J.J. Voskuil (1926-2008) stands alone in Dutch literature. In 1963 he published Bij nader inzien (On Second Thoughts), a twelve-hundred-page novel which describes with photographic precision the lives of a group of students in Amsterdam between 1946 and 1953. For thirty-three years Voskuil was a one-book author and this book seemed to be attaining cult status, especially after its successful adaptation for television in 1991. Until 1990 Voskuil worked at the Bureau for Dialectology, Folklore and Onomastics. Following his retirement he wrote the novel cycle Het Bureau: seven books, a total of 5,500 pages, published between 1996 and 2000. Part two of the cycle, Vuile handen (Dirty Hands), has been shortlisted for the 1997 Libris Literature Prize. A year later Plankton, volume three of the cycle, was awarded the same Libris Prize.

Never before has the dry humour and occasional tragedy of office life been described as thoroughly as in this cycle of novels. The appearance of the first two parts, Meneer Beerta (Mr Beerta) and Vuile handen (Dirty Hands) was enough to guarantee the cycle’s status as a classic of Dutch literature. The books mercilessly describe the frivolity, the petty irritations and teasing, the conniving and crawling, the hierarchy, the unnatural suppression of emotion, and the alienation that insidiously strengthens its hold on people over the years in which they are obliged to spend their days together in a closed room.

Gradually the Bureau itself emerges as the real main character: an institute which draws in its staff every morning with a magnetic power, encloses them, wrings them dry, then spits them back out at the end of the working day.

J.J. Voskuil has produced a sublime parody of academic specialisation. Maarten Koning, the fictional alter ego who first appeared in Voskuil’s previous book Bij nader inzien, joins the Bureau for Dialectology, Folklore and Onomastics in 1957, and is charged with systematic research into the most obscure of folk traditions: the belief in elves, the uses of scythes and harrows, rye bread and cradles. Nobody knows what purpose the research is meant to serve, but everyone does as they’re asked. Voskuil’s wry method of recording a scene in the space of a few pages and then cutting to another gradually builds up to create a complete picture of a surrealistic agency which would do Kafka proud.

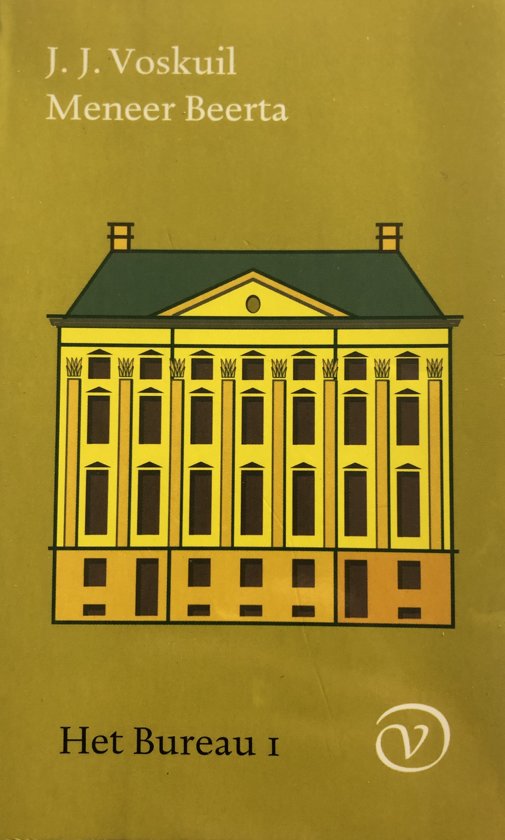

Part One, Meneer Beerta, is a brilliant portrait of the institute’s director. This ironic and elusive figure is the personification of Maarten Koning’s view of academic research: a version of occupational therapy which provides status and income for its practitioners, who therefore maintain a prudent silence when outsiders and inferiors question its meaningfulness. In Vuile handen, set between 1965 and 1973, the period of Vietnam and student unrest, Maarten has become head of the Popular Culture Department and is gradually trying to surround himself with a circle of kindred spirits. He has grown up and now identifies with his role. From this new position he watches his student ideals being slowly whittled away. Het bureau is a profoundly comical, detailed and moving depiction of that world of bosses and wage slaves which ultimately imprisons everyone.

Het bureau is beyond a doubt the absolute literary sensation of the last thirty years. - Theodor Holman

What makes the novel so special is the way it magnifies human failing. The Bureau is the universe in a pocket edition, an allegory for society. The fact that there is still plenty to laugh at, mainly because of the sublime style and the often comic dialogue, makes human fate bearable. - Jury’s Report Libris Literature Prize 1997

Despite the honest, diary-like, unadorned style which clearly betrays the spirit of Alberts, Elsschot and Nescio - and could one ask for better writers as guardian angels? - the novel ultimately reveals an exceedingly sophisticated construction. - H. Brandt Corstius

A really masterly novel cycle […] much funnier than one might at first think. Reading it is, and for once this deserves to be said, a first-class experience. - T. van Deel

Interest in the megalomaniac novel cycle Het Bureau, is starting to assume unprecedented proportions. The appearance of the fourth part of the ‘world’s longest novel’ was a major news item and people rushed to the bookshops to pick up their copy of the latest volume. Readers who have followed Maarten Koning, Voskuil’s alter ego, through the first three volumes find themselves hooked on Koning’s melancholy musings, his acuteness and his merciless descriptions of his colleagues.

J.J. Voskuil has produced a sublime parody of academic specialisation. Maarten Koning, the fictional alter ego who first appeared in Voskuil’s previous book Bij nader inzien, joins the Bureau for Dialectology, Folklore and Onomastics in 1957, and is charged with systematic research into the most obscure of folk traditions: the belief in elves, the uses of scythes and harrows, rye bread and cradles. Nobody knows what purpose the research is meant to serve, but everyone does as they’re asked. Voskuil’s wry method of recording a scene in the space of a few pages and then cutting to another gradually builds up to create a complete picture of a surrealistic agency which would do Kafka proud.

Part One, Meneer Beerta, is a brilliant portrait of the institute’s director. This ironic and elusive figure is the personification of Maarten Koning’s view of academic research: a version of occupational therapy which provides status and income for its practitioners, who therefore maintain a prudent silence when outsiders and inferiors question its meaningfulness. In Vuile handen, set between 1965 and 1973, the period of Vietnam and student unrest, Maarten has become head of the Popular Culture Department and is gradually trying to surround himself with a circle of kindred spirits. He has grown up and now identifies with his role. From this new position he watches his student ideals being slowly whittled away. Het bureau is a profoundly comical, detailed and moving depiction of that world of bosses and wage slaves which ultimately imprisons everyone.

Het bureau is beyond a doubt the absolute literary sensation of the last thirty years. - Theodor Holman

What makes the novel so special is the way it magnifies human failing. The Bureau is the universe in a pocket edition, an allegory for society. The fact that there is still plenty to laugh at, mainly because of the sublime style and the often comic dialogue, makes human fate bearable. - Jury’s Report Libris Literature Prize 1997

Despite the honest, diary-like, unadorned style which clearly betrays the spirit of Alberts, Elsschot and Nescio - and could one ask for better writers as guardian angels? - the novel ultimately reveals an exceedingly sophisticated construction. - H. Brandt Corstius

A really masterly novel cycle […] much funnier than one might at first think. Reading it is, and for once this deserves to be said, a first-class experience. - T. van Deel

Interest in the megalomaniac novel cycle Het Bureau, is starting to assume unprecedented proportions. The appearance of the fourth part of the ‘world’s longest novel’ was a major news item and people rushed to the bookshops to pick up their copy of the latest volume. Readers who have followed Maarten Koning, Voskuil’s alter ego, through the first three volumes find themselves hooked on Koning’s melancholy musings, his acuteness and his merciless descriptions of his colleagues.

Many people are no doubt shocked and amused to recognise situations from their own workplace. What makes Het Bureau so special? For a start, of course, its sheer size. In no other novel is the daily routine at work described at such length. ‘This book couldn’t be any shorter,’ said Voskuil in an interview. ‘When you work in an institute like mine, it takes a long time to get to know everyone. Everyone is so identified with their role that really dramatic events don’t occur. Only after years does everyone gradually emerge as an individual. It’s only in the details that you make discoveries.’

Voskuil is right. In the seven volumes that will eventually make up the cycle, every little wave, every ripple is described so tellingly that the reader is never bored. The grating repetitions, typical gestures and expressions - as in a soap opera - have a hypnotic effect. Voskuil’s penetrating style fits in perfectly with the ethos of the Office: unadorned and scholarly precision. It is the combination of size and detail that enables the reader to experience both the humour and the underlying tragedy of Maarten Koning. Het A.P. Beerta-instituut, the fourth volume, also forms a chronicle of the 1970s and the way that the changes in society in this decade are commented upon by the people at the Bureau.

At the same time all these elaborate rituals typify the hopelessness of Maarten Koning’s life and work. Even though he does not believe in the value of scholarly research, he sees it as his duty to stay, finish his work and maintain the illusion of solidarity with his colleagues. All is futile. Het bureau is a profoundly comical, detailed and moving depiction of that world of bosses and wage slaves which ultimately imprisons everyone.

Only one thing counts for J.J. Voskuil: the truth. He does not venture into fantasy in his novels, but rather sketches his recollections of a particular period or person with a rare, sharp eye for precision. In Bij nader inzien (On Second Thoughts, 1963), his mammoth debut novel about the friendship between a number of young literary students just after the war, the meticulous description of their behaviour, their words and their deeds leaves you with an uncanny impression of how it feels for Maarten Koning, Voskuil’s alter ego, to be betrayed by his friends.

Voskuil is right. In the seven volumes that will eventually make up the cycle, every little wave, every ripple is described so tellingly that the reader is never bored. The grating repetitions, typical gestures and expressions - as in a soap opera - have a hypnotic effect. Voskuil’s penetrating style fits in perfectly with the ethos of the Office: unadorned and scholarly precision. It is the combination of size and detail that enables the reader to experience both the humour and the underlying tragedy of Maarten Koning. Het A.P. Beerta-instituut, the fourth volume, also forms a chronicle of the 1970s and the way that the changes in society in this decade are commented upon by the people at the Bureau.

At the same time all these elaborate rituals typify the hopelessness of Maarten Koning’s life and work. Even though he does not believe in the value of scholarly research, he sees it as his duty to stay, finish his work and maintain the illusion of solidarity with his colleagues. All is futile. Het bureau is a profoundly comical, detailed and moving depiction of that world of bosses and wage slaves which ultimately imprisons everyone.

Only one thing counts for J.J. Voskuil: the truth. He does not venture into fantasy in his novels, but rather sketches his recollections of a particular period or person with a rare, sharp eye for precision. In Bij nader inzien (On Second Thoughts, 1963), his mammoth debut novel about the friendship between a number of young literary students just after the war, the meticulous description of their behaviour, their words and their deeds leaves you with an uncanny impression of how it feels for Maarten Koning, Voskuil’s alter ego, to be betrayed by his friends.

And in Het Bureau (The Bureau), his seven-part, 5,500-page novel, he analyses the conduct of civil servants at a scientific institute in minute detail in an equally humorous and vicious manner, dissecting his colleagues with a razor-sharp scalpel. On the basis of his findings, Maarten Koning concludes that the camaraderie at work is just an illusion.

The same theme returns, essentially, in his latest book, Requiem for a Friend. The story of the friendship between Han Voskuil and Jan Breugelman, two boys from the Hague who grow up together and maintain a stormy relationship in later life through letters and meetings, also finishes in deception. There is, nevertheless, one big difference. Unlike Voskuil’s earlier work, here the major characters appear under their own name (only Breugelman’s has been altered slightly for reasons of privacy) and the book is written in the first person.

Voskuil evidently wished to make his new novel more personal than his previous books. More authentic. The effect is enhanced by the continual quotes from the letters written to him by Jan Breugelman in the course of their friendship. Breugelman was a manic depressive and periods of gloomy silence and depression alternated with energetic, exuberant outbursts. The letters provided Voskuil with the perfect opportunity to illustrate how Breugelman’s situation deteriorated and the chaos in his head worsened. In an interview, the author remarked, ‘The reader has to be confronted with that mania, he should feel crushed’.

The friendship between the two men was also crushed in reality. Not only because Breugelman’s political views changed radically from extreme left to extreme right, but primarily due to the fact that Breugelman refused to do anything to combat his progressive illness. In the last chapter he stops taking his medicine and ends up languishing in a mental institution. Just how ill his friend is seems not to really dawn on Voskuil even then. Finally, he is rudely awakened on the very last page, when Breugelman sends him and his wife packing for good: ‘Sod bloody off!’

The poignant final scene of a moody, honest and authentic book.

In addition to large chunks of correspondence, Voskuil also makes use of numerous other forms for this portrait: descriptions of their meetings, their walks, their conversations; brief, revealing and often funny anecdotes. The passages in which he portrays the manic Breugelman in word and gesture are a masterpiece. It is the very diversity of these forms that makes this requiem such a lively book. - Het Parool

Voskuil has succeeded in raising this autobiographical material above the personal. - Het Parool

Vintage Voskuil in particular are the absurdist dialogues about everything from Multatuli to smoked sausages, the condemnatory asides and the scenes in which the fiasco of human communication is illustrated in an almost slapstick manner. - NRC Handelsblad

Portretten en herinneringen, luidt de ondertitel op het omslag van Onder andere. Het is van alles wat, een staalkaart van wat zijn werk te bieden heeft: rake portretten, observaties, uitdijende beschrijvingen van contacten met vrienden, verslagen van zijn fietstochten. En wat betreft is het boek geschikt als eerste kennismaking met deze bijzondere auteur.

http://www.letterenfonds.nl/en/author/194/jj-voskuil

The same theme returns, essentially, in his latest book, Requiem for a Friend. The story of the friendship between Han Voskuil and Jan Breugelman, two boys from the Hague who grow up together and maintain a stormy relationship in later life through letters and meetings, also finishes in deception. There is, nevertheless, one big difference. Unlike Voskuil’s earlier work, here the major characters appear under their own name (only Breugelman’s has been altered slightly for reasons of privacy) and the book is written in the first person.

Voskuil evidently wished to make his new novel more personal than his previous books. More authentic. The effect is enhanced by the continual quotes from the letters written to him by Jan Breugelman in the course of their friendship. Breugelman was a manic depressive and periods of gloomy silence and depression alternated with energetic, exuberant outbursts. The letters provided Voskuil with the perfect opportunity to illustrate how Breugelman’s situation deteriorated and the chaos in his head worsened. In an interview, the author remarked, ‘The reader has to be confronted with that mania, he should feel crushed’.

The friendship between the two men was also crushed in reality. Not only because Breugelman’s political views changed radically from extreme left to extreme right, but primarily due to the fact that Breugelman refused to do anything to combat his progressive illness. In the last chapter he stops taking his medicine and ends up languishing in a mental institution. Just how ill his friend is seems not to really dawn on Voskuil even then. Finally, he is rudely awakened on the very last page, when Breugelman sends him and his wife packing for good: ‘Sod bloody off!’

The poignant final scene of a moody, honest and authentic book.

In addition to large chunks of correspondence, Voskuil also makes use of numerous other forms for this portrait: descriptions of their meetings, their walks, their conversations; brief, revealing and often funny anecdotes. The passages in which he portrays the manic Breugelman in word and gesture are a masterpiece. It is the very diversity of these forms that makes this requiem such a lively book. - Het Parool

Voskuil has succeeded in raising this autobiographical material above the personal. - Het Parool

Vintage Voskuil in particular are the absurdist dialogues about everything from Multatuli to smoked sausages, the condemnatory asides and the scenes in which the fiasco of human communication is illustrated in an almost slapstick manner. - NRC Handelsblad

Portretten en herinneringen, luidt de ondertitel op het omslag van Onder andere. Het is van alles wat, een staalkaart van wat zijn werk te bieden heeft: rake portretten, observaties, uitdijende beschrijvingen van contacten met vrienden, verslagen van zijn fietstochten. En wat betreft is het boek geschikt als eerste kennismaking met deze bijzondere auteur.

Voskuil is op zijn best als scherp waarnemer met een onderkoeld gevoel voor humor. Vooral het stuk over het wonen in de Jordaan, toen nog een rauwe Amsterdamse volksbuurt, toont dat weer aan. Hilarisch is de scène waarin de totaal beschonken bovenbuurman na een enorme ruzie met de buurvrouw eerst in de gracht springt en vervolgens weer naar boven gehesen uit het raam springt. ’s Morgens vroeg wordt er gebeld. “De stem van Nel: ‘Wat mot u?’ Die leefde dus nog.”

In het stuk over zijn socialistische jeugd krijgen we een bijzondere inkijk in de jeugd van de auteur - inclusief een beeld van de oorlogsjaren in Den Haag waar schooljongens meehielpen een tankwal op te werpen. Zijn vader, Klaas Voskuil, vooraanstaand socialist en journalist, had het in de oorlog niet gemakkelijk. Hij kromp in de ogen van zijn zoon, maar tegelijkertijd bracht de oorlog ze ook nader. Meesterlijk is de laatste scène. Vader vertelt dat ze na de oorlog wellicht naar Amsterdam zullen verhuizen. ‘Vind je het leuk? Vroeg ik. - ‘Ik heb het hier altijd naar mijn zin gehad’, zei hij ontwijkend. Plotseling ging hij in looppas over. Ik volgde hem en bijna tegelijk begonnen we te zingen, terwijl hij zijn knieën hoog optilde: ‘(…)’ dan gaan we schrij-ven en dan gaan we schrij-ven.’

‘He was in a quandary right to the end,’ writes Lousje Voskuil-Haspers in the foreword to Inside the Skin, ‘because of the intimate nature of the book and his not wanting to hurt anyone.’ The author, who died last year, had misgivings about publication and left the final decision to his wife. It is hardly surprising that Voskuil had his doubts or that his wife could not easily decide what to do, since Inside the Skin is a remarkable account of the emotional roller-coaster the author finds himself on when he falls in love with his best friend’s wife. There can be few books in world literature that expose so inexorably the contradictions in the author’s own attitude and feelings. The central character wants to be consistent but is tossed back and forth by his emotions. All this against the background of a 1950s intellectual milieu in which opposition to bourgeois morality appears to be the most important of values.

In het stuk over zijn socialistische jeugd krijgen we een bijzondere inkijk in de jeugd van de auteur - inclusief een beeld van de oorlogsjaren in Den Haag waar schooljongens meehielpen een tankwal op te werpen. Zijn vader, Klaas Voskuil, vooraanstaand socialist en journalist, had het in de oorlog niet gemakkelijk. Hij kromp in de ogen van zijn zoon, maar tegelijkertijd bracht de oorlog ze ook nader. Meesterlijk is de laatste scène. Vader vertelt dat ze na de oorlog wellicht naar Amsterdam zullen verhuizen. ‘Vind je het leuk? Vroeg ik. - ‘Ik heb het hier altijd naar mijn zin gehad’, zei hij ontwijkend. Plotseling ging hij in looppas over. Ik volgde hem en bijna tegelijk begonnen we te zingen, terwijl hij zijn knieën hoog optilde: ‘(…)’ dan gaan we schrij-ven en dan gaan we schrij-ven.’

‘He was in a quandary right to the end,’ writes Lousje Voskuil-Haspers in the foreword to Inside the Skin, ‘because of the intimate nature of the book and his not wanting to hurt anyone.’ The author, who died last year, had misgivings about publication and left the final decision to his wife. It is hardly surprising that Voskuil had his doubts or that his wife could not easily decide what to do, since Inside the Skin is a remarkable account of the emotional roller-coaster the author finds himself on when he falls in love with his best friend’s wife. There can be few books in world literature that expose so inexorably the contradictions in the author’s own attitude and feelings. The central character wants to be consistent but is tossed back and forth by his emotions. All this against the background of a 1950s intellectual milieu in which opposition to bourgeois morality appears to be the most important of values.

At the start of the novel Maarten is confronted by his friend Paul’s apparently untroubled decision to live a ‘bourgeois life’. Paul has become a teacher in a provincial town, with a modern house and a child on the way. Maarten and Nicolien resent the fact that he now lives as he does, despite all his talk about ‘resistance’ and ‘Paris’. Nevertheless, Maarten too baulks at following their mutual friend Henriette, who has taken the plunge and moved to Paris. He knows that in the end he will ‘capitulate’ and seek a career. The thing he holds against Paul most of all is his refusal to acknowledge his ‘cowardice’.

Against this background, Maarten falls in love with Paul’s wife Rosalie. It is fascinating to watch how at first Rosalie chiefly annoys him (Maarten and Nicolien see her as the evil genius behind Paul’s bourgeois existence), until he falls for her charms. He wrestles with concepts like loyalty (‘nothing but cowardice’) and longs to act alone, to be tough, a ‘plebeian’, a ‘commercial traveller’ (the opposite of the intellectual in this milieu), but of course an inhibited intellectual is what he remains.

Voskuil’s technique, as in his other novels, is to report events, conversations and reactions with great precision. One significant difference between this and the author’s other novels is that Inside the Skin is written in the first person, making it seem closer both to the author and to the reader. It is a painful account, in which the author spares neither himself nor his wife and friends, making his wife’s decision to publish particularly courageous.

A merciless self-analysis and an indirect but rigorous settling of accounts. - Nederlands Dagblad

A disillusioning look at the constancy of the supposedly deeper things in life, such as emotions, feelings and passionate desires. - De Groene Amsterdammer

The things that remain valuable in this posthumous confession are reminiscent of the pent-up rage with which W.F. Hermans attacked bourgeois morality in books such as Acacia’s Tears, I’m Always Right and Paranoia, and the grim analysis offered by existentialist authors like Camus and Sartre who were so popular in the 1950s. - Trouw

A rich psychological sketch of a man who, one last time, against his better judgment, tries to break out of the constraining skin of the little man. - HP / De Tijd

Against this background, Maarten falls in love with Paul’s wife Rosalie. It is fascinating to watch how at first Rosalie chiefly annoys him (Maarten and Nicolien see her as the evil genius behind Paul’s bourgeois existence), until he falls for her charms. He wrestles with concepts like loyalty (‘nothing but cowardice’) and longs to act alone, to be tough, a ‘plebeian’, a ‘commercial traveller’ (the opposite of the intellectual in this milieu), but of course an inhibited intellectual is what he remains.

Voskuil’s technique, as in his other novels, is to report events, conversations and reactions with great precision. One significant difference between this and the author’s other novels is that Inside the Skin is written in the first person, making it seem closer both to the author and to the reader. It is a painful account, in which the author spares neither himself nor his wife and friends, making his wife’s decision to publish particularly courageous.

A merciless self-analysis and an indirect but rigorous settling of accounts. - Nederlands Dagblad

A disillusioning look at the constancy of the supposedly deeper things in life, such as emotions, feelings and passionate desires. - De Groene Amsterdammer

The things that remain valuable in this posthumous confession are reminiscent of the pent-up rage with which W.F. Hermans attacked bourgeois morality in books such as Acacia’s Tears, I’m Always Right and Paranoia, and the grim analysis offered by existentialist authors like Camus and Sartre who were so popular in the 1950s. - Trouw

A rich psychological sketch of a man who, one last time, against his better judgment, tries to break out of the constraining skin of the little man. - HP / De Tijd

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.