Mochu, Bezoar Delinqxenz. Ed. by Edit Molnár

and Marcel Schwierin. Sternberg Press, 2023

Taking off along the grotesque evolutionary curve of the internet, this novel by Mochu brings together Japanese otaku subcultures, Hindu mythology, darknet highways, ultraviolent cyberpunk forums, and renegade university departments to forge a transnational narrative that trips through the incompatible fantasies of rationality and civilization, with wormholes through ancient tales, recent cinema, plain-wrong art histories, and pirated philosophical reflections.

The novel opens with a case of abduction in India. The operations of a far-right publishing house are interrupted by extraterrestrial influences with political intent. The attack on a science-fiction writer at a beach in Goa seems connected to a bot-propelled puzzle revolving around the defacement of Medieval temple relics elsewhere. A detective specialized in interstellar sociology finds clues that point to a transgalactic anarchist group with ties to online Posadist forums, while Eurasian political theory circulates as noise-objects in Goa’s beachside clubs. Meanwhile, occultist explorers in the sci-fi writer’s story find that the legendary homeland for Hinduism in the Arctic has become infested by “Gradients of Hegelian Unhappiness” by way of an invasive subzero entity buried in deep snow. The detective’s investigations eventually turn metaphysical, settling on impossible solutions spanning the far reaches of outer space.

Reactionary behavior on the internet, having spawned numerous retroactive origin stories for itself, takes on a tentacular presence across diverse political spectrums, time periods, and cultural contexts, giving the impression of a vast and tangled entity with distributed intelligence. Fatally fused by a common hatred for the legacies of the Enlightenment, popular manifestations go by terms like “alt-right” and “neo-reaction,” powered by nerdy forums and blog posts across the web. Stationing conspiracy theory itself as the central form of thinking, acting, and concept-making in the twenty-first century, Bezoar Delinqxenz is a mixtape simulation of these entanglements at the borderlands of fiction, insanity, and political emancipation.

Mochu, Nervous Fossils: Syndromes of the

Synthetic Nether. Reliable Copy and Kiran

Nadar Museum of Art. 2022.

Stationed around an art freeport megaproject in the Persian Gulf, and hopping across numerous locations real and fabricated, the book spins off into shadow- histories of synthetic colour production, abstruse citizenship schemes, nuclear warning signs, and syndromes leaking back from the future. During their idiosyncratic philosophical debates, the project employees gradually begin to sense a manic sensorium operating beneath their seemingly sterile financial and logistical systems. Troubles erupt while discussing works of art; futurist imaginaries of financialisation stumble upon the deep inertia of historical time preserved in museums and tombs. Monumental works of art pleasantly rotting in history enter into messy partnerships with volcanoes, hadopelagic planktons, and whimsical vibes of rich people. Stakes are endless while smiles are fake, as the debates swerve into the discreet horror of corporate gleefulness.

For Sophie J Williamson, works by Mochu, Semiconductor, Larissa Araz, Alper Aydın, Ithell Colquhoun and others search for different ways to engage not only with the ‘critical zone’ of Earth’s surface but also the planet’s volatile core, enabling us to reconnect with our ‘geological ancestry’.

In author NK Jemisin’s dystopian trilogy ‘Broken Earth’, 2015–17, precarious societies struggle to survive amid regular apocalyptic cycles and periodic extinctions. Having previously plundered the earth’s resources – angering Father Earth, the sentient inner being of the planet – and provoked its now constantly agitated seismic activity, the ruling elites exploit a minority race, the Orogenes, which, as the name implies, possess orogenic powers: their senses can probe down into the earth’s crust, diverting kinetic or thermal energies to calm and quell shakes, softening the collisions of tectonic plates. A thinly veiled analogy of embedded colonial oppression – the Orogenes are both feared and ruthlessly exploited – the narrative must also be read as a response to the reluctance of society to attune itself to earthly languages; wanting to extract, destroy and control, rather than seek symbiosis with the inorganic. Against the background of the Randian repercussions of the current pandemic, and the fragility of ecological hope in the face of the changing winds of party politics in the most powerful nations, ‘Broken Earth’s analysis of humanity’s cut-throat survival tactics slices closer to the bone than most.

Learning new ways to inhabit the Earth is our biggest challenge; Bruno Latour argues that ‘bringing us down to earth’ is the new political task. But how do we do this when the earth below our feet seems so unknown, impenetrable beyond the barrier of urban concrete and previously assumed rules of engagement with the planet? In Timothy Morton’s podcast series The End of the World Has Already Happened, he admits that the overwhelming reports that we hear of climate change are enough to cause us to curl up into the foetal position and cry: a reaction, he says, that is perfectly reasonable. In A Billion Black Anthropocene or None, 2018, Kathryn Yusoff debunks geological conceptions that have rendered human society and inorganic matter a simple binary: geology is often assumed to be ‘without subject (thing-like and inert), whereas biology is secured in the recognition of the organism (body-like and sentient)’. Instead, she argues that geology inherently carries with it the violence of colonialism and capitalism, and while the exact moment of the Golden Spike marking the beginning of the Anthropocene is debated, she writes that it is ‘an inhuman instantiation that touches and ablates human and non-human flesh [...] It rides through the bodies of 1,000 million cells: it bleeds through the open exposure of toxicity, suturing deadening accumulations through many a genealogy and geology.’ How do we transcend what she refers to as this ‘shock and guilt’ in order to act? How dowe relate the corporeal life of the planet to our own, without losing sight of agency, of the personal, so as to rebuild a stabilising kinship with the geological?

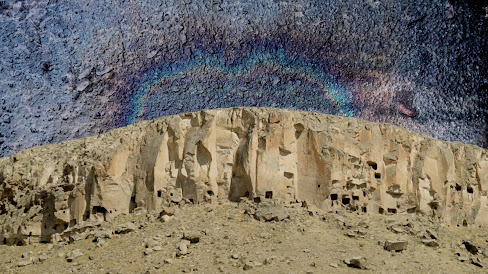

From the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh to Arsan Duolai, Hades or Abrahamic hell, the cavernous depths below the earth’s surface have been feared throughout human history. And while modern science has looked out to the cosmos to learn about who we are, the world below our feet remains a dark matter closer to home: unknown, unseen and ominously quiet. David Attenborough’s honeyed voice-over, in A Perfect Planet, tells of us of life’s genesis erupting from the earth’s core: ‘Volcanoes are certainly destructive, but without these powerful underground forces there would be no breathable atmosphere, no oceans, no land, no life.’ This seismic ‘underland’ is our life support system, yet it is nevertheless mistrusted. Contemporising the ubiquitous underworlds of folklore and religious fables, Mochu’s performance-lecture Toy Volcano, 2019, uncovers the dread of the unknown darkness below embedded in the popular subconscious. He narrates a story of legendary rock formations, sealed off from visitors by earthquakes in an unnamed valley. Immortalised in fan-fiction manga animations and B-movie horror films, the tales try to make sense of mad geologies and ‘portable holes’, calling on geotrauma therapists, archaeologists, miners and volcanologists to unravel the manifold interpretations of a snapshot of the earth’s evolution. Toy Volcano reveals speculative horrors and our fraught relationship with geology via suspect materials, the fantastical physics of manga animations and trypophobia: the fear of holes. While staying in Cappadocia, in Central Anatolia, the film location for Mochu’s unnamed valley, I found myself nervously venturing into deep mountainside crevasses. I was reminded of Robert Macfarlane who, in Underland, describes how his heart hammers a warning in his ears, the ‘weight of rock and time bearing down’ on him: rock formations and ruckles might hold their position for tens of thousands of years, but an earth tremor might reorder these structures in an instant. These deep-time openings become the protagonists of Mochu’s fictional world: the mountain is a cocoon housing a writhing mass of volcanic worms and the unruly holes take on a predatory, parasitic body-snatching life-form, attracting human prey into their depths.

Mochu’s performance was commissioned as part of Ashkal Alwan’s ‘Home Works 8’ forum before what became known as Lebanon’s October Revolution erupted, filling the streets with fire blockades, protesters and water cannons. The long-anticipated uprising found its tipping point in tax hikes, while at the same time uncontrollable wildfires ravaged the countryside and ‘shadow economies’ suffocated coastlines with dumped waste, visible scars of the impact of capitalist greed and corrupted human interests. Yusoff argues that geology is neither politically nor socially neutral, that such colossal shifts like these are caused by capitalism and colonialism which directly impact our ecosystems, subsequently leaving a geological mark on the ‘Critical Zone’ of the surface of the planet. I finally saw the performance a year later, this time amid the global sense of existential uncertainty that has defined the Covid-19 pandemic. As Mochu’s manga official, battling the geological parasite, disintegrates into his new, holey existence, he observes: ‘My skin is a green screen, an invitation for contaminations. Now the ethereal has to be turned material [...] The worms have begun their work.’ Humanity’s ravenous poisoning and plundering of the land is reversed. Two-thousand miles away, meanwhile, anthropocentric global warming melts the permafrost across the Siberian tundra with terrifying speed; the billions of tons of carbon suspended in its frozen organic matter will be released into the atmosphere, rapidly suffocating existence as we know it. Earth is turning our weapons of destruction against us.

Closer to home, Semiconductor’s All The Time In The World, 2005, animates Northumbria’s landscape to the rhythms of the geological activity below the surface. Quintessential British hillscapes are thrown into disturbing disruption as the data of seismic activity, which has shaped and formed the land over millions of years, is played out at the speed of sound; frenetic vibrations quake and shake the landscape like an elastic drumhead. When it finally halts, the disruption remains uneasy and the image of tranquil rolling hills is exposed as only a fleeting – and precarious – geological moment. Tectonic movement continues out of sight, below, slowly building tension. How do we, like Jemison’s Orogenes, attune ourselves to these rhythms to find a harmonious balance? As Anna Tsing et al write in their Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, the next great extinction comes not from an asteroid from outer space or the geological beyond our control, but from industrial overproduction; the ‘Great Acceleration’ of the Anthropocene is the result of numerous ‘small and situated rhythms’, deadly in their accumulation. A recent article in Nature, for example, carrying the self-explanatory title ‘Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass’, pointed out that global manufacturing produces mass equal to every living person’s body weight every single week and, what’s more, the weight of the world’s plastic alone is now double that of all animal life on earth. For generations, ecology activists have pleaded for us to slow our consumption of the planet’s resources, without success. In his 2018 book Down to Earth, Latour argues that the perspective of the global – the view solidified in popular consciousness of the planet as a falling body amongst others in the infinite universe of Galilean objects – grasps all things ‘from far away, as if they were external to the social world and completely indifferent to human concerns’. Humanity has seen the planetary from the viewpoint of space, a globe to be capitalised in a universe waiting to be conquered. Latour argues that this has caused us to become detached from the vital planetary relationships that make life on Earth viable. ‘Little by little,’ he suggests, ‘it has become more cumbersome to gain objective knowledge about a whole range of transformations: genesis, birth, growth, life, death, decay, metamorphoses.’ Since mobilisation is not possible as long as nature is conceived of in the abstract, we need to resituate our concept of ‘homeland’, linking ourselves not to false notions of nation states, but to a soil – a Heimat, as Latour writes – with all the dangers that link soil and people.

While staying in Turkey, I felt the strength of this affinity among the people I met. As with so many countries in the Middle East, wars and pogroms have uprooted populations in Turkey time and again, creating strong bonds to the soil from which they were borne or from which they are denied. A profound closeness to the land is palpable, for example, in Fatmas Bucak’s studies of borderland materialities, Kerem Ozan Bayraktar’s micro and macro journeys and transformations of dust, Canan Tolon’s fragmentary landscapes, the absences and destructions in Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’s installations, or Larissa Araz’s fig tree growing from the seeds in the stomach of a corpse in an unmarked cave grave. In Cappadocia, geological form is palpably intertwined with the daily activities of its inhabitants, both human and non-human. Created out of the ash from two supervolcanos ten million years ago, the soft tuff rock has eroded into cavernous valleys and – easily carved by hand – was populated by cave dwellers. Entire populations would retreat underground, living a secret life below the surface in the vast networks of tunnels and caverns: refuges from wars, colonisers and persecution. Alper Aydın lives on the shore of the Black Sea, where his work – and his daily life – unfold within the rhythm of the land where he was born. Commissioned to make a new work in the Cappadocian valleys for Cappadox 2017, Aydın’s performance Shelter saw the artist meld himself into this unfamiliar land in order to speak to it. Almost naked and using only his hands, he sculpted a dome around himself with mud hollowed out from below his feet until he was completely encased in his earthy subterranean sanctuary. ‘Can we perceive cosmos through looking at the depths of the earth, the world under our feet?’ he asks. Aydın’s earthy hideaway echoes 17th-century Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher’s concept of the ‘geocosm’, a geological womb, as described in his lavishly illustrated Mundus Subterraneus. Kircher saw the ‘underworld’ as a macro-cosmic architecture that parallels the microcosm of the human body, a geological cosmos entangling telluric, organic and human worlds: ‘a harmonically structured organ, dark and full of wondrous creatures, animated by heat diffusing throughout it, connecting the terrestrial with the divine’. Aydın builds a cocoon around himself to nurture the symbiotic and, through the seeming simplicity of his action, to interact with the land through its natural properties, growing into it, to emerge once again. Like the mathematician’s insistence that a mug and a doughnut are topologically identical, Aydın moulds the land anew, transforming it out of itself, taking and adding nothing, enabling a dialogue whilst also letting it slope back afterwards to its topological beginnings. Attending to what Latour refers to as earth’s internal ‘collectivities’ – the collective interactions between all matter – with sensitivity to human actions is, he argues, vital in order to grasp the earth’s rhythms from ‘up close’ and to become truly ‘Terrestrial’. His argument builds on those of theorists such as Donna Harraway and Tsing, whose writings over recent years have disassembled the image of the wholly singular Earth. Physicist and philosopher Karen Barad invokes quantum field theory to reveal Earth’s haunted landscapes as strange topologies: ‘Every bit of spacetimemattering is ... entangled inside all others.’ With this resituated way of seeing the planetary, Latour proposes that the new distribution of these metaphors and sensitivities are essential to the recovery of the planet and the reorientation of political affects.

In Ithell Colquhoun’s enchanting prose on life in rural Cornwall, The Living Stones, she writes, ‘The life of a region depends ultimately on its geologic substratum’; characterising the land, it sets up a chain reaction for everything else that lives there. The inherent connection between mineral and organic bodily forms was an enduring preoccupation for her. Seeking the pliability of the in-between, a slippery space between two worlds unnecessarily delineated from one another, for Colquhoun volcanoes, caves, rock pools and natural springs are permeable points in the ever-transient membrane between natural, human and spirit worlds. In Scylla, 1938, one of Colquhoun’s most loved double-image paintings, one’s eye drifts from seeing a pair of legs in bathwater to two craggy pillars harbouring a sea cove, a clump of seaweed or a flare of orange pubic hair lying conspicuously between the two. Her images of these liminal zones oscillate between the languages of flesh and minerality, a momentary blurring between the organic and non-organic, the living and the dead – a gateway between worlds. In lesser-known works on paper, Colquhoun finds meaning in the natural behaviours of her materials: landscapes out of the smoke marks or geological formations traced among the impurities of a blank sheet of paper.

These transformations reveal her dedication to tuning into the pre-existing language of the planet’s matter, whether it is graphite dust over a page or stalagmites across a speleothem. Roger Caillois would argue that, ‘being himself lacking in density, the last comma into the world’, it is merely the human condition to see our likeness in nature. In his stunning illustrated narrative on the subject, The Writing of Stones, he gruesomely interprets, in jaspers and agates for example, ‘an empty socket with a freshly removed orb dangling like wet rag [...] gnarled and ringed phalluses, swollen and purple, without their foreskins, the glans all wrinkled [...] rumbling innards, excited vulvas, striated tendons; pale partial globes jointed like the knees and elbows and hips of celluloid dolls’. He writes that there is no ‘site in nature, history, fable, or dream whose image the predisposed eye cannot read in the markings, patterns, outlines found in stones’. Colquhoun’s eye isn’t one of apophenia, though; it is not a correlation she depicts but a true sameness.

Her works are perhaps more akin to the mythological petrification of Medusa and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, or the Cornish folklores of Colquhoun’s nearby Merry Maidens stone circle and the Nine Maidens of Boskednan monoliths. Yet her works don’t seek alchemical transformation but instead present a worldview that they are equally live. In paintings such as Alcove I, 1946, and Stalactite, 1962, she travels into the geological underworld while simultaneously delving through stratum of subcutaneous layers to reach internal organs, as if both are made of the same materials but of different longevity: one fleshy, the other leaden. Rocks are bodies, bodies are rocks. For Colquhoun, to venture into the darkness of Vow Cave was for her to climb into the womb of her local landscape: finding a personal heritage, stretching back some 4.5 billion years, throughout all its organic, sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous transformations. As her paintings gaze out to the world from their cavernous underlands, the human and the geological amalgamate to become one: the body of the earth.

Colquhoun writes, ‘the structure of its rocks gives rise to the psychic life of the land code on granite, serpentine, slate, sandstone, limestone, chalk, and the rest [...] each being coexistent with a special phase of the earth-spirit’s manifestation’. The sense of conscious thought entangling with mineral existence is often echoed by those seeking an affinity with the land. Ursula K Le Guin’s admission, for example, that she is ‘just mud’, impressionable and yielding, in her text ‘Being Taken for Granite’, evokes the emotional affinities to mineral existences and their personalities. ‘One’s mind and the earth are in a constant state of erosion,’ Robert Smithson wrote, ‘mental rivers wear away abstract banks, brain waves undermine cliffs of thought, ideas decompose into stones of unknowing [...] The entire body is pulled into the sea cerebral sediment.’ Even after determinedly crediting his mineral readings to the ‘willing eye’, Caillois can’t help but speculate that this inextricable complexity of interactions over millennia could perhaps be owed to a larger cosmic consciousness, and that it is natural for humanity as its heir to recognise ‘through their very failure, a glorious way ahead’.

If, as these artists and writers tentatively propose, we as a species are able to find a bodily and cerebral entanglement with our geological ancestry, what then of the future? ‘Her tongue is as long as time. Not death can languish, no quake can slide her,’ narrates the disembodied, ethereal voice of Ben Rivers’s 2019 film, Look Then Below. Deep below the earth’s surface, hidden in a network of glowing caves, human remains and crystal formations take on an uncanny shared sentience. While Mochu and Aydın’s Cappadocian geologies are made of the deaths of supervolcanoes, these caverns, of the Wookey Hole Caves, are a graveyard of another kind. Over the millennia, marine organisms accumulated in their trillions into limestone tombs: ancient seabeds formed of the compressed bodies of crinoids, coccolithophores, ammonites, belemnites and foraminifera. In Underland, MacFarlane describes this corner of Somerset as a ‘dance of death and life’: transforming minerals from the water to create ‘intricate architectures’ of their skeletons and shells, the sea creatures later become rock that is eroded away to again nourish the sea. A life cycle of multispecies in which ‘mineral becomes animal becomes rock’. Stone Tape Theory, popularised by 19th-century psychics, hypothesised that mental impressions could be imprinted onto rocks and other items through projected energies, recorded in a mineral language and ‘replayed’, like a tape recording, in the future under certain conditions (a pseudoscience also deliberated over by Mochu’s anime investigators). Look Then Below listens for the secreted voices of those bodies embalmed in their rocky reality.

Caves perhaps have much in common with black holes in cultural consciousness: powerful and deadly, drawing matter, energy and bodies into an infinite darkness. Conversely, NASA astronomers recently discovered a supermassive black hole believed to have sparked the births of stars millions of trillions of miles away, across multiple galaxies, nurturing them with hot spewing gas, energising jets of particles in the surrounding matter. Both nourishing and feeding on their surroundings, the caves of Look Then Below seem to both swallow time and emit renewed energy into a thriving pulsating ecosystem of the glowing rocks. Human remains merge with their deep-time geological cohabitants, compacting eras into an eerie unison. Organic bodies discarded, surplus to requirements, sentience has been absorbed into a mineral existence. In his writing on solidarity with the non-human, Timothy Morton writes: ‘I cannot speak the ecological subject, but this is exactly what I’m required to do. I can’t speak it because language [...] is fossilised human thoughts.’ Just beyond the grasp of our recognition, Rivers’s effervescent caves invert Morton’s predicament: intelligent thought emanates from the glistening rocky walls, sometimes legible through echoed whispers, sometimes murmured in vibrations beyond our linguistic limitations, speculatively decoding the language written in these rocks, ‘bubbling out of the limestone by ancient fluids’. Beyond the life of our species, the hidden geological voices speak from the deep past reaching out to an intelligent being somewhere in the deep future, or a different temporality altogether, at once existing in the past, present and future.

It is among the crystal depths of cavernous underlands that Jemison’s survivors similarly find sanctuary. When her future land thrashes about angrily, the Orogenes ‘sess’ downwards, deep into the bedrock; they take stock, sensing the lay of the land below, calmly steadying and soothing the reverberations as they find a shared affinity with it. Perhaps we too can find ways to align ourselves with the geological, to soothe a possible symbiotic future. As Michael Serres has written, within the underland, ‘Thousands of materials hold millions of exchanges and conduct billions of reciprocal transformations’, and as such the cave demonstrates how we and other living entities are collectively formed: the ever-transforming fabric of the planet. He continues: ‘I too am a diamond, made of hard carbon, occasionally pure, transparent, or grainy [...] emanating from the various things in the world as well as thousands of people and living entities one comes into contact with. I too am a cornucopia.’ One of my most memorable studio visits entailed being huddled in a storm drain with Augustas Serapinas. From this dark retreat from the outside world, we could contemplate the wonders of the outside without the noise of contemporary life. We were surrounded in the darkness by mud, stone and water, and the other end of the tunnel opened onto a bright sunlit river flowing past, preventing our eyes from adjusting to the dark. I felt like we were inside a shared earthly consciousness. - Sophie J Williamson

https://www.artmonthly.co.uk/magazine/site/article/underlands-by-sophie-j-williamson-april-2021

Cybernetic prostheses meet art history, cartoon physics and the acid-woozy ruins of 1960s counterculture in Mochu’s cinematic universe. The Indian artist’s output spans multiple media, but he is best understood as a writer with a movie camera. Text overflows his films like water from an infinity pool, taking shape as accompanying essays and lecture performances. Like the works of Soviet film-director Dziga Vertov, his videos eschew straightforward narrative exposition for a kind of database cinema of accumulated fragments and a liberal use of special effects. And although nearly a century of technological development separates them, both filmmakers evince an interest in modes of perception and transhumanist utopianism. But whereas Vertov understood the camera lens as a second eye, in Mochu’s hands it becomes something groovier and weirder, tapping into transhistorical astral planes to function more like a third one.

Mochu was born in Kerala, grew up around India and is currently based between Delhi and Istanbul. He is wary of the identitarian pitfalls that await non-Western artists, and uses this childhood nickname over his legal one for the opacity it grants, explaining over email that “I like the lazy ambiguity it affords (gender, species, ethnicity, collective/individual), nothing is clear in it.” He studied animation and communication design at Delhi’s National Institute of Design during the early 2000s, a time when celluloid was being discontinued and the industry was moving towards nonlinear digital editing. Mochu arrived at experimental cinema via a process of elimination – “I wasn’t interested in ads,” he explains over Skype – and never formally trained as an artist. Later stints at the now-defunct Sarai Institute, set up by Raqs Media Collective in Delhi, and Ashkal Alwan’s Homeworks Program in Beirut further honed his interest in critical theory (Chris Kraus, Kodwo Eshun, Reza Negarestani, Jalal Toufic) and technology.

Nevertheless, he grew up around art: his father was a painter, and the family spent some time at the Cholamandal Artists’ Village on the outskirts of Chennai. It was India’s largest artist colony and the birthplace of the Madras Movement of Art, which differs from the better-known vanguardists of Indian modernism, the Bombay Progressives, for its utter rejection of European masters in favour of local art movements and indigenous craft forms. Decades later, in 2015, Mochu would make A Gathering at the Carnival Shop, about one of the artists at Cholamandal. The film orbits the curious 1973 disappearance of enigmatic outsider artist K. Ramanujam – who, according to the film, may have turned into a black dog or a hat – but is equally a portrait of place. It eschews documentary conventions for a conversational, exploratory tone that lingers on archival images, artwork and Ramanujam’s fellow artists, now old men, who reminisce at unedited length.

There is a sense throughout Mochu’s practice that art history unfolds from topography. An early short video, Painted Diagram of a Future Voyage (Who Believes the Lens?) (2013), posits a speculative Indian landscape derived from aquatints produced by colonial painters Thomas and William Daniells. Here, buildings are picked up, distorted as if they’ve taken a timespace-shearing lap around the galaxy – anamorphosis is reframed as the distorted gaze of Empire – to create a sci-fi alien landscape that is as unmoored from reality as the Daniellses’ Orientalist fantasies. Another short, Mercury (2016), similarly intervenes in an art-historical landscape through cut-and-paste, zinelike animation, this time the Mughal court painter Ustad Mansur’s miniatures featuring plants and animals.

More recently, Mochu has been thinking about the way in which freeports and financial speculation alter flows of linear time – art futures, instead of art history – by locking down the future, much as an art museum safeguards the past. He is adapting a 2018 lecture-performance on the subject into a book, which will be copublished by Reliable Copy and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. Another lecture performance, Toy Volcano, whose presentation was postponed by Lebanon’s 2019 October Revolution backing into the pandemic, considers the deep time of geology – and Anthropocenic change as special effects – via Japanese manga, trypophobia and two bizarre, thoroughly enjoyable tales.

Mochu’s early influences come from the Indian experimental cinema tradition, and include Amit Dutta and Kamal Swaroop, both of whom he credits with expanding his sense of what was possible as a student. As for Vertov, Mochu cites the Soviet filmmaker’s contemporaries Georges Méliès, Segundo de Chomón and later Dadaist and Surrealist collage films as stronger influences, as well as Chris Marker and certain essay films from Orson Welles, David Blair and Jean-Luc Godard, which extend the Vertovian tradition and, “while sustaining a documentary layer, also employ a heavy layer of trick imagery and effects”. He is also particularly drawn to science fiction, such as work by the Russian authors Arkady and Boris Strugatsky and the Polish Stanisław Lem, which he finds beautiful in their abstraction, noting that the genre was widely available (in translation from Russian) in the children’s section of Marxist bookstores. “There’s an ontological confusion about things, and you don’t know whether a thing is an object or a person. This kind of fundamental confusion I think is very well done in the Eastern European context more than in the American or French,” he says. This ontological confusion equally pervades Mochu’s practice, as in the example of Ramanujam, the artist who became a black dog and/or a hat.

It’s an interesting point: technological development tends to be so bound up with narratives of the nation that a country’s sci-fi inevitably reflects its national mythologies even as it might be critical of them. Consider the individualist, techno-utopian impulses of American science fiction, for example, which does nothing so much as recast Manifest Destiny for space exploration. In contrast, Mochu points to the existential dread that pervades Soviet novels as well as their particular literary devices created to circumvent the restrictions imposed on those writing from behind the Iron Curtain. Given the unprecedented crackdowns on personal and press freedoms happening in India today, from cutting broadcast media and jailing journalists who publish stories critical of the ruling party, to the ongoing epidemic of caste-based sexual violence, I wonder whether more Indian artists might not find Soviet science fiction instructive.

At the same time, Mochu is careful to describe his own work as technofiction, explaining that “most of my works are dealing with technology rather than science: technical device, some philosophy of technology, however badly misunderstood that might be, and technoscientific imaginaries”. He is perplexed to find little in the way of a native philosophy of technology in India beyond the kind of gurus-and-jugaad spiritual-meets-technopreneurial schlock you might spot at airport bookshops the world over. He cites Yuk Hui’s recent work on China as an exemplary analogue here, and at one level his practice might be understood as a journey to figure out what that might look like. The California Ideology may have lost its sheen as efforts are made to hold Big Tech accountable for their misuse of consumer data and its lax monitoring of political ads and disinformation, but it is alive and well in IT hubs like Bangalore and ‘Cyberabad’, and in the ethos of the Indian Century. Mochu is currently working on a film about Hindu fundamentalists and their successful takeup of ‘Dark Enlightenment’ (a neoreactionary movement founded by Nick Land and Curtis Yarvin) alt-right tactics to manipulate public sentiments.

Of course, the exchange goes both ways. “In India we’ve been peddling and selling spiritualism for centuries,” the artist remarks. Cool Memories of Remote Gods (2017) is a kaleidoscopic nocturnal trip, the kind where you’re not sure what exactly you’ve ingested, dissecting the corpse of the 1960s hippie trail to trace the linkages between its appropriations of suitably ancient Indian mysticism and the development of the personal computer. Mochu was careful to emphasise spirituality over religion here, deciding not to film in Varanasi for this reason and instead choosing the tiny-but-sacred (to both Hindus and Sikhs) remote desert city of Pushkar. Drugs, intimated via heavy manipulation, are compared to personal technologies – or is it vice versa? – even as old posters, psychedelic paraphernalia and the generalised abjection of the ageing hippie signal the movement’s bankruptcy. Commissioned for the 2017 Sharjah Biennial, it was first shown in a darkened room in a building shaped like a flying saucer; I didn’t quite have my own spiritual epiphany, but it was perfect. - Rahel Aima

https://artreview.com/remote-gods-indian-filmmaker-mochu-weird-cinema/

Mochu. b. 1983, India. Currently in Delhi and Istanbul.

Mochu works with video and text arranged as installations, lectures and publications. Ideas around anxiety, futurity, and weird selfhoods, particularly emerging out of large-scale technoscientific paradigms and the knots of international mobility, feature prominently in his works.

The video speculates a new landscape composed from the aquatints of India, made by the British landscape painters Thomas and William Daniells (1749-1837). All human and architectural elements seem to have escaped the perspectival gaze of the camera obscura with which the paintings were constructed. Similar to the technique of Anamorphosis in Renaissance painting, the digital skew frees the structures from time, gravity and the picture-plane.

Mochu is an experimental film-maker and artist based in India. He often works with text, drawings and video, combining ideas of techno-fiction, quasi-mythology and art history. His recent projects deal with specific instances in the history of visual art, with a focus on technological fictions and speculative imagery that are often embedded in them – some examples being the aquatints of the British landscape painters Thomas and William Daniells and the Indian painter K. Ramanujam. The ongoing project is a multi-platform science-fiction work on inorganic sentience, mystical collectives and techno-orientalism. He is currently on a fellowship at the Home Workspace Program at Ashkal Alwan, Beirut, and his work has been exhibited at various venues such as Transmediale BWPWAP, NGMA Bangalore, WEYA Nottingham, Collectif Jeune Cinema, Khoj International Artists Association and The Royal Academy of Arts.

Interview with Mochu by Charu Maithani

Charu Maithani [CM]// You describe ‘Who Believes the Lens?’ as a ‘collision of Orientalism and science fiction’. What are the forces at play between Orientalism and science fiction resulting in their ‘collision’?

Mochu// The phrase emerged out of some of my readings on the history of science fiction and its conceptual affinities to the colonial program. The construction of new ‘worlds’ in numerous science fiction stories and their appropriation of the notions of race, landscape and future, often mimicked the ideological mechanisms of the colonial state. The articulation of the Orient as a landscape of fantasy involved a similar procedure of projecting evolutionary theories and anthropological discourses that supported specific programs of military and economic conquest. The Daniells’ paintings, for example, developed exclusively for consumption in Britain and presented India as a primitive world of pre-technological charm. In my video, the distorted post-technological forms create ruptures in this pristine fantasy and form a new universe.

CM// In terms of technique, Thomas and William Daniell used Camera Obscura to convey a perspective to the aquatints. In ‘Who believes the Lens?’, you have skewed the perspective of the objects in the images, subverting the definition of ‘Orientalism’ as something that can be studied, depicted and reproduced. What do you think about this?

Mochu// The skewing of perspective points to the Early Renaissance technique of Anamorphosis, where certain elements within paintings were distorted systematically to afford a privileged viewing angle for the viewer to contemplate them. This was simultaneously a way of coding information as well as a device to propel the viewer out of the restrictive spatio-temporal framework of the perspectival gaze implicit in the paintings. This establishment of perspectival gaze and a fixed position for the viewer set the stage for maps and lens-based devices crucial to the conquest of new territories by colonising forces, whereas the anamorphic forms seem to slice through the ideology of such a vision. In ‘Who believes the Lens?’ I used the skewing and distorting tools in digital image-editing softwares to create a visual discontinuity that resembles this older technique. When imposed on the Daniells’ paintings that were made with the aid of a Camera Obscura, a device that realizes the most fundamental idea of lens-based optics, the digital distortions subvert the fixed gaze and liberates the viewer from its naturalistic arrest.

CM// You work in different mediums, video, drawing, writing, how do they influence the articulation of your thought and imagery. Are you tempted to use text in video or drawing in video?

Mochu// The relation between the word, the still and the moving image has been explored in various capacities in most of my works, including my recent film on the painter K. Ramanujam. I feel that imagination is activated most effectively when the synchrony between the word and image is constantly shifting.

CM// Science fiction seems to be a recurring theme in your work. Your earlier work ‘Wake’ presents the memories of a village where a time machine has crashed and your latest work on the painter K. Ramanujam also lays emphasis on the fantasy worlds created by him. In your drawing based and literary work also science fiction and fantastical images are seen. Could you comment on the science fiction imagery created by you, the influence of pop culture science fiction on it and the dystopian imagery of future?

Mochu// Science fiction has been a fascination since childhood. Over time though, as I started doing basic background reading while working on my own stories, scripts and ideas. The theories and ideas within science and art history started to seem more interesting than my narratives. This continues to remain so and because of that I tend to often develop highly conceptual science-fictional atmospheres that rely on abstract scientific and aesthetic concepts rather than naturalistic, dramatic plots. Many of these resist concrete images, so the struggle to develop an aesthetic for it is an interesting challenge that involves using words and images in varying combinations. However, the visual language in both my drawings and films retain some pop culture influences from music videos and mythological comic books among others. When juxtaposed with theoretical ideas, it produces a strange asynchrony that appeals to me.

CM// Can we talk a little bit about the usage of sound in your work. ‘Wake’ wonderfully presents the soundscape of the village and the time machine. The soundscape is a narrative element there. In ‘Who believes the Lens’ you do not use sound, is there a conceptual reason behind it?

Mochu// ‘Wake’ presents a highly fragmented dystopia and the sound was approached as a noise-narrative that leads to the time-machine-camel and the subsequent nostalgia for the village. The atmosphere of anxiety and panic in the film relies heavily on these noise particles to eventually compose the dystopia. In ‘Who Believes the Lens?’ though, I wanted to maintain the sense of time and volume implied in silent painted surfaces rather than add a new universe to it through sound.

https://proprioception.in/painted-diagram-of-a-future-voyage-who-believes-the-lens-by-mochu/

Cool Memories of Remote Gods (Machinic Elixir - Improvisation Two)

Digital video. 14 mins 48 secs. 2017

Commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation for Sharjah Biennial 13, 2017

Set in the remnants of hippie trails in India, the video draws from the history of 1960s counterculture groups and their appropriation of spiritual ideas as a phenomenon contemporaneous with the development of the personal computer and cybernetics. No longer as active as they once were, these trails still bear the signs of the techno-fictional — overlaid with ancient spiritual regimens. As computers proposed that machine activity could replace the mind, counterculture considered whether religious or mystical experience could be recreated through technical means, as customisable 'internal technologies'. But however, this imagined ‘Empire of Equilibrium’ - the once-aspired-to state of universal harmony - has now been reduced to psychedelic posters, cheap reworks of surrealist paintings and new-age mixes of religio-techno-fusion music. The hippie trails and their associated symbolism reveal a decaying corpse, but one that has a propensity towards some kind of vampiric animation. The nature of this animation and its resurrectionary special-effects form the central schematic of the video.

The video forms Improvisation Two of the ongoing project Machinic Elixir. The project aims to develop fictions or propositions based on the decay of some of the techno-utopian impulses of the 1960's-70's and the mutations that emerge in the wake of its fallout. Each improvisation of the project examines different aspects of this decaying utopianism and the anomalous processes that power its shape-shifting qualities.

A Gathering at the Carnival Shop

Digital Video. 35 mins. 2015

Supported by India Foundation for the Arts

Early morning, 1973, close to the sea; the artist K.Ramanujam disappears or perhaps turns into a black dog. The place is by the coast of Madras, at the Cholamandal Artists' Village, where Ramanujam lived. At times he lived even within his paintings and drawings, though rarely without his hat. The hat too was seen outside, sometimes in a photograph, or as a gift from someone or hovering by the sea. Meanwhile the pillars, the facades, the giant tunnels grow entangled with clouds, acid holes and insects. Speculations emerge, on forgotten materials, decay and immortality.

Painted Diagram of a Future Voyage (Who believes the lens?)

5 mins loop. 2013

The video was conceived as a part of a project exploring collisions of orientalism, colonialism and science fiction. It speculates a new landscape composed from the aquatints of India, made by the British landscape painters Thomas and William Daniells (1749-1837). The Daniells' paintings, developed exclusively for consumption in Britain, presented India as a world of pre-technological charm and primitive appeal. In the video, the distorted floating forms create ruptures in this pristine fantasy and form a new universe. The skewed forms recall the Early Renaissance technique of Anamorphosis, where certain elements within paintings were distorted systematically to afford a privileged viewing angle for the viewer to contemplate them. This was simultaneously a way of coding information as well as a device to propel the viewer out of the restrictive spatio-temporal framework of the perspectival gaze implicit in the paintings. In the video, the skewing and distorting tools in digital image-editing softwares have been used to create a visual discontinuity that resembles this older technique. When imposed on the Daniells' paintings that were made with the aid of a Camera Obscura, the digital distortions interrupt the fixed gaze and liberates the viewer from the naturalistic arrest.

HD Video. 26 mins. Stereo. 2022.

Produced by Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst with a site-specific 4-channel version exhibited as part of the artist's solo show Sentient Picnic.

GROTESKKBASILISKK! MINERAL MIXTAPE indexes an anomalous crash site of philosophy where online subcultures, cyberpunk ruins and imperial nostalgia arrange themselves into a prismatic history full of memory errors, discognitions and techno-utopian fantasies. Glinting through this conceptual wreckage is a peculiar anti-egalitarian map of time, closely allied to the genre tactics of science fiction and horror, as well as the managerial protocols of big tech. Scavenging the scene are the more fundamental but incompatible impulses of rationality and civilization, locked in an almost constant state of combat choreography.

The transformation of the space of the internet, from its early countercultural strains to the highly corporatised versions of today, hosts within it some sweeping civilizational narrations: theories on the decline of empires, regressions of historical progress, fears of technology and the clash of cultures. Western civilizational collapse is a prominent fiction of this kind, in the wake of which historical progress is feared to be sliding dangerously off the road. And reconfigured within this flight of history is the imaginary of the East. Big cities of East Asia, Persian Gulf or Central Asia - with their rapid technological developments - begin to stand-in for the expansion of capital without the resistance of human history, namely its paradigms of justice or rights. However, techno-futurist projections have consistently obsessed over the humorous, low-resolution worlds of anime chatrooms, cartoon mascots and meme shitposting. This obsession catalogues a planetary index of material horror, spiralling out from the early days of Japanese otaku culture to the spread of Chinese industrial exports. Through a corruption of 3D real-estate renderings, Bollywood sounds, martial-arts games, and mythological comics, GROTESKKBASILISKK! MINERAL MIXTAPE looks at apolitical techno-subjectivity on the internet and its duplicitous mockery of social institutions, political progress and cultural freedom. In the course of this history appear lost faces, defiled statues, demonic cats, and pestilential affect-objects.

Toy Volcano

40-45 mins. HD Video + Lecture Performance, 2019

Produced by Ashkal Alwan in the context of Homeworks Forum 8, Beirut, 2019

A video-lecture-performance that looks at the embedding of technological media artifacts and knowledge within physical landscapes and geological phenomena at large, through a fan-fiction involving portable holes, animation theory and machinic delusions. Set in the universe of a forgotten manga, the narrative of a tourism department official plays host to counterfeit theories connecting Outsider art, suspect materials and the physics of cartoons.

Wake

MiniDV. 15 mins. 2008

Diploma Project Film, National Institute of Design

A remote village in the desert, inhabited by fleeting humans, guarded by a dreaming puppet. Flies buzz around a crashed time-machine. Noise particles infest thought and emotions. Guided by birds dead and alive, a man discovers the time-machine's flight recorder, and the memory of the village flows out.

Radius of a Wish Unfulfilled

(Machinic Elixir - Improvisation One)

Installation with a silent video loop, wall text, stills and lecture-performance

This work is a partial realisation of a system of ideas developed over 10 months during Home Workspace Program, titled Machinic Elixir. The system proposes texts, 3d-rendered stills and animations, scripts for videos and other durational components like talks and lectures. The Open Studio sessions displayed a preliminary trial or Improvisation One of these interconnected set of ideas. For example, the installation displayed here belongs to the section Dust in the larger complex of ideas displayed in the space as text. It follows the story of a group of people who gather near a hallucinogenic crater in an unspecified desert. Precognitive particles fly about in an approaching dust storm. These particles function like fleeting-improvised prosthesis, marking out new lines of ascent, descent and drift for migratory behaviour. Speculations arise over whether the crater is a womb or a sarcophagus.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.