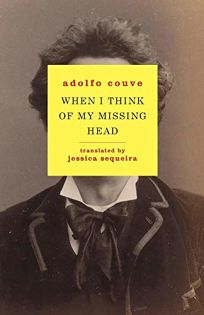

Adolfo Couve, When I Think of My Missing Head, Trans. by Jessica Sequeira, Snuggly Books, 2018.

Camondo, a painter, wakes up one morning in his studio with his head missing, it having been yanked from his body the night before by Marieta, a model. This is a punishment from the gods, who have already taken away his artistic talent. Now, mysteriously resurrected but not quite intact, Camondo wanders about a seaside town wearing a Franciscan habit stolen from church in an attempt to disguise himself.

Published posthumously, When I Think of My Missing Head, by the Chilean painter and novelist Adolfo Couve, here translated for the first time into English by Jessica Sequeira, is a phantasmagorical literary experiment, an existential puzzle with pieces that fit together by secret logic. With tones that are gothic and surrealist, symbolist and magical, this is a highly original work of terror and fantasia.

This posthumous final work by Couve (1940–1998), a Chilean author and painter, is both perfectly readable and totally incomprehensible. Its subtitle is “The Second Comedy,” and it follows La comedia del arte (1995), which shares with this book the principal character of the painter Camondo. Camondo has lost his head—his literal, physical head, which has been turned into wax by the Olympian deities and removed from his shoulders by an angry former model. Few other facts can be ascertained from the narrative, which, while consistently using plain, simple language, jumps from time to time, place to place, and person to person with no obvious pattern. Several conflicting accounts are given of whether and how Camondo gets back his head, and no attempt is ever made to explain how he can live, see, and communicate without its presence. This isn’t magical realism, but an insistent anti-narrative: it takes effort and skill to maintain this sort of clarity at the sentence level without producing some kind of comprehensible overall schema. As a fiercely experimental piece of literature, this will interest fans of Kathy Acker or William S. Burroughs, but conventional enjoyment is almost entirely absent. - Publishers Weekly

The phenomenological condition of headlessness — that is, the absence of a head — has a curiously rich history in Western literature and philosophy. Political theorists from Saint Paul to Thomas Hobbes to Carl Schmitt have taken on the question from a social perspective; interested in the idea of human society as an organic body with a sovereign as head, they have argued that any organization without this head will descend into chaos, and that no matter what claims on behalf of the viability of a headless state might be made by French anarcho-socialists like Fourier, Saint-Simon and Proudhon, and later English corporatists like Barker, Laski, and Cole, society is unworkable should the head be removed. The failures of a ‘headless society’ have been painted in the most vivid of colors.

But what about the individual body without a head? What is the imaginary landscape of the headless person? There is the idea of beheading, the removal of the head as punishment, as exemplified by the guillotine — a clean and clinical manner of separating a body in two resulting in death, a scientifically-designed approach less cruel at least than older methods of terminating a life such as stretching out a body to breaking point with the help of two horses galloping in opposite directions. In addition to the famous decapitations of the French Revolution, from Marie Antoinette to Madame du Barry, there is the beheading of John the Baptist, the result of Herod giving Salome what she desired, immortalized by Gustave Moreau in the intense jeweled tones of his 1876 painting ‘Salome and the Apparition of the Baptist’s Head’; in this image the head retains a sort of life, staring with sorrow and accusation at the woman who ordered it to be severed from the body.

The head has traditionally been thought to contain the mind, the consciousness, such that its removal suggests removal of thought, logical cognition and organized deliberation. Descriptions from the ‘outside’, however, decadent as they may be, do not represent the lived experience of being without a head. Where are the descriptions of headlessness from within, from the perspective of someone missing this part of the body? There is, of course, a paradox in this — how can one think and describe if one is headless? — but where some see impossibility, others see opportunity.With his final book, the Chilean writer Adolfo Couve takes on precisely this philosophical question. His work incorporates and personalizes the concerns voiced by centuries of Western tradition, centered around the importance of the head which contains the brain as center of consciousness. When I Think of My Missing Head, Couve’s final novel, reflects the questions that preoccupied him at the end of his life. It contains a contradiction from its very title, of course — what does it mean to think without a head? — but from this paradox emerges the fragmentary, oneiric abundance of Couve’s vision, which inquires into what it means to exist as a headless person without coherent rational thought.

A reader who plunges into this book without warning will find herself adrift in a chimerical world without obvious grips. Since Couve narrates in a non-linear style, representing a jumpy and fractured form of thinking, this short novel requires more attention than a traditional book of its size might. Couve is often described by Chilean critics as a writer with a classical style; he himself proclaimed allegiance to a realist French tradition that includes Balzac, Stendhal, Flaubert, Maupassant, Merimée, Michelet and Rénan. That might be somewhat true in his earlier books, even if a UK or US reader still finds these quite ‘experimental’ compared with typical novels from their countries; in When I Think of My Missing Head, however, the structure is anything but straightforward. Some critics have suggested reading this novella as a sort of puzzle book, in which the reader can fit the various fragments together. The metaphor is useful, but only partially — if this is a puzzle, there are gaps and overlaps by the pieces, and such rational logic does not fit the more poetic atmosphere of the book.

All this said, When I Think of My Missing Head is quite clear at the levels of sentence and paragraph. Couve operates in terms of clear anecdotes. It is only when the reader stops and asks how a page connects to the material from a few pages before that the head-scratching begins, as it were. Anecdote follows anecdote but what joins the parts is more theme than plot — the constant of headlessness. An ironic and playful tone throughout lightens up the somewhat grim material; the first and third sections are also recounted in first person, which gives a picaresque quality to the different adventures as they move through spiritual, oneiric and realistic realms.

Taking a step back, the book does have a structure that can be summarized as well. Three parts comprise it: ‘Cuando pienso en mi falta de cabeza’ [When I Think of My Missing Head], ‘Cuarteto menor’ [Minor Quartet] and ‘Por el camino de Santiago’ [The Road to Santiago]. In the first part, the ‘narrator’ is the painter Camondo, a double for Couve himself. Camondo wakes up in his studio literally missing a head, since the night before his model Marieta has yanked it from his body. This is understood to be yet another punishment from the gods, who have taken away his artistic talent. Now, mysteriously resurrected but not quite intact, Camondo wanders about his seaside town, reacting to the discovery of his condition, seeking some kind of normality by wrapping himself in a cloak stolen from church to create the illusion of a head and railing against the gods who have permitted this to happen.

As an outsider, Camondo now experiences life in town with a sense of disoriented strangeness. This leads him to memories of travel with his grandmother. He remembers seeing a disconcertingly headless statue in Florence, which makes him say that: ‘What my grandmother did not know is that I found myself in Florence the night of 17 November 1494’. Here he describes a carnivalesque scene — pure imagination, a dream, or what?— which in turn segues into recollections of bohemian life in Santiago when he and his friends would hold parties involving desecrations of the church. Here, perhaps, lies one explanation for the gods’ wrath.

Couve thinks in similes not metaphors; memories, visions and bohemian reenactments are to him not performances of reality but reality itself. The cloudy jumps from one scene to another in decadent descriptive language are exhilarating, and it is never entirely clear what is really happening and what is fantasy.Did Camondo really die? Was his ‘wax head’ really plucked off his body? Or does he simply feel this way? Perhaps it is the reasoning mind that separates ‘reality’ from other states, while in the headless mode existence and fantasy co-exist in a cauldron of potentiality. The idea of ‘losing one’s head’ is both metaphorical and literal; just as in Catholic transubstantiation an abstraction becomes reality, the host becoming the flesh of Jesus, here the abstract loss of rationality of ‘losing one’s head’ is represented as a physical loss, a powerful image — one remembers that Couve is a painter. All this is mirrored on a formal level in the book as the plot itself ‘goes to pieces’.

In ‘Minor Quartet’, the second section, we move away from Camondo to a series of other characters. The ‘quartet’ consists of four stories with two parts each, for a total of eight fragments. ‘Bad Head’ tells the story of the madness of model Marieta, ‘Losing one’s head’ the adultery of the clown Tony Bombillín, ‘Head of a girl’ the anguish of an old woman who lives off the memories of her painter father, and ‘Breaking one’s head’ the preparations of a cook to garnish a pig discovered in a waterwheel. These fragments link to one another as well as to the Camondo sections, in more or less obvious ways; each anecdote also possesses such a wealth of detail that it can be read as a story in its own right.

In the third section, ‘The Road to Santiago’, we return to Camondo, on his way to Cuncumén before he goes back to Santiago. The tone in these sections is more allegorical. Camondo meets a collector of antiques and curiosities who has discovered his wax head; inexplicably the dealer turns into a sort of devil who pursues him with empty eye sockets, a putrid green mouth and ugly hands facing backward; at last Camondo ends up in a church where he discovers his head displayed as the head of Saint Tarcisius. From here we move into a section from the perspective of the mentor of Tarcisius, portrayed as a coward who watches as the saint is martyred by circus folk but does nothing. (The circus, here as elsewhere, is seen to be not a docile place of fun and games, but rather a locus of desire and danger.)

The following section is a dream in which Camondo meets a beautiful young woman who desperately wants him to paint her portrait, removing her clothes and begging him again and again, which Camondo refuses out of a pact not to paint anymore. The last section finds him at the house of the young woman’s father, a millionaire in town; Camondo stealthily breaks into a party but is found out and humiliated. The book ends with a deus ex machina, a benevolent divine presence this time, in the form of the Consul General of Chile in New York. This diplomat knew Camondo when he was a great artist and defends him before all; he then has his chauffeur drive him back to Santiago in a limousine, and the book ends in a peaceful drift into sleep. In these final sections, the loss of a head prompts examinations of horror, longing, humiliation, displacement and relief, which reach an existential intensity that one can only speculate were felt by Couve himself.

When I Think of My Missing Head is a macabre work with dusky tones—Couve killed himself in 1998 in his house in Cartagena facing the sea—but it is also a work full of parody, above all about a career in painting. While the book is a stand-alone work, it can also be read productively in relationship with Couve’s earlier novel The Comedy of Art, which not only features Couve’s doppelgänger Camondo as narrator and the same secondary characters that appear in the ‘Minor quartet’ section of When I Think of My Missing Head, but takes on a similar plot of vengeful gods in a small seaside town. This in itself has a tragicomic effect—the great themes of religion, philosophy and art are all put to service in the life of a tired painter in a tired town.

As Ignacio Valente points out, The Comedy of Art marked a turning point in Couve’s work from realism toward ‘a freer and looser way of narrating that gives way to the grotesque, the phantasmagorical, the mortuary and almost postmortuary, the spectral on the very edges of hell… without losing those plausible and almost picaresque dimensions’. The loose style continues in When I Think of My Missing Head, which possesses a ‘poetic prose’ that for Rosa María Verdejo expresses a ‘troubling and painful search, saturated by the will to preserve certain life experiences through symbols and the imagination, as a game in which past and present combine in multiple spaces’. José Alberto de la Fuente makes the point more bluntly, writing that the ‘lack of a head’ is ‘a way to conjure up madness and death, to displace desperation and suicide into another temporality’.

Regardless of the effects of Couve’s own mood on this work, it is possible and illuminating to read the novella on terms beyond the author’s life. Other critics have commented on the work’s treatment of the grotesque; Adriana Valdés, who wrote the prologue to the first edition, notes that in When I Think of My Missing Head the grotesque appears to be engaged in a duel with the sublime. Felipe Toro notes that the fragments read like naturalezas muertas, ‘objects in repose (small everyday treasures) exposed to the gaze of the reader’. He also makes the connection between Camondo’s wax head yanked from him without pain and the ‘enchanted head’ presented to Don Quixote in Cervantes’ famous work.

Couve’s influences, as well as those he has influenced, are another area of interest. Leonidas Morales has associated Couve with the Chilean writer José Donoso, who works with similar thematics of closed spaces, big houses, elderly characters and decaying landscapes which serve as allegory. The relationship between Couve’s artistic work and his literature is also a fertile field. In 2002, Couve’s student Claudia Campaña, now a successful professor of art history, assembled a catalogue of his paintings with adjacent commentary, presented at the Santiago Museum of Fine Arts; this included several pieces by the author that had not previously appeared. Campaña has since written other texts on the author’s paintings connecting them to his novels.

When I Think of My Missing Head is a complex headless footnote, a fascinating coda to Couve’s life. It is capable of containing numerous readings from the personal to the mythological. As a translator, I have attempted to capture its quality of precision and multiplicity, in which no sentence reigns sovereign, but every sentence is a daub of paint that further enriches and illuminates a work, a life and a tradition. - Jessica Sequeira

https://minorliteratures.com/2018/03/21/on-headlessness/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.