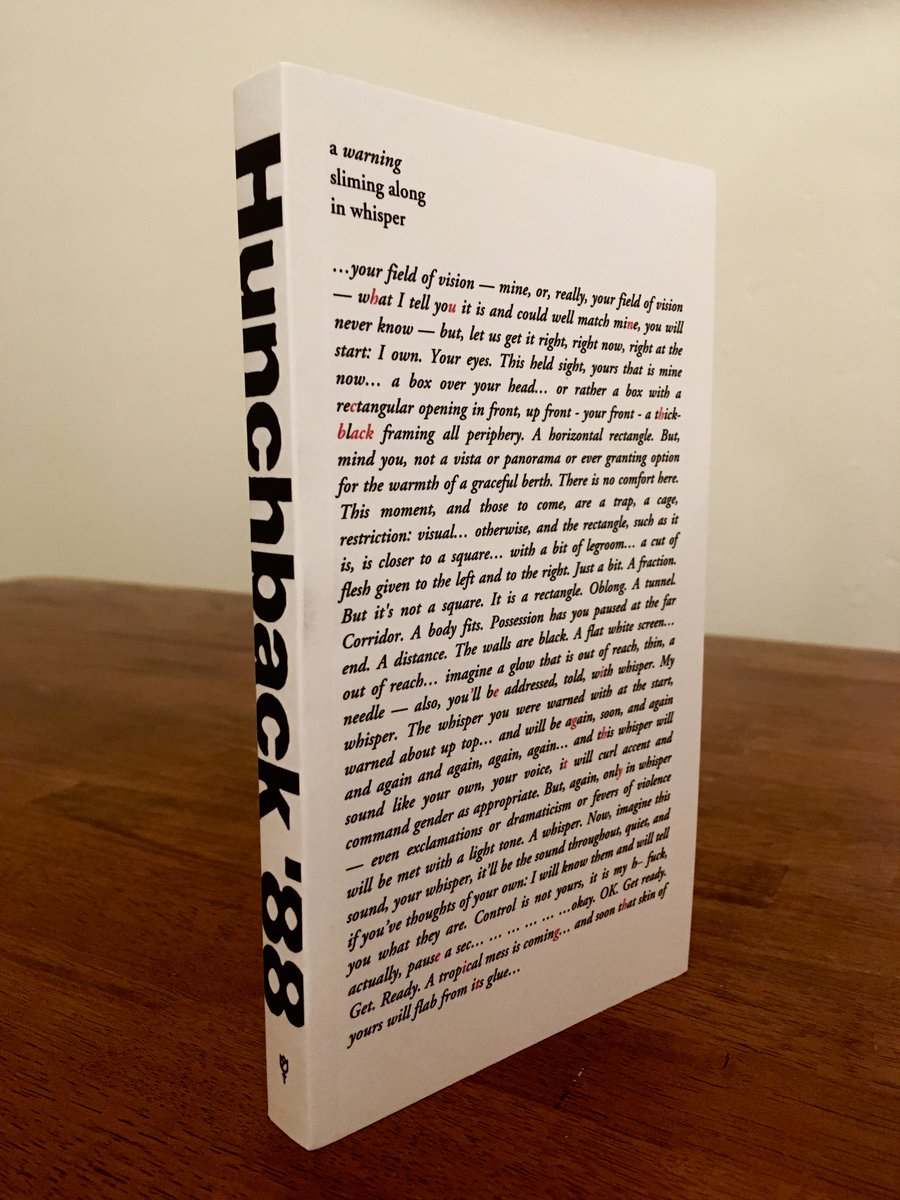

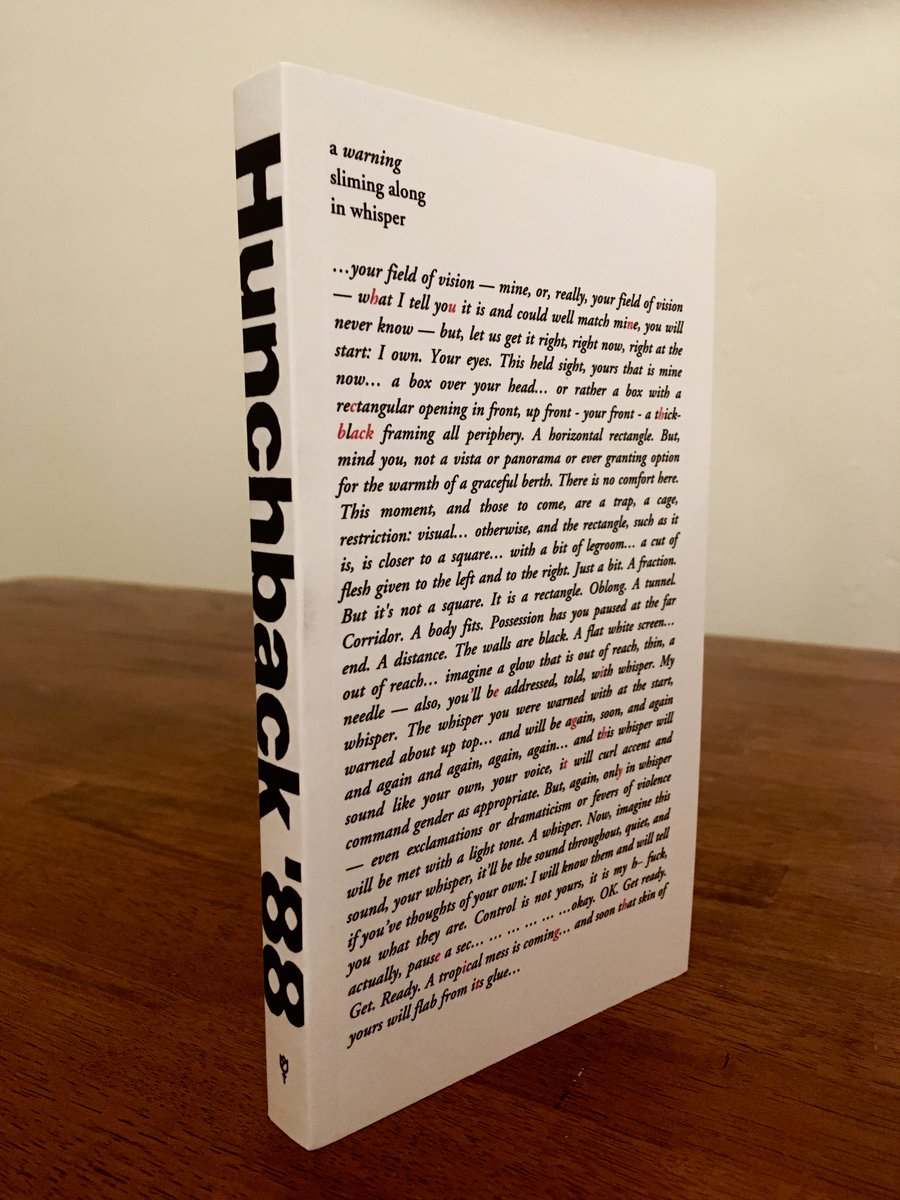

Christopher Norris, Hunchback ‘88, Permanent Sleep Press, 2018.

steakmtn.com/Hunchback-88

Christopher Norris, Hunchback ‘88, Permanent Sleep Press, 2018.

steakmtn.com/Hunchback-88

Hunchback ‘88 is a book... or a novel mirror of haunted house ferox... or a puzzle in no rush to be solved... or a plot dug in ocean mist... or a moment that exists between flesh-stab and blood... or a cannibal moon of terror... or an oozing artifact... or pus to the slasher night... or youth coming apart... or an eye-rolling task of which none the dumb words above help make it sense.

Christopher Norris, the notoriously misanthropic artist behind bands like Against Me!, Atom & His Package, and United Nations, has penned a book about bodies coming apart.

A conceit of incurious criticism is the pat description of music or literature as “cinematic.” It is evident what is implied here. Cinematic music is predominantly instrumental music that unfolds the exhibition of a range of emotions—even something like Riz Ortolani’s soundtrack for

Cannibal Holocaust moves through a spectrum of idyll, brooding horror, and disco—while being suitably deferent to the presumption of an attendant—yet absent—image. Cinematic literature is an earnest effort at not only depicting the necessary human activities necessary to propel the narrative which is the common presumption of cinema, but indulging just enough to be significant in the soft focus of setdressing and atmospherics.

Contrary to the claim that such works are cinematic is the fact that they are only embodying the realms of film that music and literature already occupied as the consulting agents of soundtracks and screenplays. These works are of the cinema. They are not analogous to movies. They have not really learned new things from existing with and after the cinematic era. They behave in a manner by which cultural mediums seek to superimpose themselves on film as gaunt echoes, rather than finding methods for transmigrating the “cinematic” into a never-coinciding location parallel to film, with all of the properties of their own mediums embodying a new form that is neither evocative of film or evocative of literature.

What do we call this thing? Is it new, or just unrecognizable in our contemporary understanding of literature? Such is the hematophagous aftertaste of

Hunchback ‘88, the debut novel of Christopher Norris, published by Permanent Sleep Press in 2018, an exceptional work of literature—a new ilk of cinematic literature—that prompts this unpacking.

a warningsliming along

in whisper

…your field of vision—or mine, or, really, your field of vision—what I tell you it is and could well match mine, you will never know—but, let us get it right, right now, right at the start: I own. Your eyes. This held sight, yours that is mine now… a box over your head… or rather a box with a rectangular opening in front, up front – your front – a thick-black framing all periphery. A horizontal rectangle. But, mind you, not a vista or panorama or ever granting an option for the warmth of a graceful berth. There is no comfort here. This moment, and those to come, are a trap, a cage, restriction: visual… otherwise, and the rectangle, such as it is, is closer to a square… with a bit of legroom… a cut of flesh given to the left and to the right. Just a bit. A fraction. But it’s not a square. It is a rectangle. Oblong. A tunnel. Corridor. A body fits. Possession has you paused at the far end. A distance. The walls are black. A flat white screen… out of reach… imagine a glow that is out of reach, thin, a needle.

I approach this consideration almost entirely through the foil Wayne Booth. I bought Booth’s encyclopedic book,

The Rhetoric of Fiction, in 1999 while working on a research project to develop a primarily verbal methodology for preparing architectural construction documents. My concern was how to crack open the highly controlled pictorial visualization of buildings by capitalizing on the openness of text. This openness could become so unfettered as to be useless, and thus the interest in Booth. He explores the translation of rhetoric into a medium for which it was not originally conceived, that being late nineteenth and early twentieth century novels. And although the classical oratory model of rhetoric has held sway over the discursive structure of literature from the first linguistic constructions specific to the written word until the present, its functionality has changed to meet varying needs. The visibility of rhetoric as a featured mechanism of writing has fluctuated along the axis of time and across the axis of literary forms. It never fully disappears. However, as it moves from application to application, the devices of rhetoric evolve along with us. The project of Modernism rejects the editorial—rhetorically persuasive—voice. Booth asserts that in its stead, “all of the old-fashioned dramatic devices of pace and timing can be refurbished for the purposes of a dramatic, impersonal narration.”

As was my discovery of the intermedium movement in architecture, the absence of some authorial guidance results in something seemingly useless. Or, if not useless, more accurately, it would lack the generally intended effect of its artifice. Booth artfully establishes the variety of ways that rhetorical principles existed formally and insidiously, rather than transparently. “Patterns of imagery and symbol are as effective in

The Hamlet as they are in

Hamlet, as decisive in

Ulysses as they are in

The Odyssey.” This change is significant in the scaling outward of rhetorical effects from the tactical level to broader strategic application of the performance, from the isolation of the representational phrases to the sweeping blur of the presentation. This is an important characterization, a sort of phase change that continues to take place.

The phase changes of rhetoric are not just constrained to the medium of writing however. Transmigration of oratory rhetoric into text wasn’t an accident. Rhetoric is just a formalization of the way our cognition organizes and assimilates stimuli into our emotions or vice versa. It defines the way we use language to persuade. And language structures the manner in which we think. Thus, all expressive works undertaken by humans perform under some rhetorical structuring. And its evolution does not always follow an intramedium trajectory. One of the most significant transmigrations of rhetoric in human history involved the full bloom of movies as a communicative medium. In his

Notes on the Cinematograph Robert Bresson says, “The cinema did not start from zero. Everything to be called into question.” The purely visual tactics of movies are developed atop the rhetoric of literature, atop the rhetoric of oration. These tactics can be analogized and in those analogies are fruitful clues as to how these phase changes take place. But let me first indulge in a brief digression to provide some historical context.

No matter its execution, the structures of rhetoric enable opportunities for tenuous persuasion (control) even in situations that are meant to seem free. My interest is not in the manner

Hunchback ’88 skillfully juxtaposes Booth’s model of rhetoric with the visual rhetoric of film, but how it abandons the traditional rhetoric of literature for a visual rhetoric that would be impossible without movies, yet is only possible back in the form of literature. The movement back from the way images function to the way text functions is not unlike any other translatory action with its loss of fidelity. One must simply be thrilled about that loss rather than lament it, and one must find a way for this thing to come alive in its new skin. Perhaps the most reassuring thing about this notion of visual rhetoric is that, as literary conceit, it is not new. In fact it is much more indebted to the dawn of literature in the 1500s than the commonplace literature of our contemporary culture that is the seventh son of the seventh son of the first maggot on the corpse of Naturalism.

The ceiling.

Feeling harangued.

Decorative tine, once painted white – now chipped from cheap, rusted from time.

No bulb screws into a dump-mangled socket set awkward at the middle of repeating curves and embossed flowers and crusted rounds creased in nubs, rope expressions and dots and slashes.

Every corner – eight total – a tacked juncture of three flats where dust collects dust, mossy and dense; each pulled buckle a tried sum of dead ends and dead zones; death in general, probably.

So, what was happening 400 years ago? An indispensable resource in answering this question is Rosemond Tuve’s comprehensive book

Elizabethan & Metaphysical Imagery. Renaissance poetry was noteworthy and distinct for its significant investment in images. This is different than the metaphorically thematic use of “imagery” we observe in the last 200 years of poetry (after Baudelaire). Tuve describes an image as “the transliteration of a sense impression”. The use of images in Renaissance poetry was a facet of the still-codified and entrenched mechanisms of oratory rhetoric. Images were understood to be aligned with rhetorical principles, “topographia” for instance, the description of a place… or “icon,” a picture cultivated through similitude… had particular gearlike roles in the machinery of rhetoric. Their organization and interaction was governed by the more syntactical aspects of rhetoric, but their contents were lush and indulgent. Tuve:

Modern readers are prone to think, for example, that either ineptitude in narrative or naive pleasure in merely decorative ornament must have produced a long, slow, rhetorically sumptuous description like that of Mortimer’s tower in Drayton’s Mortimeriados. But an artist’s images are not likely to assist the aims we set for swift and faithful narrative of happenings if his intention is that his images should go far beyond naturalistic fidelity in expressiveness and should be part of a design which by its formal beauty heightened the significance of this matter.

This heightening of significance is known as “amplification.” Amplification was the practice of excessive ornamentation in the composition of these images with the sole function of distinguishing them, making them noteworthy in the slosh of text. Tuve elaborates:

‘Why add the ornament characteristic of poetic discourse, when the idea can be more clearly and economically stated otherwise?’ The Elizabethan, I think, would have simply answered, ‘Because it would not be heard.’

Now, to return to Bresson’s point, “cinema did not start from zero.” As written literature for 300 years meandered on an evolutionary path from the rhetoric of oration, so too do movies build upon that evolution in the structuring of its images. Certainly, movies inherit the narrative rhetoric of literature, but they also undergo a more significant phase change with what I would describe as the in-camera rhetoric of their visual composition. These visually rhetorical tactics, although not new in intent, give us a new understanding of the underlying mechanisms inherent to those tactics—whether in speaking, the written word, or the image—and how those mechanisms more elementally articulate our cognition. In our “seeing” something like parataxis made flesh, we begin to understand the rhetorical function of language differently, less in terms of the logic of its argument, and more—in a return to the aspirations of poetry—for its sensory effect. The conclusion of Bresson’s thought, “everything to be called into question,” might seem antithetical to something that did not start from zero, something that has a terrain. But what is called into question is that the terrain cinema was erected upon was not its own, and that coordination of the new over the old will necessarily involve some clever trajectories.

Ecphonesis: The face—glabrous, white, feminine with the creasings of a perpetual scowl over rotten teeth and dead black eyelids—flashes on the screen for 1/8th of a second in The Exorcist. / A sentence consisting of a single word or short phrase ending with an exclamation point.

Ellipse: The camera in Taxi Driver is shifting away from Travis calling Betsy from a payphone to spare us the agony of watching his rejection, but it only heightens the agony. / The suppression of ancillary words to render an expression more lively or more forceful.

Parataxis: In the passenger seat of Michel’s car, the flickering camera of Breathless on Patricia through the streets of Paris, gestures interrupted, quality of light abruptly changing. / Using juxtaposition of short, simple sentences to connect ideas, as opposed to explicit conjunction.

Adjunction: The camera passes over a doffed tuxedo and evening gown strewn across the floor, past a fire in the fireplace, to Roger Moore as James Bond’s awkward post-coital kissing—was Sir Roger capable of anything but awkward kissing?—with Countess Lisl von Schlaf in For Your Eyes Only. / When a verb is placed at the beginning or the end of a sentence instead of in the middle.

Non sequitur: A femur is flying against a pale sky a satellite is drifting against the blackness of space in 2001: A Space Odyssey. / A statement bearing no relationship to the preceding context.

Paraprosdokian: Danny rides his bigwheel through the abandoned hotel corridors in The Shining, weaving, racing across different floor coverings, racing in great loops, into a dead end where young twin girls ominously stand waiting for him. / A sentence in which the latter half takes an unexpected turn.

Enjambment: In a shot of Meet the Parents Ben Stiller nervously leans against a white tile wall chewing nicotine gum, in the reverse shot a skimpy men’s bathing suit hangs from a clothes hanger over the back of a wooden chair. / The continuing of a syntactic unit over the end of a line.

Anadiplosis: Sergeant Nicholas Angel in Hot Fuzz is on the tube holding his Japanese peace lily, and holding his Japanese peace lily on the platform of a rural train station. / Repeating the last word of one clause or phrase to begin the next.

Epanalepsis: As the camera pans in It Follows, through a window a girl in a white shirt and jeans distance is innocuously walking toward its axis of rotation and it continues to pan, across the protagonists Jay and Greg, across a host of other extras, the interior of the building, and pans back out the window where the girl in the white shirt and jeans is even closer than before, still walking. / A figure of speech in which the same word or phrase appears both at the beginning and at the end of a clause.

Diction (Poetic): The nimble camera of Tenebre crawls across the facade of a house, slowly, uninterruptedly poring over every architectural detail, intermittently presenting useful framed views of its occupants. / “Every word is either current, or strange, or metaphorical, or ornamental, or newly-coined, or lengthened, or contracted, or altered.” -Aristotle

Ignoratio elenchi: Fixation on a childhood drawing in Deep Red seems to reveal that Carlo is the murderer, when in fact it is his mother. / A conclusion that is irrelevant.

Alliteration: Madeleine shimmering in a green silk dress in Ernie’s restaurant, Madeleine in a green Jaguar on the streets of San Francisco, emerald green boxes stacked in Podesta Baldocchi florists, Madeleine floating in the green water beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, Jane in a green sweater and skirt standing between two green Podesta Baldocchi delivery trucks, the vaporous green glow of the Empire Hotel sign washing over Jane/Madeleine emerging from the bathroom, the luminous green sheer curtains silhouetting her figure in Vertigo. / The conspicuous repetition of identical initial consonant sounds in successive or closely associated syllables within a group of words. (Or more generally, a way of creating rhythm that is independent of time.)

These examples are free of the greater structure of meaning they serve in their cinematic bodies. They are rhetorical tactics that function like simple machines on their own, as gifs let’s say, aphorisms of the moving image. This is visual rhetoric. The connection of this cinematic imagery to the momentum of narrative is not where its agency lies. The capacity of the image to communicate independently is the true evolutionary clade of rhetoric in movies. It often labors on a completely different suite of agenda items than the verbal aspects of the movie. And this is, on some level, at play in all movies. But so often film falls short of the power available in its visual language, desperately using images to “Chekhov” (verb: to visually foreshadow) later events–conspicuously framing the rifle on the wall above the fireplace, if not lingering on it for a moment–because it is an image necessary to the rhetoric of the tale, not functional independent of the tale as a pure turn-of-phrase.

Certain types of movies traffic more heavily in the primacy of visual rhetoric. Lucio Fulci calls these “absolute films.” And it so happens that many, if not most of them are horror movies. Fulci describes his movie

The Beyond as:

A plotless film: a house, people, and dead men coming from the Beyond. There’s no logic to it, just a succession of images… People who blame The Beyond for its lack of story have not understood that it’s a film of images, which must be received without any reflection. They say it is very difficult to interpret such a film, but it is very easy to interpret a film with threads: any idiot can understand Molinaro’s La Cage aux Folles, or even Carpenter’s Escape from New York, while The Beyond or Argento’s Inferno are absolute films.

I am not asserting that narrative and the Boothian rhetoric of fiction have no role in film—many movies are quite comfortable and productive functioning as visual tales—but that it is beneficial for our understanding of where literature might head to look at examples in which that is not the primary agenda. This is similar to, for example, an astronomer masking out superfluous radiance with a background frame, leaving only the object under observation.

Small grey room. Small. No windows, no observation booth, no exits to be outlined for a mind-map or hiding in plain sight. Total minimalism: a trap. Feels like a trap… Dangling low on the world’s grossest wire from a ceiling of infinite shadow and mystery and plumbing: a bare bulb strikes below-barren light. Under that: a large Formica table. Under that: two wooden chairs tucked and parked across from each other… and those chairs appear to be melting? From the hall they do anyway; thick brown snot covering a lounging skeleton watching itself watch itself. Confidence mirror cracked. Across the room, the other side of the table, against the far wall, a smaller, also Formica-topped, table with one of those old VHS/TV combo units sitting dust, turned on; screen a dark wobbly looking magenta… slight sudden fuzz breaks across it during my short gaze—I blink once, space out, blink again, turn back into the hall and black, look back into the room and… Place my left palm on the red gloss, it is warm, maybe hot, yank away with a shake before the burn can really get tested. Steps start, slow, continue until I’m standing at the first table, between the two sweaty chairs, looking down at a mound of shredded paper cleanly sculpted and peaked in twists of wormy construct. A cone. A small head dunce cap. Next to it: a paperback-sized stack of yellowed papers. I flip the yoked top sheet, which is blank, the next page: The Creamiest Babysitter.

Horror movies are particularly suitable experimental mechanisms because of our low expectations for them. They possess freedom that derives from if not their unreality, then at least their foreignness. One hopes that very few of us know what it is like to awaken on an operating table with a severed head performing oral sex on us (see

Re-Animator (or don’t see it)). Our frame of reference, our threshold of credulity, is not as rigorous. We open ourselves to the visual—the momentary—in the absence of a pertinent larger picture. In that freedom is the promotion of the rhetorical bit and a demotion of causality. If this sounds familiar, it is because it is much closer to the raw ideals of literature, the magic liberty of mere words, that Rosemond Tuve was discussing above. Horror movies are primarily visual in the way they relate information. They are visually rhetorical in the way the manipulate the viewer. They do not typically hinge on information revealed in dialogue, a practice that hinges much more on the traditional application of verbal rhetoric. Because these images are increasingly emptied of their propulsive capacity, they gather their own gravity and separate themselves from the whole. The fixation is on the tactical setpiece. In an interview with Dario Argento, the questioner suggested, “If you were forced to make the choice between an amazing visual effect and a plot point, I imagine you’d always go for the visual,” to which Argento replied, “You’re right.”

If there was a pristine alignment of the arguments that Fulci and Argento are making it exists in

Beyond the Black Rainbow, an almost genreless horror/scifi movie in the tradition of

Scanners. In an interview with Filmmaker magazine, director Panos Cosmatos said of his methodology for the film:

When I was a kid I wasn’t allowed to watch R-rated films but I would spend hours at the video store just looking at the box covers of the horror and the science fiction films and imagining my own versions of them without seeing them. Remembering that time was the inspiration of the film — the idea of making a remembered or imagined film.

This is virtually a template for a film constructed of the visual simple machines described above.

As we move to understand how this visual rhetoric, which is pervasive in the way the contemporary consciousness apprehends information, has moved back toward literature without falling back into its old comfy tropes, it is useful to visit Jose Ortega y Gasset at great length.

We have here a very simple optical problem. To see a thing we must adjust our visual apparatus in a certain way. If the adjustment is inadequate the thing is seen indistinctly or not at all. Take a garden seen through a window… Since we are focusing on the garden… we do not see the window but look clear through it… But we can also deliberately disregard the garden and, withdrawing the ray of vision, detain it at the window. We then lose sight of the garden… Hence to see the garden and to see the windowpane are two incompatible operations… Similarly a work of art vanishes from sight for a beholder who seeks in it nothing but the moving fate of John and Mary or Tristan and Isolde and adjusts his vision to this. Tristan’s sorrows are sorrows and can evoke compassion only in so far as they are taken as real. But an object of art is artistic only in so far as it is not real. But not many people are capable of adjusting their perceptive apparatus to the pane and the transparency that is the work of art. Instead they look right through it and revel in the human reality with which the work deals.

We are looking for a literature that becomes one of vision, not the vision represented by the text, but the vision of the text. We don’t want to see what the text is describing, but what the text is.

Rene Huyghe says in

Art and the Spirit of Man:

We imagine that an art language would inevitably serve to render, in images, ideas as distinct as those expressed by words–a sort of visual literal translation. To begin, the language of art need not in the least be a duplication of verbal language. Actually, art often serves to make up for gaps or weaknesses in writing.

Because text is assumed to stand in for a totality, each bit is assumed to have a greater whole lingering within it. We write the word “lake”, and we are forgiven for not presenting the verbal cartography of its shoreline—for after all, where does that end, at what scale do we choose to describe it, at what magnification of its materiality, tracing every grain of sand with analogies, “This cluster looks like a calyx, and the next like the wet fur on the scalp of a kitten, and the next…” —for not presenting the bathymetry, the temperature distribution, the color temperature of the light reflecting from every angle. And what of the treeline, and what of the summer camp where the counselors let a young boy drown while they were making love? So, we write the word lake. But the single word “lake” embodies all of that and more, an exploitation of what Huyghe describes as the shortcoming of writing, because it is both empty and vast, large and containing multitudes. And then we follow the word “lake” with another word until we have a book. But instead of stringing these full words together across time and space in a gallivanting tale that undervalues the expansive breadth of each word, is it possible that the entirety of a book is the protraction of a single instant, a single image, or flicker of a few frames from a movie, quite similar to the way a geologic timespan is described using our 24 hour clock where humans arrive on the scene at 11:59:59. This may sound like a shortcoming—after all the movie has thousands of these moments strung together in a grand spectrum of fluid titillation—but it is the book that has stopped time, that has crawled inside the instant like into a cave or a fractal to gaze around at its leisure on the fascinations and possibilities of the entire universe of human knowledge contained in that moment.

A bump in the night. That classic moment of versed, well-worn hauntings… Pretty much the first blood in any and all spooky experiences… was to be my warning: Bump. It was night. Left eye slit, the webbed ectoplasm gurgling above me; lustrous and hard and thick and thin. Untidy. Churning. Soft. A ghost, or this ghost, seems like it could be, would be, more substantial than it probably is, but no surprise: a ghost is an illusion, a brain trick… Thousands of tiny muffins cooking in your oven. What is a surprise is how it feels when it licks your skin. Running a soppy purple-white tongue from top to bottom… Cartographic discovery in every fold, stretch and follicle of my flesh. Then, whoa, when it sinks into you? Pressing dead tongue past the dermis to lick your guts or your cerebral cortex or your left femur or your nervous system… and then when the wild sparks from that attention… When they jolly your body? Well, you feel elevated, bigger than alive, bigger than death… Actually, the farthest from dead you’ve ever noticed being… ever, ever, ever… And I wonder why there is not more of it to be had, immediately, in the future, in a memory… And the creamy apparition whispered in maggot flow, …my captors, comedians and comediennes, a most vile degradation…

Think what a film can do in panning across a landscape of detritus in which a variety of significant and possibly allusive objects are embedded, and even utilizing a camera movement that may be allusive (think of, for instance, the camera movement following Henry and company into the back door of the Copa in

Good Fellas and how tropic it has now become). An earnest response to this situation is to admit that text cannot perform the same function as the image and therefore narrows it must narrow its scope. Rather than a high-fidelity novelization of

Texas Chainsaw Massacre, why not an entire book devoted to the moment before Sally falls unconscious, the blackness, and the moment following her awakening.

The passiveness by which the image in movies may communicate is what literature lacks. One cannot idly “show” a messy room in text. One can say “the room is messy” or one can list the things in the room and describe their position. The first is the jaunty nominal mode of contemporary prose. The second, in its precision, is not actually messy. Rosemond Tuve, discussing a similar disconnect painting and poetry, intimated that, “An Elizabethan poet would have accomplished such an effect by an ingenious tissue of magnifications and ‘diminishings.'” This is not dependent on richness of language, but on the mechanics of how it is rhetorically deployed to address the visual, which is dependent on linguistic silence, the mainlining of a sensation. Tuve’s tissue is woven by connotative gravity, but also by the visual disposition of text relative to the other masses of text and to the structure of the poem, and consequently its location on the page. These latter of these broaches what would be categorized as issues of paratext.

One can “make” a messy room out of text.

Gérard Genette, the godfather of the paratext (author of

Paratexts (or originally in French,

Seuils (or “thresholds”))), describes it as:

What enables a text to become a book and to be offered as such to its readers and, more generally, to the public. More than a boundary or a sealed border, the paratext is, rather, a threshold, or—a word used apropos of a preface—a ‘vestibule’ that offers the world at large the possibility of either stepping inside or turning back.

This is “making” a book that is separate from its “writing”.

Perhaps the notion that has the greatest distinction from “writing” is also the simplest, most pervasive, most insidious notion of what is at stake with paratext is the book’s size, or what Genette refers to as its “format”. His archaeology of the sizes of books and their meaning is fascinating, if for no other reason than the articulation of how that size is a product of how many times the sheet of paper is folded before it is cut (quarto, folded twice, four leaves, or eight pages per sheet; octavo, folded four times, eight leaves, or sixteen pages per sheet). But the paratextual function, initially derived from the cachet of devoting more paper to a significant work and less to an insignificant work, is more of a culturally perpetuated notion. There have been all sorts of deviations from this. One could visualize the appropriation of the quarto for a vanity publication as easily as for the complete works of Rousseau. The size of the book affects the manner of our approach to it. Consider the paratextual journey of the small book, which Stendhal rejected as “novels for chambermaids”. Eventually, through the Penguin and Pelican pocket books, publications of more significant works of literature in small mass market formats began to divest the size from its the abject dismissive connotations of cheapness. My copy of

The Red and the Black is a mass market paperback. Take that, Stendhal. Now books are generally found in two sizes, mass market and trade. This simple distinction telegraphs the historical paratextual connotations of size, where mass market books are typically pulpy pap and trade books are conventionally “literature”. These are conventions that can be used imagistically. For instance,

Hunchback ‘88 is in mass market format and from this it inherits the entire contemporary consciousness of schlock literature like Dean Koontz, or what have you. This is not rhetoric in the classical sense. It is not rhetorical even in the transitional sense that Booth describes. It is a visual rhetoric that preys on our shared understandings of culture. Now imagine for a moment all the other characteristics Genette unpacks in his book: cover, typesetting, print quality, inserts (another thing that

Hunchback ‘88 employs), etc. And imagine the fullness of possibility in exploring and capitalizing on each of these and all of these for its rhetorical capacity.

Paratexts inflect the writing, but they are not writing. They are visual. Their productive, communicative use pushes writing closer to this realm of visual rhetoric that is so special to movies. Sonja K. Foss, a scholar of feminist communications, writes that visual rhetoric is at play when, “the creation of an image involves the conscious decision to communicate as well as conscious choices about the strategies to employ in areas such as color, form, medium, and size.” This would imply that the author of a book would need to be considerate of all these issues as the book was being composed. This is rare. One can “will” the experience of a book in this direction, to see the image of the book rather than its contents, through cultivation of distracted reading as a way to engender the visual effect of focus/neglect of focus. It seems that the text would be something that frustrates this strategy. But, just as the phonemes of the horror movie—knife, blood, lifeless eyes—allow it to speak without speaking, the text of a book invested in the paratextual, imagistic experience, is vitally important. Philip Wheelwright, in

Metaphor and Reality, establishes the concept of the diaphor, a type of metaphor whose possibility—its magic—lies “in the broad ontological fact that new quantities and new meanings can emerge, simply come into being, out of some hitherto ungrouped combination of elements”. Where words begin to take on visual qualities as their logical destinies are thwarted… it is impossible to expect that the English language is fully capable of a word becoming solely an image, but the disruption of its beholdenness to discursive meaning, and its marriage with the visual aspects of the book is a step toward that reading performance. This is the visual rhetoric possible in the productive symbiosis of text and paratext.

Perhaps most importantly, the paratext, and its family of possibilities, are completely, 100%, distinct from the mechanics of rhetoric that literature inherited from oration. These are things only possible with the book object. Not surprisingly, this is found being indulged in the early literature of the printed word when the book form was a novelty. Perhaps no other book in the pre-cinematic era of literature so lovingly embraces its bookness, the impossibility of its composition in the oratorical theater of rhetoric, than

Tristram Shandy. Rather than make a fool of myself as an armchair Sterne critic, I will close with the uncanny reclaiming of

Tristram Shandy‘s visual rhetoric by Christopher Norris, and its marriage with the post-cinematic diaphorical prose of the novel you’ve been glimpsing throughout this essay.

Tristram Shandy / Hunchback ’88

…a syncopic fade-to-black about 2/3 of the way through

Hunchback ‘88, black pages, clutching sensation of death and smothering, is a particularly compelling trope of horror movies,

Texas Chainsaw Massacre for instance—a relatively bloodless and rather slowly burning movie—builds to an intermediate crescendo at which the protagonist, Sally (Salleeeeeeeeeeeeey), is driven to unconsciousness through psychological trauma, what she wakes up to, and what we wake up to in

Hunchback ’88 after the syncope, is a third act of almost plotless (relative to the first 2/3) visceral horror, it is a tremendously effective mechanism that propagates the experiential characteristics of the reader/viewer directly with the content and structure of the work… the trope is used elsewhere in film…

Martyrs, Frankenstein’s Army, The Descent, and

House of the Devil come to mind. This is the first experience I have had of it in a text…

Hunchback ‘88 is a book that is cinematic not at the discursive level but at the presentational level. It is not cinematically representational; it is cinematically performative. There is not much doubt that humans will continue their infatuation with the moving image. Although its artifice is sure to change, and is changing already from the static composition of the film to the elective stream of video games and the self-curated fragmentation of social media (stand over someone’s shoulder watching a bunch of Instagram stories and try to ignore its bizarre relationship to Eisenstein’s montage). The mechanics that movies have adopted from literature are maturing into their own entities. Surely this will loop around through culture as everything does, as it has, and what I’ve been interested in here is the mature state of what literature began adopting from cinema 75 years ago, where it stands alone yet again. -

John Trefry

www.3ammagazine.com/3am/how-wonderfully-shall-their-wordes-pearce-into-inward-human-partes-the-new-visual-rhetoric-of-literature-hunchback-88/

Christopher Norris...

who goes by the alias Steak Mtn.,

who has been the artist behind several notable punk album covers,

who is responsible for the visual identity of the band Against Me!,

who does not listen to Against Me!,

who has made art that is permanently inked on people’s flesh,

who cringes when reminded of that,

who once sang in the grindcore band CombatWoundedVeteran,

who is quite ashamed of that fact,

who became notorious in the hardcore scene,

who was relentlessly aped by the hardcore scene,

who has crafted a reputation as a misanthrope,

who works very hard to maintain that persona,

who probably hates you,

who probably hates me,

who is my close friend,

who designed

a book I co-authored

...is now an author in his own right.

Hunchback ‘88 is Norris’ debut novel. It’s not tied to a traditional, linear structure but is instead a free fall of off-putting scenarios, grotesque word pairings, and the deranged brain droppings of an artist who is possibly a genius but possibly also completely insane. There are no chapters or page numbers so it’s easy to feel lost—stranded, really—in the dark recesses of his mind.

Those who have had the misfortune of following Norris and his antagonistic Steak Mtn. endeavors since his CombatWoundedVeteran days in the late 90s may notice a thread of similarity between his graphic design work and his prose. Norris’ trademark artistic style on the covers of albums like Combat’s

I Know a Girl Who Develops Crime Scene Photos was immediately identifiable among its punk peers—a perverse heap of neon limbs, decapitated skulls, blood spatters, and seared flesh. After Norris popularized the style, a number of—to be polite—“similar” works started cropping up on record sleeves and t-shirts, leading you to wonder if they too were original Steak Mtn. designs. But of course, if you had to ask whether it was a Steak Mtn. design, it wasn’t. Norris has always had a way of always staying one step ahead of the trends in hardcore, a perpetual progenitor of provocation.

Norris has been notoriously and deliberately difficult to hire, and even more difficult to work with. He has been sparing with his design services, doing work only for select artists like Atom & His Package, Jeff Rosenstock, United Nations, and the client who has been able to stand him the longest, Against Me!. He is typically blasé and unenthused about the work he’s done, and life in general, but there are glints of real, actual excitement buried deep under his surface-level apathy when discussing

Hunchback '88, which he worked on for six years, mostly writing it on his phone, and largely as a distraction. Maybe his excitement stems from the fact that this book marks the first time he has stepped out from behind his protective Steak Mtn. shield and truly put himself out there.

And so… an interview with Christopher Norris about

Hunchback ‘88...

Noisey: So which of the Harry Potter books would you say your book is most like?Christopher Norris: The ass cabin one. Yeah. That’s what it’s called, right?

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Ass Cabin, yes.A Fun Night at Ass Cabin. I think we’re done. Thanks.

How would you describe the book?It’s a horror book. I guess it’s rooted in horror but I always like things—movies, books—that look like one thing but are another thing. I like people who write below genre. It’s tacky to say they write above it because it means that they’re above it, but below it. So, horror movies that don’t seem like horror movies, horror movies that are smarter than they lead on.

So what does this book purport to be and what is it actually?I’m sure I’ve got plenty of dumb, pretentious things to say about it, but realistically speaking, it all boils down to: I like seeing bodies come apart. And I like writing bodies coming apart.

Much of it feels like an exploration of space on the page, but also, there are sections that are composed of lengthy, complex, really disgusting and off-putting word clusters. Where’d your writing style come from?At some point in time, I thought to start writing screenplays. Not like I would ever make anything, but just to see if I could do it, because I like reading screenplays. I like the skeleton of a screenplay. So then I was like, “Well maybe I’ll write a book that’s just a screenplay.” And then I wrote five movies, essentially.

I liked the idea of writing a book but I always thought, ah I’ll never be able to do it, or I’ll never be able to do it in a way that I want to do it. So I started finding writers that I actually like, because I also don’t read a lot. I like the idea of reading, and the rhythm of words, but I thought I’d never be able to do that. Because even though I have an art background and understand abstraction and things like that, you think, “Who’s gonna have patience for something that’s all fucked up and weird?” So once I started finding things that were similar to movies but in novel form, I was like, oh this could happen. I don’t have to have a three-act structure. I don’t even have to have a fucking ending. Books are way more forgiving than any other art form. You could spend 20 pages describing something that doesn’t really matter.

I notice on the cover you did not put Steak Mtn., you put Christopher Norris. Why?Because Steak Mtn. is so stupid. I think this is the first thing that I’ve ever done that’s not dealing with bands or things like that that… I’m not gonna say I’m proud of it, but it seems more in line with any creative ability that I have or would rather align myself with. Also, Steak Mtn. is a thing that’s gonna follow me around forever, that I’ll never be able to schuck. You name yourself something stupid when you’re 18, and then all of a sudden it takes off and you can’t avoid it. So I didn’t want to put Steak Mtn. on the cover. And Matt Finner, who put the book out, was… I don’t think he was bummed about that but he was like, “Oh, well... I kinda gave Steak Mtn. a book option.” And it just looks tacky, it’s such a stupid name.

If I may psychoanalyze: I think you’ve often used Steak as a veil to hide behind and poke fun at people and things with some level of anonymity. Would you agree?Yeah, 100 percent. Are you kidding me? It’s a hammer.

So is it scarier then to have your name on this? It’s harder than writing it off as just fucking with people, which has been the premise behind Steak Mtn.It would be scarier if it was the beginning of my career, if I was more sensitive to things like that. A lot of it is a little weirder, but for those who know Steak Mtn., chances are they know my name anyway. It’s a little scary, because I don’t know if it’s good, but I know I liked doing it. It’s like most art where it doesn’t actually matter if it’s good.

Who do you think your followers are at this point?Like, 40-year-old hardcore kids and sweaty teenagers.

Sweaty, teen Against Me! fans.Yeah, exactly. And that’s kind of how it’s been for ten years. And most Against Me! fans don’t know Steak Mtn., either.

But certainly they see some congruity between the band’s albums and the merch and Laura [Jane Grace]’s book.You would think. But I don’t know if anybody’s that perceptive. I think if you are sensitive to art and aesthetic and aren’t just consuming it at face value, or you think this looks “sick,” but you don’t create that timeline in your head… I don’t think people are that smart.

How do you think the average Against Me! fan would feel about Hunchback?There’s a version of

Hunchback that’s way sketchier, way meaner, that’s way more… I wouldn’t say sexist or misogynist, but I would say treating sexuality in a really abject, transgressive way, that I pulled out, like a month before it went to press. It maybe made me nervous a bit. It also just felt unnecessary inside of a book that’s full of unnecessary things. Most of it was kind of not very PC sex stuff that makes people nervous. But again, books are different because people will read something fucked up and will not get as super offended as if it’s in a movie or a fucking song by somebody. It’s strange what readers—proper readers who love reading—will take. I like that idea that movie fans or music fans never really wanna get out of their lane, but readers will read almost everything.

I couldn’t believe the lack of depth of the average online reader when I saw the reaction to that “Cat Person” story—people getting angry about a character being called fat and what not.Absolutely. In general, a writer writes personalities and lets them bounce off each other. So, of course if you have a person who sucks, they’re gonna say shit that’s awful. Sure, it’s in the mind of the writer who’s like, “What’s the worst thing this person could be called?” But obviously we’re in this strange culture of… not even knee-jerk, not even trigger-finger. It’s crazy—you don’t even finish the sentence and you’re in trouble.

There seems to have been a movement in recent years of older, artsy hardcore dudes writing books of poetry or dark novels. Do you consider Hunchback above that or is it part of that?It’s part of that because it’s unavoidable. Somebody like Wes Eisold or Max Morton, people who are working in a transgressive manner, I’m definitely writing in that mold. There’s a new term called “horror-adjacent” that I’ve been hearing a lot—horror movies that aren’t horror movies, the artsy horror film. So I think in general, hardcore men and women who are writing these books, they’re obviously like, “I’m in line with that because my interests are like that.” They like seeing bodies come apart, or they like tales of drug abuse, they love [Herbert] Selby and people like that or Peter Sotos. And I like all that stuff too.

Do you think you’ll retire Steak Mtn.?I would love to retire Steak Mtn. I would love to not have to rely on it for money. Let me rephrase. I would love to not have to rely on it for the occasional money. Because I’ve set up Steak Mtn. so that I don’t do Steak Mtn. very often. There are stretches of time where I don’t do work, because I’m either turning it down, or I’m goofing on bands where I take the work, drag them along, and then fucking dump ’em. So sometimes the persona of being Steak Mtn. is more interesting than making the art. So to me, being difficult is the most fun. And I have the option to abuse people in a very PG way.

So being difficult is an integral part of the Steak Mtn. body of work?Always. The whole body of work is about being difficult, and testing people’s limits of what they’ll take from you.

I noticed a parallel between sections of Hunchback and the I Know a Girl Who Develops Crime Scene Photos LP, in that it was this word vomit of well-strung, disgusting phrases.Great.

And even going back to the Amputees art you did, I feel like there’s a real similarity between the two. Do you see that or no?My goal on that work back then, when [Dan] Ponch and I started Combat, we were seeing all these bands, bands that we loved—Crossed Out, Man Is the Bastard, No Comment, even the San Diego stuff like Antioch Arrow and Heroin, fast and loose, crazy grind stuff or jumbled insanity—what we were seeing was a lot of dumb black and white stuff that I looked at and said, “I don’t want to do that.” I want to do that, but I don’t want to put a fucking dead baby on the cover that’s been blown out on a Xerox machine. We’re gonna take that dead baby and we’re gonna give it bat wings and we’re gonna put it on a fluorescent pink background. Because it’s familiar but it’s different. That’s how the work has always been. I’m drawn to these dumb things. I’m drawn to skulls. I’m drawn to dead, idiot things. But I don’t want to do it that way.

After you made a lot of the Combat art, did you see a lot of similarities cropping up in hardcore?I think there’s a lot of similarities but I think also these things happen like zeitgeist. They happen in four different places and you have four different people doing…

Parallel thought.Parallel thought. The brain is complex but it’s not that complex, and the human condition all works with the same details. So it’s not surprising that some idiot kid in Minnesota, and me, and somebody in California, and somebody in New York, and somebody in Germany all had the same idea.

A lot of that Combat art was based on the design for

Pee-wee’s Playhouse. That had a huge effect on me, that insanity, Gary Panter’s design, and that color and that strangeness. And even something as silly as like, the work that Rob Zombie was doing in White Zombie—

La Sexorcisto and all that stuff. He was drawing these proto-Coop stupid devil doll girls on fluorescent green backgrounds with zombie heads.

You and I have talked a lot about using a work to analyze the author’s view of the world. How do you think someone would interpret your worldview through, any of your work really, but Hunchback specifically?They probably would think that I don’t really care much about people. Which is true. I think people would just think my worldview is sour. But also, it’s kind of like this: you’ve got a villain and a hero. And chances are, there’s somebody above the villain that’s a supervillain. The supervillain understands empathy and all the honesty of the world, they just don’t like it. They shit on it. And that’s why they’re supervillains. So I’d love somebody to say, “He’s a supervillain. He just doesn’t give a fuck about the human condition. He wants to take it apart.” Also, I think that somebody would just think that I like fucking with people, because that’s what the book is, too. It’s a mystery that doesn’t need to get solved. Everybody’s so worried about a resolution and I’m not. -

Dan Ozzi

https://noisey.vice.com/en_us/article/7x77ay/steak-mtn-interview-hunchback-88