Donald Newlove, Sweet Adversity, Avon

Books, 1978. / Tough Poets Press, 2019.

Sweet Adversity is easily one of the

most ambitious American novels of the last fifty years. And if you

weren’t reading new American fiction back in the late 1970s, you’ve

probably never heard of it.

The only edition of Sweet Adversity

ever released came out as an Avon paperback in 1978. Avon editor

Robert Wyatt and author Donald Newlove agreed that Newlove would edit

his two separate novels, Leo & Theodore (1972) and The

Drunks(1974), into a single volume for this paperback release,

recognizing, as Newlove wrote in his “Author’s Note,” that “The

story loses scope and focus when halved into two books.” Newlove

went so far as to say that he considered the original texts “now

forever CANCELLED.” And Wyatt deserves special credit for

convincing Avon to go to the additional expense of having new type

set for Sweet Adversity rather than simply photographing the hardback

texts.

But, as, effectively, a paperback

original in a time when that was publishing’s equivalent of a

“direct-to-disc” movie, it meant that no major paper or magazine

reviewed Sweet Adversity.

And so what is already a heart-breaking

book itself became something of a tragedy as it quietly vanished from

the bookshelves with scarcely a notice.

And one might just leave it at that.

It’s not the only good book to get forgotten, as this site

continues to demonstrate.

But this book, for me, is something of

a special case. For in writing Leo & Theodore and The Drunks,

and then revising them into Sweet Adversity, Newlove achieved not

only a remarkable artistic feat, but also an act of great personal

strength, part of his recovery from decades of alcohol abuse.

In his memoir, Those Drinking Days:

Myself and Other Writers writes that Sweet Adversity “sprang from

my life’s earliest memory–my father dipping a kitchen match into

a shot of whiskey and raising it out still burning.” Or, as

captured at the very beginning of the book:

In a Riply bar he shows them a magic

trick. He dips a lighted kitchen match into whiskey and lifts the

blue flame out of the shot-glass unquenched. Marvel at the

blue-dancing spirit on the glass!

Alcohol makes its appearance on the

first page of Sweet Adversity and, from that point on, it is the

dominant presence in the story. Dominant, that is, with the exception

of Newlove’s protagonists, Leo and Theodore.

Leo and Theodore are Siamese twins,

joined at the waist by a short band of flesh, blood, and nerve

tissues.

Now, for many would-be readers, a

600-plus page novel about Siamese twins–particularly one coming out

at a time when Tom Robbins, Richard Brautigan and Kurt Vonnegut were

among the hottest names in new fiction–must have seemed like some

kind of over-the-top fabulist work, full of exaggerated characters

and absurd situations.

Instead, this is one of the most

realistic books you’ll ever read. Almost too realistic, at points.

“Nowhere has the green or red bile of hangover, piss, bleeding

assholes, and d.t.’s been so carefully catalogued,” according to

the Kirkus Review’s assessment of The Drunks.

Although Leo and Theodore are Siamese

twins, almost no one in the book treats them as freaks–not Newlove

and most certainly not their mother, Stella. Newlove notes, in a

hundred different passages, subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which

their connectedness affects how they live and perceive the world, but

it is never his focus.

The narrative arc of Sweet Adversity

very much follows that of the two original novels. In the first half,

Leo and Theodore grow up in and around Cleveland during World War

Two, discover girls and sex, learn to play instruments and fall in

love with jazz, and witness the lovely and horrifying effects of

drinking on people around them. And in the second half, they come

hurtling down through all the ravages of alcoholism–the black-outs,

vomit, unexplained bruises, lost jobs, seedy rooms, and shakes–until

they hit bottom and begin to lift themselves back up with the help of

Alcoholics Anonymous.

The first part of the book is a giddy

celebration of the fine and destructive aspects of mid-West,

mid-century American life. The boys work as soda jerks, take midnight

swims, learn to smoke, make out with girls in the back of cars, sneak

into movie theaters, fantasize about fighting Nazis, and watch their

mother get punched by their alcoholic step-father. The raw energy of

the time bursts through in Newlove’s prose, as in this portrait of

a busy night at the soda parlor:

Racing with the moon! the juekbox

boomscratches. Fulmer’s splits with smoke after King James cracks

tiny Lakewood on the Friday night gridiron. Car herds roar Third.

Fevered twins set up orders, spirits pitchforked. White-eyed Helene

and Joyce wait table in a blue burn of uniforms. Wayne yawns in the

back kitchen, roasting peanuts, steps out into the squeeze for

tables, cries in the jukeblare, “Swill, you swine!” and goes back

to his roasting oil.

Newlove’s style draws heavily upon

James Joyce’s word-fusing (“the snotgreen … scrotumtightening

sea”), and there are times throughout the book when the frenzy of

the prose becomes close to unbearable. When I call this one of the

most ambitious American novels, I don’t mean to suggest that the

author’s technique always kept pace with his ambition. The worst

comes somewhere in the second helf, when Teddy loses a tooth in the

second half, and Newlove subjects us to page after page of lisped

dialogue (“There’s thill a double order of chop thuey in that

roach.”). It might be realistic but it isn’t interesting reading.

For all the over-sexed,

over-adrenalined dumb teenager things Newlove has Leo and Theodore do

in the first half of the book, there is never anything else than

endearing and touching about the boys. Which is why reading the

second half is such a heart-breaking experience. As he describes in

Those Drinking Days: Myself and Other Writers, Newlove knew

intimately the humiliations and illusions of a hard-core, long-term

alcoholic, and the twins are not spared many of these. The New

Yorker’sreviewer was not alone in considering this novel “probably

the most clear-eyed and moving—and certainly one of the most

honest—books ever written about alcoholics.”

Even with the editing Newlove did for

Sweet Adversity, the book suffers from the intensity of the prose.

Those Drinking Days, Newlove writes that, “The published volume was

light-filled to bursting, enormously lively,” but adds, “and, for

most readers unreadable without great attention to every syllable.”

And perhaps this is one of the reasons why Sweet Adversity has been

forgotten.

If so, it’s a lousy reason. An

occasional word-glutted passage might deserve having a few points

shaved off Newlove’s score, but given the unbelievable energy,

passion and power of Sweet Adversity, there’s no good reason for

this book to have been dismissed as a failure, and certainly not to

have been so unfairly neglected. Donald Newlove and his twins are

among the great fiery phoenixes in American literature.

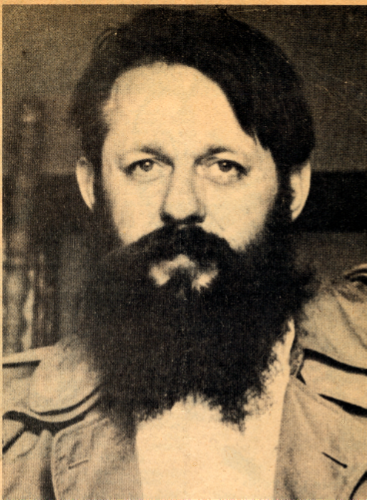

Donald Newlove is the author of Leo and

Theodore and The Drunks, novels published by Saturday Review Press in

1973 and '74, respectively, and republished together in paperback as

Sweet Adversity by Avon Books in '78. These works tell the story of

alcoholic Siamese twins who play jazz in trad bands in the '30s, then

arrive on the Lower East Side of New York in the early '60s. One of

the two -- Theodore, who also stutters and walks with canes --

decides to enter a 12 step program and sober up.

Hilarious, gut-wrenching, verbally

lyrical and very well received when they first were issued, these

books are now out of print and rather hard to find, as are Newlove's

other novels: The Painter Gabriel, Eternal Life, Curanne Trueheart,

and his "life study" Those Drinking Days: Myself and Other

Writers. His celebration of dialogue from novels and the movies,

Invented Voices is still available (from Henry Holt); he's also

written First Paragraphs, selected from world literature, and Painted

Paragraphs, about descriptive prose.

Newlove lives in Greenwich Village --

within sight of the Jefferson Market tower that's on the cover of

Eternal Life. On the day of the JJA on-line chat he was on Cape Cod

-- but anyway, he said he was reluctant to go on-line, that he's not

been impressed by the level of discourse and fears being further

distracted from his main activity, writing. But he didn't mind if I

wrote up some notes.

"I can only think of about three

examples of writing that works as music," Newlove said over the

phone. "Kerouac's The Subterraneans reads like bop prose, which

proves to be pretty hard to sustain. The first three or four pages of

it sound like Lester Young playing saxophone -- the long run-on

sentences. Of course Kerouac was conscious of that.

"Then there's an excerpt from

Joyce, the chapter in Ulysses that begins 'Bronze by gold steely

ringing." It's about a waitress in the window of a cafe, who

hears a horse going by; that phrase describes the hoof irons. There's

also the novel Napoleon Symphony, by Anthony Burgess: that imitates

music. But a reader's interest in such imitation drops almost

instantly.

"With Joyce, you go along with it

for the many rewards. With Jack -- well, I was there when it was

published, so the novelty of it and immediacy kept me interested. But

he only created one character, Dean Moriarity in On The Road, and

that was it. None of his other books have a Dean Moriarity, you know?

"Maybe giving the sense of music

is easier in poetry. . . Vachel Lindsay's 'The Congo,' with the

stanza endings 'boomlay, boomlay, boomlay, BOOM!' -- that's nice! I

memorized that when I was in ninth grade."

Newlove has just finished revisions on

his next novel, The Wolf Who Swallowed The Sun, which isn't yet sold.

Is he still involved with jazz? Sure! He also keeps his trumpet at

hand -- and played a few bars of pure melody over the phone at the

end of our conversation. -- Howard Mandel

Donald Newlove, The Wolf Who Swallowed the Sun: A Jungian Fable of Family and Finance Across the Twentieth Century, Tough Poets Press, 2019.

An enthralling and unorthodox dark fable, full of intrigue and comedy, and with a healthy dose of romance and sex. Written in 1998 but never before published, the novel is a sweeping saga of one family's greed, extortion, and double-crossing as they strive to acquire a controlling interest in the world's wealth. It is also the story of Billy Baxter, heir to this massive fortune who, with the help of a married couple of Chinese-Swiss Jungian psychiatrists (one of whom he has fallen in love with), seeks atonement for his family's sins. Oh, and he also happens to be a wolf.

I've read a lot of quirky, unorthodox fiction in my time and I can say in all honesty that I've never come across anything quite like Donald Newlove's The Wolf Who Swallowed the Sun. But, then, what else should I have expected from the author of Sweet Adversity, a masterfully-executed 600-page seriocomic novel about alcoholic Siamese twin wannabe jazz musicians?

Subtitled A Jungian Fable of Family and Finance Across the Twentieth Century, Newlove's darkly comic novel, originally written in 1998, is the sweeping saga of one family's greed, extortion, and double-crossing as they strive to acquire a controlling interest in the world's wealth. It is also the story of Billy Baxter, heir to this massive fortune who, with the help of a married couple of Chinese-Swiss Jungian psychoanalysts (one of whom he has fallen in love with), seeks atonement for his family's sins. As an added twist that only a first-rate storyteller like Newlove could credibly pull off, Baxter also happens to be descendent from an ancient clan of humanoid wolves on the brink of extinction. -Rick Schober

www.kickstarter.com/projects/1860098210/another-unconventional-literary-gem-by-donald-newlove

Donald Newlove, Eternal Life: An Astral Love Story, Avon Books, 1979.

Donald Newlove, Those Drinking Days: Myself and Other Writers, Horizon.

Who can resist the charms of literary tavern-talk, golden tongues loosened by the grape, etc.? Newlove can--to him it's all ""Drunkspeare,"" to him the pickled greats are ""grounded angels, each at his own uttermost extreme of Little Dreamland, waiting for that healing mist to settle on his cells."" From whence comes this chapped Inquisitor? From 25 years, to hear him tell of it, of booze down the throat, of self-deceit (""I lived in a stupor of guilt. . . during unguarded moments [I] would spot a disappointed hound in my eyes""). Child of alcoholic parents, Newlove sopped up his first bibulous education in upstate New York via the advertising and editorial pages of Esquire (""That magazine--it came poached in vermouth""). Hitches in the armed forces during the Fifties were both lightened and deadweighted by the accumulation of one after another ""Drunkspearian"" unpublished manuscript; marriages and children went by the by; and Newlove's body and mind steadily ""horripilated"" away. A long paragraph of mental and physical deficits is toenail-curling, as is a nightmarishly immediate recounting of the demonically-inviting but impossible process of writing while lit: ""This is it, I'm stuck at retightening unsprung sentences if I want this paragraph tuned like a Rolls. Something chokes and suddenly I'm all over the page fighting breakdown."" Anyone familiar with Newlove's fiction knows his almost buoyant capacity for shame--here, smacking his mother around when they'd both had too much; trying to review books that booze didn't let him first read; ""Stalinism"" against the less resolute, while early on the wagon. But when, in the book's second section, he goes after other famed ""Little Dreamland""-ers--Robinson, Lowry, Kerouac, Jack London, O'Neill, Lewis, Berryman, Lowell, Tennessee Williams--your first reaction may be to stand back. ""Genius is no excuse for self-destruction. . . the illness is ego, with its intolerance, hatred of change and resistance to getting well, grandiose talk and behavior."" They would have all written better sober, Newlove hasn't a doubt. Narrow and starchy? A little--but having put himself already primus inter pares in the failing, Newlove's curt judgments are never easy to dismiss: they've got a survivor's zeal. Add to that the popping prose, the excitement of the resurrected, and you've got a book bound to make any reader more than a little uncomfortable--which is probably its very aim. - Kirkus Reviews

YOU like the note of cheery nostalgia and companionship in the title of Donald Newlove's ''Those Drinking Days: Myself and Other Writers''? Come closer and feel the knuckles of his prose split the lip of your delight. ''About midnight I'd get a second wind at the typewriter and ride a red wave of vino into the city silence. About three in the morning a page snarls hopelessly. I'm all tangled ankles, haggard with wrong words. Surely five minutes rest will clear my mind, then I'll get the nits out of these snarls and go to bed. I melt into the kitchen linoleum for five minutes, planning to get up refreshed, hit that sentence and breeze off to bed. At six or seven in the morning I detach my crusted cheek from the floor and in the mirror eye my waffled new face, some dented, misshapen Dane weighing his fate. I don't see a drunk. I see a beast in the first-light.''

Yes indeed. Donald Newlove, the lyrical novelist who wrote ''The Painter Gabriel,'' ''Sweet Adversity'' and ''Eternal Life,'' is by his own agonized confession an alcoholic who used to wake up ''with a Zulu spear through my brain and eyes like carpets the wine has dried in.'' He drank for about 25 years, spent some five years getting sober with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous, and has not touched booze for almost 10 years. A Scribe for 'Drunkspeare'

He is here to tell us in ''Those Drinking Days'' that as long as he was writing under the influence of alcohol he was nothing but the scribe for a character he calls Drunkspeare, who ''fed in a naked boneyard, gnawing away with an eye for the toothsome maggot, and grew strong on horror - a fearless seeker of the ugly and loathsome, to confirm his power to drink up the worst that life could offer.''

Mr. Newlove writes that he didn't intend ''Those Drinking Days'' to be a lecture, except to himself. But my goodness! He does shake a finger thither and yon. Of Jack Kerouac's career, he writes ''that the greatest writing is made out of loneliness and despair magnified by booze is an idea for arrested adolescents.'' James Joyce's ''Finnegans Wake'' is ''a great bubble of ruby-red exhalations of spirit, and Joyce himself, in Ellmann's great biography, examples the classic evasions, self-deceits, and symptoms, including his brick-red drinker's face and death by ruptured ulcer.''

Of Hemingway: ''Crazy folks shouldn't drink, it's like throwing gasoline onto a banked fire.'' ''For my money, his books go straight downhill after 'A Farewell to Arms' and 'Winner Take Nothing,' aside from the magnificent reprieve of 'The Old Man and the Sea' and most of 'A Moveable Feast.' '' On Faulkner: He ''had a writing peak that lasted for about eight years, during his thirties.'' ''He wrote for twenty-two more years, but his brain was stunned - not that you could tell it by looking at him. What we get from his later decades is the famous mannered diction, senatorial tone, a hallucinated rhetoric of alcohol full of ravishing musings and empty glory. Dead junk beside the cloudburst pages of his thirties.'' Act of Self-Therapy

Well, I'm not about to pick an argument with Mr. Newlove. His book is too courageous and dazzling an act of self-therapy to quarrel with. If I were to ask him for the less glamorous reasons he took up drinking - or if I were to note that he always seemed to go on his worst benders whenever he got near his mother - he would simply cite the passage in which he writes, ''After long exposure to the soft punch of alcohol, drop, drop, drop, drop, drop, the original reason for drinking gives way to the craving: you drink because you want it and need it, drink because you drink. No alibi is needed, either medical, artistic or religious: the illnes is ego'' - '' diseased, alcoholic ego.''

All the same, one almost envys how much Mr. Newlove has been able to put into his bottles. To say that ''you drink because you drink'' makes for a wonderfully absolute view of human behavior. His powerful and frightening book persuades us that the main point for an alcoholic is to admit his or her affliction and forswear liquor. But ''Those Drinking Days'' also makes us wonder if there isn't something to learn about yourself after you've given up drinking. - Christopher Lehmann-Haupt

Donald Newlove, Curranne Trueheart, Doubleday Books, 1986.

Self-conscious wisecracks and barely credible incidents aside, this plunge into the mind of a madwoman thoroughly engrosses the reader. Initially, it seems that thrice-institutionalized Curanne will find her way back to sanity by marrying Jack Trueheart and bearing his child, and that when Jack stops drinking he will give her the help she needs. But his love for Curanne, even when she betrays and slanders him, blinds him to the charade she is acting out of faithful wife and caring mother. Her fantasies are immense: incest with her father, drowned long ago; lesbian affairs with her sisters, her mother, even her child; transference to her baby of her tortured desire to be free of responsibility. As reality becomes increasingly unbearable for her, Jack tries frantically to save Curanne, and the last several chapters raise a masterful curtain of paranoia, ending in tragedy. This book is justified in the risks it takesit may not appeal to every reader, but will dazzle those willing to persist. - Publishers Weekly

Long, riffling, energized, irrepressibly lyrical, a new slice of Newlove's fictional universe of human damaged goods. Jack Trueheart is a guttering 50's-era newspaperman and unpublished novelist--a drunk, too--living with his mother in the tiny upstate New York town of King James. In the library one day, he meets Curranne--a sort of local legend: who as a girl had a spectacularly public mental breakdown; and who has broken down more thereafter, between two marriages, two sets of children. Who this day in the library has returned to live with her mother, having been released only a day before from a Washington, D.C., mental hospital (where she got to know Ezra Pound, picking up some of his loony economic theories, which she personalizes into an obsession with Nelson Rockefeller, who is sexually dominating her through the use of brain waves). But, even in this barely mended state, the day she encounters Jack turns out to be a banner one for both; they find their ""cracks match."" Whirlwind sex leads to pregnancy and marriage: Jack stops drinking, goes to A.A., loses his newspaper job but finds himself scrambling with new confidence, fortified by Curranne's whacked-out courage and unflinching honesty. The novel's first half--Jack and Curranne's first months together, crises and soothings--has the upthrust of a wave; the improbability of the couple is its sanction. Jack and Curranne fight, make up, worry, fear yet allow each other no easy illusion, no sense of superiority; the birth of their daughter Avon rings additional biological/psychological changes on the two of them, fragiley terrifying. Then this idyll-of-ordeals is interrupted by a middle section in which are introduced some vaguely mirroring other characters: among them Leopolda, an ex-alcoholic like Jack but also a trained therapist, who institutes a local group-therapy circle (including some halfway-house patients from the nearby asylum). The pages aren't successful; they bog down in clinical-session dialogues that are too mazey, too much the water-wheel wordiness that is Newlove's Achilles' heel as a writer. It passes, though--and Curranne's fated tragedy proceeds. The long fights against her devils (she's one of fiction's most attractive examples of the dignities and talents of madness) come up ultimately empty. Jack's own sad-sack equability can't save her, nothing can--and she descends (literally) once and for all. Pathos but not sentimentality is sovereign here--but the book seems as impressive for its poetic stamina (Newlove will throw away sentences other writers build whole chapters around), its air of utopian daze, and its paradoxical vision of the success of failure. - Kirkus Reviews

Donald Newlove, Helen's Ass Strikes Homer Blind!, 2011.

As with Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, this work challenges us to understand genius. Helen’s Ass Strikes Homer Blind! tells of the élan vital of genius as seen in Newlove’s two late friends, both geniuses — poet Jack McManis and Dr. Nathaniel David Mttron Hirsch. Inspired verse fills the first half of this short work while the second half lifts off into scientific and philosophic rapture unlike that in any book you may know. It first follows Jack’s daunting recovery from alcoholism and sobriety’s fresh charge to his verse. Dr. Hirsch, author of Genius and Creative Intelligence, reveals the propulsion of human genius through the genes. His unpublished trilogy on Metabiology grounds itself in the meta-consciousness of the human spirit lodged in the genes and the incline that bears it forward like a Bach fugue.

Essential Newlove

No easy choices here. Newlove has five main fields: Novels about art and artists; writing guides for writers and readers; a trilogy of Hollywood novels; autobiography that focuses on alcoholic writers and recovery from alcoholism; and a work on philosophy and metabiology. Our offerings in the Handbook series and the Hollywood novels are described on separate pages (see tabs under Newlove’s link above.) Otego Publishing also currently offers:BLINDFOLDED BEFORE THE FIRING SQUAD, OR THE BROTHERS KIRKMAUS

A LITERARY TREAT from start to finish. Blindfolded Before the Firing Squad, or The Brothers Kirkmaus bares the lives of the brothers Fyodor and Rogo Kirkmaus, long time reviewers for Kirkus Reviews, the book review journal read throughout the English-speaking world.

Rogo and Fyodor write novels themselves, often in the tones of Leo Tolstoy or Fyodor Dostoevsky. But they support themselves reviewing weekly stacks of galleys of forthcoming fiction and non-fiction. The years have gone by and for a memoir with this book’s firing-squad title the aging brothers rake through decades of their reviews and write the very pages of Blindfolded Before the Firing Squad as you read them. The reader swims in early real Kirkus reviews of Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, Tom Wolfe, William Faulkner, Margaret Mitchell, J. D. Salinger, Joyce Carol Oates, Stephen King, Robert Ludlum’s Bourne novels, and works by many other famous lights. Special treats lie in essays on Anglo-Saxon prose, Graham Greene, Ernest Hemingwulf, and on the downslide in earnings of Henry James who on one new year’s eve late in life found himself with 26 books in print and a zero bank balance. Writing does turn on money, not just art. The novel enlivens its pages as well with artwork and dozens of entertaining photos.

Rogo, something of a pale criminal, makes a Faustian bargain with the planet’s publishing colossus, Alexander Buda Sugarman, who sucks up book companies as so many chilled fresh Oysters Rockefeller. Many readers will find in Sugarman rich Hungarian echoes of Orson Welles in full throat. Poor Sugarman! He’s a widower but pursued by the ghost of his late wife Ayn Rand, who spurs him into his stranglehold on world publishing. He believes he finds her reincarnated in Fyodor’s wife Nastasya Filipovna, though some may find Nastasya far from Ayn Rand and more like the tragic heroine of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

Much of the novel takes place in Manhattan’s Strand Book Store and its Rare Books Room and draws into its web many very, very lightly disguised figures that drown daily in this world-class kingdom of second-hand books. What’s more, the novel reveals and leads you into the Strand’s secret subbasement catacomb where the bones of thousands of penniless Manhattan writers lie at rest, watched over by a blind hunchback not too distant from Notre Dame’s Quasimodo.

Do not miss the scene in chapter four at The Time Café where Rogo sells his soul to Sugarman amid tables full of American authors familiar to all who have also sold their souls.

DOWNPOUR

DOWNPOUR, a sexually intense short novel, is set in the early sixties on Manhattan’s Lower East Side during an April in which it rains every day of the month and floods the city –a true event. As retold by a down-at-heels 35-year-old writer, the story takes place amid a sexual revolution in child-rearing. A young mother tries to raise her children guilt-free in a sexually frank home much in line with a revolutionary work in child-rearing from England called Summerhill, which in the sixties created a following by youthful parents in the States. Much larger spiritual issues lurk in the subtext.

Gypsy, the heroine, is a 23-year-old philosophy grad and pursuer of Jungian analytic psychology who has fled her husband in California and hides out with her two children on the Lower East Side. Along with her bright mind and the fresh joy of the love-making, the story’s great strength lies in description and mood-setting and—as its five chapters rise step by step off the earth—a gathering sense of being on track toward heartbreak on an Edenic scale. And so we have the massive downpour and flooded streets as backdrop to a spiritual drama.

HELEN’S ASS STRIKES HOMER BLIND! or THE GREAT MEMORY

Helen’s Ass Strikes Homer Blind! tells of the élan vital of genius as seen in two of Newlove’s late friends, both geniuses — poet Jack McManis and Dr. Nathaniel David Mttron Hirsch. It first follows with inspired verse Jack’s daunting recovery from alcoholism and celebrates sobriety’s fresh charge to his poetry. The second half lifts off into scientific and philosophic rapture as Dr. Hirsch reveals the propulsion of human genius through our genes, and the higher source of that propulsion.

As with Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, Helen’s Ass Strikes Homer Blind! offers a one-of-a-kind reading experience. Jack McManis, a genius of 200-plus IQ, falls into madness, and then undergoes recovery through the agencies of Dr. Hirsch and Alcoholics Anonymous.

Dr. Hirsch meanwhile has published five books about experimental studies in heredity. These bolster his credentials as a scientist while his Genius and Creative Intelligence surges toward the philosophic plane he later reveals in his unpublished three-volume masterwork Metabiology. Hirsch’s metaphysics of biology leaps with deep originality to heights that few scientists or philosophers have sought. He tells of the brotherhood of genius as a higher form of life embedded on and given wing by genetic protein. Aside from Lucille Hirsch, his wife, I alone have the outline for this work. Metabiology offers as well a visionary sense of time and chance and many like subjects dear to philosophy. As with other geniuses, Dr. Hirsch knew he’d be seen as a crackpot, which he took as a high honor, for only those with pate cracked wide can receive the supersensible.

Helen’s Ass Strikes Home Blind! weighs the great bonding of Jack and Dr. Hirsch. In large part, Jack and Dr. Hirsch speak for themselves. Below are two of Jack’s verses, the first written while an active alcoholic, the second in mid-recovery. Jack’s drunken verses coat the tongue; his sober verse gives the heart a brain.

THE DUSTY MILLER

the dusty miller will eat

the worn carpet flowers

in my furnished room.

WILLIAM MARTIN OF LOCK HAVEN

1905-1971

William Martin had the gift of hands

laid on the sick-in-soul to make the soul well.

One night he placed his hand on my head and I

came out into light as though just born from the womb

of that void’s interminable nothingness

I’d laid in forever, too terrified to turn or cry out.

I didn’t believe in the laying on of hands

and I’m not sure I believe now, but I remember

as if it is happening and maybe it is —

William Martin’s gift of hands and how he dissolved

an infinity of darkness with a touch of his hand.

COMING SOON FROM OTEGO PUBLISHING: The Donald Newlove Edition of the COLLECTED POEMS OF JACK McMANIS with Selected Letters and a Revised and Enlarged Symphony of Brain Damage Papers (Fall 2012)

TRUMPET RHAPSODIES & Other Pieces of Time

Inventions, revisions and riffs based on magazine articles about famous people, first published in the Sixties and Seventies, every word now improved in a self-portrait featuring real writers and artists, nearly all of them dead, showing the author’s recovery from the illness of youth and meant to be read from first page to last as an autobiographical novel. Featuring Robert Lowell, fantasy artist Frank Frazetta, Samuel Beckett, Andy Warhol, Joseph Campbell, Fred Bass and the Strand Book Store, Gordon Lish, Raymond Carver, Edgar Allan Baudelaire, Elizabeth Lowell, Lana Turner, Pablo Neruda, Tennessee Williams, Cynara Rosewine, Coleman Hawkins, Elwood Babbitt, Jack McManis, Nancy Newlove, Donald Newlove and the author’s bruised mother.

This is a kind of autobiography of my early days as a writer and of my search for a language that trumpeted my youth. All texts have been revamped with inventions and variations that rhapsodize beyond the original scores to sing with improved art. The story “Superman Meets Captain Fiction” was written for this book and has never before seen print. Nor has “Taps”, written sixty years ago, or the poem “Elegy for Bean” written with Jack McManis.. — DN

BEAUTIFUL SOUP & OTHER WORKS OF MEMORY

This book features four works of fiction. The short novel herein of Beautiful Soup, in some ways my ideal version of that story, brings this piece as close to perfection as I can make it. (This version also appears on Kindle in Perfection: A Guide to Finishing a Work and Abandoning It Forever, which has five variations on the story.) The short novel Between Lives novelizes my play of the same name and I greatly enjoyed perfecting it as a short novel. The play version appears in Pleasures of the Night. The novel and the play and feature my late friend the actor-restaurateur Patrick O’Neal and Sir John Gielgud on a Hindu plane bound for Nirvana. Greta Garbo plays Gandhavati, their lissome flight attendant for Final Purification Airlines. The stories “Taps” (1954) and “Mount Zion” (2008) were written more than fifty years apart. “Mount Zion” links with “Taps” and with my ongoing love for the Russian master Tolstoy and more than ever for his short novel The Death of Ivan Illych — indeed, I call myself Ivan Illych in “Mount Zion” It’s great fun getting in the ring with Tolstoy — he was forty-eight when he wrote his story and I eighty writing mine. He beats me flat in every way but metaphysics.

THE THREE-HEADED PET DOG

The Three-Headed Pet Dog offers often long poems about people—Greta Garbo, Matthew Brady, Whitman, Chekhov, Poe, Marilyn Monroe, God the Poet, Rilke on his death bed, Annie Proulx, Garrison Keillor, Deborah Digges and others—and then a handbag of spirited serenities and sexy stuff such as “Love on the Night Lawn” and Newlove sharing the shower with his wife and Cleopatra and Ava Gardner. It offers as well the author’s four translations (or performances) of German verse by Paul Celan and Rilke. The longest poem, an elegy for Deborah Digges, shows her spirit as her three-headed pet dog Cerberus leads her from childhood into the underworld of poetry, mortality, midlife griefs and suicide. It is a poem of subtle strength with memorable rewards as Digges’ life grows and the poem’s mythic energy builds.

This is Newlove’s lone book of poems, plucked from over fifty years of writing. Another memorable poem is the large opening poem “Monarch” about the lives of Monarch butterflies which gives the reader the wondrous sense of endless rebirth. Come fly with me, the poem beckons.

THE PAINTER GABRIEL

Reviews for the hardcover 1979 edition:

(Now available revised and illustrated on Kindle)

THE NY TIMES SUNDAY BOOK REVIEW— Nora Sayre (full page)

. . . In Donald Newlove’s extraordinary novel, men and women are New York’s creatures as much as they are one another’s, even as they huddle tribally in the East Village, in the kind of dormitory-living that deepens mutual dependence . . . Mr. Newlove has a magnificent ear for every scale of language, from conviction to confusion, and he’s also deft with paradox. There’s a girl Scientologist (“I can’t lie to myself if I’m using a lie detector, can I?”); a truly white Negro who vows that he’s black and is hooked on Confessionalism; a Pole with a Hungarian name whose inflammable apartment is stuffed wall to wall with old issues of this newspaper and the News, which—unaware of microfilm—he’s devotedly cross-indexing and means to ship to the University of Warsaw Library. . . and Rosalie, who’s decoding Robert Browning—not only because he’s God, but because his poems reveal plots to murder Elizabeth Barrett Browning: “He couldn’t stand her, she was sick all the time.”

. . . Gabriel is a transcendental painter who gives the others a contact high. Wanting to see angels and to be one, he struggles with his own God-bothering: a brand of Whitmanesque blue-doming, lashed with some rather reluctant Christianity. For Gabriel, madness and divinity are the compost for art, so he risks losing his head for a “reintegration of psychosis.” Meanwhile, as a moderate sado-masochist, he yields his “thirst for chastity” to an occasional binge; to him, the women concerned seem like snakes or whores. Still, perhaps sex ”is as close as we get to God, this side of Bellevue.”

. . . Released after landing in Bellevue, he lives affectionately but warily with Rosalie, who is temporarily switched off Browning and onto Mobilization for Youth. Although she’s a profound schizophrenic, Gabriel is hopeful that they “can get well together.” His spiritual thoughts have dwindled but he misses his delusions. Love means “regaining your lost possessions, everything that you left behind in paradise.”

This constantly comic and (very) painful novel grows and acts upon you—in the best sense, it’s demanding. . . and if you live in Manhattan anything short of raving hardly sounds eccentric. . . It’s immensely moving and Newlove’s illustrations of far-flung religious impulses are just as absorbing and disturbing as they ought to be.

TIME Magazine – Robert Hughes (author of Goya)

Nether sections of Avenue B provide the Boschian landscape of hell. All of these horrors, lit by the glare of burning cars and the flash of pot or amphetamine, are the backdrop of one of the best fictional studies of madness, descent and purification that any American has written . . .Donald Newlove clearly set out to write a first novel about demoniac society. He has combined a morality play and grimoire , or devil’s hornbook, in which every creature is experienced with hilarious and dreadful concreteness.

. . . Gabriel is a prey to tumescent, Blakean mysticism, and an example of the outsider used as a corrective lens through which human absurdities may be studied. In the country of the loon the creative loon is king . . . amid clusters of amiable freaks, all of whom, like him, define a precarious balance by opposing their craziness to the paranoia of the outside city. . . Many of Newlove’s human inventions swell like bullfrogs from the sheer pressure of his linguistic vitality. . . Beside Gabriel the Best heroes of heroes of ‘50s fiction look not merely anemic but ignorant. Gabriel, simply, is romanticism cubed: “Scrape your brain bare, like a battery electrode, expose your nerves like a bush of copper. Get ready to sing or die. Or maybe both! And all this out here, these roofs and smokestacks, will turn into light—and you’ll see right through them—because they’ll no longer be necessary to support the illusion of our lives.” . . . Newlove’s muddy, inflamed picaresque novel is a remarkable performance.

LOS ANGELES FREE PRESS – Michael Perkins

Magnificent Madness on City Streets . . . It’s all real, folks, and presented with the “Vermeer-like clarity” Newlove says was his objective—an aspect of the book which might be missed, the language is so rich, the word-play so fine, and religion, mysticism, madness and revelation so prominent in the speech of its characters . . . a sometimes difficult, always demanding, extraordinary work of art, apocalyptic in subject and masterly in execution, as if Vermeer had undertaken to paint the hideous figures of Bosch.

. .. all the cruelties of the city are magnified in a Bosch hellscape, figures whose conversations dwell on heaven at almost every point, like angels dancing above the flames engulfing the monster city. Their talk . . . keeps the toes just above the fire but they end up in Bellevue, that fortress of death and madness which serves the Lower East Side. The painter Gabriel, who in the beginning is painting a canvas of the city burning, a vision which came to him in an intensity of mystical feeling, wants the angel’s charge.; and finally attains it in the eyes of a loved one gone mad. Donald Newlove has taken our mutually shared lower East Side and transformed it into a field where good and evil, devils and angels dwell, and he does it magnificently. - https://otegopublishing.wordpress.com/donald-newlove/essential-newlove/

Time magazine called his 1978 debut novel “one of the best fictional studies of madness, descent, and purification that any American has written since Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” The New York Times hailed his second novel as “one of the most desperately funny books we’ve been given in a long time.”

Yet the name of New York author Donald Newlove, now 91, has been all but obliterated from the late 20th-century American literary landscape. That’s all about to change, hopes independent publisher Rick Schober, owner of the one-man Arlington operation Tough Poets Press.

Last January, Schober published the first-ever new edition of Newlove’s Sweet Adversity, a sweeping 600-page semiautobiographical novel about alcoholic Siamese twin wannabe jazz musicians. Originally published as two separate novels — Leo & Theodore (1970) and The Drunks (1972) — Newlove edited them into a single volume, explaining in his introduction to the original edition that “the story loses scope and focus when halved into two books.”

Considering how well the original novels were received when they were first published, it’s surprising that both this book and its author fell off the literary radar.

Dramatic AA meetings

Lis Harris, writing in the New Yorker, called Sweet Adversity “a dazzling highwire act ... the sheer inventiveness and strength of his writing turn risk into triumph, drunken monologues into subtle satire, AA meetings into riveting dramas, and what in another writer might be bathos into brilliant comedy ... probably the most clear-eyed and moving—and certainly one of the most honest—books ever written about alcoholics.”

Newlove recounted his own alcoholism, along with that of other prominent American authors, in his memoir Those Drinking Days: Myself and Other Writers (1981). "Intoxication does mist and spiral in these pages,” wrote James Wolcott in his Esquire review, “but it’s the intoxication of language … writing in all its peacock splendor, writing that crackles and sings.”

Subsequent works by Newlove failed to find an audience and, eventually, even a publisher.

Shortly after the release of the Tough Poets Press edition of Sweet Adversity, Newlove sent Schober the manuscript for his unpublished 1998 novel, The Wolf Who Swallowed the Sun. Subtitled “A Jungian Fable of Family and Finance Across the Twentieth Century,” the novel is a sweeping saga of one family’s greed, extortion, and double-crossing as they strive to acquire a controlling interest in the world’s wealth.

It is also the story of Billy Baxter, heir to this massive fortune who, with the help of a married couple of Chinese-Swiss Jungian psychologists (one of whom he has fallen in love with), seeks atonement for his family’s sins. As an added twist that only a first-rate storyteller like Newlove could credibly pull off, Baxter also happens to be descendant from an ancient clan of humanoid wolves on the brink of extinction.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.