Jack Black, You Can’t Win: Complete and Unabridged, Sublime Books, 2016. [1926.]

borrow it here

My background is crowded with robberies, burglaries, and thefts too numerous to recall. All manner of crimes against property. Arrests, trials, acquittals, convictions, escapes. Penitentiaries! I see in the background four of them. County jails, workhouses, city prisons, Mounted Police barracks, dungeons, solitary confinement, bread and water, hanging up, brutal floggings, and the murderous straitjacket. I see hop joints, wine dumps, thieves' resorts, and beggars' hangouts. Crime followed by swift retribution in one form or another. I had very few glasses of wine as I traveled this route. I rarely saw a woman smile and seldom heard a song. In those twenty-five years I took all these things, and I am going to write about them. And I am going to write about them as I took them - with a smile.

The favorite book of William Burroughs. A journey into the hobo underworld, freight hopping around the still Wild West, becoming a highwayman and member of the yegg (criminal) brotherhood, getting hooked on opium, doing stints in jail or escaping, often with the assistance of crooked cops or judges. Our lost history revived.. With an introduction by Burroughs.

ANY AUTOBIOGRAPHY DEDICATED to the man who picked buckshot out of the authors back under a bridge at Baraboo, Wis., and to another fellow who sawed the author out of the San Francisco County Jail must be a hell of a read. Legendary beat writer William Burroughs thought so, as have hundreds of other readers who have managed to get their hands on Jack Black’s elusive You Can’t Win, a turn-of-the-century hobo/burglar memoir first published in 1926. Now reissued by AK Press, this printing will be welcomed by all those ready to live the outlaw life, if only vicariously.

Black’s matter-of-fact treatment of the hobo life resonates with honesty. We watch Black first-hand as he deals with women of so-called negotiable virtue; as he visits the opium dens or hop joints scattered about San Francisco’s Chinatown; and as he relates to the safecracker hipsters of the era known as yeggs. We see Black in all of his glory: jumping rails, witnessing shootings, robbing banks, and ironically obeying the law – that is, the law of the Johnson’s, a code of ethics among burglars and thieves that rivals anything respectable society has managed to promote.

With Black we roam the countryside, meeting characters like the Sanctimonious Kid, whose name speaks for itself; foot-and-a-half George, whose leg injury was the result of a safe blowup gone awry in Butte, Mont.; and Salt Chunk Mary in Pocatello, Idaho, whose principal business was selling wine, women, and song (not to mention fencing stolen jewelry) to the railroad men and gamblers who passed through town.

This book offers not only the boastful burglar, telling of his fantastic heists, but the burglar who can, now that time has passed, look back on the unsuccessful exploits with humor. We have the time Black and his comrades in crime blew open the door on a huge safe only to have it fall on its face – too heavy for Black to get its contents. We have the story about Black and his partners purposefully being arrested for vagrancy, breaking out of jail to commit a successful burglary, only to break back in for the perfect alibi. Over and over again the book delivers. It is engaging, with nothing of the sensational for its own sake.

The first publication of this book in 1926 went through five printings in less than one year. The 1988 reissue by AMOK press included an introduction by William Burroughs, of Naked Lunch fame, who acknowledged the influence this book had on him. The new edition, ushered in by Bruno Ruhland and AK Press, includes the Burroughs preface as well as a nearly 40-page afterword by New York City 1960s literary underground figure Michael Disend (whose own novel, Stomping the Goyim, was praised by Burroughs as “brilliant”). Disend’s afterword alone, written in a powerful and irreverent style, is worth the price of the book. He rightfully places You Can’t Win in the turn-of-the-century prison reform movement that was sweeping the country at the time. Disend politicizes Jack Black by taking the book beyond the romanticism of the on-the-road genre and into the realm of politics and an indictment of the modern prison industrial complex. Sure, readers will love the book because of the great story-telling, but Disend’s afterword helps a new generation see the message of redemption in this post-Three Strikes, post-Proposition 21, prison state America is turning into.

Black’s memoir undermines the notion that violence and inhumanity will somehow reform him. Black survives a chain gang in Denver, flogging in Canada, being straitjacketed in Folsom prison, and three weeks in the infamous cooler of Utah’s state prison, where he lives in darkness surrounded by steel walls, is giving no bedding, and must survive on a single slice of bread a day. He also endures the psychological terror of witnessing the hanging of a fellow prisoner in the San Francisco jail from his own cell a few feet away. But it isn’t until his brutal beating and choking by a notoriously cruel sheriff in Seattle named John Corbett that he condemns, somewhat prophetically, our modern approach to reforming criminals: “If people can be corrected by cruelty I would have left that cell a saint.” And he didn’t, of course, because we cannot beat justice into a man no matter how hard we try. Nor can we employ cruelty to obtain or guarantee safety because the societal ills that encourage criminality are not diminished in the least by such acts of retribution.

What is beautiful about this book is the realization that Jack Black changes because other men believed in him and took the chance that he wouldn’t betray their trust. He changed because he saw things as a result of the life he led, not in spite of it. Michael Disend’s afterword is filled with historical research that tells of what became of Black after the publication of You Can’t Win. Without giving away the details, let’s just say there were many surprises, as many as are contained in this engaging memoir.The publication of this new edition of You Can’t Win coincided, ironically enough, with the final verdict to be recorded in the San Francisco’s criminal courts in the last millennium. Just as the book reached the bookstores in San Francisco the last week of 1999, Frank Grano, who was facing life in prison under the Three Strikes law for the nonviolent charge of receiving stolen property, was found not guilty by a jury at the Hall of Justice. He had chosen to represent himself against an experienced prosecutor and all the odds. Jack Black, who himself faced life in prison in a San Francisco courtroom at the turn of the last century, would have approved. - Matt Gonzalez

https://themattgonzalezreader.com/2009/06/15/jack-black-rides-the-rails-again/

Jack Black’s autobiography, originally published in 1926, was apparently William Burroughs’ favourite book – Denton Welch was his favourite writer, by the way, so there is perhaps a little bit of a contradiction here – and he provides an appreciative foreword to the AK Press edition of You Can’t Win. On even a first reading, it is easy to see why Burroughs would admire the book: Black was an outsider, a criminal and an opium addict, and he presents a compelling (and cynical) insider’s view of the justice system of the time. And for this last alone, the book is a valuable document: a criminal outsider of intelligence pretty much tells it like it was. More crucially though, there is often a sense, as you read, that Black’s is a voice we weren’t meant to hear – at least not in this form. For Jack Black isn’t a monster; he comes across as being (at the end, at any rate) a wise and compassionate man.

A large part of the charm of You Can’t Win is that it reads like the hard-boiled American fiction of the ‘20s; like Hammett or one of the other Black Mask boys. Chapter 20, in particular, is a superbly told story: an account of a payroll robbery and its fallout that pushes all the right buttons. Like many of Black’s adventures (or at least like those recounted here), it does not end well. Downbeat doesn’t do it justice.

Throughout, the writing has great immediacy and the same sort of authenticity with regard to the criminal life as the first few chapters of Edward Bunker’s later No Beast So Fierce. This is so whether Black is describing dodging railroad bulls and jumping on boxcars, getting picked up for vagrancy or winding up in a jailhouse where “a coloured woman was singing a mournful dirge about ‘That Bad Stackalee’”. Many scenes bring to mind images from old American films: a lost world, but one we’ve seen or seen imagined.

We follow Black’s life from the 1890s to about the mid-1920s. He is attracted to crime as a kid of 14, after reading tales of Jesse James and others, and at first it is a life of adventure and excitement. Later, as he becomes a “yegg” (a travelling thief), he comes to see crime as a game or sport: there are codes and rules, smart plays and foolish moves, allies and opponents. At the end, after opium addiction (“opium, the Judas of drugs, that kisses and betrays, had a good grip on me,” Jack writes at one point) and time spent in Folsom, Alcatraz, San Quentin and other prisons, he arrives at the pessimism of his title: you can’t win. Crime doesn’t pay. Still, he went to hell in his own way, which is the best any of us can hope for.

There are some extras here, to add to the Burroughs foreword. An afterword by Bruno Ruhland gives some further background of Jack Black’s life; and Ruhland’s account of the social reformer Fremont Older is interesting too. There is also an article by Black about prison reform: “What’s Wrong with the Right People?”.

To sum up: this is a memorable book and was an influential one too, for the Beats especially (“on the road” is a phrase that recurs throughout; Kerouac seems to have palmed it from here). It is that rare thing: a cult book that lives up to its reputation. Its take-home message: the world is a tool for self-discovery; not at all bad for an autobiography. - Paul Kane

http://www.compulsivereader.com/2007/11/06/a-review-of-you-cant-win-by-jack-black/

Current Exhibit: You Can’t Win: Jack Black’s America, Curated by Randy Kennedy

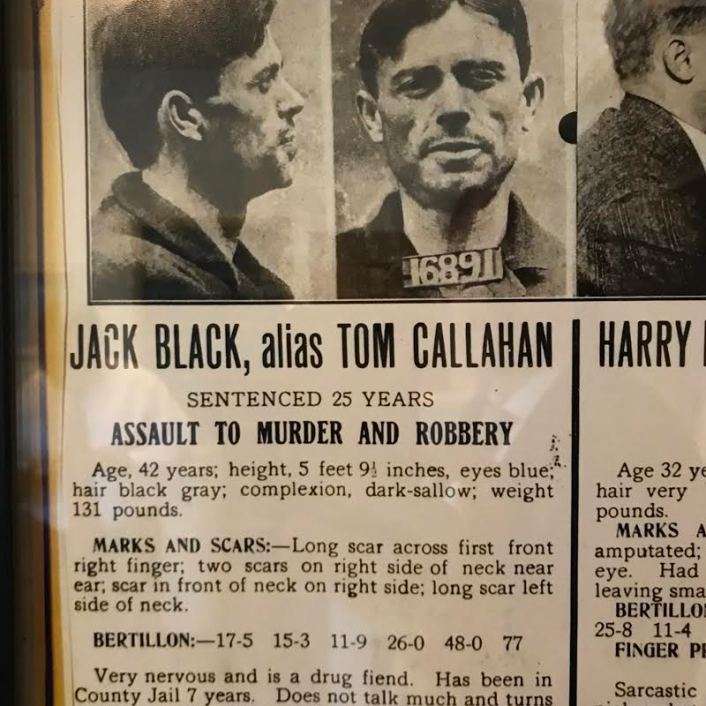

In 1926, Jack Black’s career took another unlikely turn. The former vagrant, burglar, addict, convict, escapee, and, more recently, librarian of the San Francisco Call could now boast that he was a best-selling author to boot. Black had dictated his memoir – a criminal CV covering some thirty years’ experience across the pre-Volstead West – to none other than Rose Wilder Lane; under the sage editorship of Fremont Older, the feature had been serialised in the Call as a cautionary tale – a set of variations on the theme of ‘crime doesn’t pay’ – and it had proven so popular, moreover, that MacMillan decided to publish. You Can’t Win underwent five further reprintings, and the ‘one-man San Francisco reign of terror’ became a New York lecturer, Harper’s essayist, one-time dramatist, and salaried screenwriter for MGM. Black had won – or so it seemed until his sudden disappearance in 1932. ‘Fremont,’ wrote Older’s wife, reckoned Black ‘did what he always said any down-and-outer should do, “fill his pockets with rocks and take a header into the bay.”’

Today, Black’s reputation is chiefly floated by William S. Burroughs’ old habit of naming You Can’t Win his favourite book. Prefacing the AK Press edition of 1988, Burroughs explained the book’s attractions. It introduced him to a ‘code of conduct’ which ‘made more sense’ than the ‘arbitrary, hypocritical rules … taken for granted as being “right”’: crime might not pay, but the ‘straight’ life, for Burroughs, was itself so crooked, and its odds stacked so heavily against the vast majority of its players, that even on the ‘right’ side of the law you could never really win. Hence, Black’s book also stirred in Burroughs ‘a deep nostalgia for a way of life that is gone forever’. And for this, Burroughs can’t really be blamed: when Prohibition came into force at midnight on 17 January 1920, the new outfits made the likes of Black look like the tinkerers of yore. Little wonder that Burroughs made constant reference to You Can’t Win within his own books, even copying entire sections into The Place of Dead Roads.

Black, however, happens to have pre-empted Burroughs’ admiration in an essay of 1930. ‘A Burglar looks at Laws and Codes’ has this to say about ‘hypocritical rules’:

The law… has become complicated, perverted, prostituted. Special legislation has made of it a cloak for all kinds of high-roguery. Specialized enforcement that penalizes one man and lets another brush by for a like offense has brought it into disrepute…If the rules governing baseball were as complicated as the income tax law, the world’s series would rival “Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce”. Laws make lawyers and lawyers make laws and this makes a sinister circle that grows larger and larger.For Black, then, the law is both inefficient and indecipherable, not just corrupt but fundamentally criminal. The actual criminal’s ‘code of conduct’, meanwhile, enforces behaviours far closer to what we might think of as being lawful:

The criminal’s code is based upon the same fundamentals as the social code: protection of life and property…It pays its debts and its grudges on the minute. The crook, like the business man, strengthens his position and credit if he meets his bills and discharges his obligations promptly.But if the ‘law’ and the ‘code’ are not wholly distinct, nor are they compatible:

It’s in the book that the crook pays his room rent and his board…to fail to pay the board bill is an admission that he is a “slow connecter”; he can’t make the grade. In other words, he’s a failure in his profession; not a thief but a dead-beat. Sooner or later he winds up where he belongs, stealing milk bottles and doormats, serving short sentences in small jails, despised by honest people and shunned by “honest” thieves.

The crook has one yardstick for measuring the conduct of the upperworld, another for the underworld. If his attorney strips him of his loot, as frequently happens, he is supposed to whistle it off and take it out on the next citizen that he meets. The attorney belongs to the upperworld, and the crook’s obligation ends when he exposes him to his fellow crooks. But if a thief’s partner robs him of his end of the loot he must “regulate” him according to the code, or lose caste.Hence, ‘A Burglar looks at Laws and Codes’ urges its reader not to romanticise the pre-Volstead years, reminding us that the law – the ‘arbitrary, hypocritical rules’ so despised by Burroughs – was then operating in perfect tandem with the criminal world and its ‘code’:

The more strictly a criminal adheres to the underworld code the greater will be his handicap if, and when, he decides to mend his ways. This adherence makes him friends, and he is proud of it; but these very friends help to anchor him in that life

I’m not finding fault with these brave days of jungle music, synthetic liquor, and dimple-kneed maids, and anybody that thinks the world is going to the bowwows because of them ought to think back to San Francisco or any other big city of twenty years ago- when train conductors steered suckers against the bunko men; when coppers located “work” for burglars and stalled for them while they worked; when pickpockets paid the police so much a day for “exclusive privileges” and had to put a substitute “mob” in their district if they wanted to go out of town to a country fair for a week. Those were the days when there were saloons by the thousand; when the saloonkeeper ordered the police to pinch the Salvation Army for disturbing his peace by singing hymns in the street; when there were race tracks, gambling unrestricted, crooked prize fights; when there were cribs by the mile and hop joints by the score.But if Burroughs’ ‘nostalgia’ was misplaced, why should anyone care about Black’s book at all?

II

A good answer has been yielded – albeit indirectly – by the current exhibition at the Fortnight Institute – You Can’t Win: Jack Black’s America. As Randy Kennedy, the exhibition’s curator, writes in the press release:Black’s America is not historical. We live in it today, in ways that he foresaw and ways he could not have imagined, or would not have wanted to. What Faulkner said of the South applies equally to every part of the country, especially in the Trump era: “The past is never dead; it’s not even past.” Black’s alienation and evocation of life on the lam trace two interrelated kinds of disappearance: chosen and enforced. Between them lies a third: that of people born into American society already disappeared, socially and economically, because of race, gender and other fundamental aspects of their being.For Kennedy, Black’s America – in which even the ‘straight’ population found itself disaffected and disenfranchised en masse – is uncannily like today’s. And the Fortnight exhibition is largely devoted to demonstrating that this is the case. Kennedy continues:

The works in the show could be regarded as unindicted – or perhaps indicted – co-conspirators of Black’s deep anomie and solidarity with the subjugated. Beverly Buchanan’s Miz Hurston’s Neighborhood Series – Church, from 2008, locates her beloved shack sculptures in a specific milieu, the Florida of novelist Zora Neale Hurston, where Hurston’s life ended in obscurity in a welfare home, her body buried in an unmarked grave. The self-taught artist Pearl Blauvelt (1893-1987), made her phantasmal drawings—discovered accidentally, years after her death—in a house in northeastern Pennsylvania where she had lived alone without electricity or plumbing; neighbors called her the village witch. Martin Wong’s prison paintings, often depicting his friend, the playwright and activist Miguel Piñero, shimmer with tenderness and carnality for the cellmate. Selections from Luc Sante’s folk postcard collection double as the incriminating pictures of a feral young nation that Black himself never had time to take, between jobs. The 1991 painting by Burroughs and poet John Giorno encompasses all-American violence as if it were made yesterday…You Can’t Win, then, continues to resonate because, for the most part, you still can’t win: the ‘straight’ life remains a fixed game, and the house still doesn’t ever lose.

But some have felt that Black’s book does more than simply foreshadow the inequalities of our own era. The 2013 edition of You Can’t Win from Feral House carries on its cover the following testimony from Nick Tosches:

Jack Black’s book has too often and for too long been looked on, more by reputation than by reading, as a ‘cult classic,’ implying that it belongs to the fringes of literature. Nothing could be more untrue. It deserves a much vaster, if not universal, audience. More than – rare enough – a damned good book, it is a book of timeless, illuminating truth that offers the antidote to the poisonous lies, from the fool platitudes of faith to the rot about the inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, that have made suckers and losers of us all. This book is one of a kind.Here, Tosches rephrases the standard arguments for canonicity. To claim that a book might deserve a universal audience is to suggest that everyone should or ought to read it. The suggestion is qualified by two more: first, that You Can’t Win possesses a qualitative superiority which distinguishes it from the majority of published works – that it is ‘rare enough – a damned good book’; second, that You Can’t Win is not some artefact, not merely an evocation of a particular era, but a work that transcends the circumstances of its production and speaks ‘timeless, illuminating truths’. Heartening stuff, but what would Black have made of these endorsements?

From the very outset of You Can’t Win, Black is acutely sensitive to distinctions of quality. Describing his introduction to books and reading, he relates the following story:

One day I found a dime novel and devoured it. After that I was always on the lookout for dime novels… I read them all. “Old Sleuth,” “Cap Collier,” “Frank Reade,” “Kit Carson.” Father saw me with them, but never bothered me. One day he brought me one of Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. I read it and was cured of the five- and ten-cent novels.Almost as soon as he enters the world of literature, then, he learns to discern high from low, legitimate from suspect, art from pulp. And once he has discovered the former, the latter becomes intolerable to him. Perhaps unsurprisingly, You Can’t Win goes on to reproduce, albeit in miniature, that thing beloved by every hard-line advocate of the canon – a list of Great Works:

The widow gave me a trunkful of books she had taken for a board bill. Among them I found a battered old volume of Dumas The Count of Monte Cristo, on which I put in many nights. This sharpened my appetite for reading, and I went around second hand bookstores and got hold of the D’Artagnan tales and devoured them. Then Les Miserables, and onto the Master, Dickens.Did Black wish to be ranked among this high company? Should we read his autobiography as Literature-with-a-capital-L?

We would be fools to try. The laws of canonicity – the regulations by which the cultural authorities determine whether a text is deemed a legitimate Classic, a work fit for universal study – are as complex, as baffling, and, for many, as politically corrupt as the actual law seemed to Black. One could not, in the scope of this or any piece, hope to lay down their complete sections and subsections, nor pass judgement on whether Black’s book adheres to them. And even if we could, it would be hard to imagine even a reformed crook like Black deliberately observing any kind of law when setting down with Lane the record of his criminal career; if Black’s book ever fulfils the laws of canonicity, it does so, surely, by accident. This is not to suggest that You Can’t Win should be discarded along with the dime novels of Black’s youth: Black’s most important difference from Cooper, Hugo, Dumas, and Dickens is not one of quality but one of kind. And to attempt to measure You Can’t Win against their ‘yardstick’ would be fruitless, therefore, for it is Black’s very refusal to stand within its scope which lends his book its strange affect.

And this is another thing which Black’s book has in common with the other works collected at the Fortnight Institute: all come from the margins of their respective fields, and draw their power from the fact that they cannot be measured against the officially-sanctioned criteria of canonicity.

III

The ten photo postcards from the personal collection of Luc Sante are no exception. As Sante writes in Folk Photography: The American Real Photo Postcard 1905-1930:The photo postcard is a vast, teeming, borderless body of work that might as well have a single, hydra-headed author, a sort of Homer of the small towns and the prairies. Self-taught and happily ignorant of the history of the medium, this author was free of the sort of second-guessing that cripples artists. He or she was out to do a job, to please a public, to turn a dollar, but also to record things faithfully, to hold up a mirror to that bit of the world shared with the clientele, maybe to make the familiar strange, simply by noticing things. Freedom from the historical burden made for an aesthetic that prized above all finding the distance between two points. That is, the pictures are most often blunt and head-on, and in fact are best when they are blunt and head on.I have collected similar cards, with varying degrees of seriousness, since childhood. What draws me to this arcane pursuit is hard to define [for if I could perfectly articulate it, presumably, I wouldn’t be drawn to it anymore]. On the one hand, photo postcards seem to eschew, either by chance or design, the established ‘laws’ of the photographer’s art. At the same time, they clearly adhere to what Black might have called a ‘code’: not only do they fall into clear ‘types’, genres unique to the medium [train-crashes and shipwrecks are particularly well represented in my collection], they also seem to embody a common aesthetic, a shared sensibility by which it is possible, moreover, for a collector to assess [in retrospect, of course] a particular card’s success. And the best I can do to explain that sensibility is this: a card is significant, I think, not simply when its subject reminds us of the present day, but when it records something which has been overlooked in the grand-narratives of History – when it documents some minutia which hasn’t been assimilated within the authorized accounts. The presence of Sante’s cards [all of which are exceptional] within the Fortnight exhibition forces us to ask further questions of You Can’t Win. Does it too partake in a shared sensibility? Does it adhere, in Black’s words, to some ‘code’? If it won’t be measured against Cooper, Hugo, Dumas, and Dickens, how does it fare against the other hobo biographies of the inter-war period?

You Can’t Win might seem unique among its companions-on-the-road. Jim Tully’s Beggars of Life was published only two years before You Can’t Win, but the life it describes is crucially different from Black’s. Tully was born near St Mary’s Ohio in 1871 – some twenty years after Black; the ‘way of life’ whose loss was mourned by Burroughs had all but vanished by the time Tully arrived on the scene. Tully’s wanderings, moreover, were largely restricted to areas in and around Cincinatti. And he was, crucially, no criminal, but a migrant worker: a roadkid, factory slave, circus hanger-on, stakedriver, ditchdigger, chain maker, tree surgeon, boxer, and, eventually, a Hollywood journalist and secretary to Charlie Chaplin. Dr Reitman’s Sister of the Road, meanwhile, was published a whole decade after Black’s book and is not, strictly speaking, a biography at all: Boxcar Bertha, the book’s narrator – though she is, like Reitman, both a gynaecologist and an anarchist agitator – is ultimately a fictional creation.

Nevertheless, the three texts are united by two things. First, each is told in the first person and rendered in radically unsentimental prose [Jim Tully has even been credited with inventing the ‘hardboiled’ style popularised by Dashiell Hammet]; second, each of their respective narrators is a vagrant – a figure on the bottom of the social ladder, with little or no hope of moving up it, and whose want of social mobility is only matched by an excess of physical mobility. The vagrant, then, is probably best viewed as the opposite of flaneur – the urban wander of Nineteenth Century Paris who is able, as Baudelaire originally put it ‘To be away from home and yet to feel at home anywhere, to be at the very centre of the world, and yet to be unseen of the world’; the vagrant, by contrast, is homeless wherever he find himself, and always consigned to the position of outsider. And it is due this position that Black’s stories of domestic burglary are particularly fascinating: they are accounts of stealing into people’s homes, of breaking into their inner sancta, narrated by an unsentimental outsider for whom the very concept of ‘home’ has long become alien. Not only are they deeply disorienting, therefore, they also form precisely the kind of detail which, by definition, doesn’t make its way into the authorised accounts of the pre-Volstead West.

There is little doubt, then, that You Can’t Win is, in Tosches’ phrase, ‘a damned good book’; more specifically, it is a ‘damned good’ example of the vagrant biography – one whose success, moreover, is attributable to the fact that it places the subjective experience of the outcast squarely at the centre, rather than at the margins, of its narrative. And it is this same sensibility which ultimately unites the works in the Fortnight exhibition: all have the feeling of being, in some way, ‘outside-in’. - Oscar Mardell

www.3ammagazine.com/3am/you-still-cant-win/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.