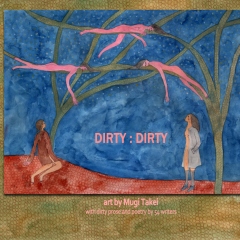

Dirty: Dirty: An illustrated anthology of 'dirty' writing. Authored by Debra Di Blasi. Illustrated by Mugi Takei, Jaded Ibis Press, 2013.

"It's pleasant being naked, as swimmer or writer or reader.... Naked's a way of being free, unencumbered by garment or censor. There exists no other way of knowing certain things, or oneself, without stripping away." - from the Preface by Debra Di Blasi, editor

One artist and 54 writers accepted the challenge of creatively defining "dirty" in the 21st Century. Mugi Takei's delicate, profane watercolors position the human body within, on and against nature. While some writers surrendered to play through sexually explicit love poetry, bawdy fiction, threesomes, twosomes, onesomes, and all the delightful fantasies and realities in-between, others suggested genocide to be the real dirt of humanity, or offer sexy, new versions of biblical stories. As an anthology, Dirty : Dirty exhibits the beauty, humor, raunch and invention possible when talented artists and writers tackle a very old subject.

THE ARTIST: Mugi Takei

THE WRITERS: Greg Bachar, Elizabeth Burns, Jennifer Calkins, Jane L. Carman, Kylee Cook, Beth Couture, Dirk Cowan, Justin Dobbs, Trevor Dodge, Rion Woolf, C. M. Connelly, April Gigliotti, Christopher Grimes, Steve Halle, Jeff Hansen, Michael Harold, Garrett Hayes, Jacqueline Heffron, Lily Hoang, Nabila Najwa, Eric Jeitner, Liesl Jobson, Steve Katz, Kimberly Koga, Stacey Levine, Marilyn Jaye Lewis, Robert Lopez, Cris Mazza, Joe Milazzo, Kathleen Miller, Scott Million, Theresa A. O'Donnell, Jordan Okumura, Melanie Page, Mitch Parker, Aimee Parkinson, Jack Rees, AE Reiff, Doug Rice, Thaddeus Rutkowski, Davis Schneiderman, Mikal Shapiro, Gary Shipley, Ascot Smith, Rob Stephenson, Helen Tran, Holms Troelstrup, J. A. Tyler, c.vance, Laura Vena, Hal Wert, Lane Williams, Alyssa Wisener, Lidia Yuknavitch

Writing sex is notoriously difficult and there is ample evidence, in critical discourse, of how writers fail to rise to meet the sexual occasion. In her 2009 essay "The Naked and the Conflicted," for the New York Times, critic Katie Roiphe lamented how contemporary writers, and men in particular, approach sex in their fiction. She states, "The younger writers are so self-conscious, so steeped in a certain kind of liberal education, that their characters can't condone even their own sexual impulses; they are, in short, too cool for sex." She prefers the brawnier and more explicit work of writers like Mailer, Bellow, and Updike, writers who "were interested in showing not just the triumphs of sexual conquest, but also its loneliness, its failures of connection."

Roiphe is certainly not alone in criticizing sex in contemporary literary fiction. Time and again, critics decry how literary fiction approaches sex. Only a few writers, such as James Salter or, perhaps, Mary Gaitskill are free from this critical glare. The problem of sex in fiction is so notorious that The Guardian offers, annually, The Bad Sex Award for Fiction. The gesture is somewhat tongue-in-cheek, but each year, you can peruse the "bad" excerpts and see that a great deal of literary sex is bad, indeed.

There are any number of reasons why writers struggle to write sex. For one, it is awkward. It's hard to know how to bring two (or more) characters into a situation where they will bare themselves intimately. Many writers try to bring the emotional and physical experience of sex to the page and many writers fail. It is often said that if you know how to have sex you know how to write about sex but such is not the case. Doing and writing, no matter the subject, are vastly different things.

There is also the matter of language. What words should writers use? In romance novels, which generally offer lavish sexual scenery, there are all kinds of swooning and euphemistic approaches to writing about sex. The scenes are explicit without being explicit. The scenes use language that doesn't exist in any reality so it's hard to feel a genuine connection to the sex being portrayed. This matter of language is a complicated one though because to use the clinical, more accurate terms is not especially sexy. The biological words for genitalia have an uncanny ability to disrupt any narrative just as much as the phrase "turgidrod"or "throbbing manhood."

In truth, sex is absurd as a physical act, so good writing about sex should find a way to convey that absurdity along with the intensity, the humor, the beauty and the ugliness of sex.

The new anthology Dirty: Dirty (2013), featuring art by Mugi Takei and "dirty writing" from fifty-four contributors, is a recent entry in the canon of sexual writing. The title is a curious one because it creates a set of expectations that aren't really met and therein likes what may be this anthology's biggest problem.

What works is the myriad of ways writers have interpreted the sexual. There is nothing literal or clichéd here. There is no rote prose and poetry about romantic interludes or sexual awakenings. Instead, the prose and poetry in Dirty : Dirty are short and sharp and offer a post-modern take on the ways we are intimate, what it means to be intimate. Much of the work features an explicit and anatomical focus on the body, stretched and splayed for sexual delectation or exploitation. Gary J. Shipley's "Scopophilia"—which means the pleasure derived from looking—pulls the reader into a bizarre scene: 'Through an open door I watch a party of fleshy metronomes. The puzzled detail of their faces belies the smooth, patterned order of their encounter. A vagina breaks free of its repeated union, pulsating grotesquely like a garroted throat." The imagery and the language are lovely, creating a scene that is magnetic and repulsive, like much of the work in the anthology. - Roxane Gay

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.