Wu He, Remains of Life, Trans. by Michael Berry, Columbia University Press, 2017.

read it at Google Books

On October 27, 1930, during a sports meet at Musha Elementary School on an aboriginal reservation in the mountains of Taiwan, a bloody uprising occurred unlike anything Japan had experienced in its colonial history. Before noon, the Atayal tribe had slain one hundred and thirty-four Japanese in a headhunting ritual. The Japanese responded with a militia of three thousand, heavy artillery, airplanes, and internationally banned poisonous gas, bringing the tribe to the brink of genocide.

Nearly seventy years later, Chen Guocheng, a writer known as Wu He, or "Dancing Crane," investigated the Musha Incident to search for any survivors and their descendants. Remains of Life, a milestone of Chinese experimental literature, is a fictionalized account of the writer's experiences among the people who live their lives in the aftermath of this history. Written in a stream-of-consciousness style, it contains no paragraph breaks and only a handful of sentences. Shifting among observations about the people the author meets, philosophical musings, and fantastical leaps of imagination, Remains of Life is a powerful literary reckoning with one of the darkest chapters in Taiwan's colonial history.

“A massacre involves a fundamental betrayal of life by life itself”: searing experimental novel by the pseudonymous Taiwanese writer Wu He.

Wu He the writer—the name means Dancing Crane—and Wu He the character and narrator are not quite one and the same, though this novel, originally published in Chinese in 1999, recounts events in the author’s real life. Following modest success as a writer of short stories and literary novels, Chen Guocheng took up a historical and anthropological investigation of an event that Taiwan had long forgotten: the massacre of hundreds of members of Taiwan’s Atayal tribe by Japanese colonial police and soldiers nearly 90 years ago. Now called Wu He, Chen ascends into the country of the Atayal to explore what happens to a people brought nearly to extinction by an act of genocide. In an onrushing, stream-of-consciousness narrative that takes a single paragraph over the length of nearly 300 pages, Wu He answers that question, drawing on the voices of native people known simply by names such as Elder, Cousin, and Girl. The people are suspicious: what, they wonder, is a stranger doing poking around in their past? “There’s a hell of a lot to research when it comes to you Han Chinese,” says one bluntly, “why don’t you go home and research yourselves?” It’s a good question, one that doesn’t deter Wu He, who tucks into the indigenous fare of flying squirrel stew and the like and, as the anthropological saying has it, goes native—though not quite as native as Cousin might like, for she encourages him to chuck it all and head deeper into the mountains to become one of them and “lose yourself for the rest of your life!” In the end, the anthropologist becomes as much an object of study as the people he is researching, with all sorts of implications.

A brilliant but immensely challenging work, of great interest to students of contemporary Asian fiction—and of the literature of atrocity and remembrance as well. - Kirkus Reviews

It’s taken 18 years for Wu He’s critically lauded Remains of Life to appear in English translation, and a glance at the text readily explains this delay.

This is an avowedly experimental novel that revolves around one dreadful event. On October 27, 1930, at a sports meeting at Musha Elementary School, on an aboriginal reservation in the mountains of Taiwan, a bloody uprising took place against the Japanese. By noon, the headhunting ritual had left 134 of the occupiers decapitated. The colonial power’s response was to mobilise a 3,000-strong militia, roll out the heavy artillery, put planes in the air and deploy poisonous gas in a ferocious act of genocide that saw the near extermination of the Seediq tribes.

The Musha Incident, as it came to be known, had been forgotten by many Taiwanese, but the book led to a resurgence in interest, and a new evaluation of its significance.

Remains of Life has little concern for orderly narratives or neat conclusions: it has no chapters or paragraph breaks, and few full sentences. It combines a historical study of the Musha Incident, the Seediq and surviving tribe members (the “remains of life”), philosophical ruminations on time, the human condition, history, sexuality and violence, and sudden lurches into fantasy and even metafiction.

Wu He’s writing shares the stream-of-consciousness style of Ulysses by James Joyce.

The style has been called “stream of consciousness”, but perhaps “river of prose” would be a better label, because Wu He’s writing does not leap about with the sudden non sequiturs of the human mind (as most famously seen in James Joyce’s Ulysses [1922]). It is an endless flow of writing, of thought, of memory.

The book is also largely about Wu He’s writing of the novel, his stay in the reservation, his relations and interactions with surviving members of the tribe and his analysis of the incident.

This metafictional strategy allows the narrator/author to circle around the Incident, to fictionalise his experiences and reflections, rather than going for conventional fictional narrative or realistically (if artificially) documenting his experiences. One could almost call it gonzo, though the book has none of Hunter S. Thompson’s frenzied, bitter prose.

None of the radical, experimental techniques deployed by Wu He are unique, but as the reader is so strongly aware of them, they deserve consideration.

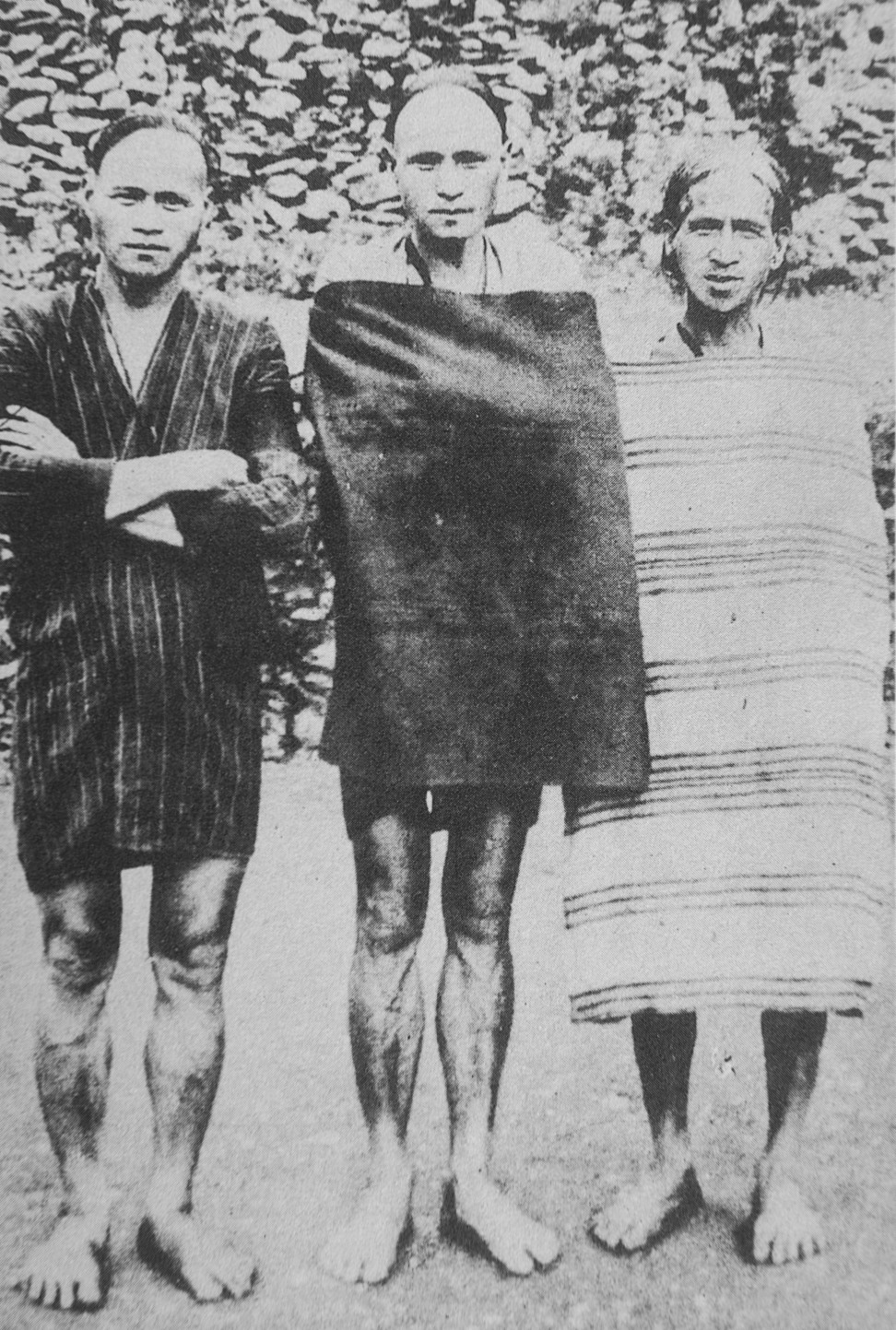

Mona Rudao (centre), chief of the Seediq tribe, in 1930.

The most obvious is the endless stream of uninterrupted prose, with perhaps 20 sentences in the entire book. This has some antecedents: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) was famously written single-spaced and without paragraphs on a single 120-foot typewriter roll that he had glued together, the better to capture a spontaneity analogous to improvisational jazz. Scottish author James Kelman likewise has produced a number of short stories without paragraph breaks, in an attempt to convey the unrelenting quality of the protagonist’s misfortunes and misery. In both cases, the continuous prose conveys an inexorable energy or force.

This is less apparent in Remains of Life, which can veer from poetic to banal in a few short lines. At one point, we read “Old Daya thanked Young Wolf for his hard work taking care of the inn, he knew enough to preserve the original look of the first floor, the hot springs tubs on the second floor were all kept clean and the comforters were all properly folded neat and tidy”, but shortly afterwards are flabbergasted: “this was a time that many of the Mhebu mothers displayed the great courage of Atayal women, for some reason many of them hanged their children from the trees [and] throwing their children from the high cliffs as they passed by Valleystream”. Banality and horror coexist, as in life.

Wu He – “Dancing Crane” – is the pen name of Chen Guocheng, and his use of names is important. Characters have somewhat cartoonish or emblematic names, such as Girl, Nun, Deformo and Drifter. This technique, too, has been used elsewhere, from William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch (1959), the cast of which includes The Sailor and The Buyer, to Irvine Welsh, who helpfully names characters such things as Sick Boy and The Victim. Similarly, Taiwan is referred to as “island nation” and the Chinese as “People from the Plains”.

This makes the cast feel archetypal: Girl becomes representative of all women on the reservation, perhaps even of all womankind, and Taiwan emblematic of all islands dominated by “the mainland”. Though the details are intensely local, this technique attempts to universalise the lessons and details of the Incident. It doesn’t always work – what feels innate for someone Chinese does not always transfer outside of that mindset – but it’s a significant move by Wu He.

His ruminations are frequently superb – passionate, insightful and earthy. Consider this, on the dehumanising effects of colonisation on the indigenous tribes: “[…] in 1911 a war broke out resisting the Japanese order for tribesmen to turn over their rifles because rifles were the most prized possession for heroic hunters, how could they possibly hand them over because of some ‘political’ excuse the government came up with, this continued until the Japanese bombs ended up on their doorsteps and they finally unwillingly handed over their rifles, but ever since that time the tribal hunters’ ‘dignity’ suffered a terrible blow, the same year they also resisted the order to hand over their collections of human skulls, because they were important sacrificial objects in their rituals […] giving them up was like handing over their dignity, and once it was later forbidden to display their skull racks there wasn’t even a place to put their ‘dignity’ anymore, tattooing was prohibited in 1917 and the following year they started instituting short hair for men and outlawed the practice of otching, a tribal rite that disfigured the front teeth, after all of this that and the other the Japanese may as well have dictated the length of the tribespeople’s ass hair […]”. One does not have to look far to find modern equivalents, such as the ban on religious names and “abnormal” beards in Xinjiang.

Remains of Life is challenging but not unrewarding, and it is, of course, politically and historically important. While some literary techniques become mainstream, others remain experimental for a reason. The absence of chapters, paragraphs and sentences make Remains of Life a daunting tombstone.

Yet it has moments of solemn tragedy and deep pathos, of fiery passion and humane insight, which keep you turning the pages. Some may enjoy the disruptive effects of its style, or the tale of a man haunted by history, or Wu He’s attempts to remember a forgotten people and to understand dreadful events. Remains of Life has all that, and more. - Mike Cormack

This was the massacre of 134 Japanese at the Wushe’s elementary school’s sports ground on Oct. 27, 1930 by the Atayal community. It was followed, beginning the next day, by a Japanese assault on the Atayal with heavy artillery, bombs (including experimental incendiary bombs) and an internationally banned poison gas that resulted in the reduction of the group from around 1,200 to some 500.

A third attack took place on April 25, 1931 in the form of another Japanese assault, this time on a detention center, in which almost 200 more Aborigines were killed, with over 100 of them decapitated. The Atayal survivors were forcibly moved to a site 40km from Musha known today as Qingliu, formerly called Chuanzhongdao, or Riverisle. These survivors are the origin of the term “remains of life.”

Taiwanese author Wu He (舞鶴; real name Chen Kuo-chang, 陳國城) went to Qingliu in the 1990s to investigate these events and try to find descendants of those involved. The eventual result was this stream-of-consciousness novel, now translated into English by Michael Berry.

The original book received critical acclaim in Taiwanese and other literary circles, formed the basis of a two-part film Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale (彩虹戰士:賽德克巴萊, 2011) and a documentary two years later called Pusu Qhuni (餘生—賽德克·巴萊). It was translated into French as Les Survivants, also in 2011.

A sensation the original may have been, but it doesn’t make for easy reading in English. There are no paragraph breaks anywhere in the entire book, and only a handful of periods. The narrating voice veers widely, from philosophical speculation as to what makes human beings capable of such violence to incidents the author experienced in Qingliu. Tamsui, where the author lived for many years, also features — he writes of “watching the colors of night move in on the nearby mountains and river” there. But the translator in his Introduction twice calls it “a difficult text,” and even goes as far as to refer to Wu He’s “sometimes nonsensical ramblings,” and passages in the book that he found “challenging or just plain weird.”

It’s true that there are attempts to discriminate between the inhumanity of the original massacre, its worth as an act of resistance and the status, heroic or otherwise, of its leader Mona Rudao and it’s being in the Aboriginal tradition of a ritual head-hunt. But such an analytical approach doesn’t dominate. Instead, what we have is an experimental novel whose stream-of-consciousness isn’t the ideal format for a balanced historical evaluation.

Nevertheless, at one point the run-up to the 1930 Wushe Incident is outlined — the unsuccessful 1911 attempt by the Japanese to get the Aborigines to give up their arms and ammunition (perceived as an assault on the dignity of a hunting culture), the order the same year for them to hand over all collections of human skulls, the 1916 prohibition of opium consumption, the 1917 prohibition of tattooing, the 1918 command insisting on short hair for men and the outlawing of the traditional practice of deforming the front teeth of adolescents and the 1922 banning of indoor burials. Then, in 1926, the Atayal handed over 1,319 rifles and 8,086 bullets to the authorities. Clearly the advice of one of the first Japanese to set foot on Taiwan was being followed: “If you want to colonize the island of Taiwan,” he’d said, “you must first tame the wild savages.”

Wu He certainly never comes to any conclusions about the Wushe Incident and what followed. He says, in one of many rambling, discursive pages, that he feels the time has come for conclusions, and hints at a few: that many Aborigines refused to take part, so the issue was controversial even before the first massacre happened, and that the state of affairs prior to 1930 was not so dire that the very existence of the communities was threatened.

But there is nothing final about such thoughts, and indeed Wu He writes that he wishes that “during my walks round this island nation I was able just to deeply observe and didn’t have to take any notes, raise any criticisms, or offer any conclusions.” There’s something very American about this, calling to mind Melville, Whitman or Thoreau, and, of course, it’s also an attitude that tends towards the literary rather than the historical. After all, no informed reappraisal of the Wushe Incident would be hailed as literature in the way Remains of Life in its original Chinese form has been.

Traditional novels contain a chronologically-developed plot and characters who are defined, among other things, by the way they speak, and Joyce retained elements of both in Ulysses. There is no trace of a developing plot in this book, however, but there are characters — among them Girl, a grand-daughter of Mona Rudao; an affectionately depicted half-wit initially called Mr Weirdo but later referred to as Deformo; and a Buddhist nun, simply called Nun, who has set up a makeshift shrine in a freight container on mountain land designated by the government as out-of-bounds.

My conclusion about this novel is that, a classic though it may well be in Chinese, it doesn’t quite have that quality in English. Reading it didn’t give me much pleasure, for instance, and great literature always gives pleasure. But it’s important that such a major work in contemporary Taiwanese fiction should be accessible to English readers so we can at least have some idea of what all the fuss is about. And maybe some readers will get more from it than I did. Even so, anyone embarking on Remains of Life should be prepared at the very least for a rough ride. I wasn’t that surprised to read that Michael Berry took over 10 years to complete this translation. - Bradley Winterton

The 'Musha Incident' is a famous and notorious one in the history of Taiwan. On 27 October 1930, aboriginal villagers in the then (since 1895) Japanese colony of what we now know as Taiwan attacked those assembled for a sports meet, killing 136 Japanese. The aboriginal tribes still practiced headhunting rituals, and the Japanese victims were decapitated; retaliation, when it came soon later, was devastating, decimating the Atayal tribe, with its few surviving members then relocated to a reservation some forty miles away.

Remains of Life is essentially a novel in which the author, writing in the first person, examines the Musha Incident (and the 'Second Musha Incident', an inter-tribal headhunting attack) and the fall-out and consequences over the decades since. Wu He lived in Riverisle, as the place where the Atayal were exiled was called, and spoke with survivors and their descendants -- the: "Remains of Life who had survived the calamity" --, and his account is a mix of reporting, documentation, analysis, and fiction. There is a strong autobiographical element, as Wu He is very much part of the story -- describing what he experiences and who he encounters -- and his commentary includes his own opinions, and his own struggles with writing about this subject: it is a personal story, too:

to make a sincere attempt at exploring the erratic nature of my own life over the past several years through this novel

Form is influenced by content: one of Wu He's struggles throughout is how to write on the subject, and how much traditional structure to impose on his writing:

Writing is unable to extract itself from the conventions of grammar and form but do words have the freedom to rave nonsense ? Is raving nonsense a means of speaking the truth or does the truth bleed into the words transforming language into a cauldron of raving nonsense and chaotic ramblings, without the freedom to express nonsensical ramblings writing loses its most fundamental freedom and writing itself also becomes transformed into a mere "tool"

Remains of Life is a particularly challenging text to read because it is written without any paragraph breaks and with very limited punctuation -- it is essentially a single, run-on stream-of-consciousness sentence, even as it incorporates dialogue and others' accounts and commentary. While not simply nonsense-raving, the word-flow is certainly also far from straightforward; appropriately, given the subject matter, it is not a comfortable read, but readers should be aware of its challenges -- merely finding a spot to interrupt one's reading (or then jump back in) is difficult, and at over three hundred pages it is no quick read, regardless how deeply one manages to immerse oneself in it.

The Musha Incident can be seen as a sort of last gasp uprising against the colonizer, long after the local Chinese population had essentially accepted it -- but Wu He warns about romanticizing that idea, considering events also in the context of the traditional headhunting rituals the tribes still practiced.

As he then also frequently notes, the afterwar period saw a continuing if different form of subjugation and colonization of the aboriginal tribes, the (Chinese) Taiwanese society the dominant cultural and political power, the 'White Terror' -- the martial law that lasted from 1949 to 1987 -- long limiting dissent. And so, for example, a local whom he asks about the tribal history notes:

The only thing that people of my generation think about is going out to the cities to make money, we've almost completely forgotten the traditional legacy that our ancestors have left us with, my father lived through the Musha Incident, he never says much about it, he keeps most of it inside

Wu He even begins his novel by reminding of the rapid recent modernization and transformation of Taiwan, noting that he had first heard of the Musha Incident when he was a teenager, and: "the economy of this island nation had yet to take off, there were still no McDonald's fast food restaurants". He removed himself from modernized, contemporary Taiwan previously, and his foray to Riverisle and into this subject-matter is another attempt to capture what is rapidly being lost and transformed.

Occasionally, he is almost resigned, facing that common problem of history:

I too have asked myself many times whether all my questions about "the Incident" were superfluous, after all history has already decided what its place is to be, the political has already lauded it with glory and honor

Yet Wu He's account shows the value of further engagement with the subject -- and, specifically, its present-day interpretations. So, for example, modern-day influences and the debate about them still reflect on the past ones:

"A little bit of new technology comes into the reservation, and before long we are destroyed, assimilated," Cuz-Hub said that he couldn't accept that, but he couldn't help but accept what was happening before his own eyes, "I'm not really willing to use words like 'invade' or 'assimilate,'" if we talk about invasion then we must also reflect upon why we didn't resist invasion, and if we talk about assimilation we must also ask ourselves why we didn't resist assimilation

Many of the names given to the characters are basically simply descriptive -- Deformo, Weirdo -- and a central figure in the novel is simply called Girl, a granddaughter of Mona Rudao, who led the 1930 assault. Girl contains many of the dichotomies is confronted with -- a seeker, too ("One day I'm going to set out in search of ..."), a local who has ventured out but also wishes to return to the historical, a tribal representative yet also influenced by the foreign (notably in constantly playing classical Western music, for example). In his brief Afterword Wu He notes that one of the main objects of the novel is to examine: "the Quest of Girl".

Yet the narrator is as much a central figure, and his own quests also at the heart of the novel -- the understanding and interpretation of 'the Incident' and its larger implications long beyond it, as well as his own struggles-as-writer. He expresses ambivalence about rebellion, even as he understands its important role both in history and society and in his own life and writing:

I began to grow rebellious during my teenage years, that rebelliousness continued and can even be seen in my writing today -- writing is itself a form of rebellion, I really despise endless rebellion [...] I know that there is a way to bring an end to this rebellion, but the key to resolving this issue lies not in suppressing rebellious actions, it lies in truly facing up to this thing called "dignity," those who rebel against something and those who fight to safeguard something are simply expressing two sides of teh same coin, what they both fight for is dignity

Wu He's narrative is an outpouring, and only to a limited extent a story; the fascinating historical events and his encounters do make for an often engaging read, and his efforts to consider both the Mushu Incident and its aftermaths are fascinating -- but it is not easy to get through. Too lively and varied to be a slog, Remains of Life also remains a frustratingly slippery text. - M.A.Orthofer

The Musha Incident is a dark moment in Taiwan’s colonial history (1895-1945), as well as a long-forgotten one. On 27 October 1930, the indigenous Atayal people decapitated 134 Japanese soldiers. Japanese revenge was brutal, bringing the Atayal tribe to the edge of extinction. Later, the Nationalist government labeled the Incident a heroic retaliation against Japanese invasion, but condemned the Atayal’s primal ritual of headhunting.

Taiwanese writer Wu He was not satisfied with this highly superficial and politicized discourse and determined to uncover the truth of this period of history and its legacy. The result is this novel. First published in 1999, Remains of Life was recently introduced to the English-speaking world by Dr Michael Berry, a professor of Modern Chinese literature and film at UCLA. Thoughtfully and insightfully, Berry has devoted his translation to maintaining the novel’s original experimental writing techniques. The entire book contains one single paragraph over the length of nearly 300 pages, with only a few sentence breaks, multiple names for each character, and stream of consciousness. Reading this novel is an intellectually challenging and rewarding process.

To answer critical questions on the margins between memory, imagination and interpretation, Wu He returned in 1997 and 1998 to the Atayal reservation, a small mountain town in central Taiwan, where the unrest started and continued. He interviewed and befriended the survivors of the Incident and their descendants. From these oral accounts, he determined that, seen from indigenous perspective, the Incident has an entirely different focus on freedom and dignity: for the Atayal, headhunting is less about violent resistance against Japanese colonization than a time-honored tradition and source of meaningful indigenous pride.

Wu He is not the first to use the Musha Incident as source material. Before Remains of Life, there have been a comic book, a movie, and another novel based on the Incident , not to mention numerous scholarly works. Wu He’s approach, though, is unique and innovative. His novel does not directly confront the bloodiness of the Musha Incident, but opens a space including fictional details, modernist thoughts, and alternative ways to understand history. As outlined in Wu He’s afterword, his text consists of three layers. The first is the legitimacy and accuracy behind the “Musha Incident” led by Mona Rudao, as well as the “Second Musha Incident”; second, the quest of Girl, the narrator’s Atayal neighbor who travels back and forth between the deep mountains and an urban lifestyle; and lastly, the remains of life, that he visited and observed while on the reservation, leaving its meaning an open question.

In this novel, the fractured narrative that integrates monologue and stream of consciousness pushes readers to question conventional historiography: How has history been told? Who has the authority to record and comment history? For example, the novel presents alternative opinions on Muna Rudao, the leader of the Musha Incident. While nationalist discourse constantly describes him as an anti-colonial hero, the Atayal people think that he was “a man of courage and insight”, resisting so-called civilization and defending a traditional way of life. Another voice comes from Mr Miyamoto, a pro-Japanese tribe member, who considers Muna Rudao less a hero because he misused his dignity to slaughter third-rate samurai. Wu He here argues that there is hardly any true independent history. The novel does not limit itself within memory. Wu He links the (de)mystified history of the Musha Incident to his doubt about modern-day assimilation. If it is an accepted rule that human history is always a linear development, what we would lose in this unavoidable progress? The novel challenges the assumption that a more advanced civilization is entitled to judge, change, or even eliminate, primitive civilizations in the name of modernization. The Japanese who slaughtered hundreds of the Atayal in the colonial period with modern military weapons could be regarded as being much more savage. The Nationalist government’s project to incorporate indigenous people is no less discriminating or destructing than the Japanese policies. They both labeled Atayal people and their traditions as being backward, and both led to environmental and moral devastation. According to the narrator, indigenous culture today has been repeatedly consumed for new political agendas. Wu He reveals that, from military invasion to capitalist exploitation, not only the Atayal are losing their population, language, belief, and lifestyle under the pressure of modernization and urbanization, but also abandoned by the rapid growth in Taiwan.

The novel mixes in events in the author’s real life, such as his military service and his reclusive life. In fact, the Atayal’s struggles of “the primitive to blend itself into civilization” reflects the author’s own identity crisis—his own frustration and anxiety as a male Han intellectual. Sometimes the narrator taunts his own culture, considering cursing a Chinese trait and referring to the privileged class in Taiwan as “male chauvinist Chinese pigs”. Yet at other times, he holds firm to Han ethics, including mixed feelings towards Atayal people’s worship of female reproduction. The narrator senses “the incredible charm and magnanimity of the primitive.” So while Girl expresses her joy with primal and natural sexual desire, the narrator ambiguously judges Atayal women according to the golden Han Chinese Rule of chastity, which he apparently takes it as an index of civilization. Hs is also ambivalent about Atayal-Japanese interracial marriage.

The novel presents a surprising degree of carnivalesque writing, featuring perhaps the most absurd and wild sexual fantasy in contemporary Chinese literature. The narrator is constantly obsessed with sexuality, conducting dull discussions comparing women’s bodies in Taiwan, Japan and America; or having tedious conversations with Girl on “missionary-style”. Girl’s body is treated as the metaphor for the fate of the tribe.

Although his Han Chinese identity determines that he is an outsider regarding the Musha Incident, the narrator, or the author Wu He, is ambitious enough to reexamine this period of history. Instead of attempting a monumental epic, Wu He picks up fragmented moments and the remains of life to reveal the never-healed scar of indigenous people in Taiwan, a society rich in multiculturalism and ethnic diversity. The very act of writing provides freedom from the oppressed sexualized body and social restrictions. The seemingly absurdity in the novel nonetheless reflects Wu He’s honesty and humility. - Yu Zhang

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.