Marian Engel, Bear, 1976.

The winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction, Marian Engel’s most famous – and most controversial – novel tells the unforgettable story of a woman transformed by a primal, erotic relationship. Lou is a lonely librarian who spends her days in the dusty archives of the Historical Institute. When an unusual field assignment comes her way, she jumps at the chance to travel to a remote island in northern Ontario, where she will spend the summer cataloguing a library that belonged to an eccentric nineteenth-century colonel. Eager to investigate the estate’s curious history, she is shocked to discover that the island has one other inhabitant: a bear. Lou’s imagination is soon overtaken by the island’s past occupants, whose deep fascination with bears gradually becomes her own. Irresistibly, Lou is led along a path of emotional and sexual self-awakening, as she explores the limits of her own animal nature. What she discovers will change her life forever. As provocative and powerful now as when it was first published. Includes a reading group guide.

Marian Engel, who died in 1985 after a tragic struggle with cancer, was among Canada’s most celebrated and beloved novelists. Her last, best known, and most controversial book was Bear (winner of the Governor-General’s Award) in which a mousy, timid librarian is summoned to a remote Canadian island to inventory the estate of Colonel Cary, who, she learns soon enough, had any number of secrets. But the most surprising and enduring secret is a pet bear. In thirty pages, the reticent librarian meets the not so reticent bear and “wonders if it would be good company.” It is good company indeed. Intimate company. Shocking company.

This book contains mature content.

Bear is a strange and wonderful book, plausible as kitchens, but shapely as a folktale, and with the same disturbing resonance. — Margaret Atwood

Excerpt:

In the winter, she lived like a mole, buried deep in her office, digging among maps and manuscripts. She lived close to her work and shopped on the way between her apartment and the Institute, scurrying hastily through the tube of winter from refuge to refuge, wasting no time. She did not like cold air on her skin. Her basement room at the Institute was close to the steam pipes and protectively lined with books, wooden filing cabinets and very old, brown, framed photographs of unlikely people: General Booth and somebody's Grandma Town, France from the air in 1915, groups of athletes and sappers; things people brought her because she would not throw them out, because it was her job to keep them. "Don't throw it out," people said. "Lug it all down to the Historical Institute. They might want it. He might have been more of a somebody than we thought, even if he did drink." So she had retrieved from their generosity a Christmas card from the trenches with a celluloid boot on it, a parchment poem to Chingacousy Township graced with a wreath of human hair, a signed photograph of the founder of a seed company long ago absorbed by a competitor. Trivia which she used to remind herself that long ago the outside world had existed, that there was more to today than yesterday with its yellowing paper and browning ink and maps that tended to shatter when they were unfolded. Yet, when the weather turned and the sun filtered into even her basement windows, when the sunbeams were laden with spring dust and the old tin ashtrays began to stink of a winter of nicotine and contemplation, the flaws in her plodding private world were made public, even to her, for although she loved old shabby things, things that had already been loved and suffered, objects with a past, when she saw that her arms were slug- pale and her fingerprints grained with old, old ink, that the detritus with which she bedizened her bulletin boards was curled and valueless, when she found that her eyes would no longer focus in the light, she was always ashamed, for the image of the Good Life long ago stamped on her soul was quite different from this, and she suffered in contrast. This year, however, she was due to escape the shaming moment of realization. The mole would not be forced to admit that it had been intended for an antelope. The Director found her among her files and rolled maps and, standing solemnly under a row of family portraits donated to the Institute on the grounds that it would be impious to hang them, as was then fashionable, in the bathroom, announced that the Cary estate had at last been settled in favour of the Institute. He looked at her, she looked at him: it had happened. For once, instead of Sunday school attendance certificates, old emigration documents, envelopes of unidentified farmers' Sunday photographs and withered love letters, something of real value had been left them. "You'd better get packing, Lou," he said, "and go up and do a job on it. The change will do you good."

Much has been made of this book--it's sponsored by all the right people in Canada where it's set--Margaret Laurence, Robertson Davies, and Margaret Atwood. Much can be made of it on several plateaus of time and existence and reality, from mythic to very modern, primal to civilized. Within its 150 pages, it encloses strong feminist protest against the domestication of of woman, interior evidence of the personal increment rather than impoverishment of solitude, and--in case you startle easily--a passionate relationship between a woman and an animal which is wholly believable and unobjectionable. Lou is a hibernator by nature, commuting between her apartment and the Institute where she does research. She has no personal contacts except for on-the-desk carnal congress with its Director once a week. Now he sends her to a lonely island further north where the Institute has inherited an estate. She is to research its books and belongings which include a bear, on a chain--a rather ugly bear with small eyes and a randy scent. But he has virtues along with legendary associations--the bear was believed to have ""the strength of ten men, and the sense of twelve."" Lou takes him off his chain and then enters into an at first friendly, later erotic (bear licks her all over even if he doesn't respond until the close) community with this tender, wise, gentle, undemanding, lumbering animal who proves to be so lovable. At the end of the summer they will go their separate ways. Lou locks the door on her whole past and leaves on ""a brilliant night, all star-shine, and overhead the Great Bear and his thirty-seven thousand virgins kept her company."" A special book which persuades and reaches the reader in many ways--a timeless book written with a cool, classic touch.- Kirkus Review

Much has been made of this book--it's sponsored by all the right people in Canada where it's set--Margaret Laurence, Robertson Davies, and Margaret Atwood. Much can be made of it on several plateaus of time and existence and reality, from mythic to very modern, primal to civilized. Within its 150 pages, it encloses strong feminist protest against the domestication of of woman, interior evidence of the personal increment rather than impoverishment of solitude, and--in case you startle easily--a passionate relationship between a woman and an animal which is wholly believable and unobjectionable. Lou is a hibernator by nature, commuting between her apartment and the Institute where she does research. She has no personal contacts except for on-the-desk carnal congress with its Director once a week. Now he sends her to a lonely island further north where the Institute has inherited an estate. She is to research its books and belongings which include a bear, on a chain--a rather ugly bear with small eyes and a randy scent. But he has virtues along with legendary associations--the bear was believed to have ""the strength of ten men, and the sense of twelve."" Lou takes him off his chain and then enters into an at first friendly, later erotic (bear licks her all over even if he doesn't respond until the close) community with this tender, wise, gentle, undemanding, lumbering animal who proves to be so lovable. At the end of the summer they will go their separate ways. Lou locks the door on her whole past and leaves on ""a brilliant night, all star-shine, and overhead the Great Bear and his thirty-seven thousand virgins kept her company."" A special book which persuades and reaches the reader in many ways--a timeless book written with a cool, classic touch.- Kirkus Review

Canadiana is a funny and ridiculous thing — maple syrup tins, wooden hockey sticks, Mountie hats, golden-era NFB and CBC logos developed in the socialist ’70s, when the national dream was still so vivid; while Americans have apple pie, we have … I don’t know, roll up the rim? Ours is not a cosmopolitan nostalgia.

Let me be clear: I grew up in a city, and I live in one now, but I’ve hiked in the Rockies and seen the Northern lights. I’ve tasted Ontario’s peaches and Montreal’s bagels, and I’ve felt the mist on my face in New Brunswick. I was even in an intramural ball hockey league as a fumbling adolescent. But for the most part, artifacts of Canadiana tend to leave me colder than Fort Mac in January.

But then there is 1976’s Bear, newly reissued this month. Earlier this year, a few passages from the Canadian literary classic found their way onto Imgur, a social photo-hosting service. The short excerpts of Marian Engel’s most well-known novel were viewed millions of times. The passages described a woman coercing a literal bear into a sex act.

What you can’t tell from the short (and furry) erotic passages posted to the Internet is that Bear is a damn good book; in fact, it is the best Canadian novel of all time.Funny and sweet, Engel’s 1976 Governor General’s Award winning (more on that later!) erotic novella follows Lou, a bookish 27-year-old woman employed by a pseudo government agency called the Historical Institute out to a remote homestead in the Northern Ontario woods, where she spends time investigating dusty old books. If Bear were first published today, we’d bill it as a literary account of a woman’s quarter-life crisis; we’d say Lou’s journey of self-discovery is a heart-rending portrait of the difficulty of maintaining a work-life balance. We’d congratulate Engel for crafting such a profoundly relatable protagonist, in an era where work takes over more and more of our lives and the traditional markers of maturity (marriage, home ownership, pension plans, legitimate weekends) are being lost on the rocky terrain of an increasingly precarious contract-term economy.

(I’m not sure, if the novel were first published today, that Lou would still fellate an actual bear, or that it would win the GG, but one can hope.)

The reason Bear is the greatest Canadian novel of all time is not because I, a 27-year-old woman with a piss poor sense of the boundaries between work and life, found it relatable. Bear is great because of what it manages to do through language in its meagre 115 pages. Engel’s prose turns swiftly from the comic to lyric and back again — here she is being funny as hell, describing her protagonist’s mounting frustration with her official task, and cracking at everything en vogue in ’70s literature: “She felt like some French novelist who, having discarded plot and character, was left to build an abstract structure, and was too tradition-bound to do so.”

Engle’s comic range is broader than metafictional jabs: at one point, after licking Lou to the brink of orgasm, the bear (who is never once anthropomorphized) actually walks away from her, still in the glow of passion, trailing bear farts behind him.

I don’t want to spoil anything for you, or at least not more than I already have, but the thing about Bear is how trivial the actual bestial fornication is in the grander scheme of the novel — Lou is a contemporary woman, making her way in a world that wasn’t built for her. Sitting beneath the portrait of the Colonel, depicted in regalia, whose library she is cataloguing for the Institute, Lou, a military biography in her lap, extends her feet out into the fur of her animal lover, and feels “exquisitely happy,” because “a woman rubbing her foot in the thick black pelt of a bear was more than they could have imagined. More, too, than a military victory: splendour.”

Studying some dead rich guy, staying in his historic family house, trying to parse together his military connections to the region so that she can best preserve some arbitrary record, Lou observes that the “Canadian tradition was, she had found, on the whole, genteel.”

And in part for its extravagant strangeness, for the disruption it poses to that staid, woollen mitten of a tradition, Bear deserves to be celebrated. And yet. The niftiest trick Engel pulls is to simultaneously disrupt and continue that tradition — a perfect sublimation of the tensions of working to advance a living art form in a country with a hard on for the past. - Emily M. Keeler

Bear is essentially a (transforming) summer-in-the-life novel. Canadian librarian Lou works at the Historical Institute, and when the legal wranglings about the disposition of an estate are finally over she is charged with assessing what exactly the Institute has inherited, and how it might be utilized. A Colonel Jocelyn Cary had left an estate, Pennarth, on Cary's Island, to the Institute, and it was said to contain: "a large library of materials relevant to early settlement in the area".

Lou packs her things and travels to the island in mid-May, to inspect and inventory the property, and she winds up staying through the entire summer (and rather longer than she strictly needs to). A local, Homer Campbell, is her contact person, familiar with the property and helpful with what she needs to get by -- including some supplies. Her home for the summer is both old-fashioned elegant and rustic, with neither central heating nor electricity. The library includes a few valuable pieces, but on the whole is relatively unexceptional. And there's also a bear, kept on a chain -- "It's there, and it belongs to the place", Homer explains. Yes: "There had always, it seemed, been a bear".

Lou likes her situation:

ithout giving up her work (which she loved), she was deposited in one of the great houses of the province, at the beginning of the summer season and in one of the great resort areas. She was somewhat isolated, but she had always loved her loneliness. And the idea of the bear struck her as joyfully Elizabethan and exotic.

The inheritance turns out to be a bit of a dud:

What the Institute needed was not a nice house, or a collection of zoological curiosa but material to fill in the history of settlement in the region.

There are odds and ends of historical and family interest that Lou uncovers along the way, but clearly all this isn't quite the boon the Institute had hoped for. Lou, however, enjoys her experiences, a mix of using her book- and historical-expertise and coping with a very different way of living -- even if she is unsuccessful in many ways, from her attempts at gardening to fishing.

And there is, of course, the bear. Approaching it warily at first, she quickly gets used to it, and it to her. She takes it off its chain, goes swimming with. And, yes, she gets more intimate with it. The pleasuring is mostly cunnilingual, but the bear knows what it's doing:

And like no human being she had ever known it persevered in her pleasure. When she came, she whimpered, and the bear licked away her tears.

The bear remains largely inscrutable, but that also allows Lou to make of it what she wants. The two very different creatures find comfort in physical proximity and, yes, Bear is a love story, of very odd sorts.

Bear is notorious for being about that -- woman has sex with a bear ! -- but really that is only one part and facet of what is a much richer novel. Not only is there more to it than the sex -- which itself is delicately and very well-handled -- but even just regarding Lou and the bear, it's the relationship that develops between the two -- cautious, halting, each remaining an enigma to the other -- that is far more interesting than just the sexual encounters. In making it what is essentially an impossible love -- and in portraying sex (in its broader senses -- one can hardly speak of any sort of simple 'sexual act' here) as the awkward, mystifying, lone experience it remains, regardless of partner -- Engel's presentation of carnality and human longing is exceptional.

Lou's summer-stay, with the changing seasons and the coming and then going of the tourist-crowds -- nearby, but only somewhat intruding -- makes for a convenient narrative arc. It is, to put it simply, a summer of self-discovery for Lou, and she departs as a changed and more fully fledged person; she grows, as a woman and an individual. And Engel's art is in the simple description that proves to have great depth, beautifully balanced between the mundane and naturalistic, and the (always believable) unusual.

This is a lovely piece of work -- and while the sensational premise is hard to overlook, the shorthand (bear-sex) by which everyone remembers the book, there really is considerably more to it. - M.A.Orthofer

Let’s lay it out as simply as possible: Marian Engel’s Bear is a novel about a woman who has an erotic relationship with a bear. As you can imagine, this is the sort of premise that probably makes book cover artists lick their lips with anticipation.

Last year, a screenshot of a Tumblr post about the cover for Bear appeared on the image-sharing site Imgur, and it went viral, with almost a million views. On Reddit and Facebook, people snickered at the cover, at its proud claims that Bear was a Canadian bestseller, and that it’s the winner of a Governor’s General Award, which, a poster assures us, is “the Pulitzer Prize of Canadian literature.” They call Bear a “Harlequin romance” — not at all true — and mock the book as though it’s a trashy romance novel for horny old maids.

Reddit user Kookiejar reviewed Bear soon after the Imgur post went viral. Perhaps “reviewed” is too strong a word; Kookiejar mostly offered a synopsis of the book leavened with intended-to-be-humorous commentary — “Is there enough bleach in the world to cleanse my brain from reading this?” — to assure the audience that s/he was maintaining an ironic distance from the text, and not enjoying it too much. There’s about one whole paragraph of actual reviewing in Kookiejar’s Reddit post, and here it is:

I think the author wanted this to be a feminist piece about how men are pretty much just like animals because you could have replaced the bear with a man at any point and not changed the jist of the book. In fact, the MOST uncomfortable (for the reader) sex scene happens between Lou and a human man. Unfortunately, the author failed to get this point across in any meaningful way and it ended up just being about a lady getting her crotch munched by a bear.

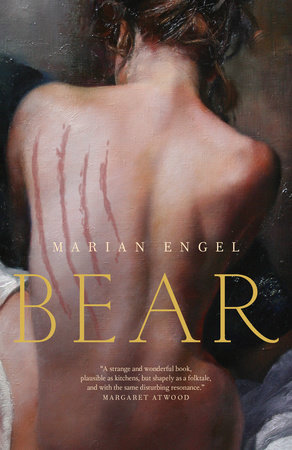

The book cover’s popularity inspired Penguin Random House to publish a new edition of Bear at the end of 2015. The new cover, credited to MaraLightFineArt.com, is to the left of this paragraph. We can see a woman’s naked back, with four ragged claw marks stretched across the right shoulder. She’s sitting, nude, on white sheets, and the rest of the room is obscured in a rich, dark, furry darkness. The image practically smells musky, like a bear, but there is no bear to be seen.

The new cover of Bear is a more austere image, one which plays into the more suggestive erotic covers of the modern age. Instead of thrusting hips or heaving bosoms, the flagship for the mass market erotic novel revival, the Fifty Shades of Grey trilogy, all feature inanimate objects — a necktie, a mask, a pair of handcuffs — photographed lovingly. It’s less porny, less male gaze-y, and more suggestive. Rather than brag of awards or use Canada as a punchline, the only other writing on the cover of Bear aside from the title and author is a wondrous blurb from Margaret Atwood, calling Bear as “plausible as kitchens, but shapely as a folktale.”

It’s easy to admire the 1976 cover for its brashness. The 2015 cover’s failure to include a bear feels like a cop-out, a sop to more “realistic” modern tastes. But there’s surely something to be said for letting the browser’s imagination do the storytelling; the human-on-bear sex happening in the private thoughts of a customer in a bookstore is undoubtedly more graphic than anything you could stick on the front of a paperback. As we’ll see, in this way it’s a better counterpart to the text.

Apparently, the rumor started when reviewer Roger Friedman wrote that “the bear flips Glass over on his belly and molests him – dry humps him actually – as he nearly devours him.” There is a moment in the bear attack sequence when Glass is crawling away from the bear on his belly, and the bear reaches out and grabs him and pulls him backwards toward it. It could, in the eyes of someone who is primed to see it that way, appear to be the beginning of a sexual assault. The scene isn’t an implied rape; it’s not really sexual at all.

The thing is, the internet seemed absolutely ready to believe the DiCaprio bear-rape story. On the morning that the Drudge link happened, Twitter began widely speculating about the scene. Collectively, the internet told itself: “That couldn’t be true.” But then the internet came back around and whispered to itself, “…could it?” Nobody had ever talked about The Revenant as much as they did in those 24 hours.

But why? Why are we fascinated with the sexuality of bears? Perhaps this is because bears, like gorillas and other large animals that can walk around on their hind legs, seem to us at moments like Humans in Furry Suits. But while most of us see gorillas behaving innocuously at zoos and in other docile settings — think Koko the gorilla telling a researcher in sign language how much she loves her pet kitten, which she named All-Ball—we are entirely petrified of bears.

And for good reason! Bears are terrifying. They roar and the parts of them that aren’t thick with fur are pointy and sharp. They’re heavy and they’re wild. And depending on the variety of bear doing the attacking, experts tell us in case of bear attack to either play dead or to run away. Even if we choose the correct survival plan for the correct type of bear (do we play dead when a black bear attacks, or do we play dead for a grizzly? Is running away from a grizzly bear fatal?) we might die anyway.

So we know that a bear’s anger is almost certain to be lethal. But what about its passion? There’s no better window to a human’s soul as that moment when they lose control, either through arousal or when they become entirely, irrationally angry. If a friend destroys objects or puts his fist through drywall when he loses his temper, that can be a scary moment of truth for people who thought they knew him. If a person behaves with intelligence and restraint even when they’re quivering with rage, our respect for them is likely to grow.

But we’re fascinated by that loss of control. We’re drawn to it. There’s a reason the English language is full of expressions like “I want to fuck you senseless” or “silly” or “stupid” or “like an animal.” The suggestion is that you have sex to get outside yourself, to tap into something rawer, more primal. In other words, to visit the place where bears live all day, every day. The symbolism of bear sexuality couldn’t be more obvious if you think about it: it’s a smelly, hairy, enormous stand-in for the loss of self.

Bear. There. Staring.

She stared back.

Everyone has once in his life to decide whether he is a Platonist or not, she thought. I am a woman sitting on a stoop eating bread and bacon. That is a bear. Not a toy bear, not a Pooh bear, not an airlines Koala bear. A real bear.

It’s not “Me Tarzan, you Jane,” but it’s pretty close. You can practically imagine the bear standing there facing her, sniffing the air and making the same assessments in the ursine folds of its brain: “woman. Bread. Bacon.”

But soon, the bear proves itself to not be a threat — Lou was warned of the bear in advance and assured of its gentle nature — and the two take stock of each other.

The bear stood in the open, on all fours, and stared at her, moving its head up, down, and sideways to get a full view of her. Its nose was more pointed than she had expected — years of corruption by teddy bears, she supposed — and its eyes were genuinely piggish and ugly. She crossed the yard and pumped it a pail of water.

It’s not very long, a handful of pages, before Lou is inviting the bear into the house, his “claws clacking on the kitchen linoleum.” Lou notes that indoors, “he looked very large indeed. At the top of the stairs, he drew himself up to his full height, in that posture that leads the bear to be compared to the man.” She identifies him as “a cross between a king and a woodchuck.”

The sexy stuff doesn’t happen until later. Bear is a story of seduction, and so there’s a deferment of pleasure. For a book that barely crosses 100 pages, there’s very little of the language turned over to description of the sexual contact. (I’ll not quote any of those passages here, because it seems unfair to the book to rob it of the thing that draws readers to it.) Lou gets to know the bear, takes it in, and then she starts to touch it and to observe it up close. And then things start to happen.

But the bear is not interchangeable with a human. This is not the furry version of The Bridges of Madison County, nor is it Fifty Shades of Grizzly. Lou is aware that she is committing bestiality, that she’s having sex with an animal. She suffers very little guilt for it, but she doesn’t try to convince herself otherwise, either, that she’s doing something noble, or unselfish. But this isn’t just a story of sexual liberation, or a tale of finding your savage side. There’s a real transgression, and that’s part of what makes Bear so successful as a story.

I also have to take issue with Kookiejar’s claims that the book is “a feminist piece about how men are pretty much just like animals.” Bear, in fact, is barely interested in men, except for the one who has a retractable bone in his penis. The human man who Lou does have sex with in the book doesn’t register as a character, except for some unpleasant personality traits that advance the plot a little bit. No, this is a story of a woman, by a woman. But maybe some men have a hard time thinking of women as people; maybe some men think of women as something alien to their own experience, as distant as bears are to people. Maybe that’s part of the point.

Ultimately, and unsurprisingly, Margaret Atwood is exactly right. Bear works best as a weird fable. But it’s not the kind of fable where the bear is a good-hearted prince in disguise. And it’s not the kind of story where a brave woman is punished for trying to reach outside her experience. Even now, just shy of 40 years later, Bear feels like a new kind of fable, the sort of story that people will try to parse meaning from hundreds of years from now. This is, in every sense of the word, potent stuff. - Paul Constant

The first thing you need to know about Marian Engel’s 1976 novel Bear is that it is about a woman who has sex with a giant bear. Not a metaphorical, figurative, concept-within-a-creature bear: a real, furry, wild brown bear. There’s more to it than that, but why bury the lead?

The second thing you need to know, however, is that this is not some fringe underground chapbook: it won the Governor General’s award—the highest Canadian honour for the literary arts—in a year in which the jury included Mordecai Richler, Margaret Laurence, and Alice Munro.

We’re talking about Bear right now, though, because someone recently posted its cover and some particularly raunchy sections of the book to Imgur under the title, “WHAT THE ACTUAL FUCK, CANADA?” There was even a little boost in e-book sales after the book’s cover—an illustration of a lithe, topless woman with flowing brunette locks being embraced from behind by a bear standing on its hind legs—went viral. It looks like a Harlequin romance novel: ursine Fabio and his eager human companion, lost together, alone in a world that will never understand the depths of their potentially life-threatening interspecies love.

The story, ultimately, is not as sexy as all that, though it’s not without its moments of high erotica. It begins with a librarian named Lou heading to an island in remote northern Ontario to catalogue the library of an estate bequeathed to the institute for which she works, and, as luck would have it, finding a bear living on the property. Their affair truly blossoms two-thirds into the book, though, when, one night, she’s lying by the fire with the bear, feeling incredibly lonely. Overheating, Lou takes off all her clothes and proceeds to “make love to herself,” as women are wont to do. The bear, apparently knowing how to take a hint, starts to lick her—as bears are wont to do.

As the bear begins to survey the landscape, Lou remarks upon his “moley tongue,” which is, “as the cyclopedia says, vertically ridged.” (Ever the librarian, our Lou—her head in the books even as the head of Stephen Colbert’s number one threat to America is between her legs.) After a few laps, Lou begins to emit little horse-like “nickerings,” and goes on to call the episode, on the whole, “warm and good and strange.” This is probably as accurate a description as possible of the experience of reading Bear. It’s remarkably poetic: “Bear,” Engel writes, “take me to the bottom of the ocean with you, bear, swim with me, bear, put your arms around me, enclose me swim, down, down, down, with me.” And, “Bear, I cannot command you to love me, but I think you love me. What I want is for you to continue to be, and to be something to me. No more. Bear.”

As time goes on, Lou realizes she’s in love with the bear. Bear, being a bear, does not reciprocate her feelings. Is there a more total rejection than being turned down by a wild animal? He can’t even get an erection for her, “his prick [not coming] out of his long cartilaginous sheath.” In one desperate moment, Lou pours honey on herself to entice the bear to stay. “Once the honey was gone,” though, “he wandered off, farting and too soon satisfied.” It’s possible to see Lou, who has had bad luck with men in her past, as a stand-in for Engel herself, who was going through a divorce of her own while writing the book, imbuing it with equal parts empowerment and loneliness. Bear is dedicated to “John Rich—who knows how animals think.” John Rich was Engel’s psychotherapist at the time.

As time goes on, Lou realizes she’s in love with the bear. Bear, being a bear, does not reciprocate her feelings. Is there a more total rejection than being turned down by a wild animal?

Canadian Literature is sometimes prematurely marginalized in the minds of readers for its supposed over-reliance on rural narratives and abundance of stories about humans at some sort of critical or bittersweet impasse with nature; imagine a CanLit drinking game in which you have to empty your glass every time you read the words, “the sound of the loon cry.” But Bear subverts the cliché: here, after all, is a woman actually getting down on all fours and presenting herself to an animal, almost as if to say, “You think we love nature? Oh, I’ll show you how much we love nature.”Bear garnered largely favorable reviews upon its release, finding support among respected writers and editors. As Canadian novelist, playwright, journalist, and fellow GG winner Robertson Davies wrote in a letter to Engel: “I’m fearful that the book might not be taken as seriously as it is intended and that you might be exposed to comment and criticism of a kind which, in the long run might not be helpful to you.” Considering the context of the book’s current moment of Internet fame, it’s tough to argue with Davies’ assessment. One notable pan at the time came courtesy of the critic Scott Symons, though, who, in his West Coast Review essay “The Canadian Bestiary: Ongoing Literary Depravity,” called the book “spiritual gangrene… a Faustian compact with the Devil.”

But if the book were all bear-on-broad action, it wouldn’t have the resonance it does today. It’s not simply a bizarre bestial farce; it’s a modern Canadian fable, an ironic play on romantic pastorals, and, above all, totally readable. Margaret Laurence wrote in praise of the book, calling it “fascinating and profound… [a] moving journey toward inner freedom, strength, and ultimately toward a sense of communion with all living creatures.” It won the Governor General’s award because of the strength of its writing, and because it challenges the reader as much as it strikes an emotional chord. It was published towards the tail end of second-wave feminism in North America, as women’s sexual empowerment was being pushed to the foreground; it wasn’t just gonzo—it was the zeitgeist. Recently, author Andrew Pyper wrote a defense of Bear, recommending it to readers “not because it’s a feather ruffler of a book … [but] because it brings something to the conversation that wouldn’t be spoken if we didn’t read it, if we kept things strictly appropriate. Bear is brave. We should be too.”

The book was far from Engel’s only significant contribution to CanLit. None of her other novels were quite as noticed or acclaimed, but the small group of Toronto writers that organized the Writer’s Union of Canada did so on her front porch in 1972; she was elected chair at its formation, and spearheaded the Public Lending Rights, which gave authors and editors payment for their titles in library circulation.

Engel died in 1985; we’ll never know how she might have felt about her sudden burst of Internet fame, four decades after the fact. But her place in history is secure: a friend to publishing, an award-winner alongside the authors of The Diviners, The English Patient, and The Stone Diaries, and a woman who, one day in the tumultuous 1970s, sat down, and, with full command of her craft, wrote of a lonely librarian in love with a bear: “She cradled his big, furry, asymmetrical balls in her hands.”

- Sara Bynoe

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.