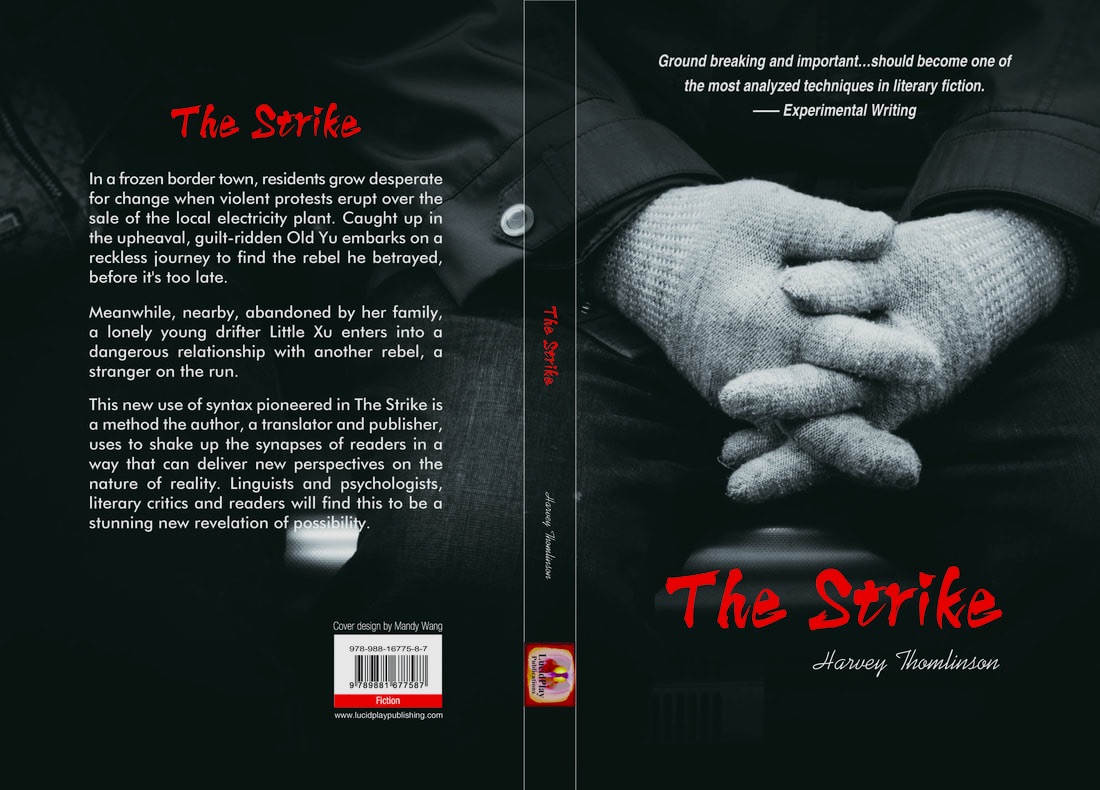

Harvey Thomlinson, The Strike, Lucid Play Publishing, 2018.

Ground breaking and important…should become one of the most analyzed techniques in literary fiction. -- Experimental Writing

This unconventional text while reminiscent of the Dadaists word games, experimental poetry, and William Burroughs's work using cut-ups is, in the end, a unique entity unto itself... -- Ray Fracalossy

The Strike vividly explores a season of crisis in the lives of Old Yu and Little Xu, two outsiders in an ice-bound Chinese border town riven by an illegal strike. Caught up in the upheaval, guilt-ridden Old Yu embarks on a reckless journey to find the rebellious woman he betrayed, before it's too late. Meanwhile, lonely young drifter Little Xu enters into a dangerous relationship with a stranger on the run.

The Strike stands out as a novel that is both experimental and dealing realistically with real world events in an engaged way. The new use of syntax the novel pioneers is a method the author, a translator, uses to shake up the synapses of readers in a way that can deliver new perspectives on the nature of reality. Linguists and psychologists, literary critics and readers will find this to be a stunning new revelation of possibility.

"This unconventional text while reminiscent of the Dadaists word games, experimental poetry, and William Burroughs' work using cut-ups is, in the end, a unique entity unto itself. Don't expect traditional sentence structure or punctuation. A challenging but satisfying novel for those looking for something at the very cutting edge of different." Ray Fracalossy -- Tales from the Vinegar Wasteland

"The Strike, about underground protest in China, which is now OUT from from Lucid Play Publishing in the US. Harvey is best known as a translator of novels by rebellious Chinese writers like Murong Xuecun and Chen Xiwo. His own innovative writing has attracted attention for its adventurous writing style, particularly sentence structures. Harvey also runs Make-Do Publishing, a press which specializes in fiction from Asia." -- Asia Books Blog

"The term “writing” is an archaic thing. What should the new term be? THE STRIKE does not reveal that, but confirms that term “writing” needs to be trashed. We should not be “writing” but crafting tools like THE STRIKE to capture and develop readers that are not afraid to be challenged to think, and that are not willing to again be lulled into the usual dull unconscious pseudo-sleep that what the media calls “writing” leads to today.

Such is the goal of all “big media” today, not just writing, but; THE STRIKE, works as an effective tool to avoid that trap. Every sentence challenges the reader to step up, think, and stay awake. And at the end, the rewards prove to be much more than great. Words prove cheap when describing this book.

The best description lies in the experience, but here’s a taste; “Since his father had taught him as a child to write words until now he came to the river daily.” or, “The old world is falling apart.” Amen, quite true, but these excerpts are just crumbs. Oder the whole meal now; pick up a copy of THE STRIKE." --Jim Meirose, Le Overgivers au Club de la Resurrection

"'Most writers reveal characters’ thoughts and provide descriptions in isolation. For instance, one paragraph will revolve around a character’s feelings and then the next paragraph will describe the setting. Thomlinson, though, takes a more fluid approach, weaving together the external and internal in a single sentence.” -- Kate Findley, Tilt-a-Whirl

“Like that of Gertrude Stein, the writing in Thomlinson’s The Strike ruptures ordinary syntax to create a jarring reading experience.... What emerges is a compelling narrative inextricably connected to its creative telling, replete with a beautiful, poetic layer woven into the experimental syntax.” - Krysia Jopek, Maps and Shadows

The Strike, an experimental syntax novel by Harvey Thomlinson published January 2018.

The Strike is an experimental novel that takes the reader into a different state of consciousness through syntactical experimentation. When a protest breaks out at the electricity works in an ice-bound border town, a retired worker is drawn back into his past and a journey towards the woman he betrayed.

The strike affects a range of characters from hotel sex workers to cops, political fugitives, union bosses, matinee players, corrupt mayors, and border traders. The story grew out of a visit that Harvey made to a Sino-Russian bordertown during a moment of social breakdown that was never reported in the media.

The novel’s new use of syntax is a method Harvey’s used for years to create a kind of idioglossia that shakes up the synapses of readers in a way that can deliver new perspectives on the world and the nature of reality. The aim, though, may be understood as a traditional novelistic one of helping readers to feel the whole world of a novel and the meanings it contains.

Originally from the UK, Harvey is best known as a Chinese to English Literary translator who has translated the likes of Murong Xuecun and Chen Xiwo. Harvey’s translations have been published in New York Times, the Guardian and by publishers like Allen & Unwin. His own innovative writing has appeared in places like Exclusive Magazine (US) and Tears on the Fence (UK). The Strike gained some underground reputation as excerpts were featured in journals in the UK and US but now the whole novel will be available at last from Lucid Play.

Meanwhile Lucid Play has also acquired world rights to Harvey's novel-in-progress The Sentence which takes the experiments with syntax still further and is currently scheduled for publication in August 2018.

Excerpt 1. The Strike

Mrs Zhang was depressed purple leaves scattered along austere avenue because the wind was strong few of her friends were in the park. She came here every morning although this winter was severe to do her exercises required suffering. Walking with her bag of vegetables east of the crematorium there was always a wilderness.

All their group's chat that early morning rusted pagoda turned around the strike. Mrs Liu had heard from her nephew at the Bright Moon electricity plant they reached and stretched. A bird started amid frozen winter foliage Mrs Zhang looked worried remembering long ago violence by the Suifen river.

According to Mrs Liu as the earth moved round the sun the Bright Moon workers had already marched to People’s Square.

Later Mrs Zhang almost flew up seven flights of stairs to warn her husband of many decades Old Yu in the kitchen the television marked time. After moving to this new apartment two years ago light probed weakly from the balcony spring festival ribbons still fluttered.

Old Yu have you heard what’s happening?

These days she didn't know whether he heard things eating soup noodles in their small kitchen they lived often as not.

Excerpt 2. Waking

She was Xu Yue lay on her side to stay asleep the sheets had crawled up her thighs a day yet to penetrate. When her eyes opened she couldn’t breathe sometimes they turned up the heating so high she saw chairs with spaces inbetween.

Across the morning her legs stretched remotely sensations stirred last night’s clothes piled on the bed. Because it was Saturday there was no hurry to move a dirty plate on the floor unless she wanted to. She stayed there lazily enjoying the soft pillow in her mind dusty light sparkled like emotions.

Time pressed these dim paint walls flat as thoughts a dead moth. Across the scratched old dresser she saw emptied out clutter from her bag at the same time her roommate seldom stayed over.

After a while she stood up and stretched with faint hopefulness the gap in the red curtains let in the pale sun.

The light shimmied throughout the twenty-third floor she remembered her nervous client last night at the Far East Hotel. After rejoining the ladies at Jade Heaven they’d all finished a bottle of snake wine laughing at her description of the stranger's anxious behaviour the night had flown by.

She looked out across the misty sea of winter-weathered apartment blocks half a galaxy from her village she lit a first cigarette.

The Border Trader

(Extract from Chapter 12 of The Strike)

He wondered whether he was dreaming. The sticks persisted at nearer intervals in the empty blueness voices. The door sprang open unexpectedly Vladimir and Dmitri were there with a woman he almost called out in a hotel uniform. They faced down the three men at an unconcerned pace vanished through the door mouthing threats.

Vladimir approached the bed was splattered with blood to examine Pytor wiped his eyes. The hotel attendant apologised repeatedly a blow fly settled on the ceiling saying how lucky he was.

“Lucky to be alive.’

The woman left and the three men helped Pytor move his sore leg wasn’t as bad as thought. After a while he was able to pace the room from side to side they examined him. He tried first one leg and then the other according to inclination they directed him. There was a stiffness in the vicinity of his left hip he realised that that the icy streets of the town would be murder.

“We warned you.”

The night before they’d had told him about the trader from Suifen with one leg missing in the hospital over there. He’d been set upon in the icy streets beaten in the snow after the local hospital had to amputate there were always going to be consequences.

“You need something.”

They was snake still fiery in a flask Vladimir reminded Pytor that he’d promised to help his cousin Katya buy shoes. The night before in the Far East Hotel Vladmir had been drunk as a fish chasing slender waitresses behind the bar with bad skin. Pytor decided to go although he’d have to look out for his enemies his head ached and throbbed.

“One for the road.”

On a fine winter morning they descended past the third floor brothel red corridors with naked carvings had kept him awake all night. Late breakfasters ate pickled vegetables beyond the lobby streets white and cold as metal. By the hotel queues of donkey carts and yellow were forming embedded in the ice was black from age. They waved down a cart outside small clusters of languages were thawing out the up and down day.

“The border station.”

The train had just arrived at the station bluely dust releasing a mass of their fellow countrymen and women. As the sky was high in the air hundreds surged onto the frosty street with its engraved hotels carrying red and white striped bags. They stood and waited for Katya few were going the other way until they found her.

“You guys must be blind.”

She was Katya had risen early that morning heading for the train in a snowstorm black pigs riding to the border. Although the world wasn’t breathing she had eaten a boiled egg before setting forth her husband’s feet were warm and hairy. A square blue car was abandoned frozen at the border she crossed twice a year as a buyer for her sister’s small shop.

Hospital Visit

(Extract from Chapter 14 of The Strike)

They held each other nervously Little Hua looked through the door. There she saw a confused space of metal bed frames and tubes trapped her father.

When Little Hua approached her father at first she could hardly believe there was no room to put a chair between the beds. There was the familiar smile of shy pleasure door half open as if he was embarrassed to show feelings.

‘You’re here.’

She wasn’t sure what to say as she sat on the edge of his bed a doctor in a blue gown looked through the door. Somehow she was afraid that she might see something like death in his eyes he cleared more space for her. All her life she’d feared that he would be dead skin and bones before she could make him feel loved he waved his hand.

“Sit with me.’

Selflessly as the others in the ward watched he made room for her in what looked like new black striped pyjamas. There was a pile of peel and shells on the dresser she was afraid to show any emotions that the nurses should have cleared away.

“Nothing, nothing.”

She rose again to clear the clutter he said that it had been a minor stroke sweeping everything into a small bin. She knew of course that several of her father’s family had just dropped dead afterwards she opened her bag before the age of sixty.

“I got cold, you see.”

Family history always played a part apparently he’d fallen ill on a bus she produced the herbal medicines. She’d made a special hospital visit to get these pills that the nurses probably wouldn’t let him use anyway he thanked her quietly.

They sat in silence he’d long hated talking about himself. She loved this modesty of his was not the style now seeing him helpless with all these sick people she would die. While time continued he lay there attached to a catheter they’d always had this mysterious bond.

‘You must get better now.’

As a child he had always protected her when they visited the toilets nights the temperatures yellow icicle-rimmed concrete block were often twenty or more. She’d feel nervous crouching above the frozen hole steam rising as the wind stirred dead papers in the corners her father whistled. The walls and floor were deathly cold to the touch she tried to keep her balance as she shat or pissed. Afterwards she’d run all the way back to their smoky brick room with her father howling ghosts chased her.

Author's Commentary:

‘The Strike’ is an experimental novel set in a depressed factory town in the far North East of China. The novel uses a linguistic strategy which aims to subvert expectations about the correspondence between syntactic and semantic structures.

Conventional syntax shapes the way we perceive reality by encoding conceptual relations, particularly temporal relations, or causality.

She was Katya had risen early that morning heading for the train in a snowstorm black pigs riding to the border. Although the world wasn’t breathing she had eaten a boiled egg before setting forth her husband’s feet were warm and hairy. A square blue car was sat abandoned frozen at the border she crossed twice a year as a buyer for her sister’s small shop.

A key part of the strategy of this novel was to undermine conventional implicatures of sentences, allowing a more complex range of meaning relations to emerge.

I saw this town as being a world where memory and expectation pull in different directions. Some sentences place complements of time and space in ambiguous positions on phrase boundaries.

“With her hair pinned in a scraggly bun she saw everything riding through the dark night of history to pass the time there were adverts on the walls.”

Others do something similar with conjunctions, which play an important role in establishing semantic relations between clauses.

“Their town was standing up although the gates of City Hall remained closed their voices rang out unanswerably.”

In my view, experimental writing should seek new ways to give aesthetic form to subjective experience.

She wasn’t sure what to say as she sat on the edge of his bed a doctor in a blue gown looked through the door. Somehow she was afraid that she might see something like death in his eyes he cleared more space for her.

“Sit with me.’

Selflessly as the others in the ward watched he made room for her in what looked like new black striped pyjamas. There was a pile of peel and shells on the dresser she was afraid to show any emotions which the nurses should have cleared away.

“I got cold, you see.”

As a child he had always protected her nights when they visited the outside toilet block was often twenty or more below. She’d feel nervous crouching above the yellow icicle-rimmed hole as the wind stirred papers in dim corners her father whistled. Afterwards she ran all the way back to their smoky brick room with her father ghosts chased them.

I wanted to create new syntactic structures that were mimetic of the chaos and indeterminateness of the universe of my characters.

- http://exclusive3.weebly.com/flash-fiction.html

One of the most ground breaking and important new developments in innovative fiction writing I feel comes from the new syntax created by writer and publisher, Harvey Thomlinson. This new use of syntax is a method he's used for years to create a kind of idioglossia that shakes up the synapses of readers in a way that can deliver new perspectives on the world and the nature of reality. I was happy to be able to dialog with Harvey about this formally, which can be read below. Excerpts of his unpublished novel have been published in magazines in journals in the UK, and now two are in Exclusive Magazine, with his commentary on them. http://exclusive3.weebly.com/flash-fiction.html I feel when this is published as a whole by some adventurous press ready to take the risk with a novel that is both experimental and dealing realistically with “real world” events in an engaged way, it will become one of the most analysed techniques in literary fiction. I feel linguists and psychologists, literary critics and professors will find this to be a stunning new revelation of possibility. You may wish to follow his website for new developments. http://thestrikeonline.com/

Harvey is most known as the translator of Chinese novelist Murong's A Novel of Chengdu, which was a finalist for the 2009 Man Asia Literary Prize. Harvey also runs Make-Do Publishing, which presents some of the best contemporary writing in Asia. Here follows our discussion.

Tantra:

Your writing style is adventurous, particularly your sentence structures. People so easily take for granted the usual way of writing, grammatically, and Experimental Fiction has the opportunity to shake that up. One of the fascinating aspects of innovative writing is stretching our minds to think new ways, and language is intricately involved in how we think. I feel your use of syntax creates a new language, and it has been proven that people can less their chances of Alzheimer’s if they speak two languages. Your work seems to me to have the ability to make our minds more agile and our experience of the world youthful and fresh.

Harvey, here are some quotes Clifford A. Pickover that I think speak to what you’ve accomplished. I’m curious to hear about your goals and methodology of making the new language structure. These relate to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which says that language structure affects how we see the world.

“Paul Kay, the linguist we discussed who is interested in color and language, agrees with me that language shapes the way we compartmentalize reality. “There is a wealth of evidence showing that what people treat as the same or different depends on what languages they speak.”’ 22

“Today, 438 languages have fewer than 50 speakers. {written in 2005} “With each language gone, we may lose whatever knowledge and history were locked up in its stories and myths, along with the human consciousness embedded in its grammatical structure and vocabulary. . . .” 33

“If language and words do shape our thoughts and tickle our neuronal circuits in interesting ways, I sometimes wonder how a child would develop if reared using an “invented” language that was somehow optimized for mind-expansion, emotion, logic, or some other attribute. Perhaps our current language, which evolved chaotically through the millennia, may not be the most “optimal” language for thinking big thoughts or reasoning beyond the limits of our own intuition.” 77

From Sex, Drugs, Einstein, and Elves: Sushi, Psychedelics, Parallel Universes, and the Quest for Transcendence by Clifford A. Pickover, Smart Publications, Petaluma California 2005

I see what you write as a kind of invented language that expands our minds.

Harvey:

My experimental novel The Strike uses a linguistic strategy which aims to subvert expectations about the correspondence between syntactic and semantic structures. Standard syntactic templates imply conceptual relations, such as sequence, or causality, and as Peter Kay says, these shape the way we ‘compartmentalize reality.’

The Strike is set in a depressed factory town in the far North East of China. The goal of what I call “existential syntax” is really a traditional novelistic one of helping readers to feel the whole world of a novel and the meanings it contains.

Tantra:

Can you describe the process when your sentence methodology first dawned on you, your first inklings of how it would work, your goals with it, and how it developed along the years?

Harvey:

A few years ago, during a chaotic period in my life in Mexico, I began to experiment with writing short pieces of a few paragraphs, and also rewriting chapters of pulp fiction books which I had picked up from second hand English bookstores in Oaxaca and Mexico City.

The Strike was an attempt to expand this to a novel-length fiction. The story is set in a rotting factory town in the far north east of China, where the people protest after their government decides to sell the local electricity plant.

The text generally works with purposeful combinations of phrases, rather than some Burroughsesque random cut up. There was no single method, more a spirit of ‘bold, persistent experimentation,’ but a consistent goal was to destabilise the sentence, the “bolus of meaning,” according to Fregel.

Sentences like the following use a strategy of disrupting the semantic relations that are embedded in syntactical entities.

“Although the world wasn’t breathing she ate a boiled egg before setting forth her husband’s feet were warm and hairy.”

“With her hair pinned in a scraggly bun she saw everything riding through the dark night of history to pass the time there were supermarket adverts on the walls.”

“Somehow she was afraid that she might see something like death in his eyes he cleared more space for her.”

Tantra:

Can you talk about your terminology “existential syntax”? Do you connect it with Existentialism?

“Existential syntax” doesn’t really connect on a theoretical level with Existentialism, except by analogy. It is my term for a set of experiments that share the goal of moving beyond conventional syntax and the term Conventional syntax shapes the way we perceive reality by encoding conceptual relations, particularly temporal relations, or causality.

Phenomenology (of which existentialism was one branch) was partly concerned with describing experience without obscuring the description through misused concepts – hence the analogy.

“Syntax in Experimental Literature: a Literary Linguistic Investigation” a dissertation by Gary Thoms, written in 2008, breaks down Beckett's How It Is, among other things. This novel has a lot of similarities to yours in his particular systematic toying with syntax. Thoms refers to his arrangements of juxtaposed fragments within sentences as “chunking.” This is something you do in your own way. Thom says:

“This is characteristic of Beckett’s attitude to writing: while he believed that language was inadequate for true expression, he felt that the goal of writing was not to free itself from language entirely, as with Burroughs and Cage, but to misuse it with intent.”

You also have your way with words. The world has already experienced Beckett's deliberate misuse of syntax, which plays with time, and is said to be the voice of the eternal present. How would you say your book moves the literary dialogue forward into new ground?

Beckett’s writings are one of the greatest achievements of the literary avant-garde. In terms of formal features of language, the prose of The Strike certainly makes use of what you call chunking, as well as other “Beckettian” techniques such as deletion and elision, and as with Becket there is often a choice of parsing the text into different sets of phrases.

However the Strike also introduces new syntactic patterns. Some experts argue that experimental writing can never truly access linguistic form, because readers simply apply their knowledge of standard syntax to form the most likely reading. This is no doubt largely true, but I wanted to see whether new templates could be established.

Tantra:

And where you see it moving next?

Harvey:

Experimental fiction seems to have lost its ambition to influence a wider literary culture and the whimsical postmodern ethos still dominates, 40 years on. I think that probing at what lies behind “language” is a very important task for a writer, because to return to the point you made earlier, of the large part that language plays in shaping our reality.

At the same time, experimental writing should not be some kind of hermetic game for writers but should aim to create literary forms that deliver a more thrilling aesthetic experience for readers, a sense of something big being at stake.

https://lucidplaypublishing.weebly.com/the-strike.html

Harvey is best known as a translator of novels by rebellious Chinese writers like Murong Xuecun and Chen Xiwo. His own innovative writing has attracted attention for its adventurous writing style, particularly sentence structures. Harvey also runs Make-Do Publishing, a press which specializes in fiction from Asia.

The Strike vividly explores a crisis in the lives of Old Yu and Little Xu, two outsiders in a frozen Chinese border town hit by a traumatic strike. Caught up in the upheaval, guilt-ridden Old Yu embarks on a reckless journey to find the rebellious woman he betrayed. Meanwhile, young drifter Little Xu enters into a dangerous relationship with a stranger on the run.

So, over to Harvey…

For many writers, I suppose, there is an irresistible mystery about the dependency of form and content. When I started to write this story of a strike in a left-behind border town I wanted to invent a new language that would convey to readers this ice-bound world and all the meanings it contained.

This story started when I flew northeast from studies in Beijing after a friend's tip-off that something was going on. This was the middle of the last decade and the talk was of the birth of a new society being forged in the white heat of Deng's revolution, thrusting China forward into a capitalist future.

But the tale less told was about the large areas of the country where the intrusion of modernity was felt as painful. There were rumours of explosive protests and demonstrations shaking the northeast where millions of workers were being laid off from state owned factories, although few journalists made it up there.

What in retrospect seemed like the decisive confrontation had already passed when I arrived but night after night I watched lines of workers march through the streets of this remote borderland. In the icicled dark so frigid that hot water leaking from a burst pipe would freeze within seconds they filled the empty expanses of People's Square. Their banners made plaintively rational propositions: Our wives ask for our salary, our children ask for education, our parents ask for medical treatment.

The main discontent was wages for laid-off workers which had not been paid for months. The town seemed united in solidarity as taxi drivers gave free rides to the protestors and workers lay down on the railroads so that goods could not come in or out. Mesmerised by this apparent irruption of protest from China's unconscious, I ended up staying on for a couple of months in a guesthouse on a vast housing estate which had belonged to a state-owned railcar factory. The estate had hospitals and schools, and my empty guesthouse had once accommodated visiting Russian experts. Most of the factory's divisions had closed; in theory the laid-off workers would continue in perpetuity to receive wages from the shuttered factories, although these were usually far in arrears.

Staying in this place haunted by the equivalents of characters from Gogol's Dead Souls, China seemed like a land riven not only by economic and geographic disparities but by temporal distention; torn between past, present and future.

As I thought about how to write The Strike, I realized that I wanted the form of my story to somehow be a mimesis of my characters' subjective temporal distention. Chinese fiction is often constrained by the straitjacket of socialist realism; the imperatives of a positive outlook, healthy characters, and formal simplicity, eschewing formal experimentation. I had no such constraints - in fact, for me the more experimentation the better. I had written a number of short pieces using experimental syntax but had been wondering if it would be possible to write something longer. I got down the first lines and wrote my way into it from there: Mrs Zhang was depressed purple leaves scattered along austere avenue because the wind was strong few of her friends were in the park. She came here every morning although this winter was severe to do her exercises required suffering. Walking with her bag of vegetables east of the crematorium there was always a wilderness.

Gradually I drew out two plot threads - involving Old Yu, a haunted old man, and Little Xu, a vulnerable young woman - between which wove secondary figures such as the city's mayor, the chief of police, and deadbeat actors.

The dual-thread structure turned out to mirror the syntax of the experimental sentences, which often featured two independent clauses ambiguously linked by connectives which can be scanned in different ways: She was Xu Yue lay on her side to stay asleep the sheets had crawled up her thighs a day yet to penetrate. When her eyes opened she couldn't breathe sometimes they turned up the heating so high she saw chairs with spaces inbetween.

Some people are put off when they read about experimental language. But my belief is that all imaginative writing should try to create 'novel' dependencies of form and content.

My hope is that the syntax brings the emotional drama of the strike alive in a vivid way, creating a sense of something momentous at stake. - www.asianbooksblog.com/2018/02/500-words-from-harvey-thomlinson.html

Experimental: A word which inspires both promise and disquiet.

I once dated a woman who described our relationship as “experimental.” Unfortunately, our relationship didn’t last long enough for me to find out the results.

Translator and writer Harvey Thomlinson describes his new novel, The Strike, about “an illegal protest in a frozen border town,” as experimental fiction which “uses a linguistic strategy which aims to subvert expectations about the correspondence between syntactic and semantic structures.”

What happens when the form of writing is insufficient to express the multi-dimensional world of thought, time, and perception which we inherit? Why, asks this book, should we be limited by tense to understanding a story purely in one temporal space when our lives are lived as a farrago of memories, present perceptions, and future hopes, and fears?

She was Xu Yue lay on her side to stay asleep the sheets had crawled up her thighs a day yet to penetrate. When her eyes opened she couldn’t breathe sometimes they turned up the heating so high she saw chairs with spaces inbetween.Thomlinson’s use of experimental language can be challenging, not unlike listening to the music of Ornette Coleman or an evening of Schoenberg. It took me some pages to begin to feel the melody in the rhythms and to begin to hear a new palette for the construction of tense and syntax.

Across the morning her legs stretched remotely sensations stirred last night’s clothes piled on the bed. Because it was Saturday there was no hurry to move a dirty plate on the floor unless she wanted to. She stayed there lazily enjoying the soft pillow in her mind dusty light sparkled like emotions.

She looked out across the misty sea of winter-weathered apartment blocks half a galaxy from her village she lit a first cigarette.

It is not only the language which challenges the reader. The story—loosely based on a real events Thomlinson witnessed during a trip to the far northern regions of China a decade ago—moves at varying speed, depending on the mood of the characters. Dramatis personae appear suddenly, only to disappear for chapters at a time. Bit players evolve into important protagonists. Key characters evaporate. It is messy, confusing, unconstrained by thinking in specific times, acting in specific spaces, or any form of omniscient narrative momentum—not unlike the way real people live their lives.

When writing fiction in a cultural context different from that of the author, there is always the danger of (mis)representation and cultural appropriation. Perhaps more so in a book which goes to great—often uncomfortable—lengths to interweave the internal voice of its characters and the mentalité of a community into a larger narrative.

And yet perhaps in the universalism of themes (regret, lost love, excitement, self-interest, hurt, joy, fear) there is also something which transcends the setting. These characters exist in a cold, snowy part of forgotten China. They are utterly banal but live in extraordinary circumstances. Perhaps this is what allows the story to transcend the particularity of culture and nationality—and place them in the universality we all share. - Jeremiah Jenne http://www.theworldofchinese.com/2018/03/the-strikes-experiment-hits-the-mark/

Harvey Thomlinson, The Sentence, Lucid Play Publishing, 2018.

The Sentence is an existential ‘thriller’ which features Klaus, a subject who is trapped in his sentence, haunted by memories of a previous existence before the sentence began.

The novel is relentlessly experimental in the Beckettian sense of messing with the implicatures in conventional syntax. Syntactic structures constantly mutate and evolve with the ever-shifting morphology of the unending sentence. But will Klaus escape the clutches of the sentence cops and uncover the mystery of his past crimes before finding a way to redeem himself?

Extract 1. The Syntax of a One Night Stand

On the cusp of the future the sun was lower in the clouds without waiting for the lights Tamasin and Klaus walked coldly from The Full Stop towards the Paragraph. Tamasin stayed a few paces ahead of Klaus plum blossom unfurled time in purple jeans though the tide was out he was aroused by the slender concave of her knee conjunctions. The glass construction was twenty or thirty stories metal balconies layered sandwiches mostly empty as the ship hadn’t docked yet afternoon filled the yard like dead flowers. Outside the gate of the Paragraph stood a two-storey clubhouse with a domed roof he watched her wait for him there the sky unfinished. Three towers stood within the yard gold and glass constructions seemed like they would be hot in this summer made of cheap materials he foresaw the sky would soon wear off.

The Paragraph gatekeepers still hung around apparently there weren’t many subjects in residence as she passed them a crane swung into action. They seemed to have nothing to do although the crane was unloading a container of words the gate swung open with a push a cloud moved before the sun. He followed her at a steady distance as if reserving his options they stared at the crane with obvious hostility gulls circled on the far side.

They walked across the yard still a broken shard of sun was lobbed into the first construction nearest to the gate luckily there was no one around. The new building lobby appeared recently finished he saw dust scattered like moonlight and uneven grouting in the past she must have summoned the line break. She’d probably had previous encounters with subjects she met at the Full Stop the break ascended. There was no mirror inside the break moved although it was lightless here she didn’t remove her shades. The two of them alone inside the shimmering grey walls increased the tension as they rose through the Paragraph he realized it was night again behind her lids.

The walls sprang open with a hint of drama she opened her eyes through a corridor window the day slid into the sea. Her clause was the first on the left a flock of drowned gulls coming from the break at this time of day in her yellow purse she felt the key. Klaus sensed she had not lived here long as the key fumbled in the space time lock his stomach churned with a mixture of seaweed and foam.

Her single clause was sparely furnished with one red leather hyphen in the afternoon light threaded a shady balcony in the corner he advanced instinctively a red quotation mark flapped from string. Klaus was drawn outside for a few seconds stormclouds arched the bay intermittently a periscope approached them from sinister angles. She tracked him down confidently in the yard below a gardener collected detritus of words apparently the last storm had caused devastation. A finger string moved him back within her spartan clause the red hyphen was a lone furnishing. They were a subject group now and she was without any words clutching him so passionately other constructions seemed to fade away.

Do you know me?

He didn’t really know her but active and passive constituents were coupling. She held him tight in ineluctable sequence her lacy front opened to the sea without being asked. Her mahogany skin felt infinitely porous from shore to shining shore he traversed its curves and ridges.

Much of the light in her clause came from a metal chandelier intricately warped and sculpted she pulled him into her.

Extract 2. Escape from The Sentence.

He reached the corner of the clause and there was the sentence in all its prolific glory, in all its full flow. In this bustling scene its predicates proliferated. Clouds blew, streetlamps illuminated. Trees breathed, subjects came went. The clouds in the sky, the streetlamps in the street. The sun in the light years. Clauses joined to each other at corners with barely a conjunction to show where each began or ended. He realized both the endlessness of his sentence and how far he must go to shake off its surly bonds. He only hope was to find a hole. He still thought that this sentence must be full of them. Wormholes. Blackholes. Mouseholes. Plot holes.

Are we not drawn onward, we few, drawn onward to new era?

Left the sentence went. Right the sentence went. He knew left. It wound around to the front of the Scriptorium. It rambled discursively in the direction of everywhere he had ever been. He already knew there was no escape in that direction. Not unless his sentence was a palindrome.

He went right. He went into the unknown. He already knew he wouldn’t easily escape from the sentence. It wouldn’t be so easy to slip the sentence’s leash.

He must be patient. He must be persistent. He would remain undaunted, he would stay undeterred. He would, he would, indeed, in thought, he would.

Klaus had never been this way before. He needed a new map.

He kept thinking the hole in the sentence might be just around the next Each time the sentence just Around the across the along the above the beyond the

He kept going.

He would keep going for as long as he needed as long as

he believed there would be a hole

Sometime he would sense the gap in the sentence and start running along eagerly only to find // a caesura.

He would throw himself at the and allow himself to feel expectant for a moment heart in mouth as he fell through disappointed // to the other side.

To read more of Harvey's work: The Stand Magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.