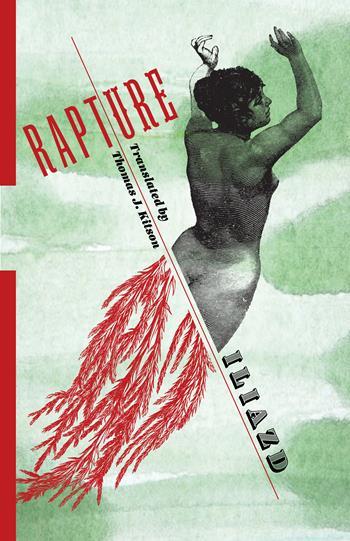

Iliazd, Rapture: A Novel, Trans. by Thomas J. Kitson, Columbia University Press; Tra edition (May 16, 2017)

The draft dodger Laurence yearns to take control of his destiny. Having fled to the highlands, he asserts his independence by committing a string of robberies and murders. Then he happens upon Ivlita, a beautiful young woman trapped in an intricately carved mahogany house. Laurence does not hesitate to take her as well. Determined to drape his young bride in jewels, he plots ever more daring heists. Yet when Laurence finds himself casting bombs alongside members of a revolutionary cell, he must again ask: is he a free man or a pawn of history? Rapture is a fast-paced adventure-romance and a literary treat of the highest order. With a deceptively light hand, Iliazd entertains questions that James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and Thomas Mann once faced. How does the individual balance freedom and necessity, love and death, creativity and sterility? What is the role of violence in human history and culture? How does language both comfort and fail us in our postwar, post-Christian world? Censored for decades in the Soviet Union, Rapture was nearly lost to Russian and Western audiences. This translation rescues Laurence's surreal journey from the oblivion he, too, faces as he tries to outrun fate.

Magical... like a wizard's spell. - Aleksandr Goldshtein

[An] absolutely peculiar world that engulfs the reader from the first line. - Boris Poplavsky

A closely guarded secret of Russian literature, the prose of Ilia Zdanevich, better known by his artistic pseudonym Iliazd, has never left the narrow coterie of literary connoisseurs. Censored in the USSR, thanks to the author's dissidence from the official Soviet ideology and aesthetic, and spurned by Russian émigrés because of his leftist politics and unapologetic stylistic and narrative experimentalism, Iliazd's work has been rediscovered only recently, challenging received wisdom about twentieth-century Russian literature and its place in transnational modernism. Now, for the first time, this rapturously narrated parable mythologizing the life of the Russian avant-garde is available to Anglophone readers. This tale of murder, kidnapping, passion, betrayal, treasure hunt, and political terrorism is set against the backdrop of a fantastic land inspired by the author's native Caucasus. The novelistic repertory of modernism grows richer and more diverse as Rapture joins contemporary French, Italian, and Anglo-American experiments pushing the limits of the genre. - Leonid Livak

The early 20th century was a time of great change and upheaval; it produced wars and revolutions, but also a great flowering of experimentation in the creative arts. The whole of Europe was affected, but a particularly distinctive strand was seen in Russia, and the avant garde in that country was known for its art, poetry and literature. The decades that came after saw the crushing of individuality and many writers, in particular, got lost in the repression; they’re still emerging from that obscurity nowadays, and a recent name to be added to that list is Ilia Zdanevich, known by the simple pseudonym Iliazd.

Iliazd (1894 –1975) came from an interesting time and place; born in Tbilisi, Georgia to Polish/Georgian parents, he studied Law in St. Petersburg and fell in with the avant garde art movements of the time. He worked with artists such as Goncharova and Larionov, as well as becoming involved in Futurism, Dada and surrealism. Leaving his home country and moving to France in the early 1920s, he reinvented himself, working through a career in writing and the visual arts, eventually becoming an innovator in typography and design. In fact, it’s for these latter two that he’s most remembered, so it’s fascinating to see his early experimental novel from 1930 make it into English for the first time.

Rapture tells the story of Laurence, a young man who escapes to the mountains to avoid being drafted. Here, his life takes a different turn, as he stumbles upon a penitent monk and murders him, for no real reason apart from the fact that the Brother annoys him. Laurence then takes up a life of crime, forming a band of brigands and demanding obeisance from the locals. And a strange lot these are, particularly a group of ‘wennies’ living in a village with a name no-one can pronounce and singing a song with words no-one can understand. However, a chance encounter with Ivlita, the beautiful daughter of a forester who lives in seclusion in a carved mahogany house, changes his course. He whisks Ivlita away, depositing her in the mountains, and makes for the big city to steal money and jewels with which to worship her. Here, he falls into a completely different milieu, becoming subordinated by Basilisk, a cold politico with hypnotic eyes; and the kind of crimes he undertakes are very different from simple theft. Will Laurence escape from the city and make it back to Ivlita and the mountains? Has Ivlita remained faithful? And what will the future bring for both of them?

And gradually it dawned on the young man that words were to blame for everything, and that words, which had raised him to the dignity of a bandit, were now standing guard over him and suffocating him, and he needed a new word to ward off failure, a spell that undoubtedly only the wenny knew and could teach.

That rather simplistic plot summary belies the complexity of Iliazd’s novel, which is brimming with imagery, allusion and fantastic elements. Angels appear, dead monks seem to come back to life, nature itself is a living entity. These rather spellbinding effects appear throughout the sections of the book set in the flatland or the highland; by contrast, the city is portrayed as a very different place, full of the contradictions between rich and poor, glamour and degradation.

In fact, contrasts abound throughout the book: the clash between city and country; the differences between the highlanders and the flatlanders; the ugliness of the wennies compared with the beauty of Ivlita. The difference between Basilisk and Laurence is striking, and the latter is very much out of his depth when dealing with the educated city men; this could be read as a comment on how easily the ‘simple folk’ were influenced by the professional revolutionaries during the fall of the Romanov dynasty. But Iliazd has no time for the ruling classes either, with the emperor being portrayed as an idiot, controlled and manipulated by the secret police who create plots and assassinations for their own ends.

Rapture is an intriguing, complex work, with odd experimental touches (for example, there are no full stops at all at the end of paragraphs). The mix of two very different settings is fascinating although at times I felt the two locations did not sit altogether comfortably together. The book, however, did seem to me to draw on earlier works and authors; the village sections, with the cretins singing mindlessly and the credulous and shifty locals, brought to mind Saltykov-Shchedrin’s satires; whilst the political shenanigans and assassination attempts were reminiscent of Bely’s Petersburg or Conrad’s The Secret Agent. Basilisk in particular is a cleverly-named and sinister character, manipulating Laurence from behind the scenes; and there is ambiguity about his final fate (like much in this book!) as it is unclear whether what Laurence thinks happened to Basilisk actually did or whether it’s imaginary. The book does suffer a little in that it reflects the usual unsatisfactory attitude to women that prevailed in so many of the avant garde movements of the early 20th century; we are back to the Madonna-whore cliché and Ivlita has to either be pure or a slut, which is a shame.

But Rapture really is a mixture of slapstick and philosophy; it abounds with scatological references (truly, the author seems to have had a thing about excrement and the obscene!) and the translator must have had great fun rendering them into the vernacular. The language is dazzling, the action picaresque, but beneath the surface Rapture asks a lot of questions. The concept of rapture itself, which seems to be fleeting and necessary and after which the characters seem to be chasing, is somewhat undefined and is different for each person; for example, Ivlita seems only really happy when communing with nature. Laurence is torn between his obsession with Ivlita and his desire for freedom. And religion seems no real answer, nor does politics so I ended up thinking we might all be happier singing mindless songs like the wennies!

Translator Kitson provides an excellent introduction which discusses Iliazd’s life, as well as putting this book into the context of his times and surroundings, whilst discussing its deeper meanings. According to him, it contains many sly portrayals of key figures in the various movements to which Iliazd belonged, although I confess I didn’t pick these up. I don’t think that matters, however; as what is here is an adventurous, experimental and thought-provoking novel which most definitely deserves more attention than it’s received over the years. - Karen Langley

Who is Iliazd? It will most likely be the first question asked when anyone comes across Rapture, “the first complete literary work by Iliazd available in English.” Iliazd is the pseudonym of Ilia Zdanevich (1894–1975), a Russian writer/typographer who hung around Paris in the early 20th century, drifting in and out of some of the Modernist period’s most significant circles — Futurism, Dadaism, Cubism, Surrealism, even Coco Chanel. While not on the same activist level as Gertrude Stein (or Carl Van Vechten in Harlem), he was a sort of avant-garde jack-of-all-trades: his little black book must have been a who’s who of significant artists. Aided and abetted by Columbia University Press’s Russian Library, Thomas J. Kitson has come up with a fascinating translation of Iliazd’s first novel, Rapture, an eccentric volume that will hopefully bring some welcome attention to this obscure literary figure.

Iliazd took up art and poetry during World War I, a time when progressive artists in Russia and Europe were thrown into a panic. The chaotic conflict suggested that either nothing meant anything anymore, or it was up to artists to reinvent a meaningful world based on new principles. Manifestos were the rage, and Iliazd spent much of his early creative life in Russia penning Futurist tracts and taking part in public debates about the direction of art and poetry. His ambitions brought him to Paris in 1921, where, along with his writings, he began concocting livre d’artiste These elaborate volumes — made in collaboration with the likes of Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, and Joan Miro — made his reputation in the decades to come.

His prose pieces, written during the ’20s and ’30s, have been overlooked. Rapture was the only novel of his published during his lifetime (in 1930 under his own imprint 41°). The manuscript was rejected by every publishing house in Russia — it was deemed offensive to the ideological tastes of the day, and mostly ignored by those that mattered in France. In a move that harkens back to the PR of the Parisian Dada scene, Iliazd slipped notes into copies of his novel in the only Parisian bookstore that carried it. His words to prospective buyers: “Russian booksellers refuse to sell this book. If you’re that inhibited, don’t read it!”

In one sense, Rapture is a daredevil novel. Murder, romance, betrayal, and treasure hunting push the fast-paced, helter-skelter narrative forward. Laurence is a deserter from the army who demands that he shape his destiny. His quest for independence takes the form of banditry in a mountainous dreamscape based on Iliazd’s childhood home in the Caucasus. He terrorizes the countryside, robbing and pillaging, but somehow leaves the traditional society of peasants, hunters, and loggers unruffled. Laurence comes across the ethereal Ivlita, the daughter of a former forestry administrator who has lost his mind. She has been trapped in her father’s house (built of ornately carved mahogany), reading the books in the library and communing (at least indirectly) with nature. Laurence is eventually propelled by political turmoil, and his devotion to Ivlita, to move his illegal operations into the lowland cities. His need for plunder leads to ever more dangerous and elaborate heists, often involving people he does not know or trust, including a parodic revolutionary cell who want to score big in order to fund their movement.

Of course, Rapture is more than a parody of the picturesque adventure genre; it represents Iliazd’s declaration of personal transformation, an announcement that the next stage in his metamorphosis was on its way. Kitson writes in his preface that the novel is a kind of roman a clef, Iliazd’s way of “reckoning with the Russian avant-garde.” It is his ambivalent farewell to Futurism, an evocation of the dynamism of this “furiously creative” period. Figures such as Larionov, Mayakovsky, Goncharova, Kruchenykh, and Burliuk are found in disguised form in the narrative, but it is not necessary to have a PhD in Russian Literature to enjoy this book.

The result is a kind of impish experimentalism. Iliazd eschews time and space; the novel’s setting is never made clear. A village is referred to as “the hamlet with the incredibly long and difficult name.” A particularly “goitrous, or wenny” family lives and sings songs of weird unintelligibility, similar to the Joycean neologisms in Finnegans Wake. This and other examples of linguistic slapstick is a nod to the Futurist technique of ‘beyonsense.’

Rapture also raises philosophical questions about perspective, discouraging us from identifying with any particular character. In the beginning, when a wandering monk gets caught up in an unlikely snow storm in a fantastical landscape, there are “Voices added to voices, unlike anything recognizable… Occasionally, they tried to pass for human, but ineptly–so all this was obviously a contrivance. Someone started romping on the heights, pushing down snow.” Iliazd’s characters are subject to a cruel, capricious Writer/God, the victims of a kind of sadistic black comedian whose imagination anticipates the pratfalls of postmodern humor. Underneath the hijinks is a serious intent: to mangle fiction and language in ways that raise primal questions about the value of realism, naturalism, even economics.

This unruliness will undoubtedly be frustrating for some. Inexplicability abounds. Ambitions and desires are discarded the moment they are achieved. The relentless illogic of Rapture undercuts all human activity (art included), seeing it as “an attempt made with unsuitable means.” One of Iliazd’s mantras serves as the strongest counter to the book’s implacable pessimism: “A poet’s best fate is to be forgotten”; sometime in the future someone will understand the value of Iliazd’s early stab at deconstruction.

Perhaps more decades need to pass; Iliazd is not in the same league as James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. In Rapture he comes across as kind of Modernist bellwether reflecting (rather than mastering) the yen for iconoclasm that was energizing European bohemians at the time, the call for the radicalization of life, psychology, literature, art, and politics. Still, the novel is a worthwhile curio (a minor classic of Modernist literature, perhaps) that grapples, entertainingly, with the era’s artistic, structural, and revolutionary quandaries. Rapture does not upset conventional views of the Modernist period, but it is pretty interesting to look at — another facet on the gem. - Lucas Spiro

In March 1913 a young man started a riot in a Moscow theatre with an American shoe. During his lecture, ‘On Futurism’, Ilia Zdanevich, an eighteen-year-old student from Tiblisi, Georgia, held up a Vera brand shoe before his audience and tauntingly claimed that it was more beautiful than the Venus de Milo because it could literally raise people above the filth of the earth. This combination of Russian nihilism – one of Dostoevsky’s characters famously remarks that a shoe is worth more than Pushkin or Shakespeare – with Marinetti’s worship of technology so incensed the audience that they attacked the speaker. The ensuing melee so badly damaged the theatre that Zdanevich had to forfeit his fees. The incident established his reputation as a provocateur and theorist, and was symptomatic of the kinds of extreme reactions Modernist art was provoking from audiences: two months later the premiere in Paris of Stravinsky’s ballet, The Rite of Spring produced a similarly violent response.

Over the next few years it may have appeared that Zdanevich was content with his role as an aesthetic propagandist. He continued to espouse Dada-esque manifestoes, notably the Everythingist manifesto, which advocated borrowing techniques from wildly different genres and styles, with the aim of being liberated from either current or previous artistic conventions. According to this view the ‘fullness’, rather than the coherence of a work of art was what mattered. What he didn’t seem inclined to do was risk putting any of this grand theory into practice by producing art. Not that anyone could accuse Zdanevich of being a dilettante: in 1916 he was a war correspondent in eastern Anatolia, while the following year he worked on an archaeological dig in Georgia. After the October

Revolution he was still giving lectures –intriguing ones, judging by

some of their titles: ‘On the Magnetism of Letters’, ‘Orthography and Straining’ and ‘Tyutchev, Singer of Shit.’ However, by this point Zdanevich was also writing zaum poetry, an experimental form whose sounds lacked discernible meaning yet were still supposed to be profound, not so much nonsense as ‘beyonsense.’

If Zdanevich had remained in the Soviet Union it’s likely that his work would have been proscribed, as happened to most other avant garde writers (though even the champions of Soviet realism might have struggled to identify counter-revolutionary messages in beyonsense). An intimation of this made him leave in 1920, telling people it was too hard to make pure art free from politics. He spent a year in Istanbul waiting for a French visa, and arrived in Paris in 1921, where, in what seems a highly symbolic act, he rechristened himself as ‘Iliazd,’ a combination of parts of his first name and surname. But there were also strong continuities with his life in Moscow. ‘Iliazd’ continued giving lectures and readings and unsurprisingly found common cause with the Dadaists. In 1923 he organised a Dadaist soiree that also ended in a punch up, but on that occasion it was a matter of Dadaist rivalries, rather than the audience’s fury. The fact that in 1928 he tried to publish a novel in Russia also suggests he hadn’t entirely cut ties with his former life. But he couldn’t have picked a worse time to do so – publishers were being shut down and their editors arrested as ‘Trotskyists.’ Iliazd’s novel was unanimously rejected. In 1930 Iliazd self-published the novel in Paris (which he funded by working as a designer for Coco Chanel). Even there he faced obstacles – only one store agreed to stock the book because of its ‘obscenities.’ He found much greater success making beautifully designed livres d-’artiste (artists’s books) with Picasso, Miro Ernst and Giacometti from the late 1930s on. It’s said that in the mid 1970s he could be seen wandering round Paris’s Latin Quarter wearing a sheepskin coat, herding a flock of cats before him.

Given Iliazd’s career as a poet and theorist, one might expect his 1930 novel Rapture to be a formally and linguistically challenging novel, a sort of Finnegan’s Wake with shades of early Le Clézio. Instead it’s a fast-paced, mordantly funny yarn that borrows from (and subverts) the adventure genre.

A lot happens in this book. There are stabbings, shootings, heists, betrayals, murders of every kind. There are blizzards, drunken wakes, hunts of epic carnage after which ‘the slaughtered beasts showed black from afar, a magnificent hill.’ Though the action of the novel is generally realistic, at moments it scales successive peaks of fantasy, as when a snow white archangel descends, blowing a trumpet, after which ‘a sloth of bears issued toward the cemetery’ where they ‘settled back on their paws, and begged alms.’

At the epicentre of this chaos is Laurence, an apparently likeable, modest, fun-loving draft-dodger whose criminal career moves swiftly to murder then banditry (followed by

lots more murder). Laurence himself doesn’t appear until the middle of the third chapter; the book instead begins with an account of the perilous peregrinations of a monk, Brother Mocius, through the mountains, during which he drinks brandy, masturbates, and nearly dies several times. While this is frequently presented as a spiritual test, Iliazd also constantly undermines the elevated gravity of these moments with interjections of uncertainty:

lots more murder). Laurence himself doesn’t appear until the middle of the third chapter; the book instead begins with an account of the perilous peregrinations of a monk, Brother Mocius, through the mountains, during which he drinks brandy, masturbates, and nearly dies several times. While this is frequently presented as a spiritual test, Iliazd also constantly undermines the elevated gravity of these moments with interjections of uncertainty: Finally, trumpets sounded. The winds broke free of the surrounding ridges and diving into the valley, beat about fiercely, but you couldn’t tell why. On the right, unclean spirits made the most of the disarray by sending up an infernal roar, and from behind, something like violins or the whine of an infant in pain barely bled through the tempest. Voices added to voices, unlike anything recognizable, more often that not. Occasionally, they tried to pass for human, but ineptly—so all this was obviously a contrivance. Someone started romping on the heights, pushing down snow

Though playful, this introduces one of the main themes of the novel – that nothing is ever what it seems, or rather, that nothing is stable, no thought, state or feeling can last. Its characters (like all of us) repeatedly fail to grasp ‘the phantom of constancy.’ Instead everything is in a state of ceaseless transformation, as Ivlita, a forester’s daughter, observes during a lovely moment of pantheistic rapture:

She already saw that trees were not trees, but souls who had passed their way in earthly form and were passing it now in the guise of trees. It turns out that trees advance, cliffs migrate, the snowy veil undulates.

Though Rapture is full of spirits and angels it doesn’t occupy any consistent ontological position, as illustrated by the view of Ivlita’s father who is ‘neither a believer nor an unbeliever and thought there were neither angels (evil or good) nor miracles; everything is natural or normal, but there are, so to speak unusual immaterial objects we know nothing about since, for now generally speaking, we don’t know anything.’

Though Rapture is full of spirits and angels it doesn’t occupy any consistent ontological position, as illustrated by the view of Ivlita’s father who is ‘neither a believer nor an unbeliever and thought there were neither angels (evil or good) nor miracles; everything is natural or normal, but there are, so to speak unusual immaterial objects we know nothing about since, for now generally speaking, we don’t know anything.’Rapture perfectly embodies Iliazd’s idea of fullness despite contradiction. Even simple statements about character are quickly refuted, often in the same sentence. An old man who has ‘irrevocably lost his mind’ is then described as ‘the wisest shepherd.’ His wife is said to be ‘well-preserved and beautiful, despite her monstrous goiter and hunchback.’ The novel doesn’t claim that there’s no such thing as truth – just that we can’t know it. Truths are compared to treasures which ‘really did exist, but only so long as they went unclaimed. Find them, and they’d crumble to dust.’

Even at the level of punctuation there is no certainty; none of the paragraphs in the novel end with a period. Perhaps this is meant to suggest that all meaning must eventually dissolve into the white abyss of the page. This, at least, is Brother Mocius’s fate. At the end of the first chapter a stranger (who we later learn is Laurence) appears and throws him off a precipice.

Laurence’s explanation for why he kills the monk echoes that of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment – it’s a rational and impulsive act that is an expression of his free will. Later in the novel he kills a sailor on a similar whim, and has no qualms about other murders. The novel matter-of-factly relates that for him ‘Eliminating the watchmen, his wife, and his small daughter was easy.’ Yet in his own mind Laurence has a moral code. He believes that a murder committed freely is acceptable unlike a murder committed under compulsion (for example as a soldier). Apparently, ‘murder is the only way to make freedom visible.’

Amongst the highlanders Laurence’s moral calculations aren’t challenged. In the village which has an unprounceable name (even for its inhabitants) only funerals inspire real celebrations. The general view there is that ‘Murder itself was nonsense; who hadn’t, one might ask, had occasion to murder?’ When Ivlita and Laurence become lovers she also tries to convince herself that she doesn’t mind his violence, because ‘bear law was no worse than human law.’ As the body count of the novel increases, Ivliita and Laurence’s relationship becomes increasingly strained, as does her reasoning to excuse his behaviour. Eventually she tries to pretend that what is unambiguously bad is in fact its opposite, so that rather than ‘condemning evil, she found in it the most profound manifestation of good order and human uplift.’

The first major challenge to Laurence’s worldview comes from a Marxist group of robbers who strive to make ‘everyone equally poor.’ They supply Laurence with ‘the means of production’ (soldiers and dynamite) and engage him in dialectical reasoning, telling him ‘You seek freedom, but necessity propels you, the party strives for what is necessary and is therefore free.’ According to them, Laurence isn’t free because he has made death a kind of commerce. Eventually Laurence realises he’s logically trapped between being immoral and free, or innocent yet controlled:

had he really been killing just to kill, proving that freedom exists? But that meant there was no confusion , and those who suspected a boundlessly ill will in Brother Mocius’ murder had been right, and Laurence was, in fact, an evil man. At the same time, Laurence knew he was no villain, and he was sure that if paradise existed, space would be found there even for him. Then what was he? A plaything of the elements?

But as the novel gleefully stresses, there is a way out of this philosophical bind. Death is the only state of perfection, the only solid fact. Souls ‘all go on living, not their own life, but their death, their freedom from the empty human way of life.’ Iliazd compares life to a swoon, and laments that ‘Alas, if choice exists, that means death is not yet, and the swoon is not over. Oh, to regain consciousness.’ Free will is thus an imperfect state, a kind of dreamed delusion. Only after death do we wake.

Iliazd once claimed that a poet’s best fate is to be forgotten, but while this novel has taken a long time to find a new audience, there’s nothing musty about Thomas J. Kitson’s excellent translation, which makes the prose of the book seem fresh. Though the novel offers few philosophical consolations, there’s an air of celebratory defiance to the way it offers its bleak pronouncements, from which a reader, if so inclined, might conclude, à la Sartre, that art and its attendant raptures is another way to escape the swoon of life. As Iliazd said in a lecture in 1921, ‘reason is mendacious, poetry is immaculate and we, too, are immaculate when we are alone with it.’ - Nick Holdstock

Rapture is an odd novel, a sort of adventure tale that takes on (and in) mythical proportions (and elements), set in a faraway no-place (much of it in a hamlet with an: "incredibly long and difficult name, so difficult even its inhabitants couldn't pronounce it") that is clearly modeled on the Caucasus. It is a novel of an indeterminate time but can easily pass for the lawless 1920s, with the Soviet Union slowly encroaching -- an unnamed political party figures prominently in trying to shape the political future here -- but the outback still out of the reach and control of centralized powers and a world unto its own. The novel begins with a Brother Mocius, journeying, as he often did, in the harsh local conditions. Brother Mocius escapes a natural death but not an unnatural one -- tossed, rather than falling, into the abyss. His death and and bizarrely sensational burial ("the believers pried the corpse from its coffin, filled the coffin with brandy, and, down on all fours, slurped it straight from the coffin", among other things) shake things up in this out-of-the-way (and set-in-its-own-(unusual-)ways) area. (As it turns out, Brother Mocius surprisingly goes on to shake things up elsewhere, too.)

The central figure, however, is one Laurence, a worker at the local mill who had been hiding in the woods to evade a visiting draft commission. He isn't much liked at his workplace and has no friends, but he's a successful type -- "everywhere and always he was inevitably the hero". His arguably impetuous actions force him to flee even further from civilization, and he finds a haven with a local goitrous family -- 'wennies'. He also comes across the bewitching Ivlita -- "an altogether exceptional phenomenon" -- raised in comfortable isolation, and: "short on rapture".

Laurence adopts the role of bandit -- a local overlord, who also strikes out with his band of wennies. There are road-adventures -- attempted heists, including a daring one of a train, as well as ones with larger political implications, with Laurence sensing he is being used as a pawn -- while there is always the beautiful Ivlita to draw Laurence back.

It is a chaotic world -- with pockets of exception, as, for example:

Ivlita knew now that there was no disorder in the world and that everything was confiend in a perfect structure

Laurence and Ivlita's union is not a happy love story of larger than life figure, and her pregnancy not the joyous culmination of their fates. Their combative relationship, and the story, doesn't have a happy end -- just the one they were fated for.

Rapture is both traditional regional adventure tale -- adapted for and reflecting its times -- and experimental fiction, Iliazd taking liberties with story, style, and language. In upending -- in a variety of ways, no less -- readers' expectations, Iliazd's variation on this kind of tale offers very different satisfactions. A vivid, often comic, and always harsh story it veers between exciting pulp and much more ambitious mythifying near-poetry; it's also almost surprisingly accessible -- and a fun, if twisted, read.

Rapture also comes with a thorough, fairly lengthy (over forty-page) Introduction by the Translator -- apparently deemed necessary to provide background about an author who (in this context) is almost entirely unknown as well as to situate the novel in its time, place, and the circumstances around it. All this is useful, in a way, but can also be a distraction -- the novel, like any decent fiction, stands up perfectly well all on its own. - M.A.Orthofer

Thomas Kitson on a Neglected Gem of Russian Modernism

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.