Franco Nasi, Translator's Blues, Trans. by Dan Gunn, Sylph Editions, 2016.

This funny, engaging book tells the story of an Italian naif who both visits America and travels around his home country, reflecting humorously and movingly on the oddity of what he finds in each place. Through the eyes of his guilelessly perceptive imaginary traveler, Franco Nasi reminds us anew of the fundamental strangeness of the world when it is viewed with fresh eyes. It is the space between that experience of new discovery, Nasi shows, and the version of it that we put into words--and set awry when we attempt to translate it into a new language--that generates melancholy and even disenchantment.

At once a winning story and a reflective essay, this brief book by one of Italy's most celebrated writers on translation is a celebration of the gap between languages, of the spaces that both unite and divide us.

Charged with the task of bringing a piece of text to life in another language, for another culture, and possibly also for another moment in time perhaps centuries after it was originally conceived and recorded, the translator stands armed with words alone: “imperfect, approximate, or a tad reductive”. But, employed with skill, sensitivity and creativity; words can facilitate a little literary magic.

Translator’s Blues, the latest addition to the Cahier Series of the American University of Paris (#26) is an imaginative discourse on the dilemma of translation – a meditation on the interplay between language and culture, facilitated through words; an elegy for what is gained and what is lost in the process. Italian translator Franco Nasi adopts the voice of a naive alter-ego who is, like his creator, a translator who hails from the province of Regio-Emilia where he was born and expects he will die. His home – with its mountains, Parmesan cheese factories, and cemeteries laid out like miniature cities behind high walls – is a place which makes sense to him, a world that is idiosyncratic but familiar. He is grounded there.

When he chances to befriend an American architect who is visiting his fabled region of Italy, he is offered an invitation to travel to the States in return. After a brief visit to Vermont, our translator finds himself in Chicago where his host is presently employed. As our erstwhile hero makes his way through the linguistic landscape of America he finds himself exploring of the boundaries of language that are blurred when one endeavors to navigate the tricky waters that lie between one culture and another. Through an account of his adventures and encounters he orchestrates, with insight and and a measure of impish delight, an argument that translation is, at its best, an inexact art form. However, rather than seeing that as a limitation, he celebrates the challenges, possibilities and rewards of bringing a piece of literature to new audiences that would otherwise be denied access by the borders of both language and culture.

Our narrator’s journey of discovery starts inauspiciously on a snowy Sunday morning in Chicago when he sets out to purchase non-alcoholic beer from a nearby shop. Bemused by his inability to procure alcohol of any description before 11:00 AM, he inquires of his host as to whether this is a daily reality or one confined only to the one day. He learns that it is, in fact, a law applying only to Sundays, to what are known as the “blue hours”. Blue. This is a word that has a special impact for our translator. He had just finished reading William H. Gass’ On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry. He was given the book so that he could assess its suitability for translation. Thus it was with a translator’s eye that he read it, and he found himself rather out of his range. He was inclined to wonder if attempting to translate a book like this, with its multi-layered references to the significance of the colour blue, would be at all possible. References in some instances, such as those with sexual or potentially pornographic overtones, would likely be rendered nonsensical to a culture that tended to associate the same arena with the colour red. It would, he feared, surely induce in him a state of melancholy:

“… a malady that takes hold of you whenever, after a thousand false starts, you find yourself being invested by an overwhelming sense of inadequacy and impotence. This blue-tinged malady makes the translator wish that Babel and the multiplication of languages were only a legend, and that all the various languages in the world did not exist and had never existed. With melancholy comes nostalgia for an ur-language, in which all colours and all their meanings were the same for everyone, in which plants were identical for all and sundry; in which flowers, and sounds, and ceremonies, every object and sensation, and belief was expressed in a single, universal, manner, in which a rose was a rose was a rose.”

All the culturally and linguistically entrenched peculiarities of blue aside, Nasi allows the shade to colour, if you will, much of the exploration of the art of translation that follows. His translator is led, most immediately to a famous Chicago blues bar. As he soaks up the atmosphere and the music, he reflects on the translation of African traditional music to America, facilitated through the songs that black slaves brought with them. Typically based on a pentatonic scale, these songs are echoed in the adaptation of one musical “language” to instruments designed to the specifications and precision of the chromatic scale. As a consequence, notes tend to slip a little out of tune, to bend, and acquire the nostalgic, mournful tone, the blueness, that we associate with the blues. On his way home he contemplates the resonance between the music he has been enjoying and his craft:

“Could it be that any translation, if it seeks to be more than a cold and sterile transposition, must contain blue notes? A translation needs blue notes to hint at an elsewhere, at nostalgia, and with nostalgia the tension provoked by unappeased desire for whatever is distant and unreachable. As William Gass puts it, ‘So it’s true: Being without being is blue.’”

From this point on our hero chances to meet a well-known American poet who, it turns out, is seeking a tutor to help him improve his Italian. So the two begin to meet regularly. Over the course of their acquaintance the poet gives his new friend a volume of his poems. Seeing this as an opportunity to exercise his own English skills, with the added advantage of being able to check his success against the original author’s perceptions, the protagonist asks if he might translate some of the poems. The poet seems pleased with the resulting translations, even if they might at times be less than exacting. So talk of publishing the Italian versions arises and a publisher is sought. Suddenly the poet’s self-appointed “official” translator emerges and demands that a halt be put to the fledgling enterprise – after all, audiences are accustomed to one voice, to offer an alternative would certainly be disorienting.

Nasi’s translator backs down. But at the same time he wonders about the “versions” of writers such as Homer, Sappho or Aristophanes that already exist. He envisions the silence of the library where the respective translations must sit shoulder to shoulder on the shelves, to be broken once the lights are turned off and the key turned in the lock:

“Of a night, there must be some turbulence in the library stacks, what with all those competing voices. And it’s clear that the music does indeed change according to who is playing – and just as well too: what a bore it would be to hear over and over Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’ Symphony in the way it was played in public the first time, on 7 April 1805 in the Theater an der Wien. To translate is to betray – tradurre è tradire – and only through betrayal is a writer’s voice kept alive. To the liveliness of this voice in time will correspond the number of voices multiplying it, so permitting it to dialogue across the ages.”

Nasi goes on to expand on this fundamental idea. Looking at translation close to the source – that is, within the author’s lifetime – has a particular value, especially when the author is engaged in the translation process. However some authors, and Nasi points to a few of his fellow countrymen here, may run the risk of insisting on a degree of literal accuracy, as they perceive it, that could hinder an emotionally and culturally authentic transition to a foreign language. And to round out his argument he allows his alter-ego to experience the shock of receiving a copy of his own translated book, which is, in reality, the very book the reader happens to be reading. He fails to recognize it at first, his child released into the world now returning and standing at the doorstep – changed but somehow the same and possibly richer for the experience of immersion in another language and culture. Just as our Italian narrator returned from his own trip beyond the borders of Regio-Emilia informed and enlightened.

An essay within a most charming story, Translator’s Blues offers an entertaining, thoughtful reflection on the relationship between translators and the works they attempt to realize in another language and culture. With humour and a gentle wisdom, Nasi explores what can be preserved, what is lost, and the responsibilities that, he would argue, have to be surrendered in the process of translation.

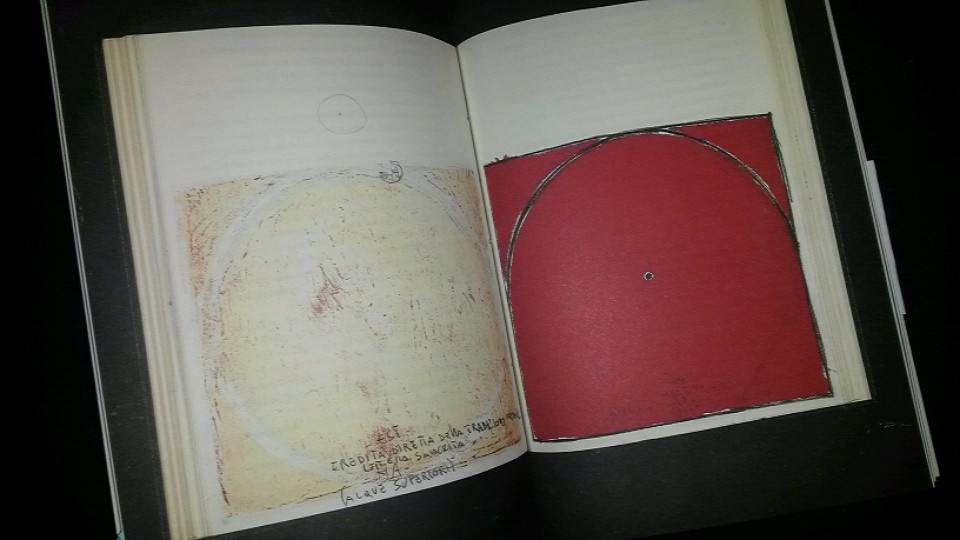

An essay within a most charming story, Translator’s Blues offers an entertaining, thoughtful reflection on the relationship between translators and the works they attempt to realize in another language and culture. With humour and a gentle wisdom, Nasi explores what can be preserved, what is lost, and the responsibilities that, he would argue, have to be surrendered in the process of translation.Franco Nasi is a writer and translator who has taught Italian language and literature in the United States, and has translated into Italian a number of writers and poets including S.T. Coleridge, William Wordsworth, J.S. Mill, Billy Collins and Roger McGough. Translated by Dan Gunn and paired with illustrations taken from a notebook kept by Italian artist Massimo Antonaci, Translator’s Blues will be released in February, 2016. - Joseph Schreiber.

http://lithub.com/translators-blues/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.