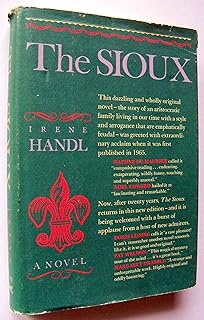

Irene Handl, The Sioux, Knopf, 1965.

French, feudal, fabulously rich and fiercely tribal, the Benoirs call themselves The Sioux. The latest addition to the tribe is Vincent Castleton, a genial, short-tempered Englishman, and now third husband to the elegant, autocratic Marguerite, still in her twenties and very much née Benoir. The impending arrival of Marguerite's son George is making Castleton very nervous.

When the boy does arrive, his trappings - servants, two Rolls Royces, a bodyguard - seem to confirm Castleton's worst fears. Yet far from being the spoilt brat he expected, George turns out to be an intoxicating, delightful child who quickly wins Castleton over and who must be protected from his mother. She is beginning to prove more than Castleton bargained for...

Qu'est-ce-que c'est que ca? It's a high camp, low comedy routine-- the first novel of a sixty year old actress who is known as the ""Queen of Chars."" Peter Sellers says ""What a wild book this is... it's a Cook's tour..."" He means kooks. It commutes between Paris and Auteuil and the Deep Delta and it is bi-lingual, British with a touch of Cockney, French with a soupcon of Creole. More precisely, it's a book length betise or nonsense about a rich, inbred and intensely voluble family, the Benoirs, who think of themselves as a tribe and call themselves the Sioux. Marguerite Benoir, whose first husband had been her first cousin and who is still surrounded by all kinds of in-laws and ex-laws, has recently married her third husband, Vincent Castleton. He now becomes the Petit-Papa of her invalid nine year old son, Georges-Marie, whose alternate soubriquets are Puss and Moumou. Along with thirty million, Moumou has inherited megaloblastic anemia. Castleton, a good sort actually, takes to the little sod who is either being cosseted or whipped by his mother. She seems just as likely to do him in as his megaloblastic anemia. Now, they're a talkative lot, these Benoirs, and sometimes there's a little action-- what they call sleeping au grand lit-- and sometimes one is likely to ""die of ennui."" But you can learn a little non-Berlitz French since every line is garni with petits pet words like cheri and chouchou along with some occasional Anglo-Saxon improprieties... Well? Hein It's outre-geous. - Kirkus

A reprint of the 1965 fiction debut by a then-60-ish British actress. From the 1965 Kirkus review: ""A high camp, low comedy routine. . . about a rich, inbred and intensely voluble family, the Benoirs, who think of themselves as a tribe and call themselves the Sioux. Marguerite Benoir, whose first husband had been her first cousin and who still is surrounded by all kinds of in-laws and ex-laws, has recently married her third husband, Vincent Castleton. He now becomes the Petit-Papa of her invalid nine-year-old son, Georges-Marie, whose alternate sobriquets are ""Puss"" and ""Moumou"". . . Now, they're a talkative lot, these Benoirs, and sometimes. . . one is likely to 'die of ennui.' But you can learn a little non-Berlitz French since every line is garni with petits pet words like cheri and chouchou along with some occasional Anglo-Saxon improprieties. . ."" A modestly welcome retrieval for connoisseurs of camp--but don't be taken in by the republication hype. - Kirkus

Daphne du Maurier found it "compulsive", Margaret Drabble thought it "oddly haunting", Nol Coward saw genius in it and Doris Lessing said she couldn't remember another novel remotely like it - "it is so good and original".

The Sioux appeared in 1965, followed in 1972 by its sequel, The Gold Tip Pfitzer. Their author was no enfant terrible nurtured on creative writing courses but a 62-year-old character actress - Irene Handl. What surprised critics was the gap between the stereotyped roles in which Handl specialised (loveable cockney landladies, eccentric mediums) and her savagely individual fiction.

Castleton's wife Marguerite, beauty and queen bitch, is 26 and already on her third marriage. In her bureau she keeps a whip once used on household slaves. It comes in useful when she wants to beat her nine-year-old invalid son George into submission. ("I don't spoil him... I love him far too much to let him make a nuisance of himself.")

If it sounds camp, that's because it is. Characters natter in Ol' Kintuck ("P'tit m'sieu gettin' to look more like Madame votre mre ever' day"), and even old Castleton addresses his brother - a colonel - as "old darling" and "old dear".

Reading The Sioux and The Gold Tip Pfitzer is like eating one marron glac too many: something between sweetness and nausea. Even nature is shown as cloying and rotten - "the rocking wands of hundreds of buddleias... candied with a coating of flies". Handl's material is melodramatic, but there's more to it than Lace. When George dies, welded to his elegant mother - his adored oppressor - by blood and mucus, the scene is genuinely moving.

Handl's style is instinctive and fresh rather than tutored. ("I never stayed at any school more than half an hour. I never learnt a thing.") Both books consist almost entirely of dialogue and interior monologue, and Handl delineates character through rhythm. ("Woozy looks fabulous tonight, Bienville decides. Just as he likes him, spooky as hell and deliciously ready for the mortician.")

Meeting Handl before she died, I heard how her novels were written "in a great sort of wave". Castleton was based partly on Handl's Austrian banker father. (Her mother was French.) Marguerite was a former employer, "a hateful woman, hateful". Handl even designed the book cover herself. "I had nothing to draw it with except Max Factor make-up, Biro and rouge."

Handl intended to write a third book, but time ran out. As a person of "violent dislikes", Handl confessed, "I dislike people that think a terrible lot of money. Except they're very funny, and I write about them nastily." Nastily and extremely well. - Marianne Brace

Little did I suspect when I stumbled

upon The Sioux in the fiction section of a second-hand bookshop that

lurking beneath its deceptive title I’d find a neglected

masterpiece of high camp Southern Gothic - one written by, no less, a

British character actress famous for being typecast as a humble

charwoman. Irene Handl’s 1965 work is almost undoubtedly the sort

of book one should simply read and let be read. But I’m unable to

contain my… my what? Enthusiasm? Bewilderment? Awe? Horror?

Bouche-bée-edness? Handl’s ferocious, sui generis novel quite

nearly gave me the screaming habdabs.

The Sioux has next to nothing to do

with Native Americans. The title refers to the name the Benoirs apply

to their own outré tribe: an aristocratic French family exiled to

the Antilles and then to Louisiana around the time of the Revolution,

and whose current generations shuttle between opulent homes in and

around Paris and New Orleans. The novel opens with a phone call

between Marguerite Benoir (a.k.a. Mimi, a.k.a Mims, a.k.a. the

Governor of Alcatraz) and her beloved eldest brother, the family head

Armand (a.k.a. Benoir, a.k.a. Herman), who, at his house outside

Paris, has been tending to Marguerite’s son George-Marie while

Marguerite and her new husband, British banker Vincent Castleton,

honeymoon their way around the world. The conversation centers on

young George-Marie, whom Armand plans to accompany on the next boat

to New Orleans to reunite him with his mother and new papa-chéri.

Other characters rounding out the “general bashi bazoukerie” of

this filthy rich troupe include Armand’s mousey wife Marie, his

spoiled young adult son Bienville (a.k.a. Viv), whose marriage of

convenience to an Elaine in France is impending, and a whole host of

servants, most of whom appear to be descended from the slaves owned

by Benoir ancestors before the Late Unpleasantness. Oh, and there’s

a monkey, Ouistiti, who hangs about on Armand’s shoulder, stealing

food and baring his teeth at just about everyone.

The Sioux themselves are scarcely more

civilized. They carp and snipe at one another, throw their weight and

privilege around to get what they want, castigate the servants, use

the word “chic” a lot, display bursts of violence and an evident

regret over the demise of slavery, and live “in a perpetual state

of je m’en-foutism… under the impression that they are still

living in pre-secession and are happy to spend the rest of their

lives up to the eyebrows in spanish moss.” Few books I’ve read

contain so much sheer nastiness; there’s almost no difference this

family hasn’t explored in its own way, from incest to a capacity

for outrageous venality to a disdain for those “Apaches” outside

the tribe (including the newest interloper, Castleton). At 26, the

beautiful and cruel Marguerite has already been married twice before,

first to Georges, a French race-car driver killed in an auto accident

outside of Chantilly while swerving to avoid an animal, then a

short-lived second marriage to the rich, reactionary Governor Davis

Davis of Mississippi. Castleton is both amused and scandalized by the

monstrous family into which he has been wed. Sensing that he’ll

always remain an outsider, his attitude echoes a claim of

George-Marie: “Oh, it is farouche the way Benoirs will look at you,

as if there is not a single part of you they do not own.”

The novelty of this cast of miscreants

might on its own lift The Sioux well beyond mere camp, but further

elevating its literary pedigree is Handl’s dangerously inventive,

rapid-fire language, mesmerizing to the point of éblouissance. Handl

is able to switch moods on a franc; there are some extraordinarily

poetic passages, which almost instantly give way to the whole

vaudeville show. Rafts of prose appear in Franglish, reflecting the

Benoirs’ blend of formal French and Queen’s English with elements

of Louisiana Creole, “Ol’ Kintuck” and “Miss’ippa” thrown

in. That’s not even counting George-Marie’s peculiar grammatical

convolutions, Castleton’s Anglicisms, his manservant Bone’s

idiomatic Cockney and a constant eruption of Siouxian neologisms,

such as “creolising” to refer to the servants’ tendency to

lapse into languor when the Benoirs aren’t around.

An out of context quotation may be as

likely to send potential readers scurrying for cover as to draw them

in, but I’ll provide one here to give a flavor, with the caveat

that one glittering excerpt scarcely hints at the novel’s

considerable depths. The scene is the end of a Benoir dinner, as

young George-Marie heads off to bed:

He is replete with Iced Melon,

Homard Thermidor, Happiness, Kisses, Cailles en chemise, Champagne,

Love, Filial Piety, Champagne, Colibris and Humming-birds, More

Champagne, a Little Brother, Ouistiti, Salade à l’Orange, Pommes

duchesse, Viv’s wedding, Asperges, Sauce Mousseline, Shyness,

Father Kelly, Putting Oneself Last, Fraises à la crême, two tiny

Petits Fours shaped like paniers des roses, More Champagne, a taste

of maman’s Crépes Suzette, Obedience, Nice Fruits from everybody,

and an oyster direct from the Brochette d’huîtres served as a

special attention to Mr. Castleton who is the favorite of them all

and don’t eat desserts much.

The Sioux also employ a panoply of

nicknames for one another so dizzying that I had to read the first

chapter a second time just to get a handle on who was who.

George-Marie, for example, possesses “more names than Jehovah,”

including George-Marie, George, Marie, Puss, Moumou, the Wizard,

Ducky, the Dauphin, King Nutty, les Spooks and Thingo, to name but a

few.

The gravitational center of The Sioux

resides in this minable nine-year-old, one of the most singular,

memorable literary characters I’ve encountered in a lifetime of

reading. This moony mixture of vulnerability, innocence, fragility,

precocity and defiance is a lost child caught up in the competing,

selfish interests of his various family members, their swirl of

languages and international hop-scotching, their parental and

familial inadequacies. Fed on oysters and champagne and suckled with

“canards” (sugar cubes in spoons of cognac and coffee),

George-Marie suffers from social isolation and the fact not only of

resembling his deceased Delta-born grand-mèmère, revered and

detested in equal measure by other family members, but also of having

had already, in his short life, three different fathers spread across

two continents and an insufferably immature mother whose behavior

towards her son ranges between smothering attention and appalling

verbal and physical abuse. The hapless George - pale, bruised,

skeletal, “whose natural habitat is the firing line, and whose

nerves in consequence are one delicious quaking jelly“ - is given

to bouts of spontaneous crying. Castleton quips that the boy has no

tear ducts, but rather “a Device, like windscreen wipers” which

should be loaned out to wash down the cars. Most significantly, in

this rarified world of privilege floating high above the grim

realities of life, George represents one inescapable, grim reality

that pierces privilege’s bubble: he is severely ill, stricken with

megaloblastic leukemia.

***How did such a thing come into being? I’m at a loss. No obvious literary precedents come to mind, and the idea is so original that it must have emerged from deeply idiosyncratic personal experience. Handl’s own mother was French, but my suggesting any personal history at play here would be purely conjectural. Handl’s indelible characters seem simultaneously like grossly-inflated caricatures and completely flesh and blood, and the manner in which she can maneuver almost seamlessly from melodramatic absurdity to the most tender and abject realities astounds. Those abject realities include the South’s original sin, its legacy of slavery, here reproduced and perpetuated in a grotesque dynamic of arrogance, privilege and punition. I even wondered if the novel might have originated from Handl’s having come into actual contact with the object that in The Sioux takes the place of Chekhov’s gun-in-the-first-act, a beaded whip, a “soupir d’amour,” small enough to fit in a coat pocket and handed down from a previous generation of slave-owning Benoirs, a repugnant object which, like a coiled serpent in the garden, alters the story in an irrevocable way.

Handl balances her tale at the acute

angle where the pathos of this terminally-ill child meets the

limitless sense of entitlement and invincibility of his ingrown

family, a tension Handl exploits to relentless comedic effect, yet

without the affectation of zaniness for the sake of zaniness. An

undercurrent of indignation runs beneath the most comical scenes.

“Mon dieu, hold him properly, Vincent! He won’t break! He isn’t

made of sugar, you know!” exclaims Marguerite while chastising her

husband for allowing George-Marie to kiss him on his probably

germ-filled mouth. If there’s any moral compass in the novel, it’s

Castleton, who soberly reflects in response, “That’s all she

knows about it. He is made of purest meringue. The slightest pressure

and all they would have left is a pretty little hill of sparkling

white sugar.” Handl combines her campy comedy with a fierce moral

sense, making The Sioux at once laugh-out-loud funny, unabatedly

cringeworthy and caustically, emotionally devastating.

Irene Handl published just one other

work of fiction, a 1977 sequel to The Sioux entitled The Gold Tip

Pfitzer. The sequel, taking up where the first novel left off and

moving the action to Paris, is certainly worth reading. However, it

feels almost superfluous, like an additional bonbon when one is

already full but can’t (and won’t) say no to more. It primarily

serves to provide the reader an extended opportunity to spend a bit

more time in the world of the “ruddy, habit-forming Sioux,” this

complex, awful, intoxicating family to whom even Castleton, in

perhaps the best position to recognize the tribe’s abysmal

failings, admits “an addiction.”

Bien entendu. - http://seraillon.blogspot.com/

Irene Handl, The Gold Tip Pfitzer: A Novel, Allen Lane, 1972.

The Gold Tip Pfitzer of the title is a variety of cypress much favoured in cemeteries, a depressing evergreen with scrambled-egg-yellow-tipped branches, supposed to typify hope amidst the encircling gloom. The death in this case is the death from leukaemia. A novel by much-loved actress Irene Handl about two families, one French, one English and the death of a child.

This brief postscript to Handl's first novel, The Sioux, shares the elegance and ferocity of its predecessor but leaves a much nastier aftertaste. The self-indulgent, self-absorbed antics of the Benoir familythe Sioux, as they like to call themselvesare less amusing and more horrifying than they were before, mostly because they take place around the deathbed of Marguerite Benoir's nine-year-old son. The boy's death also signals the end of Marguerite's marriage to Englishman Vincent Castleton; by the end of the book, we fully share his disgust and rage at the Sioux lifestyle. One admires the author's courage in making her characters so utterly true to their despicable code of behavior, and they certainly have a distinctive vitality and insouciance, yet after a few chapters their glamorous decadence palls. Handl is an excellent stylist, and The Gold Tip Pfitzer is compulsively readable, but it's too unpleasant to be much fun. - Publishers Weekly

In this sequel to the author's 1965 The Sioux (cf. p. 64), those inbred French grandees, whose ""fierce tribalism causes their fierce hearts to beat as one,"" entwine their attenuated sensibilities (expressed in an often-wanton English splattered with dollops of French) about the approaching death of an heir before the mini-Gotterdammerung close. Two from the same pride-pod, Armand Benoir and thrice-married sister Marguerite (""Mim""), rally subordinate Benoirs to attend the dying days of nine-year-old George, a precocious and engaging squirt who is terminally ill with leukemia, a genetic family curse. George revives and withers in Paris and at the Benoirs' country preserve. Among those in attendance: Mother Mim, for whom the dauphin is ""the absolute center of her universe"" and who lies in bed with brother Armand (""We try to get a little sleep together. Is that so bad?""); Vincent Castleton, Mim's third husband, who bores her to blankness and whose very English outrage at the Benoirs for not pushing crisis treatments for George glances off the silken certainties of the family, which has a special way of cherishing its own; Bienville, Armand's sole offspring who loves/hates Papa, and has even wed an English ninny who's decorating a big, beautiful Drekpalast (all ""vulgaire, commun, ordinaire, de mauvais gout et banal"") to infuriate Papa and his ""high-class shines."" Then there's Armand--that ""sexual excÉdÉ"" Castleton rather likes--with his pure doll-wife, his lascivious pet monkey, a mistress, and a private leukemia clinic called ""the Ritz."" The Benoirs soldier on, but Death--leaving only the chief Sioux standing--out-bizarres them all (George vomits ""raspberry ice""; he dies while a mob of family and medicos skate on a rink of mucus and blood, ""charging about like Keystone cops trying to force an arrest""). And Bienville's suicide is a Performance--sexually speaking. This novel, dealing as it does with death--both as viewed through a dilettante monocle, and as a heart-stopping invasion--has more spine than the campy The Sioux; and the surface glitter of the speech ranges from un peu tiresomely arch, to burlesque, to blackly funny (Bienville sounds like Doonesbury's Zonker). Still, in spite of the fancy-pants palaver, there are electric moments worth catching. - Kirkus

In 1986 I spent the whole of June in a rented house in Brittany. There were three of us, myself with a book to finish, and two painters. One was painting still lives (taking up most of the kitchen table) plus the occasional church interior, the other was finishing work for a looming exhibition in London. We were far from the sea, inland near St Theggonec. We all worked hard without distraction until the evenings. There was no television in the house, and no cinema for many miles, so we were reduced to….yes…. reading aloud…I had brought several books with me, among them Black Mischief by Evelyn Waugh which I could barely read out for laughing so much, and a curiosity (I thought) called The Sioux, written by Irene Handl. I had bought the paperback partly for its once modish 1970’s cover by Peter Bentley and partly out of a sense of puzzled disbelief, what would a novel by the wonderful character actress and comedienne Irene Handl possibly be like? The answer was, in a word- astonishing.

I read the whole book out loud on succsessive evenings and all three of us were amazed and delighted by it. She had a real gift, she was a real writer no doubt. Her story of the camp aristocratic and over civilised French family in New Orleans is as original and remarkable as its author. Written in a kind of short hand private language which eventually reveals its meanings through oblique humor in a very orginal way. Try and seek it out and its sequel The Gold Tip Pfitzer, there are bound to be copies on Abe books.

The Sioux by Irene Handl published by Longmans 1965

The Gold Top Pfitzer by Irene Handl published by Allen Lane 1973

I have added a short clip of Miss Handl in, Morgan A Suitable Case For Treatment, a glimpse of one of her finest and most characteristic performances…. - Ian Beck

https://ianbeckblog.wordpress.com/2011/05/07/irene-handl-as-novelist/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.