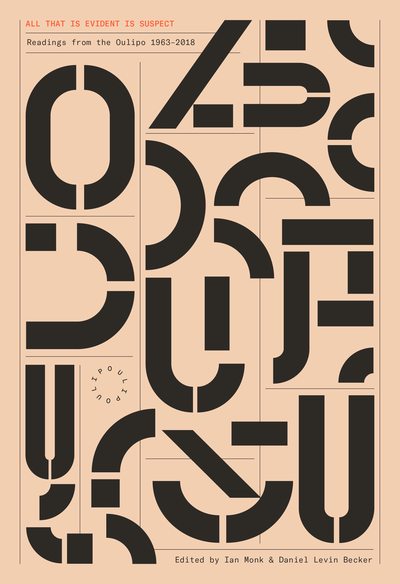

All That Is Evident Is Suspect: Readings from the Oulipo 1963-2018, Ed. by Ian Monk & Daniel Levin Becker, McSweeney's, 2018.

Since its inception in Paris in 1960, the OuLiPo―ouvroir de littérature potentielle, or workshop for potential literature―has continually expanded our sense of what writing can do. It’s produced, among many other marvels, a detective novel without the letter e (and a sequel of sorts without a, i, o, u, or y); an epic poem structured by the Parisian métro system; a story in the form of a tarot reading; a poetry book in the form of a game of go; and a suite of sonnets that would take almost 200 million years to read completely.

Lovers of literature are likely familiar with the novels of the best-known Oulipians―Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, Harry Mathews, Raymond Queneau―and perhaps even the small number of texts available in English on the group, including Warren Motte’s Oulipo: A Primer of Potential Literature and Daniel Levin Becker’s Many Subtle Channels: In Praise of Potential Literature. But the actual work of the group in its full, radiant collectivity has never before been showcased in English. (“The State of Constraint,” a dossier in issue 22 of McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, comes closest.)

Enter All That is Evident is Suspect: the first collection in English to offer a life-size picture of the group in its historical and contemporary incarnations, and the first in any language to represent all of its members (numbering 41 as of April 2018 ). Combining fiction, poetry, essays and lectures, and never-published internal correspondence―along with the acrobatically constrained writing and complexly structured narratives that have become synonymous with oulipian practice―this volume shows a unique group of thinkers and artists at work and at play, meditating on and subverting the facts of life, love, and the group itself. It’s an unprecedentedly intimate and comprehensive glimpse at the breadth and diversity of one of world literature’s most vital, adventurous presences.

DISCUSSED: Sharks as poets and vice versa, the Brisbane pitch drop experiment, novel classifications for real or imaginary libraries, the monumental sadness of difficult loves, the obsolescence of the novel, the symbolic significance of the cup-and-ball game, holiday closures across the Francophone world, what happens at Fahrenheit 452, Warren G. Harding’s dark night of the soul, Marcel Duchamp’s imperviousness to conventional spacetime laws, bilingual palindromes, cartoon eodermdromes, oscillating poems, métro poems, metric poems, literary madness, straw cultivation.

Contributors include:

Noël Arnaud

Michèle Audin

Valérie Beaudouin

Marcel Bénabou

Jacques Bens

Claude Berge

Eduardo Berti

André Blavier

Paul Braffort

Italo Calvino

François Caradec

Bernard Cerquiglini

Ross Chambers

Stanley Chapman

Marcel Duchamp

Jacques Duchateau

Luc Étienne

Frédéric Forte

Paul Fournel

Anne F. Garréta

Michelle Grangaud

Jacques Jouet

Latis

François Le Lionnais

Hervé Le Tellier

Étienne Lécroart

Jean Lescure

Daniel Levin Becker

Pablo Martín Sánchez

Harry Mathews

Clémentine Mélois

Michèle Métail

Ian Monk

Oskar Pastior

Georges Perec

Raymond Queneau

Jean Queval

Pierre Rosenstiehl

Jacques Roubaud

Olivier Salon

Albert-Marie Schmidt

The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (‘Oulipo’) was created in Paris in November 1960 by François Le Lionnais and Raymond Queneau. The Oulipo would seek out, according to Raymond Queneau, “new forms and structures that may be used by writers in any way they see fit.” The application of mathematics and the sciences to literature, more specifically formal constraints, is used to liberate the writer’s creativity.

There are (or have been) forty -two members of the Oulipo, some are deceased, and the newly published collection ‘All That Is Evident Is Suspect: Readings from the Oulipo 1963-2018’, contains works by every member to date. The book contains fifty-four pieces, one co-authored.

The book opens with a short work by founder Raymond Queneau himself, undated and titled “Slept Cried” (translated by Ian Monk), it is a single page “elliptical evocation of the whole of existence”, a pertinent way to open the collection;

Started this diary today: desirous as I am to note down my first impressions. Unpleasant.

Hot milk, as they call it is disgusting: not nearly as good as amniotic fluid.

Having been washed and rubbed down, here I am still blind, back in my crib. Very interesting.

Slept twenty hours. Cried four. I quite clearly am not taking to hot milk.

I also pooed: in my linen.

To close the piece, after an “interruption of seventy-four years”, the diary is revisited. Is the Oulipo “extremely tired”?

As per any collection from a variety of writers this book is uneven at times, some pieces feeling clunky in their construction, this could be as a result of the translation as a constraint in French would be difficult to translate into English using the same constraint (for example, the piece “Invisible Cities: Lille” by Olivier Salon (translated by Ian Monk), “is a lipogram variant called a bivocalism: like the city’s name (Lille), it contains no vowels besides E and I.”)

Having said that the vast majority of the collection is very readable, stimulating and intriguing.

The piece by Italo Calvino “How I Wrote One of My Books” (translated by Iain White) “outlines the algorithm governing the interchapter narrative in his 1979 novel ‘If on a winter’s night a traveller’. Calvino stipulated that the explanation was never to be published in Italian.” Having read Calvino’s book twice before I now feel the need to revisit it for a third time given the complex algorithm in play.

I have previously referred to two pieces, from this book, regarding the structure of Georges Perec’s ‘Life A User’s Manual’ however the collection is not simply explanations as to the constraints used by the writers in other works, in fact these are minimal, generally consigned to the short explanatory paragraph accompanying each piece.

Some personal highlights, Latis’ “The Atheist Organist” (translated by Daniel Levin Becker) a small sample of his novel that contains “seven prefaces, a preface to those prefaces, a post-face, a postlude and no actual novel.” Jacques Bens “How to Tell a Story” (translated by Daniel Levin Becker), a short story taken from ‘Nouvelles désenchantées’ a collection that was awarded the 1990 Prix Goncourt de la Novelle (the award for short stories).

On Tuesday, April 25, 1989 – which was the Feast of Saint Mark, one of the four evangelists and, accordingly, one of the patron saints of writers – at around ten past two, a student in the sixth grade at the Collège Saint-Jean raised her hand and asked:

“How does one go about telling a story?”

Matthew had not been expecting this.

“Which story?” he said.

“I don’t know, just a story!”

“Well, that’s just it, you need to know, because not all stories are told in the same way. Look, let’s take the first idea that comes into your mind. It might be about a situation, or about a character. The story would develop differently depending on which. And usually you have both at the same time, because it’s rare to have one without the other. Then you have to give your hero a name, which is always sort of complicated. What’s your name?”

“Poems of the Paris Metro” by Jacques Jouet (translated by Ian Monk), fifteen and a half hours in the creation it was written covering every station in the Paris Metro, where the first line is composed mentally between the first two stations, it is then written down when the train stops at the second station, and so on. Stanza breaks are made when you change train lines, the work was based on graph theorist Pierre Rosenstiehl’s “Frieze of the Paris Métro”, a piece where he planned out the journey, so Jacques Jouet could write his exhaustive poem. Here’s the first few lines;

If governing, governing the coming hours, is more a matter of surprising myself than planning ahead,

the first few minutes have already rather put me out.

I have more than enough time to explain why.

Outside, I had hoped for slight rain so as to enter into the concept of shelter,

keeping a slight wetness, on the backs of my hands, for my thirst,

but this night at 5:30 a.m. was dry and mild and black like a black dress lit up from inside

by a body standing up in its fullness.

Jacques Jouet’s other contribution, “The Republic of Beau-Locks” (also translated by Ian Monk), is the first book in an ongoing serial novel, one I now need to hunt down.

Seven novel outlines by Paul Fournel, retells the same story from seven different perspectives, the piece translated by Daniel Levin Becker, it is playful and although a repetition the narrative shifts dramatically, voices include a parrot and a bunch of flowers.

Anne F. Garréta’s “N-evol” (translated by Daniel Levin Becker) opens with a set of six “givens”, starting with “1. the obsolescence of the novel, its inadequacy to everything a subject today might live, observe, experience, and think; 2. The boredom provoked in me by reading a “contemporary” novel;” the piece then observes various activities in nightclubs, toilets, using the voice of the DJ (sound familiar to readers of Garréta’s “Sphinx”?).

There is a very moving graphic piece by Étienne Lécroat (translated by Matt Madden), “Counting on You”, an homage to Lécroat’s sister who died just before her fiftieth birthday, it commences with a panel containing fifty words and a drawing with fifty strokes, then moves to a panel with forty-nine words and a drawing with forty-nine strokes and so forth until an empty final panel. A beautiful homage indeed.

Other notable, enjoyable pieces are Jacques Roubaud’s “Arrangements” part of his ‘Great Fire of London” project, this piece using 111,111 characters, Bernard Cerquiglini’s collection of emails presented as “A Very Busy Year”, Daniel Levin Becker’s “Writer’s Block” a consideration of a concrete sculpture using 999 words to ask 99 questions, the contemplation of a wordless poem by Marcel Bénabou, and Eduardo Berti & Pablo Martín Sánchez’s absurd “Microfictions”.

Overall the work is a wonderful introduction to forty-two different writers all using constraints within their work, and a great starting point for readers who are interested in the works of the Oulipo. An extensive coverage of the styles and types of works and one whereby you can have a taste of a writer before delving further into their work. If you want to add something a little different, something experimental and thought provoking to your library, look no further.

https://messybooker.wordpress.com/2019/01/08/all-that-is-evident-is-suspect-readings-from-the-oulipo-1963-2018-edited-by-ian-monk-daniel-levin-becker/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.