"Sparks's debut story collection swirls with a Tim Burton-like whimsy. Ghosts nurse babies ("As They Always Are"), Death visits Earth as a New England prep ("Death and the People"), people evolve from trees (in the title story), and a girl, born in the land of the dead, is sent to Earth accompanied by a protective group of ghosts ("The Ghosts Eat More Air"). "You Will Be the Living Equation" describes a teenager's attempts to cope with a friend's suicide. This is much-traveled ground, but the story's poignant insights are enlivened by the element of the supernatural and a second-person narration. The collection's 30 stories, most no longer than three pages, are modern fables in which epiphanies replace moral lessons and tales unfold with Grimm-like wickedness. While the book's shorter, more fantastic pieces are often little more than exercises in imagination, they provide an unnerving atmosphere in which the longer stories can languish and offer the primal enjoyment of not knowing what will happen next. As this energetic collection shows, Sparks isn't afraid to take chances." - Publishers Weekly

As its title suggests, May We Shed These Human Bodies (Curbside Splendor) by Amber Sparks is a collection of stories that is grounded in reality, but often has a hint of the surreal, the supernatural, woven into its fabric. The power in these stories comes from the awareness that a life is at a tipping point, and the assignment of emotional weight to everyday events we typically ignore. Just out of sight, behind the curtain, in the shadows, strange things are happening—dark moments that echo our secrets and lies.

Many of the stories utilize lists and numbers to condense great yawning chasms of time, place, and horror into compact observations that leave us dented and eager for repair. Take this passage from “The Chemistry of Objects,” which elevates a common canister to sinister and far-reaching proportions:

“Exhibit 5WW: Metal Canister. Discovered at Majdanek, 1944.

The casual observer may, at first glance, mistake the canister behind the glass for a dented coffee can. The label is almost entirely gone, the faded gold paper clinging in shreds to the flaking, rusted metal. But if the visitor looks closely at the largest shred they may make out a group of small black letters, gone indigo with age and sun. Giftgas! the letters shout. How funny it sounds, like a children’s party favor. How exciting! A handful of bright plastic packets. Laughing gas tied off with curled satin ribbons.

But the letters do not shout in English, and the contents of the canister were never meant to be merry. The word is German. The English translation: poison gas. This can is not a coffee can, and it has never contained beans or laughing gas or party favors; it has instead poured pellets of gas into sealed chambers through special vents, smothering those inside. Polish Jews who’d never seen the sea, drowned in their own blood.”

What Amber Sparks does so well here is conjure up a memory of genocide by merely staring at a canister in a display case. To one person the meaning and graphics are merely an amusement, a bit of history, one moment in a sea of other moments. But to many others this object is horrific, emblematic of a greater evil in the world, one that cut a wide swath of destruction. And this is how she pulls us in and tears us apart—by using history, mythology, magic and the unknown to tell us her fables and dark truths.

In one of my favorite stories in the collection, “The World After This One,” Sparks tells us the story of two very different sisters. Esther is the reliable one, the conservative and worrisome sister, while Ellie is the wandering beauty, lost in her thoughts, lost in the world, connecting in whatever ways she can. This touching story about family is accurate in its depiction of how siblings relate. One day you’re defending your sister, saving her from the wretched grip of a dark and violent world, and the next day you’re dispensing judgment yourself—questioning her actions, yelling at her for being irresponsible and aloof. Take this moment from early in the story:

“Once, when Esther was in college, she told her father she was going on a Youth Ministry camping trip. Instead she drove the three hours to the city, picked up Ellie and took her to the shore for a week.

Ellie grew obsessed with the slot machines. On the beach, she gave her room number to several strange men. Esther had to keep answering the door in the middle of the night and explaining to seedy men with goatees that her sister wasn’t well.

Why would you want to sleep with all those people? Esther had asked her sister, exasperated and sad. Ellie had smiled. In just two days of sun her hair had gone nearly white and a big chunk of it fell over her eye, making her look like a sunburned Veronica Lake.

I’m allowing them to become gods, she had explained helpfully. Esther has not taken her anywhere since.”

There is a gentle and gracious wisdom in the words of Ellie, even if she is naïve and a victim in the making. It’s unclear which is worse—taking these chances that are sure to lead to trouble, or separating yourself from the world so that you can never get hurt?

There are insights in these stories, moments where Sparks sheds light on a wide range of emotional truths, leaving us nodding our heads, searching for breath, trying to quiet our beating hearts. In “You Will Be the Living Equation” we touch on the subject of loss and pain and the kinds of people that approach us in our grief. The first kind sympathizes and offers up their own memories of grief. This is the second:

“The second kind will sit with you in silence. They will have nothing to say, because they will understand that pain is not something that can be shared or solved, that pain is not a checklist or a questionnaire. They will understand that pain is not only loss, is not only sad, is not only one thing and not sometimes another thing altogether. That pain is not quantitative, but that it can be marked off with chalk lines on a cell wall just the same. That pain is not a landscape, and yet we carefully map its roads, its quick peaks, its long dips and even the smudges on the page that obscure intention or effect. That pain is not psychic, but that it does sometimes offer a moment of brief, bright clarity.”

And isn’t that so true? This is such a concise and brilliant observation. And whether Sparks it talking about loss and grief, or the way that a child’s hand tucked inside your own can fill your heart with peace and love—we are constantly rewarded with moments of depth, and consideration for our own frenetic lives.

I’m always drawn to the darker aspects of life, because I find it interesting to see how people deal with conflict and chaos, how characters reveal their true nature in these accelerated moments of anxiety and despair. Amber Sparks is not afraid to step into the darkness and paint bleak portraits of consequence and pain. Take this passage from “When the Weather Changes You”:

“You have them, she said, her voice surprisingly deep and strong. You have them in your heart, too. Just like me. Her face was purple and mottled, and her mouth collapsed into itself like a rotten fruit.

hat, Gramama, I asked, trying not to get too close. The sour smell of death was in the bedclothes. What do I have in my heart?

Ashes, she said. Your heart is full of ashes.”

And this:

“After a while, it became common to see strange snow angels here and there. Dead children splayed in dreadful poses, wingless and blue and covered in ice. The crows would circle in frustration, bewildered by the slow rate of decomposition and decay, unable to peck at the eyeballs hard as glass.”First, this is a horrible thing to say to your great-granddaughter—unless of course, it’s true. Then it’s something of a gift, isn’t it? But the second paragraph, the crows pecking at the frozen eyes of the fallen children, it’s a powerful image, haunting and disturbing, stealing a moment from our childhood, these snow angels, and turning them into angels of death.

In this powerful debut collection of short stories, May We Shed These Human Bodies, Amber Sparks has written a surreal love letter to our past histories—placed a message in a bottle and dropped into a raging sea, so that our future loves may hear what we have to say. Maybe these notes will declare our steadfast loyalties and maybe they will be riddled with dark threats and doomsday predictions. Either way, they will certainly not be meek. - Richard Thomas

“Death and the People,” the opening story in Amber Sparks’s new collection May We Shed These Human Bodies, ably sets the tone for the book that it follows. A group of bored mortals encounter Death and, en masse, set out for the afterlife. They spend their days there in a listless approximation of their terrestrial lives, occasionally frustrating the celestial agents around them; they watch as Earth proceeds through eons of change, struck by its relative emptiness, its majesty, its lush desolation.

Sparks’s work is irreverent yet carries with it an epic scope. And it doesn’t hurt that she knows how to get the reader’s attention — “Death and the People” becomes a sort of circuitous creation myth, albeit one where frustrated deities and video game consoles play a role.

In these stories, Amber Sparks hits the sweet spot between cosmic and irreverence, between comic and philosophical. The title story, in which a group of former trees laments their newfound humanity, elucidates a number of familiar bodies and states, yet makes them seem dynamic. It doesn’t hurt that Sparks uses the first person plural very effectively — rendering a sense of community that’s both all-encompassing and yet somehow alien.

When you think you have the book figured out — when you come to a work featuring an aging Paul Bunyan, say, which seems almost emblematic of a particular school of slipstream writing — you then proceed to “The Effect of All That Light Upon You,” with its (literally) visceral imagery. In it, bodies are reshaped, and minds are pushed towards an uncertain place between madness and transcendence. The counterfactual family history of “When The Weather Changes You” also impresses, as does the endlessly rewritten logic of “The Ghosts Eat More Air.”

The last word of this collection’s title gives a hint as to why it stands out among a number of its reality-bending compatriots. Sparks has intelligence aplenty on display, a talent for humor, and the ability to blend mythical resonances with contemporary anxieties. But her fiction is also rooted in the tactile and the physical, and it’s that quality that makes these works truly haunting. - Tobias Carroll

Fitting almost 30 stories into fewer than 150 pages, Amber Sparks packs her debut short story collection full of surprises. It’s tempting to call these stories fables, not just because of their length but because of the author’s simple, lyrical writing style and often fantastic subjects. But the collection is as wildly diverse as it is imaginative, with Sparks touching on domestic tableaus and the fallout of violence as frequently as she does magic bathtubs, feral children and new myths for the origin of Earth and its people. Short as these stories are, it can be tiring to read them all in one sitting. Fortunately, her range of subjects and unique take on each narrative make them strong enough to stand on their own.

The real challenge of the short-short form is fleshing out the characters. Sparks’s vivid details always leave an impression, such as a daughter pursued by ghosts her whole life, some leaving a “long narrow burn mark” on her arm as they skid past her skin. But that girl and many of the other characters in Bodies are often archetypes—sometimes nameless ones: the father, the baby, the hero. When Sparks finds more mythical motivations for their actions and dispositions, such as the isolated family cursed by a great-grandmother who leaves their hearts “full of ashes,” they feel even harder to relate to. That’s when the stories blur together. But at their best, Sparks’s shorts take just a couple of pages to push your imagination to consider the unseen, otherworldly ways our planet might work. In exploring everything from small family dramas to the supernatural, she makes all of it feel possible. - Jason Crock

May We Shed These Human Bodies. What is it? A collection of shorts and short-shorts. At times, a series of lists: objects in an exhibit, school periods and corresponding homework, numbering/bullet points (which turns Sparks' shorts into short-shorts), character types (Mother, Father, Child, etc.), math equations, and boxing rounds. An entry into all points of view: first, second, third. Longer stories that are plot-driven, short-shorts that are exercises in descriptive language or pondering theories. Bonus: the effect of varied forms is varied experience for the reader.

May we shed these human bodies: what does this polite request mean? Amber Sparks suggests shedding the human body is a means of ridding oneself of the possibility of being lonely or waiting for another body to comfort you. Dare I argue that every single story in Sparks' collection uses the word lonely or alone? She writes, "Dream of throwing a blanket over your lonely life at last." She writes, "You would always be the strongest, and you would always, always be alone." She writes, "It will leave you utterly alone." This device holds the collection together, although I can't help but wish for more varied human emotions. I became exhausted by loneliness, wishing I could tape together the pages, merge the worlds of multiple stories, thus giving each character a friend. Nor was I fully comfortable with these characters whose only mobility is down (sometimes literally down the drain).

Her varied form comes with varied tone. "As They Always Are" presents a mother with a baby whose appetite is vicious, though his mother is too sweet to care.When she dies, he never eats again, though he grows chubbier. How does he thrive? Why, the ghost of his mother feeds him at night, which we know only because his new stepmother is caught spying from behind the crib by the baby's ghost mom, which kills him (for some reason). The next morning, "when the sun rose, the baby's nursemaid came to check on him as she did every morning. She found him lying on his back, eyes open and quite dead. All the fatness and pinkness had gone from him: he looked as though he'd starved to death."

While her fabulist tone is the cleanest, Sparks dips into the voice of trees, teenagers (complete with video games and dudes and phrases like "what the shit..."), ghosts, dictators, a city, poets, and children. If you're not sure what you like, it's not hard to find something to like; there are so many options in Sparks' collection that something will strike even the pickiest of readers.—Melanie Page

Amber Sparks has a knack for saying a lot with very little. The short stories in this collection range anywhere from a few paragraphs to a few pages long, and yet they tell their story more clearly and more entirely than some novels I have read.

This book popped up on my radar way before the review copies were available. And the wait was almost excruciating. Curbside Splendor teased us with the book cover, which is lovely, and shared blurbs by Amelia Gray, Ben Lorry, Michael Kimball, and Matt Bell, all of whom I've read and adored. That's always a good sign. And the title is just amazing, isn't it? May We Shed These Human Bodies. I envisioned people unzipping their skin, letting it fall off their shoulders and puddle down around their feet, as their robot-like inner spirits step out and shine like ghosts.

While I didn't find a story quite like that one in the collection (you have to admit, that would have been a cool one), I did discover a bunch of excellent tales about ghosts, of both the motherly and haunting kind; twisted spins on Peter Pan and Paul Bunyan; a nursing home full of cannibals; a city that longs to travel; trees that become humans; and a magical, mysterious bathtub.

The one I enjoyed the most happened to be the very first one that I read - Death and the People. It's the story of Death, who has come to Earth to collect a soul. But the people of Earth have grown tired of Death sneaking in and stealing the ones they love, one by one. So they stand their ground and bully Death into taking them all. It's a wily, cunning little tale that kick starts the collection and sets the bar incredibly high!

Amber weaves a wicked web with her words, saying what needs to be said without spending a lot of effort, trusting that her audience will have no choice but to be sucked in. And sucked in, I was. Her stories read swiftly, sting fiercely, and then retreat quickly to make room for the next. Each little world she creates breathes hard and fast and lingers with us long after we leave it behind.

I'd be very interested in seeing what she can do with a full length novel. - thenextbestbookblog.blogspot.com/

The first Amber Sparks story I read, or recall reading, was in NY Tyrant a couple years ago. “These are Broken, Funny Days” ends after about half a dozen paragraphs, before a full page has passed, but not without doubly surprising the reader. There’s the first surprise of Sparks’ excitedly strange, unpredictable plots (in this case the mystery of the speaker’s current situation) and the second surprise—that the story she captures rings so familiar and true. By the end of “These are Broken, Funny Days,” I found myself chuckling at the wonderfully precise complaint of the knife-wielding narrator: “Blood smells bad.” Because blood totally does.

Now, Amber Sparks has a book, May We Shed These Human Bodies, out this month from Curbside Splendor. It came as no third surprise that I found with each story a new shock, something unexpected. After the first sentence, there’s no telling where a Sparks story might take you, and there’s definitely no telling what that first sentence might be.

Sparks gives us the canon—from the initial story of Death as a kind bureaucrat dealing with overcrowding, to magical bathtubs and fairytales and heartbreak and sibling rivalry, May We Shed These Human Bodies does exactly what its title seeks, and leaves us surprised and unskinned, clutching our hearts. -Joseph Riippi

You wrote a book. And it’s a beautiful book. How’s it feel to hold it in your hands?

It feels wonderful! I mean, I’ll bet you remember that moment. I bet every writer remembers it forever. Ever since I was little, I’ve loved books and the idea of one of them being mine, with my name on it—it’s like a totem or something, it’s a magical feeling. And of course Curbside and Alban Fischer did such an amazing job with the book. It really is beautiful, isn’t it? I nearly passed out the first time I saw the design, it was so perfect.

One of the things I love about this collection is that, from story to story, your narrators change remarkably. It’s not the same voice every time. Like “To Make Us Whole” or “All The Imaginary People Are Better At Life” seem closer to what I imagine The Author’s Voice might be like. But then you carry us away into something much more magical and surreal—like “The City Outside Of Itself” or “Death And The People.” Is there a perspective from which you prefer to write, or that you find more exciting? What kind of story do you like to write?

I get bored easily, and so I don’t like to write from any one particular voice. Sometimes it’s more surreal, sometimes a normal human being. Often my narrators are sane but just barely, which is always very interesting to me—people living in that tipping point. I like to change it up a lot. Certainly the voice on stories like “All the Imaginary People” is closest to my own voice, and sometimes if it’s a more personal story, that’s the voice I really have to use. But for fairy tales, for fables, for larger tableaus, I prefer a third person omniscient, a god-like narrator. I think it gives the story a telescopic, mythic quality. I also use a lot of second person. Second person works nicely for me when I want to create a bit of distance between a very emotional subject and a very logical, cool narration. For instance, in “You Will Be the Living Equation,” the subject is a boyfriend’s suicide, but I wanted to look at the problem in an almost mathematical way, and I think that second person helps to facilitate that. Otherwise I’d have been stuck in the character’s own emotional mess.

Even in the shortest stories, characters can take long, transformative journeys, and that gives a fairy tale-ness to many of these stories. Feral children, monsters, bathtubs that spit out copy-versions of ourselves. (“If You Don’t Believe, They Go Away” stands out as a particular favorite). What is your own relation to fairy tales? Do you actively seek to engage with that medium in your writing?

Oh, absolutely, I do. When I was very small, my dad gave me a book that he’d had as a child, a book of fairy tales and tall tales, anything from Perrault to stories from Arabian Nights to Aesop to Johnny Appleseed. And I must have read it a thousand times. When I was a little older, my favorite book at the library was Hans Christian Anderson’s collection of fairy tales. I love the logical absurdity of fairy tales, as well as their almost natural cruelty. I would say that I have a very logically absurd mind, and I don’t know if this is why I was drawn to them, or if they shaped me, but the way I think dovetails very neatly with the way fairy stories are written. There are very specific formulas, and things have to happen a certain way, certain characters must do and say certain things – and yet within that tight framework you can make anything in the whole world happen. Anything your brain can summon. That’s something that I’ve always tried to write, and of course, examining that logical absurdity is the sort of meta conceit behind “If You Don’t Believe, They Go Away,” as well as “As They Always Are.”

In “The Poet In Convalescence,” you describe the “fingerprint” as “A map you make yourself, quadrant by quadrant, inch by inch…Here there be monsters.” How much of the book draws on the personal for you? Which of the stories would you say contains the most “Amber”?

Oh, well, probably all of the stories contain a lot of me. Unlike many writers, I tend not to write anything that’s very much like my real life, partially just because my real life is quite dull on paper. But my sensibilities, my personality, is all over these pages, fingerprints everywhere. If my book were a crime scene I’d be screwed. Most of my characters are an awful lot like me: neurotic, hypochondriacs, terrified of death, dreamers rather than doers, people who are generally on the outside looking in. I suppose that of all the stories in the book, the title story is the most personal, oddly – yes, the story about the trees that turn into people. Because I think if there’s one thing that I think about more than anything else, it’s the fact that I always feel like such a failure as a human being – and I feel like we all fail at being people. It explains why we destroy ourselves and fail other people so badly, too. I wrote that story to try and explain why maybe we all suck at being alive, when every other animal and plant and virus and living thing seems to be so good at it. Well, except for pandas. Pandas are evolution’s little joke, even more than we are.

I know you just had a launch party in Chicago for the book, and you’re coming to New York for the Franklin Park Reading Series this fall, which is always a wonderful evening. Any other readings/touring planned?

Yes, a ton of stuff! After Chicago I’ll be in Minneapolis and Ohio and Indianapolis, and then later this fall I’ll be in New York and Baltimore and DC and Providence and Atlanta and maybe Boston, too. I get freaked out just thinking about it! Oh, and there was a change in the Franklin Park thing – I’ll be there in January now, but I’ll be in New York for the Salon Series (with the awesome Paula Bomer!) in October. So much stuff. It’s up on my site, too, if anybody’s interested, at http://ambernoellesparks.com/readingsevents/.

Lastly, I hadn’t read “These are Broken, Funny Days” in awhile, but remembered it as I sat down to write about your book. Any reason you chose not to include it in the final?

Yes, which was really hard because it’s one of my favorite stories. But there are a bunch of stories that didn’t make the final cut because, while the book doesn’t have a theme per se, I found that it had a very hopeful, transcendent quality, even the very sad stories. Everyone felt like they were all trying so hard to be better people, to be better at life. And of course, the narrator of “These are Broken, Funny Days” is a serial killer who relishes what she does. So it just didn’t quite work anywhere in the collection. But I’m working on a second collection now, so who knows? Hopefully there will be room for it there. This next collection is a bit darker in tone, I can tell already. The humans are definitely failing.

The Desert Places

This pocket-sized edition of a hybrid text by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss explores the evolution of evil in worlds both seen and unseen and features full-color illustrations by Matt Kish, illustrator of the critically acclaimed Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page.

The Desert Places offers a beautiful history of evil. It is as dark and violent as you expect, but roughly ten thousand books published in the last year were dark and violent. This work is distinguished by its construction.

First, the collaborators (authors Robert Kloss and Amber Sparks and illustrator Matt Kish) use a variety of structures and schemes to develop their subject. The novel is partly a survey of nine periods of history, including the darkness of prehistory and a dystopian future which reads like a Terminator-movie flash-forward. Narrative sequences are sometimes told from the first and more often from the second person point of view. Other sections include an interview between the Alpha and the Omega. Chapters are separated by short, italicized sections titled [. . . An Incomplete History of What Passes for Evil . . .].

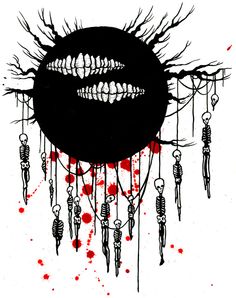

The most distinctive and beautiful pages belong to Kish’s illustrations of, among other things, skeletal sperm and a multi-mouthed orb-shaped monster. The style of art may remind readers of Pushead’s designs for old Metallica t-shirts. They are, first, morbidly attractive, but they more than accompany the text. Over the course of the book, that orb-shaped monster gains and loses and regains mouths; becomes increasingly linked with and physically joined to skeletons; and is briefly made to disappear in the midst of a city’s rise. But the monster returns again, and with more mouths than ever. Its variations underline one idea of history suggested in the prose: that men think they are civilizing evil out of their lives when they are, at best, covering it with concrete and government. That cover does not save men from extinction.

Both the variety and the visual appeal of the novel call to mind William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. In his poem, Blake reworks traditional definitions of heaven and hell and their citizens. Here, Kloss and Sparks begin with a glossary in which terms like “love” are redefined as an “unimaginable need . . . no matter how much skin you inhale, no matter how many bones you snap, you will never learn to satiate it.” The need is not just for violence but for continual newness. Murder begins with intense pleasure and devolves into boredom and exhaustion.

These writers rework tales as well as terms. In their creation story, paragraphs of questions make the “you” interestingly ambiguous. “Did you sell them the pleasures of your garden? And “Did you build the shape of man into the rocks to know the joy of murdering him?” splice together our ideas of God and the serpent. The sentences, when they come, only add to the mystery: “You must have plucked your ribs . . .” and “You must have said, ‘Father, make for me a friend so I may slay him.’” These lines suggest that the God-serpent is also, in part, a less-than-innocent Adam.

This “you” figure occasionally borrows names from now obsolete cultures, like Herne (pagan England) and World Encircler (ancient Egypt). He represents our urge to violence, but he often acts as a finisher. What humans begin, he ends. When the audience at the Roman Coliseum gets tired of standard gladiatorial combat, wild animals are added to the mix. Only later, the “you” enters to kill animals, fighters, and audience alike.

He shares the audience’s weariness. As the glossary has suggested, he thirsts–we all do–for new beginnings. Man’s apparent progress from prehistoric savage to rational thinker of science has given him some thrills, but they do not last. The “you” grows bored with Romans, inquisitors, and astronauts alike. He often becomes bored by himself and his urge. This becomes most evident at the novel’s end. Mankind is dying off after a nuclear war. It ought to be a great time for him, but the “you” kills “with sighs, with yawns.” The empty world looks as it did at the creation, a dusty rock where the “you” feeds on bugs and worms. He considers two possibilities. The first is to face the horror of himself and commit suicide. The second is to wait for the world to renew itself, again grow green with life and noisy with men, enabling him to resume his old ways. He considers them, but does nothing.

But the book’s greatest wonder may be that three artists—one illustrator and two writers—have put together a project so fluid and coherent. A collaborative novel faces at least three dangers: that the styles of its contributors will clash; that it will be too easy to discern the weaknesses of each contributor relative to others; or, on the other hand, that the strengths of each contributor will be diluted as a result of the team effort. Kish’s illustrations, as I have said, fit well. The prose works at all levels, down to the words and even the letters. Consider this gem: “Had you a mother, she would have smelled like this, of milk and dank and blood and mold.” The sounds of the four adjectives complement one another. The m’s, k’s, d’s, and l’s shift positions with the advance of the sentence, appearing and disappearing as we move from the familiar sweetness of mother’s milk to the wretchedness of mold. This sort of prose does not suggest clashes, weaknesses, or dilutions. It suggests a great unity of purpose and, moreover, achievement. - MARCUS PACTOR

Evil is ubiquitous. It’s in the best literature and (as I present it to my students) it is the reason why humanity needs literature: as relief from evil and as elucidation for evil. The Desert Places, the new hybrid text by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss, with illustrations by Matt Kish, depicts the history of malevolence from primordial Earth all the way into a nightmarish technological future. Plenty of other narratives have depicted the fall and subsequent struggle of Lucifer, Chamcha, Grendel, et al., but what sets Sparks’s and Kloss’s narrative apart is its broad scope within such a slim package.

There’s a belief that brevity does not afford a text enough emotional weight. This book challenges that notion. The Desert Places clocks in at just over eighty pages, yet the gravity of the subject matter is not lost. Sparks and Kloss depict their nameless protagonist (call it Evil, Belial, Death, Time, Satan, The Void, whatever) by choosing ten points in history as well as interspersed interruptions such as entries in “an incomplete history of what passes for evil” and a touching existential discussion between The Alpha and The Omega. This in addition to the unsettling drawings of Matt Kish, rendered in shades of pink and black, accentuate the disquieting subject matter.

Evil entities and antiheroes are fairly commonplace now, but Kloss and Sparks exceed expectations and expertly tap into the gravitas of their subject by using “you” to address The Beast, as when the personified curse of King Tut dances with a female archaeologist in Cairo:

You could murder her now, but sometimes it is hard to be alone with so many dead things. Sometimes you grow weary of death. And so you let your face slightly shift shape, grow longer and more human, while she purrs, just a little. And still you dance, a monster in fancy dress, foxtrotting thirty-five centuries out of time.

By using “you” throughout the text, the reader is placed in the position of timeless evil, and, briefly, feels the pain and weariness that comes alongside the position of Grim Reaper.In The Desert Places, Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss commiserate with darkness, and through this they dissect a core element of us all. People are drawn to narratives that feature the downtrodden because at some point everyone has felt cast aside, overlooked, and misunderstood. There is a dark, malformed core in us all. Kloss, Sparks, and Kish are just casting light upon it. - htmlgiant.com/reviews/the-desert-places/

Despite its brevity (86 pages), Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss’s The Desert Places should be mulled over slowly, deliberately, and preferably, if one is squeamish, in well-lit places, for this hybrid text of lyrical rhapsodies, interrogatives, lists, Q&As, omniscient pronouncements, lexicographic glossaries, lush vignettes, and gruesome full-color Matt Kish illustrations is an extended meditation on the nature of Evil and, through indirection, readers are left thinking of the nature of man.

The prose is powerful, striking, at times approaching the pitch of Melville and the King James Bible. Consider this account of Evil’s creation at the beginning of the world:

Who were you when the first breath of heaven burst forth? When all the light and matter and moments blazed from nothing? When fires scorched the firmament and all was shrouded in dust?… You were a negative, a dark absence, a clump of cells crying to come together. You were a pause in the flickering before consciousness. And when the atoms swirled, and when the skies yawned, and when a nervous god, still virgin to creation, called you forth: did you marvel at your luck?… Did you grab the stars by their throats? Did you wear the skins of dead galaxies, your eyes ablaze with impossible fury?.. Where were you when the collisions coalesced? When molten spheres blackened, flared, drifted and circled? What sounds did you know in the voice of the whirlwind?

Setting aside contemporary scientific references (cells, atoms, etc.), one can imagine this forming part of an ancient Mesopotamian text and becoming part of an animating mythology that might still resonate today.

But what do we learn of Evil?

Evil is relentless in its hunger for death and destruction, and unabashedly proud of the carnage always in its wake.

Here is the request Sparks and Kloss imagine Evil making immediately after its creation:

You must have said, ‘Father, make for me a friend so I may slay him.’

+

As strange as this might sound, one feels sorry for the one-dimensional Evil depicted in these pages. Its only pleasures in the death and destruction, yet “even a man’s death, no matter how dreadful, ceases to amuse, after a time. How well you know this already.”For all its sinister malice, the anthropomorphized Evil presented by Sparks and Kloss is essentially a flat character.

Recall if you will E.M. Forster’s discussion about “flat” versus “round” characters: “The test of a round character is whether it is capable of surprising in a convincing way. If it never surprises, it is flat.”

Evil will never be anything more than evil; it has no existence outside its conceit; Evil is flat; Evil never surprises.

Yet flat characters, like the straight man in a comedy duo, serve a purpose: to let its opposite shine, and in this collection, the vignettes most closely focused on human interactions are the ones that shine brightest.

Early on, Evil wakes to the “sound of the man in the garden” as he goes about naming “the animals and the creeping things.” Evil stands in soundless awe at this audaciously constructive and creative act.

[Man] named them with his godliness, with his upright posture, with his opposable thumbs…

… And then there was woman. And she was nothing special. But she was wide in places, and she was narrow in other places… And I waited. And now he set about naming her….

First, he named her “Mine.”

... He named the parts of the woman who lay before him, wide parts and narrow parts, pink part and white parts, soft parts and hard parts, dark parts inside that drew him like honey. He named her with his moans, with his brute thrusts. He named her with heavy breathing..

As Evil follows man around through the millennia, we sense envy. We sense a desire to be, well, more than its conceit.

It was good to be present at the birth of people. To understand how something so pink and frail survived the forest. How they learned to shape clay, to use stone tools, when the only implements I needed were those I was created with, the claws and the teeth, the merciless ravaging soul…

I watched them from the shadows, the rise of their glory. I watched them from the cold red shadows, shivering in my only-ness.

What evil lacks is the capacity for love: “The out-of-reach, the indescribable, the thing you were born without; and no matter how much skin you inhale, no matter how many bones you snap, you will never learn to satiate [your need for] it.”

Unlike Evil, which does not build but only devours and destroys, mankind has constructive capacities and seeks to make sense of its surroundings.

This is not to say that mankind is incapable of evil. Even the Enlightenment — “an age of mathematics and formula, of calculations and chemicals, of rhetoric and philosophy” — was “an age of murder and suspicion and terror, an age of bread riots and informants and double-dealings and bloody streets… A cold age of cadavers and cutthroats, of men evolved to something almost echoing you.”

The collection’s stand-out vignette takes us to Cairo of the 1920s, to a party celebrating the opening of Tutankhamen’s pyramid. Evil is “dancing something called a foxtrot” with a beautiful English archeologist. The desire that Evil feels for this lady is palpable in nearly every sensuous word.

Her dress is gold and her skin is gold and her hair is gold, bobbed short to show her long and lovely neck and naked back.

It is a warm and lovely night and there are too many stars to count, and your companion is graceful and sleek as a cat. Her ear is a seashell, pink and cool. I have eaten many priests of this land, you whisper into it. She smells of honeysuckle and roses and something muskier, too. It will be worth it to peel the flesh from those long white arms, to pop them like grapes and suck the buttery marrow. Your skin tightens around your bones and your arm tightens around her waist. You draw her closer. You breathe faster. You bring her chin up, breathe desire into her nostrils. The music changes, picks up pace, and you see the spinning chandeliers reflected in those dark eyes, the widening iris…

As close as Evil holds this woman, what he wants from her — something approaching love — is, for Evil, unattainable.

You could murder her now, but sometimes it is hard to be alone with so many dead things. Sometimes you grow weary of death.

+

Ben Marcus, who has rightly earned an exalted place in the firmament of contemporary experimental fiction, recently spoke about his like for bleak perspectives:In the end I am uplifted, profoundly so, by the bleakest, despairing work. It’s a great unburdening to read work of this sort. I do not want to be asked to pretend that everything is all right, that people are fundamentally happy, that life is perfectly fine, and that it is remotely ok that we are going to die, and soon, only to disappear into oblivion. I feel a kind of ridiculous joy when writing reveals the world, the way it feels to be in the world. That’s what hope is, a refusal to look away.

Make no mistake: The Desert Places is an unfailingly pessimistic book. A vignette set in some vaguely futuristic time period, begins thusly:

The girl in the trash receptacle is not really a girl. Not anymore. She’s a trail of destruction, the crumpled instructions on how to steal the life from a body. She is an eye, several fingers, a hand, a foot: a pile of teeth and hair and toenails. She is a heap of dead skin cells.

Implicit in this tight language is the fact that this girl was once much more than presented here — she once was alive.

Yes, we are doomed. We know that we will die. This is not, as Marcus says, “remotely ok,” but it is true.

Don’t flinch from this vision that Sparks and Kloss present. Yes, evil lurks around us, but in its periphery exists mankind, with its dueling capacities for good and evil, and with its capacity for love and beauty, innovation and invention — all of which are beyond the capacity of unalloyed evil.

Is that what hope is? Knowing that, as tarnished and imperfect, as doomed to death as we are, we are always more splendid as Evil? - Nick Kocz

You should drop everything you’re reading and pick up The Desert Places by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss and illustrated by Matt Kish. Brian K. Vaughan described his new graphic novel Saga as “Star Wars for perverts.” The Desert Places is the history of the world, not necessarily for perverts, but those who want to shed the artifice of detached objectivity and dive through the gory narrative of humanity and the violent poetry of blood and guts. I once called Amber Sparks the “fairy godmother of rebirth” that “transmogrifies the ordinary.” In this combined narrative, the Biblical intonations have a more ominous etiology and the ordinary becomes savagely truculent in a deconstructed tale of mankind. The Job-like inquiry that is at the center of one of the greatest Cosmic questions ever posed is flipped. “Did you build the shape of man into the rocks to know the joy of murdering him? Did you ferment the first soil with the bones and bodies of your construction? Did you stack the lands with death even before the first life? And in the hours until the first victim staggered forth from the seas, did you wander the crimson lands, peer into the halls of death and mourn the vacant corridors?”

Heroes and villains are absent even though the textual provocations are epic. The prose is lyrically bestial, crimes of harmonic diction by Sparks and Kloss channeled into elegiac carnage. Matt Kish’s illustrations are the disturbingly visceral guts that bind the book together, a chaotic nightmare of floating organs, deathly spheres, and skinless personas haunted by the skeletal visage of cruelty. They’re not for the meek of heart, but serve as a stark reminder of the butchery people have been inflicting on each other since, well, forever.

“And then there were no gods and there were no monsters. Then the worlds we have known together, worlds a thousand, thousand years ago, fell to ruin. Ever they stain my dreams. Ever they rise up before me, ever they will. Even now… those hands drip with bison blood, with berry juice, stirring something old in my bones and my blood, drawing the old lust and rage in me like a black storm.”

There is an interlude that involves an exchange between the Alpha and the Omega and despite the dark theme of much of the book, there is also satire and hope in the humor, albeit a morbid one. Both authors deftly handle religion, myth, and philosophy, juggling them, then ripping apart the old layers, constructing new cities on the corpses of dead ones. Unfortunately, the future holds little hope:

There is an interlude that involves an exchange between the Alpha and the Omega and despite the dark theme of much of the book, there is also satire and hope in the humor, albeit a morbid one. Both authors deftly handle religion, myth, and philosophy, juggling them, then ripping apart the old layers, constructing new cities on the corpses of dead ones. Unfortunately, the future holds little hope:“When the humans headed for the skies, we were briefly abandoned… And then we showed the humans what our new bodies could do, how fear could find them even in the galaxies beyond their own…We were careful butchers in space.”The book is short but powerful and will force you to wander the deserts of your own mind. It’ll force you from the Oasis you thought would provide succor, only to realize it was all an illusion. Read The Desert Places by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss right now because the illusion can’t last forever.

- Peter Tieryas

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.