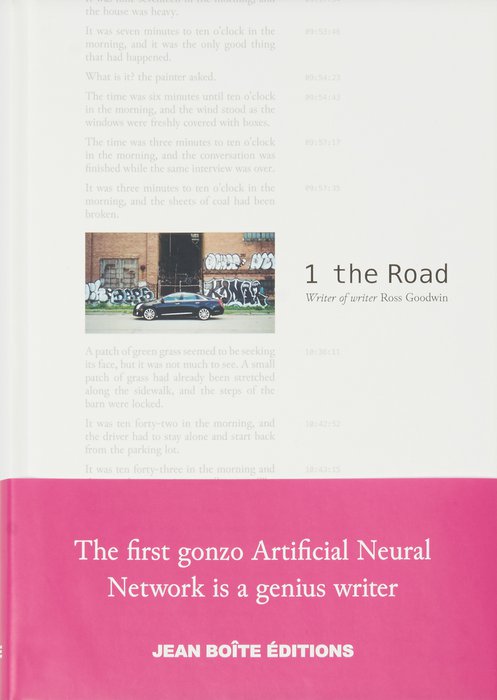

Ross Goodwin, 1 the Road, Jean Boite, 2018.

https://rossgoodwin.com/

1 the Road is a book written using a car as a pen.

Ross Goodwin is not a poet. As a prominent Artificial Intelligence creator, he outfitted a Cadillac car with a surveillance camera, a GPS unit, a microphone and a clock, all connected to a portable AI writing machine that fed from these input data in real time.

Together, they traveled from New York to New Orleans, in an experimental automation of the American literary road trip. As they drove, a manuscript emerged line by line from the machine’s printer on long scrolls of receipt paper that filled the car’s rear seats over the course of their journey.

1 the Road offers the first real book written by an AI, which captures us from the first page, when the journey begins:

“It was seven minutes to ten o’clock in the morning, and it was the only good thing that had happened.”

Rooted in the traditions of American literature, gonzo journalism, and the latest research in artificial neural networks, 1 the Road imposes a new reflexion on the place and authority of the author in a new era of machines.

“It was seven minutes to ten o’clock in the morning, and it was the only good thing that had happened.”

Rooted in the traditions of American literature, gonzo journalism, and the latest research in artificial neural networks, 1 the Road imposes a new reflexion on the place and authority of the author in a new era of machines.

Last year, a novelist went on a road trip across the USA. The trip was an attempt to emulate Jack Kerouac—to go out on the road and find something essential to write about in the experience. There is, however, a key difference between this writer and anyone else talking your ear off in the bar. This writer is just a microphone, a GPS, and a camera hooked up to a laptop and a whole bunch of linear algebra.

People who are optimistic that artificial intelligence and machine learning won’t put us all out of a job say that human ingenuity and creativity will be difficult to imitate. The classic argument is that, just as machines freed us from repetitive manual tasks, machine learning will free us from repetitive intellectual tasks.

This leaves us free to spend more time on the rewarding aspects of our work, pursuing creative hobbies, spending time with loved ones, and generally being human.

In this worldview, creative works like a great novel or symphony, and the emotions they evoke, cannot be reduced to lines of code. Humans retain a dimension of superiority over algorithms.

But is creativity a fundamentally human phenomenon? Or can it be learned by machines?

And if they learn to understand us better than we understand ourselves, could the great AI novel—tailored, of course, to your own predispositions in fiction—be the best you’ll ever read?Maybe Not a Beach Read

This is the futurist’s view, of course. The reality, as the jury-rigged contraption in Ross Goodwin’s Cadillac for that road trip can attest, is some way off.

“This is very much an imperfect document, a rapid prototyping project. The output isn’t perfect. I don’t think it’s a human novel, or anywhere near it,” Goodwin said of the novel that his machine created. 1 The Road is currently marketed as the first novel written by AI.

Once the neural network has been trained, it can generate any length of text that the author desires, either at random or working from a specific seed word or phrase. Goodwin used the sights and sounds of the road trip to provide these seeds: the novel is written one sentence at a time, based on images, locations, dialogue from the microphone, and even the computer’s own internal clock.

The results are… mixed.

The novel begins suitably enough, quoting the time: “It was nine seventeen in the morning, and the house was heavy.” Descriptions of locations begin according to the Foursquare dataset fed into the algorithm, but rapidly veer off into the weeds, becoming surreal. While experimentation in literature is a wonderful thing, repeatedly quoting longitude and latitude coordinates verbatim is unlikely to win anyone the Booker Prize.

Data In, Art Out?

Neural networks as creative agents have some advantages. They excel at being trained on large datasets, identifying the patterns in those datasets, and producing output that follows those same rules. Music inspired by or written by AI has become a growing subgenre—there’s even a pop album by human-machine collaborators called the Songularity.

A neural network can “listen to” all of Bach and Mozart in hours, and train itself on the works of Shakespeare to produce passable pseudo-Bard. The idea of artificial creativity has become so widespread that there’s even a meme format about forcibly training neural network ‘bots’ on human writing samples, with hilarious consequences—although the best joke was undoubtedly human in origin.

The AI that roamed from New York to New Orleans was an LSTM (long short-term memory) neural net. By default, information contained in individual neurons is preserved, and only small parts can be “forgotten” or “learned” in an individual timestep, rather than neurons being entirely overwritten.

The LSTM architecture performs better than previous recurrent neural networks at tasks such as handwriting and speech recognition. The neural net—and its programmer—looked further in search of literary influences, ingesting 60 million words (360 MB) of raw literature according to Goodwin’s recipe: one third poetry, one third science fiction, and one third “bleak” literature.

In this way, Goodwin has some creative control over the project; the source material influences the machine’s vocabulary and sentence structuring, and hence the tone of the piece.

The Thoughts Beneath the Words

The problem with artificially intelligent novelists is the same problem with conversational artificial intelligence that computer scientists have been trying to solve from Turing’s day. The machines can understand and reproduce complex patterns increasingly better than humans can, but they have no understanding of what these patterns mean.

Goodwin’s neural network spits out sentences one letter at a time, on a tiny printer hooked up to the laptop. Statistical associations such as those tracked by neural nets can form words from letters, and sentences from words, but they know nothing of character or plot.

When talking to a chatbot, the code has no real understanding of what’s been said before, and there is no dataset large enough to train it through all of the billions of possible conversations.

Unless restricted to a predetermined set of options, it loses the thread of the conversation after a reply or two. In a similar way, the creative neural nets have no real grasp of what they’re writing, and no way to produce anything with any overarching coherence or narrative.

Goodwin’s experiment is an attempt to add some coherent backbone to the AI “novel” by repeatedly grounding it with stimuli from the cameras or microphones—the thematic links and narrative provided by the American landscape the neural network drives through.

Goodwin feels that this approach (the car itself moving through the landscape, as if a character) borrows some continuity and coherence from the journey itself. “Coherent prose is the holy grail of natural-language generation—feeling that I had somehow solved a small part of the problem was exhilarating. And I do think it makes a point about language in time that’s unexpected and interesting.”

AI Is Still No Kerouac

A coherent tone and semantic “style” might be enough to produce some vaguely-convincing teenage poetry, as Google did, and experimental fiction that uses neural networks can have intriguing results. But wading through the surreal AI prose of this era, searching for some meaning or motif beyond novelty value, can be a frustrating experience.

Maybe machines can learn the complexities of the human heart and brain, or how to write evocative or entertaining prose. But they’re a long way off, and somehow “more layers!” or a bigger corpus of data doesn’t feel like enough to bridge that gulf.

Real attempts by machines to write fiction have so far been broadly incoherent, but with flashes of poetry—dreamlike, hallucinatory ramblings.

Neural networks might not be capable of writing intricately-plotted works with charm and wit, like Dickens or Dostoevsky, but there’s still an eeriness to trying to decipher the surreal, Finnegans’ Wake mish-mash.

You might see, in the odd line, the flickering ghost of something like consciousness, a deeper understanding. Or you might just see fragments of meaning thrown into a neural network blender, full of hype and fury, obeying rules in an occasionally striking way, but ultimately signifying nothing. In that sense, at least, the RNN’s grappling with metaphor feels like a metaphor for the hype surrounding the latest AI summer as a whole.

Or, as the human author of On The Road put it: “You guys are going somewhere or just going?” - Thomas Hornigold

singularityhub.com/

In 2007, cars with cameras and tripods hitched on their roofs began roaming the streets of several American cities. Each tripod supported as many as fifteen cameras that captured footage of pedestrians, businesses, and street signs, stitching these images together into an immersive, panoramic image. This was the first fleet of Google Street View cars. They have since expanded throughout the world and to other means of transportation—from tricycles to snowmobiles. Ten years later, a Cadillac was outfitted similarly to a Google Street View car, but with the addition of an A.I. writing machine that converted images into words. It drove from Brooklyn, New York, to New Orleans, Louisiana, and produced 1 the Road (Jean Boîte Éditions), “the first novel written by a machine.” This gives new meaning to the concept of the road novel.

In many ways, the road novel could be considered the fullest expression of American freedom—cutting loose from the responsibilities and humdrum of daily life and escaping out into the vastness of America, so full of the unexpected. For much of the genre’s history, it has been a man in the driver’s seat. But as of late, its been imbued with fresh perspectives that are challenging the genre’s form and values, including The Golden State by Lydia Kiesling, which features a mother who has a “checklist” before she can take flight, and now, 1 the Road.

1 the Road, which won the IDFA DocLab Award for Storytelling, was created, not authored, by Ross Goodwin, a “gonzo data scientist” and former ghostwriter for Barack Obama, who, with the help of Google, rigged the Cadillac with a GPS unit, microphone, clock, and roof-top camera that fed information to the portable A.I. writing machine. As Goodwin drove from New York to New Orleans, the A.I. wrote “captions” to these images that were then printed on rolls of receipt paper 127-feet long, undoubtedly an homage to Jack Kerouac’s legendary first draft of On the Road, which he typed out on a single scroll 120-feet long.

The car itself is the pen. But, then, who is the author? Goodwin calls himself a “writer of writers” and “not a poet.” Others might call him a programmer or “creative technologist.” Though Goodwin has surrendered creative license to the writing machine, he nevertheless created the machine and the rules by which it operates. Not insignificantly, he selected the sources of input, including “nearly 200 hand-picked books” that, in composite, form the linguistic matrix that informs the A.I.’s literary sensibilities, from word choice to sentence structure.

This novel, which unfolds over the course of three days, reads more like a long poem than a narrative with a conventional arc. It begins, “It was nine seventeen in the morning, and the house was heavy,” a surprisingly apt beginning to a road novel, for a machine. Alongside the writing is a column of timestamps that log when each entry was written, as if it were an observational journal a scientist might keep when conducting an experiment. The entries are brief, no more than a few sentences long, and, unless it cites the same place, are rarely connected to the previous entry. The first day concludes with a brilliant coda, “It was seven minutes after ten o’clock in the evening. The station was deserted. The path was already in the sun.”

As evidenced by these two excerpts, the A.I. relies on certain formulas when constructing a sentence, one of which is citing the time. In the beginning, it relies on this construction with Homeric frequency to the point that this road novel seems more like a journey through time than space. In addition to the column of timestamps, the book’s sections are organized around the time of day rather than place or destination. However, as the novel progresses, other sentence structures do appear (thankfully), as if the A.I. is learning (uncannily).

Though the A.I. is programmed for English, it speaks a foreign dialect. “It’s not quite human level,” says Goodwin, “more like an insect brain that’s learned to write.” The odd poetic idiom produces unexpected turns of phrase that are sometimes funny, sometimes profound, and often nonsensical. There is an inescapable, and perhaps unhelpful, urge to find a pattern in its loose grasp of grammar and lottery word choice.

Because of this linguistic tic, sentences that read more or less as normal, like the opener, are applauded, as one would do with a toddler. At other times, these sensible words carry a degree of gravitas: “It was nine twenty-five in the morning. He lifted his head and said, You know, I was not looking for you, you know. Its a mistake. I wouldnt [sic] want to be with you.” The clarity of the statement cuts through the jungle of words and commands special attention. It is like listening to an elder suffering from Alzheimer’s who, for a brief moment, is lucid and strains to voice a last request.

The experience of reading 1 the Road is not unlike being on a road trip. If the car is the pen, then, in a funny way, reading 1 the Road is almost like riding shotgun. Once the reader gets a handle of the writing patterns and the poetic idiom, it is easy to go on cruise control. By that I mean it is not necessary, nor enjoyable, to read this novel closely. It is best skimmed, page after page, like stripes on a highway. Luckily, there is a steady stream of poetic breadcrumbs to keep the reader nourished and motivated. 1 the Road is equal parts profound (“Car on the road had been looking into each others [sic] faces, which had to be descended to the police station behind them”), poetic (“A patch of water was still looking for some organization, and his lips were falling in vain, a distant silence. The water is dark and seems to be a container, and the stars are still breaking out”), and always unexpected (open to any page).

The time is thirteen minutes after five in the evening, and I write this from a train, wondering, what would this train write as it catapults down the Hudson River and shores up in the dark tunnels of Grand Central? I do not know, but I would like to find out. - Connor Goodwin

https://bombmagazine.org/

On March 25, 2017, a black Cadillac with a white-domed surveillance camera attached to its trunk departed Brooklyn for New Orleans. An old GPS unit was fastened atop the roof. Inside, a microphone dangled from the ceiling. Wires from all three devices fed into Ross Goodwin’s Razer Blade laptop, itself hooked up to a humble receipt printer. This, Goodwin hoped, was the apparatus that was going to produce the next American road-trip novel.

The aim was to use the road as a conduit for narrative experimentation, in the tradition of Kerouac, Wolfe, and Kesey, but with the vehicle itself as the artist. He chose the New York-to-NOLA route as a nod to the famous leg of Jack Kerouac’s expedition in On the Road. Underneath the base of the Axis M3007 camera, Goodwin scrawled “Further.”

On the day they were set to embark, Goodwin and his travel companions—his sister Beth, his fiancée Lily Beale-Wirsing, his friend Nora Hamada, Kenric McDowell and Christiana Caro of Google, and a small film crew led by Lewis Rapkin, who would follow along in a van to document the journey—gathered near Ross’s Bushwick apartment to rig the system onto the Cadillac. (Google, which had become interested in his work at NYU, footed the bill for the car rental and the camera—a year later, the search giant would hire him to work on its Artists and Machine Intelligence program.)

“The reason it’s a Cadillac, by the way,” Goodwin tells me in a phone interview, “is we wanted it to be done in an authoritarian vehicle, and we couldn’t get a Crown Vic.” He worried that if passersby saw a car loaded with home-brew electronics, wrapped in wires, they might mistake it for a terrorist vehicle; instead, he wanted to nod to the tacit acceptance that federal agencies routinely carry out such surveillance. “I wanted people to see it as something associated with government officials.” Mission accomplished, apparently: Goodwin says he learned later that as they were preparing to leave, a nearby bodega owner saw the car and the surveillance equipment and decided to keep his shop closed for the day. “It’s not an ad for Cadillac,” he laughs. “In fact, they turned us down.”

The machine received its first jolt of inspiration just as soon as Goodwin and his traveling companions fired it up in Brooklyn. It wrote: “It was nine seventeen in the morning, and the house was heavy.” For an opening sentence in a book about the road, it’s apropos, even poignant.

The AI translated the sights and sounds of aging East Coast infrastructure, a right-wing protest that halted traffic for a while, the passing flora and fauna, and, presumably, the stop at a convenience store where Goodwin tells me he had to pick up an extra power adapter for the cigarette lighter because his system wasn’t getting enough power.

Goodwin clearly views the four-day journey as a success, even a surprising one. “I thought there was a possibility that there would be an arc, that it would feel like a novel,” he tells me, “and that’s what happened. Aspects of it feel like a novel.” He says the fact that the car itself serves as a character gives it a sense of continuity that much AI-generated fiction lacks.

“I’ve read the whole thing, in case anyone’s curious,” Goodwin says, laughing. “Coherent prose is the holy grail of natural-language generation—feeling that I had somehow solved a small part of the problem was exhilarating. And I do think it makes a point about language in time that’s unexpected and interesting.” So do I, actually. I sat down to read the whole thing in one sitting, as Goodwin suggested I do, and more or less succeeded. I’m not sure there’s a cohesive arc in any classic narrative sense—but there is plenty of pixelated poetry in its ragtag assemblage of modern American imagery. And there are some striking and memorable lines—“the picnic showed a past that already had hair from the side of the track,” struck me, for one.

It’s a tour of the built and noisy world, as interpreted by those machines. It’s surveillance-technology fiction, written by the same species of technology that is conducting the surveillance and processing the data. What might an AI author teach us about a world already so totally sculpted and impacted by the kind of data it’s gathering that a human writer can’t?

Goodwin seems committed to finding out. “This is very much an imperfect document, a rapid prototyping project. The output isn’t perfect. I don’t think it’s a human novel, or anywhere near it,” Goodwin says, but “there are characters in it, which is really strange.” A mysterious painter, for instance, appears in the third line to ask, “What is it?” It continues to show up throughout: “A body of water came down from the side of the street. The painter laughed and then said, I like that and I don’t want to see it.” Insofar as it’s tempting to locate the writer (or writer of the writer) in the work—as we inevitably do in road-trip fiction—the painter seems the most logical stand-in for Goodwin himself. “I could have made a big start off,” the machine-generated painter says at one point, making it easy imagine it’s talking about the project itself, nodding to new frontiers. “I want to go away from here, the time has come.” -

Ross Goodwin: Adventures in Narrated Reality: New forms & interfaces for written language, enabled by machine intelligence

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.