Anna Kostreva, Three Pathways to Get Anywhere (Except When There is a Dead End), Rough Beast, 2016.

excerpt

www.annakostreva.org/index.html

The independent press and literary project Rough Beast is pleased to announce its latest publication, Three Pathways to Get Anywhere (Except When There Is a Dead End), a work of experimental non-fiction by Berlin-based architect Anna Kostreva, edited in close collaboration with Joey Horan and designed by Studio YUKIKO.

The book is a constellation of essays, poems, impressions, and photos curated from the architect’s journals kept during her six weeks of travel through China, Japan, and Singapore in March and April of 2015. Kostreva’s sharply insightful text, as experimental as it is accessible, spreads itself across genres and themes. It integrates personal anecdotes, urban and architectural analysis, and musings on the foreign to examine what can and cannot inhabit global practices. With writing that takes both stylistic and thematic cues from the fragmentary writing of Renata Adler and Etel Adnan, Kostreva poses questions from a perspective where intercontinental travel has become normalized and societies on the opposite side of the globe increasingly appear in our imagination only as quantifiable sets of big data. Why do we still want to travel, and is it possible to escape the tropes of globalization?

Kostreva’s book presents an absorbing narrative through the mind and eyes of a young female architect interested equally in the state of modern cities as in their capacity to speak to those who visit, use, and live in them. Through its combination of subjective revelation and nuanced critique of global citizenship, her deeply probing and thought provoking writing reflects what art critic Peter Osborne describes as the ‘inherent hopefulness of travel’.

The publication – a complex dialogue between the text and images taken by the author of urban phenomena encountered along the way – is designed by the award-winning Berlin-based design studio YUKIKO, whose work with the magazine Flaneur has been distinguished with the D&AD Slice Award (2014) and, most recently, a nomination for the German Design Award (2016). Studio YUKIKO consists of Michelle Phillips and Johannes Conrad and has been active in Berlin since 2012. Their work includes clients in the arts, entertainment, cultural, and fashion industries, with projects ranging from printed matter to album art to music videos.

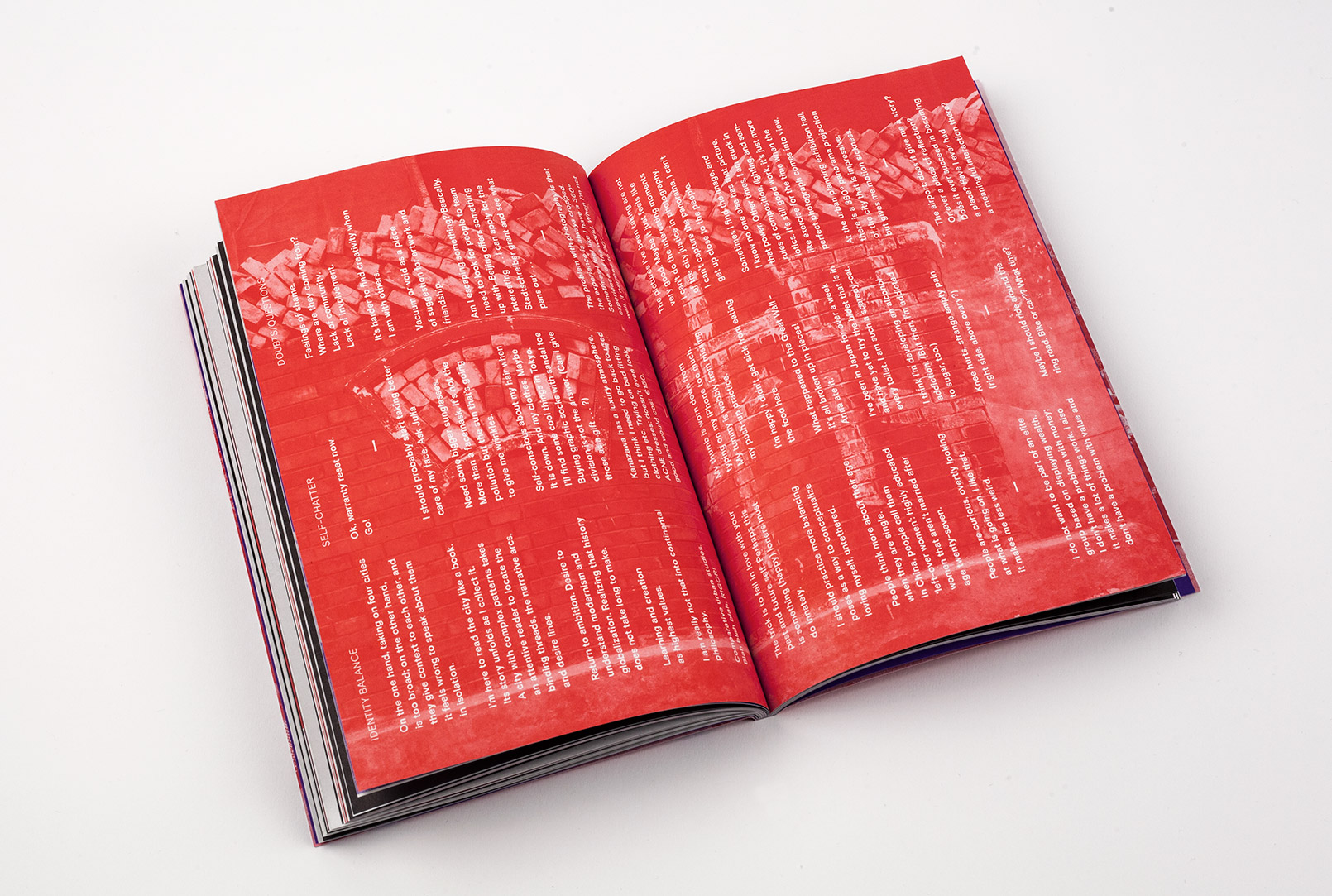

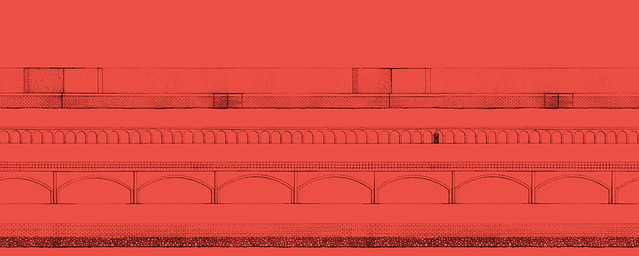

The story told by Three Pathways to Get Anywhere (Except When There is a Dead End) begins on a two-page spread that is entirely black but for three lines of text and four photographs. The photos depict the spreading dazzle of lights in the night, as if they are frames cut from a video recording of an approaching car on a dark road. The lines of text repeat the myth that when high-speed rail was invented “the first passengers worried their hearts would stop”. The next page opens to the book’s default form — white pages with one or two blue or red risograph prints, overlaid by the author’s notes and poems. The dynamism established at the text’s beginning is swapped for the impression and detail of location. This immediate switch in tempo slows the reader, going some way in mimicking the journey of the traveller: the hard bump and screech of a jet hitting the tarmac followed by a winding taxi ride from the airport to the hotel. It’s clear from here that this text is an unusual one.

Three Pathways to Get Anywhere (Except When There is a Dead End) is a work of experimental nonfiction. The book is a collaborative effort, acknowledging and even crediting the work of the phantoms who are typically hidden in the shadows behind the published work. The words and photographs are by Anna Kostreva, an American architect, artist and researcher, cut from the journal she kept as she travelled through Beijing, Shanghai, Singapore, Tokyo and Kyoto. The text is collated in collaboration with Joey Horan of the book’s publisher, Rough Beast, and it is designed by YUKIKO Studio, the design agency behind the award-winning Flaneur Magazine.

This sort of teamwork is to be encouraged — its outright acknowledgement is refreshing, and the results are, here, immediately discernible. Most striking, initially, is the book’s design. The images, often full-bleeds that form a backdrop to the text, create the fluidity of memory with their ghostly transparency, despite or maybe because of the reds and blues. They compliment the words on the page instead of dominating them, and are occasionally the book’s most captivating element.

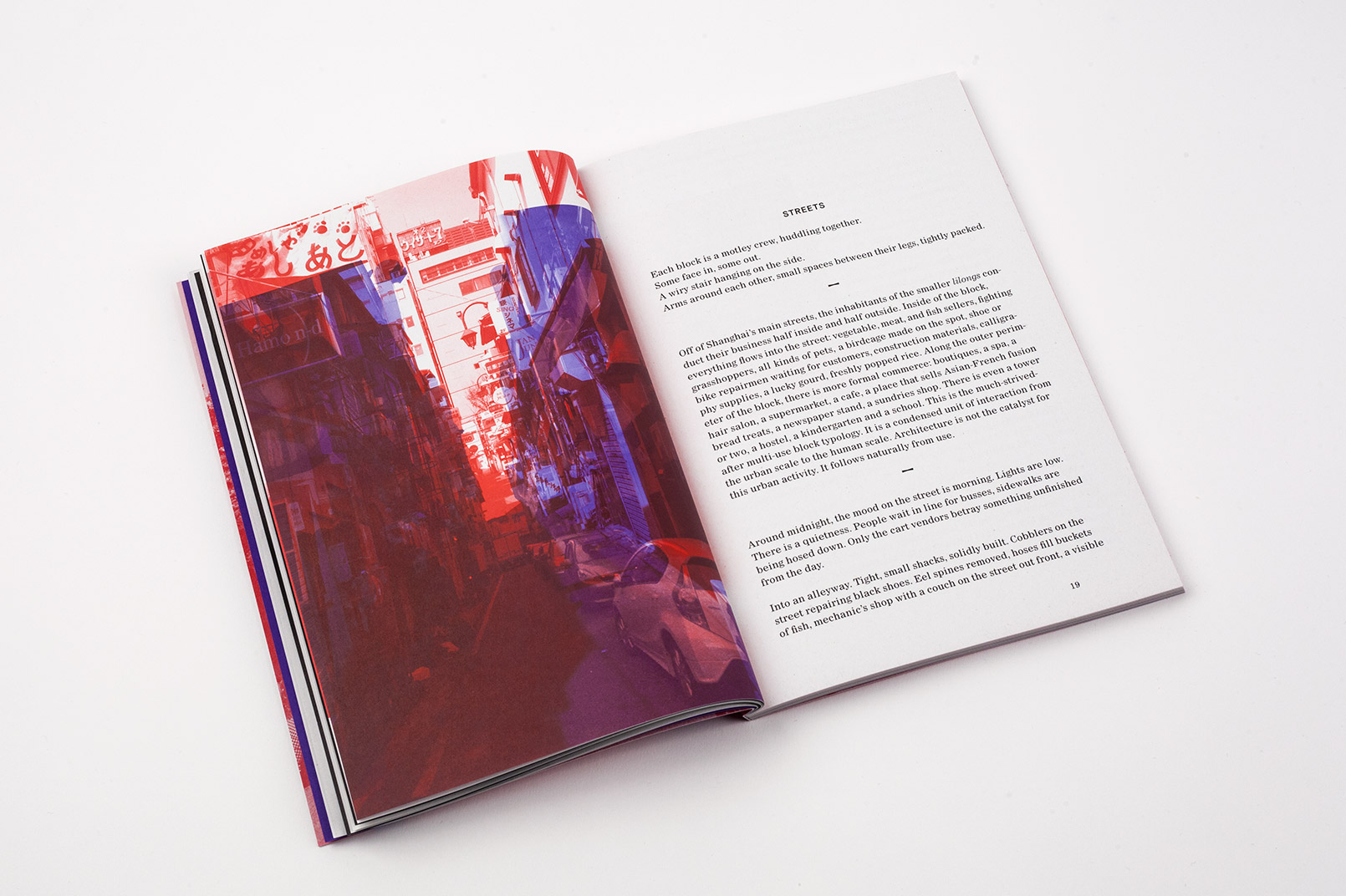

Kostreva’s writing reads like a mix of research notes and entries lifted from a travel journal. These notes have an evanescent quality, arriving sometimes as brief poems or single sentences, other times as narrative, but most often as mere impression: “Architecture is not the catalyst for this urban activity”; “Around midnight, the mood on the street is morning”; “We are happy to be in the presence of ancient trees.” This is the experiment here — not to follow a chronology or logical form but to gather the scraps of inspiration and recognition and wonder, and, in this act, attempt to capture the transient. That is, to reflect the fragmentary, disorderly way that the human mind processes the world, instant after instant.

This has a clear precedence; the attempt to capture or reflect the unfiltered experience of the “real” in art is, from this vantage point, a modernist conceit. In What Ever Happened to Modernism?, novelist and critic Gabriel Josipovici writes: “What is at issue is reality itself.” This raises an important question: is the use of a literary mode that was problematised at least a century ago—and in use for even longer — still an experiment? In his essay, ‘The Magnet has a Soul & Everything is Water’, Darran Anderson helps to frame an answer: “Modernism didn’t disappear because it never definitively appeared.” Modernist techniques have been appropriated and absorbed into writing practice, approaches that have been pushed to the edges of what is commercially viable, yes, but that are ultimately still with us as tools at the writer’s disposal.

Of course, although we have moved on from modernism proper, the desire to pin the chaos of experience to a page never left us. At the heart of the impulse is crisis — Anderson, again: “Every generation is reenacting the Great Disillusionment.” The reader of Three Pathways has the feeling of being stuffed into a suitcase, then pulled out to be shown an odd evocative sight here and there, and being whispered secrets in between. Maybe behind these secrets is Kostreva’s hidden fear that the world she set out for is not the world that greets her — these are her ripples of disillusionment. In its fragmented presentation, Three Pathways plays with existing ideas of experimentation, but such an experiment must put more at risk.

This wouldn’t necessarily be a failing at all if it weren’t for the way it facilitates Kostreva’s treatment of the cities she visits and cultures she observes. This is a book about visiting East Asia’s political and economic hubs. Rather than view each of the cities as distinct phenomena, they are regularly merged, as if one. For instance, the section titled ‘Others far from home’ pulls together her experiences with expats. In this section, the narrative jumps from Tokyo to Beijing to Shanghai and back to Tokyo without any real signposting to mark these leaps. Later in the text, one page is dedicated to shots of Tokyo while its opposite page is a discussion of Shanghai. On another page, a paragraph of Tokyo transitions to a paragraph on Shanghai. Very often it is difficult to tell where Kostreva is writing from altogether.

Presented in this way, the cities are consistently offered to the reader without nuance. Kostreva does open curious windows into these parts of the world — the chapter, ‘Art and Building, the Art of Building’, for instance, tells the story of an individual who seems glued to a single block in the world:

Yanfing lives in a tower with her family and works in the next one over. She says she doesn’t leave this corner of Beijing very often. Koolhaas’s CCTV building is close but not visible from her place. She was very happy that I visited her, like I was a messenger from the outside world.

But when the text is furthest from the danger of stereotypes, it typically conducts an about-face, curtailing itself, slipping again back into the ordinary, to the notes of a young person’s visit to a foreign land. In other words, it turns back to the orthodox. It is a naive approach to the composition of such a text, but also to distinct countries with distinct cultures. This is made worse by the use of the all encompassing term “people”. It appears with unhelpful regularity, grouping, generalising, chiseling away at difference. The ways in which the cultures of the world have become markedly uniform is a phenomenon worth exploring, as are the ways that East Asia’s hubs in particular are indicative of that, but Kostreva’s observations remain at the surface level of the tourist trail. This is possibly worst in the section titled ‘Others in Their Homeland’, as fleeting, superficial musings are noted down. “So many face masks, because people are ‘sick’” and “Chinese women will darken their eyebrows.” Kostreva’s recognition of the cultural vandalism brought about by globalisation is prevalent, as she encounters the foreign and thinks that, because of the forces of the global market, it “becomes familiar”: “This is Chinatown in China.” She goes to an international art show and is disgusted by what passes for art, claiming: “The art is uninteresting, bait for the basic globalized art consumer.” She finds the influence of globalisation, too, in the banal: “Dependence on oversized smartphones … Do people in Japan make friends? So quiet.” But the damage—and the attendant feelings of disquiet—caused by globalisation is rarely the point, never skewered for analysis, and is just as often pocketed for a comparison to the West: “Outer Shanghai is kind of like outer Atlanta, but with more debris and gray soil.”

This behaviour reduces the text to a travel journal, a Moleskine cut up and coloured in with highlighter. This description undermines the work of the design team, but it is useful in illustrating the content and rendering the text’s claim to be experimental as a misguided one. In a poem entitled ‘Identity Balance’, of the project, and her tour through the five cities, Kostreva writes, “They give context to each other, and / it feels wrong to speak about them / in isolation.” There is clearly an awareness of this forced coalescence, then, but the failure to engage with the cultures instead of commenting from the outside looking in devalues the text. This is a lazy kind of cultural analysis. The reader that who has visited these cities will recognise the sights Kostreva singles out: the Beijing smog; the sobering up that daylight forces on Harujuku; Japanese train conductors bowing as they enter then leave the cabin; morning Tai Chi (and dancing and badminton and singing) in Beijing parks; Singapore’s incongruous yet charming mix of the tropical and colonial. Are these alone worth visiting a city for? Are these alone worth shaping a book around?

By building her text in this way, Kostreva inadvertently goes to some length in demonstrating the limitations of the tourist trail. From this perspective, this isn’t the city. This isn’t the culture. This isn’t a people. This isn’t a lifting away of the layers of history. The visitor’s view is a limited one, the tourist’s even more so. In a lesson for all travellers: the tourist is not in a position to judge. Kostreva avoids judgements outright; these are her observations, sometimes considered, sometimes superficial — this is Kostreva looking at architecture in China or Singapore or Japan. But her judgements of these cultures are cast by making the decision to cluster five distinct cities from three distinct countries together in the method of the travel agent creating a holiday package deal. Rather than cutting through the confusion of place, the decision to put them in a sack and shake — the book’s primary attempt at experimentation — adds to it. Denying the impulse to completely decouple the cities is very nearly fatal to the text. The book’s clearest failing is that Kostreva’s strengths are architectural and not anthropological, but it is her writing on the latter that makes up the majority of the text, manifesting as the fleeting, ill-considered observations of a holiday-maker on the sightseeing route.

In contrast to this, the section titled ‘Devotional Gods of Learning and Creation’ succeeds because it draws on inspiration from its surroundings while, paradoxically, forgetting where it is entirely. It consists of a two-page spread, one page black, the other white, with overlapping red and blue risograph prints of ambiguous photographs as well as a poem listing characteristics and matching them with Kostreva’s friends and family. She writes: “Of memory (dad) / Of obscurity (Peter)”. The mysterious, personal nature of this prayer for loved ones, the transition from white to blue to red which, overlaid, makes a colour entirely uncertain of itself, and then finally to black on the next page, fashions something surprising and singular.

It becomes clear, then, that when the design elements are scissored out, too often missing from Three Pathways is the shock of the new. This hurts the text in two ways: firstly, it leaves the reader with a superficial view of these cities that limits any richness and difference that they have to offer; and, secondly, it curtails the book’s aspirations to escape orthodoxy. As Barthes observed: “To be modern is to know that which is not possible anymore.” Kostreva goes looking for the new, both figuratively and literally, yet struggles to find it. It’s a problem created by the global free market, yes — but also the writer herself.

Among the more successful elements of text is the intensely personal experiences that are determined not by location but by sheer incidence or inspiration. “I don’t want to live anywhere,” Kostreva writes. “I want to exist everywhere, and experience many things. Is that unusual?” And notes like, “Am I escaping something?” and “I don’t belong anywhere here.” But like the dynamism that is established on the open pages and then forfeited on the next, the sheer energy of these segments, are quickly splintered, rambling as journals can do: “Trying out Josh’s e-scooter! Playing catch and doing handstands in the street with Daniel.”

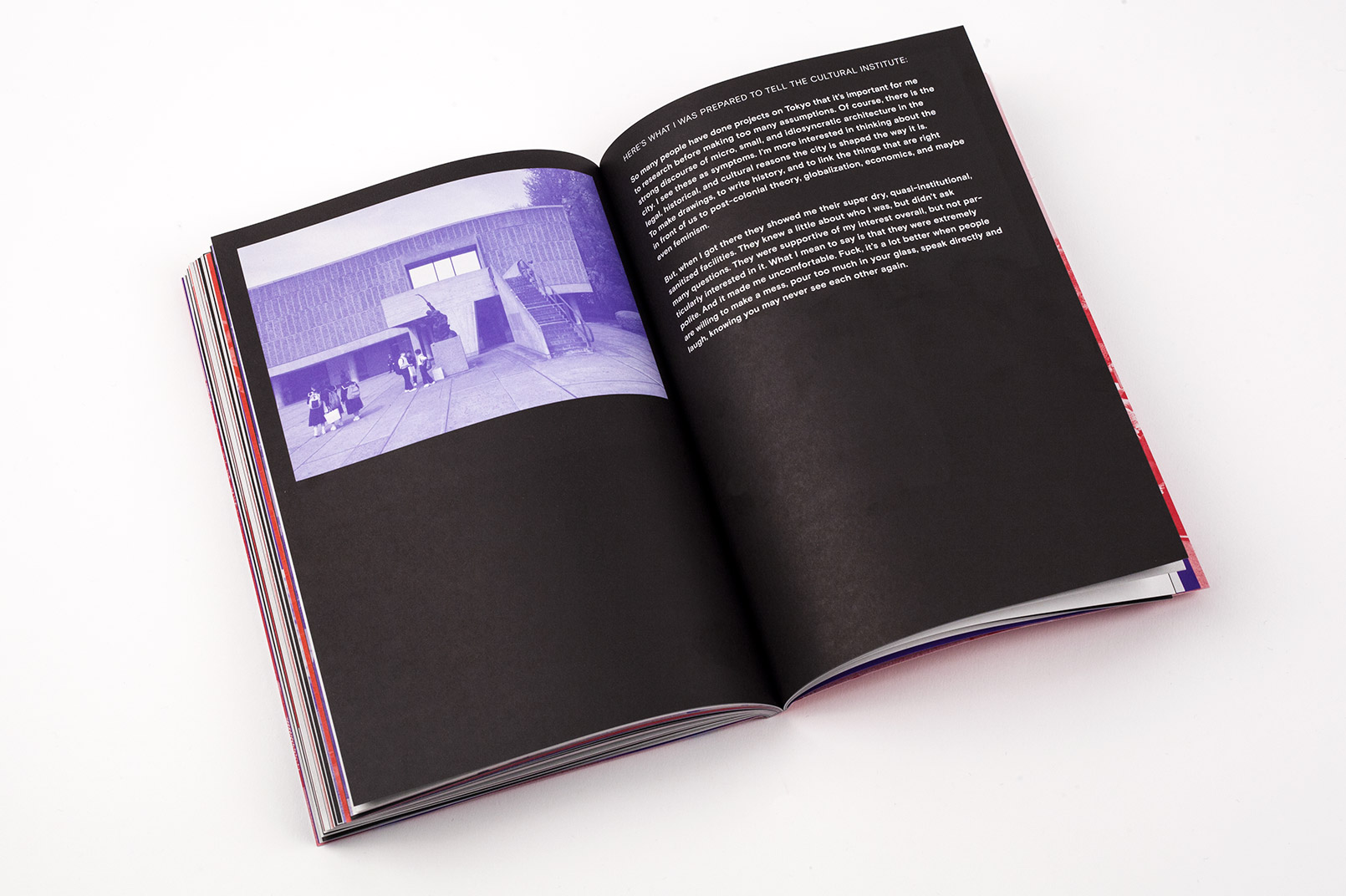

It should be no surprise that Three Pathways is most compelling in its commentary on architecture and its function as symbol and spectacle: “Shanghai is a mask, a transitional zone, a threshold”; “City as a chess game”; “If you want to practice architecture, politics, economics, and memory are your media. They must be held in composition as tightly as the bricks and mortar.” These portions of the text are the most illuminating – the main area of differentiation Kostreva can bring to her limited observations of the cities. But it also demonstrates an engagement with the surroundings, research, maybe – something more than a momentary gaze from a safe distance. For instance:

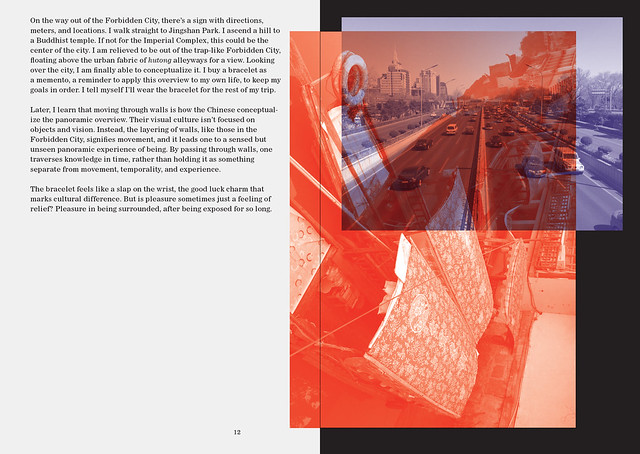

The layering of walls, like those in the Forbidden City, signifies movement, and it leads one to a sensed but unseen panoramic experience of being. By passing through walls, one traverses knowledge in time, rather than holding it as something separate from movement, temporality, and experience.

Kostreva is also successful when she combines her interests, like when the architectural is melded with the personal for the sake of humour: “What happened to the Great Wall — / it’s all broken up in pieces! / Anna ate it.” Or intimacy: “Going up the mountain, I’m nervous about running out of time.” Or when it is evocative: “Balancing on one foot, / alone in a dark tunnel of orange Torii, / lamplight striped shows across the path.” But too often the subjects are split altogether and Kostreva’s attention strays too far from the subjects she knows best.

So, what are Kostreva and Rough Beast concerned with — what are they trying to do? To make a stylish and unusual thing. They get close — Three Pathways is pretty, it is different. It nudges at the idea of book-as-object without ever quite taking it that far. This method makes little of much — arguably, of the 45 million square kilometres of the continent of Asia.

Near the end of the book, in modernist fashion, comes epiphanic moments. Kostreva writes: “But every building has mistakes. I only see them now that I’ve made some mistakes myself.” This is followed by a flurry of discussion of local architecture. It’s the strongest part of the book. “I am trying to create an understanding of time, materiality, history, and culture.” With this sudden bloom of inquisition and thought, it finally becomes clear that, with this book, Kostreva and Rough Beast are indeed attempting to produce something more profound than what they ultimately end up with. And, now that this building is built, a monument of true collaboration, they will hopefully improve upon their successes as well as recognise their mistakes, and create something even better next time.

- Tristan Foster

In a new book of experimental non-fiction, architect and writer Anna Kostreva has collaborated with editor Joey Horan to produce a kind of travelogue-cum-dérive – a collage of her own experience as a contemporary flâneur around the cities of East Asia. Fiona Shipwright takes Three Pathways to Get Anywhere and ends up – positively – at a dead end.

There’s a line in Three Pathways to Get Anywhere, a new book by architect and writer Anna Kostreva, in which the author describes the Zen school of Buddhism as being “radical” on account of “valuing individual experience” over that resulting from a shared, collective adherence to a doctrine.

That very Zen-like individual experience – albeit one charged more with escapism than self-reflection – leads the narrative in the book itself, recently published by Rough Beast and produced in collaboration with editor Joey Horan, which chronicles six weeks of travel through China, Japan, and Singapore in March and April 2015. Presented as “a work of experimental non-fiction on travel and cities in East Asia” it traces a path through a constellation of urban environments. This is exactly the kind of experience that the modern day flâneur is encouraged to upload and “share”, continually broadcasting an edited version of their personal here-and-now. But a paradox ensues. For such experience has little hope of remaining “individual” when it is prized less for its value to a singular observer but more to attract the attention of multiple, real-time external observers. As the narrator laments at one point: “the problem with photography is the experience is always cropped”.

It is some relief then, away from the rapid-fire environment of infinite scroll-land, to find Konstreva and Horan’s work plays not only with the cropped image but also with all that lies beyond its frame. In doing so the author effectively describes the act of travel through differing aspect ratios – from a top down, widescreen view of the space between Beijing’s vast ring road infrastructure to the cramped framing of the sky resulting from looking up in a backstreet courtyard, in a space created by accident rather than design.

Fluctuations in speed and velocity also occur throughout the book: the lone walker seeking to lose themselves in the fabric of the city gives way to the frantic energy of selfie-stick wielding arms that extend and gesticulate wildly from a crowd of tourists. An airport bus hurtles down the motorway towards a city centre whilst a child’s electric scooter takes a more meandering pace along a pavement.

As well as speed, the experience of the duration of time also plays an important role, particularly with regard to the way the built environment is treated. Kostreva’s exploration of urban spaces tends to be human-focused, contrasting the “slowness” of construction with the swift manner in which architecture is adopted, appropriated and adapted by its inhabitants. It is these latter processes that seem to most fascinate the author, for whom: “architecture is not the catalyst for this urban activity, it follows naturally from use”.

For this reason, whilst it’s largely a background presence, visually chopped up and layered, architecture is perhaps the most important character in Three Pathways to Get Anywhere. The fragmented, fleeting nature of foreground events require architecture as a means of context upon which to hang experience, a point from which to remember. For example, one of the texts, “Movement”, conjures the sense of dissolution traditionally associated with the classic Augé-esque non-place, complete with reference to spaces of transit, yet gives just enough detail to turn them into actual, lived, active places.

Kostreva’s use of both top-down and bottom-up perspectives is particularly interesting given that most recently it is the view from a great height which has come to be privileged in the context of “UrbEx” (urban exploration) – usually resulting from spectacle-seeking attempts at breaking in and trespassing. The “conquering” of urban sites, of the ticking-off of sights and providing (usually visual) documentation of missions accomplished (nearly always with the protagonist somewhere in the frame) seems to be most concerned with proving: “I was here” (often whilst they’re still there). The accelerated nature of this approach is affecting our experience and understanding of places, somehow depriving us of what lies beyond the frame. Whilst it may provide a treasure-trove of archive material, it doesn’t communicate much about the spaces themselves – just that someone went there. Somewhere along the way, the dérive has, well, gone off track.

Three Pathways to Get Anywhere picks up this thread, aptly alluding not only to the global locale we now inhabit but also one of its main drawbacks: not-so-individual experience. And somewhere along the way the conflicted desires of the lone walker, moving against the backdrop of the city is revealed: “I don’t want to live anywhere, I want to exist everywhere, and experience many things.” To satisfy this “I”, the self, seems to require the dissolution of that very same self. On this point the text from which the book’s title is borrowed offers some clues:

“Three pathways to get anywhere

except when there is a dead end,

a hiding place

a place to pause.”

Perhaps this is really why we travel: not to move at all, but to pause between movement; not seeking to get anywhere in fact, but to deliberately seek out a dead end instead. – Fiona Shipwright

Mehr! Theater Hamburg, F101 Architekten, 2012-2015

Built Project. Part of the Grossmarkt in Hamburg is converted into a multi-use hall. read more >

Built Project. Part of the Grossmarkt in Hamburg is converted into a multi-use hall. read more >

Berlin: A Morphology of Walls, 2010-2014

A book of research about the walls of Berlin and their architectural traces. Published by Archive Books. read more >

A book of research about the walls of Berlin and their architectural traces. Published by Archive Books. read more >

Broken Kilometers, 2012

An installation made for an experimental exhibition / dance party titled "The Destructibles." read more >

An installation made for an experimental exhibition / dance party titled "The Destructibles." read more >

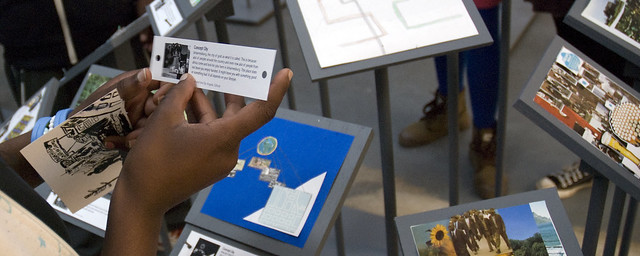

All My Cities, 2009-2010

My Fulbright project investigating youth perspectives in post-apartheid Johannesburg, South Africa. read more >

My Fulbright project investigating youth perspectives in post-apartheid Johannesburg, South Africa. read more >

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.