Lucebert [Lubertus Jacobus Swaanswijk], The Collected Poems: Volume 1, Trans. by Diane Butterman, Bilingual ed., Green Integer, 2010.

The Dutch poet and painter Lucebert (pseudonym for Lubertus Jacobus Swaanswijk) was born in Amsterdam in 1924, the city where he was to live for nearly thirty years. After a bohemian period in his twenties -- when he made several trips to France, especially to Paris -- he finally settled in the North Holland coastal town of Bergen where, until the time of his death in 1994, he lived with his wife and family for more than forty years. In his latter years he divided his time between the house and studio in Bergen and the family holiday home in Spain. When Lucebert burst onto the literary scene in the early fifties he soon became a sensation, largely because of the experimental and enigmatic quality of his verse. Predictably, such an original poet was instantly embraced by the literary avant-garde of the day as a welcome, fresh and exciting new phenomenon in sleepy post-war Europe, but he was simultaneously eyed with great suspicion and unease by the Dutch establishment whose very foundations he rocked.

An energetic and prolific writer and artist, he wrote and published almost 700 poems and generated literally thousands of paintings and drawings in his productive working lifetime which was to span some fifty years. Lucebert’s early impact soon made him an established and acclaimed poet throughout the Dutch-speaking world. The three collections contained in this first volume date from 1951 and 1952 and the accompanying uncollected poems are from the 1949 to 1952 period. High time one might therefore say, some sixty years on, for the poetic works of this vibrant and important voice within the Dutch literary canon to appear in four consecutive volumes in the English language.

This first volume contains an authoritative and extremely interesting introduction written by the Dutch academic and Lucebert expert, Anja de Feijter, who is currently professor of Modern Dutch Literature at the Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands. It is the first volume of the complete works of this leading twentieth-century Dutch literary figure to be published in translation by Green Integer.

It goes without saying that the poems of Lucebert, one of the best known and most influential poets in the Netherlands of the last century, are not entirely unknown beyond our borders.

Already his work has been translated into more than twenty languages and at various times in the past splendid anthologies have appeared in countries such as Spain, Germany and France. However, the plans that Douglas Messerli – an American publisher at Green Integer Books in Los Angeles – now has, amount to something completely unique in international terms: he is producing a bilingual version, in several parts, of the entire works.

Some years ago he published an anthology entitled Living Space: Poems of the Dutch Fiftiers. It was the Emperor of the Fiftiers that stole Messerli’s heart, though, and so he went in search of a translator to help him realize his publishing dream. It was through the Dutch Foundation for Literature that he finally came into contact with Diane Butterman who had, for a long time, been fascinated by the poetry of Lucebert. She it is who has translated The Collected Poems of Lucebert, Volume 1. It contains the one hundred and twenty-six poems written by Lucebert between 1949 and 1952 in both their original Dutch form and English. The translations are preceded by an introduction written by Anja de Feijter, Professor of Modern Dutch Literature at Radboud University in Nijmegen.

What motivated you, the translator, to spend a number of years working specifically on the poetry of Lucebert?

Butterman: ‘His experimental verse is magnificent, very layered and complex. That is what makes it such a huge translation challenge. For me the poetry embraces both the beauty and the innovative power of language. In the translations it is not my voice that comes through but his and that is something rather stunning. When I reread the work I perpetually discover new layers of meaning: that can only be a testimony to the sheer vitality of his verse.’

Are you meanwhile busy working on the second volume?

‘The second volume is more or less completed. I just have to finish compiling the notes so it should come out in the course of 2014. At the same time, I am also working on the poems for volume three: there will be four volumes in all, each of which will be between six and seven hundred pages long.’

Do you have an idea how the work of Lucebert will come across for the American reading public?

‘I am convinced that American readers will be open to the poetry of Lucebert. There will be recognition because of the considerable parallels with their own literary history. Within the broader context of world literature it falls into the sub-genre known as late modernism. In the Netherlands anyone who thinks of Lucebert automatically thinks of the Fiftiers and the avant-garde movement Cobra but in the English-speaking world there were similar movements such as the Beat Generation Poets in America.’

The second, third and fourth volumes will appear consecutively in the next few years. The first volume can be purchased from the more established bookshops or ordered via the Green Integer webshop. - Thomas Möhlmann

http://www.letterenfonds.nl/en/entry/339/luceberts-collected-poems

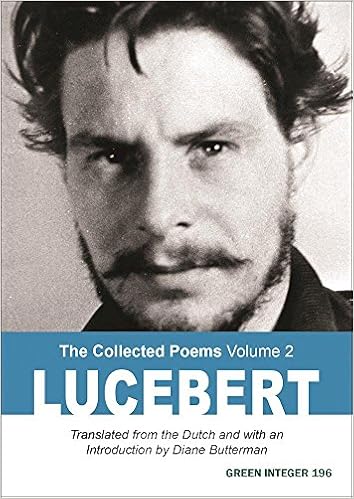

Lucebert, The Collected Poems: Volume 2, The Collected Poems: Volume 1, Trans. by Diane Butterman, Bilingual ed., Green Integer, 2017.

Lucebert (pseudonym of Lubertus Jacobus Swaanswijk, 1924-1994) was born in Amsterdam, the city where he lived for almost 30 years. In the 1950s he settled in Bergen (North Holland) with his wife and family, the place where he was to live for some 40 years, until the time of his death.

It was the experimental and enigmatic quality of his verse that was to make Lucebert a sensation in the early ’50s. He was instantly embraced by the literary avant-garde of the day but eyed with great suspicion and unease by the Dutch establishment whose very foundations he rocked.

An energetic and prolific writer and artist, he saw the publication of 15 collections of poetry. After his death, all these collections, together with numerous uncollected and posthumous poems, appeared in one large volume (Bezige Bij, 2002).

His legacy includes thousands of paintings and drawings. Today, 60 years after his literary debut, he is universally acknowledged as an established and acclaimed poet throughout the Dutch-speaking world.

The four collections in this second volume were published between 1952 and 1959. The accompanying uncollected poems date from the 1953 to 1963 period.

No other twentieth-century Dutch poet made an entrance quite like Lubertus Swaanswijk, alias Lucebert (1924-1994). He seemed to come out of nowhere. Although the picture turns out in retrospect to be slightly romanticised, Lucebert led a wandering existence in the years after World War II. He began to gain a reputation as an artist and painter among his immediate circle; however his poetic talent remained hidden for a long time, even from his friends. The poets Gerrit Kouwenaar and Jan G. Elburg, who were in close contact with the experimental artists of the CoBrA movement and knew Lucebert as a visual artist, were dumbfounded when he recited some of his poems one evening.

With the ‘birth’ of Lucebert as a poet, Dutch poetry suddenly gained an incomparable voice. What’s more, Lucebert’s work had connections to traditions that were unknown or barely known in the Netherlands, such as mysticism, German Romanticism, Dada and other modernist trends. He brought a new élan to the type of experimental poetry that had had scarcely any following in the northern Netherlands since the pioneering work of the Belgian Paul van Ostaijen. With his poetry and performances, in which there was also an element of wanting to shock the middle class, Lucebert showed the way to a group of young poets named after the decade in which they began to make their mark: The Fiftiers (De Vijftigers). One happening, which culminated in a riot, saw Lucebert crowned emperor of the group (wearing fancy dress).

It is now twenty years since his death, and for many people in the Netherlands Lucebert still stands on the pedestal on which he, with his sense of irony, put himself. Poet, novelist and critic Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer writes: ‘Not everyone realises it yet, but in ten years’ time there’ll be no doubt left in anyone’s mind that, Vondel aside, Lucebert is the greatest Dutch poet of all time. I look on him as my teacher.’ Yet Lucebert often provoked disapproving reactions too. As early as 1953, two years after Lucebert’s debut in book form, writer Bertus Aafjes came to the rather hysterical conclusion that Lucebert’s work ushered the SS into Dutch poetry. In 2010, the poet Maria Barnas took the measure of the Lucebert anthology selected and introduced by Pfeijffer, and again was ultimately negative in her conclusion.

The key to this disapproval lies in the subtitle that literature professor Thomas Vaessens gave to De verstoorde Lezer (The Unsettled Reader), his book about Lucebert, namely Over de onbegrijpelijke poëzie van Lucebert (Lucebert’s Incomprehensible Poetry). Lucebert’s poems are particularly difficult for anyone who approaches them logically and rationally. Sound and rhythm are the basis for a language game that is as virtuosic as it is boundless, and that bursts with associative mental leaps and references to sources often largely hidden from or unknown to the reader. Literature professor Anja de Feijter, for example, has demonstrated the theory that, in his early work in particular, Lucebert was influenced by the Jewish mystical tradition of the Kabbalah, among other things. Lucebert’s method of working has also been convincingly compared with the way in which jazz musicians improvise.

The same De Feijter has written the foreword to the first part of Lucebert: The Collected Poems, the ambitious undertaking of translator Diane Butterman, who plans to render Lucebert’s entire body of work into English. Lucebert’s poetry is so complex that Butterman’s intention seems arrogant to anyone who has not read her translations. Butterman herself gives a detailed account of her choices, but in order to really assess the quality of her achievement, it is a good idea to consider a few examples of what makes Lucebert’s poetry difficult, and translating it even more difficult.

One tricky issue is Lucebert’s penchant for ambiguous words. Other languages seldom possess words with exactly the same meanings. The following poem illustrates this point:

haar lichaam heeft haar typograaf

spreek van wat niet spreken doet

van vlees je volmaakt gesloten geest

maar mijn ontwaakte vinger leest

het vers van je tepels venushaar je leest

spreek van wat niet spreken doet

van vlees je volmaakt gesloten geest

maar mijn ontwaakte vinger leest

het vers van je tepels venushaar je leest

leven is letterzetter zonder letterkast

zijn cursief is te genieten lust

en schoon is alles schuin

de liefde vernietigt de rechte druk

liefde ontheft van iedere druk

zijn cursief is te genieten lust

en schoon is alles schuin

de liefde vernietigt de rechte druk

liefde ontheft van iedere druk

de poëzie die lippen heeft van bloed

van mijn mond jouw mond leeft

zij spreken van wat niet spreken doet

van mijn mond jouw mond leeft

zij spreken van wat niet spreken doet

her body has her typographer

speak of what cannot be spoken of

of flesh your perfectly closed spirit

but my awakened finger reads the verse

of your nipples venus’ hair your waist

speak of what cannot be spoken of

of flesh your perfectly closed spirit

but my awakened finger reads the verse

of your nipples venus’ hair your waist

life is typesetter without printer’s draw

its italics is lust to be enjoyed

and beautiful is all that is oblique

love destroys the standard print

love frees from every imprint

its italics is lust to be enjoyed

and beautiful is all that is oblique

love destroys the standard print

love frees from every imprint

poetry that has lips of blood

that lives on my mouth your mouth

they speak of what cannot be spoken of

that lives on my mouth your mouth

they speak of what cannot be spoken of

Apart from the sound play of rhyme and alliteration, there is the insurmountable problem of the words ‘leest’ and ‘druk’, the double meanings of which cannot be preserved in English. ‘Je leest’ at the end of the fifth line is particularly problematic. It can be read as both ‘you read’ and ‘your waist’. Butterman chooses the second option; translating is a matter of accepting there will necessarily be some loss. In any case, Butterman’s translations succeed in safeguarding the vitality of Lucebert’s poems, despite the fact that much is lost (something Butterman readily admits to in her notes), for example that quality of Lucebert’s work that ‘builds poems from the swirling quasars of individual words’, as Pfeijffer puts it.

Lucebert is a poet in love with words who, time and again, allows himself to be led by the richness of sounds and the ambiguity of language. He is fond, for example, of using words that can be read as both verbs and nouns, such as ‘saw’ and ‘neck’. Because he uses no punctuation, there is often no single authoritative reading. Both meanings are intended, but the translator is forced to choose. What is commendable is that Butterman does so without reservation. However difficult this must have been, it is important that the reader who cannot speak Dutch is served up a good poem and not an integral rendering of all possible sounds, figures of speech and layers of meaning. And Lucebert’s poems are good in English too. The resulting clarity would perhaps be undesirable for the poet, but it is not unpleasant for the reader.

In such a comprehensive and ambitious project, some decisions are always going to be debatable, but Lucebert holds his own surprisingly well in English, and consequently the translator does too. - Mischa Andriessen Translated by Rebekah Wilson

First published in The Low Countries, 2014

http://www.literaturefromthelowcountries.eu/poet-love-words/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.