“When considering the canon of inventive, intelligent works of fantasy, it’s probably fair to say that if the Codex Seraphinianus by Luigi Serafini didn’t exist, it would be necessary to invent it. Imaginary worlds are as old as the human imagination itself and will be with us for as long as imagination lasts, despite their currently rather devalued reputation as staples of bad science fiction and fantasy. Conveyor-belt proliferation aside, ‘We all love a mysterious country,’ as Nebuchadnezzar the dandy reminds us in David Britton’s Lord Horror, the words being a quote from M John Harrison’s ‘Egnaro’, a story that is, in part, an examination of the condition and effect of imagined worlds (and in Harrison’s story the quote comes from Lucas, a character based on David Britton—how’s that for a circular reference?) Most invented worlds, however, serve only as the backdrop for a narrative, whatever mythologies or ersatz histories might be created to substantiate their existence. The Codex Seraphinianus is unique in placing its invented world centre stage and, even more uniquely, purporting to be a product of that world itself. Its creation seems the inevitable result of a trend of fantasy writing that delights in invention purely for its own sake, particularly invention that goes to great lengths to seem authentic or authoritative, academic even. The great precursor here is Borges’ short story ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ which relates the invention of a Britannica-style encyclopedia describing with the greatest detail and authority a completely fictional world. Typically for Borges (as for Harrison), the story is also a commentary upon this kind of invention, as well as the effect it can have on our “real” world—for Borges and Harrison reality is more mutable than people like to think. Luigi Serafini takes the whole game a very difficult step further, by creating a complete work which describes his own fictional world in detail, with numerous colour illustrations and the whole written in a completely invented language and alphabet. I’ve never seen a comment by Borges that refers to the Codex but I’m sure he would have been delighted by it.

The Codex was first drawn to my attention not by Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadaluppi’s excellent Dictionary of Imaginary Places (where it would be excluded anyway, since it doesn’t concern a place located on the Earth) but in a book by computer scientist Douglas R. Hofstadter called Metamagical Themas. Hofstadter won the Pulitzer Prize for non fiction with his first book, Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. Metamagical Themas is a collection of essays he wrote for Scientific American in the early 1980s when he took over the ‘Mathematical Games’ column previously written by Martin Gardner (Hofstadter’s title is an anagram.) Although Hofstadter’s books tend to focus on scientific and mathematical subjects, he is, like many of the best scientists, fascinated by the point at which logic grows fractal and meaning devolves into subjectivity. An essay entitled ‘Stuff and Nonsense’ discusses the nonsense tradition from Ben Johnson through to Samuel Beckett and John Lennon. Towards the end of the piece he describes the Codex:

The Codex was first drawn to my attention not by Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadaluppi’s excellent Dictionary of Imaginary Places (where it would be excluded anyway, since it doesn’t concern a place located on the Earth) but in a book by computer scientist Douglas R. Hofstadter called Metamagical Themas. Hofstadter won the Pulitzer Prize for non fiction with his first book, Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. Metamagical Themas is a collection of essays he wrote for Scientific American in the early 1980s when he took over the ‘Mathematical Games’ column previously written by Martin Gardner (Hofstadter’s title is an anagram.) Although Hofstadter’s books tend to focus on scientific and mathematical subjects, he is, like many of the best scientists, fascinated by the point at which logic grows fractal and meaning devolves into subjectivity. An essay entitled ‘Stuff and Nonsense’ discusses the nonsense tradition from Ben Johnson through to Samuel Beckett and John Lennon. Towards the end of the piece he describes the Codex:

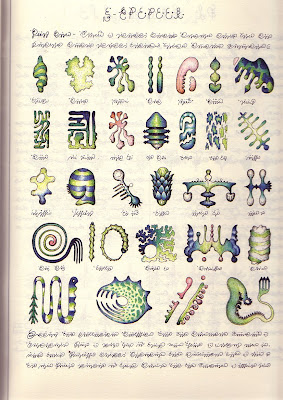

Codex Seraphinianus is a much more elaborate work. In fact, it is a highly idiosyncratic magnum opus by an Italian architect indulging his sense of fancy to the hilt. It consists of two volumes in a completely invented language (including the numbering system, which is itself rather esoteric), penned entirely by the author, accompanied by thousands of beautifully drawn colour pictures of the most fantastic scenes, machines, beasts, feasts, and so on. It purports to be a vast encyclopedia of a hypothetical land somewhat like the earth, with many creatures resembling people to various degrees, but many creatures of unheard-of bizarreness promenading throughout the countryside. Serafini has sections on physics, chemistry, mineralogy (including many drawings of elaborate gems), geography, botany, zoology, sociology, linguistics, technology, architecture, sports (of all sorts), clothing, and so on. The pictures have their own internal logic, but to our eyes they are filled with utter non sequiturs.

A typical example depicts an automobile chassis covered with some huge piece of what appears to be melting gum in the shape of a small mountain range. All over the gum are small insects, and the wheels of the “car” appear to have meIted as well. The explanation is all there for anyone to read, if they can decipher Serafinian. Unfortunately, no one knows that language. Fortunately, on another page there is one picture of a scholar standing by what is apparently a Rosetta Stone. Unfortunately, the only language on it, besides Serafinian itself, is an unknown kind of hieroglyphics. Thus the stone is of no help unless you already know Serafinian. Oh, well… Many of the pictures are grotesque and disturbing, but others are extremely beautiful and visionary. The inventiveness that it took to come up with all these conceptions of a hypothetical land is staggering.

Subsequent research on my part revealed that, although the estimable Manguel makes no mention of the Codex in his Dictionary of Imaginary Places, he was in fact (inevitably?) present at the book’s public discovery, an event he describes in A History of Reading:

Subsequent research on my part revealed that, although the estimable Manguel makes no mention of the Codex in his Dictionary of Imaginary Places, he was in fact (inevitably?) present at the book’s public discovery, an event he describes in A History of Reading:

One summer afternoon in 1978, a voluminous parcel arrived in the offices of the publisher Franco Maria Ricci in Milan, where I was working as a foreign language editor. When we opened it we saw that it contained, instead of a manuscript, a large collection of illustrated pages depicting a number of strange objects and detailed but bizarre operations, each captioned in a script none of the editors recognized. The accompanying letter explained that the author, Luigi Serafini, had created an encyclopedia of an imaginary world along the lines of a medieval scientific compendium: each page precisely depicted a specific entry, and the annotations, in a nonsensical alphabet which Serafini had also invented during two long years in a small apartment in Rome, were meant to explain the illustrations’ intricacies. Ricci, to his credit, published the work in two luxurious volumes with a delighted introduction by Italo Calvino; they are one of the most curious examples of an illustrated book I know. Made entirely of invented words and pictures, the Codex Seraphinianus must be read without the help of a common language, through signs for which there are no meanings except those furnished by a willing and inventive reader.

To Ricci’s further credit, the book is still essentially in print, albeit at a price most people would find prohibitive.

As Hofstadter says, the mind is indeed staggered when considering the labour that went into the creation of this work, particularly for something that, in its willful hermeticism, subscribes to the Brian Eno recipe for originality: do something that’s so time-consuming or difficult that no one else would ever bother. If this makes it sound like a slightly more involved equivalent of those Guinness Record-competing constructions made of toothpicks, then the comparison is unfair. The Taj Mahal in matchsticks operates on something like the chimps-with-typewriters principle: any number of people, given enough time, application and boxes of Swan Vesta could do as much. The Codex Seraphinianus is rather more special than that. It may be a folly but, like all the best follies, it achieves its own aesthetic apotheosis through accumulation of detail, sheer inventiveness and the ultimate conviction of its own worth; like all the best follies it is also unique. It might even be argued that the Codex Seraphinianus is one of the purest works of fantasy, one that affects no compromise with supporting narrative or histrionic drama but aims straight for the gold.

As Hofstadter says, the mind is indeed staggered when considering the labour that went into the creation of this work, particularly for something that, in its willful hermeticism, subscribes to the Brian Eno recipe for originality: do something that’s so time-consuming or difficult that no one else would ever bother. If this makes it sound like a slightly more involved equivalent of those Guinness Record-competing constructions made of toothpicks, then the comparison is unfair. The Taj Mahal in matchsticks operates on something like the chimps-with-typewriters principle: any number of people, given enough time, application and boxes of Swan Vesta could do as much. The Codex Seraphinianus is rather more special than that. It may be a folly but, like all the best follies, it achieves its own aesthetic apotheosis through accumulation of detail, sheer inventiveness and the ultimate conviction of its own worth; like all the best follies it is also unique. It might even be argued that the Codex Seraphinianus is one of the purest works of fantasy, one that affects no compromise with supporting narrative or histrionic drama but aims straight for the gold.

If Borges’ story sparked the creation of the book (and it’s a good bet that this was the case), Serafini’s pictures, in style and content, seem to owe much to the cartoons and drawings of another master of baroque European fantasy, Roland Topor. Topor was an equally polymathic figure—cartoonist, writer, film maker—who still seems better known in his native France than elsewhere. He is perhaps best known for his 1964 novel Le Locataire Chimérique, which was brilliantly filmed by Roman Polanski in 1976 as The Tenant. He also collaborated with René Laloux for the animated feature La Planète Sauvage and can be seen portraying an appropriately unhinged Renfield in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre. Topor and Serafini share a certain naïve draughtsmanship which nonetheless is in the service of an enthusiastic and deliberately Surrealist (in the original sense of the term) level of invention. Topor’s bizarrely costumed characters created for the apocalyptic Ligeti opera Le Grande Macabre could have stepped directly from the pages of the Codex; the worlds of La Planète Sauvage, their inhabitants and creatures, buildings and habits, could conceivably occupy the same solar system as Serafini’s although Serafini’s imagination lacks Topor’s viciousness.

If Borges’ story sparked the creation of the book (and it’s a good bet that this was the case), Serafini’s pictures, in style and content, seem to owe much to the cartoons and drawings of another master of baroque European fantasy, Roland Topor. Topor was an equally polymathic figure—cartoonist, writer, film maker—who still seems better known in his native France than elsewhere. He is perhaps best known for his 1964 novel Le Locataire Chimérique, which was brilliantly filmed by Roman Polanski in 1976 as The Tenant. He also collaborated with René Laloux for the animated feature La Planète Sauvage and can be seen portraying an appropriately unhinged Renfield in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre. Topor and Serafini share a certain naïve draughtsmanship which nonetheless is in the service of an enthusiastic and deliberately Surrealist (in the original sense of the term) level of invention. Topor’s bizarrely costumed characters created for the apocalyptic Ligeti opera Le Grande Macabre could have stepped directly from the pages of the Codex; the worlds of La Planète Sauvage, their inhabitants and creatures, buildings and habits, could conceivably occupy the same solar system as Serafini’s although Serafini’s imagination lacks Topor’s viciousness.

The Codex Seraphinianus remains a gauntlet thrown down to anyone considering the creation of an imaginary place. Like Finnegans Wake, it probably signifies a dead end, or at least the farthest point anyone would wish to take such an endeavour while remaining sane; even Henry Darger’s monumental Story of the Vivian Girls is written in English! Those of us who might wish to see more works like it are bound to be frustrated for some time yet. The best we can hope for is a paperback reprint from an enterprising publisher, something to popularise it a little more. Four hundred full-colour pages in an unknown language with no story—any takers?” - John Coulthart

«MAN AND WOMAN COPULATE, TURN INTO ALLIGATOR

«MAN AND WOMAN COPULATE, TURN INTO ALLIGATOR

Like a Borges story, this is as much about the quest for knowledge as it is about the knowledge itself. It involves books missing from libraries, lost translations, and people not answering letters. But I’m already getting ahead of myself. Let me start by telling you the story of how the Codex Seraphinianus came into my life.

At the beginning of my junior year of college, some friends and I came across an upper-division English class called Eccentric Spaces and Spatialities. No matter how many times we read the course description (sample sentence: “To ask if [Charles] Fort ‘really’ meant to claim that the heavens are chock-full of angels, frogs, and other junk is to miss a broader significance of eyewitness testimony that the sky is falling”), we couldn’t figure out what the class was about. So we all signed up.

Dr. Terry Harpold was a screwy, passionate genius whom I sort of fell in love with. The breadth and intricacy of his thought were offset by a rigorous self-doubt that seemed at first to be affected but was actually in earnest. He once apologized because “my German isn’t what it could be” before quibbling with the English translation of a Freud essay. He seemed to embody everything magical and erudite about the life of the academic postmodernist, which, at that time, was more or less what I wanted to be.

One day Dr. Harpold came to class visibly excited. He said he had found a very rare, delicate, and expensive book just sitting on the shelf at the university library. It was typical, he said, because the few libraries that owned a copy of this rare book didn’t know how valuable it had become, so it got shelved with the general collection and subsequently stolen by the first savvy person who came upon it. Harpold had caught our university library’s grievous error and had had it corrected, but not before pulling faculty privilege and checking it out himself. After admonishing us to make sure our hands were clean, he passed it around. “It” was a book called Codex Seraphinianus, by one Luigi Serafini, published in an extremely limited edition in Italy in 1981. The book was an oversize black hardback. The cover art was a vaguely encyclopedic depiction of a man and a woman engaged in successive stages of copulation, then melding together, and finally becoming a single alligator.

When the book came to me I opened to a random page.

I saw a flattish doughnut, possibly made of liquid, and colored a soft, rich red. While the doughnut’s inner ring (i.e., the perimeter of the doughnut’s hole) was perfectly round, the outer ring was irregularly shaped, and appeared more like an elastic membrane. Ladybugs, the same color as the doughnut but also stippled with their standard black dots, emerged from the outer ring and crawled off in all directions. On closer inspection, it didn’t appear that the ladybugs had pushed through the membranous outer ring; no, it seemed more like they were forming from the doughnut material. Parts of the doughnut’s outer ring appeared scooped out, and these inlets seemed to correspond to the various fully formed ladybugs that had walked away.

Below, in another, smaller illustration that seemed to accompany the above-described, nearly twenty red rings of various sizes were strung like beads on the upper branches of a seemingly normal, if nonspecific, tree. The sky was a gauzy patchwork of light blue and white, the clouds skinny and long.

Text accompanied these images—or what looked like text. But the text wasn’t in English, and it wasn’t anything recognizably foreign like, say, Arabic or Sanskrit, though those analogs immediately came to mind. Though impenetrable, a kind of meaning was suggested by the layout of the script on the page. This was reinforced by the visual resonances of the two images and their apparent or implied relationship to one another. The ladybug doughnut, which dominated the whole top half of the page, seemed to be a natural process, a sort of variation on the butterfly chrysalis, though in this case a multitude of creatures was formed in (but also, importantly, of) some protean organic material (perhaps a visual pun on the idea of a “primordial soup”) that collected in shapely rings around tree limbs, at least in the environment under consideration. Toward the bottom of one “paragraph” on the page were four dollops of color, ranging from a whitish beige to the same red as that of the rings. Perhaps the text was explaining how to gauge the rings’ progress in the incubation/gestation cycle. Since the rings on the tree were all final-stage red, and the leaves on the tree were so green, you could surmise that it was spring in the picture, and the rings were getting ready to burst forth with new ladybugs. The world, at this level, was wholly internally consistent—or at least it could be made to “read” that way.

The Codex has many pages filled solely with text; as well, it contains many charts, graphs, and lists. Panning back a bit, we see a book that features all the structural components of an encyclopedia. The ladybug doughnut is one of hundreds of illustrations from the flora and fauna sections of the book (more on this in just a bit), which warrant comparison with Pliny’s Natural History, Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, and taxonomical surveys in general. Later in the book, as Serafini shifts his focus to depictions of objects, customs, cultures, modern landscapes, and scenes from life, the referential matrix likewise shifts from Edward Lear–like surrealist naturalism to a mélange including Hieronymus Bosch, the engravings of the great (also heretical, samizdat) alchemical manuals of European history, some Dada, and ’70s pop art.

The chances that one might own, via theft or more legal means, one’s own copy of the Codex have increased even since my days as a college junior; the internet has made the word rare a relative term. A few French booksellers sell the Codex on their websites, and though new editions tend to run only a few hundred copies, it does occasionally pop back into print in this or that country. Older editions are consistently available on eBay and Amazon, though never in great quantities and at vastly divergent prices. I’ve seen them sell for upward of a grand, and for as low as one hundred dollars. Eventually I came to own a Codex of my own, via eBay, in an auction that I’d watched sit at just under two hundred dollars for days. With fifteen minutes remaining, somebody bumped it up five dollars. A vicious showdown ensued. Outbid with a minute to go, I waited until there were ten seconds left, then put down a final bid, figuring—rightly—that the auction would end on my bid before dude could refresh his page.

The chances that one might own, via theft or more legal means, one’s own copy of the Codex have increased even since my days as a college junior; the internet has made the word rare a relative term. A few French booksellers sell the Codex on their websites, and though new editions tend to run only a few hundred copies, it does occasionally pop back into print in this or that country. Older editions are consistently available on eBay and Amazon, though never in great quantities and at vastly divergent prices. I’ve seen them sell for upward of a grand, and for as low as one hundred dollars. Eventually I came to own a Codex of my own, via eBay, in an auction that I’d watched sit at just under two hundred dollars for days. With fifteen minutes remaining, somebody bumped it up five dollars. A vicious showdown ensued. Outbid with a minute to go, I waited until there were ten seconds left, then put down a final bid, figuring—rightly—that the auction would end on my bid before dude could refresh his page.

I got my Codex for the relative bargain of two hundred and seventy-five dollars. It’s the 1983 Abbeville Press edition, the only American edition of the book ever printed. “Organized in eminently logical fashion,” the jacket copy tells me, “it describes a system of knowledge that—at least in its structure—mirrors our own: here are botany, zoology, chemistry, physics, engineering, anatomy, anthropology, sociology, linguistics, and urban studies, each describing its object with a peculiarly recognizable exactitude.” It continues, in a tone not unlike that of a carnival barker: “Discover for yourself, reader, such wonders as the purple-caged citrus, the spider-web flower, the parfait protea, and the ladder weed. This is a world inhabited by weird half-sentient flora such as the tadpole tree and the meteor-fruit, by the lacy flying-saucer fish, the wheeled caterpillar-rumped horse, and the metamorphic bicranial rhino. The planet’s sentient species are here as well—races like the Garbage-Dwellers, the Road-Traffic and the Yarn People, and the exotic Rodent-Skin Wearers… Nor can we forget to mention the Homo-Saurians, whose unusual sexual life-cycle is graphically described.” One presumes the “Homo-Saurians” are the couple-cum-gator on the book’s cover (the illustration also appears inside the book). The jacket copy cheerfully concludes that “merely to name these creatures is to confront the limits of our language.” Well, yeah.

History is littered with inscrutable texts. Some have been deciphered, others—in terms of origin, content, and purpose—remain mysterious. As a book-object, though, the Codex’s only real precursor is The Voynich Manuscript. Discovered by the Polish book collector Wilfrid M. Voynich in a wooden chest at an Italian Jesuit college in 1912, the heavily illustrated manuscript was worked on by top code-crackers during World War II. They failed. It’s never been deciphered. Theories on its origin and significance abound, including the theory that the manuscript is a fraud perpetrated by Voynich himself, but the most popular and conclusive theory attributes the work to Roger Bacon, the medieval Franciscan friar who, in his Letter Concerning the Marvelous Power of Art and Nature and the Nullity of Magic, noted that “certain persons have achieved concealment by means of letters not then used by their own race or others but arbitrarily invented by themselves.”

When I realized that the Codex was going to turn twenty-five years old in 2006, I decided to track Serafini down.

When I realized that the Codex was going to turn twenty-five years old in 2006, I decided to track Serafini down.

Here is his Wikipedia entry, in full:

'Luigi Serafini is an Italian graphic artist famous for his unusual and obscure works such as the Codex Seraphinianus. Born in Rome in 1949, Serafini began his career as an architect before creating the Codex Seraphinianus; he also authored the Pulcinellopedia Piccola. Serafini has also worked with the media of industrial design, film, and theater, and has also written stories for Italian magazines.

...With the author himself apparently out of the picture, I decided to try and get some art-historical context for the book and its elusive author. I wrote to Arthur C. Danto, art critic for the Nation, and described the book to him. He was intrigued and invited me to his apartment. “This is just astounding,” he said when I took the book out of its special protective plastic grocery bag. “I’ve never come across anything like this at all.” Then: “Boy, you’re gonna be lost for a while.”

In Borges’s Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, the narrator navigates a standard Borgesian labyrinth of encyclopedia entries and letters in an attempt to learn about the region of Uqbar, a place with uncertain borders thought to be located somewhere between Iraq and Asia Minor. What comes to occupy him instead is a book titled A First Encyclopedia of Tlön, an exhaustive documentation of an apparently imaginary world created by the Uqbaris. “I had in my hands a substantial fragment of the complete history of an unknown planet,” the narrator writes of the volume, “with its architecture and its playing cards, its mythological terrors and the sound of its dialects, its emperors and its oceans, its minerals, its birds, and its fishes, its algebra and its fire, its theological and metaphysical arguments, all clearly stated, coherent, without any apparent dogmatic intention or parodic undertone.” Save that last part about the parodic undertone, what we have here is a serviceable summary of the Codex Seraphinianus.

In Borges’s Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, the narrator navigates a standard Borgesian labyrinth of encyclopedia entries and letters in an attempt to learn about the region of Uqbar, a place with uncertain borders thought to be located somewhere between Iraq and Asia Minor. What comes to occupy him instead is a book titled A First Encyclopedia of Tlön, an exhaustive documentation of an apparently imaginary world created by the Uqbaris. “I had in my hands a substantial fragment of the complete history of an unknown planet,” the narrator writes of the volume, “with its architecture and its playing cards, its mythological terrors and the sound of its dialects, its emperors and its oceans, its minerals, its birds, and its fishes, its algebra and its fire, its theological and metaphysical arguments, all clearly stated, coherent, without any apparent dogmatic intention or parodic undertone.” Save that last part about the parodic undertone, what we have here is a serviceable summary of the Codex Seraphinianus.

Danto, when coaxed to respond to the Codex, tossed out Isidore of Seville, the entire history of scientific illustration, Breton’s futile attempts to introduce a new letter to the French alphabet, the Codex Leonardo (da Vinci, that is), and the writings of Borges and Italo Calvino. Though he was quick to qualify his list with the disclaimer that it was all just off the cuff, free association, really, he turned out to have pretty much hit it on the head.

You can go through the book page by page, as I have, but the sensation of discovery never entirely goes away. Also, as with any artistic or literary work, the viewer/reader’s mood and mind-set have a substantial—if not constitutive—effect on the reading and interpretation. Isn’t every piece of art a kind of inkblot? Flipping through the book one day, I was struck by a depiction of what appeared to be a burial custom. A motionless, nondescript man in a black suit is lying on a table. In the next illustration, the table is gone and the man is inside a rectangular block of what looks like glass. The bottom half of the page is taken up by an almost pastoral scene. It looks like a public park, but with low walls and squat buildings constructed of the glasslike blocks, each of which contains a person. On a mall of kempt green grass, neat rows of freestanding blocks look like sculptures in a garden. There are trees. People walk alone or in small groups through a large, simple arch (constructed likewise of the transparent, occupied blocks) into what is apparently an outdoor mausoleum of some sort. It made me think of Richard Brautigan’s book In Watermelon Sugar (1968), where the dead are buried in glass coffins lined with fox fire, so that they will shine forever.

You can go through the book page by page, as I have, but the sensation of discovery never entirely goes away. Also, as with any artistic or literary work, the viewer/reader’s mood and mind-set have a substantial—if not constitutive—effect on the reading and interpretation. Isn’t every piece of art a kind of inkblot? Flipping through the book one day, I was struck by a depiction of what appeared to be a burial custom. A motionless, nondescript man in a black suit is lying on a table. In the next illustration, the table is gone and the man is inside a rectangular block of what looks like glass. The bottom half of the page is taken up by an almost pastoral scene. It looks like a public park, but with low walls and squat buildings constructed of the glasslike blocks, each of which contains a person. On a mall of kempt green grass, neat rows of freestanding blocks look like sculptures in a garden. There are trees. People walk alone or in small groups through a large, simple arch (constructed likewise of the transparent, occupied blocks) into what is apparently an outdoor mausoleum of some sort. It made me think of Richard Brautigan’s book In Watermelon Sugar (1968), where the dead are buried in glass coffins lined with fox fire, so that they will shine forever.

Is the connection legitimate, which is to say, intended by Serafini as a direct reference? Probably not. On a different day, would I even have thought of Brautigan? Doubtful.

It’s also possible that the text means in a way which trumps our ability to understand it, which is not the same as it not meaning at all. “It’s hard for me to imagine someone dedicating themselves to producing page after page of what looks like writing without it being writing, just for that purpose,” Jackson said. Looking over the pages of unillustrated Serafinian script, then and now, I am inclined to agree with her. “It makes me wonder whether there is a private significance to it.”

Late in the book there is an image of a man standing next to something that looks like a Rosetta stone. He is dressed like a laid-back professor, a sport coat and jeans, very ’70s. He holds a strange pointer up to the stone, which is a bit taller than he is, and broken at the top. You can see into the stone, which is not solid rock but filled with something very red. It reminds me of blood or magma or a tongue. The professor has another pointer in his other hand and its end is jammed into the red stuff. The face of the stone is divided into two columns of text. One side is all Serafinian script, the other appears to be a kind of hieroglyphics. This image is the first illustration in the book’s “chapter” on language—in the following pages, question marks become fishing hooks; words float off the page, tied to punctuation marks that have become colored balloons; swoops of script are magnified exponentially, allowing us to see that what we took to be plain black ink is actually a whole world teeming with microscopic schools of fish, cars rounding a tight curve, Dante-esque pillars of intertwined human bodies (or are they souls?).

But back to the Rosetta stone: it’s an incredibly provocative image because it takes the issue of deciphering or translating, already a foregrounded concern, and throws it in your face. The instinct is to think that this image is the key to the Serafinian code/language, that all you need to do is find the clue and you’ll be set. But that kind of thinking is a logical misstep. The Codex Seraphinianus purports not simply to be about another world but also to be a document from that world. The image is concerned with the translation of the hieroglyphics, not the Serafinian script, which any intended reader of the Codex would already know well. Further complicating things is that the hieroglyphics appear to be crude approximations of a couple hundred amoebic creatures depicted much earlier in the book. Divided into three categories, or genera (fire/electricity, plant/earth, rainbow), these seemed to me to be the most basic forms of life in the Serafinian world. This suggests again the work of the alchemists, who believed everything to be alive in its own way, but the creatures themselves look like something only visible with a microscope. We know from the above-described close-ups of text (and other images in the book) that the Serafinians have microscopes, all sorts of technology, in fact, but it hardly makes sense that their ancient, stone-carving predecessors would have. Perhaps the ancients had other skills, metaphysical ones, which allowed them to see the unseeable and base a pictographic language on it.

“You could keep formulating theories ad infinitum,” Jackson said, “without them resolving into anything, or without them reaching closure, at least, which is frankly the most interesting thing about it.”

S. E. Grant, a student of Shelley Jackson’s and a friend of mine, had expressed early interest in my project, so when I’d come across the French fragments of Calvino, I’d sent them to her to translate... S.E. did her own original translation of the Calvino for me, and as far as I know it is the first complete rendering of that text into English... “Orbis Pictus” runs about eighteen hundred words in English. Not surprisingly, it is the most elucidative piece of Codex-related writing I have ever come across, and deserves to be published on its own somewhere. But, since I can’t just fiat that into happening, I’d like to quote quite a bit of the beginning:

S. E. Grant, a student of Shelley Jackson’s and a friend of mine, had expressed early interest in my project, so when I’d come across the French fragments of Calvino, I’d sent them to her to translate... S.E. did her own original translation of the Calvino for me, and as far as I know it is the first complete rendering of that text into English... “Orbis Pictus” runs about eighteen hundred words in English. Not surprisingly, it is the most elucidative piece of Codex-related writing I have ever come across, and deserves to be published on its own somewhere. But, since I can’t just fiat that into happening, I’d like to quote quite a bit of the beginning:

'In the beginning, there was language. In the universe Luigi Serafini inhabits and depicts, I believe that written language preceded the images: beneath the form of a meticulous, agile, and limpid cursive (and strength lies in admitting it is limpid), that we always feel on the point of deciphering them just when each word and each letter escapes us. If the Other Universe communicates anguish to us, it’s less because it differs from ours than because it resembles it: the writing, in the same way, could have developed very similarly to ours in a linguistic forum that is unknown to us, without being altogether unknowable.… Serafini’s language does not distinguish itself only by its alphabet, but also by its syntax: the objects of this universe evoke the language of the artist, such as we see them illustrated in the pages of his encyclopedia, and are almost always identifiable, but their mutual relations appear psychologically disturbed to us by their unexpected relationships and connections.… Here is the conclusive point: endowed with the power to evoke a world in which the syntax of things is subverted, the Serafinian writing must hide, beneath the mystery of its indecipherable surface, a more profound mystery touching on the internal logic of language and thought. The lines that connect the images of this world tangle and cross; the confusion of the visual attributes gives birth to monsters, Serafini’s teratological universe. But the teratology itself implicates a logic which appears to us to, turn by turn, flower and disappear, at the same time giving us the sense that the words are carefully traced back to the point of the quill. Like Ovid, and his Metamorphoses, Serafini believes in the contiguity and permeability of all the domains of being.'

If I have one quibble with the Calvino introduction, it is that it perhaps explains too much. To the list of influences and/or references, he adds the Botanica Parallela of Leo Lionni, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, “Bruno Munari and the entire line of inventors of crazy machines.” He too notices the visual resonance of the hieroglyphics on the would-be Rosetta stone with the little creatures he refers to as the “polychromatic corpuscles” from the early part of the book. Maybe “they constitute again another alphabet,” he writes, “more mysterious and more archaic.” And maybe they do, but any readers who read his introduction would have spoiled for themselves the fun of discovering (or not discovering) that fact on their own.

Of course the same charge could potentially be leveled against this essay. Maybe this isn’t so much like a Borges story after all. As the internet and other technologies continue to forward the process that Paul Virilio correctly—if rather a bit hysterically—refers to as “the pollution of distances,” one notable side effect is the obsolescence of proximity. Forget the years that the European alchemists of old would have spent copying over their heresies, in secret and by hand, and then the subsequent crisis of dissemination.

...Calvino.. goes so far as to suggest a narrative framework within which to understand the Codex’s genesis and production. “At the end of the tally (see the last page of the Codex) the destiny of all writing is to decay into dust; only the skeleton of the hand that writes survives. Lines and words detach from the page, breaking away, and here the tiny motes of dust spew forth the colored corpuscles from the rainbow, which then begin to frolic. For the vital principle of all the metamorphoses and all of the alphabets, a new cycle begins.” It is just as reasonable to celebrate Calvino’s introduction as an intentional redoubling of the book’s mystery as it is to chide it for being a would-be master narrative. Though his words have the authority of his name and an aura of truth surrounding them, it is a nonexclusive truth which they emanate. Calvino may be correct, probably is correct, but his correctness does not come at the expense of the correctness of any other potential reading. His authority is that of the sage, not that of the monarch.

I’ll withdraw my quibble with Calvino, then, but I prefer to end on a line not from him but from Borges once more: “The metaphysicians of Tlön are not looking for truth, nor even for an approximation of it; they are after a kind of amazement. They consider metaphysics a branch of fantastic literature.”» - Justin Taylor

"Read" it online at: http://issuu.com/dylan_k/docs/luigi.serafini.-.codex.seraphinianus

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.