Marc Vincenz, Mao’s Mole, Neopoiesis Press, 2013.

"China throws long shadows. Somewhere between Mao's revelation of the use of the vast Chinese masses, and between Colonel Sanders and Steve Jobs' revelation of the same masses and their use, nothing happened. The masses died, mostly, quickly in battle or slowly by toxins, and the wisdom of monks in the caves stayed the same. The masses and the monks in their caves play an ancient game in Marc Vincenz verses, a complex game of poetry Go, born of the poet's encounter with real people who are at the same time a mass. China's paradoxes breathe in his poems." - Andrei Codrescu

Mao’s Mole is a remarkable, ambitious, intellectually stimulating book, an extraordinary historical tour of modern China by one of our most brilliant poets, whose clarity of vision, elegance and command of language are astounding. “Let me tell you a secret,” one of the characters intones in the beginning. Under Marc Vincenz’s assured guidance, the reader is regaled by “ancient tales of villages passing through winter’s cold fingers, …fading into soft-snow of god-sky.” He conjures up Lewis Carroll and “would you believe it?” down the rabbit hole we go, to places where

“wind carries the ghosts

of greedy ancestors, in the afterlife

they can’t bear to be alone.”

And

“Here ice,

he says,

is metaphor for life: impossible to catch

frozen in seconds and evaporates in short winter light.”

“In China absolutely nothing is as it seems,” we’re told.

Let’s take Henry James’s words and apply them to Vincenz: he has woven himself a magic carpet.

Reader, stand on it!

The 192 poems, ingeniously tight, read like a cinematic novel.

Vincenz quotes Liu Xiaobo: “Even if I am crushed into powder, I will embrace you with the ashes.”

This will too.

Riddled with insight, at times tongue in cheek, poignant, heart wrenching and grueling, these persona poems present a multitude of voices, delightful tableaux of the mundane and fantastical that leave the reader astonished. - Hélène Cardona

The Big Forgetting

Foreword to Marc Vincenz’s Mao’s Mole (Neopoiesis Press, 2013) followed by an interview with the author, both by Tom Bradley.

At the beginning of this book our poet is climbing the Kunlun Mountains, paradise of the Taoists, mythical source of the Yellow River. All at once, “naturally, as you might expect,” an old man materializes from behind a tree. He leads our poet to the expected cave, shows him the expected book with the names and specifications of “anyone who has ever dared live.” Our poet finds his own entry, and what does it comprise? Nothing less than the 112 poems of Mao’s Mole. Subsumed under the rubric Marc Vincenz is the most exhaustive yet intimate rendering of modern China in all of Indo-European poetry. He has literally made this infinite civilization his own. It’s a just claim.

In the first poem, Cixi, the last Empress Dowager, is disdaining her “useful dolts” as they kowtow to the billiard table which Queen Victoria has given her. From there, Mao’s Mole sweeps all the way forward to the millennium we upstart occidentals quaintly call our “third.” Along the way, Mao himself, poetaster tutelary and eponymous bugaboo, makes his entrance. Still young, wan, thin and affable, he stands on top of the Exalted Mountain, and proclaims the east to be that certain notorious hue, only to wind up “vacuum-sealed, embalmed, death defying” in his crystal casket. A couple blocks away, “Starbucks yawns wide behind the knobbed doors of heaven.”

Meanwhile, naturally, as you might expect, Deng Xiaoping materializes, hawking his Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. In Marc Vincenz’s revision, the superannuated dwarf must deal with a contingent of Shaolin monks who show up at the Tienanmen Square massacre “shooting thunderbolts from their fingers.” Deng’s dictum about the glory of getting rich inspires schemes of karaoke bars in Shanghai’s old alleys; but his touted modernization fails to confiscate shards of dragon eggshells from a rural child, urbanized but not cured of feudal superstition.

As always in any Marc Vincenz book there are the lovely women, fresh with “tiny pinprick breasts like ripe buds of corn,” and, of course, the food. In this case, it’s the street stall cuisine we China hands have known so well: spitting seeds and bits of rind, where fish heads and spines lay rotting amongst flies. Accommodations are provided courtesy of hotels with names like Red Star, where you must battle the rats for rights to the apple, compliments of the manager.

Mao’s Mole has much truck with factories and their managers, for our poet himself spent ten years in that purgatory, in cahoots with bankers and party muckety-mucks, steeped in corruption of such intensity as can only be achieved in the world’s oldest continuous bureaucracy. Naturally, as you might expect, the poetry achieves some of its highest pitches under these unpoetic circumstances:

…it’s all leaching under the foundations

can’t let the shareholders know or the factory would close

I just smiled back & cheered our good health—

The world was big & cancer was everywhere

in the meat, in the bread, the sky, the unflinching earth

only in Iceland will the volcanoes get you

& then there was factory kingpin Ying

with the blue phone glued to his ear—

he who rose from the communist earth

In his previous collection, Gods of a Ransacked Century (Unlikely Books), Marc Vincenz gave us a full cosmology, from the materia prima of tachyon waves to hydrogen bombs and rocket salads. He provides nothing less in Mao’s Mole. The people of the Flowery Middle Kingdom have long considered their walled world coextensively coterminous with the cosmos, relegating any outliers to triviality and irrelevance. Marc Vincenz is one of the few barbarians who has entered and encompassed their universe.

Having lived and wandered there for some years, I can affirm that Marc Vincenz’s is the clearest, most intelligent and emotionally intense evocation of that unfathomable place I’ve ever read in verse or prose. Everything is on these pages, the poisoned as well as the pristine, all presented with hallucinatory concision by easily the strongest living poet in our language.

I interviewed Marc Vincenz recently, as follows:

3:AM: China’s long, nearly static history, climaxed with the past hundred years of political and economic upheavals, make for what must be the world’s most difficult subject to treat exhaustively. But that is just what you have done in Mao’s Mole. Did you set out to deal with the subject of national, racial and tribal metamorphosis, using China as an especially vivid and extreme example?

MV: Not at first. Individual pieces arrived sporadically: on the edges of dreams, were clipped from conversations in karaoke bars, on noodle stands, at the train station, arose as flashbacks of memories and past lives. Although each voice or image is singular, they are also born out of a communal mythology, a common “becoming” — in a way, the various characters stitched themselves together (some zigzagged, others loosely tacked themselves on). I was taken aback myself when I observed from a distance and watched the bigger picture come into focus.

About halfway through, I realized that Mao’s Mole was about far more than just the individual narratives. Yes, there were individual stories, individual characters, but there was also a basso ostinato running through the heart of the book. Each of these individuals shared an embedded and deeply rooted commonality. It took me a while to figure out what exactly that was.

3:AM: Do you want to get explicit? Will you identify that ostinato for us, or are we on our own?

MV: I am little skeptical of delving into the theory of my own creative work, but, ok, let me give it a go.

As rituals, icons, philosophies and myths move into a technological, economically-driven future, intentions are diffused; they are amended to fulfill revised and cross-purposes; they become muddied or watered-down, reinterpreted or revised and evolve (or are evolved) to fit contemporary desires. In this manner, as civilizations evolve, so too do their mythologies — as their emperors, kings, priests, dictators and elected leaders reinvent religion and social structures. This mutated iconography (although seemingly from a distant past) embeds itself in a nation’s revised (self-) consciousness, promising a better, more-balanced future with a faint whiff of the past. Perhaps this is the great deceit of what we call “civilization.”

3:AM: Socialism with Chinese characteristics springs to mind.

MV: Yes, to cite one especially unsubtle example. In a layered papier-mâché of propaganda, rhetoric and perceived history, these symbols integrate into a single entity capable of feeding upon itself; just like the multiple-celled organism, civilization splits, conjoins, mutates and evolves with multiple adaptations on multiple islands.

Perhaps at its most basic level, Mao’s Mole is a cinematic journey through China’s last hundred-or-so years, offering snapshots, incidental reflections and moments of flux across a broad spectrum of the Middle Kingdom’s citizens and their foreign guests. On wider levels, the book poses deep questions of society, identity and culture; Mao’s Mole concerns itself with the development of icons, figureheads and modern mythology in today’s China; with the making of modern nations; with our dented twenty-first century mythologies.

3:AM: It’s an understatement to call Mao’s Mole ambitious; yet the book holds together miraculously well. Each of the individual poems moves to the next according to an organizing principle that is so organic as to be suspected rather than discerned. Clearly, historical epochs, dynasties, and Five-Year Plans are part of the structure, but you have dispensed with mere chronology, to offer a deeper series of connections. Can you reveal something of your framework here, to the extent it was consciously built?

MV: Although mostly portrayed as such, history, of course is actually non-linear — at the very least in the way we perceive it. Surely personal memory and “real” history are intertwined, become distorted or magnified. I mean how much do any of us remember of our earliest years of childhood? Perhaps we recall a handful of significant moments, but are these recollections really the way things happened?

Yes, it was very tempting to follow that straight arrow of time, but it’s really the crucial moments, the so-called epiphanies, the turning points that create change and paint a personal history in the mind’s inner eye.

On another level, I realized that each of these narratives represented some of those moments that were missing from documented history—moments that would likely never receive public attention, rather part of what someone once termed, “the big forgetting.” How could these multiple journeys of so many individuals be portrayed in a linear fashion? It seemed implausible; after all, it was these individual “little epiphanies” (or little deaths) that stitched the book together, that created what you have called the organic (or perhaps biometric) structure.

And yes, just as the Chinese Communist Party’s Five-Year Plan, Mao’s Mole is a work in five movements; each movement represents an era or a wave of social, economic or emotional transition that, in turn, is followed by singular passages of discord, dispersion, acceptance and assimilation. Underpinned by the faux poetry of Mao’s propaganda, each of these movements is expressed in a layering of reflections, narratives, slogans, images, quips and asides, as a multitude of individual voices merge into one tentative organism.

Another way of thinking of the structure is to envision Mao’s Mole as a Philip Stark score in five movements — with brief intermezzos between each major movement. Like Stark, these movements begin with a simple melodic phrase, but slowly, as more tones underlie the melody, it expands, divests, until, despite (or in spite of) the ambient noise (the background radiation), the original phrase reverberates somewhere in the subconscious.

3:AM: Mao himself is the Moses of this Pentateuch, the Christ of this Gospel. You don’t respect him overmuch as a poet, but you have spelunked his labyrinthine character and provided a psychological portrait that rivals any yet written in prose. Can you talk about your conception of him as man and myth?

MV: Even the most evil genius, is a genius. Aside from Confucius and Lao Tze, Mao is without a shadow of a doubt, China’s most famous son. He’s been compared to Hitler, Stalin, Bonaparte, Tamerlane, Genghis Khan, yet he portrayed himself as a reactionary poet, a sensitive scholar and, at the same time, a man of the common folk. We know enough now from the multitude of biographies and a few dissident former Party members who have come out of the closet (and haven’t been “taken out”) that he was nothing like a common man. He lived the lush life of an emperor.

And even after all of his disasters and catastrophes, he’s still hailed as a demigod; the ultimate symbol of Chinese independence and nationalism.

Not so long ago, I asked a Beijing friend of mine if she thought his portrait might one day be taken down from Tienanmen Square. She smiled wryly and told me that it would be utterly unthinkable. Imagine if Hitler’s portrait still stared down at you from the Brandenburg Gate — that too is unthinkable. It would defy all moral sensibilities and common sense; yet Mao, the demigod, watches over his people, above the gates of the fallen “Emperor’s” Forbidden City. If you wouldn’t know better you’d think there was some kind of a sick inside joke going on.

3:AM: And Mao fuels the book’s momentum?

MV: Loosely speaking. Each of Mao’s Mole‘s movements is derived from Mao’s own propaganda machine — as his empire rises and falls, and rises and falls again. The book closes with the foreshadowing of a probable Second Coming — and just as other civilizations have begged their gods return, so too Mao’s spirit is requested to arise and lead his good comrades back into the red light, into the good fight.

3:AM: One of the great delights of this collection is the cast of characters, each drawn with the detail and depth one usually associates with novels. Of course, each story is unique and worthy of being told in its own right, but tell us who some of your favorite characters are, and what function you see them serving in the greater structure.

MV: I suppose it’s only through this wily and varied cast of characters that the true picture can emerge. No, no favorite. They all have their role to play.

3:AM: How about if I suggest some of my own favorites? I am thinking of the young man in “The Analects of Wu Wei: Virtuous Dog Meat,” who extolls the Taoist virtues of eating dog while driving to work in a Mercedes. Another vivid personage is the eponymous “Citizen Julius Wong,” the one-armed ex-Communist Party cadre now settled on the island of Fiji, who advises rebel generals and swims with parrot fish. There’s the “Tai Chi Master” who practices his art to produce nuclear fission; Lu Xi, the poor factory line worker in “Legs, Hands, Fingers,” who has lost the feeling in her hands and believes herself to be transforming into a serpent: and the businessman in “While Facing the Urinal” who is offered an assassin’s services while trying to urinate.

MV: Yes, these are all people struggling to come to terms with the same morphing mythology: five-thousand-plus years of history condensed in the metaphor of the Cultural Revolution — a quintessential “rethinking” of all that ever was.

Each character, phrase or passage is a symbolically linked thread of a continually evolving web of convention, misinformation and misconstruction — and yet, all of these individuals’ fates are reflected in some skewed sense of the primordial in a modern beauty: one among many nations facing a schizophrenic future.

3:AM: You know China at all levels, as only an expatriate can, and an adventurous expatriate at that. If you think it won’t taint readers’ enjoyment of Mao’s Mole, please tell us voyeurs something about any autobiographical truck you might have had with the Flowery Middle Kingdom: formative prepubescent traumas, travels, misadventures, Sino-fornication and so forth. For example, I have heard that you were actually born in the neighborhood, and at a key moment in their history.

MV: I don’t know about all levels. I don’t believe anyone can ever know a place, a race, a tribe or a nation, and particularly one as vast, varied and ancient as China. Expatriate? Maybe. But then again, I was born in the Middle Kingdom, so does that make me Chinese? If not in race or culture, perhaps in spirit? You’d have to ask my Chinese friends.

3:AM: Even John Paton Davies went to his grave a waiguoren.

MV: True. Shortly after I came into the world, Mao’s Cultural Revolution was in full-on class struggle behind the bamboo curtain. Even in our “colonial jewel” that was Hong Kong, Maoist separatists were chanting revolutionary slogans outside capitalist factories, planting bombs down at Victoria Harbor, tossing Molotov cocktails into bourgeois shop fronts.

Mum’s father (I called him Gung Gung, the Cantonese for grandfather) had been posted to the colony just after World War II. His official task was to map Hong Kong and all its outlying islands and territories; as I came to find out later, his unofficial detail was to keep an eye out for revolutionary activities in border areas. Gung Gung was one of the very few British government employees given permission to learn what the other civil servants called “a rather distasteful tongue.”

3:AM: Some of the most fascinating poems in the book pertain to the pursuit of capitalist enterprises deep inside the world’s hugest communist dictatorship. What is your background in this delicate field of endeavor?

MV: My own father entered into a business partnership with a Shanghai businessman who had a penchant for bloody steaks and Peking Opera, and, who had fled China’s Revolution in the 50s. Strangely, despite his having fled the Republic, this Shanghai businessman still had notable connections within the Party. He and Dad built a business selling raw materials (from as far afield as the US, Canada, Brazil, Chile, South Africa and Tasmania) to the Communist Party and its singular ministries. (In those days all business in China was centralized: one ministry, one commodity.)

No matter where we lived — Hong Kong, Zurich, New York, London — there was hardly a month we didn’t have a cadre or comrade visiting our home. (My mother made sure we had a good stock of corn on the cob. It seemed to be a Party favorite.) Already in these years, the late 60s and 70s, Mao’s Party Line crept surreptitiously into our daily conversations. And in the 80s, when we lived in Connecticut and Dad was working in New York, we were sure our phone lines were being tapped on both sides. At his offices, Dad received regular visits from Men in Black. An ongoing family joke was a question that had been frequently posed to Dad: “Mr. Vincenz are you a member of the Communist Party?”

In the nineties, after having worked for businesses in Hong Kong and China myself, I finally ventured it on my own. I spent the good part of the late nineties and early two-thousands living and working in and out of Shanghai and Beijing, where I reluctantly tumbled headfirst into the growing economic powerhouse that China was starting to become. Despite the echoes of Tienanmen, Deng Xiao Ping’s “Get Rick Quick” scheme had taken a firm hold. Possibly one of the first lessons I learned first-hand is that in China absolutely nothing is ever as it seems.

3:AM: Your poetry derives richness and energy from the gigantic contradictions China poses on the world stage. How do you manage to draw such immediate and personal poetry from these economic, political and historical tectonics?

MV: China is, of course, one of the most culturally and historically significant civilizations on our planet, and has much to offer the open-minded. Yet even now, the shadow of Mao’s legacy hangs heavy over the Middle Kingdom. Guy Sorman, French economist and sinologist has said: “The Propaganda Department functions with ruthless efficiency, making gullible foreigners accept unquestioningly whatever it chooses to put out: economic statistics that cannot be verified, trumped-up elections, blanked-out epidemics, imaginary labor harmony, and the purported absence of any aspiration for democracy.”

Of course, you can never know a people or a nation. And despite my many experiences within China and with her citizens, I will always remain an outsider; yet my impressions of these people, their landscapes, heartaches and laughter — and, above all, their ongoing attempt to come to grips with an ancient legacy, with Communist doubletalk and the current Party’s proto-Marxist capitalism (a dichotomy if ever there was one) — continues to baffle and astound me.

I lived close to my Chinese colleagues and friends, broke bread with them, shared tears with them, consoled and laughed with them. How could I not become personally entangled in their lives? Although few of the poems refer to specific people (you know who you are), all of them are shadows or ghosts of people I have known on some level.

3:AM: This personal and autobiographical element has an uncanny effect on your presentation of the nation at large. The intimacy crosses over, until the unimaginable is encompassed: China becomes a microcosm. It feels strange even to say that.

MV: Absolutely. I have come to see this ultra-rapid, development of the Chinese nation from a country of emperors and robber barons, through Mao’s Cultural Revolution, to its present “economic coming of age” as a metaphor for the development of modern “civilization.” In many ways what China has survived in the last forty years is much akin to Europe’s Industrial Revolution of the mid-Nineteenth Century. And despite the fact that much of the western world believes China is on a narrow path to taking over the global economy, one must bear in mind that eighty percent of China’s population still lives in abject poverty. The money and power remains in the hands of the few — most of them well intertwined in the CCP, the Chinese Communist Party — China’s modern emperors and warlords.

3:AM: One is put in mind of your Revolutionary Commander, merciful and jocular, who addresses his troops in the penultimate poem of section one.

MV: Right. In China today, you experience the greatest extremes of wealth and poverty, injustice and indifference. For me, Mao’s Mole is not just about China’s recent history, but about how time and again, myth is being reinvented to serve the purposes of the powers-that-be under the guise of modernizing a nation.

3:AM: Excellent. How about ending this interview with a sample from Mao’s Mole?

MV: Sure, Tom. Here’s an excerpt from “Why Yang Wants to Leave Wolf Mountain”

(2)

And Yang and I become the double-entendre of all Wu county,

that staccato at the end of a Peking opera played on fields of barley—

an embarrassment for those with no faith, but a miraculous creation

for those who worship the salacious Buddha with the pot belly

like faithful Grandpa Ye who Mother says is incorrigible.

Evenings when he sips dragon brew from his chipped red cup

he chortles in our ears—in those days we have only one little Red Book—

but he sits there plunked on the edge of our bed, stomping

to scare off night mice, to ease us into our dreams with ancient tales

of villagers passing through winter’s cold fingers, of fading

into the soft-snow of god-sky, only to remerge

as black-necked cranes under our mountain’s early haze.

(3)

Grandpa Ye claims he knows each crane by name,

every unique swell and swagger, each bellow and grunt;

who flutters brazen like Great Auntie Ma or sways

on one leg like Great-grandmother Shie, and he jests

that Uncle Fu always gobbled too many fried dumplings,

croaked & ruffled his wings in a huff, but just like any crane,

deeply admired the round paleness of our spring moon

over Wolf Mountain; perhaps because it reminded him

of the crisp butter pancakes Auntie Ma would roast

on freezing winter nights, stuffed with scallions,

raisins and that secret recipe of hers for sticky brown rice. - Tom Bradley

Today I bring you The Next Big Thing from Marc Vincenz and Bill Yarrow. Marc and Bill originally posted these interviews on Facebook a few days ago. Now, in this Write, Juggle, Run exclusive, Marc and Bill re-share their interviews for the world to see.

Marc: And here we go…avec un verre du vin: in this case, a bottle of Luis Felipe Edwards from somewhere “terraced” in Chile called the Cholchagua Valley. Apparently there are herds of genetically manipulated bovines dangling amongst the grapes over there.

Le fabulous Yahia Lababidi tagged me to take part in The Next Big Thing, a series of self-interviews with poets and writers (are they the same?) which perpetrates some kind of network writer’s marketing viral infection – something I’m personally not immune to.

It works like some form of reality TV / author-self-introspection, which earnestly speaking, is not what I’m about – except for in a self-glorification, self-promotional sense. Ergo: please read books – mine or anyone else’s. Enrich the flora, enrich the mind.

Through a series of interviews rather than by association something irrational occurs and people actually start purchasing books – either that, or we’re all mildly amused by this self-glorification act.

Bill: Marc Vincenz tagged me to take part in The Next Big Thing, a series of self-interviews in which poets and writers are all asked the same nine questions. (I’ve taken the liberty to rewrite the questions to make them grammatical.)

What is the title of your book?

Marc: Mao’s Mole.

Bill: Pointed Sentences.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

Marc: The idea – or fruition – of the book came from living over ten years in China, having been born in Hong Kong during Mao’s Cultural Revolution; in essence, a distillation of any and everything that I had experienced in and with China through something like forty years of life – real or imagined.

Bill: From under the floorboards. [translation by Constance Garnett.]

What genre is your book?

Marc: Poetry, sort of. Narrative, imagined, persona and re-lived – with a bit of extra modernist “zing” thrown in to the mix.

Bill: The first one.

If your book was made into a movie, what actors would you choose to play the part of your characters?

Marc: Ah. If Yul Brynner were still alive, he should be the lead role: the revolutionary outsider continuously trying to adapt to his circumstances – with failed consequences; someone like the character he played in the The Brothers Karamazov – a kind of James Dean of the Russian Revolution. Mao would most certainly be played by Peter Sellers, as would the Empress Dowager and a minimum of five characters in the book. Terry Gilliam would have directed the movie version.

Bill: Lya de Putti, Maria Falconetti, Vera Baranovskaya, and Jerry Mathers as “the Beaver.”

What is a one-sentence synopsis of your book?

Marc: We are all but microbes in the palm of a giant.

Bill: “the mind as Ixion” (Pound, Canto CXIII)

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

Marc: Four or five years.

Bill: How long did it not take?

Who or what inspired the writing of your book?

Marc: China, the world. Conformity. The modern, brand-absorbed world we live in. Myths and mythology. Ten plus years living in China; forty plus years experiencing China from a distance or close up.

Bill: The smashing of my windshield by a flying wrench.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

Marc: Honestly speaking although the over-arching fascination appears to be with China and its modern history, this book is about how icons come about; about how mythology is created, about how modern life is lived. Mao’s Mole is your mole – even though you may not yet know it. This book is about how an icon, becomes a mole, becomes a logo.

Bill: It’s written in “gangnam” style.

Who published or will publish your book? - Nathaniel Tower

At the beginning of this book our poet is climbing the Kunlun Mountains, paradise of the Taoists, mythical source of the Yellow River. All at once, “naturally, as you might expect,” an old man materializes from behind a tree. He leads our poet to the expected cave, shows him the expected book with the names and specifications of “anyone who has ever dared live.” Our poet finds his own entry, and what does it comprise? Nothing less than the 112 poems of Mao’s Mole. Subsumed under the rubric Marc Vincenz is the most exhaustive yet intimate rendering of modern China in all of Indo-European poetry. He has literally made this infinite civilization his own. It’s a just claim.

In the first poem, Cixi, the last Empress Dowager, is disdaining her “useful dolts” as they kowtow to the billiard table which Queen Victoria has given her. From there, Mao’s Mole sweeps all the way forward to the millennium we upstart occidentals quaintly call our “third.” Along the way, Mao himself, poetaster tutelary and eponymous bugaboo, makes his entrance. Still young, wan, thin and affable, he stands on top of the Exalted Mountain, and proclaims the east to be that certain notorious hue, only to wind up “vacuum-sealed, embalmed, death defying” in his crystal casket. A couple blocks away, “Starbucks yawns wide behind the knobbed doors of heaven.”

Meanwhile, naturally, as you might expect, Deng Xiaoping materializes, hawking his Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. In Marc Vincenz’s revision, the superannuated dwarf must deal with a contingent of Shaolin monks who show up at the Tienanmen Square massacre “shooting thunderbolts from their fingers.” Deng’s dictum about the glory of getting rich inspires schemes of karaoke bars in Shanghai’s old alleys; but his touted modernization fails to confiscate shards of dragon eggshells from a rural child, urbanized but not cured of feudal superstition.

As always in any Marc Vincenz book there are the lovely women, fresh with “tiny pinprick breasts like ripe buds of corn,” and, of course, the food. In this case, it’s the street stall cuisine we China hands have known so well: spitting seeds and bits of rind, where fish heads and spines lay rotting amongst flies. Accommodations are provided courtesy of hotels with names like Red Star, where you must battle the rats for rights to the apple, compliments of the manager.

Mao’s Mole has much truck with factories and their managers, for our poet himself spent ten years in that purgatory, in cahoots with bankers and party muckety-mucks, steeped in corruption of such intensity as can only be achieved in the world’s oldest continuous bureaucracy. Naturally, as you might expect, the poetry achieves some of its highest pitches under these unpoetic circumstances:

…it’s all leaching under the foundations

can’t let the shareholders know or the factory would close

I just smiled back & cheered our good health—

The world was big & cancer was everywhere

in the meat, in the bread, the sky, the unflinching earth

only in Iceland will the volcanoes get you

& then there was factory kingpin Ying

with the blue phone glued to his ear—

he who rose from the communist earth

In his previous collection, Gods of a Ransacked Century (Unlikely Books), Marc Vincenz gave us a full cosmology, from the materia prima of tachyon waves to hydrogen bombs and rocket salads. He provides nothing less in Mao’s Mole. The people of the Flowery Middle Kingdom have long considered their walled world coextensively coterminous with the cosmos, relegating any outliers to triviality and irrelevance. Marc Vincenz is one of the few barbarians who has entered and encompassed their universe.

Having lived and wandered there for some years, I can affirm that Marc Vincenz’s is the clearest, most intelligent and emotionally intense evocation of that unfathomable place I’ve ever read in verse or prose. Everything is on these pages, the poisoned as well as the pristine, all presented with hallucinatory concision by easily the strongest living poet in our language.

I interviewed Marc Vincenz recently, as follows:

3:AM: China’s long, nearly static history, climaxed with the past hundred years of political and economic upheavals, make for what must be the world’s most difficult subject to treat exhaustively. But that is just what you have done in Mao’s Mole. Did you set out to deal with the subject of national, racial and tribal metamorphosis, using China as an especially vivid and extreme example?

MV: Not at first. Individual pieces arrived sporadically: on the edges of dreams, were clipped from conversations in karaoke bars, on noodle stands, at the train station, arose as flashbacks of memories and past lives. Although each voice or image is singular, they are also born out of a communal mythology, a common “becoming” — in a way, the various characters stitched themselves together (some zigzagged, others loosely tacked themselves on). I was taken aback myself when I observed from a distance and watched the bigger picture come into focus.

About halfway through, I realized that Mao’s Mole was about far more than just the individual narratives. Yes, there were individual stories, individual characters, but there was also a basso ostinato running through the heart of the book. Each of these individuals shared an embedded and deeply rooted commonality. It took me a while to figure out what exactly that was.

3:AM: Do you want to get explicit? Will you identify that ostinato for us, or are we on our own?

MV: I am little skeptical of delving into the theory of my own creative work, but, ok, let me give it a go.

As rituals, icons, philosophies and myths move into a technological, economically-driven future, intentions are diffused; they are amended to fulfill revised and cross-purposes; they become muddied or watered-down, reinterpreted or revised and evolve (or are evolved) to fit contemporary desires. In this manner, as civilizations evolve, so too do their mythologies — as their emperors, kings, priests, dictators and elected leaders reinvent religion and social structures. This mutated iconography (although seemingly from a distant past) embeds itself in a nation’s revised (self-) consciousness, promising a better, more-balanced future with a faint whiff of the past. Perhaps this is the great deceit of what we call “civilization.”

3:AM: Socialism with Chinese characteristics springs to mind.

MV: Yes, to cite one especially unsubtle example. In a layered papier-mâché of propaganda, rhetoric and perceived history, these symbols integrate into a single entity capable of feeding upon itself; just like the multiple-celled organism, civilization splits, conjoins, mutates and evolves with multiple adaptations on multiple islands.

Perhaps at its most basic level, Mao’s Mole is a cinematic journey through China’s last hundred-or-so years, offering snapshots, incidental reflections and moments of flux across a broad spectrum of the Middle Kingdom’s citizens and their foreign guests. On wider levels, the book poses deep questions of society, identity and culture; Mao’s Mole concerns itself with the development of icons, figureheads and modern mythology in today’s China; with the making of modern nations; with our dented twenty-first century mythologies.

3:AM: It’s an understatement to call Mao’s Mole ambitious; yet the book holds together miraculously well. Each of the individual poems moves to the next according to an organizing principle that is so organic as to be suspected rather than discerned. Clearly, historical epochs, dynasties, and Five-Year Plans are part of the structure, but you have dispensed with mere chronology, to offer a deeper series of connections. Can you reveal something of your framework here, to the extent it was consciously built?

MV: Although mostly portrayed as such, history, of course is actually non-linear — at the very least in the way we perceive it. Surely personal memory and “real” history are intertwined, become distorted or magnified. I mean how much do any of us remember of our earliest years of childhood? Perhaps we recall a handful of significant moments, but are these recollections really the way things happened?

Yes, it was very tempting to follow that straight arrow of time, but it’s really the crucial moments, the so-called epiphanies, the turning points that create change and paint a personal history in the mind’s inner eye.

On another level, I realized that each of these narratives represented some of those moments that were missing from documented history—moments that would likely never receive public attention, rather part of what someone once termed, “the big forgetting.” How could these multiple journeys of so many individuals be portrayed in a linear fashion? It seemed implausible; after all, it was these individual “little epiphanies” (or little deaths) that stitched the book together, that created what you have called the organic (or perhaps biometric) structure.

And yes, just as the Chinese Communist Party’s Five-Year Plan, Mao’s Mole is a work in five movements; each movement represents an era or a wave of social, economic or emotional transition that, in turn, is followed by singular passages of discord, dispersion, acceptance and assimilation. Underpinned by the faux poetry of Mao’s propaganda, each of these movements is expressed in a layering of reflections, narratives, slogans, images, quips and asides, as a multitude of individual voices merge into one tentative organism.

Another way of thinking of the structure is to envision Mao’s Mole as a Philip Stark score in five movements — with brief intermezzos between each major movement. Like Stark, these movements begin with a simple melodic phrase, but slowly, as more tones underlie the melody, it expands, divests, until, despite (or in spite of) the ambient noise (the background radiation), the original phrase reverberates somewhere in the subconscious.

3:AM: Mao himself is the Moses of this Pentateuch, the Christ of this Gospel. You don’t respect him overmuch as a poet, but you have spelunked his labyrinthine character and provided a psychological portrait that rivals any yet written in prose. Can you talk about your conception of him as man and myth?

MV: Even the most evil genius, is a genius. Aside from Confucius and Lao Tze, Mao is without a shadow of a doubt, China’s most famous son. He’s been compared to Hitler, Stalin, Bonaparte, Tamerlane, Genghis Khan, yet he portrayed himself as a reactionary poet, a sensitive scholar and, at the same time, a man of the common folk. We know enough now from the multitude of biographies and a few dissident former Party members who have come out of the closet (and haven’t been “taken out”) that he was nothing like a common man. He lived the lush life of an emperor.

And even after all of his disasters and catastrophes, he’s still hailed as a demigod; the ultimate symbol of Chinese independence and nationalism.

Not so long ago, I asked a Beijing friend of mine if she thought his portrait might one day be taken down from Tienanmen Square. She smiled wryly and told me that it would be utterly unthinkable. Imagine if Hitler’s portrait still stared down at you from the Brandenburg Gate — that too is unthinkable. It would defy all moral sensibilities and common sense; yet Mao, the demigod, watches over his people, above the gates of the fallen “Emperor’s” Forbidden City. If you wouldn’t know better you’d think there was some kind of a sick inside joke going on.

3:AM: And Mao fuels the book’s momentum?

MV: Loosely speaking. Each of Mao’s Mole‘s movements is derived from Mao’s own propaganda machine — as his empire rises and falls, and rises and falls again. The book closes with the foreshadowing of a probable Second Coming — and just as other civilizations have begged their gods return, so too Mao’s spirit is requested to arise and lead his good comrades back into the red light, into the good fight.

3:AM: One of the great delights of this collection is the cast of characters, each drawn with the detail and depth one usually associates with novels. Of course, each story is unique and worthy of being told in its own right, but tell us who some of your favorite characters are, and what function you see them serving in the greater structure.

MV: I suppose it’s only through this wily and varied cast of characters that the true picture can emerge. No, no favorite. They all have their role to play.

3:AM: How about if I suggest some of my own favorites? I am thinking of the young man in “The Analects of Wu Wei: Virtuous Dog Meat,” who extolls the Taoist virtues of eating dog while driving to work in a Mercedes. Another vivid personage is the eponymous “Citizen Julius Wong,” the one-armed ex-Communist Party cadre now settled on the island of Fiji, who advises rebel generals and swims with parrot fish. There’s the “Tai Chi Master” who practices his art to produce nuclear fission; Lu Xi, the poor factory line worker in “Legs, Hands, Fingers,” who has lost the feeling in her hands and believes herself to be transforming into a serpent: and the businessman in “While Facing the Urinal” who is offered an assassin’s services while trying to urinate.

MV: Yes, these are all people struggling to come to terms with the same morphing mythology: five-thousand-plus years of history condensed in the metaphor of the Cultural Revolution — a quintessential “rethinking” of all that ever was.

Each character, phrase or passage is a symbolically linked thread of a continually evolving web of convention, misinformation and misconstruction — and yet, all of these individuals’ fates are reflected in some skewed sense of the primordial in a modern beauty: one among many nations facing a schizophrenic future.

3:AM: You know China at all levels, as only an expatriate can, and an adventurous expatriate at that. If you think it won’t taint readers’ enjoyment of Mao’s Mole, please tell us voyeurs something about any autobiographical truck you might have had with the Flowery Middle Kingdom: formative prepubescent traumas, travels, misadventures, Sino-fornication and so forth. For example, I have heard that you were actually born in the neighborhood, and at a key moment in their history.

MV: I don’t know about all levels. I don’t believe anyone can ever know a place, a race, a tribe or a nation, and particularly one as vast, varied and ancient as China. Expatriate? Maybe. But then again, I was born in the Middle Kingdom, so does that make me Chinese? If not in race or culture, perhaps in spirit? You’d have to ask my Chinese friends.

3:AM: Even John Paton Davies went to his grave a waiguoren.

MV: True. Shortly after I came into the world, Mao’s Cultural Revolution was in full-on class struggle behind the bamboo curtain. Even in our “colonial jewel” that was Hong Kong, Maoist separatists were chanting revolutionary slogans outside capitalist factories, planting bombs down at Victoria Harbor, tossing Molotov cocktails into bourgeois shop fronts.

Mum’s father (I called him Gung Gung, the Cantonese for grandfather) had been posted to the colony just after World War II. His official task was to map Hong Kong and all its outlying islands and territories; as I came to find out later, his unofficial detail was to keep an eye out for revolutionary activities in border areas. Gung Gung was one of the very few British government employees given permission to learn what the other civil servants called “a rather distasteful tongue.”

3:AM: Some of the most fascinating poems in the book pertain to the pursuit of capitalist enterprises deep inside the world’s hugest communist dictatorship. What is your background in this delicate field of endeavor?

MV: My own father entered into a business partnership with a Shanghai businessman who had a penchant for bloody steaks and Peking Opera, and, who had fled China’s Revolution in the 50s. Strangely, despite his having fled the Republic, this Shanghai businessman still had notable connections within the Party. He and Dad built a business selling raw materials (from as far afield as the US, Canada, Brazil, Chile, South Africa and Tasmania) to the Communist Party and its singular ministries. (In those days all business in China was centralized: one ministry, one commodity.)

No matter where we lived — Hong Kong, Zurich, New York, London — there was hardly a month we didn’t have a cadre or comrade visiting our home. (My mother made sure we had a good stock of corn on the cob. It seemed to be a Party favorite.) Already in these years, the late 60s and 70s, Mao’s Party Line crept surreptitiously into our daily conversations. And in the 80s, when we lived in Connecticut and Dad was working in New York, we were sure our phone lines were being tapped on both sides. At his offices, Dad received regular visits from Men in Black. An ongoing family joke was a question that had been frequently posed to Dad: “Mr. Vincenz are you a member of the Communist Party?”

In the nineties, after having worked for businesses in Hong Kong and China myself, I finally ventured it on my own. I spent the good part of the late nineties and early two-thousands living and working in and out of Shanghai and Beijing, where I reluctantly tumbled headfirst into the growing economic powerhouse that China was starting to become. Despite the echoes of Tienanmen, Deng Xiao Ping’s “Get Rick Quick” scheme had taken a firm hold. Possibly one of the first lessons I learned first-hand is that in China absolutely nothing is ever as it seems.

3:AM: Your poetry derives richness and energy from the gigantic contradictions China poses on the world stage. How do you manage to draw such immediate and personal poetry from these economic, political and historical tectonics?

MV: China is, of course, one of the most culturally and historically significant civilizations on our planet, and has much to offer the open-minded. Yet even now, the shadow of Mao’s legacy hangs heavy over the Middle Kingdom. Guy Sorman, French economist and sinologist has said: “The Propaganda Department functions with ruthless efficiency, making gullible foreigners accept unquestioningly whatever it chooses to put out: economic statistics that cannot be verified, trumped-up elections, blanked-out epidemics, imaginary labor harmony, and the purported absence of any aspiration for democracy.”

Of course, you can never know a people or a nation. And despite my many experiences within China and with her citizens, I will always remain an outsider; yet my impressions of these people, their landscapes, heartaches and laughter — and, above all, their ongoing attempt to come to grips with an ancient legacy, with Communist doubletalk and the current Party’s proto-Marxist capitalism (a dichotomy if ever there was one) — continues to baffle and astound me.

I lived close to my Chinese colleagues and friends, broke bread with them, shared tears with them, consoled and laughed with them. How could I not become personally entangled in their lives? Although few of the poems refer to specific people (you know who you are), all of them are shadows or ghosts of people I have known on some level.

3:AM: This personal and autobiographical element has an uncanny effect on your presentation of the nation at large. The intimacy crosses over, until the unimaginable is encompassed: China becomes a microcosm. It feels strange even to say that.

MV: Absolutely. I have come to see this ultra-rapid, development of the Chinese nation from a country of emperors and robber barons, through Mao’s Cultural Revolution, to its present “economic coming of age” as a metaphor for the development of modern “civilization.” In many ways what China has survived in the last forty years is much akin to Europe’s Industrial Revolution of the mid-Nineteenth Century. And despite the fact that much of the western world believes China is on a narrow path to taking over the global economy, one must bear in mind that eighty percent of China’s population still lives in abject poverty. The money and power remains in the hands of the few — most of them well intertwined in the CCP, the Chinese Communist Party — China’s modern emperors and warlords.

3:AM: One is put in mind of your Revolutionary Commander, merciful and jocular, who addresses his troops in the penultimate poem of section one.

MV: Right. In China today, you experience the greatest extremes of wealth and poverty, injustice and indifference. For me, Mao’s Mole is not just about China’s recent history, but about how time and again, myth is being reinvented to serve the purposes of the powers-that-be under the guise of modernizing a nation.

3:AM: Excellent. How about ending this interview with a sample from Mao’s Mole?

MV: Sure, Tom. Here’s an excerpt from “Why Yang Wants to Leave Wolf Mountain”

(2)

And Yang and I become the double-entendre of all Wu county,

that staccato at the end of a Peking opera played on fields of barley—

an embarrassment for those with no faith, but a miraculous creation

for those who worship the salacious Buddha with the pot belly

like faithful Grandpa Ye who Mother says is incorrigible.

Evenings when he sips dragon brew from his chipped red cup

he chortles in our ears—in those days we have only one little Red Book—

but he sits there plunked on the edge of our bed, stomping

to scare off night mice, to ease us into our dreams with ancient tales

of villagers passing through winter’s cold fingers, of fading

into the soft-snow of god-sky, only to remerge

as black-necked cranes under our mountain’s early haze.

(3)

Grandpa Ye claims he knows each crane by name,

every unique swell and swagger, each bellow and grunt;

who flutters brazen like Great Auntie Ma or sways

on one leg like Great-grandmother Shie, and he jests

that Uncle Fu always gobbled too many fried dumplings,

croaked & ruffled his wings in a huff, but just like any crane,

deeply admired the round paleness of our spring moon

over Wolf Mountain; perhaps because it reminded him

of the crisp butter pancakes Auntie Ma would roast

on freezing winter nights, stuffed with scallions,

raisins and that secret recipe of hers for sticky brown rice. - Tom Bradley

Today I bring you The Next Big Thing from Marc Vincenz and Bill Yarrow. Marc and Bill originally posted these interviews on Facebook a few days ago. Now, in this Write, Juggle, Run exclusive, Marc and Bill re-share their interviews for the world to see.

Marc: And here we go…avec un verre du vin: in this case, a bottle of Luis Felipe Edwards from somewhere “terraced” in Chile called the Cholchagua Valley. Apparently there are herds of genetically manipulated bovines dangling amongst the grapes over there.

Le fabulous Yahia Lababidi tagged me to take part in The Next Big Thing, a series of self-interviews with poets and writers (are they the same?) which perpetrates some kind of network writer’s marketing viral infection – something I’m personally not immune to.

It works like some form of reality TV / author-self-introspection, which earnestly speaking, is not what I’m about – except for in a self-glorification, self-promotional sense. Ergo: please read books – mine or anyone else’s. Enrich the flora, enrich the mind.

Through a series of interviews rather than by association something irrational occurs and people actually start purchasing books – either that, or we’re all mildly amused by this self-glorification act.

Bill: Marc Vincenz tagged me to take part in The Next Big Thing, a series of self-interviews in which poets and writers are all asked the same nine questions. (I’ve taken the liberty to rewrite the questions to make them grammatical.)

What is the title of your book?

Marc: Mao’s Mole.

Bill: Pointed Sentences.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

Marc: The idea – or fruition – of the book came from living over ten years in China, having been born in Hong Kong during Mao’s Cultural Revolution; in essence, a distillation of any and everything that I had experienced in and with China through something like forty years of life – real or imagined.

Bill: From under the floorboards. [translation by Constance Garnett.]

What genre is your book?

Marc: Poetry, sort of. Narrative, imagined, persona and re-lived – with a bit of extra modernist “zing” thrown in to the mix.

Bill: The first one.

If your book was made into a movie, what actors would you choose to play the part of your characters?

Marc: Ah. If Yul Brynner were still alive, he should be the lead role: the revolutionary outsider continuously trying to adapt to his circumstances – with failed consequences; someone like the character he played in the The Brothers Karamazov – a kind of James Dean of the Russian Revolution. Mao would most certainly be played by Peter Sellers, as would the Empress Dowager and a minimum of five characters in the book. Terry Gilliam would have directed the movie version.

Bill: Lya de Putti, Maria Falconetti, Vera Baranovskaya, and Jerry Mathers as “the Beaver.”

What is a one-sentence synopsis of your book?

Marc: We are all but microbes in the palm of a giant.

Bill: “the mind as Ixion” (Pound, Canto CXIII)

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

Marc: Four or five years.

Bill: How long did it not take?

Who or what inspired the writing of your book?

Marc: China, the world. Conformity. The modern, brand-absorbed world we live in. Myths and mythology. Ten plus years living in China; forty plus years experiencing China from a distance or close up.

Bill: The smashing of my windshield by a flying wrench.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

Marc: Honestly speaking although the over-arching fascination appears to be with China and its modern history, this book is about how icons come about; about how mythology is created, about how modern life is lived. Mao’s Mole is your mole – even though you may not yet know it. This book is about how an icon, becomes a mole, becomes a logo.

Bill: It’s written in “gangnam” style.

Who published or will publish your book? - Nathaniel Tower

excerpt

This book starts out listening for bees, and hears none, the listener being something of a pupa in a cocoon on the early pages. Honeycombs begin not as sources of Swiftian sweetness and light, but sloughs of despond. Honeybees themselves, initially silent, burn like fire at the stake. The hive is the shadow of death, full of sand fleas that stand in for the desiderated insects, along with "scrubitch" mites, Hercules caterpillars and flies: electro-kinetic pellets flecking / blank walls. The planet and its atmosphere, thus un-beed, become a single organism whose surface swarms with flotsam, jetsam and scabs reincarnating as silverfish. Earth's innards comprise more non-beehives that pullulate instead with arachnids and microbes and single cells that Vincenz eventually nurtures to dinosaurhood. We get former human cultures who made hive-like arrangements: ...the Cucuteni-who incinerated their own homes before wandering on...Bajau Laut tribes of Semporna who built their homes on coral reefs in the ocean. And that settled ocean, as always in Vincenz, is near. It's the opposed cosmos, again not a social insect world, but buzzing with fish, not in shoals, not in pods, but singularly alone like us. However, complete solitude is not our lot, because the seashore is inhabited by a remarkable figure: beachcombing Ivan in his ragged rope belt. He recurs throughout Becoming the Sound of Bees, making sense, or nonsense, of everything: screaming blue at the sea, braving the heavy metals of that other social creature, the bedded oyster, his eyes watering as he surveys the city's polluted human hive. This new book by Marc Vincenz, through sheer dint of numberless invention, hums louder and more beautifully than any of our world's collapsing colonies. - Tom Bradley

In the search for illumination, navigational lines transmute to brinks, horizons, loss; leaving the visionary to his intentional muse, a specific, dream-keen concise dead-reckoning splitting some supreme immortal blur. Here, Vincenz graces poetic bounty with waving rhythm, stirs a ruffling of ocean into sheets spread between man and more, giving us our own mortal reflection and calling us to sail. Becoming the Sound of Bees masterfully portrays the quest for truth in a journey ripe with the child-scrawl of angels, winged-spiders, honeyguides and honeybirds traversing the globe to locate home, and in this voyage brings a hero’s heart. Exemplary– Allison Adelle Hedge Coke

What a startlingly powerful collection this is. Vincenz’s Becoming the Sound of Bees, takes the reader to that vibratory level where narrative and the resonant energy of language are in continuous transformation. We are moved through veil after veil of the mundane then in and out of the tarnished glimmer of what might be otherworldly. The feminine figurations of oceans, daughters, wives are raved at by the iconic masculine prototype Ivan who dares “to scream Blue at the sea.” Frail universes build, crest, and capsize. Yet we are given exacting details from myth, history, science, and anthropology that fly by us humming, only to sink and collide seemingly in the same breath. The musical quality of Vincenz’s gorgeous language is remarkable; the narrative of a ruined earth is urgent. Yet always there appears a lucid gem of what might be (or once was), and it is in this “becoming” we discover a redeeming focus on singularity. The poem “The Sign, The Symbol, The Bird” offers such visual vigor in the flight of a simple thrush: “that flash of speckled feather resting at intervals on threadbare scrub,” only to “whistle back into her own marvelous concoction.” This collection is captivating both for its unique use of language and for the breadth, depth, and clarity of the narrative.—Katherine Soniat

Becoming the Sound of Bees is the music, the mind and muscle of a poet intimately engaged with the world becoming, with Being taking shape and presence. It is a fractured cinematic narrative where scenes saturate one another and characters shift and exchange faces, some of which are our own—such is the strength of its hold on the imagination. It is history (personal and communal) through kaleidoscopic mind, keenly aware that any event might open an unexpected portal into any other. It is trans-figuration out of the body toward infinite forms more real than symbols, more tangible than myth, yet ripe with the plenitude of both those modes. It is a book of physical knowledge as reveled by a natural philosopher in the ancient sense and a magician in the modern sense. It may be read as a collection of poems, but beneath that appearance lies a continuum, a singer sounding the depths and making finely articulated open verse out of the torrent of experience.

In Becoming the Sound of Bees, Marc Vincenz’s “facts of mind made manifest / in a fiction of matter” capture the process of transformation as it occurs in daily life, personal reflection and philosophical ideation. His sharp eye and deft hand capture shifts of perception that apprehend experience through language or as a manifestation of language itself. Provocative, beautiful, unsettling and highly recommended.—Vernon Frazer

Persuasive, pensive and experimental, in the best sense of that overused term, the poems in Becoming the Sound of Bees engage with a world that only seems as if it is failing us. In the appropriately titled, “Continuum,” Vincenz says “that a creator may/draw strings and each and every/last one may last/beyond the great oblivion/at the end of all things.” Other poems are entitled, “Yet Another Reincarnation,” “Godwilling,” and “After the Greatest War.” Through static, storms, panic and cacophony, Vincenz's poems emerge with a rhythmic, assonant, euphonious song that just might be a path toward salvation. This is a book of hope and vision that is uncommon because it is hard-won and true. Thanks are due Marc Vincenz for his clear-eyed farsightedness.—Corey Mesler

Within an expanding and contracting poetry—the mystical Ivan, scrapping fisherman or sea satyr, wonders amid the language of loss and despair and an ever-warring hope-- “...behind the walls a million oracles waiting.” – A mystical unraveling and unveiling – “..billowing into an oven of gold, or the unrelenting hands of anti-matter...” – Vincenz’s poetry evokes worlds of detail anchored through figures of power and perpetual demise who are most humble and common, wise and dangerous—and capable of a Dostoevskyisan consciousness and suffering. Rather than a poetry of anger and retaliation, Vincenz’s poetry trawls the realms of existential crises, hope and possible redemption—but only within a purview of this nature’s passionately quotidian terms.—George J. Farrah

One might think that Becoming the Sound of Bees would entail mixing with the white noise of the natural world and miss the specific symmetries and orchestral richness of that world's hidden, vital communications. Since bees are the landscape architects of the American pastoral story, their purpose is intrinsic to our planet's survival. Vincenz slowly unravels all the grace notes of this necessary mission with his own unfailing music and pollinates the reader's imagination with a host of metaphorical associations. His narratives illustrate the impossible odds of true human interaction and shows us how poetry can provide the improbable solutions inside the human hive, where all bets are off. In the lava roll of his imagination, Vincenz’s poems uncover the tender places where we might reconnect. In a variety of shapes and rhythms, he makes of this book a balm that heals the wounds we inflict upon one another, and the natural world, by virtue of all our appetites and reasons. This book is a powerful reminder of just why poetry is what the world really wants when its heart is broken —Keith Flynn

Reading Marc Vincenz’s Becoming the Sound of Bees is like scrying the future, grim and close at hand, on the surface of a poisoned sea. The world conjured here dies variously: empty after the sweep of epidemic, swallowed up by natural disaster, nations crumbling and reduced to their smallest plastic parts. The message feels familiar, as if we have been cast out of Eden all over again, except this time we are not granted dominion over the beasts of the field. Instead, we are unseated by even the smallest creatures, and minding Vincenz’s nod to Louis Pasteur’s developments in germ theory, the human race once again falls prey to forces undiscernible to the eye. Though the question remains why today, despite our enhanced vision in the field of science, we continue to disregard the smog above the cityscape, the paper-thin ruins of abandoned hives.

Vincenz’s collection seems endlessly interested in the act of seeing—what signals come from the world around us and which of these we grant our attention. The poems here remind us of how mythologies of past civilizations, given their imperfect knowledge of the universe, offered only a fragmented picture of existence. But believing the Earth rests upon the backs of turtles or that one might die only to live again in the body of a moth doesn’t seem nearly as foolish as ignoring the seas filled with bottle caps and aluminum cans. This collection calls out for a renewed worship of a neglected world, depicting characters desperate to make an oracle of a dying planet, to search madly for a strand of hope.

Vincenz’s “Ivan,” as flawed and earnest as Hughes’ “Crow,” alone scavenges a post-apocalyptic seashore for remnants of an otherwise forgotten human history. Again and again, the soft flesh of his hands comes up against the armored bodies of sea creatures and sharp spines washed in by the tide. The speaker in these poems seems to commune with Ivan in his bleak existence, and it is unclear if they are not two voices split in the same mind. They are only further connected in “Pull of the Gravitons,” in which the speaker ingests Ivan’s blood as one might partake of the sacrament:

Ivan hands me the oyster in his bleeding fingers and I eat it

tasting the distinct flavors of iron & magnesium & reducible elements

like the ocher I wipe with the back of my hand.

Our past is another now, I say, closing the curtains.

Vincenz invites us to recognize ourselves in Ivan, someone left with the sins of the entire human race in his hands who cannot possibly hope to redeem them. This pseudo-sacrament once again reminds us that we are nothing more than the smallest components of our world—there is no divinity that will swoop from above and deliver us from evil. The time for that has passed. It would have happened by now.

It is difficult not to regard Becoming the Sound of Bees with reverence as it leaves one hushed and listening for humming over the hills. Vincenz’s collection worships even the tiniest creatures and encourages us to align ourselves with them, to open our eyes and to share our bodies. It is through this thoughtful reckoning with our world that we avoid the desolate future Vincenz’s oracle reveals. This collection asks that we reexamine what we’ve placed upon our pedestals, what at any moment might crumble, what sort of legacy we will leave behind. We must mind these words as we would a prophecy: “it’s better to live again transmorphed even if only/as a moth flickering as a bat-bait changeling inspiration for gods’ wings…” - Amanda Mitchell

we listened

for the sound of bees

& hearing nothing

but the wind boxing the panes

we began to hum & buzz & drone

becoming the grey matter

before words

An amalgam of mythopoetic fragments woven into a narrative thread, Becoming the Sound of Bees assembles time in a triage of moments via the life of a shell-shocked wayfarer named Ivan. The individual poems here are integral parts comprising a narrated synergy that strives to recombine and recover Ivan’s personal gestalt: “It is a fractured cinematic narrative where scenes saturate one another and characters shift and exchange faces, some of which are our own” (Jake Berry).

Ivan is the Everyman, even as he is a protagonist with no heroics attached. The Everyman character in the text is shadowed by the narrator/commentator, allowing us to break through the fourth wall, that semi-porous membrane that covers our shared meldings with Ivan. The voice is omnipresent in this story, which also allows us as readers to project ourselves into Ivan’s wounded core; into the evocative imagery of these beach scenes; and most certainly, into his process of transmorphing himself while he uses his pain as the fuel to keep going in this shattered world of his.

We too are mythology … to live again transmorphed.

One wonders if Ivan might be a former academic, one who has experienced some form of life-shattering breakdown. Has he lost a child named Max? Has his wife also died? Or both, through some vicissitude of fate? He apparently no longer makes sense as he wanders through the dystopian scapes of his life on the beach, acquiring the detritus offered up by the oceanic tides. His prowess in the art of beachcombing, however, is immense and all-consuming.

Living in a ramshackle bivouac above a slough, composed and held together by civilization’s washed up debris, his is a cobbled-together beachcomber’s shack where he boils seawater for stews of invertebrates and kelp. He has chosen this spot on the bluff above the beach for access to the tides and what gets brought forth nightly. In a parallel way, his own personal tide coalesces with the oceanic tide, that giver of flotsam, existential knickknacks, and ephemeral trash.

Ivan, King of the Seaweeds, this exile from civilization, has become a bottle cap hoarder, nailing them to the south wall of his shack with any rusty sharp thing he can find. “Twist the Cap” has become his mantra. He is Ivan the Geomancer, pursuing auguries through this mythopoetic journey by the sea, drinking a psychotropic broth from a plastic bucket, which sources his hallucinatory episodes while a grey thrush chirps out fresh bird language as Ivan mimics its song. He and his commentator traipse up and down the beach, observing “the curious cacti on the hills,” Ivan soldiering his way on through his presumed PTSD hours, stumbling forth like one of Cormac McCarthy’s traumatized characters. Malcolm Lowry, another famous beachcomber, who sheltered up in a seaside bivouac in British Columbia, exiled from a world too wounding to live in, also comes to mind here.

Yet, given all this, we still want to know who this Ivan really is, this hoarder of memories, akin to Beckett’s Molloy perhaps, that outcast who hoards his sucking stones in a lonely sea cave. Ivan the beachcomber, with a loose rope belt such that he has to keep hitching up his odoriferous threadbare trousers, screams “blue at the sea” -- “I’m the You!” he yells as he angles with his makeshift spear. He is a recorder of “illusions and smoke-knowledge,” indicating that “smoke is our umbilical cord … to the dark deities.” Perhaps through his scribbled metaphors, a possible redemption/salvation is being generated while he traipses across the silent desolate sands.

Also, referencing any possible absence of bees, apparently it is now us doing the buzzing. Yet how do we become, or even incorporate, the sound of the bees? Especially the buzzing sound, as defined in the word bombinate: to rumble, buzz, hum, or produce a low boom. The continuous sound of the surf that Ivan absorbs with each daily cycle may echo the symbolic sound of the bombination of bees. Or internally, there is the systole/diastole oscillation of this pulsing life, the sound of the blood as it expands and contracts through his cranium. Through this process of transmorphing that Vincenz alludes to throughout this text, perhaps this gives us a clue about the imminent peril that we as residents of earth now find ourselves in.

While in the pregnant silences heard at noon, that is the noon that until recently was endowed with the low hum of apian industry, this quiet may fill the entirety of our empty days ahead. And yet this narrative, as loaded as it is with the metaphorical associations of hope, warns us about more than the demise of bees. Through poetic language that goes kaleidoscopic in Becoming The Sound Of Bees, we are given a sketch of what our future might become, whether we choose to heed it or not.

Certainly the exuberant forces exhibited by Vincenz’s imagination, erupting forth like Pele’s magma flowing into the Hawaiian seas, is palpably apparent in these poems, an igneous fluidity that depicts a human tragedy through the existential aftermath of coping with traumatic loss. One thinks of Berryman’s Henry, another soul who has suffered an irreversible loss like Ivan, proceeding through the minefields of self-alienation and depression.

As one reads through these poems, it is striking how Vincenz has this great gift for working his language into such evocative imagery, his penchant for the scholarly blending with the quotidian, driving the transformative thematics throughout these poems. This book serves to remind us that breakdowns in our consciousness can also serve as breakthroughs; we will prevail only with the integrity of our fellow apian creatures if we do not succumb to despair, and proceed with hope and desire towards interpersonal wholeness. - Matt Hill

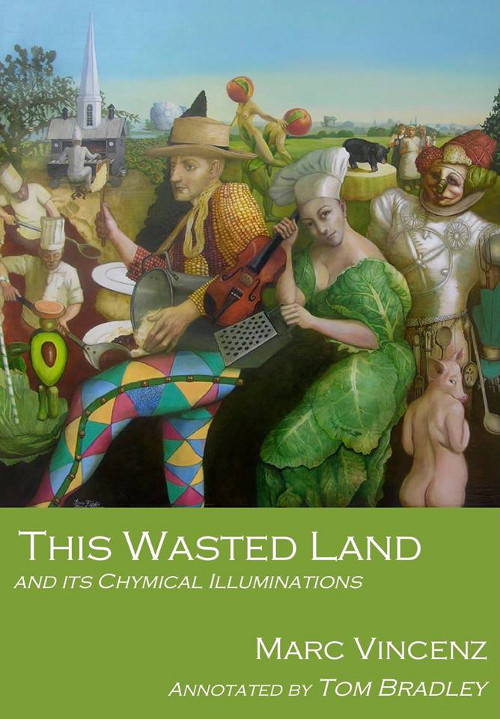

Marc Vincenz, This Wasted Land: and Its Chymical Illuminations, Lavender Ink, 2015.

Marc Vincenz has achieved the virtuosic feat of rendering homage to The Waste Land while simultaneously engendering a love epic of nine hundred lines. Vincenz enters and plunders the minds of Alexandrian gnostics, Celtic Druids, medieval alchemists, magi if the Iranian Plateau, and tantric adepts of the Indus Valley.

Meanwhile, Tom Bradley has annotated this book in the strange way he did Epigonesia and Felicia's Nose. He strip-mines the pseudepigrapha and snuffles into Mariolatry's odd pastel nooks, where the sense of smell prevails over all others. As a precaution, Bradley doesn't neglect to conjure the crone initiatrix of the Vama Marga who teaches prophets, seers and revelators to control their gag reflex. Gradually, something like a novel materializes among the endnotes. A strange figure emerges: Siegfried Tolliot, who, in 1958, shared intimacy with Ezra Pound at Saint Elizabeth's insane asylum in Washington, D. C.

The result is that rarity of rarities: a new genre, situated in real time as the poet's bright lyricism contends with the cackling paranoia of his annotator. It all culminates in a 300-item bibliography and an index of 900 entries, citing everyone from Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa to Zosimos of Panopolis.

Nothing like it. A transcendence. Completely novel. Will be remembered forever. And that is an understatement. I didn't think giants still walked the earth. I know about comedy, wit, multiple allusions... but I didn't think anyone was still around who could do what Vincenz and Bradley did in This Wasted Land... delight after delight...—Joe Green

A palatial homage to Eliot; ludic cruise through Pound's errata. Ideally epic, This Wasted Land preens and pummels conceptual imagery into a sacred profane realization of feminine figure manifesting appearances in a spindle of eras. The letter leaves no wand unwaved, no veil unraised, no, the fearless love song curiously transfigures her extreme essences throughout time. This is transnational and transcontinental muse. A meditative investigation with rare sourcing, scat. Instead of the traditional, Vincenz rips it up with careening force, rhythmic gales unleashing the unexpected. Freely loosening rodents, pestilence, while he borrows the familiar beautiful, iconic then couples comfort with foul, casts off ashen and machinated debris, all the while experimenting his way through encoded episodic verse, gaining poetic perversity in annotated wanderlust, and topsy turvy embrace. This isn't the love song we thought we came for—it's the chase. Bradley's multilayered, alchemical annotations, anchor this book—the poem, the notes, the expansive bibliography – deliver a rare multiverse of a read. Phenomenal, scintillating.—Allison Hedge Coke

From 'the dimness of that Portobello antique shop' to 'purple-haired Cornish coach tourists', from 'laminated tabletops and the mountain ranges beyond Chengdu' to 'those gondalieri, wild ones with their coppery manes', Marc Vincenz conjures, with ostensible effortlessness, memories one is aghast to realize one scarcely knew were there, rather in the manner (however unlikely the comparison) of Somerset Maugham's The Moon and Sixpence. Playful but pensive incongruities—a 'judicial right of crenellation', the flick of a stub to the floor, 'disgusted at the lack of ashtrays'—do that rare thing of poetry responsibly riddling the reader. Tom Bradley's copious and critical annotations give us the capricious erudition of a T. S. Eliot in March Hare guise, whilst delivering such mirthfulness as would befit Boccaccio. In Vincenz's own words, 'the mind reels, tied to a mast, the heart burns, roped up.'—Umit Singh Dhuga

“And Ezra Pound and T. S. EliotFighting in the captain’s towerWhile calypso singers laugh at theAnd fishermen hold flowers”

Desolation Row ~ Bob Dylan 1965

A trenchant shot across Tom Bradley’s bow from the mysterious Siegfried Tolliot:

I suspect such peccadillos are not all that have kept him out from behind the professional podium. Displaying what can only be described as flippant disregard for intellectual rigor, Bradley has sunk alongside T. S. Eliot into “remarkable expositions of bogus scholarship.” He indulges in deliberate non-sequitur, which he no doubt dignifies as “impressionistic analysis.”

And some sardonic scholarship from Tom Bradley regarding Siegfried Tolliot:

Tolliot showed up in the “schizy ward” on the rounded heels of the author of Howl after the latter had orally primed old native Idahoan … the priapic eunuch put himself into position to lend Ezra Pound a carton of Kool mentholated cigarettes …

The book is a multilayered opus of brilliant prose, lyrical poetry, erudite scholarship, high culture, low culture, acerbic wit, droll humor, high parody and satirical exchanges between the author, the annotator, and the mysterious Siegfried Tolliot. This Wasted Land is a hybrid of ekphrastic parody, tribute and scholarly research. To be honest, my initial encounter with the book left me confused and befuddled. In fact, I wasn’t sure what was a put-on and what was actually serious. There are mysterious passages in German and French and a dizzying array of far-reaching annotations that include links to the Rosicrucians, the First Golden Age, alchemy, the occult, magick, the Annunaki, the Nephilim, and enough other esoteric references for a PhD dissertation. There’s even a disambiguation of the musician Manfred Mann and his classic hit from the sixties British Invasion, “Doo Wah Diddy Diddy.” The old country song by Skeeter Davis, “I Forgot More Than You’ll Ever Know,” came to mind as I remembered so many historical references that had been relegated to the dustbin of my own liberal arts education. If you are willing to dive headfirst into this grand literary smorgasbord and pay close attention, you will emerge with an updated education in classical humanities. Here is an example of some of Vincenz’s gorgeous lyrical poetry:

blue heaven begins to hum a far less wretched tune

of rain and chymical sorcery, coercing tubers and roots

to squirm within sallow layers—and serpents twisting

beyond the line of sight; thawing toads seek beguiling light,

yes, even millipedes tapping into steady locomotion.