Walter D. Redfern, All Puns Intended: The Verbal Creation of Jean-Pierre Brisset. Routledge, 2001

"The 19th century in France spawned numerous 'fous litteraires, one of them being Jean-Pierre Brisset (1837-1919). An individualist among individualists, he dismantled the existing French tongue, reshaping it to suit his own grandiose purposes, which were to explain afresh the development of human beings (from frogs) and of their language (from croaks). Continuous and ubiquitous punning was a unique feature of his writing. In this study, Redfern examines such themes as the nature of literary madness, the phenomenon of deadpan humour, the role of analogy, and the place of institutional religion in Brisset's creative rewriting of the creation."

Brisset had been a good soldier, and he was a model railwayman: there was no hint during the working day of the oddity of what he was up to after hours... The fact that frogs turned out to speak what was easily recognizable as French seems at no point to have fazed Brisset, and since the original human language has willy-nilly to be universal, all other known languages must be capable of being derived from French, which was pleasing news for a Frenchman. (John Sturrock Times Literary Supplement, 18 January, 2002, 41)

What indeed can one make of this autodidact who mused about etymology without mastering Latin and about human origins without reading Darwin? Brisset can readily be dismissed as arrogant, Gallocentric, sex-obsessed or simply unreadable. Yet Redfern finds in his work a splendid proof of the instability of language, and also a fine pretext for learned digressions about puns and myths and free associations and what Ponge called ‘amphibiguité’... The main pleasure given by this book actually comes from Redfern’s own style, which is intelligent, energetic, quirky and never too self-indulgent. (Peter Low New Zealand Journal of French Studies, 24/2, 2003, 51-2)

Redfern’s treatment is interesting and wide-ranging, but interesting because it is wide-ranging. (Stephen F. Noreiko French Studies, LVII.2, 2003, 255-6)

‘Brisset had been a good soldier, and he was a model railwayman: there was no hint during the working day of the oddity of what he was up to after hours... The fact that frogs turned out to speak what was easily recognizable as French seems at no point to have fazed Brisset, and since the original human language has willy-nilly to be universal, all other known languages must be capable of being derived from French, which was pleasing news for a Frenchman.’ — John Sturrock

‘What indeed can one make of this autodidact who mused about etymology without mastering Latin and about human origins without reading Darwin? Brisset can readily be dismissed as arrogant, Gallocentric, sex-obsessed or simply unreadable. Yet Redfern finds in his work a splendid proof of the instability of language, and also a fine pretext for learned digressions about puns and myths and free associations and what Ponge called 'amphibiguité'... The main pleasure given by this book actually comes from Redfern's own style, which is intelligent, energetic, quirky and never too self-indulgent.’ — Peter Low

‘Walter Redfern ... a particulièrement raison de s'appuyer sur les travaux les plus sérieux de ces dernières années pour situer enfin la place de Brisset et l'impact de ses ouvrages parmi les créateurs littéraires de la fin du XIXe et de la première moitié du XXe siècle. ... Un bonne bibliographie sert d'appui à cette monographie intelligemment projetée.’ — Jacques-Philippe Saint-Gérand

‘Redfern's treatment is interesting and wide-ranging, but interesting because it is wide-ranging. He shows that Brisset has interested a lot of interesting people, then sums him up: 'Brisset is a trampoline: to take off from and to come back to.' I think he is half right: one may be glad that he existed to provoke this book.’ — Stephen F. Noreiko

Jean-Pierre Brisset as an antidote to the anthropocentric structuralisms of Saussure, Lacan, and Chomsky. Brisset maintains that human beings are immediately descended from frogs. He supports his claim with exhaustive linguistic analyses. Our speech, he shows, is a hypostasis of frogs' croaking in the mudflats; our writing conserves the traces of their obscure hatreds, jealousies, and battles. Brisset, much like McLuhan, affirms the tactility of language, its oral and aural density, its rich, viscous materiality. He "puts words back in the mouth and around the sexual organs." Language arises out of orgasmic screams and bodily spasms. There's no clear dividing line between body and thought, or nature and culture, just as there is none between the water and the land. Language and sexuality are not the clean, abstract structures the so-called "human sciences" have long imagined them to be. Rather, they are forces in continual agitation in the depths of our bodies. --DOOM PATROLS, Chapter 4, Michel Foucault, Steven Shaviro [1995-1997] via http://www.dhalgren.com/Doom/ch04.html

Born into a farming family of La Sauvagère, Brisset was an autodidact. Having left school at age twelve to help on the family farm, he apprenticed as a pastry chef in Paris three years later. In 1855, he enlisted in the army for seven years and fought in the Crimean War. In 1859, during the war in Italy against the Austrians. After he was wounded at the Battle of Magenta, he was taken prisoner. During the Franco-Prussian War, he was a second lieutenant in the 50e régiment d'infanterie de ligne. Taken prisoner again, he was sent to Magdeburg in Saxony where he learned German.

In 1871, he published La natation ou l’art de nager appris seul en moins d’une heure (Learning the art of swimming alone in less than an hour), then resigned from the Army and moved to Marseilles. Here he filed a patent for the "airlift swimming trunks and belt with a double compensatory reservoir". This commercial endeavor was a complete failure. He returned to Magdeburg, where he earned his living as a language teacher, developing a method for learning French, which he self-published in 1874.

Brisset became stationmaster at the railway station of Angers, and later of L'Aigle. After publishing another book on the French language, he undertook his major philosophical work, in which contended that humans were descended from frogs. Brisset supported his contention by comparing the French and frog languages (such as "logement" = dwelling, comes from "l'eau" = water). He was serious about his "morosophy", and authored a number of books and pamphlets put forth his indisputable substantiations, which he had printed and distributed at his own expense.

In 1912, novelist Jules Romains, who had obtained copies of God's Mystery and The Human Origins, set up, with the help of fellow hoaxers, a rigged election for a "Prince of Thinkers". Unsurprisingly, Brisset got elected. The Election Committee then called Brisset to Paris in 1913, where he was received and acclaimed with great pomp. He partook in several ceremonies and a banquet and uttered emotional words of thanks for this unexpected late recognition of his work. Newspapers exposed the hoax the next day.

In 1919, Brisset died, aged 81, at La Ferté-Macé.

Posthumous reputation

The Complete Works of Brisset were reprinted by Marc Décimo, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2001. In an essay entitled, Jean-Pierre Brisset, Prince des Penseurs, inventeur, grammairien et prophète, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2001, Marc Décimo has given a biography, explanations about Brisset's delirium about frogs as ancestors of humankind. Translations in several languages (European languages, Wolof, Armenian, Arabic, Houma, etc.) can be found in this book as well.[citation needed] It also includes the major texts written about Brisset by Jules Romains, Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, Raymond Queneau, Michel Foucault. In 2004 the Art of Swimming (as a frog) was published in paperback.

Around 2001, Ernestine Chassebœuf wrote several letters to French politicians, universities, railway stations, library directors, psychiatric hospitals, to suggest they name a street, a university, etc. after Brisset. Their answers were published on a website dedicated to him,[1] but there is no "rue Jean-Pierre Brisset" yet. Thanks to a bequest to Jules Romain, an annual dinner in his memory was made possible until 1939.

Brisset is listed as a saint on the 'Pataphysics calendar. His writings were in print as of 2004. -Wikipedia

when they elected old Brisset Prince des Penseurs, Romains, Vildrac and Chennevière and the rest of them before the world was given over to wars Quand vous serez bien vieille remember that I have remembered, mia pargoletta, and pass on the tradition—Ezra Pound, “Canto LXXX”

In January 1913, French papers announced that a little-known seventy-six-year-old philologist and philosopher named Jean-Pierre Brisset had been voted the “Prince of Thinkers” in an election organized by the recently founded Society for Ideology. He had solidly beaten out the better-known, second-place candidate, Henri Bergson. A ceremony was arranged for April of that year. Coming into Paris, the great man was met with a solemn reception at the Montparnasse train station, where a young girl presented him with flowers on the platform and the assembled crowd was treated to a poem that Charles Vildrac had written especially for the occasion. After an intimate lunch, Brisset was brought to the Pantheon to offer a few choice words by the foot of Rodin’s Thinker.

He subsequently met with members of the press, including reporters from Le Figaro, Le Matin, and Excelsior, and then headed to the Hôtel des Sociétés Savantes to deliver a public lecture in which he explained that Man had descended not from apes but from frogs, and that proof of this could be discovered by a close examination of ordinary language, in which the history of our species, along with the mysteries of God and of the world, remained encoded.1 Human speech is the book bound with seven seals described in Revelation, and Brisset himself was the seventh angel who had broken the final seal and revealed its contents. The words we use today still register our initial reactions to moments of great import in the course of our divinely orchestrated evolution—the moment when humans’ amphibious and asexual ancestors discovered their incipient genitalia; early acts of violence destroying the peace that once existed between animal and man; the experience of good and evil and encounters with angels and demons (who were also our ancestors, a middle stage of development between Man and frogs).

Though Brisset’s books had revealed the secrets of God and Man deduced through his analysis of the French language, he had emphasized in his La science de Dieu ou la creation de l’homme (The science of God or the creation of man) of 1900 that God’s language is equally audible in all current languages and he was not claiming any special status for his own national tongue: “The present work cannot be translated in its entirety, but each language can be analyzed by following the Great Law and the methods presented in this volume. The result will be the same: The creation of man, both as animal and as spirit.” - Kevin McCann

https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/50/mccann.php

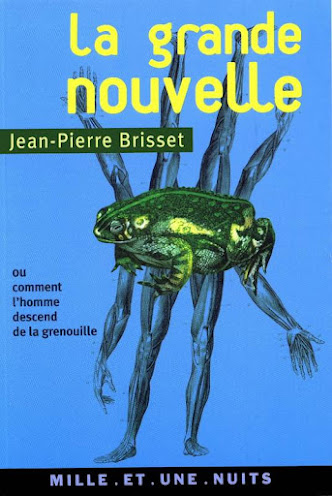

The big news: or how man descended from the

frog

After having been a pastry chef, a soldier then a professor of modern languages, Jean-Pierre Brisset (1837-1919) belongs to a line of enlightened poets, creative and eccentric theoreticians who never lose their seriousness. In 1900, he intended to reveal the origins of the human species and of language in a new Gospel which he printed in a thousand copies and distributed free of charge: The Great News. He reveals the Great Law hidden in speech and, through the play of homophony, forges a surprising conception of human evolution: man is descended from the frog. His enterprise did not fail to be praised by the surrealists and by Jules Romains, Max Jacob and Stefan Zweig who awarded this “literary madman” the title of “Prince of thinkers”. [by Google translate]

The Science of God: Or the Creation of Man

Is there an intelligent, living power, having its own, invariable will, real and constant authority and power over individuals, families and peoples? —We can boldly assert that there is no question more important, nor one which deserves to the same degree to occupy the mind of the intelligent man.

Now, to this question we can answer with absolute conviction and certainty: Yes, this power exists; yes, there is a God or a creative spirit, elevated above all human intelligences and whose power extends to all the stars and to everything that lives with its own or general life.

The result of a selection made from the funds of the National Library of France, Collection XIX aims to introduce classic and less classic texts in the best editions of the 19th century. [by Google translate]

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.