Mark Dery, I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts: Drive-By Essays on American Dread, American Dreams, University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

"From the cultural critic Wired called “provocative and cuttingly humorous” comes a viciously funny, joltingly insightful new collection of drive-by critiques—of an America gone mad, and a world where chaos and catastrophe are the new normal.

Here are essays on the pornographic fantasies of Star Trek fans; Facebook as Limbo of the Lost; George W. Bush’s fear of his inner queer; the theme-parking of the Holocaust; the homoerotic subtext of the Superbowl; the hidden agendas of I.Q. tests; Santa’s secret kinship with Satan; the sadism of dentists; Hitler’s afterlife on YouTube; the sexual identity of 2001’s HAL; the suicide note considered as a literary genre; the Surrealist poetry of robot spam; the zombie apocalypse; Lady Gaga; the Church of Euthanasia; toy guns in the dream lives of American boys; and the polymorphous perversity of Madonna’s big toe.

From Menckenesque polemics on American society to deft deconstructions of pop culture to unflinching personal essays in which the author turns his scalpel-sharp wit on himself, I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts is a head-spinning intellectual thrill ride."

"Mark Dery’s cultural criticism is the stuff that nightmares are made of. He’s a witty and brilliant tour guide on an intellectual journey through our darkest desires and strangest inclinations. You can’t look away even if you want to." — Mark Frauenfelder and David Pescovitz

"Mark Dery is gifted with sanity, humor, learning, and a prose style as keen as a barber’s razor. He applies those qualities to a trustworthy and entertaining analysis of the lunatic fringe, which constitutes an ever-larger portion of the discourse in America today." — Luc Sante

"For the last couple of decades Mark Dery has been investigating the cutting-edge of American culture and counterculture with an eye at once empathic and horrified, thrilled with the creatively liberating possibilities of the future and dismayed at the still-powerful sway of the forces of corruption and bigotry. His original takes on such familiar fodder as Star Trek or 2001: A Space Odyssey and his revealing accounts of his youth and the cultural and political milieu in which he grew up, a lonely kid made an outsider by his intellectual gifts and lack of sympathy with the mainstream (the introduction, Gun Play), show how the political and the personal, the sign and the hidden ideology, are inextricably interlinked, whether we realise it or not. I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts is a collection of his essays, published online and elsewhere, ranging chronologically from the late 90s up to 2010, chronicling his take on American Gothic: ‘...the stomach-plunging drop from reassuring myth to ugly truth – the distance between our dream of ourselves and the face staring back at us from the cultural mirror’; and ranging in subject matter from the ‘resurrection’ of Mark Twain to the disturbing imagery of online snuff movies.

Dery is a postmodern Ancient Mariner who has plied the vast and depthless oceans of contemporary American culture and politics and come back to buttonhole us all, just as we’re on the way in to the party, to show us that there is unimaginable darkness and insanity Out There. It would behove us to heed his warnings, because it looks like the Late Capitalist/Liberal Democracy party may be soon over.

Well, ok, he may not be quite as apocalyptic as that star of the ‘what do we do in the post-ideological era’ essay Slavoj Zizek (who wins my award for World’s Twitchiest Philosopher), but he’s a damn sight more readable. There is, however, a tinge here and there of Frankfurt School pessimism about mass culture which, to my mind, is a little one-sided. (Culture, mass or high, is always a mixture of curse and blessing, in my view – but enough of my cheery Anarchist digressing), but even in his philippics against Web culture (World Wide Wonder Closet, Face Book of the Dead) he puts forward a view that has been seriously considered and should be taken account of. Anyway, that being said, he’s an astute plumber of the semiotic depths hidden beneath the surface of the meme pool. Every chapter, indeed almost every page, adduces evidence that we are heading inexorably towards the Post-American Century. Decadence abounds – how fast this mighty nation has fallen from burgeoning postcolonial republic, through ne plus ultra of empire builders, to fading power upon which the sun of global domination is ineluctably setting. That, depending on your point of view, is either something to bemoan or celebrate. Dery, being a good Neo-Marxist-influenced critic, I suspect adheres sensibly to the latter view.

There’s at least one zinger on every page, some penetrating aperçu couched in a piece of ROFL wordplay. But the puns are layered, condensing two or three ideas into one quotable nugget, linking disparate images to underline their connectivity in the contemporary imagination. Dery certainly knows how to create an effectively condensed heuristic – which is just a fancy way of saying he’s pithy and informative, I guess. In fact, I have the impression that humour has become a more significant element in his style over the years. I went back to my copy of his early work Escape Velocity: Cyberculture and the End of the Century and my perusal confirmed this view. His prose has taken on a swinging, grooving cadence, a lightness, that is nascent in the earlier book and pretty much fully blown in the earliest essays in IMNTBT.

But the humour, often mordant in tone, is only part of Dery’s critical armoury. The moral seriousness underlying everything he writes is shown up most perspicuously in a startling switch he pulls off at the end of Shoah Business, a controversial but unflinching essay on the commodification and ideological misuse of the Holocaust and the discombobulating experience of eating in the cafeteria at the State Museum of Auschwitz. (This particularly chimed with me as someone who has undergone the severe cognitive dissonance of receiving a postcard from Auschwitz sent by a family member. It is impossible to adjust one’s mind to such a monstrous juxtaposition of ideas.) He subverts his apparently final judgement with a peripeteia that reminds us, to paraphrase the Situationist dictum, that there is a sleeping Nazi inside every one of us. A chillingly salutary reminder indeed.

Dery is a highly adept semiotician, writing with a rock ‘n’ roll swagger (the book’s title is from a song by LA psychobilly post-punk band X) but working within a dauntingly wide scope of scholarly reference, channelling culture both high and low, showing us new things in the familiar tropes of mass culture (the Super Bowl) and opening up the marginalia of American life too (the suicide note as literary artefact). Indeed, I am indebted to Dery for introducing to me the work of psychedelic philosopher Terence McKenna, tell-it-like-it-is zoologist Gordon Grice and whacky Christian pamphleteer and cartoonist Jack Chick, inter alia. I’m also grateful for the final word on that putative tool of the Bavarian Illuminati Lady Gaga. I could never make up my mind whether she was a force for good or evil or just another pop singer. Well it turns out she’s A Bad Thing. And it’s always good to see Madonna and her high priestess Camille Paglia (do people still read or listen to her?) get a lambasting.

The fact that the book opens with epigraphs from JG Ballard and Don Delillo is a welcome clue that this is not going to be some ponderous collection of theory-heavy, nigh-unreadable academic prose but a forward-looking, accessible-but-not-dumb journey through the good, the bad and the ugly of that great simulacrum called the USA. And that word ‘simulacrum’ is apt: Dery more than once references Baudrillard, another of the presiding spirits, in company with Ballard, Delillo, Mencken, Adorno, Horkheimer, Orwell, David Lynch and Lester Bangs, watching over Dery’s shoulder as he gets all Ciceronian on Postmodernity’s ass. That these wits, thinkers and dreamers inform Dery’s worldview is all to the good; his spirit (sorry to flout Mark’s materialist ethic here) is at one with theirs. I can’t put it any better than Bruce Sterling, who in his thoughtful preface describes Dery’s work as ‘an intellectual insurgency against the friendly fascisms of right and left, happy bedfellows in their prohibition, on pain of death, of thoughtcrime.’ In short, Mark Dery is my kind of public intellectual.

More relevant than Mythologies, funnier than Travels in Hyperreality, more readable than Simulacra, less gloomy than Living in the End Times, smarter than Hitchens and without the pomposity, Dery’s dazzling collection will, I unhesitatingly predict, become a classic of cultural criticism." - Jim Lawrence

"In the introduction to his new book of essays, "I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts: Drive-by Essays on American Dread, American Dreams" (University of Minnesota Press), Mark Dery lays out the foundation that shores up every one of these short, sharp, well-turned pieces: American Gothic, as epitomized by director David Lynch in the movie Blue Velvet.

"By the American Gothic," Dery writes, "I mean the stomach-plunging drop from reassuring myth to ugly truth -- the distance between our dreams of ourselves and the face staring back at us from the cultural mirror."

Basically, Dery wants to turn society over and shine some light on the dark, crawly things growing underneath it - and us. And he wants to do this not only because he thinks it helps us understand ourselves, but because he believes in intellectual freedom, and "intellectual freedom is unimaginable without the right to think the unthinkable."

"Thinking Bad Thoughts," he says, "is an intellectual insurgency against the friendly fascisms of right and left."

Dery is farther left than right - he refers to himself as occupying "a sniper's perch on the post-Marxist left" -- but he's willing to take on idiocy wherever he finds it. And he approaches every new episode of idiocy in the same pragmatic, entertaining, no-bullshit way regardless of its origin, whether he's debunking the popular notion of Mark Twain as a benign all-American sage and demonstrating that Twain is the man from whom William S. Burroughs and Hunter S. Thompson learned their "close-quarter knife-fighting skills," or knocking Lady Gaga down a few pegs in "Aladdin Sane Called. He Wants His Lightning Bolt Back," while acknowledging that the "Bad Romance" video shows "real promise....it's Marilyn Manson's Mechanical Animals, as reimagined by Matthew Barney."

In this wide-ranging collection of essays, most of which originally appeared online, Dery takes on Hitler and the Holocaust, Facebook, self-help books, jock culture, the relationship between Satan and Santa (yes, Dery says, there is one), several flavors of porn, and blogging, among other things. In each, he has a way of summing things up in just a few pages that brings the various strands he's been playing with together into one seemingly inevitable and somewhat menacing braid.

In a 2002 essay called "Gray Matter: The Obscure Pleasures of Medical Libraries," for example, he goes from a discussion of the New York Academy of Medicine Library (creepy) to sci-fi noir novelist J.G. Ballard (very creepy), via a Journal of Forensic Sciences article titled "Autoerotic Fatalities with Power Hydraulics" (super creepy), and arrives at this fitting conclusion: "The novelist, then, as society's forensic pathologist."

But Dery wants us to do more than just admire his smarts and his way with words; he actually wants us to join him in thinking hard about stuff that people find it easier not to think about at all, let alone write about.

"Maybe it's time we outgrew our thumb-sucking self-absorption," he writes in "Tripe Soup for the Soul." "Maybe we should ask ourselves: What is our manic pursuit of happiness a flight from? What are our daily affirmations a lucky charm against?"

In the end, what makes Dery such an appealing tour guide through all these bad thoughts of his is that he's right there with us, trying to answer the tough questions, and willing to turn his probing mind and eye on himself, too. It's no wonder that he mentions George Orwell more than once - Orwell, he writes, "lanced the abscesses of his own soul as unflinchingly as he did society's."

And while he may stumble occasionally (an essay on the erotic appeal of Madonna's big toe and foot lust in general shows him slightly less sharp than usual), even his misses will make you look at the world in a whole new and rewardingly disturbing way." - Deborah Sussman

"Essayist, author, cultural critic, blogger (though he despises the term), public intellectual, enfant terrible. Just some of the monikers that have been or could be applied to Mark Dery. Dery has made an art form of the short, punchy and polemical screed. It was through such writing that he single-handedly put epoch-defining terms such as cyberspace and culture jamming into permanent circulation in the 1990s.With the eviscerating Pyrotechnic Insanitarium. American Culture on the Brink (1999) he carved out a new identity for himself as the psychopathologist of the American unconscious. Following all too slowly on its heels I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts (2012) takes us beyond the brink into the maw of something distastefully uncanny, something so horribly real that it can’t possibly exist. CGI cinema certainly has a lot to answer for. What is most appealing about both texts is their composition, by and large, of previously published essays. But this is no cynical commerce. On the contrary, I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts reveals just how ferociously productive Dery has been during the past decade, especially when the final selection is only a snap, or rather sniper shot of the scribbling that the guy churns out. The book brings together essays published in diverse and at times obscure or at least specialized contexts that speak to different demographics and readerships. Collecting them into a single volume concentrates the intensity of the trip we are about to take, rather like pumping up the juice on the electric chair, or getting medieval on the plunger of a lethal injection. In the Pyrotechnic Insanitarium the conjoined metaphor of the theme park and the lunatic asylum gives a thumb nail sketch of the millennial American midway as a freakshow disporting pregnant men, homicidal clowns, cloned sheep and mordant space cults. In Bad Thoughts we are once again privy to a front seat view of the execution chamber where the spectres of American bad faith are gurneyed in for swift despatch at Dery’s merciless hands.

The motif of the “drive-by essay” neatly captures Dery’s sense of what it means to live as a thinking person in America. There’s a shit load going down, it happens real fucking fast and the only way to see it first hand is to get in the Hummer and sit next to the shooter. There’s no time for casuistry here and the “embedded” writer is not simply along for the ride. As he says in the Introduction, he wants to “induce in [his] readers the vertigo that comes from gazing too long into the cultural abyss—then give them a loving shove, right over the edge”.

Dery is clearly the 21st century’s most compelling and readable polymath of the perverse. He trades in American dreams, ranging from old chestnuts like his country’s obsession with guns, the Super Bowl and primal-return-to-wild-nature phenomena such as living with bears and other hopelessly unredeemable critters, the dread of hate-speech shock jocks, the Fantasy Decapitation Channel, the penetrative qualities of dental retractors, and the Church of Euthanasia. Dery writes persuasively on what appear to be left of field non-sequiturs like the death of Pope John Paul II, Facebook, the dark side of Father Christmas and, for me the most extraordinary piece of writing in the book, an essay on the suicide note as a literary genre, “Goodbye, Cruel Words”: “The awful truth (unthinkable to a writer) is that eloquent suicide notes are rarer than rare because suicide is the moment when language fails—fails to hoist us out of the pit, fails even to express the unbearable weight that drags someone about to murder himself down, into endless, silent night”.

But where this book really kicks is with some deliciously mordant themes that seem to have piqued the attention of our author, whom I have characterized here (unashamedly pilfered from Tom Eliot) as the disconsolate chimera, in recognition of his fascination with the absolute cheerless, abject worst America has to offer (a phrase that sounds like the branding for a national cooking show franchise competing for whose cuisine reigns supreme in the name of fast food hell). The idea of the writer as chimera also captures Dery’s shape-shifting ability to move, wraith-like, in and out of America’s dark recesses, consorting with what or who he finds there for a time, then taking his leave without retaining a trace of ordure, slime or malevolence on his nimble feet.

Like the obsessed carny-barker that pulls the punters in The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium, Dery subtly graduates the tour, priming and preparing us for the horrors ahead. He guides us gently by the elbow through the extreme sport banality of zombie walks and the dusty closeness of medical libraries in search of Ballardian “invisible literature.” And when he feels the moment and mood lighting is right, he takes us further down into the musty piquancy of armpit fetishism, clown porn and “sneeze freaks, who rejoice at the thought of a nice, juicy honk, with plenty of spritz.” And did I neglect to mention lactating transsexuals, cuddly necrobabes and scrotal inflation? By now he has prepared us for a descent into the rancorous pit of repugnant fucked-up nastiness, an annotated reading of Adam Parfrey’s Apocalypse Culture. But Dery is no detached, aloof Marlin Perkins-styled anthropological observer (though this book would make a great TV series in the manner of Wild Kingdom but set in the office of Re/Search magazine with Dery as anchor cueing various live links to the crypt of the Capuchins and the cafeteria of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and State Museum). His loathing of Parfrey and his self-styled role as “pitchman on the pathological midway” is worn with pride on the cuffs of the leather jacket he is wont to wear in press photographs:

If he were simply a buck-hungry retailer of the unspeakable, he’d go down easier. But he insists on a more exalted status than the Charles Kuralt of our psychic badlands: that of a Luciferian Noam Chomsky, speaking the awful truths about The Conspiracy and the Dictatorship of Political Correctness that the lapdog mainstream media dare not utter. Unfortunately, it’s well-nigh impossible to reconcile Parfrey’s lofty claims with his mean-spirited “retard” bashing, his seeming endorsement of wet-brained conspiracy theories about Waco, and his creepy coziness with one too many neo-Nazis and Odin-worshipping Aryan supremacists.

One of the real surprises in reading these essays is the occasional tendency towards the autobiographical vignette. In a wonderfully lacerating essay on Lady Gaga’s glam pretensions and conceptual vacuity, Dery let’s the proverbial cat out of the bag and reveals his long-term cerebral identification with David Bowie, and in particular, contra Gaga, his actual knowledge of the cultural references he included in his lyrics. He also shows us his chops in a wonderfully erudite reading of Queen’s “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke.” Contrariwise, once again, he bristles, “Listen to Gaga and you’ll hear the sound of IQ points molting” (the final essay in the book, “Cortex Envy,” is probably the most candidly honest and autobiographical and deals with the subject of our author’s intelligence. Long Silence. Sorry, I don’t read and tell). But be wary, this is no pop-culture-icon bashing. Dery declares his pop and prog rock credentials elsewhere in the book, particularly his discerning taste for Relayer as the apotheosis of the Yes back catalogue. He is simply impatient with the “throbbingly dumb” nature of Lady Gaga’s shtick. In a book about confrontation and extreme conditions he is quick to point that when “Gaga learns that thinking is the most dangerous act of all, she’ll really be one scary monster.” A subsequent essay specifically on his identification with Ziggy and Aladdin (“When did I stop wanting to be Bowie?”) further reveals his capacity for writing solid music criticism; a welcome relief and breath of fresh air, to be sure, from the malodorous depths of cess-pool America and its cults, conspiracy theories, megalomania and, vis. Adam Parfrey, necrophilia, child torture and pedophilia. I ask you does it get any better? This is what Dery calls the American Gothic, a “stomach-plunging drop from reassuring myth to ugly truth – the distance between our dream of ourselves and the face staring back at us from the cultural mirror.”

Bad Thoughts is a truly chilling revelation of all the things you don’t necessarily see in the mainstream media (whatever that means these days). But this is what makes Dery such an ethically important writer. In the Introduction he writes with candour of the writer’s responsibility to think bad thoughts, to “wander footloose through the mind’s labyrinth, following the thread of any idea that reels you in, no matter how arcane or depraved, obscene or blasphemous, untouchably controversial, irreducibly complex, or preposterous on its face.” And that thread, just to be clear, ain’t the one used by Ariadne that helped Theseus navigate the Cretan labyrinth and evade the Minotaur. It is more like a line of nauseous flux, a Burroughsian undifferentiated tissue emanating from the bowels of any-town America, live and coast-to-coast.

The other responsibility that Dery exemplifies with a passion is to writing itself. The great thing about the essay as a form of social and cultural critique is its uncompromising demand on authors to not bore the shit out of the reader. Dery may or may not have affinities with other essayists past and present. I like to situate his writing as a kind of analogue (Eliot would say objective correlative) of the so-called “poison pen” of the 19th century British caricaturist George Cruickshank, whose most famous series of engravings, Monstrosities, lambasted the bombast and grotesque excess he associated with governance, royalty and British society. The measure of this responsibility fulfilled is of course the desire to sustain reading and put off the inevitable sense of an ending that threatens with every sentence. And of course the pleasure in language itself. I can remember many years ago the wonderful miniatures of verbal theatre that readily offered themselves up to be taken hostage in Dery’s writing for 21C and World Art magazines. Of Mike Davis’ City of Quartz, for instance, he observed that “every word… reads as if it were etched in an acid bath.” He describes the lectures of Terence McKenna as “tours de force of verbal virtuosity and packrat polymathy” and Manuel De Landa’s War in the Age of Intelligent Machines as “the internal monologue of a smart bomb seconds from impact.” And if this sounds fannish, it is, and I’m not the only writer on the book who enjoys what Dery does with the English language.

Bruce Sterling’s Foreword to I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts is an astute and deliciously written set piece in its own right. Sure, it more than capably establishes the formaldehyde-infused mise en scène of the hit and run assaults we are in for (“He’s very good at going into areas of culture you wouldn’t care to visit yourself and performing autopsies”), as well as the debt we owe him for drawing our attention to what we normally don’t and certainly never want to see (“This world now looks a lot more like a Mark Dery world than it looked when he started writing”). The zest of Sterling’s text is a testament to Dery’s capacity to bring out the best in other writers, to enable them to not only write memorably, but to infuse every participle of their own writing with the bouquet, piquancy and commitment, no matter how distasteful, of the writing to come: “Having found the cult, he judiciously sips the Kool-Aid.” Like cyanide, that’s it in a nutshell." - Darren Tofts

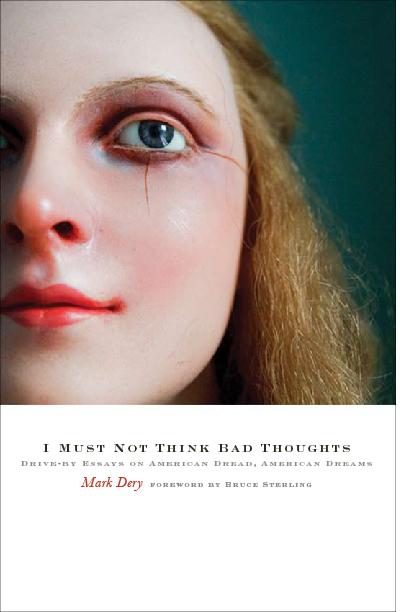

“Voluptuously lustrous and uncannily lifelike,” the antique mannequin on the cover of Mark Dery’s latest essay collection, I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts, ”glows, if not with life, with a robust undeath.” Her skin is so perfect you could eat off the surface of it. Her eye, unbowed, is cracked and bruised, maybe from an injury sustained in the dumpster where they found her before bringing her back to present glory. Reading the book over the last week, she’s had a special place on my pillow, an intellectual “Real Doll,” if you will.

I’ve paid close attention to the work of the writer Mark Dery over the last few years, reading and re-reading a number of his iconoclastic essays in a variety of forums. Yet even I found a smattering of fresh essays I’d not read before in this invigorating new collection of his work.

It’s refreshing to read these essays in book format where they are decoupled from the rabble of internet message boards. Dery inspires strong feelings in readers, and the inevitable arguments that transpire in the comments sections following his posts can be harrowing, and often beside the point. Here, the work stands alone, as it should.

Dery is a gifted prose stylist, performing complex, nuanced analysis of pop culture in his signature, breath-catching style. The sentences are so crisp, they echo in your head, like the sound of someone walking briskly, on the street, after the rain.

Dery treks deep into the many layers of meaning and symbol laden in every subject he sets his sights on. Whether writing about the seedy underbellies of mass culture fixtures like the Super Bowl, toy guns, Lady Gaga, and the Pope, or fringe fascinations like Star Trek porn, dental fetishism, and apocalypse culture, Dery indefatigably explores the the dark matter of our collective unconscious in scholarly, reference-studded strides. Inevitably, he goes just a couple of steps too far in his mad spelunking missions, for my more sheltered eyes, (the fine points of bukaake, for example, are not those I feel particularly enriched by reading about) but I certainly admire the gusto with which he plumbs the depths.

A piece of the mysterious puzzle of my enduring affinity for Dery’s work was suddenly revealed to me in the intriguing 13 Ways of Looking At A Severed Head. Reading this essay, I was gratified to learn that I am not the only one who has harbored recurring fantasies of, to put it delicately, the guillotine treatment to the neck. It’s an extreme thing, I almost never admit it, but then I read the essay and see I am not alone in my peculiar fixation.

What Dery does is take a morbid topic like decapitation and he shines the illuminating light of his scholarship on the subject. We get delicious slivers of fact and anecdote. Did you know a decapitated head maintains consciousness for 13 seconds? What do you suppose those last 13 seconds are like? Dery has studied the art, science and history of the subject and presents it in generous portions. He also considers the limits of our understanding.

“Here is where words wink out like dying stars, lost in the endless night of the unthinkable. Shorn of the organ that makes meaning, the decapitated never ask what a severed head means. Or, perhpas, by losing their heads, they find out at last, but cannot tell us. Their lips tremble, their eyelids flutter, two for yes and one for no, but thirteen seconds is too brief an eternity to tell the living the meaning of life.”

To my mind, Dery is at his most affecting when he writes about his boyhood in Southern California. He describes the specific place and time where he grew up, while capturing something universal about childhood itself.

In Facebook of the Dead, his masterful mash-up of personal history, literary study, and philosophical rumination, Dery captures that feeling of discovery during those moments when our normal frame of reference suddenly expands and we discover something new on the very edge of our previous experience. He leads us through, “creepy, shadowed glades, cloaked by tumbleweeds and wild fennel, that seemed darkly luminous with the paranormal aura of bad things waiting to happen. One summer day, I rode my Stingray alone, through the scrub-covered back country, out where our stucco-box sprawl lapped at the wild edge of canyon country. And stumbled on the remains of somebody’s secret hideout, a trash-strewn lair camouflaged on all sides by a thicket of wild grass, high as my sixth-grade eyebrows.”

I was reminded of the bike flying scene in E.T. where the boys stare in amazement as they soar above their neighborhood into another realm. Although the tone of his essay is self-consciously noir, I couldn’t help but pick up notes of innocence, which put me in mind of the classic film.

The final essay of the collection, Cortex Envy, gives us a view into some of the psychodynamic dramas that helped shape the writer. Dery can be ferocious in taking down his ideological opponents and defending himself against his critics. With this essay, we get a bit of the backstory behind the ace argument maker. Is it a blessing or a curse, or is it both, I wonder, to grow up, locked in battle, forever defending your emerging self? Why do the words to the song A Boy Named Sue suddenly fill my ears?

To quote Jim Morrison, “Critical essays are where it’s at.” To be sure, thoughtful, well-written, long-form essays such as these are hard to beat." - Kate Walker

Mark Dery, The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink, Grove Press, 1999.

Mark Dery, The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink, Grove Press, 1999."Downstairs from New York's offices, there's a surveillance boutique that captures passing pedestrians on video camera. It doesn't bother any of us particularly. But author Mark Dery makes note of such things, and they upset him very much. In The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium - a scholarly text that reads less like cultural-crit than like a medieval apocalyptic screed - Dery posits that the "insanitarium" we live in could blow at any moment, and it would be our fault for abiding a culture in which we live to watch others and to make others watch us. But what obsesses Dery most are nightmarish aberrations like the Republic of Cuervo Gold, the town of Celebration, the profession of trend-spotting, and the bestial Jim Carrey, who "returns us to that glorious moment when naked apes emoted with their hindquarters." - Vanessa Grigoriadis

"Like many essays on pop culture of contemporary America, Dery's collection is an everything-including-the-kitchen-sink view of the end of the millenium (including comparisons of the Warren Report to Finnegan's Wake, and the author's fascination with the Edvard Munch painting The Scream). Occasionally, Dery's ruminations on our Nike-obsessed, Jim Carrey-imitating, X-Files-paranoid culture are hilarious; at other times, they definitely are not. But his point is well taken, that as we approach the next century, the U.S. is more of a culturally aware, and thus more culturally consuming, country than ever before. The author's previous take on cyberspace, Escape Velocity, seeps in here as well: the information age pushes the bits and pieces of pop culture further in our faces every day. The title is an old term used to promote New York's Coney Island amusement park, and a more appropriate monicker for 1990s culture can't be found. With no war to distract us as in previous decades, the culture itself has become a focal point for societal anxiety, and Dery's insights into the whys of this upheaval are most illuminating." - Joe Collins

"Centering his critique of the contemporary pop cultural landscape around the title image, borrowed from a sobriquet once applied to Coney Island, Dery sees "a giddy whirl of euphoric horror where cartoon and nightmare melt into one." He can be an astute observer of trends, adept at connecting seemingly disparate phenomena. The best essays here focus on our obsessions with conspiracy and paranoia, the new grotesque aesthetic in the arts and the changing dynamics of technophilia and technophobia in the new computer age. Unfortunately, the book is padded with writing on minor topics. Dery shifts focus rather too quickly‘one has the sense that he is throwing ideas at a wall ostensibly to see what sticks, but really hoping to distract attention from the results through the speed of his performance. And, too often, he filters his subject matter through suppositions plucked from high theory without examining the ideas he's borrowing, perhaps least successfully in his deployment of Georges Bataille to unravel the cultural import of Jim Carrey. Some inconsistencies stick out: at one point, he characterizes deconstruction as a "vogue," barely above the level of a conspiracy theory; at another, he concludes his analysis of freaks as culturally "other" with one of the hoariest of deconstructionist chestnuts, the condemnation of binary oppositions. Such jargon limits his writing, and makes the book feel dated, as his reliance on interpretive strategies left over from the '70s (particularly from French thought: Kristeva's abject, Baudrillard's postmodern, Deleuze and Guattari's schizophrenic) is stale even by the standards of academe." - Publisher's Weekly

"His usual style is to amass a clever bricolage of facts, figures, and relevant quotes, weave them expertly together, then wrap up with, at best, an original thought or two. Dery is most noticeable in the slightly shopworn theme that draws the essays together: "the pyrotechnic insanitarium of '90s America, a giddy whirl of euphoric horror where cartoon and nightmare melt into one.'' Dery does have an agenda (a rather doctrinaire blend of post-Marxism and post-New-Leftism)'if only he had an angle. He is an intelligent observer and has read and watched widely. His first essay, comparing our millennial situation to the massive social changes inaugurated and furthered by the opening Coney Island (the century's original 'pyrotechnic insanitarium'), is probably his most successful, perhaps because he is able to transcend mere clever collage. As firework shows go... a few sparklers and lots of duds." - Kirkus Reviews

"Flipping through anthologies of what are dubiously labelled The 'Best American Essays' is a bit like drinking luke warm milky tea with too much sugar. Except for the time Susan Sontag edited a volume in this series, they have always struck me as examples of the American essay in its most diluted form. If you want a good strong mug of Joe to hyper-caffeinate the mind, you have to go to American essayists who don't serve up that special blend of mediocrity and manners brewed up by those tepid 'Best American' anthologies.

High on my list of literary heart starters is Mark Dery, well known to Nettime readers from his contributions to 21C, and for his previous book Escape Velocity. In that one, he picked over all varieties of cyberhype, technoboosting and info flim flam. In his new collection, The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium, the whole of American culture goes into the Dery trash compactor. "All over the world, America stands for fun and death: Disneyland and the death penalty, Big Macs and murder.

Surely its significant that, as of 1992, America's two top export items were military hardware and 'entertainment products', in that order", Dery writes. Not to mention Stealth bombers and sneaking blow jobs in the Oval office.

Dery approaches America's "cultural landfill", from trashy movies to cult comic books, as a "a zero-tolerance critic of the growing encroachment of corporate influence on our everyday lives". There's always something a bit untimely about Dery. In conversation, he is the only man alive to have mastered hypertext in spoken form. And yet his language cojoins 18th century arcana with 21st century sound bites. He describes Insanitarium as "an obsolete hunk of dead-tree hardware that went to sleep and dreamed it was a Web page." The "no fly zone" between high and low culture is where Dery performs his textual aerobatics. He covers a lot of territory, connecting the most unlikely points in an American landscape, the contours of which he hugs instinctively.

What emerges is an America were the Unabomber is the Log Lady's dysfunctional cousin, and a maker of "exploding Joseph Cornell boxes". Where Oklahoma city bomber Timmothy McVeigh's conspiracy theories "read like an X-Files script written by Thomas Pynchon." Where the obsessives who mine the Warren Commission Report on the Kennedy assassination are America's home grown deconstructionists, and where the 26 volume report is "the Finnegan's Wake of paranoid America."

Dery does what 'postmodern' essayists used to do best. He folds irony over on itself. He makes irony ironic. By folding the layers of prejudice and distinction and discrimination that constitute 'taste' against each other, he produces moments of distance and clarity, within which the writer can reveal the connections between his - and our - little corner of the cultural themepark and the rest of the world. Irony might not be much of a tool against the "oozing insinuation of the mass media, blob-like, into every corner of the public arena." But then, who you gonna call? "Irony is a leaky prophylactic against consumerism, conformity and other social diseases" but its all we've got to stop us being "sucked, Poltergeist-like, into the vast wasteland on the other side of the screen."There's a strong moralist streak to Dery, but it isn't the "pathological puritanism" of the right wing pundits. The repression and denial of the dark and sticky side of life is for Dery part of the problem. "Always, the beast is closer than we know". A classic Dery technique is to start from whatever tepid-tea essayists find distasteful and sink his teeth into it.

He's good on any kind of freak or boundary crosser, like the kind who appear on talk shows, and give talk shows their bad name among the literary jigglers and danglers. "Daytime talkshows are equal parts geek show, peep show and Gong Show, made morally palatable by a gooey icing of psycho-babble. The deeper questions are: What is the chattering class really saying when it reviles these programs as 'freak shows'? Who decides who's a freak? And why are freaks so threatening?"This is the Achemedian point to which only irony can lever us - the point where there is not just a consideration of what is good taste and what is bad taste, but a questioning of who gets to make the distinction. In the knee-jerking hatred of talkshows among the chattering classes, Dery finds a "paroxysm of class revulsion". Trailer trash, welfare moms, and above all black people are to be discriminated against in the most polite way possible, by discriminating against their cultural tastes.

The trouble with taste is that the distinctions on which the 'cultured' middle classes built their respectable prejudice are coming unglued. Nobody seems to know what's high or low -- everything feels so slippy. It gets harder and hard to strain out the impurities. The result is a constant anxiety about separation. "The Brita filter is our fallout shelter, the existential personal flotation device of the nervous nineties." Everybody knows that the wealth of what's left of the middle class rests on a mountain of industrial waste, and that kitsch is as omnipresent as airborne contaminants, but nobody wants to admit it.

"If there's a message here, it's that we're going to have to make our peace with the repressed, whether its the body and all it implies (defecation, sex, disease, old age, and death) or the solid waste and toxic runoff of consumer culture and industrial production." Or in short, "it's high time we grew up, already."

Growing up, for Dery, is ending middle class denial, accepting the fact of the trash pile on which class privilege rests, studying the landfill for clues as to the process by which the turbulent, chaotic surfaces of consumer culture spew forth from the industrial world. Dery is one of those rare writers with a deep enough insight into the American soul, with an eloquence in all its stuttering dialects, to look America in its dark and gazeless eye, and not blink." - McKenzie Wark

"Like any good cultural critic, Mark Dery knows how to work a metaphor. The title of his newest collection of essays, The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink, refers to Coney Island at the end of the 19th century and its vertiginous blend of wonder and horror--from the light shows to the freak shows. Coney Island, Dery suggests, was a delirious spectacle that spoke to a nervousness about the 20th-century to come, and the author sees today's fractured electronic media reflecting our own anxieties in the same dizzying way.

Insanitarium traces the vapor trails of a number of cultural phenomena: the media reaction to the cloning of a sheep; the cultish cell of Nike employees who call themselves EKINs; the Disney-planned city of Celebration, Fla. Dery, who explored fringe computer culture in his previous book Escape Velocity, is at his best when he zooms in on the previously unexplored facets of his stories. Discussing how the media treated the Heaven's Gate mass suicide as "an object lesson in the evils of spending too much time on-line," he notes that the cult's cyber-outreach efforts actually stirred up a fierce backlash. A proselytizing mass newsgroup posting gained them a few converts, but the "ridicule, or hostility, or both" that characterized the vast majority of responses was strong enough to convince Heaven's Gate to leave this planet.

At points in the book, Dery lays the primary blame for our angst on what he dubs "the Gilded Age, version 2.0" -a second era when the delusions and delights of the moneyed few drown out the voices of the impoverished. In doing so, he places himself in the company of other old-school dissenters such as Noam Chomsky and Lewis Lapham, and the perennially angry political journal The Baffler, who focus on material matters of oppression while avoiding the Balkanization of modern multicultural scholarship. Unfortunately, Dery seems ill-prepared to contribute to these dialogues: His essays linger too long on points, such as America's precipitous income disparity, or the retreat of the global elite from civic engagement, that have already been treated at length in the lefty media.

What's more of a disappointment is Dery's dispassionate take on his subject matter. He roots his analysis in the more tragic consequences of the wrecking ball of global capitalism--dropping wages, vanishing job security, and mass firings--but loses that sense of humanity once he enters the rarefied strata of lit crit and media deconstruction. His distanced essays compare poorly to, say, those of The Baffler: At least that journal's best arguments build upon a core of steely outrage; they're less like ambling discourses and more like battle cries. (Tellingly, one of the most common criticisms of The Baffler, and other brash leftist polemicists like Michael Moore, is that they lack authority to speak compassionately for the swelling ranks of the working poor--as if that were the jurisdiction of who, exactly? CNN? Forbes Magazine?)

To be fair, Dery has succeeded in writing a suitable primer for reading the media at the fin de millennium, a respectable goal in itself. But that doesn't change the fact that we need less writing that showcases erudition while masking more immediate, ground-level concerns. What we need is for capable and perceptive writers like Mark Dery to put their hearts into their work: to write as if it actually mattered, and not just to turn the last tooth in the gears of a grad-school education." - Francis Hwang

"One of the main characters in William Gibson's cyberpunk novel Idoru displays `a peculiar knack with data-collection architectures, and a medically documented concentration-deficit that he could toggle, under certain conditions, into a state of pathological hyperfocus. This made him... an extremely good researcher'. This also serves as a pretty fair description of Mark Dery's career, as one of our pre-eminent info-node sifters - rhizomatic, haphazard and intuitive.

The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium is Dery's latest stage-dive into what he once termed `the intellectual moshpit'. With his last two books, the edited collection Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture and the indispensable Escape Velocity, Dery planted his flag on this field as one of its most passionate commentators and eagle-eyed critics. Not one to turn the other cheek, Dery's over-heated word-processor has ensured that most on-the-pulse magazines and journals around the world have at least one of his spirited defences or surgical strikes within its pages. This latest book is a collection of essays which previously appeared in embryonic form in such periodicals as Suck, 21.C, World Art, New York Times Magazine and Village Voice, threaded together via the metaphorical title--a turn-of-the-century description of Coney Island.

Considering the diversity of his subject matter - corporate logo-centrism, the Disneyfication of community, the Unabomber, Jerry Springer, Moby Dick, Heaven's Gate, bio-technology, formaldehyde photography, eugenics, etc. - Dery does an impressive job in sculpting a coherent vision of millennial America as an `infernal carnival' perched on a `fault zone'. In many ways a darker sequel to Escape Velocity, which has become the definitive guide to the wired world, The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium is itself a rollercoaster ride through a lurid landscape fairly pulsing with schizodistractions and apocalyptic contraptions.

Indeed Dery seems to relish his self-cast role as Calibanish carnival barker, hailing us to observe the freakshow that is the millennial USA and shudder at its gallery of grotesques. Of course Dery is too self-reflexive to labour the metaphor, and his focus on titillating topics often pulls back in order to expose the complex economic, historical and cultural forces which frame the important questions he is posing the reader. `Either/or questions for a both/and world,' as he puts it. Something like a hipper version of our own Stuart Littlemore, Dery is another persistent watchdog snapping at the heels of the Four Postmen of the Apocalypse: the military-industrial complex, the media, market fundamentalism and plain old ignorance. Like Mr Littlemore's, Dery's opinionated wit can be interpreted as an infuriating smugness by his detractors, or a spirited `touche' by his supporters.

After a preface on the grey zone between conspiracy theories and corporate practice, the book kicks off with an amusing, meditation on the ubiquity of Munch's The Scream as a meme infecting everything from key-rings to blow-up dolls. This is then followed by a long overdue essay on the significance of Clownaphobia, the creeping social suspicion that all clowns are psychopaths. The most compelling chapter, however, exposes the subterranean discursive affinities between the Unabomber's Wild Nature, and the digerati's Wired Nature. The individualistic intersection between this neo-Luddite's nostalgia and the futurist utopia valorised by Wired magazine is offered as the uncanny hinge on which a creaky country depends.

In the introduction, Dery urges us to consider his new offering as a `Gutenbergian artifact that rewards nonlinear reading and welcomes readers at ease with mental hyperlinks--far-flung associative leaps of logic... The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium is an obsolete hunk of dead-tree hardware that went to sleep and dreamed it was a Web page'. The author's commentary reads like a slick guided tour through an encyclopedia of postmodern references. One unfortunate side-effect of this quality is that it invites the reader to fill in the gaps, based around the formula, `how can you talk about x without mentioning y?' Editorial constraints aside, Dery occasionally makes some frustrating omissions which I would attribute to judicious restraint if it weren't for more obvious name-checks elsewhere. For instance, how could he resist the sanity-warping image of a line of ping-pong-ball sucking clowns in a chapter on this very phenomenon? Especially when such creepy head-shots morph into Munch's scream in the collective imagination (or at least mine). And how can he neglect to mention Mr Methane as a modern-day incarnation of my near-namesake, Le Petomane, who enthralled the crown-heads of Europe with his anal antics? Other figures haunt the margins of the text: the death-row prisoner who ended up as scanned slices of meat on the Internet, Jocelyn Wildenstein, the plastic surgery addict, Kinko the Klown, Westworld's malfunctioning androids, and the horse-penis-transplant in Sex and Zen all cry out to be acknowledged and catalogued.

Another criticism concerns the carnivalesque strain of his study, which in some ways makes the book read like a prequel to Escape Velocity. (`Serial killers?!' sneered one friend. `Soooooooooo early 90s.') The reason that such a cutting-edge critic would risk his reputation by re-treading the cattle-trail left by a herd of stampeding Damien Hirstophiles analysts, or mentioning the meta-arcane practice of body-piercing, is two-fold. First, Dery can never resist having the last word, and secondly, this accelerated hyperculture of ours is far more sluggish than we like to believe. Just when you think Goths have crawled away to die in a corner, or trade their lace for `distressed nylon', along comes Marilyn Manson. Consider the retro-lounge craze which, while waning, seems to have lasted longer than the decade it was imitating. Similarly, that pesky capitalist exploitation never seems to go out of fashion.

Leaping between so-called `high' and `low' culture like Frogger on fast mode, Dery wears his pinko-liberal stripes proudly on his sleeve, pulling out Hobsbawm, Marx and Chomsky, amongst others, to bolster his argument against the statistical horrors of the New World Disorder. He depicts the postnational global economy as the tightening vice of a self-described technological elite on the hearts, minds and stomachs of the downsized and disenfranchised. While this may be an interrogation of antidemocratic forces, one can't help feeling that Dery's `indignant-cop/cheeky-cop' routine lets the suspect walk free. Finding hope in `cathartically deconstructive' insights and practices of certain social counter-currents is--as Dery practically admits - almost a default optimism (although I acknowledge it seems a tad harsh to blame someone for not being able to pin the crime on a system which has walked free till now). Dismissing post-modem irony as `passive resistance' also seems like a light sentence considering it is so often complicit with the consumerist mentalities he is attacking.

After ooohing and aaahing at Dery's linguistic pyrotechnics, one craves a closer reading (preferably containing at least one sentence without an adjective). It takes more than thumbnail sketches to roast the ideological beasts that he has so expertly skinned. Having said that, however, much of the pleasure of this book is provided by the throwaway one-liners: `The Brita [water] filter is our fallout shelter, the existential personal flotation device of the nervous nineties.' `Hitler might have had a hard time on Usenet.' And my favourite, `Jim Carrey is Georges Bataille's Solar Anus, with a change of underwear'.Two more minor quibbles, since we're discussing Bataille, one of them personal and the other less so. Dery twice uses the phrase `excremental philosopher', and also `excremental fantasy' - a bit rich from someone who recently took me to task for using the term, `excremental nihilism' because it `didn't really mean anything'. In a different chapter, while discussing the gross-out strategies of cadaver-art, he also makes the claim that `French philosophy... tilts toward the formal, the theoretical, the cerebral; it has no idea what to do with a pig sawed in two'. This after an extended section on Bataille as an authority on abject, animalistic excess; someone who was, after all, a French philosopher. When Dery occasionally makes these binary statements, however, they appear more the products of convenience than conviction.

Indeed it was Bataille who once said something like, `I am only interested in books to which the author has been driven'. The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium certainly satisfies on this account, and is a passionate wrap-up of a decade still shaky with Pre-Millennial Tension. While an index would not go astray, and the statistics are occasionally inconsistent (is it 8.4 million or 3 million Americans who live in gated communities?) the strengths of this book are self-evident to those familiar with his talent for exposing the ideological irritant within the rhetorical engines of the rich and powerful. The horrific shapes which contort wildly in Dery's funhouse of mirrors are a fascinating backdrop to his `perilous tapdance in the minefield between pop intellectualism and academic criticism'. Dery combines the esoteric and the ethical, the entertaining and the emphatic, in a valuable catalogue which we can only hope will continue to guide us through the circus of everyday life." - Dominic Pettman

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.