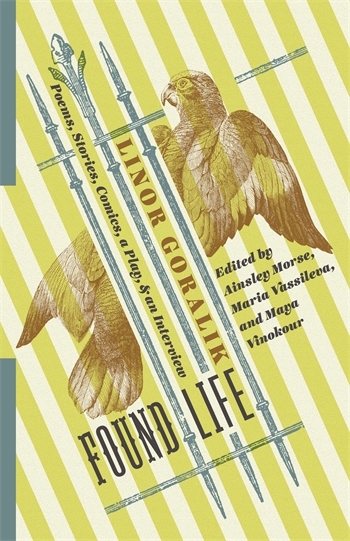

Linor Goralik, Found Life : Poems, Stories, Comics, a Play, and an Interview, Ed. by Ainsley Morse, Maria Vassileva, and Maya Vinokour. Columbia University Press, 2017.

excerpts

One of the first Russian writers to make a name for herself on the Internet, Linor Goralik writes conversational short works that conjure the absurd in all its forms, reflecting post-Soviet life and daily universals. Her mastery of the minimal, including a wide range of experiments in different forms of micro-prose, is on full display in this collection of poems, stories, comics, a play, and an interview, here translated for the first time. In Found Life, speech, condensed to the extreme, captures a vivid picture of fleeting interactions in a quickly moving world. Goralik's works evoke an unconventional palette of moods and atmospheres-slight doubt, subtle sadness, vague unease-through accumulation of unexpected details and command over colloquial language. While calling up a range of voices, her works are marked by a distinct voice, simultaneously slightly naive and deeply ironic. She is a keen observer of the female condition, recounting gendered tribulations with awareness and amusement. From spiritual rabbits and biblical zoos to poems about loss and comics about poetry, Goralik's colorful language and pervasive dark comedy capture the heights of absurdity and depths of grief.

Linor Goralik is a Renaissance woman of our own day, writing (and drawing!) in a wide range of genres, all with sharp intelligence. Her writing is fresh and thought-provoking, with both profound insight and deadpan humor. The numerous translators allow exploration of different aspects of Goralik’s voice, so that this selection of work offers the reader a wonderful variety and versatility. A beautiful and important book! - Sibelan Forrester

Linor Goralik has a perfect ear for the wander and wonder of ordinary speech, for the way the weirdness of human language conveys the weirdness of human experience. In turn hilarious and heart-rending, her fictions and poems bristle with epiphanies, with jolts of comprehension and, just as commonly, of vertiginous incomprehension. A literary descendant of Daniil Kharms, the conceptualists, and Chekhov, this transnational writer-ventriloquist describes a world of multiple realities, including that of the supernatural, but she is also painstakingly precise in her depictions of male and female behavior in post-Soviet space. The editors and translators are to be praised for, among many other things, finding the idiomatic and colloquial American English to convincingly express the alive Russian of the original. - Eugene Ostashevsky

Quietly subversive works of imagination from a Ukraine-born Russian/Israeli writer who describes herself as an essayist.

In Putin’s Russia, is there such a thing as a Valley girl? To judge by some of the aperçus in this collection by pop-culture phenom Goralik, we might conclude that indeed there is: "How old is he? Probably pushing fifty. Gray hair, I always loved that type. You know, he did ballet as a kid, then worked for the KGB, so, like, basically a real inspired dude.” Well into her 40s, though, Goralik mostly writes with a mature distance. One story, in its entirety, is a flash-fiction masterpiece: "The wife comes home and the cat smells like someone else’s perfume.” It’s a few words more than Hemingway spent on baby shoes, but it’s a compressed gem all the same. Often as gritty as a Brassaï photograph, Goralik’s sketches, some originally published on the Web, center on ordinary scenes: American tourists gawk before the Kremlin, an Easter card curdles in a puddle of mud, a battered woman puts on makeup in a restaurant, unselfconscious and apparently unshaken. At times Goralik drifts into dreams—as with one fellow who, in the nightmare of missing a long-ago exam, discovers that he can no longer remember the Russian of the Soviet era—but seldom indulges in surrealism; her work is notable for its matter-of-factness, no matter how absurd the scenario. This anthology gathers work from across several genres, from those short works to some longer pieces such as the Bulgakov-worthy story “Agatha Goes Home” and the novella Valerii, as well as poems, plays, and even a sequence of cartoons that are somewhat reminiscent of Chris Ware’s, if much darker: in one, a bunny lists off all the vices he doesn’t indulge in, from smoking to drinking and gambling, “because all that might distract me from important suicidal thoughts.”

A welcome collection from a writer worth hearing more from—so translators, get busy. - Kirkus Reviews

Russian-Israeli writer, poet, playwright, and installation artist Linor Goralik first entered the literary scene around 2001 as a prolific LiveJournal poster. A workaholic founder of new-media discourses, she soon became a fixture of the early Russian-language Internet. Perhaps because it originated in the blogosphere, Goralik’s writing often seems aimed at a narrow circle of insiders—an impression fostered by the remarkable intimacy of her style and her excellent eye for detail. This last quality enables Goralik to be political without veering into preachiness or polemic. For example, her ongoing “Five stories about…” series presents topical vignettes from the life of Russia’s liberal intelligentsia that, at first glance, seem entirely divorced from politics. Identified only by their white-collar professions and a single initial, Goralik’s characters are shown simply moving through life: going through passport control, dealing with a mole infestation at the dacha, or declining a favorite nephew’s request to photograph his upcoming orgy. For all their understated irony, these little fables often end with a devastating twist. Each one begins with a mock-hypothetical “So, let’s say…” followed by an anecdote of such lapidary specificity that it seems drawn from directly observed reality. One entry from April 2014 reads:

So, let’s say classics professor S. tells her students that, when considering the culture of the Roman Empire, it’s important to note how small the number of truly educated people really was. And that the entire intellectual elite of Caesar’s time could have fit into two to three paddy wagons.

What is this story about? The words “let’s say” recall the beginning of a mathematical proof, suggesting we’re about to witness the impartial demonstration of a general principle. The next line only intensifies this impression with its neutral invocations of the nearly nameless “classics professor” and the cultural values of ancient Rome. But the final sentence—specifically, the reference to “paddy wagons,” which police have been stuffing full of protesters since the “Snow Revolution” of 2011–12—makes it clear that S. can only be a Russian intellectual speaking to a group of like-minded peers. Slow-burn syllogisms like this one belie Goralik’s claim that she doesn’t “give a shit” about politics, as she told journalist Yulia Idlis in 2010.

Much of Goralik’s work, including the pieces below, relies on this kind of reversal. After carefully constructing the illusion of sober abstraction, she tops it with a detail that brings the entire structure tumbling down to earth. Sometimes this detail acts as a punchline (as in the cartoon, here, from the Bunnypuss strip); at other times, it is more like a Chekhovian pointe, requiring several lines, paragraphs, or pages to emerge. Even as Goralik addresses topics specific to the contemporary Russian context, such as the effects of Western sanctions or the lingering traumas of Stalinism, she also pushes universal emotional buttons. Sudden sartorial upsets, a snub from a colleague, a misinterpreted remark: Goralik excels in wresting these small moments from a sea of higher-profile troubles.

Just as we can discern the ancestors of the novel—the letter and the diary—in eighteenth-century exemplars of the genre, so too does Goralik’s writing betray its roots in the anarchic, confessional culture of early Runet. Even on paper, Goralik’s texts retain an intimacy and immediacy, a sense of just having been overheard, that digital natives associate with online posting. They are also eminently shareable, which is what compelled me to translate them in the first place—so I could keep on laughing and cringing, this time with English-speaking friends. Maya Vinokour http://www.musicandliterature.org/features/2017/11/3/the-poetry-of-linor-goralik

One of the first Russian writers to make a name for herself on the Internet, Linor Goralik writes conversational short works that conjure the absurd in all its forms, reflecting post-Soviet life and daily universals. Her mastery of the minimal, including a wide range of experiments in different forms of micro-prose, is on full display in this collection of poems, stories, comics, a play, and an interview, here translated for the first time. In Found Life, speech, condensed to the extreme, captures a vivid picture of fleeting interactions in a quickly moving world. Goralik's works evoke an unconventional palette of moods and atmospheres-slight doubt, subtle sadness, vague unease-through accumulation of unexpected details and command over colloquial language. While calling up a range of voices, her works are marked by a distinct voice, simultaneously slightly naive and deeply ironic. She is a keen observer of the female condition, recounting gendered tribulations with awareness and amusement. From spiritual rabbits and biblical zoos to poems about loss and comics about poetry, Goralik's colorful language and pervasive dark comedy capture the heights of absurdity and depths of grief.

Linor Goralik is a Renaissance woman of our own day, writing (and drawing!) in a wide range of genres, all with sharp intelligence. Her writing is fresh and thought-provoking, with both profound insight and deadpan humor. The numerous translators allow exploration of different aspects of Goralik’s voice, so that this selection of work offers the reader a wonderful variety and versatility. A beautiful and important book! - Sibelan Forrester

Linor Goralik has a perfect ear for the wander and wonder of ordinary speech, for the way the weirdness of human language conveys the weirdness of human experience. In turn hilarious and heart-rending, her fictions and poems bristle with epiphanies, with jolts of comprehension and, just as commonly, of vertiginous incomprehension. A literary descendant of Daniil Kharms, the conceptualists, and Chekhov, this transnational writer-ventriloquist describes a world of multiple realities, including that of the supernatural, but she is also painstakingly precise in her depictions of male and female behavior in post-Soviet space. The editors and translators are to be praised for, among many other things, finding the idiomatic and colloquial American English to convincingly express the alive Russian of the original. - Eugene Ostashevsky

Quietly subversive works of imagination from a Ukraine-born Russian/Israeli writer who describes herself as an essayist.

In Putin’s Russia, is there such a thing as a Valley girl? To judge by some of the aperçus in this collection by pop-culture phenom Goralik, we might conclude that indeed there is: "How old is he? Probably pushing fifty. Gray hair, I always loved that type. You know, he did ballet as a kid, then worked for the KGB, so, like, basically a real inspired dude.” Well into her 40s, though, Goralik mostly writes with a mature distance. One story, in its entirety, is a flash-fiction masterpiece: "The wife comes home and the cat smells like someone else’s perfume.” It’s a few words more than Hemingway spent on baby shoes, but it’s a compressed gem all the same. Often as gritty as a Brassaï photograph, Goralik’s sketches, some originally published on the Web, center on ordinary scenes: American tourists gawk before the Kremlin, an Easter card curdles in a puddle of mud, a battered woman puts on makeup in a restaurant, unselfconscious and apparently unshaken. At times Goralik drifts into dreams—as with one fellow who, in the nightmare of missing a long-ago exam, discovers that he can no longer remember the Russian of the Soviet era—but seldom indulges in surrealism; her work is notable for its matter-of-factness, no matter how absurd the scenario. This anthology gathers work from across several genres, from those short works to some longer pieces such as the Bulgakov-worthy story “Agatha Goes Home” and the novella Valerii, as well as poems, plays, and even a sequence of cartoons that are somewhat reminiscent of Chris Ware’s, if much darker: in one, a bunny lists off all the vices he doesn’t indulge in, from smoking to drinking and gambling, “because all that might distract me from important suicidal thoughts.”

A welcome collection from a writer worth hearing more from—so translators, get busy. - Kirkus Reviews

Russian-Israeli writer, poet, playwright, and installation artist Linor Goralik first entered the literary scene around 2001 as a prolific LiveJournal poster. A workaholic founder of new-media discourses, she soon became a fixture of the early Russian-language Internet. Perhaps because it originated in the blogosphere, Goralik’s writing often seems aimed at a narrow circle of insiders—an impression fostered by the remarkable intimacy of her style and her excellent eye for detail. This last quality enables Goralik to be political without veering into preachiness or polemic. For example, her ongoing “Five stories about…” series presents topical vignettes from the life of Russia’s liberal intelligentsia that, at first glance, seem entirely divorced from politics. Identified only by their white-collar professions and a single initial, Goralik’s characters are shown simply moving through life: going through passport control, dealing with a mole infestation at the dacha, or declining a favorite nephew’s request to photograph his upcoming orgy. For all their understated irony, these little fables often end with a devastating twist. Each one begins with a mock-hypothetical “So, let’s say…” followed by an anecdote of such lapidary specificity that it seems drawn from directly observed reality. One entry from April 2014 reads:

So, let’s say classics professor S. tells her students that, when considering the culture of the Roman Empire, it’s important to note how small the number of truly educated people really was. And that the entire intellectual elite of Caesar’s time could have fit into two to three paddy wagons.

What is this story about? The words “let’s say” recall the beginning of a mathematical proof, suggesting we’re about to witness the impartial demonstration of a general principle. The next line only intensifies this impression with its neutral invocations of the nearly nameless “classics professor” and the cultural values of ancient Rome. But the final sentence—specifically, the reference to “paddy wagons,” which police have been stuffing full of protesters since the “Snow Revolution” of 2011–12—makes it clear that S. can only be a Russian intellectual speaking to a group of like-minded peers. Slow-burn syllogisms like this one belie Goralik’s claim that she doesn’t “give a shit” about politics, as she told journalist Yulia Idlis in 2010.

Much of Goralik’s work, including the pieces below, relies on this kind of reversal. After carefully constructing the illusion of sober abstraction, she tops it with a detail that brings the entire structure tumbling down to earth. Sometimes this detail acts as a punchline (as in the cartoon, here, from the Bunnypuss strip); at other times, it is more like a Chekhovian pointe, requiring several lines, paragraphs, or pages to emerge. Even as Goralik addresses topics specific to the contemporary Russian context, such as the effects of Western sanctions or the lingering traumas of Stalinism, she also pushes universal emotional buttons. Sudden sartorial upsets, a snub from a colleague, a misinterpreted remark: Goralik excels in wresting these small moments from a sea of higher-profile troubles.

Just as we can discern the ancestors of the novel—the letter and the diary—in eighteenth-century exemplars of the genre, so too does Goralik’s writing betray its roots in the anarchic, confessional culture of early Runet. Even on paper, Goralik’s texts retain an intimacy and immediacy, a sense of just having been overheard, that digital natives associate with online posting. They are also eminently shareable, which is what compelled me to translate them in the first place—so I could keep on laughing and cringing, this time with English-speaking friends. Maya Vinokour http://www.musicandliterature.org/features/2017/11/3/the-poetry-of-linor-goralik

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.