Eça de Queirós, The Illustrious House of Ramires. Trans. by Margaret Jull Costa, New Directions, 2017.

The Illustrious House of Ramires, presented here in a sparkling new translation by Margaret Jull Costa, is the favorite novel of many Eça de Queirós aficionados. This late masterpiece, wickedly funny and yet profoundly tender, centers on Gonçalo Ramires, heir to a family so aristocratic that it predates even the kings of Portugal. Gonçalo―charming but disastrously effete, idealistic but hopelessly weak―muddles through his pampered life, burdened by a grand ambition. He is determined to write a great historical novel based on the heroic deeds of his fierce medieval ancestors. But “the record of their valor,” as The London Spectator remarked, “is ironically counterpointed by his own chicanery. A combination of Don Quixote and Walter Mitty, Ramires is continually humiliated but at the same time kindhearted. Ironic comedy is the keynote of the novel. Eça de Queirós has justly been compared with Flaubert and Stendhal."

“Eça de Queirós ought to be up there with Balzac, Dickens, and Tolstoy as one of the talismanic names of the nineteenth century.”- London Observer

“A writer of mesmerizing literary power. We should be grateful for such blessings.”- Michael Dirda,

“A writer of genius.”- Harold Bloom

“Eça de Queirós was a god, and this is a translation by another deity (Margaret Jull Costa), so make sure to take a look.”- Scott Esposito

“His excellent prose glides through real experience and private dream in a manner that is leading on toward the achievements of Proust.”- V. S. Pritchett

Slyly funny and richly detailed, this reissue of Quieros's long out-of-print book makes for a delicious introduction to Portugal's greatest novelist. First published in 1900, the year of Quieros's death, it portrays Goncalo Mendes Ramires, the latest in an aristocratic family that predates even the kings of Portugal. In the isolation of the gloomy ancient tower of Santa Ireneia, Goncalo rehearses the feats of derring-do of an uninterrupted line of ancestors whose most recent contribution is himself, ``a graduate who had failed his third year examinations at university.'' Hoping to win some small scholarly reputation and thus secure a political future in the capital, Goncalo sets out to portray (a la Walter Scott), the adventures of one such ancestor. Installments recording the haughty courage and cruelty of his medieval forefather, Tructesindo Ramires, contrast with Goncalo's rather banausic existence, his cowardice, his small acts of noblesse oblige and his questionable apotheosis. Quieros's luxurious prose lends itself well to both the subtle irony of his morality play and the beauty of a decrepit Portuguese estate with its autumn sun, wilting flowers, faded portraits and other reminders of a bloody and powerful past. - Publishers Weekly

Late, reflective work by de Queirós (1845-1900), widely considered Portugal’s greatest novelist.

Writing at the height of Portugal’s overseas empire, de Queirós traces the life of a man who is a touch too proud of his ancestors, so much so that he reminds an emissary of the king himself, “My ancestors had a house in Treixedo long before there were any kings of Portugal, long before there was a Portugal.” By the end of the book, we are given to understand that Gonçalo Mendes Ramires, who quixotically likes to call himself the Nobleman of the Tower, is himself a metonym for the Portuguese nation in all its bumbling glory: “His generosity, his thoughtlessness, his chaotic business dealings, his truly honorable feelings, his scruples, which can seem almost childish”—and that’s to say nothing of a certain shlemielishness that doesn’t quite hold up well by comparison to the illustrious ancestors he reminds himself of daily, enshrined in the portraits and books with which Gonçalo surrounds himself in his teetering family home. He’s a bit more self-aware than Cervantes’ great hero, but we are assured that Gonçalo, however much he might like to have fought along his ancestor Tructesindo, would not have fit in well. Still, Gonçalo manages to make something of himself as the story spins out, having gone from callous reactionary to somewhat technocratic African colonialist and having finally finished the long book about his noble house that occupies much of his waking time. This is very much a 19th-century novel, unhurried and richly observed; while it can be a little fusty, de Queirós, who has been likened to Flaubert, turns in elegantly poetic prose: “When I was fighting the Moors, a physician once told me that a woman is like a soothing, scented breeze, but one that leaves everything tangled and confused.”

A touch long but with never a wasted word. Fans of Vargas Llosa and Saramago will find a kindred spirit in these pages. - Kirkus

The Portuguese novel The Maias appeared in 1888, when its author, José Maria de Eça de Queirós (1845-1900), was forty-three years old. Eça had spent close to a decade working on the book—which he initially planned as the first entry in a series called “Scenes from Portuguese Life”—during his diplomatic service in England. The novel’s story involves three generations of an illustrious noble family, which by the 1870s has been reduced to the white-haired Afonso da Maia (“a man from another era, austere and pure”) and his singularly charmed and charming grandson Carlos. A Lisbon doctor with intellectual ambitions, Carlos is also adept with a sword and possesses “precisely the correct number of enemies required to confirm his superiority.”

The plot of The Maias turns on a forbidden love affair of Carlos’s and its consequences. But outlining these does little to account for the book’s exalted status among its admirers—why José Saramago called it “the greatest book by Portugal’s greatest novelist,” for example, or why V.S. Pritchett, writing in The New York Review in 1970, wrote that Eça’s novels pointed “toward the achievements of Proust.” It’s tempting to single out its fine quality of description, brilliant dialogue, rich cast of secondary characters, and unusual irony, which combines biting misanthropy with a broad and flexible attention to human pain. For my part—and I am, admittedly, reading in translation—another aspect of Eça’s writing has to be mentioned: how time unfolds in the book, with a sublime, almost arboreal leisure.

Eça’s numerous fictions have a central place in Portuguese and Brazilian literature, but they don’t seem much read elsewhere—at least not these days. Abroad, he is often cast as an overlooked equal to the great nineteenth-century European realists. That comparison is not illogical: his sexually provocative and socially scathing early novels, which dealt with love affairs and scandals among the clergy and the well-off middle class, were heralded for introducing realism to Portugal. These works not only mention certain of their inspirations, such as Balzac, but pay clear tribute to them—Flaubert above all—in the details of their plots. (Luísa, for instance, the stifled and daydreaming wife in Eça’s 1878 Cousin Bazilio, can’t help but evoke Emma Bovary.) At the same time, critics have often been at odds in characterizing Eça: asking if he is patriotic or subversive, or whether the answer to that question changed over the course of his career; how much of the Romantic colors his sense of “reality”; and whether he wouldn’t more profitably be understood as a kind of camouflaged avant-garde writer. What all these conflicting accounts confirm is the beguiling elusiveness of the Lusitanian’s work.

Eça established his reputation with his tense and claustrophobic first novel, The Crime of Father Amaro. It is a debut that’s also not one: it was twice seriously revised after publication. (Among other changes, the third edition is almost five times as long as the first.) The novel was initially released in 1875 without Eça’s knowledge or approval after he had given it to an editor friend with the understanding that it was still at an early stage; he made substantial changes to the next published text. The second revision, in 1880, was to improve on aspects of the book with the novelistic maturity five more years had lent. This is the edition that’s commonly read now.

It tells a story of country-town scandal about a sensitive local beauty (Amélia) and the new priest of the title, initially a boarder at her seamstress mother’s house. The romance is beset with difficulties: as well as the mother, there’s a domestic staff and a legitimate young suitor for Amélia to mind, and the town’s other priests are often around, arguing, plotting, gossiping, and, wherever possible, eating and drinking. Chief among the book’s quirks is Eça’s oddly malleable sense of character; the novel seems to stand at a strange juncture between realism, fantasy, and the philosophical conte. Amaro’s backstory is cursory and not quite convincing enough to explain the extreme change he undergoes over the course of the novel; Amelia, for her part, suffers a fever that seems something other than medical. Yet reservations like these fall away in light of Eça’s acute and uncannily limber sense of his characters’ psychology from moment to moment, and his genius for surfaces and physical detail. Meeting at one point, the pent-up lovers rush to clasp hands “from the wrists to the elbow.” Throughout his work, Eça’s rapid and clear descriptions make fleeting characters lodge in the mind: it might be someone whose jacket is held together with a pin, a mother nursing a coughing baby, a farmer with hands that look like roots, or an irritable hunchback who “deliberately kept his nicotine-stained fingernails long” so as better to play the guitar.

Although sometimes discounted for its comparatively lower stakes, his second novel, Cousin Bazilio, a flirtation with Madame Bovary that simultaneously reproduces much of the layout from Father Amaro, offers a new and entertaining brio. (It’s the first nineteenth-century novel this reader has encountered in which two female friends roll around laughing after one has fended off a man by striking him with his own walking stick.) It did well for its sensational subject—adulterous bourgeois seduction—but was criticized, along with Father Amaro, by a promising young Brazilian critic: in two articles, Machado de Assis acknowledged the author’s gifts but objected to the books’ explicit sensuality and a few other strange things, including a “photographic” brand of prolix realism that arguably applied little to these works.

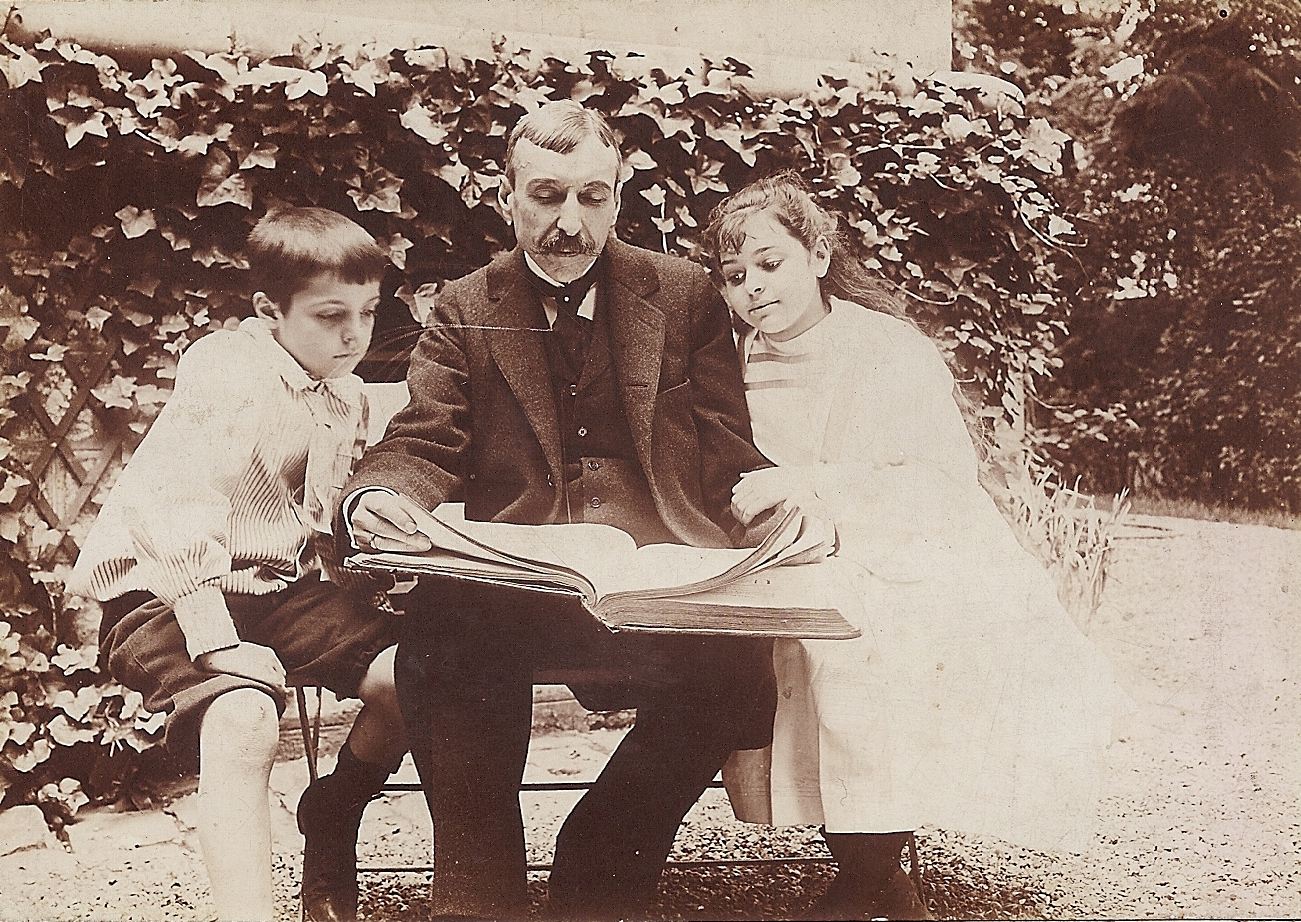

Eça de Queirós was an illegitimate child brought up by his paternal grandparents, who lived in a small coastal town called Verdemilho and sent him to school in Oporto. His parents finally married, but even then he didn’t join them. He studied law but never practiced—his novels, it’s hard not to notice, are full of people not following through. Since literary careers at any level were precarious, at his father’s urging Eça eventually joined the consular service. His posts included Havana, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Bristol, where he stayed for nine years, and finally a short stint in Paris, where the former Francophile had surprisingly little contact with other writers. Retrospectively included as part of Portugal’s reform-minded “Generation of the Seventies”—with friends such as the influential historian Oliveira Martins and the poet Antero de Quental—Eça appears not to have minded irritating a host nation when he saw the need. In Cuba, he continued advocacy efforts for exploited Chinese plantation workers; from England he wrote articles for a paper back home (a few samples appear in the out-of-print Letters from England), some of them lengthily dissecting British misjudgment and aggression in Ireland and the Middle East.

Eça’s books are quite specifically about Portugal, and at a particular moment. The country in which he came of age didn’t have much in common with France or England, nor did it much resemble the maritime and trade power Portugal itself had been three centuries before. A character returning from abroad in The Maias observes how “the same guard patrolled sleepily round and round the sad statue of Camões,” embodying this changed fortune. At the end of the nineteenth century, Portugal’s system of agriculture was still close to feudal. The population—Roman Catholic, widely illiterate, and ruled by an inert constitutional monarchy—had been depleted by emigration to Brazil, a former colony that had been independent since 1822. At the same time, Lisbon housed a sophisticated elite, and university life at Coimbra was notably fermented in Eça’s generation by an influx of European texts, culture, and liberal social ideas. This curious entanglement of classes and values strongly informed Eça’s novels, although the Portugal of his imagination could lag behind reality. (The books depict a place only lightly grazed by the Industrial Revolution, perhaps never to meet the twentieth century, while the actual nation had begun a major public works program, including extensive road and railway systems, while Eça was still a child, and machine production was to pick up significantly in the following decades.)

A number of Eça’s opinionated talkers are acidly critical of the country as a whole, while also a bit melancholy about the contrast between its current situation and the old Portugal of seafaring discovery and glory. A dandy in Cousin Bazilio, talking of his homeland, asks God for a cleansing earthquake, “vaguely grateful to a nation whose defects supplied him with so much material for his jibes.” That Lisbon had lost tens of thousands in the great earthquake of 1755 lends the glib cynicism here an added hint of cruelty.

The upper-class men in these novels occasionally challenge each other to duels, and talk with conspicuous frequency of wanting to “thrash” one another. Those, at least, are the words they use in the English of Margaret Jull Costa, Eça’s frequent, highly regarded current translator. “The animal ought to be put down. It’s a moral duty, a question of public hygiene and good taste, to do away with that ball of human slime,” says Carlos da Maia’s best friend about an absurd and conniving flatterer in their circle. (As is often the case in Eça, there are nonetheless times where you can feel this man’s self-inflicted suffering.)

The poor in his books can be poor indeed, without even the illusion of upward mobility, given to illness, and encouraged by the church to accept their lot as a sign of Christian virtue. Conversation can be blatantly sexist (as, very occasionally, can be the narrative voice itself) and harsh nicknames are normal. Women risk disaster if they get involved with men; at the very least, as the seducer Bazilio says in the novel that bears his name, “A woman who runs away ceases to be Senhora Dona So-and-so and becomes plain So-and-so, that woman who ran away, that hussy, someone or other’s mistress!”

For a range of reasons, there are several posthumous Eça books. The brisk and charming novella The Yellow Sofa—reissued by New Directions last year in a translation by John Vetch—was one of three manuscripts discovered in a box by the author’s son, without accompanying information. According to Maria Filomena Mónica, Eça’s thorough biographer, the text, quite possibly unrevised, was edited by the writer’s eldest son more freely than he acknowledged—even so, it’s a good introduction to Eça’s sensibility, naturally fusing as it does two of the main tones between which he moved: one more realist in style, the other more wholly comic.

The Yellow Sofa begins on the day of the forgotten fourth wedding anniversary of a somewhat dull Lisbon importer named Godofredo Alves, who comes home to find his wife with a man: his elegant and younger business partner, Machado, who has also been a longtime family friend. Both his wife and Machado claim it was the first time, inexplicably laughing off some found, beribboned correspondence between the pair as a joke. It’s characteristic of Eça’s humor that much of what follows is taken up by the anticipation of a duel that never occurs, and also revealing about his irreverence and irony that the kernel of the book should be an illicit affair: “He seemed to see throughout the city a sarabande of lovers and husbands, some of them escaping, husbands pursuing them, a hide-and-seek of men chasing each other around women’s skirts!” In varying configurations and among all social classes, this game of hide-and-seek is played out across Eça’s work.

The final book Eça wrote, The Illustrious House of Ramires, has just come out in a much-needed new translation by Jull Costa. Gonçalo Mendes Ramires, the main character, is a familiar Eça type—a well-meaning yet weak-willed aristocrat, this time one whose family is so rarefied and woven into national lore that he is often referred to in the book simply as “The Nobleman.” (After his marriage to Emília de Castro Pamplona Resende in 1886, Eça had begun to encounter some of Portugal’s most prominent aristocratic families.) A bachelor with beautiful estates and a thousand-year-old tower, Gonçalo feels both proud of and unnerved by the Ramires legacy, the harsh shadow it casts over his cushioned and at times pusillanimous existence. To better earn the family name, he decides to dramatize some of the family heroics in a novel for a friend’s literary magazine, plundering an uncle’s battle-epic-style poem and some Walter Scott novels. Doubling and interlocking with this endeavor is a political end: when the influential position of deputy opens up in local government, Gonçalo makes up his mind to run, even though that entails partnering with Cavaleiro, a despised former friend and onetime suitor to his sister.

Ramires appeared in serial form, in Revista Moderna, starting in November 1897, but was interrupted when the publication went out of business. Eça completed the story but died before revising a final portion of the proofs, not that this is in any way obvious now. (In this case, the job of editing was handed to the writer Júlio Brandão.) As with his rambunctious fable The Relic (1887), the novel is structured around a bold narrative conceit. As the story proceeds, Gonçalo not only manages to convince himself that he is on a path that would impress his storied forebears, but, echoing Don Quixote, more or less dreams his way into their twelfth-century world—the novel includes colorful excerpts of his literary effort, a pastiche of Herculano, it turns out, full of chain-mail and dismounts from horses, and humorous cries of things like “Stand ready, crossbowmen, stand ready!” Ramires was well received, and even satisfied de Assis, who called it “a new blossoming for our Eça.” (Under Salazar, the book was popular with the right for its romantic depiction of the country: such readings must have included some pretty willful downplaying of its lampooning and quietly damning portrayal of nationalist mythologizing and self-justifying codes.)

Spending time with Eça’s novels, a reader becomes familiar with certain recurring themes and patterns. There’s a slightly whimsical predilection for associating certain types of characters with physical traits—good people will probably have beaming white teeth, and villains tend to be blessed with excellent penmanship. A person’s skin might bring to mind a type of stone, and that will be significant. Other examples are more general: Eça tends, for instance, to associate beauty and illness, romantic passion and woe. But if the narration and dialogue sometimes suggest a humane pessimism, sad and indignant over how cruelly humans can treat one another, the clear, spirited pleasure Eça takes in describing all that he enjoys gives his fiction an underlying buoyancy. Consider this, from Ramires:

After briefly smoking a cigar, Videirinha, took up his guitar again. On the far side of the garden, fragments of whitewashed wall, the occasional stretch of empty road, the water in the great fountain, all shone in the moonlight silvering the hills; and the stillness of the trees and of that luminous night seeped into the soul like a soothing caress. Titó and Gonçalo were enjoying the famous moscatel brandy, one of the Tower’s most precious antiquities, and listening, silent and rapt, to Videirinha, who had withdrawn to the shadows at the back of the balcony. Never had he played more tenderly, more sweetly. Even the fields, the vaulted sky and the moon above the hills were listening intently to the mournful fado. Below, in the darkness, they could hear Rosa clearing her throat, the servants’ muffled footsteps, a girl’s occasional suppressed laughter, a hunting dog flapping its ears, and all those sounds were like the presence of people subtly drawn to that lovely song.

Both The Yellow Sofa and The Illustrious House of Ramires were written during the decade in which Eça finished The Maias. Though similar in its style and preoccupations to his other work, The Maias is more elaborate in structure and ambitious in scope; it is a culmination of his vision and best tendencies. The book is full of memorable, patiently unfurling episodes, a flow of set pieces occurring indoors and out that are often quotidian on the surface, and yet so sensuously and precisely registered as to make the reader feel like a visiting, happily observing ghost. The novel’s central figure, Carlos, has two sides: although he’s published a book, aspires to start an intellectual review, and radiates a charisma that works magic on men and women alike, Carlos’s medical practice and state-of-the-art laboratory are little visited. He spends his time instead with friends, who tend to be wealthy, titled, cultivated, and absorbed in the same kind of distractions as he is. (Their lives, too, are a “sarabande of lovers and husbands.”) This pursuit of idle pleasure at the expense of more solid aims, especially for someone of such ancestry and promise, is unintelligible to Carlos’s grandfather and de-facto dad, Afonso, a stolid and mysterious relic of an older Portugal. Carlos’s actual father killed himself after his wife ran off with an Italian, one of a number of tragic episodes alluded to in the family’s history.

Much more can be singled out in The Maias: the complex function of houses and properties in the story, Carlos’s funny, often amiable assortment of friends (they include Ega, an extravagant, monocled stand-in for the author), the lovely woman with whom he has a relationship, and the treachery that puts his life in chaos. As Eça develops this material, the trajectory of the family and that of Portugal become increasingly alike.

For all the splendid dinners, witty rejoinders, lovely views and moods, it is painfully clear that the country is stagnant, caught between daunting, inapplicable old standards on one side and the pressure of keeping up with Paris on the other. (A giveaway of foolishness in the novel is to often say “Chic!”) At the center of The Maias are a political vacuum—pompous and know-nothing officials are one of Eça’s regular satirical targets—and an intoxicating societal inertia. “We may not be cretins, but we have become cretinised,” Ega, Carlos’s (non-producing) writer friend declares. Late in the book, characters talk of present turmoil in France; the mood is apprehensive, with nobody able to say what’s about to happen to their country: “planting vegetables is the only thing one can do in Portugal—until, that is, the revolution comes, and some of those strong, original, energetic elements currently buried down below finally come to the surface.” Receptive to but baffled by his grandson’s generation, Afonso asks: “Then why don’t you two do something to bring about that revolution? Why, for God’s sake, don’t you do something, anything?” - James Guida

http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/05/31/the-proust-of-portugal-eca-de-queiros/

When reading The Illustrious House of Ramires, it is difficult not to imagine the sound of pen scratching at paper. Barely a character appears who is not, in some way, engaged in the act of writing. From Father Soeiro’s history of the cathedral at Oliveira and Tonio’s compendium of scandals committed by Portugal’s oldest families to the novella whose composition sits at the novel’s center, its content largely drawn from an epic Romantic poem by the protagonist’s Uncle Duarte, The Illustrious House is crammed to bursting with aspiring writers. Aggrieved letters are sent to the newspapers, archives sifted through, periodicals founded, the full spectrum of literate and literary nineteenth-century life laid out before the reader.

That this vision of Portugal should be rendered by the act of writing is only appropriate. As a novelist far removed from the country of his birth, acting as Portuguese consul in Havana, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Bristol, Eça de Queirós occupied a space wherein Portugal was not so much a rocky, sloping strip along the Iberian peninsula as it was a whirlwind of inky words and paper documents. Born in 1845 in the northern Portugal town of Povoa de Varzim and educated in law at the prestigious University of Coimbra, he went on to immerse himself in the literary culture of his age, his country, and his continent. From his diplomatic position in the United Kingdom, he composed a series of missives for readers of a Brazilian periodical, in which he abstracted the oddities of British life into delightful anecdotes and observations. These letters, available in English translation courtesy of Alison Aiken and Ann Stevens in Carcanet’s Eça’s English Letters, reveal an author of unstinting curiosity, whose fingers could barely be prized away from his pen. Given that this period also marked the composition of his most famous novels, including his masterpiece, The Maias, published in 1888, we are left with the undeniable image of a man for whom writing was life.

But is life writing? How accurately can words, strung into sentences that themselves are then strung into novels and poems, represent life? As a reader of Balzac and Flaubert, Eça de Queirós was alive to the distance between art and life, words and acts, and it is this space that provides The Illustrious House of Ramires, Eça de Queirós’s final novel which was published posthumously in 1900 and now appears in Margaret Jull Costa’s lively translation, with its dramatic thrust and intellectual fizz. Set in late nineteenth century Portugal, the novel documents Gonçalo Ramires’s attempt to write a historical novella based upon the heroic exploits of his twelfth-century ancestors. As a descendant of a family older than the Kingdom of Portugal itself, Gonçalo bears the weight of a formidable family name. Eager to enhance his reputation in preparation for a planned entry into parliament, he sets out to win the prestige bestowed by the act of literary composition. It is to be an act of aggrandizement.

And yet, as Gonçalo’s novella evolves, it throws into relief both the inadequacies of its writer and the gap that exists between the romanticized past and the real present. Lacking imagination, Gonçalo is best described as a creative plagiarist, taking details from “Sir Walter Scott and various stories published in Panorama” and stitching them onto a poem composed by his Uncle Duarte. In the landscape of The Illustrious House of Ramires, glory is almost always borrowed and the perception of past triumphs looms large. With Gonçalo’s jejune straining for glory, de Queirós presents us with a protagonist and a nation attempting to live up to a supposedly heroic past that we come to suspect actually may never have been such. There is a sense, held by most of the novel’s characters, that Portugal’s greatest achievements lay in the distant past. The very distant past, actually: the exploits of the knight Martim Moniz (who died in 1147), the explorer Vasco de Gama (who died in 1524), and the poet Luís Vaz de Camões (who died in 1580) still cast a long shadow over nineteenth-century Portugal.

The resulting sense of inadequacy is further underlined in Margaret Jull Costa’s essential and informative afterword. We learn that it is during the period of the novel’s composition that, during a conflict with Britain, Portugal received a blow to its confidence. Having lost Brazil earlier in the century, Portugal was now forced to confront the failure of its Mapa Cor-de-Rosa project, an attempt to link the colonies of Mozambique and Angola, so as to create a swathe of Portuguese territory across Africa. Thwarted by the British, insecurity took root and bred bluster. And so this bluster, which was ultimately a desire to restore Portuguese glory, is endlessly parroted by the novel’s milieu.

And in The Illustrious House of Ramires, Portugal, like Gonçalo, is found wanting. The present is not the past and words cannot hide that. In Portugal at the end of the nineteenth century, sieges are conducted not by armies but by gossips. The Lousada sisters, “scrutineers of everyone’s life, the spreaders of all malicious gossip, the weavers of all intrigues,” lay siege to the Casa dos Cunhais, home to Gonçalo’s beloved sister and her husband. In response, our hero and his friends cower and peer “like soldiers at an arrow slit in a castle” through a gap in the curtain. It is from this mischievous puncturing of bravado and bluster that much of the pleasure of reading The Illustrious House of Ramires is gained. And, of all the characters the author skewers with relish, none are run through the wringer quite like Gonçalo.

Gonçalo is a man engaged in the act of writing himself. He uses words to self-dramatize and fabricate, to clothe his flaws. He is, above all, a coward. We read how he barricades himself in his room to avoid the drunken rampages of his gamekeeper Rolho and, after breaking a promise, runs from the wronged farmer, Casco. These act of cowardice are then refashioned in subsequent retellings. The sickle, for example, wielded by Casco, becomes a gun. Gonçalo wishes to be a hero, but character dictates otherwise: “cowed by fear, by the wretched shiver that always ran through him whenever he was confronted by any danger or threat, and which irresistibly forced him to retreat, to withdraw, to run away.”

He is also not a man of his word, his nobility undercut by broken promises and opportunistic maneuvers. To advance his political career, he is willing to switch political allegiance, to seek union with a former enemy and to expose his sister to infamy. And yet, it is this failure to live up to an ideal that makes Gonçalo so compelling. One of the most contradictory and complex characters in fiction, he is also one of the most loveable and democratic, prone to acts of charity. He rejects the title of “Dom” and speaks on terms of equality with his servants. His friends are drawn from less gilded background—Videirinha, for example, singer of the Ramires fado, is the son of a pharmacist.

Indeed, the process of democratization—which was well underway in Portugal at the time of the novel’s writing—is present throughout the novel. Occasionally, it is reacted to. Gonçalo laments that, “despite his native talent and his name, his extraordinary lineage and those ancestors who had built the Kingdom,” he lacks the authority of an elected official. The spell cast by his name is on the wane. The words that invoke the illustrious past of his house no longer have quite the same clout as they once did. That being said, democracy in the Portugal of the novel is severely limited. Gonçalo sits in a safe seat and his election is, in essence, fixed—“and that was the Election over and done with.” Eça de Queirós presents us with a society transitioning toward democracy, but still with some way to go.

This attention to the imperfect development of both individuals and the societies they form is central to de Queirós’s vision. He is both damning and empathetic, open to the possibility of change. His relation to his characters maintains a fascinating balance between acidic contempt and humane affection. These oscillations within his prose are present within his most famous novel, The Maias, another, more sensationalist account of a family in decline, and yet it is within The Illustrious House of Ramires that this contrast in tone becomes more striking. A tauter, funnier, more scathing novel than its predecessor, one is surprised to learn that the novel was published posthumously. It has the feel of a total work, of a vision distilled.

The novel’s structure, its central narrative periodically interrupted by excerpts from Gonçalo’s work in progress, lays bare the contrast between reality and the ideal, in a way that mirrors de Queirós’s shifting register. As Gonçalo discovers, even the novella has its rules. Form is not easy to escape. By presenting to his readers, a writer bumping up against the limitations of his talents and a man bumping up against the limits of his character, Eça de Queirós creates one of the greatest portraits of human fallibility, of the intermingling of good and bad, honesty and falsehood, that makes up the fabric of our humanity.

Above all, it brings us back to the mysterious relationship between literature and life. The act of composition allows Gonçalo to probe his personality, to cast an eye across the contemporary social scene. His novella facilitates a confrontation with the reality of himself and his society. Gonçalo’s shortcomings as a writer do not undermine the importance of the act of writing. As we bid farewell to Gonçalo at the novel’s end—and I do confess to an intense sadness at parting—we become aware that what we have read is not just a portrait of a man and the stories he tells about himself, but a stark rendering of a society and the narratives it recites about itself. With The Illustrious House of Ramires, Eça de Queirós gave Portugal a new voice with which to inscribe itself on the world. - Gary Michael Perry

http://www.musicandliterature.org/reviews/2017/11/6/eca-de-queiross-the-illustrious-house-of-ramires

Margaret Jull Costa’s new translation from the Portuguese of Eça De Queiros’ The Illustrious House of Ramires, first published in 1900, is a delicate and humorous translation which holds the power to make even the cynical twenty-first century reader chuckle. Its anti-hero protagonist, Gonçalo Mendas Ramires, also referred to throughout as “The Nobleman of the Tower,” holds his familial lineage, talents, and self-worth, in the highest regards. His lack of self-awareness and assurance of his own nobility, combined with his natural inability to accomplish almost nothing, provide for a delectable read. Costa’s re-translation highlights her translating powers to both preserve and portray a world that has been left behind by the end of the nineteenth century, whilst highlighting a kind of humor and irony that some might claim to be the definite marker of the cynical twenty-first century.

“Few lineages, even those dating from the same period, could trace their ancestry by the purest of male lines” (4) The Nobleman declares early in the novel. Finding such great pride in his own bloodline, the Nobleman has decided to dedicate his life, i.e. the two hour period between lunch and pre-dinner drinks, to the task of crafting a novella about his own family linage, dating to the time when nobleman defended their castles against menacing “large companies of soldiers” (115), engaged in writing poems to their beloveds, and died glorified death in the name of their family’s honor. Although the Nobleman insists on reminding all who cross his path of his family’s glorious lineage, his nineteenth century life is anything but heroic. Instead, he spends his time roaming the gardens, attending luncheons and galas, and contributing the local gossip. Not to mention, writing his novella, (“Ah, but the sheer effort of writing that dense, difficult chapter” (51)) when the illusive inspiration compels him to do so. “As he walked along that silent, still damp path, Goncalo was thinking of his ancestors. They were reemerging in his novella as such solid, resonate figures! And his confident understanding of those Afonsine souls was proof his own soul was made of the same mettle, and had been carved from the same fine block of gold” (119).

The stark difference between The Nobleman of the Tower’s inner monologue and the life the readers get to witness and relish in, courtesy of the narrator, is what kept me turning the pages. The disconnect between these two voices equates to constant winks exchanged between the narrator and the readers. “Work as a lawyer in Oliveira or eve in Lisbon itself? No, he couldn’t, not with his innate, almost psychological horror of legal proceedings and paperwork” (25). Costa’s translation is a fresh reading of a novel written for a time and century long forgotten. Her translation built an approachable bridge for the modern reader.

I couldn’t help but liken the reading of Costa’s retranslation of The Illustrious House of Ramires to a book form of reality TV. That is, a highly sophisticated and worthwhile reading experience in which readers gleefully snicker at the main character’s overly inflated sense of self-worth and tantrums brought on by his natural born entitlements, Big Brother style. “Not a single tenant or laborer had answered his despairing cries! Out of his five servants, none had rushed to his aid” (123). As if The Nobleman was a contender in one of those shows where the characters are so overly concerned of their own position of the social totem-poll, that the viewers/reader leave gaining an enormous sense of relief, feeling better about their own uneventful life just for witnessing such egocentric characters. It’s other similarity to the reality TV show genre is that the camera in the Nobleman’s life is always running. Thus, viewers possess the power to tune in for the sensational primetime edited scenes, or waste their time at their corporate nooks and desks, watching the uneventful livestream. Like any good reality TV show, it’s the Nobleman’s self-assurance, self-importance, and general feelings of entitlement the drive the reader to turn the pages. And like any other good reality TV series, the pleasure for the readers of Des Queirós’ novel immerges from combining the protagonist’s pretentiousness, highlighted by his lack of actual talent, and the narrator’s brilliant work of juxtaposition between the two.

Perhaps equating a late nineteenth century book to such an infamous genre of mindless TV watching is a bit misleading, for reading The Illustrious House of Ramires is neither infamous nor mindless. Yet the novel is slow moving. If you are a reader that enjoys lengthy ruminations and extravagant sword fights of courageous ancestors who recite poetry before they draw their swords, if you cherish a world that relied less on quick come-backs and the constant need for instant gratification, this is the book for you.

When first published, Des Queirós received praise for the construction of this novel: for the readers are firsthand witnesses to The Nobleman’s novella writing; they join him at his desk as his forefathers come to life. For this, Des Queirós still deserves full glory. For it is in those moments where The Nobleman sits at his desk, that his characters take hold. These are some of the most action filled moments of the novel.

“’Forward men!’”

“’To the death!’”

“’Hold hard for Baiáo!’”

“’Victory for the Ramires!’” (117).

The Nobleman’s one talent comes to life at these sittings. The olden worlds he creates on the page portray his true flair and stronghold. It is only fitting, that the worlds The Nobleman conjures in his imagination are the most entertaining. Nonetheless, most of the novel is dedicated to portraying the somewhat dull, yet pompous life The Nobleman leads. Readers learn about The Nobleman’s rich, and at times, tedious lineage, his cordial and unaffectionate relationship to his only sister, his mundane routines of attending galas, luncheons, and contributing to local gossip, and his disdain of most humans, particularly women.

It is the humor that carries the weight of this novel. And it’s to Costa’s translation handiwork that readers owe their thanks to. For translated humor is hardly an easy feat. Yet Costa makes it look effortless and natural, just like any good translator should. - Mor Sheinbein

José Maria de Eça de Queirós, where have you been all my life? Dead, obviously—the man died in 1900 at the age of fifty-five—but his novels are acknowledged as classics in his native Portugal, and by well-educated people the world over. As readers of the Daily may remember, I tore through my first Eça book a few months ago. And now Margaret Jull Costa has translated The Illustrious House of Ramires, his last novel, about a provincial aristocrat—a dreamer and amateur historian—who tries to write a novella based on the exploits of his Crusader ancestors. Comedy and mayhem ensue. As in The Crime of Father Amaro, Eça’s tone shifts from light to dark, from tender irony to horror, then back again, in a single page, almost in a sentence, as Ramires—like a fin de siècle, Portuguese Quixote—tries to re-create the chivalry of his forbears. The plot is full of surprises, but even when our hero is just sitting at his desk, dreaming up deeds of valor, Eça takes us inside the fantasy, until we start to wonder whether Ramires has crossed the fine line between idiocy and genius. It’s rare to find such a thrilling portrait of the writer at work. —Lorin Stein

José Maria Eça de Queirós, The Maias: Episodes from Romantic Life, Trans. by Margaret Jull Costa, New Directions; Reprint ed., 2007.

Set in Lisbon at the close of the nineteenth century, The Maias is both a coming-of-age novel and a passionate romance.

Our hero Carlos Maia, heir to one of the greatest fortunes in Portugal, is rich, handsome, generous and intelligent: he means to do something for his country, something useful, something that will make his beloved grandfather proud. However, Carlos is also a bit of a dilettante. He drifts along, becoming a doctor and pottering about in his laboratory, but spends more and more time riding his splendid horses or visiting the theater, having affairs or reading novels. His best friend and chief partner in crime, Ega, is likewise engaged in a long summertime of witticisms and pleasure. Carlos however is set on a dead reckoning course with fate―with the love of his life and with a terrible, terrible secret...

A veteran translator of Saramago and Pessoa, Jull Costa delivers Quierós's 1888 masterpiece in a beautiful English version that will become the standard. Rich scion Carlos de Maia—like his best friend, writer João da Ega—is an incorrigible dabbler caught in the enervated Lisbon of the 1870s. His parentage is checkered: Carlos's mother runs off with an Italian, taking his sister, Maria, but leaving Carlos with his father, Pedro, who soon shoots himself. Raised by Pedro's father, Afonso, the adult Carlos returns with a medical degree to live with Afonso in the family's cursed Lisbon compound. His very romantic, very doomed affair with Madame Maria Eduarda Gomes sets in motion a train of coincidences, deftly prefigured, that resonantly entwines Carlos's fate with that of his father and spreads all of Portuguese society before the reader. Quierós has a magisterial sense of social stratification, family and the way eros can make an opera of private life. The novel crystallizes the larger unreality of an incestuous society, one that drifts, even the elite heatedly acknowledge, into decline. The neglect of the big Iberian 19th-century novelists—Galdós, Clarín and Quierós—remains a puzzle. This novel stands with the great achievements of fiction. - Publishers Weekly

Baudelaire pretended to be surprised that anyone could think of Balzac as a realist. It had always seemed to him, he said, that the novelist was ‘a passionate visionary’. The only perverse element in this claim is the suggestion that Balzac was not a realist as well as a visionary, and more broadly, that realism is not a vision. At one of the founding moments of European realism, in the early pages of Le Père Goriot, Balzac describes, or rather keeps saying he can’t describe, the miserable Paris boarding-house where much of the novel is set:

The first room exhales an odour for which there is no name in the language, and which should be called the ‘odeur de pension’. The damp atmosphere sends a chill through you as you breathe it; it has a stuffy, musty and rancid quality; it permeates your clothing … Yet, in spite of these stale horrors, the sitting-room is as charming and as delicately perfumed as a boudoir, when compared with the adjoining dining-room.

The panelled walls of that apartment were once painted some colour, now a matter of conjecture, for the surface is encrusted with accumulated layers of grimy deposit, which cover it with fantastic outlines.

Then the owner of the house, Mme Vauquer, appears.

She is an oldish woman, with a bloated countenance, and a nose like a parrot’s beak set in the middle of it; her fat little hands (she is as sleek as a church rat) and her shapeless, slouching figure are in keeping with the room that reeks of misfortune, where hope is reduced to speculate for the meanest stakes. Mme Vauquer alone can breathe that tainted air without being disheartened by it … Her whole person explains the boarding-house, just as the boarding-house implies her person [toute sa personne explique la pension, comme la pension implique sa personne].

Writing like this is not a refusal of symbolism, it is a form of it, a selection of details to show what lies beyond the details. Realism in this sense is devoted to a profusion of material signs but also, and more emphatically, to a theory of the readability of those signs. The odour that can’t be named is metonymically named at once; the original colour of the walls doesn’t matter, since the encrustations and fantastic outlines carry the full message of misfortune. In the great works of realism surfaces always speak, they communicate with the depths the way a trap-door communicates with a cellar or a space beneath a stage. And the attraction of the Balzac instance lies in the literary doctrines it skirts but doesn’t endorse. It does not say that Mme Vauquer is the product of her environment, although she might well be; it does not say her house is the result of her personality, although that might be true too. It asserts a correspondence between place and person and invites us to think of one in terms of the other. But there is none of the narrow determinism that is so often associated with realism and even more with naturalism; no actual suggestion of causality at all, since explanation and implication are rather different processes and in this context half-metaphorical anyway. The damp room and the sharp nose have equal rights, and both are very talkative.

I thought of this theory of readable surfaces because I was trying to understand my pleasure in the beautifully crafted descriptions in Eça de Queirós’s masterly novel The Maias, extremely well rendered in Margaret Jull Costa’s new translation. The novel is set in Lisbon in the 1870s: 1875 to 1878, to be precise, with a couple of flashbacks to establish the family history, and an epilogue placed in 1887, the year before the book was first published. It begins and ends with a house, as in Balzac, and the city – or more precisely, a certain style of life in that city – is in one sense its chief character. But the descriptions do more than create atmosphere or even give us this character. They hover on the edge of explanation, they promise to interpret a whole world for us; but tactfully never quite do this, thereby avoiding the determinism that I have just evoked and that critics regularly associate with Eça de Queirós. Everything is rich and charming here, even the weather and the light, as if the writer had managed to locate in reality the paradise of Baudelaire’s ‘Invitation au Voyage’, that place of ‘order and beauty/luxury, calm and pleasure’. Well, the same place tinged with a melancholy that arises from its very attractions, marked in the following quotations by the excess of velvet, the mildly threatening, over-modern steel, and the giveaway word ‘torpor’:

I thought of this theory of readable surfaces because I was trying to understand my pleasure in the beautifully crafted descriptions in Eça de Queirós’s masterly novel The Maias, extremely well rendered in Margaret Jull Costa’s new translation. The novel is set in Lisbon in the 1870s: 1875 to 1878, to be precise, with a couple of flashbacks to establish the family history, and an epilogue placed in 1887, the year before the book was first published. It begins and ends with a house, as in Balzac, and the city – or more precisely, a certain style of life in that city – is in one sense its chief character. But the descriptions do more than create atmosphere or even give us this character. They hover on the edge of explanation, they promise to interpret a whole world for us; but tactfully never quite do this, thereby avoiding the determinism that I have just evoked and that critics regularly associate with Eça de Queirós. Everything is rich and charming here, even the weather and the light, as if the writer had managed to locate in reality the paradise of Baudelaire’s ‘Invitation au Voyage’, that place of ‘order and beauty/luxury, calm and pleasure’. Well, the same place tinged with a melancholy that arises from its very attractions, marked in the following quotations by the excess of velvet, the mildly threatening, over-modern steel, and the giveaway word ‘torpor’:

in the background, the broad blue Tejo river, as blue as the sky, gave off a glitter of finely powdered light

in the silence, the lovely afternoon seemed to spread out around them, softer and calmer. In the dustless air, without the shimmer created by the sun’s strongest rays, everything took on a delicate clarity

the curtain was slightly drawn back, and through the gap, he had a glimpse of one warm cosy corner of the room, its damask furnishings bathed in a tender rose-pink light: the cards lay waiting on the whist table; on the sofa embroidered in subtle silks, a languid, thoughtful Dom Diogo was gazing into the fire and stroking his moustaches

the afternoon was drawing to a close, in an Elysian peace, without a breath of wind, and with small, high, pink-tinged clouds motionless in the broad sky; the fields and distant hills on the other shore were already disappearing beneath a velvety, violet mist; the water lay smooth and polished as a perfect sheet of new steel

a soft light, slipping sweetly down from the dark blue sky, gilded the peeling façades, the bare tops of the municipal trees, and the people sitting idly about on benches; and the slow whisper of urban indolence, along with the soft air of a benevolent climate, seemed to seep gradually into that stuffy office, to slither over the heavy velvets, the varnished furniture, and to wrap Carlos in a quiescent torpor.

This place looks and feels wonderful, it seems to be where we’d like to live (where I’d like to live) and where Eça de Queirós himself, no doubt, wouldn’t have minded living – he wrote the novel while he was Portuguese consul in Bristol. Before that he had been consul in Havana and Newcastle. All five of the novels published in his life time – Cousin Bazílio, 1878, The Crime of Father Amaro, 1875, The Mandarin, 1880, The Relic, 1887, The Maias, 1888 – appeared while he was working in England. He was born in 1845 and died in 1900.

But this place also, we know as we think about the soft light and the silk-covered sofa, is likely to suffocate us, and perhaps Eça de Queirós could not have written his novels there. He suggests this discreetly by having a talented and witty man in the book fail to write anything at all in spite of his many projects, and by having his hero, the above-named Carlos, become a doctor who scarcely practises and a scientific experimenter who doesn’t experiment. But is the place to blame? Or is it an elegant and agreeable excuse for failure? Does it merely offer a temptation to fail? What is the relation between culture and climate, and between climate and human achievement? Is there a relation? These are the questions the descriptions implicitly ask and leave floating. Lisbon and Portugal imply or at least mirror the lives of (some of) their rich and self-indulgent citizens. Or is it the other way round? Either way a claim to explanation seems to be going too far, as it no doubt already was in Balzac.

Balzac is named several times in The Maias. Two characters are said to have a ‘Balzacian eye’, and Balzac is elsewhere called a ‘prodigy of observational powers’. A love nest is called the Villa Balzac, an intricate, critical irony because the owner of the house is a ‘great fantasist’ far from fully aware of what he is doing when he adopts the great realist as his ‘patron saint’. The book itself, I should say, is subtitled ‘Episodes from Romantic Life’, so these touches are important. ‘Romantic’ in this context has all kinds of associations, and its near-synonyms could include ‘poetic’, ‘stylish’, ‘idealistic’, ‘liberal’, ‘deluded’. As in ‘all English songs were alike, they always struck the same sorrowful romantic tone,’ or (spoken of a poem that has just been recited) ‘such romantic outpourings’. ‘Literature,’ we are told, ‘used to be all about the imagination, fantasy, ideas. Nowadays, it’s all about reality, experience, facts, documentation.’ And about money, which is this character’s main translation of ‘facts’. But then he calls it ‘marvellous money’, slipping unconsciously back into the romantic mode, in spite of his attempt at irony. Eça de Queirós’s chief question, perhaps, is whether realism is possible in Portugal, in literature or anything else, and his mischievous suggestion is that ‘Portugal’ may just mean ‘romantic’ – there couldn’t be episodes of any other sort of life there. He is doing this, however, with sly intelligence, in an undeniably realist Portuguese novel.She is an oldish woman, with a bloated countenance, and a nose like a parrot’s beak set in the middle of it; her fat little hands (she is as sleek as a church rat) and her shapeless, slouching figure are in keeping with the room that reeks of misfortune, where hope is reduced to speculate for the meanest stakes. Mme Vauquer alone can breathe that tainted air without being disheartened by it … Her whole person explains the boarding-house, just as the boarding-house implies her person [toute sa personne explique la pension, comme la pension implique sa personne].

Writing like this is not a refusal of symbolism, it is a form of it, a selection of details to show what lies beyond the details. Realism in this sense is devoted to a profusion of material signs but also, and more emphatically, to a theory of the readability of those signs. The odour that can’t be named is metonymically named at once; the original colour of the walls doesn’t matter, since the encrustations and fantastic outlines carry the full message of misfortune. In the great works of realism surfaces always speak, they communicate with the depths the way a trap-door communicates with a cellar or a space beneath a stage. And the attraction of the Balzac instance lies in the literary doctrines it skirts but doesn’t endorse. It does not say that Mme Vauquer is the product of her environment, although she might well be; it does not say her house is the result of her personality, although that might be true too. It asserts a correspondence between place and person and invites us to think of one in terms of the other. But there is none of the narrow determinism that is so often associated with realism and even more with naturalism; no actual suggestion of causality at all, since explanation and implication are rather different processes and in this context half-metaphorical anyway. The damp room and the sharp nose have equal rights, and both are very talkative.

in the background, the broad blue Tejo river, as blue as the sky, gave off a glitter of finely powdered light

in the silence, the lovely afternoon seemed to spread out around them, softer and calmer. In the dustless air, without the shimmer created by the sun’s strongest rays, everything took on a delicate clarity

the curtain was slightly drawn back, and through the gap, he had a glimpse of one warm cosy corner of the room, its damask furnishings bathed in a tender rose-pink light: the cards lay waiting on the whist table; on the sofa embroidered in subtle silks, a languid, thoughtful Dom Diogo was gazing into the fire and stroking his moustaches

the afternoon was drawing to a close, in an Elysian peace, without a breath of wind, and with small, high, pink-tinged clouds motionless in the broad sky; the fields and distant hills on the other shore were already disappearing beneath a velvety, violet mist; the water lay smooth and polished as a perfect sheet of new steel

a soft light, slipping sweetly down from the dark blue sky, gilded the peeling façades, the bare tops of the municipal trees, and the people sitting idly about on benches; and the slow whisper of urban indolence, along with the soft air of a benevolent climate, seemed to seep gradually into that stuffy office, to slither over the heavy velvets, the varnished furniture, and to wrap Carlos in a quiescent torpor.

This place looks and feels wonderful, it seems to be where we’d like to live (where I’d like to live) and where Eça de Queirós himself, no doubt, wouldn’t have minded living – he wrote the novel while he was Portuguese consul in Bristol. Before that he had been consul in Havana and Newcastle. All five of the novels published in his life time – Cousin Bazílio, 1878, The Crime of Father Amaro, 1875, The Mandarin, 1880, The Relic, 1887, The Maias, 1888 – appeared while he was working in England. He was born in 1845 and died in 1900.

But this place also, we know as we think about the soft light and the silk-covered sofa, is likely to suffocate us, and perhaps Eça de Queirós could not have written his novels there. He suggests this discreetly by having a talented and witty man in the book fail to write anything at all in spite of his many projects, and by having his hero, the above-named Carlos, become a doctor who scarcely practises and a scientific experimenter who doesn’t experiment. But is the place to blame? Or is it an elegant and agreeable excuse for failure? Does it merely offer a temptation to fail? What is the relation between culture and climate, and between climate and human achievement? Is there a relation? These are the questions the descriptions implicitly ask and leave floating. Lisbon and Portugal imply or at least mirror the lives of (some of) their rich and self-indulgent citizens. Or is it the other way round? Either way a claim to explanation seems to be going too far, as it no doubt already was in Balzac.

The writer’s master and companion in this venture, in spite of the frequent mentions of Balzac, is Flaubert, and especially the Flaubert of Sentimental Education. Carlos, when a student, tries his hand at a few ‘historical tales’ in the manner of Salammbô, and at one point Eça de Queirós borrows from Madame Bovary the idea of a travelling coach as a place for a lovers’ rendezvous. But then he quotes literally from Sentimental Education – ‘it was like an apparition,’ both writers say when the love of our hero’s life presents herself – and his book ends with a brilliant, affectionate parody of Flaubert’s bitter last joke. In Sentimental Education two old friends, having failed in everything, recall an episode from their schooldays: a visit to a brothel. Was that a success at least? It could have been, but one of the boys panicked in his embarrassment, and ran off to escape the laughter of the young women. Since he was the one who had the money, the other boy had to leave too. Now they tell each other the story once again, in great detail, ‘each one completing the memories of the other’. One of them says: ‘That’s the best thing we ever had’ – ‘C’est là ce que nous avons eu de meilleur.’ The other says perhaps it was. ‘That’s the best thing we ever had.’ The double irony is devastating, a perfect instance of what Flaubert in a letter called ‘the comedy that doesn’t make us laugh’. The men are probably right, this was the best thing they ever had. And what they had was nothing.

At the end of The Maias, two old friends, agreeing that they have ‘failed in life’, become philosophical about this outcome. The moral is not that they could have done better, but that they shouldn’t have been trying – which is just as well, because they certainly weren’t. ‘The futility of all effort’ is what it all comes down to. ‘There was no point in trying to achieve anything on this Earth, because … everything ends in disillusion and dust.’ In fact, this character continues his argument, ‘If someone were to tell me that down there the fortune of a Rothschild or the imperial crown of Carlos V were just waiting for me, and that it could be mine if I ran to grab it, I wouldn’t so much as quicken my step.’ His companion agrees ‘with great conviction’.

And they slowed their step as they went down the Rampa de Santos, as if that really were the road of life, along which one should always walk slowly and scornfully, certain, as they were, of finding at the end only disillusion and dust.

But then they remember they are late for drinks before dinner with friends. There is no cab in sight, but they could possibly catch the tram that has stopped some little distance away from them, its red lantern stationary in the dark. If they run for it, that is. They are ‘filled by hope and by a need to make one last effort’, and the novel ends in this way:

‘We might still catch it!’

‘We might still catch it!’

Again the lantern slid away and fled. In order to catch the tram, the two friends started racing desperately down Rampa de Santos and along the Aterro beneath the initial glow of the rising moon.

The glance at Flaubert is clearly an act of homage and Eça de Queirós wants us to know that someone else has told this sad story before and told it incomparably. But because that earlier telling is incomparable, Eça de Queirós is not trying to repeat it. He is translating it to another country and shifting its mood. The failure is roughly the same in both cases. A whole privileged generation, represented by these two men and others, has missed its chance, whether in the 1840s or the 1870s; and the final conversation suggests in each case that the protagonists are a long way from understanding what has happened to them. But the thought of the two men literally running when they have just sworn never to quicken their metaphorical step is funny in a way in which Flaubert’s grim irony is not, and this perception has a lot to do with the whole tone of the book, briefly illustrated in the descriptions I quoted above. At the heart of Flaubert’s world is a void, a profound belief in the disillusion and dust that are just fancy words for the Portuguese characters. If the French boys had had a wonderful night at the brothel it would still have rotted in the memory, and left them with a later desolation, only in a different register. In Eça de Queirós’s world characters sacrifice their ideals and their energies to sheer self-pampering; they just cannot say no to a pleasure if it comes their way. In one sense this story is even sadder than Flaubert’s, precisely because it’s kinder and further removed from anything like purifying or levelling anger. But at least someone, somewhere, is having a good time.

There are only two Maias left, Afonso and Carlos, grandfather and grandson. The missing generation is represented by Pedro, who married against Afonso’s wishes and was then abandoned by his wife, who ran off with an Italian. Pedro, already depressive in temperament, couldn’t bear the disgrace and shot himself in his room at Ramalhete. There were two children, Carlos and a sister whom the mother took away with her and who is said to have died in childhood. In fact, this was one of her mother’s fictions, and the sister’s reappearance in Lisbon as a stranger, apparently married to a Brazilian, not knowing herself to be a member of the Maia family – she is pretty much the last person to find out – moves much of the plot of the second half of the novel. The plot is not the novel’s main interest, but its switches are strong and interesting enough to be left for the reader to discover, and it will be enough to say that it is Afonso’s death, from a combination of ripe old age and sudden shock, that gives Ramalhete the feel of a ruin, and that Carlos, having lived the good and easy life of a playboy in Lisbon, takes off for long Flaubertian travels in America and Japan, and ends up living in Paris.

Afonso thinks, not long before he dies, that he is beset by an ‘implacable fate’ that robs him first of his son and then of his grandson but that ‘fate’ is really a combination of chance and luxury. ‘Fate’ is what will happen one way or another among the sheer opulence of a world that refuses itself nothing, whether mistresses, lovers, whist, wine or horses. There has to be a good likelihood of damage where the only real loyalty is to what one wants at the moment. But this is rather a moralising way of putting it, and Eça de Queirós is more delicate. At one point, Carlos, in the midst of a great love affair, is asked what he is going to do when his grandfather finds out about this relation with a woman in so many ways apparently unsuitable: a repetition, as far as Afonso is concerned, of Pedro’s behaviour, and therefore in this sense a form of fate, if only as a bad family habit. Carlos, a decent, endlessly likeable fellow, constricted only by the selfishness of extreme privilege, shrugs. ‘For me to be profoundly happy,’ he says, ‘my grandfather will have to suffer a little, just as I would have to be wretched for the rest of my life if I wanted to spare him this unhappiness. That’s how the world is.’ That’s how the world is, and that’s how, in the end, a likeable fellow can kill his beloved grandfather. Even so, Eça de Queirós is not suggesting Carlos is completely wrong. His error, if there is one, is not in choosing his happiness but in under-representing its cost – as if nothing, to a really rich man, could be too expensive. He doesn’t know what it means to pay for things. His good fortune is his misfortune, and his blame, while real enough, can’t really be measured, only evoked.

The same is true of his country at large, or at least of its moneyed class. They want to play at being French or English, but they want to play the game at home. Portugal in 1875 is pictured as the headquarters of cultural underdevelopment, and people there speak of the situation in much the way Latin American intellectuals now ironically speak of theirs: with a sophistication totally lacking in so-called developed countries, they magisterially go on about the lacks and failures of their own. This is one of the reasons, I think, that The Maias reads not only like a long, subtle riff on Sentimental Education but like a discreet forerunner of One Hundred Years of Solitude – the verve of the indictment unravels the very case being made. ‘Here we import everything,’ a character says. ‘Ideas, laws, philosophies, theories, plots, aesthetic, sciences, style, industries, fashions, manners, jokes, everything arrives in crates by steamship.’ A politician explains that Portugal’s problem is the absence of ‘personnel’: ‘Say you need a bishop. There are none. Or an economist. There are no economists either … Even in the lesser professions. Say you want a good upholsterer, for example. There are none to be found.’

The man speaking in the first case is a wit, and in the second an idiot, but the mentality is the same. Everyone in Portugal has an Achilles’ heel of some sort, another character says. ‘Portugal’s other name should be Achilles & Co.’ Portugal’s originality lies in its total lack of originality. The place can’t be blamed for not having what it couldn’t possibly have. Or can it? Portugal in this novel is like a rich man who is just too stylish to do great things – or to do anything much – just as the characters in García Márquez are too deeply in love with their own elegant and witty solitude to think of wanting to end it.

There is an earlier (1965) English translation of The Maias, by Patricia McGowan Pinheiro and Ann Stevens. It reads well, and it understands, as the new translation does not, that an abbé is not the same thing as an abbot. But its language is a little old-fashioned even for its time, and Margaret Jull Costa catches better the fluent intelligence of the Portuguese, especially the lyrical phrase-endings that often lead the way out of irony or melodrama, like slow fade-outs in the movies. An example would be the last sentence of the novel, where the two men race for the tram under what is literally ‘the first clarity of the moon that was rising’. Pinheiro and Stevens have ‘under the light of the rising moon’; Jull Costa has ‘beneath the initial glow of the rising moon’. The second seems a little wordy, the first a little too efficient. But the wordiness may be what is needed, since presumably Eça de Queirós wanted some sort of mildly over-ripe effect for his last unromantic episode from romantic life.

A longer example may help to show the differences – and also perhaps show that they are not large enough to quarrel over. This is, in any event, a fine instance of Eça de Queirós’s style, and a good indication of how a realist can become a (comic) visionary. The scene is the house of an aunt of one of Carlos’s mistresses, an Englishwoman, a place they have borrowed for their secret nights of love. (The first passage comes from the Pinheiro/Stevens translation, the second from Jull Costa.)

Carlos entered and tripped immediately over a mountain of bibles. The whole room was packed with them: they lay in piles on top of the furniture; they overflowed from old hat-boxes; they were mixed up with pairs of galoshes; they had wandered into the hip-bath. All of them were in the same format, wrapped in black binding like battle-armour, sullen and aggressive. The walls were resplendent, decked with cards printed in coloured lettering that irradiated harsh verses from Scripture, stern moral counsels, cries from the psalms, insolent threats of hell-fire. And in the midst of all that Anglican piety, on the night-table beside a small, hard, virginal iron bed, stood two bottles of cognac and gin that were almost empty. Carlos had drunk the saintly old maid’s gin; and her hard bed had become as disorderly as a battlefield.

When Carlos first went in, he had stumbled over a pile of Bibles. Indeed, the bedroom was a veritable nest of Bibles; there were small towers of them on various bits of furniture, others spilled out from old hat-boxes or were jumbled up with pairs of galoshes or had fallen into the hip bath, and all were of exactly the same format, bound in the same scowling, aggressive black leather as if buckled into armour for battle! The walls glowed, lined with cards printed in coloured lettering, radiating austere verses from the Bible, stern moral advice, cries from the psalms, and bold threats of hell-fire. And in the middle of all this Anglican religiosity, at the head of a small iron bedstead, stiff and virginal, stood two almost empty bottles of brandy and gin. Carlos finished off the lady’s gin, and her hard bed was left as turbulent and disorderly as a battlefield.

Each is more literal than the other at times. Pinheiro and Stevens keep the mountain (‘montão’) of bibles, and lose the nest (‘ninho’) of the same; generally stick with a word order that is a little awkward in English (‘wrapped in black binding like battle-armour, sullen and aggressive’, ‘entaladas numa encadernação negra como numa armadura de combate, carrancudas e agressivas’); and hang onto words like ‘resplendent’ and ‘irradiated’ that aren’t entirely convincing in their new home. But then they decide ‘piety’ is better than ‘religiosity’ as a translation of ‘religiosidade’. Jull Costa changes the tenses of the first sentence (literally ‘Carlos entered, stumbling immediately against a mountain of Bibles’, ‘Carlos entrou, tropeçando logo num montão de Bíblias’); adds words (‘indeed’, ‘veritable’), turns piles into towers, but then allows the Bibles simply to ‘fall’ into the hip-bath as they do in the Portuguese. The test perhaps is how we feel about two key moments at the end of the paragraph, the mention of the lady’s gin (‘o gin de santa’, literally ‘the saint’s gin’ or just ‘the gin of the pious lady’) and the verb indicating what the activities of Carlos and his mistress have done to the bed (‘ficou revolto’, literally, ‘remained turned over’). What to keep and what to let go? My sense here is that ‘saintly old maid’ is a little too much, broadens the irony an inch too far; and that ‘turbulent and disorderly’ does just the work it needs to. - Michael Wood

https://www.lrb.co.uk/v30/n01/michael-wood/marvellous-money

José Saramago, Portugal’s only Nobel literature laureate to date, describes “The Maias” as “the greatest book by Portugal’s greatest novelist.” Even so, its 19th-century author, José Maria Eça de Queirós, could use a bit more of an introduction. He may be Portugal’s Flaubert, but like the greatest novelists of many peripheral countries, he remains largely unknown to English-language readers. A new translation of “The Maias” offers an appealing chance to discover him.

Born in 1845, Eça de Queirós (pronounced EH-sah de kay-ROSH) was the illegitimate son of a magistrate, whose support enabled him to study at Coimbra’s elite university. Moving to Lisbon in 1866, he joined a group of writers committed to seeking social reform through literature. Then, from 1872, he lived abroad, serving successively as Portuguese consul in Havana, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Bristol and, finally, Paris, where he died in 1900.

Portuguese society was the target of his 12 novels, only five of which were published in his lifetime, yet Eça de Queirós was very much a cosmopolitan writer. Influenced by both Naturalism and Romanticism, he fearlessly dissected the social decadence of his day. The tools he used were a rich style, passion-driven storytelling and satire. As he saw it, late-19th-century Portugal was a backwater — and he implicitly blamed this on the monarchy, the Roman Catholic Church and the aristocracy.

“Here we import everything,” João de Ega, one of the principal characters in “The Maias,” caustically proclaims. “Ideas, laws, philosophies, theories, plots, aesthetics, sciences, style, industries, fashions, manners, jokes, everything arrives in crates by steamship.”

“The Maias” must have seemed shockingly contemporary in its verismo: its narrative ends in 1887, just a year before the book was published. But it is not a revolutionary tract. Rather, in Margaret Jull Costa’s excellent translation, its appeal remains its strongly etched characters, not only the beloved and enlightened patriarch, Afonso da Maia, and his no-less-wealthy grandson, Carlos, but also assorted snobby aristocrats, drunken writers, greedy politicians, self-important businessmen, social climbers — and beautiful women.

Their principal stage is Lisbon, where at clubs, restaurants, parties, private dinners, even on the street, they argue about politics and literature, gossip poisonously and plan seductions. Indeed, the men devote enormous energy to bedding their associates’ wives. In Ega’s case, alas, the lovely Raquel Cohen’s husband finds out. Carlos, in contrast, soon tires of the Countess de Gouvarinho and “her tenacity, her ardor, her weight.”

The novel’s main plot gets going after Carlos falls for Maria Eduarda, the wife of a wealthy Brazilian, Castro Gomes, who is spending time in Lisbon. When Castro Gomes returns to Rio de Janeiro on business, Carlos makes his move, and Maria Eduarda, “divine in her nakedness,” responds with Flaubertian passion. “Her urgent kisses seemed to go beyond his flesh, to pierce him through, as if wanting to absorb both will and soul,” Eça de Queirós writes approvingly.

A frustrated suitor of Maria Eduarda strikes back, informing Castro Gomes in an anonymous letter of his wife’s betrayal. But when Castro Gomes returns to Lisbon, he has a surprise: he informs Carlos that Maria Eduarda is not his wife but his mistress, a woman with a steamy past whom he is quite glad to be rid of. Stunned, Carlos is also ready to dump her, but she wins him back, recounting the hardship of her life and persuading him of her undying love.

“Suddenly, all he saw, blotting out her every weakness, were her beauty, her pain, her sublimely loving soul. A generous delirium, a grandiose kindness mingled with his love. And bending down, his arms open to her, he said softly: ‘Maria, will you marry me?’ ”

Ah, those 19th-century Romantics.

Well, twists and turns lie ahead, but there is still ample time to dwell on the terminal ennui of these aristocratic Lisboners who seem to have no need to work. And it is their slow-moving world of vapid conversation and fear of change that Eça de Queirós most delightfully mocks. To Alencar’s revolutionary poetry, the Count de Gouvarinho can only tut-tut: “To speak of barricades and make extravagant promises to the working class at a society event, under the protection of the queen, and in the presence of a minister of the crown, is perfectly indecent!”

Gradually, then, while charting Carlos’s travails of the heart, Eça de Queirós paints a picture of a society trapped in a time warp, stubbornly refusing to follow the rest of Europe. And here, far more than Carlos, a sympathetic but spoiled rich boy, it is the unsuccessful writer Ega who seems to speak for the novelist. Ega loves Portugal, but is also unforgiving. “There’s nothing genuine in this wretched country now, not even the bread that we eat,” he laments in a form of conclusion.

Looking again at that remark, it is a bit surprising that Portugal still so loves Eça de Queirós. On the other hand, Portugal has changed: today, it really does belong to Europe. - Alan Riding

I.

The Maias is regarded as the most important work of the late 19th-century Portuguese writer Jose Maria Eça de Queirós. For the most part, the book follows the life of Carlos de Maia and his grandfather, Afonso de Maia, the last remaining male survivors of an extremely wealthy Lisbon family.Young Carlos is raised by his grandfather following the suicide of his father, who killed himself after being abandoned by his wife. Raised unaware of this tragedy, Carlos becomes a doctor and opens a medical practice and laboratory in Lisbon, where he plans to make significant medical discoveries.