Meredith Quartermain, I, Bartleby, Talonbooks, 2015.

Read the first story from this book on Meta-Talon.

excerpt

An Interview

An Interview with Meredith Quartermain, Part 1

An Interview with Meredith Quartermain, Part 2

In these quirkily imaginative short stories about writing and writers, the scrivener Quartermain (our “Bartleby”) goes her stubborn way haunted by Pauline Johnson, Malcolm Lowry, Robin Blaser, Daphne Marlatt, and a host of other literary forebears. Who is writing whom, these stories ask in their musing reflections – the writer or the written? The thinker or the alphabet? The calligrapher or the pictograms hidden in her Chinese written characters?

Intimate jealousies between writers, wagers of courage and ambition, and histories of the colours violet and yellow are some of the subjects in the first section, “Caravan.” Struggles of mothers, fathers, and sisters (and the figures drawn in the Chinese written characters that represent them) unfold as tales of love, death, and revenge in the group of stories in the second section, “Orientalisme.” In “Scriptorium,” the third section, we find out how Bartleby’s father, a Caucasian cook specializing in Chinese cuisine, got Bartleby into writing in the first place. In the fourth series of stories, “How to Write,” we learn how Bartleby loses her I while meeting Allen Ginsberg, Alice Toklas, and a real Chinese cook who works in a fictional house of Ethel Wilson, and how Malcolm Lowry’s life came to an end. The fifth and last section, “Moccasin Box,” investigates how a Sebaldesque Bartleby is silenced by Pauline Johnson.

Taking its cue from genre-bending writers like Robert Walser and Enrique Vila-Matas, I, Bartleby cunningly challenges boundaries between fiction and reality.

“I, Bartleby is Meredith Quartermain’s gift to the careful reader who lives to be awestruck. Not long into this intertextual and intercultural opus, you understand that you’ll be reading it not just in the future, but in the future after the future; the ineluctable pleasure of it expects your return. As the author says, ‘I’ve opened a box I can’t close’ – and so it is that I feel about I, Bartleby: the text is open, the words are out, and Meredith Quartermain’s work explodes all notions of containment.”

– Wayde Compton

“Short stories? Prose poems? Feuilletons? These evocative meditations are imaginative flânerie, each one opening a portal to a world of personal nuance, archival investigation, the mysteries of marking, writing, and interpreting, and the cost these exact … Each is a portal to the foreignness and oddness of the everyday, the paths walked … With rich and quirky metaphors evoked by passing encounters, with her proud gendered sensibility while facing culture, with vivid details of the real and the imagined looping excitingly together – Quartermain has created a writerly book of great panache.”

– Rachel Blau DuPlessis

“In I, Bartleby, Meredith Quartermain chips away the deadwood of dry syntax exposing the raw and revealing the new. Each line is a branching event budding fresh images and ideas. An exciting read.”

– Grant Buday

“Meredith Quartermain continues to extend her impressive exploration into poet’s prose and the ‘fictive certaintie’ of an alternate imaginary. What I love about these prose feints at their various subjects is that genre is impossible to pin down – prose poems? Essays? Fictions? Memoir? Like Borges, it’s impossible to tell and beside the point. What we encounter is unmistakably thinking – in, through, and at times it even seems by language, from which the authorial Bartlebys have excused themselves. This is masterful writing about writing and difference – with a difference – where we ‘swim among the constitution of words,’ place, and memory.” – Stephen Collis

“Quirky” is the first adjective used in the blurb on the back of Meredith Quartermain’s short fiction collection I, Bartleby. I decided to take out my OED at about thirty pages into the book to be sure my understanding of “quirky” wasn’t skewed somehow by growing up on television (my first memory of the word “quirky” was its defensive use by my father during a family viewing of Napoleon Dynamite, when my mother’s chosen adjective was “stupid”). It seemed, to me, to mean silly, or not serious. Quirky feels somehow applicable to Wes Anderson but not David Lynch, to Jonathan Franzen but not David Foster Wallace, or to Thomas Pynchon but certainly not to William Gaddis. The dictionary defines quirky as “characterized by peculiar or unexpected traits,” so I guess what is meant by “quirky” here is publisher-speak for fiction that uses subtle observations to evoke something about the quiet desperation that surrounds North American adult life; at least this applies to the book’s first section, Caravan. This first section, for me, introduced a feeling of self-consciousness or a kind of distorted self-perception, not all that surprising considering most of these stories are about writing or writers in one way or another.

Part of the fun of reading Quartermain is that she can begin with tight-lensed, microscopic close-ups, and long, Proustian observations that draw from fragments of childhood and expand into the moments that triggered them, before pulling out and leaving us with the stone wall of a post-daydream reality. “We don’t sweep around curves, jut up risers, or swoop down descenders, curling and uncurling a c or an s, looping and knitting our letters. Nowadays our neurons manage rows of on-off switches, fingers wired to three or four buttons commanded by imagined letters, the conveyancers of thought, printed in our brains. Except for lists of milk, bread, and apples. Or receipts handed out by someone taking away a rug to clean. Or the cramped script on tiny lines of dental records using the universal tooth numbering system: watch 7; replace amalgam in 12 and 29; scaling, two units; recommended extraction 32.”

Like Proust, Quartermain works in the space between moments, between what is happening and the faint mnemonic triggers that exist in momentary webs of memory and thought. In this way she seems to enable us to experience abstractions and imagery on a kind of subconscious level. “…he took me through rain-soaked streets past darkened windows of the Chinese Times and the shops that sold incense, bamboo fans, tea, and golden roaring lions, shops of mannequins wearing silk sheaths of sapphire, turquoise, scarlet, and pearl embroidered with dragons or plum blossoms or paisley teardrops, high-collared dresses that hugged hips and bust, had slits up the thighs, and a row of frog buttons closing the placket over the right breast.”

The stories read very much at the speed and flow of thought, and the author’s approach is every bit as smart and imaginative as Barth or Barthelme, although nothing feels like a game (actually, there is one story titled “There Real Fictional House of His Imagined Film Director,” in which she does, in a fun way, kind of jerk us around a bit); these are more meditative, and Quartermain is more a companion than a puzzle maker. She’s getting at something important about us, about the torments surrounding banalities, and memories, and childhood, and writing. The collection’s average story length is about one-and-a-half pages, which seems to be the size of the author’s structural comfort zone: those longer than four pages begin to lose steam and wrap themselves up in ways that feel awkward and unsubtle. An example of a longer-than-two-pages story that seems to lose its composure is “Scriptorium” (also the title of the third section), which begins strongly, builds delicately, and really seems to promise something as structurally gorgeous as her sentences, before diverging into what feels like a smart teenager’s viciously scribbled thoughts about the failings of her father. Structural wavering aside, the final (and longest) story, “Moccasin Box,” does an acrobatic job of solidifying themes and tying both ends of the book together in a way that many collections fail to do. Above all, it’s Meredith Quartermain’s dexterity in channelling lives and landscapes to explore the symptoms of our post-millennial malaise that make I, Bartleby both wickedly smart and fun to read. —Matthew K. Thibeault

Since the trifurcation of “Poetry” (roughly in the 18th century) into the three genres that in turn came to comprise the category of “literature” — poetry (primarily lyric poetry), fiction, and drama — the phenomenon of writers crossing the boundaries of these now three separate literary forms has not exactly been rare. Thomas Hardy was a great poet and a great novelist. Samuel Beckett was a great playwright and a great fiction writer. Edgar Allan Poe was equally adept at lyric poetry and short stories.

However, the divide between forms, especially between fiction and poetry, has arguably become even thinner, evident not only in prominent postwar writers who found success as novelists after beginning as poets (Gilbert Sorrentino, Denis Johnson, Sherman Alexie), or maintained parallel careers as novelists and poets (John Updike, Marge Piercy, Raymond Carver). It could be argued that the American fiction of the 1960s and 70s now considered “postmodern” was inherently a language-centered fiction that in disrupting conventional narrative forms substituted broadly poetic structures in their place (Donald Barthelme or John Hawkes), while some writers, nominally writing prose, were as gifted at figuration as any poet (Stanley Elkin or William Gass). More recently, writers who have been identified as the “school of Lish” (novelist, teacher, and editor extraordinaire Gordon Lish), including Gary Lutz, Diane Williams, and Christine Schutt, have brought attention to the sonic and syntactical effects of the sentence in a way that often compels us to regard one of their compositions at least as much as a poem as a “story” in order to fully appreciate its aesthetic character.

The increasing popularity of the prose poem among current poets has itself brought the two forms into closer proximity, through the confluence of prose poetry and what is called “flash fiction.” Not all writers of flash fiction, of course, regard it as a version of prose poetry, but rather as an experiment in the radical reduction of plot, character, setting, or scene to the minimum extent possible while still retaining some semblance of structure and coherence. Nevertheless, a number of such writers do blur the boundaries between prose and poetry, from both sides of the diminishing line between the two, and among those should be counted the Canadian Meredith Quartermain, whose new book I, Bartleby is labeled “short stories” on its cover but surely does come close to making that line all but imperceptible, if not simply irrelevant.

This is especially true of the shorter pieces included in the book’s first section. Generally fewer than two pages long, most of these begin with a motif or image that is then developed through elaboration, association, or something like a brief narrative. “A Natural History of the Throught” riffs on color, beginning with violet, which is “opposite yellow on the color wheel.” “Out of the Dark” begins as a riff on light, but then light strikes someone’s hand (presumably the writing hand of “I, Bartleby,” introduced to us in the first story as a sort of metafictional stand-in for the author), bringing its corpuscles to life (who prove resistant to the effort). The story is at once both a lyrical reverie and an allegory of the recalcitrance of inspiration. In what seems a throwaway remark, “I” tells us in “A Natural History of the Throught” that “I’ve lost my train of thought,” but this assertion proves to be a kind of clue to the method Quartermain uses in many of these pieces, as the author/narrator pursues a “line of thought” in a way that produces less than a well-ordered story but more than disconnected utterances.

Other sections of the book offer longer pieces, although they too can’t really be called short stories in any conventional sense. The metafictional framework established by the initial short pieces is carried through the rest of the book, reflected in section titles: “How to Write”; “Scriptorium.” Several of the pieces directly concern writing and language, among them “If I prefer not,” in which “I,” transposed to the third-person “She,” attempts to write about a Chinese man she has passed on the street, “Cloth Music,” literally a story about Chinese calligraphy, and “If I noiselessly,” in which “She” is contemplating writing a manifesto:

. . . why not a manifesto of the sentence? Crossbreed every kind with another kind — twist and turn the thought shapes — so many butterfly nets. Une manifestation of clamouring motifs. Unsentencing the sentence. Smashing the piñata of complete thought to clouds of recombining viruses.

This story takes a more poignant turn when we discover that “She” has been reflecting on this projected manifesto as she is returning from a hike to a mountaintop to scatter the ashes of her just-deceased mother, “the dust that had been her mother clinging to her jeans and boots. Breathing the dust that had been her, had made her.”

Ultimately I, Bartleby does balance out the self-reflexive gestures and its more conventionally dramatized “content.” “If I, scrivener, print a letter” also focuses on the death of the writer’s mother (the woman is again “I,” telling her own story), blending a consideration of color imagery with recollections of her mother and with an interpolated episode in which she loses a job. Here “I”’s preoccupation with writing and the otherwise dispersed references to apparent memories and life experiences come together to more firmly identify “I” as the protagonist of the book, even if an unorthodox and sometimes elusive presence. In “Scriptorium,” perhaps the most conventional and straightforward story in the collection, the writer/protagonist recounts childhood memories of her artist father, but this leads not to a melancholy meditation on loss. Instead the narrator relates her eventual estrangement from the father, when she realizes they “don’t speak the same language.” Again “life” is unavoidably implicated in “language.”

Two other stories in I, Bartleby are noteworthy as well. “The Real Fictional House of His Imagined Film Director” tells the story of Canadian novelist Malcolm Lowry and his second wife, writer Margerie Bonner, via the overlaps and echoes among their lives, as Lowry is headed to his ultimate alcoholic breakdown, and characters in their books (Lowry himself being a notoriously autobiographical writer). “Moccasin Box” focuses on 19th-century Canadian/First Nations writer and actress Pauline Johnson, whose lingering presence in and around the Vancouver landscape the narrator tracks. The story’s most conspicuous feature is its incorporation of photographs as a narrative accompaniment. Each of these stories clearly shows Quartermain’s interest in situating her own work in the context of specifically Canadian writing.

I, Bartleby is the kind of book some readers undoubtedly could find disorienting in its initial reluctance to provide those markers we most associate with “short stories.” By the end, however, the book has made its own alternative, less commonplace strategies sufficiently recognizable that going back to the beginning and re-reading, especially given the book’s relative brevity (118 pages), can be a highly rewarding experience, as Quartermain’s achievement becomes more distinctly visible.

- Daniel Green noggs.typepad.com/tre/unsentencing-the-sentence.HTML

Meredith Quartermain, U Girl, Talonbooks, 2016.

Award-winning author Meredith Quartermain’s second novel and seventh book, U Girl, is a coming-of-age story set in Vancouver in 1972, a city crossed between love-in hip and forest-corp square.

Frances Nelson escapes her small-town background to attend first-year university in the big city. “You’ve got to find the great love,” her new friend Dagmar tells her. But what makes it love instead of sex? And what kind of love bonds friends? She gleans surprising answers from Jack, a construction worker; Dwight, a mechanic and dope peddler; Carla, a bar waitress who’s seen better days; and her English professor and sailing friend, Nigel.

U Girl blurs the line between fiction and reality as Frances begins to write a novel about the people she comes to know. With seamless metafictional play and an engagement with place that has come to be Quartermain’s definitive style, U Girl tells the story of a woman’s struggle to be taken seriously – to be equal to men despite her sexual attraction to them, and to dislodge accepted narratives of gender and class in the institution of the university during the “free love” era.

In this sprawling and perceptive novel, Quartermain takes us through sexual experimentation, drugs, working at menial jobs, meditating on Wreck Beach, sailing up through Desolation Sound, and studying at the University of British Columbia.

U Girl pays homage to local haunts and literary influences in equal measure. Quartermain brings to Canadian literature a wholesome and vital female perspective in this long-awaited bildungsroman.

“Quartermain takes her readers through the lens of a young woman challenging her small town looking glass with a much wider angle. … Much like [the protagonist, Frances’s] characters in her novel [within the novel], the pace and lessons of life are far from stagnant and [Frances] continues to forge on to a new frontier.” —Pacific Rim Review of Books

“Once I was arrogant and lost”, recalled the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas towards the end of his brief life, “and now I am humbled and found. I preferred the former.” Meredith Quartermain’s second novel recounts the tale of a young woman with high dreams in low-rent housing, set in a Vancouver now fast vanishing, if not completely disappeared. A whimsical pleasure to read, and at times deeply felt and affecting, the book never quite achieves its own aspiration as a feminine Bildungsroman, though it will amuse and tease anyone who has ever been young, poor and confused about life. Which must be just about everyone.

Protagonist Frances Nelson is a small-town girl who moves to Vancouver with her boyfriend to attend UBC in the early 1970s. Hers is a world of dingy rentals and youthful aspiration, dreams and anxiety. Quartermain deftly handles a tight cast of characters, from Dwight the sleazy mechanic-cum-artist to Carla, a cocktail waitress who has seen better days. Best of all may well be Nick, the young English literature professor who cloaks his lusts with lofty references to D.H. Lawrence, encouraging Frances – the “U Girl” of the title – to believe that she might write a great novel, all the while plotting to seduce her.

For all of these pleasures, the novel’s structure suggests a certain self-consciousness. Frances progresses through various heartbreaks, career and money hassles, all recounted as she begins to write her first fiction, a work which becomes the novel you have been reading. The device of meta-fiction has a long and proud history stretching back to Hamlet and Laurence Sterne, though one wonders whether such a device best serves the author’s aims in this context.

Novels that track the psychological development of their central character, from The Sorrows of Young Werther to Tonio Kröger, tend not to further complicate the psychological aspects of their narrative with structural devices. Drama and poetry are different animals, but in the novel, especially one with the easy, demotic tone Quartermain achieves here, rare skill is required to make such legerdemain effective.

Another reason why Quartermain’s work falls a little short may be the difficulty in detecting any fundamental change in Frances Nelson’s psychological state as the story unfolds. True, she begins the book as an anxious, somewhat naive young woman, and ends as someone less deceived by others, committed to becoming a writer. However, we also learn early on that she is capable of dumping boyfriends, has sufficient sexual experience to compare her lovers’ prowess in bed, and is fiercely independent. Useful as these qualities may be, they are not ones typically associated with naïve, dreamy undergraduates.

Certain passages have punch aplenty, particularly Frances’ remarkable account of her liaison with Dwight, yet there’s little sense that Frances has changed or developed significantly in the end. Neat touches, as when Dagmar and Frances type up each other’s work and sharpen their critical acumen in the process, should be admired; but the scaffolding on the edifice, this novel’s pipework, is too visible for it to be completely successful. While admiring the careful plotting and deft characterization, a more obvious denouement might have helped Quartermain show how Frances has grown, and why that change matters to us.

These reservations aside, readers will happily immerse themselves in the novel’s lost Vancouver – a time when downtown had beer halls rather than gastropubs and students went to libraries to read books and share typewriters rather than search for results on their hand-held devices. Quartermain’s evocation of the wilderness that lay beyond the city at that time – eating oysters on beaches in the Gulf Islands, the ever-present spectre of the mountains – might be the greatest pleasure on offer here, and a far cry from the forest of steel and glass found in today’s city centre. Meredith Quartermain almost makes you believe student pasta can be as evocative as Proust’s Madeleines, and for that we should thank her. - James W. Wood

U Girl is a coming-of-age tale about a small town girl who moves to Vancouver in 1972 to attend the University of British Columbia. As she seeks to discover and define herself among the new people she encounters in the unfamiliar city, she ponders the disparities between men and women and questions the relationship between love and sex.

Former UBC English Professor Meredith Quartermain has truly outdone herself this time. Through her poetic depictions of Vancouver landscapes and unique yet relatable characters, she weaves together a story that pulls the reader into the fictional reality residing within the pages of U Girl.

This bildungsroman is an extraordinary new addition to Canadian literature as Quartermain beautifully portrays British Columbia in her descriptions of Wreck Beach, Desolation Sound, and UBC among other local sites. This should make the novel an interesting read for UBC students who are acquainted with these places. Some students may even find themselves familiar with the protagonist’s experiences of taking notes in lecture halls and managing a crush on a professor. U Girl captures a number of details about life as a UBC student and even makes reference to the Ubyssey, as one of the characters is said to have written an article for it. This truly brings the characters to life as their relatable experiences allow them to seamlessly blend with reality. The fusion of fiction and reality is further achieved through metafiction as the protagonist seems to be drafting ideas for the novel that is being read. She contemplates how she should portray the individuals she encounters and how she herself should be depicted. Although it may seem perplexing at first, the self-referential nature of U Girl makes it a fascinating read for introspective readers.

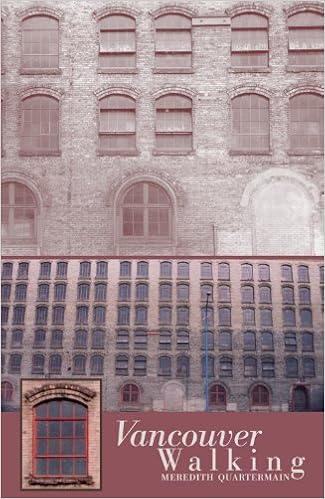

Quartermain has made a name for herself as a Canadian writer through her previous literary works including Nightmarker and Recipes from the Red Planet. Her collection of poetry titled Vancouver Walking earned her the 2006 Book Award for Poetry.

The literary skill for which she is known nationwide is evident in her newest novel, U Girl. Quartermain possesses a talent for calling attention to real world problems as she brings the treatment of women into the spotlight, broaching the topic of domestic abuse when the protagonist overhears a dispute occurring in her building a few doors down.

Readers may begin seeing themselves in her shoes while reading the story, as her journey of self-discovery mirrors emotions and insecurities all too familiar to all who have tread the path to find their purpose and meaning in life. However, this does not mean that the protagonist, Frances Nelson, is in any way cliché. Frances has her own unique personality, which shines through in her voice as she narrates the story. Her curious and introspective nature reveals questions and shocking new perspectives that readers may not have considered before.

Readers should prepare themselves for a tidal wave of emotion, reflection, and new perceptions when they dive into Quartermain’s latest masterpiece. - Alyssa Low, Ubyssey

As a meta-narrative about the process of writing a novel, U Girl succeeds because novelist Meredith Quartermain has already thought through the writing process, so that her narrator Frances Nelson asks the narratological and existential questions Quartermain has, herself, already asked and answered. Quartermain reveals her philosophical themes by exploring how a novel finds and expresses itself. The novel opens with this confession: “Of course Frances Nelson isn’t my real name, and we weren’t from Cultus Lake, not the one on the map, but we were from a cultus lake, somewhere, nowhere” (1). In narrating her own coming-of-age story, Frances could be Mabel or Priscilla or Georgina because she is searching for her identity. As a fledging writer she wonders what “real writers call themselves” and who Frances would be in her own novel (21). She finds her answers as she writes.

While Frances could be coming from anywhere, the beginning of her quest brings her to Vancouver.

By setting the novel in her own backyard (in 1972), Quartermain draws beautifully on her knowledge of this region using pin-point geography to describe south-western British Columbia. She situates U Girl mostly within the Vancouver setting, with such specific nods as those to Spanish Banks, CKLG radio, Georgia Straight, and “the triangle between Broadway, Main and Kingsway” (22). On the one hand, we have a universal coming-of-age story, and on the other, the vivid local setting rich in its use of detail.

Quartermain structures the frame of U Girl around “a bunch of people living in a house” (88), Jack, Carla and Dwight, who live with Frances. They become the characters in her novel, taking on fantasy lives that diverge and cross with their own lives. The place where Frances goes to find her creativity, the “[w]indows in the dark mansion of [her] brain” (72), is the place her Prof Nigel calls her “darkness,” the place that attracts him to her and that he thinks her novel should be about (62). However, the windings of the novel follow more than the journey of Frances discovering what her darkness is; it also explores her “tree and mountain” self (119), her vitality, her “wildness” (206).

Frances’ exploits resonate from within their early 1970s culture: she and her girlfriends can have sex before marriage because “marriage was not for us” (3); she can experiment with weed and hash, maybe go to “be-ins and happenings” (73), check out Wreck Beach, all the while attending UBC as an undergrad in English literature.

Introduced and developed as a character willing to take risks, Frances quickly eases herself out of one relationship with Joe, and then she must learn to answer to the call “HEY U GIRL” (25) from Carla her new rooming/house mate. Frances subsequently moves into another, just as unsuitable relationship, with her professor Nigel, the object of her desire, “daring to think my wildness could match his Shakespeare” (169). After the end of her course with him, when he suggests she read Proust “because he showed how magical names were” (144), Frances eagerly plays the name game as they wend their way up to Desolation Sound on his sailboat, Windsong. However, the name of their destination becomes too prophetic, later, when he doesn’t call after the trip, and she finds herself spurned and desolate. The novel’s plot is not a conventional linear narrative where girl meets boy, faces crisis, and ends up with her Romeo. Quartermain is much more focused on her heroine’s identity quest than to allow her novel to become, as Frances asserts to Nigel, “some hokey formula romance” (116).

At the same time as Frances is trying to write her novel, she’s also trying to educate herself, find out who she is and where she fits into this particular world in which she’s found herself. In order to make enough money to continue with her studies in English, therefore, Frances also slings drinks at the Biltmore bar and files claims at an insurance company.

As the story develops, Quartermain evokes some wonderful, precise imagery: when Frances tries to find out what’s going on with a “domestic quarrel” (84) in Jack’s room, “[t]he grubby little fridge kept its blank face shut” (83). Later, at the Biltmore bar, brash UBC students “seethed and swirled around each other like rushing water crashing and tumbling through rapids, as certain as a river of where they were going” (91). Frances, thinking of her roots growing up, admits, “I’d crawled their forests [around Cultus Lake] like a flea in the fur of a bear” (144). Conversely, Quartermain invents a few tortured tropes: “Echoes of ‘down’ and ‘out’ slalomed down the white slope of this thought leaving interlocking zigzags in its pristine powder” (77). Perhaps this image reflects the fact that Frances is high on hash at the time! Quartermain matches her particular style with a highly literary tone. It’s a novel rife with so many references to literature, music and art that the cover art itself offers the reader a preview, with its west coast rendering of Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott.”

By her journey’s close Frances discovers where she fits in is not where she might like to think she would. Ironically, her infatuation with her well-heeled university girlfriend Dagmar causes her heartache, just as her love for her English professor proves to be one-sided. Yet a sense of belonging can come from odd places, as Frances realizes when she makes some deeper connections with each of her roommates, especially campy Carla. Yet, even more surprising, who would expect that Frances could feel such powerful sensations with “sleazy Dwight” (185) that she could not experience with Nigel, despite his “cool John Lennon stares” (140)?

In the end, we are drawn convincingly into Frances’ world. Readers of U Girl will also appreciate and enjoy recognizing so many local haunts revealed in these pages. The ones who are likely to be the most enchanted are those who can identify the myriad allusions, relate to the trials and triumphs of writing, or, like Frances, aspire to do so and grow in the process. - Andrea Westcott

Meredith Quartermain, Nightmarker, NeWest Press, 2008.

There's an automatic impulse within the human species, the way its cities spring up all over the planet just as ant colonies do. Humans reproduce by way of towns and metropolises, replicating the bee-dances of the Romans, Greeks, and Babylonians, unconsciously invoking rituals of the past in tranceful reveries of the future.

In expeditions to City Hall, the police station, the sugar refinery, and the courthouse, Nightmarker explores the human city as an animal behaviour, a museum, and a dream of modernity. It also records the journey of Geo, an earth-geist, who struggles to comprehend humanity's siege of Earth while enabling us to examine the human condition, bound as it is by the drive to evolve, multiply, and simply exist

Meredith Quartermain, Recipes from the Red Planet, Book Thug, 2010.

Suppose fiction is a mansion of mirrors where narrative, setting and plot are characters, and suppose this castle is haunted by Martians constantly rearranging, reversing and transElating its furniture of myths, fables and nursery rhymes. Let’s play space-wars, say the Martians, it’s just a game—our guns shoot words. You zap a Martian. She disappears, but it turns out this Martian is a master chef who even created a recipe for life. How are you going to get the recipe back?—to rebuild her carnival laboratory?

“Near the end of these wry and witty pages we are told of someone from Ontario, and the same page asks, Where is Ontario from? The same could be asked of From the Red Planet, or Quartermain’s ingredients: her lists, her seemingly endless strings of relations made tastier by the weight of form, be they tales, news reports, voice imitations. Metaphysics, local history, classics, astronomy—the reference range is vast, but so is the contemporary experience. A rising crust!” —Michael Turner

“Recipes from the Red Planet cooks books for deep-space dining, rolls out the dough of language and shapes it into buttery crescents that are supernaturally textured and interactive with daily life. Meredith Quartermain’s solar system blows asteroid dust through the patriarchy and oven roasts the alphabet to a lovely golden crisp. Whipped by interplanetary winds we meet the immortals of the ancient world inverted and propelled into negative space. Their ground delineates our figures, neatly attired in dresses we’ve sewn ourselves from Simplicity patterns. Here are the recipes that will free Rapunzel from her tower. Here are all the blue radishes you can eat.” —Larissa Lai

“These stories simply delighted me. Their broken turns of logic and semantics are lovely and reflect, somehow, the way I think. To read and reread.” —Erín Moure

Meredith Quartermain, Matter, Book Thug, 2008.

What if words evolved in species and genera just like birds and dinosaurs? What if you classified them in kingdoms and families? Made a phylogenetic tree with orders of Space, Matter, or Intellect. Gravity and Levity as classes of MATTER.With Density, Rarity, Pungency, Ululation. Would this matter taxonomy speak of the out-there, the non-human? Or the in-here--the human mind, the sorting, reasoning human--homo linguis the word maker, the world maker? Formally innovative, Matter explores Roget's taxonomy, rummaging its taint of globalism and social Darwinism, unearthing relations between humans, language and the planet. Matter asks what if words are so many birds, chirping and chattering? What is thought? What is knowledge? What's your life-list of words?

“What matters? In a poet this one, the plan of classification generates from both biological and linguistic matter. Meredith Quartermain delves into the gurge of regurgitates, the specific gravity of the homo-species, the taxonomy of the tongue. ‘Good morning. Here is history.’ Each poem an organ-ic legend revealing how etymology organizes the body, how ecology organizes the mind. What matters.” — Nicole Markotić

“Matter is like dipping oars in a cosmos-world/words, riotous and voluptuous festival of language. I truly loved it and it deserves to win all kinds of accolades and prizes—which means it probably won’t.” — Lola Lemire Tostevin

“In one poem, she refers to ‘a quaggy wild / around Man’s island of sense.’ That ‘quaggy wild’ is exactly where this inventive poet sets up shop, blurring the division between animate and inanimate, and fabricating her own brand of metaphysics for understanding how the world works.” — Barbara Currin for The Toronto Star

“The poems of Matter are prescient, daring, and push readers to unthink the things that they think even as they read.” — Kit Dobson

Meredith Quartermain, Vancouver Walking, NeWest Press, 2005.

Journey along Vancouver’s city streets, past its landmarks, through the sounds and smells of Chinatown. Ramble along the seawall on English Bay, ride the curving streets to Kitsilano on a winter afternoon, and experience the vibrant sights and sounds of the city’s history as it jostles for a place in the present.

“In Vancouver Walking, Meredith Quartermain sights the coordinates of tangible and historical attentions as she moves through an amazement of place and language. The word here is foot and eye, step by step, crisscrossing the city with the grids and layers of its own minute particulars and articulating the truth of the imagination, the dynamics of the intersect. These poems listen carefully to the yearning of place, the kind of naming a city answers to.” - Fred Wah

Meredith Quartermain, Rupert's Land, NeWest Press, 2013.

At the height of the Great Depression, two Prairie children struggle with poverty and uncertainty. Surrounded by religion, law, and her authoritarian father, Cora Wagoner daydreams about what it would be like to abandon society altogether and join one of the Indian tribes she’s read so much about.

Saddened by struggles with Indian Agent restrictions, Hunter George wonders why his father doesn’t want him to go to the residential school. As he too faces drastic change, he keeps himself sane with his grandmother’s stories of Wîsahkecâhk.

As Cora and Hunter sojourn through a landscape of nuisance grounds and societal refuse, they come to realize that they exist in a land that is simultaneously moving beyond history and drowning in its excess

"Canadians are – very belatedly – starting to come to grips with the reprehensible treatment of First Nations peoples in their history and its legacy of pain in the present; Quartermain’s novel contributes to that process."~ Publishers Weekly

“Dispossession in various forms haunts this historical novel. Wild longing, tart dialogue, and acute perception bring Meredith Quartermain’s child-narrators alive in their dustbowl world of few options. A remarkable first novel.”~ Daphne Marlatt

“Reminiscent of Sheila Watson, Quartermain weaves the richness of myth with a parched, impoverished landscape. Enduring family histories sustain two youngsters from opposite sides of the tracks as they converge in a desperate trek through Rupert’s Land.”~ Vanessa Winn

“Quartermain handles each character with exquisite care backed with extensive research allowing each to seek ‘another way to be’ so that we can search our own biases too. Written precisely and poignantly, Rupert’s Land seems destined to become a Canadian classic.”~ Jacqueline Turner

"The background of despair is familiar from writers like Sinclair Ross, but the way Quartermain brings an age to life while staring unflinchingly at its attitudes and injustices through the eyes of children is reminiscent of To Kill A Mockingbird. The same innocent intelligence that characterizes Scout in that novel informs Cora’s and Hunter’s acute observations, conveyed in a blend of pitch perfect dialogue and inner voices." full review ~ Margaret Thompson

"The best fiction brings serious issues into sharper focus. Rupert’s Land did this for me because the storyline includes Indian residential schools in Canada — although this is the furthest thing from a preachy book. Gifted Canadian poet Meredith Quartermain shows rather than tells." full review ~ Linda Diebel

Meredith Quartermain was born in Toronto but grew up in rural British Columbia, on the north end of Kootenay Lake. Botany, Latin, Math, Philosophy and Ecology intrigued her at UBC. She is the author of Terms of Sale (1996), Wanders [with Robin Blaser] (2002), A Thousand Mornings (2002), The Eye-Shift of Surface (2001), and Vancouver Walking (2005), winner of the BC Book Awards Poetry Prize. She lives in Vancouver where she runs Nomados Literary Publishers with husband Peter Quartermain.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.