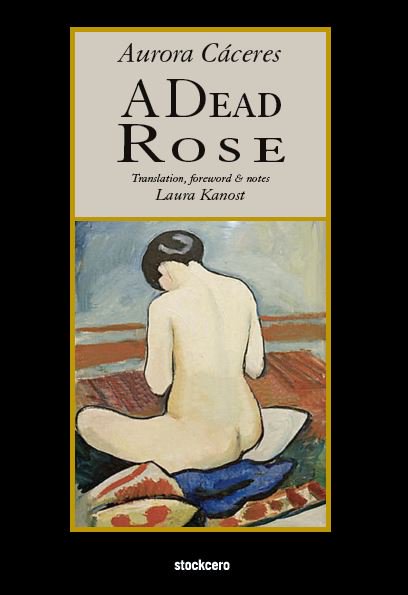

Aurora Cáceres, A Dead Rose, Trans. by Laura Kanost, Stockcero, 2018. [1914.]

Unfairly forgotten Peruvian feminist writer Aurora Cáceres(1877-1958) has gained a new wave of readers in the 21stcentury -ironically, through her engagement of a literary movement, Spanish American modernismo, that denied women writers a place.

Published in Paris in 1914, Cáceres's novel La rosa muerta, translated by Laura Kanost as A Dead Rose, stands today as the most influential modernista prose work penned by a woman. In this audacious story of an ailing woman who initiates an affair with her gynecologist, Cáceres not only defies cultural conventions of feminine modesty to speak publicly about women's health and sexuality, but does so by appropriating the language of a literary movement that silenced women.Unlike her most of her contemporaries, Cáceres does not reduce illness to a clinical case, an example of degeneration, or a symbol of social ills -nor does her protagonist's affliction merely signal the social deviance of the modernistaintellectual or the beauty ascribed to the objectified modernistawoman, seen as still more beautiful if languishing or dead.

Rather, Cáceres portrays illness as a multifaceted experience that is affected by the social context within which it takes place and ultimately is not overcome through modern medicine. Left to carry on into the future are two characters who thrive because they are not constrained by gender conventions: a nurturing, selfless male doctor devoted to science, and his beautiful and deeply intelligent young daughter.

A Dead Roseis an extension of Cáceres's cosmopolitan identity and feminist stance developed over a lifetime of travel and scholarship. The daughter of a Peruvian president, Cáceres was equally at home in the Americas and Europe. She founded numerous feminist and cultural organizations and authored essays, novels, short stories, and life-writing, including a memoir of her turbulent marriage to famed Guatemalan modernistaEnrique Gómez Carrillo.

Steeped in the modern technologies, fashions, and social networks of early 20th-century Paris and Berlin, this brief and engaging novel will appeal to readers interested in gender and women's studies, global literature, and medical humanities. Dr. Kanost's introductory study contextualizes the novel within the author's production and explores its connections to modernismoand feminism, engaging the critical conversation that developed in the wake of the novel's second edition, prepared by Dr. Thomas Ward (2007).

The female form is often idealised in art and media, from classical sculptures through paintings and in more modern times with fashion photography and the general objectification of women. It takes a brave woman to take on those stereotypes and play with them, which is what Peruvian author Aurora Cáceres does in this fascinating novella.

Cáceres was an intriguing and mercurial woman; the daughter of a Peruvian president, she travelled widely in the Americas and Europe, writing novels, essays, short stories and memoirs, as well as founding a number of feminist and cultural organisations. Married briefly to a famous Guatemalan author, Enrique Gómez Carrillo, she mixed with many artists working in the modernista movement (in which she and Carrillo could be included). Blending Romanticism and Symbolism (amongst other things) modernista work was highly stylised, dealing with inner passions, visions, harmonies and rhythms and going on to have great influence in the Hispanic world. However, Cáceres was a rarity in the movement, and according to the useful notes and introduction that support the book, this was a literary culture which silenced women.

A Dead Rose, originally published in 1914, tells in elliptical, often lush prose the story of Laura, a rich young widow, and the course of her illness. In remarkably frank fashion for its time, the book relates her visits to her gynaecologist, her response to her ailment, her decisions as to how to deal with it, and her eventual fate. After visiting a number of doctors, and suffering the humiliations of physical examination by strangers, she finally is treated by Dr. Castel; with whom she initiates a passionate affair. Both parties are caught up in a whirlwind of emotion, but both have different ideas about how the disease should be dealt with.

However, there is much more going on in this book apart from the surface-level narrative of disease and passions. Cáceres is actually taking on a movement that prized female beauty above all; and Laura regards her physical appeal as vitally important, and indeed is idealized by her lover. However, there is also a strong emotional link between the two and the book seems to suggest that a total communion between two people depends on both the physical and the emotional. Science and medicine are venerated but in the end rejected; Laura eventually symbolically destroys the idealised female body by choosing to reject surgery, leaving herself externally untouched whilst internally decaying. That disjuncture is returned to again and again, as if Cáceres is reminding us that the surface level of image is false and the real person is what lies under.

Cáceres was also breaking taboos by dealing with the subject that she does, namely a gynaecological disorder. Laura is suffering from fibroids, a complaint that nowadays would be treated promptly and usually would cause minimal issues; however, at the turn of the 20th century, with more primitive medical procedures, the option for Laura is surgery which would destroy the image she has of herself. Laura prefers love and ignorance and death against an operation, what she sees as physical defilement and the consequent loss of love, enjoining her lover to remember her as perfect. Time and again in the narrative both Laura and Dr. Castel brood and muse on her figure and what it represents, as she almost becomes an allegory for heavenly beauty. Passion and perfection are more important than real, human life and love.

For a short work, A Dead Rose takes on some remarkably complex ideas, and its frankness of subject matter is quite ground-breaking. Some of the trysts between Laura and the doctor take place in his consulting room, which must have shocked readers of the time; and in addressing the embarrassment that a modest woman must have felt in the simple act of undressing in front of a strange man, Cáceres reminds us of the restrictions surrounding women and how difficult it must have been to actually deal emotionally with seeking treatment for this kind of issue. The surgeries of the doctors who Laura initially visits are bleak and dirty, to be contrasted against the pristine rooms of Dr. Castel and again there is the juxtaposition of beauty and decay.

As a story in itself, A Dead Rose works well, relating the emotional entanglement, the physical issues and the final fate of Laura. However, the subtext to the story is obviously crucial and I did wonder a little if Cáceres had managed to get her point across; if she was trying to say that the idealization of women is damaging and that the physical form is actually less important that what is under the surface, I’m not sure she entirely succeeded. Laura still suffers the ultimate fate to retain her beauty, but I would have liked to see perhaps Cáceres give her heroine an alternative future where she was not so defined by her looks but instead allowed to rely on her mind and the intelligence she so obviously displays in her relationship with Dr. Castel.

This is a minor criticism, however, because A Dead Rose is such a pioneering novel. Multi-layered, evocative, frank and revealing, it most definitely deserves to be rediscovered. This Stockcero edition is translated by Dr. Laura Kanost, who also provides notes and a scholarly introduction, which gives marvellous background and context for the novel, and goes into much more depth than I can here. A Dead Rose is a ground-breaking feminist work; in allowing her heroine to embrace and control her own sexuality and physical needs, Cáceres was most definitely ahead of her time! - Karen Langley

https://shinynewbooks.co.uk/a-dead-rose-by-aurora-caceres/

When I was a grad student, I passed up the opportunity to take a course on Spanish American modernismo with a brilliant professor because I couldn’t stand the thought of a whole semester reading modernista writing. What bothered me most about modernismo was the way it objectified and excluded women. So when I was planning my own early 20th-century Spanish American narrative course at K-State, I wanted to juxtapose a well-known modernista text with one authored by a woman. With my students, I read and thought about what it meant for Peruvian Aurora Cáceres to write her 1914 novel La rosa muerta as a modernista text. Her protagonist is obsessed with making her own body a perfectly beautiful object—very modernista—but her body is not perfect at all: she has a life-threatening uterine ailment. How many novels, from any culture or time period, can you think of that narrate a pelvic exam? Cáceres defies cultural norms by discussing her female protagonist’s gynecological illness and treatment (including scathing criticisms of medical practices), and by depicting a sexual relationship between the protagonist and the devoted, progressive doctor she eventually finds.

In the introduction I wrote for my translation, A Dead Rose, I needed to explain for readers unfamiliar with modernismo why Cáceres wrote the way she did. During my sabbatical this semester, I read everything Cáceres had written leading up to this work, everything scholars have written about Cáceres, and many discussions of women and modernismo. One of the most exciting parts of this process was getting my own copy of the first edition and getting to read the second novel published in the same volume. Hardly anyone has access to this other novel, Las perlas de Rosa, so I wanted to include a detailed description of it in my introduction. In the early 20th century, part of the charm of reading a new book was cutting the pages apart as you read. The copy I bought had gone a century without ever being read, so I had to cut the pages to read them!

It was a fun challenge to find ways to make the novel’s elaborate modernista language work in English. I used Google Books, the Biblioteca Nacional de España Hemeroteca Digital, the Oxford English Dictionary, and the Nuevo Tesoro Lexicográfico de la Lengua Española extensively to research fashion and technology terms and to check historical usage in both Spanish and English. For example, in the early 20th century, promiscuo/promiscuous also meant “varied, heterogenous,” so when the narrator uses this word to describe the women in the doctor’s waiting room, I had to convey the right idea to today’s readers. We do a lot of terminology research in Advanced Translation, SPAN 771, and this year I will be adding an activity using historical dictionaries inspired by my research for this novel. - Laura Kanost

https://kstatespanish.wordpress.com/2018/04/30/a-dead-rose-in-english-translation-by-dr-kanost/

Zoila Aurora Cáceres Moreno (1877–1958) was a writer associated with the literary movement known as modernismo. This European-based daughter of a Peruvian president wrote novels, essays, travel literature and a biography of her husband, the Guatemalan novelist Enrique Gómez Carrillo.

Her life itself is intimately intertwined with Peruvian history, the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), the Peruvian Civil War of 1895, and an intellectual's exile in Paris. Her essays have recently begun to receive critical attention by scholars attempting to understand modernism from a gendered perspective. During the War of the Pacific, her sister was killed while her family was fleeing from the Chileans. Her father Andrés Avelino Cáceres, at that time a Colonel in the Peruvian Army, was mounting a guerrilla war against the occupying army. Peru (and Bolivia) lost that war and the Chileans occupied Lima, the country's capital. After the Chileans departed, now General Cáceres served in a variety of functions, as a diplomat in Europe, president of the Republic, and then exiled after a bloody coup in 1895. All of these events affected Zoila Aurora Cáceres, who was educated by nuns in Germany and at the Sorbone in Paris. She was known to many of the major modernista authors including Amado Nervo, Ruben Darío and Enrique Gómez Carrillo, whom she married.

Besides her interesting life, she left behind political tracks and a wide gamut of writing. Regarding the former, César Lévano points out the following: she founded Feminine Evolution in 1911, in 1919 she organized a feminine strike for food, while in 1924 she organized a new organization, "Peruvian Femenism". She was a die-hard suffragist associated with Angela Ramos. Later she would work with the anti-fascist organization "Feminine Action".

Regarding the latter, Aurora Cáceres has left behind a varied and diverse output. Her compelling novel La rosa muerta, recently published by Stockcero for the first time in almost a century, was set in Paris where it was published in 1914. In a work sharing formal characteristics with modernista prose, Cáceres challenged the ideological parameters of the movement. While her protagonist appropriated the modernista precept of a woman as an object of male veneration, she also took active control of her sexual life in a world where husbands still treated their wives as objects. The objects in this novel are not people but implements of communication and medicine reflective of the apogee of the industrial age. The action, which takes place between Berlin and Paris, is representative of the places that the modernistas held dear, but the feminization of the portrayal of male-female relations broadens the scope of the male-dominated modernista literary paradigm. The ideal men in this novel are not the husbands from whom women run, but medical doctors, men of science who are liberated from chauvinist attitudes. The central character of “La rosa muerta” accordingly falls for one of her gynecologists, allowing for scenes in the Paris clinic that must have been scandalous for the 1914 reading public. - https://www.revolvy.com/page/Aurora-C%C3%A1ceres

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.