 2014, but I am pretty much sure it is unlikely that I will read anything better than Germán Espinosa’s gem of a book this year.

If you can read Spanish, I highly recommend you this informative blog entirely dedicated to Germán Espinosa.

- https://theuntranslated.wordpress.com/2014/11/29/the-weaver-of-crowns-la-tejedora-de-coronas-by-german-espinosa/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.