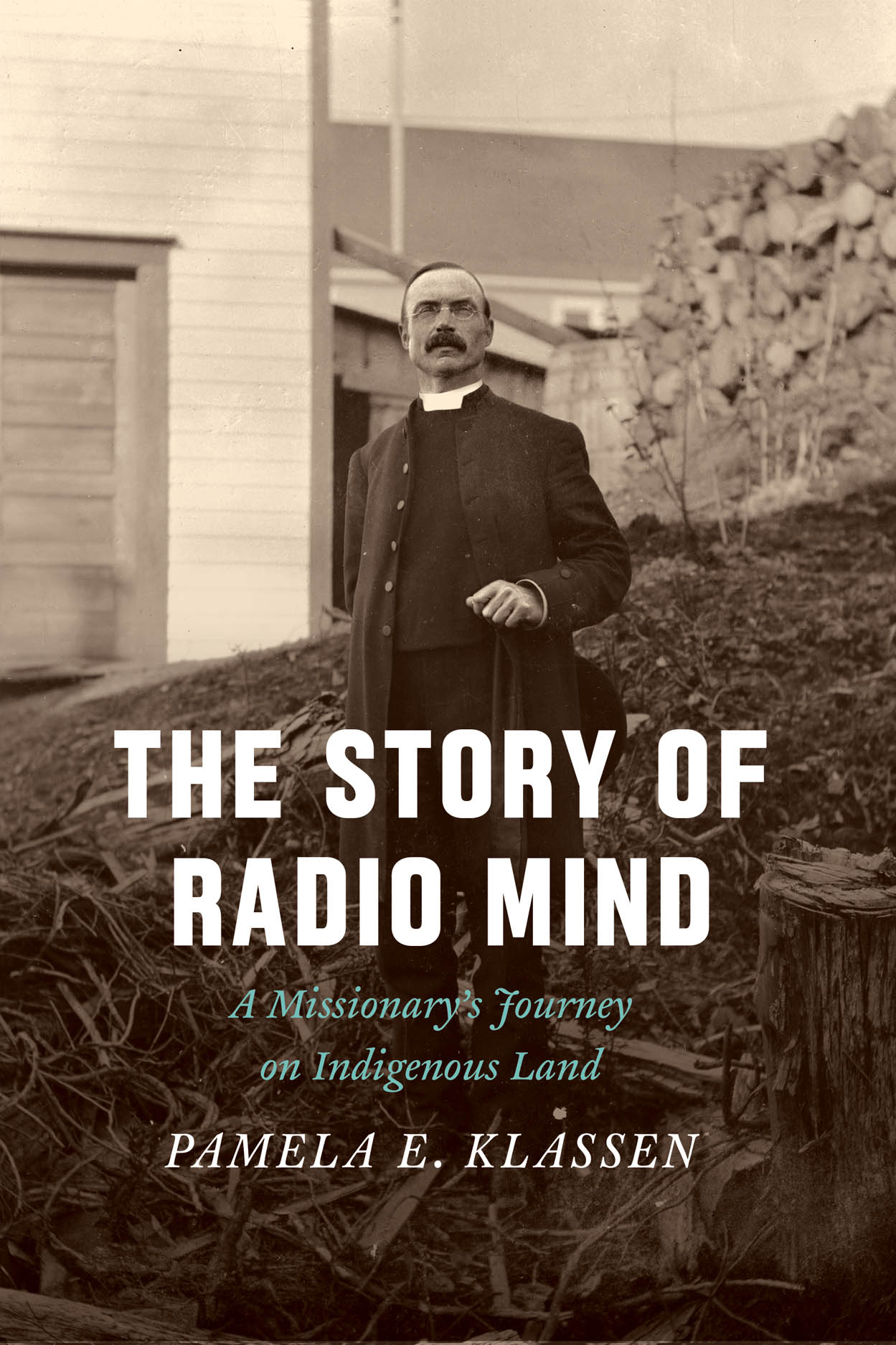

Pamela E. Klassen, The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land, University of Chicago Press, 2018.

read it at Google Books

At the dawn of the radio age in the 1920s, a settler-mystic living on northwest coast of British Columbia invented radio mind: Frederick Du Vernet—Anglican archbishop and self-declared scientist—announced a psychic channel by which minds could telepathically communicate across distance. Retelling Du Vernet’s imaginative experiment, Pamela Klassen shows us how agents of colonialism built metaphysical traditions on land they claimed to have conquered.

Following Du Vernet’s journey westward from Toronto to Ojibwe territory and across the young nation of Canada, Pamela Klassen examines how contests over the mediation of stories—via photography, maps, printing presses, and radio—lucidly reveal the spiritual work of colonial settlement. A city builder who bargained away Indigenous land to make way for the railroad, Du Vernet knew that he lived on the territory of Ts’msyen, Nisga’a, and Haida nations who had never ceded their land to the onrush of Canadian settlers. He condemned the devastating effects on Indigenous families of the residential schools run by his church while still serving that church. Testifying to the power of radio mind with evidence from the apostle Paul and the philosopher Henri Bergson, Du Vernet found a way to explain the world that he, his church and his country made.

Expanding approaches to religion and media studies to ask how sovereignty is made through stories, Klassen shows how the spiritual invention of colonial nations takes place at the same time that Indigenous peoples—including Indigenous Christians—resist colonial dispossession through stories and spirits of their own.

“Deeply researched and thoroughly engaging . . . . Klassen understands Du Vernet and his situation better than he did.” - Reading Religion

“This book tells a tale of love and theft, and it does so with great skill. Every page crackles as it dials into some long-lost channel; radio mind is not only the book’s topic but also suggests its method for investigating the borderlands. Weird and wonderful things are to be found in this twilight zone of psychical research on the imperial margin. Frederick Du Vernet, a heterodox Anglican churchman and one of many philosopher-mystics to find the Pacific coast a happy habitat for spiritual musings, takes telepathic flight with his Pauline psychical research while Native activists whose land he sits on use the printing press to fight for their rights. This stylish and gripping ethnographic biography illuminates colonial contradictions and the spiritual and political resonance of media forms. In offering an affectionate but not exonerating look at a fascinating figure, the book itself participates in the long ambiguous arc toward reconciliation." - John Durham Peters

“The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land is movingly and elegantly written, grounded in thorough and original research in the primary sources, and a powerful study with the makings of a real classic in the field. Klassen not only offers her readers a compelling story; she also layers stories upon stories, and shows us how these stories helped forge the settler colonial nation of Canada. . .Deftly wielding recent theoretical insights from religious studies, indigenous studies, anthropology, and cultural studies, she illuminates the complex and contested power of these stories as mediated through a diverse set of technologies: printing press, totem pole, map, radio, and the experimental psychic technology that her main subject, Archbishop Frederick DuVernet, called “radio mind.” Klassen has produced a book at once accessible, cutting-edge, and profound. . . The Story of Radio Mind is a gift, a major contribution not only to the world of scholarship, but also to all those who seek justice in all the messiness and ambiguities of a settler colonial world. . .Truly the work of a scholar at the top of her form.” - Tisa Wenger

“The Story of Radio Mind is a stunning account. . .Klassen has written a truly innovative book of the intersecting worlds of religion, nationalism, indigeneity, and technology in the late-nineteenth to early-twentieth century. Klassen shows how Du Vernet was transformed by these intersections and how Du Vernet’s encounters with the ‘spiritual energies of the land on which he lived’ impacted his version of Christianity. This book will have wide-ranging appeal to scholars working across a range of fields, including religion, anthropology, and Native American Studies. The Story of Radio Mind contributes to and builds upon a rapidly growing conversation about missionary work and its global implications, while it is also rooted in the local Canadian history of Caledonia.” - Sarah Rivett

Pamela Klassen offers her subtle and judicious book to us “in the spirit” of the call issued in the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report in Canada. Established in 2008 to examine the effects of the Indian Residential Schools, the commission elicited over six thousand testimonies from across the country and mainly from residential school survivors. These survivors, as Klassen poignantly observes, were removed from parents, grandparents, and the elders who might otherwise have told them the stories that held them together as peoples. The commission judged the school system to be a systematic attempt at “cultural genocide.” This is a strong condemnation, especially from a state-sponsored body. The implications of the charge, and the call for action the report issued, have been taken seriously by state and civil institutions in Canada. However, attention has primarily focused on the victims and survivors of the schools, with less attention paid to agents of colonialism, presumably because many of the leading figures are already well represented in Canadian national history. Nonetheless, the relative absence of those voices marks the Canadian TRC as distinct from the South African version, which did consider the stories of perpetrators. In the Canadian context, The Story of Radio Mind flips the script, offering us a dialogic history of settler colonialism.

Rather than place Indigenous survivors of the residential school system at the center, Klassen offers us the vexed figure of Anglican clergyman Frederick Du Vernet (1860-1924), who tracked the westward expansion of white settlement in Canada to become the first Archbishop of Caledonia, a diocese in British Columbia. She does not intend to exonerate him—or the church he represented—from his role in dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their lands, converting them to Christianity, and permitting the removal of Indigenous children to residential schools (a practice he protested, to no avail). Instead, she hopes that exploring the complexity of such a figure, his ambition and his flaws, his compassion and its limits, evokes the spirit of reconciliation. Klassen is not a cynic and, like the TRC commissioners, she believes in the power of stories to change understandings of self and other.

But unlike in the Canadian TRC hearings, Klassen amplifies Du Vernet’s story by taking a dialogic approach and drawing attention to other interpretations of his actions and his assumptions. She does so by laying bare what he could not hear or understand as he crossed Indigenous lands, talked with Indigenous peoples, and undermined their spiritual and material sovereignty. Thus, even when Indigenous voices and actions are excluded from Du Vernet’s own account, Klassen brings them back into the reader’s consciousness.

A significant contribution of Klassen’s approach is to fuse the spiritual with the material: to place the spirit of matter and matters of spirit at the center of her inquiry. Her approach refuses binary distinctions that may be associated with secular historical practice and gives us a much more holistic but no less analytically rich understanding of power. Her primary method for doing so is in drawing the reader’s attention away from semantic content of the array of sources she has collected, focusing instead on the forms of media through which colonization takes place and resistance is issued.

This focus on materiality leads to a second set of interesting, and pressing, questions to which historians of settler colonialism could pay more heed. Examining testimonies, photographs, maps, printing presses, and ultimately Du Vernet’s peculiar notion of “radio mind,” she asks her reader to pay attention to the ethics of making and using these media forms as much as their representational effects. For instance, as she explains in her analysis of photographs of Ojibwe graves, such photographs require “careful handling,” and today Ojibwe communities have successfully persuaded others—including Canadian cultural institutions—of the importance of that ethics of care in using this material.

Radio mind, too, is a medium that requires careful handling. According to Du Vernet, a “mystic of mediation,” radio mind was an immensely powerful force that could bring “the subconscious mind into touch with the Infinite”; or that would, in Klassen’s gloss, “harness[…] vibrations moving through the air,” enabling communication across vast distances. Du Vernet refined the practice of radio mind—a form of telepathy—with his daughter. But in Klassen’s telling radio mind is a metaphor for connection across temporal as well as spatial distance. The idea of radio mind is what grips her imagination when she stumbles across Du Vernet’s whacky theory when flicking through a 1922 edition of the Canadian Churchman and propels her back into the archives to find out more. It is an idea that drives institutional processes of reconciliation, too, a belief that pain caused years even many decades ago can be channeled into the present of narration; that distance—in space, time, even culture or experience—can be crossed and narrowed in the service not just of speaking but of being understood. This belief has a moral character, in the sense that proponents of reconciliation think that being able to cross that distance in order to hear the Other is a good thing.

However, in Klassen’s telling the idea of radio mind is a more ambivalent good. Insofar as radio mind might allow practitioners to read the thoughts of another without leaving home, it is also a measure of the limits of Du Vernet’s self-understanding as well as our own. Some “frequencies” are within our range of hearing and we do not have to move in order to receive them. But many others are not, and if we want to make those frequencies audible we will need to shift position, perhaps quite considerably. But how will we know if we are not hearing something? And what motivates us to orient ourselves to a different frequency?

Projects of reconciliation are often viewed in progressive terms, as processes that will shift national consciousness and understanding from a position of ignorance to one that is more informed, and morally improved. They are institutional responses to activism and public complaint and, in the case of the Canadian TRC, to legal action. They do not come about only because people want them to; there is an element of force in their enactment. That force might be legal, moral, or political, or a mixture of these. The forcefulness driving a state-wide reconciliation project is usually rendered in the terms of national exigency, where the “nation” represents the territorial extent of settler sovereignty—the project of colonization—and now aims to include all those who live within its borders. As the TRC report puts it, reconciliation is an “urgent” task that “must inspire Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples to transform Canadian society so that our children and grandchildren can live together in dignity, peace, and prosperity on these lands we now share.”

Although Du Vernet was upset about the effects of the Indian residential school system, and supported and wrote letters on behalf of Haida, Ts’ymsyen, and Nisga’a, parents he knew who wanted their children back, he was not able to reconcile their needs with those of settlers or, indeed, with his own. As Klassen writes:

https://tif.ssrc.org/2019/03/08/in-the-spirit-of-reconciliation/

The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land is an account of Frederick Du Vernet’s missionary labors in Ontario and British Columbia, from 1898 to 1924, with final attention to his late-in-life embrace of radio as a model and metaphor for trans-regional spiritual connection. At least that is the story suggested by the book’s title. But there is more at stake here than the reconstruction of one man’s journey at the margins of Canadian empire, where he sought to convert Indigenous communities to Anglican Christianity, or the recovery of that man’s marginal notes in publications on psychology and telepathy, where he devised his own philosophy of mind. Much more, indeed.

Pamela Klassen skillfully leads readers to consider important underlying and interconnected concerns throughout The Story of Radio Mind, including occasions of church-state cooperation in Canada, Ojibwe medicinal and burial practices, Ts’msyen and Nisga’a storytelling conventions, land theft and sovereignty claims, intra-Anglican institutional competition, railway building, Indigenous residential schools, trends in psychical research, and the colonial origins of canonical works in academic anthropology. Moreover, readers learn here—in core chapters on photography, map-making, printing presses, and radio—about the ways in which different technologies mediated the spiritual aspirations and effects of Dominion itself, or, as Klassen puts it, how they “were at the heart of the negotiations and contests that made possible the invention of the new Canadian nation.” Operating in multiple registers—and with recurring attention to Klassen’s personal investments in matters of research design and narrative method—The Story of Radio Mind encourages deep reflection on the interdependent relationship between margins and metropoles in North American history and historiography, and it calls scholars to account both for previous failings and future possibilities of self-reflexive storytelling at the intersection of religious studies, Indigenous studies, and media studies.

This is a remarkable book. It is also a difficult book to respond to—and I admit to hours spent staring at blank pages and discarded sentences, before finally writing these. Where might I begin, to do justice to Klassen’s call to consider the stuff and state of religion in technological modernity, alongside also the disciplinary commitments of modern scholarship? Anticipating other responses by people better versed than I in twentieth-century missionary history and sovereignty disputes, not to mention anthropological methods, I have elected to focus first—in the spirit of Klassen’s text and data—on my own marginalia. In particular, I am drawn back to one of the notes that I made while reading The Story of Radio Mind, a banal question that is perhaps also the most pressing: “Is this really a story about radio mind?”

That question came to me several times, especially in the middle chapters of Radio Mind. These include the chapters on photography, wherein Klassen describes Du Vernet’s efforts to stage visual testimonies to Indigenous culture and conversions, the likes of which were often resisted by his would-be subjects; on cartography, wherein we learn how railway surveyors and government agents mapped visions of white settlement and Canadian Dominion onto Indigenous lands, with Du Vernet’s help; and printing presses, the massive “iron pulpits” by which Du Vernet’s missionary contemporaries published accounts of their spiritual successes, but which Indigenous groups also used to contest governmental and corporate offenses against them. Each of these chapters offers a master class in technology and material culture studies for students of religion, especially in contexts of settler colonialism. By this I mean firstly that Klassen pays close attention to the social significance of different media’s physical componentry and productive capacity. She notes, for instance, that—partly because of the bulky equipment involved, as well as its limited technical capacities—white makers of photographs, maps, and newsletters necessarily enlisted Native participation and cooperation, which they sometimes secured and oftentimes did not. (One moment of non-participation, expertly analyzed, was Ojibwe avoidance of Du Vernet’s camera, which Klassen reads not as a function of concerns about “soul-stealing,” per se, but about land-stealing.) Moreover, while such products manifested the mythic aspirations and “imagined communities” of both Christian and Canadian expansionists, they never really erased the Indigenous cartographic or storytelling practices with which they have remained in dynamic tension for generations. In sum, Klassen offers, in these middle chapters, stories about three would-be media of Dominion by or against which missionaries, businessmen, politicians, and Indigenous communities made and contested claims to sovereignty and cultural integrity. Photographs, maps, and newsletters were—despite, or perhaps because of, their affective and effective ambiguities—powerful platforms for religious visions in and of modernity.

How and why is this related to radio mind? At one level, the answer is clear: Du Vernet’s notions of automatic thought transference, inspired by the idea if not also the mechanics of radio, was the last in a series of technophilic dreams for the spiritual connection of Canada’s margins and metropoles. More than that, Du Vernet considered radio mind to be the rightful means of global sympathy and social justice, the likes of which would pacify otherwise discordant relations—including perhaps those wrought by his and his colleagues’ earlier frontier experiments with technology. Radio mind was the culmination of his life’s work, according to Du Vernet, and Klassen likewise announces it as a cumulative horizon for her book’s interpretive labors.

But radio mind was different than photo-imagination, map-mind, or print-perception (if you will) not only in terms of its developmental chronology or utopian aspirations, but also with respect to its place and placelessness in the Indigenous communities of Du Vernet’s erstwhile concern. By this I mean, in part, that Du Vernet developed his theories of radio mind while reading books written by Henri Bergson, William James, and other white men, in imaginary conversation with immediate white family members, and in essays intended for a white Anglican readership. Not only that, but—perhaps bolstered by a dissociation from actual radio mechanics and networks, the likes of which may have permitted Du Vernet to perceive or maintain certain distinctions between his “white work” and “Indigenous work”—Du Vernet did not explicitly develop or apply radio mind in conversation with Indigenous communicants or in matters of Indigenous welfare. This need not be read as tragic, necessarily, given the violence of previous attempts to enlist Indigenous people as subjects or agents of new media. But Klassen does see in it a certain missed opportunity, nonetheless, insofar as Du Vernet’s late life was otherwise characterized by increasing concern with and opposition to contemporaneous church-state alliances and boarding school initiatives that threatened Native communities. Du Vernet’s “scientific” reflections and “episcopal” critiques were separated by mere moments in his life and mere pages in his diary.

What if he had connected them? What if Du Vernet had developed or applied radio mind’s egalitarian impulses relative to the social concerns that otherwise enveloped him? Alternately, what if he had sought “a spiritual current that would bind together across people, spirits, and the energy of love” in “legislation or church lobbying” as much as in “scientific experiment”? Du Vernet did neither and instead kept his interests and outlets separate. Klassen suggests, therefore, that radio mind, for all of its well-intentioned “intensity,” was characterized more by “inconsistency” and indeed “failure” when it came to being “a tool of healing in the midst of the piercing violence of family annihilation, cultural genocide, and church and state deceit that was the residential school system.”

Historians of religion are familiar with problems of archival disconnection and silence, not to mention the willful avoidance of integrative thought and self-reflection, especially with respect to Indigenous-white interaction and influence. Klassen skillfully reads into these gaps throughout this book, rightly refusing to allow certain subjects’ insistence on categorical distinctions to preclude deep analysis into their mechanical and affective relations. But one reason why the story of radio mind first struck me as different than the story of photography or the like, at least in terms of its telling, is that Klassen’s approach to gap-reading is somewhat distinct here. If earlier chapters sought to recover the technologies by which colonial populations were simultaneously divided and connected, this last section (on my reading) attends more to the ways in which technological metaphors can themselves work with or against such networked awareness in history and the modern academy. Both approaches suggest new ways forward in the study of religion and/in modernity, and both demonstrate, in different ways, how modernity is co-producing of both indigeneity and Indigenous studies. But it is noteworthy that Klassen’s chapter on “frequencies for listening” begins by tacking more closely with Du Vernet’s own inclination to engage with radio mind and religious studies alike through metaphor and morphology, intellectual history and philosophical association. By the end of this chapter Klassen also will challenge Du Vernet’s desire—as well as contemporary scholarly inclinations—to hold separate the stuff of religion and politics, thought and discipline, study and activism. Klassen morphs metaphors (back) into networks. But I do not want to get ahead of her too much, nor indeed to jump too quickly over my sense of a narrative or methodological shift here, as Klassen experiments with a different route through archival silences to scholarly connections.

What I am pointing to is the fact that, when seeking the unspoken connections between Du Vernet’s ostensibly parallel concerns of psychic communication networks and the networks of Native (re)education, Klassen embarks not on a story of radio’s colonial circuitry, as she might have in the middle chapters, but instead questions whether radio mind itself might have philosophical or intellectual affinities with Indigenous theories and ways of knowing. Put differently, Klassen asks whether “Du Vernet’s spiritual imagination” demonstrated influence by or sympathy with Indigenous peoples’ “spiritual conditions and practices of spiritual communication,” even when Du Vernet refused to name them as such—let alone to engage them in relation to politics. This is a difficult question to answer. Du Vernet did not need much beyond Bergson and company to develop a theory about the nature of radio mind, just as “Du Vernet did not need radio mind to reach” certain conclusions about the wrongheadedness of his church and country’s boarding school plan. Klassen readily acknowledges this, even as she knows well the dangers of accepting at face value any writings, from any colonial context, where authors make little mention of Native presence and influence. People think always in relation to the networks in which they move, regardless of whether they acknowledge as much.

Klassen thus invites us to undertake a thought experiment alongside Du Vernet’s thought experiment: to think critically and creatively about the materials that do and do not reveal the complexities of human connection; and to consider morphology as well as materiality as grounds for scholarly re-engagement. If archives are always partial and scholarly connections are always partly imaginary, as they are, then Klassen discovers in radio mind her own kind of metaphor for finding—and finding sympathy with—sources that we don’t always have, and which are seldom announced to be in direct connection anyway. Such findings are meritorious insofar as they then reconnect us to material conditions and spiritual concerns of the moment, as well as to those of our present. Thus whereas Du Vernet eschewed explicit consultation with Indigenous thinkers when developing a theory of modern religiosity—and whereas he resisted connecting his theoretical and political concerns, as well—would-be postcolonial and decolonial scholars have no such option. We would do well both to network and broadcast our disciplinary commitments, according to Klassen’s model.

“Is this really a story about radio mind?” I thought not, on first reading, insofar as radio mind is the obvious stuff and substance of only the concluding chapters of Du Vernet’s life as well as Klassen’s book, and Klassen’s approach there is somewhat different than in other chapters. But in another sense—and a greater register—the answer is decidedly yes. For, The Story of Radio Mind is a story of Klassen’s own coming into sympathy with and alongside Du Vernet’s coming into sympathy, even as it questions the grounds and applications of the latter, and while it offers up both in the spirit of reconciliation. This is a tough act to follow, and, like me, other scholars may find themselves staring at blank pages for some time before beginning to write anew. Not least because, when doing so, they/we will need to be as attentive as Klassen is to the difference between potlach and confession, to ensure that all “incitements to discourse” in archival gaps do not (re)produce more predictable and problematic assertions about Native culture, ontologies, spiritualities, and the like. Thankfully, Klassen has offered one such model, and for that I am very grateful. She charts a way forward, and I am eager to see where she, her students, and the greater field go next. - David Walker

https://tif.ssrc.org/2019/03/08/the-discipline-of-radio-mind/

I am grateful to both Miranda Johnson and David Walker for reading The Story of Radio Mind with such generosity and attention, and for their astute comments on the theoretical and methodological interventions that I hoped would be transmitted in its telling. Their critical readings reveal the truth voiced by Walker: “People think always in relation to the networks in which they move.”

Walker’s research moves on a track parallel to my own. In his work on the building of the railroad in nineteenth-century Utah, on Shoshone and Ute land, he denaturalizes the seemingly secular bottom line of business, entrepreneurialism, and technology. To borrow his words about The Story of Radio Mind, in his own work Walker shows how Mormon settlers, entrepreneurs, missionaries, “railway surveyors and government agents mapped visions of white settlement.” He coins the phrase “would-be media of Dominion” to frame my argument about cosmologies of mediation: namely that the communication technologies of photography, printing presses, maps, and radio were tools of missionary-colonial modernity. He so handily receives and rearticulates the point of my book because it resonates with his own—grown out of other networks, on different land.

From another vantage point and set of networks also within range of my own, Johnson writes from her perspective of living and working in a “Commonwealth” settler-colonial state. In her book, The Land is Our History, Johnson shows how post-1960s Indigenous activism and legal challenges in Aoteoroa/New Zealand, Australia, and Canada were remarkably successful in challenging the “founding story of the settler state.” Johnson has reflected with great insight on the seemingly endless task of trying to figure out what one does, as a scholar, in the wake of the realization that the land on which one lives and works is both settled and stolen; that to write any stories of such land requires seeking out and listening to Indigenous narratives, and changing the settled stories in response. So, when she notes that I am “not a cynic” when it comes to thinking about reconciliation and its promises and failures, my sense is that she is not suggesting the opposite, that I am abounding with credulity.

The line between critique and credulity, or between cynicism and naiveté, is at the heart of all of the books in this forum on “modernity’s resonances.” My tack on this question follows one man on his journey from east to west, beginning on Abenaki land, which was claimed in the seventeenth century by the French Crown and then in the eighteenth century by the British Crown. As a young man, Frederick Du Vernet found his networks among Anglican clergy and the Anglo-Canadian elite in Toronto, on land bound by treaties between the Anishinaabeg, the Haudenosaunee, and the British Crown. In mid-life, he ventured to the unceded territories of the Haida, Nisga’a, and Ts’msyen on the Pacific Northwest coast, where his networks expanded in two different ways. First, as a white missionary bishop living among a predominantly Indigenous population, he learned about the diversity of their languages and forms of property, their stories of creation, and their resistance to land dispossession and to state pressure to send their children to church-run residential schools.

Then late in life and in the wake of a devastating world war, as a man coming to understand himself as at once modern, scientific, and spiritual, he entered into a publishing network of psychic researchers. He read books by men of intellectual renown including William James and Henri Bergson, who voiced anxieties about credulity while articulating profound hope for the power of telepathy and “mind energy” with worldwide effects. Embedding these psychic narratives within Christian theological commitments, he came to write with considerable confidence, and seemingly little anxiety, about having proved the power of what he called radio mind.

As the other books in this forum show, psychic research and its affiliates, such as mesmerism, magic, and later on, extraterrestrial speculation, exemplify how telling the story of modernity’s resonances requires tracing the paths of colonial resource extraction, slavery, and land dispossession. Indigenous responses to and rejection of such dispossession are also part of the story. I set Du Vernet’s “technophilic” story at this nexus of specifically emplaced and ongoing Nisga’a, Ts’msyen, and Haida land movements in the Pacific Northwest and a traveling network of intellectual and spiritual exploration with varied colonial currents.

As Walker notes, I point repeatedly to the significance of storytelling in terms of the materiality and physicality of different forms of mediation (e.g., dry-plate photography) and the ethics of relationality embedded within these different forms. In doing so, I draw not only from recent discussions of religion and mediation, but also from arguments of Indigenous novelists and scholars about the significance of storytelling as theory, method, and protocol (codes of behavior). Storytelling is always shaped by protocols of address and relationality. Learning this, I also realized that how I would tell The Story of Radio Mind was as much shaped by visiting archives as it was by my experience of telling stories to my children and of talking with Nisga’a and Ojibwe elders and historical experts.

Walker is very right that The Story of Radio Mind does not qualify as an encyclopedic title, since I only dive deeply into the radio mind part of the story in the last two chapters. As I thought about what form the book might take, I decided that I could not consider radio mind until I explained the earlier places and times in Du Vernet’s journey. I also decided that I could not tell the story if I did not venture to those same places and speak to some of the people who live there today. My travels with students and family members to the Rainy River First Nations, the Nisga’a Nation, the Ts’msyen First Nation at Metlakatla, and to Du Vernet’s episcopal seat in Prince Rupert (among other places) became part of the story of radio mind. The Ojibwe, Nisga’a, and Ts’msyen communities I visited had no memories of Frederick Du Vernet, but they did tell stories of other Christian missionaries and of the “Indian Land Movement” in museums, books, and other documents. After bringing Du Vernet’s diary of his visit to the Rainy River in 1898 to the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre, I have since worked with students and community members from the Rainy River First Nations to remediate the diary as an interactive website Kiinawin Kawindomowin Story Nations.

Like Walker, Johnson also points to my persistent focus on the material forms of cosmologies of mediation, characterizing my approach more boldly than I did: “to fuse the spiritual with the material: to place the spirit of matter and matters of spirit at the center of her inquiry.” Similarly, reflecting on radio mind as a metaphor when pondering the fraught concept of reconciliation, she articulates the point of my book in ways that I did not see: “Some ‘frequencies’ are within our range of hearing and we do not have to move in order to receive them. But many others are not, and if we want to make those frequencies audible we will need to shift position, perhaps quite considerably. But how will we know if we are not hearing something? And what motivates us to orient ourselves to a different frequency?” Pointing out the political stakes of what she calls the “conditions of audibility” Johnson gets to the vulnerability of any theoretical—or spiritual—claim: if no one can hear or understand it, it will resonate with no one.

As Johnson makes clear, despite the “facticity” of colonial violence and dispossession and of the persistence of Indigenous refusal of such violence and dispossession, within settler states there are many doubters and deniers of these facts, including many scholars. It is no wonder then, as she points out, that many who do accept that facticity have rejected the concept and project of reconciliation as a “liberal ruse” that tries to “redeem” the settler state by way of a different story.

Framed in the terms of this forum, one of my primary aims in writing this book was to document how Indigenous land movements that countered and, following Audra Simpson, refused colonialism are also among the resonances of modernity. Instead of finding anxieties about credulity or naiveté when reading the stories, ripostes, and petitions of Indigenous people contesting colonialism, however, I found resolute calls to spiritual authority—both Indigenous and Christian—to claim their ground. As Nisga’a Chief Timothy Derrick put it to an Indian Agent in 1908, and as I relay in the book, the chiefs rejected the authority of the Canadian Indian Act and the Indian Agent, along with the very idea of an Indian reserve: “We have come to the conclusion therefore that it is much better for us to try to hold of ourselves the inheritance which God gave our fathers at the beginning.” Indigenous peoples continue to frame their sovereignty as a gift from the Creator, with little care for whether or not such a claim resonated with colonial secular governance. For hundreds of years, Indigenous peoples have been remarkably consistent in referring to their ongoing spiritual jurisdiction in their petitions and legal cases directed at representatives of the Crown in Canada and elsewhere.

Indigenous refusal of colonial sovereignty has long recognized the spiritual vulnerability of colonial settlement. Indigenous leaders such as Derrick regularly clarified to colonial officials that the Crown’s claims to own the land were rooted not in secular law but in Christian doctrines of discovery. They also repeatedly used such doctrines to call to account the Dominion government, whether citing biblical injunctions to not “remove thy neighbour’s landmark” or referencing King George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763.

The spiritual vulnerability of colonial settlement, I would argue, is one important reason why both Christian and secular condemnations of credulity and superstition have long been so anxious, and so resonant, in colonial modernity. As the persistence of Indigenous spiritual jurisdiction shows, however, even if those living in settler-colonial states use concepts such as property, law, and secular reason to close their ears to the steady hum of Indigenous presence on the land, the vibrations refuse to go away. - Pamela E. Klassen

tif.ssrc.org/2019/03/08/networks-of-reception-conditions-of-audibility/#.XIPBBVuprZI.twitter

Pamela Klassen offers her subtle and judicious book to us “in the spirit” of the call issued in the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report in Canada. Established in 2008 to examine the effects of the Indian Residential Schools, the commission elicited over six thousand testimonies from across the country and mainly from residential school survivors. These survivors, as Klassen poignantly observes, were removed from parents, grandparents, and the elders who might otherwise have told them the stories that held them together as peoples. The commission judged the school system to be a systematic attempt at “cultural genocide.” This is a strong condemnation, especially from a state-sponsored body. The implications of the charge, and the call for action the report issued, have been taken seriously by state and civil institutions in Canada. However, attention has primarily focused on the victims and survivors of the schools, with less attention paid to agents of colonialism, presumably because many of the leading figures are already well represented in Canadian national history. Nonetheless, the relative absence of those voices marks the Canadian TRC as distinct from the South African version, which did consider the stories of perpetrators. In the Canadian context, The Story of Radio Mind flips the script, offering us a dialogic history of settler colonialism.

Rather than place Indigenous survivors of the residential school system at the center, Klassen offers us the vexed figure of Anglican clergyman Frederick Du Vernet (1860-1924), who tracked the westward expansion of white settlement in Canada to become the first Archbishop of Caledonia, a diocese in British Columbia. She does not intend to exonerate him—or the church he represented—from his role in dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their lands, converting them to Christianity, and permitting the removal of Indigenous children to residential schools (a practice he protested, to no avail). Instead, she hopes that exploring the complexity of such a figure, his ambition and his flaws, his compassion and its limits, evokes the spirit of reconciliation. Klassen is not a cynic and, like the TRC commissioners, she believes in the power of stories to change understandings of self and other.

But unlike in the Canadian TRC hearings, Klassen amplifies Du Vernet’s story by taking a dialogic approach and drawing attention to other interpretations of his actions and his assumptions. She does so by laying bare what he could not hear or understand as he crossed Indigenous lands, talked with Indigenous peoples, and undermined their spiritual and material sovereignty. Thus, even when Indigenous voices and actions are excluded from Du Vernet’s own account, Klassen brings them back into the reader’s consciousness.

A significant contribution of Klassen’s approach is to fuse the spiritual with the material: to place the spirit of matter and matters of spirit at the center of her inquiry. Her approach refuses binary distinctions that may be associated with secular historical practice and gives us a much more holistic but no less analytically rich understanding of power. Her primary method for doing so is in drawing the reader’s attention away from semantic content of the array of sources she has collected, focusing instead on the forms of media through which colonization takes place and resistance is issued.

This focus on materiality leads to a second set of interesting, and pressing, questions to which historians of settler colonialism could pay more heed. Examining testimonies, photographs, maps, printing presses, and ultimately Du Vernet’s peculiar notion of “radio mind,” she asks her reader to pay attention to the ethics of making and using these media forms as much as their representational effects. For instance, as she explains in her analysis of photographs of Ojibwe graves, such photographs require “careful handling,” and today Ojibwe communities have successfully persuaded others—including Canadian cultural institutions—of the importance of that ethics of care in using this material.

Radio mind, too, is a medium that requires careful handling. According to Du Vernet, a “mystic of mediation,” radio mind was an immensely powerful force that could bring “the subconscious mind into touch with the Infinite”; or that would, in Klassen’s gloss, “harness[…] vibrations moving through the air,” enabling communication across vast distances. Du Vernet refined the practice of radio mind—a form of telepathy—with his daughter. But in Klassen’s telling radio mind is a metaphor for connection across temporal as well as spatial distance. The idea of radio mind is what grips her imagination when she stumbles across Du Vernet’s whacky theory when flicking through a 1922 edition of the Canadian Churchman and propels her back into the archives to find out more. It is an idea that drives institutional processes of reconciliation, too, a belief that pain caused years even many decades ago can be channeled into the present of narration; that distance—in space, time, even culture or experience—can be crossed and narrowed in the service not just of speaking but of being understood. This belief has a moral character, in the sense that proponents of reconciliation think that being able to cross that distance in order to hear the Other is a good thing.

However, in Klassen’s telling the idea of radio mind is a more ambivalent good. Insofar as radio mind might allow practitioners to read the thoughts of another without leaving home, it is also a measure of the limits of Du Vernet’s self-understanding as well as our own. Some “frequencies” are within our range of hearing and we do not have to move in order to receive them. But many others are not, and if we want to make those frequencies audible we will need to shift position, perhaps quite considerably. But how will we know if we are not hearing something? And what motivates us to orient ourselves to a different frequency?

Projects of reconciliation are often viewed in progressive terms, as processes that will shift national consciousness and understanding from a position of ignorance to one that is more informed, and morally improved. They are institutional responses to activism and public complaint and, in the case of the Canadian TRC, to legal action. They do not come about only because people want them to; there is an element of force in their enactment. That force might be legal, moral, or political, or a mixture of these. The forcefulness driving a state-wide reconciliation project is usually rendered in the terms of national exigency, where the “nation” represents the territorial extent of settler sovereignty—the project of colonization—and now aims to include all those who live within its borders. As the TRC report puts it, reconciliation is an “urgent” task that “must inspire Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples to transform Canadian society so that our children and grandchildren can live together in dignity, peace, and prosperity on these lands we now share.”

Although Du Vernet was upset about the effects of the Indian residential school system, and supported and wrote letters on behalf of Haida, Ts’ymsyen, and Nisga’a, parents he knew who wanted their children back, he was not able to reconcile their needs with those of settlers or, indeed, with his own. As Klassen writes:

Hearing in one ear the bitter cry of the settlers who wanted schools for their children, Du Vernet heard in the other one similar anguished petitions from Indigenous parents. At a certain frequency, he understood that both these cries were related to the underlying fact of colonial dispossession and capitalist speculation. But he never quite put the two together.Klassen is better able to put the two pleas together by deploying a theory of settler colonialism. This theory explains the distinctiveness of colonization in settler societies as driven by settlers’ need for land, which results in the “replacing” or even elimination (culturally if not physically) of Indigenous peoples on their own lands. She is drawing broadly on ideas associated with the Australian historian Patrick Wolfe, who developed his thinking about settler colonialism in a series of books and articles over the last two decades—however, unlike many theorists in the field, she takes account of the experiences of settlers themselves.1 Among the broad grouping of settlers today are a range of opinions on colonialism and its effects. Not everyone in settler states agrees that the “underlying fact of colonial dispossession” is as well-founded as Klassen assumes. Critics exert considerable energy in contradicting such facts or even denying their facticity. In Canada and Australia, where I work, some conservative historians, public figures, and politicians have pushed back against what they see as overly sympathetic representations of Indigenous grievances by liberal historians they argue are more concerned with making political points than sticking to the facts they approve. These “history wars” have directly influenced the design and delivery of school curricula. Public conflict has also impacted Indigenous communities, whom one Australian anthropologist has pointed out are the “collateral damage” of such bruising controversies.2 The strongest exponents of “denialism,” history “warriors” who abhor the politicizing of facts of dispossession, consider the “spirit” of reconciliation a liberal ruse and they refuse to be duped. They will not hear otherwise, or orient themselves to another frequency. No doubt their refusal expresses a complex pattern of belief and practice, matter and spirit, ethics and politics, that could itself be analyzed using the methods deployed by Klassen. The Story of Radio Mind asks us to pay attention to how hearing the Other is contingent on material, historical, and even personal conditions of audibility. By drawing on that method, we might consider how the “Other” is not only the colonized Indigenous figure but also the political opponent of reconciliation. Klassen therefore invites us into murkier political territory where we cannot take the conditions for listening for granted. We would do well to think more carefully about how such conditions come about. - Miranda Johnson

https://tif.ssrc.org/2019/03/08/in-the-spirit-of-reconciliation/

The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land is an account of Frederick Du Vernet’s missionary labors in Ontario and British Columbia, from 1898 to 1924, with final attention to his late-in-life embrace of radio as a model and metaphor for trans-regional spiritual connection. At least that is the story suggested by the book’s title. But there is more at stake here than the reconstruction of one man’s journey at the margins of Canadian empire, where he sought to convert Indigenous communities to Anglican Christianity, or the recovery of that man’s marginal notes in publications on psychology and telepathy, where he devised his own philosophy of mind. Much more, indeed.

Pamela Klassen skillfully leads readers to consider important underlying and interconnected concerns throughout The Story of Radio Mind, including occasions of church-state cooperation in Canada, Ojibwe medicinal and burial practices, Ts’msyen and Nisga’a storytelling conventions, land theft and sovereignty claims, intra-Anglican institutional competition, railway building, Indigenous residential schools, trends in psychical research, and the colonial origins of canonical works in academic anthropology. Moreover, readers learn here—in core chapters on photography, map-making, printing presses, and radio—about the ways in which different technologies mediated the spiritual aspirations and effects of Dominion itself, or, as Klassen puts it, how they “were at the heart of the negotiations and contests that made possible the invention of the new Canadian nation.” Operating in multiple registers—and with recurring attention to Klassen’s personal investments in matters of research design and narrative method—The Story of Radio Mind encourages deep reflection on the interdependent relationship between margins and metropoles in North American history and historiography, and it calls scholars to account both for previous failings and future possibilities of self-reflexive storytelling at the intersection of religious studies, Indigenous studies, and media studies.

This is a remarkable book. It is also a difficult book to respond to—and I admit to hours spent staring at blank pages and discarded sentences, before finally writing these. Where might I begin, to do justice to Klassen’s call to consider the stuff and state of religion in technological modernity, alongside also the disciplinary commitments of modern scholarship? Anticipating other responses by people better versed than I in twentieth-century missionary history and sovereignty disputes, not to mention anthropological methods, I have elected to focus first—in the spirit of Klassen’s text and data—on my own marginalia. In particular, I am drawn back to one of the notes that I made while reading The Story of Radio Mind, a banal question that is perhaps also the most pressing: “Is this really a story about radio mind?”

That question came to me several times, especially in the middle chapters of Radio Mind. These include the chapters on photography, wherein Klassen describes Du Vernet’s efforts to stage visual testimonies to Indigenous culture and conversions, the likes of which were often resisted by his would-be subjects; on cartography, wherein we learn how railway surveyors and government agents mapped visions of white settlement and Canadian Dominion onto Indigenous lands, with Du Vernet’s help; and printing presses, the massive “iron pulpits” by which Du Vernet’s missionary contemporaries published accounts of their spiritual successes, but which Indigenous groups also used to contest governmental and corporate offenses against them. Each of these chapters offers a master class in technology and material culture studies for students of religion, especially in contexts of settler colonialism. By this I mean firstly that Klassen pays close attention to the social significance of different media’s physical componentry and productive capacity. She notes, for instance, that—partly because of the bulky equipment involved, as well as its limited technical capacities—white makers of photographs, maps, and newsletters necessarily enlisted Native participation and cooperation, which they sometimes secured and oftentimes did not. (One moment of non-participation, expertly analyzed, was Ojibwe avoidance of Du Vernet’s camera, which Klassen reads not as a function of concerns about “soul-stealing,” per se, but about land-stealing.) Moreover, while such products manifested the mythic aspirations and “imagined communities” of both Christian and Canadian expansionists, they never really erased the Indigenous cartographic or storytelling practices with which they have remained in dynamic tension for generations. In sum, Klassen offers, in these middle chapters, stories about three would-be media of Dominion by or against which missionaries, businessmen, politicians, and Indigenous communities made and contested claims to sovereignty and cultural integrity. Photographs, maps, and newsletters were—despite, or perhaps because of, their affective and effective ambiguities—powerful platforms for religious visions in and of modernity.

How and why is this related to radio mind? At one level, the answer is clear: Du Vernet’s notions of automatic thought transference, inspired by the idea if not also the mechanics of radio, was the last in a series of technophilic dreams for the spiritual connection of Canada’s margins and metropoles. More than that, Du Vernet considered radio mind to be the rightful means of global sympathy and social justice, the likes of which would pacify otherwise discordant relations—including perhaps those wrought by his and his colleagues’ earlier frontier experiments with technology. Radio mind was the culmination of his life’s work, according to Du Vernet, and Klassen likewise announces it as a cumulative horizon for her book’s interpretive labors.

But radio mind was different than photo-imagination, map-mind, or print-perception (if you will) not only in terms of its developmental chronology or utopian aspirations, but also with respect to its place and placelessness in the Indigenous communities of Du Vernet’s erstwhile concern. By this I mean, in part, that Du Vernet developed his theories of radio mind while reading books written by Henri Bergson, William James, and other white men, in imaginary conversation with immediate white family members, and in essays intended for a white Anglican readership. Not only that, but—perhaps bolstered by a dissociation from actual radio mechanics and networks, the likes of which may have permitted Du Vernet to perceive or maintain certain distinctions between his “white work” and “Indigenous work”—Du Vernet did not explicitly develop or apply radio mind in conversation with Indigenous communicants or in matters of Indigenous welfare. This need not be read as tragic, necessarily, given the violence of previous attempts to enlist Indigenous people as subjects or agents of new media. But Klassen does see in it a certain missed opportunity, nonetheless, insofar as Du Vernet’s late life was otherwise characterized by increasing concern with and opposition to contemporaneous church-state alliances and boarding school initiatives that threatened Native communities. Du Vernet’s “scientific” reflections and “episcopal” critiques were separated by mere moments in his life and mere pages in his diary.

What if he had connected them? What if Du Vernet had developed or applied radio mind’s egalitarian impulses relative to the social concerns that otherwise enveloped him? Alternately, what if he had sought “a spiritual current that would bind together across people, spirits, and the energy of love” in “legislation or church lobbying” as much as in “scientific experiment”? Du Vernet did neither and instead kept his interests and outlets separate. Klassen suggests, therefore, that radio mind, for all of its well-intentioned “intensity,” was characterized more by “inconsistency” and indeed “failure” when it came to being “a tool of healing in the midst of the piercing violence of family annihilation, cultural genocide, and church and state deceit that was the residential school system.”

Historians of religion are familiar with problems of archival disconnection and silence, not to mention the willful avoidance of integrative thought and self-reflection, especially with respect to Indigenous-white interaction and influence. Klassen skillfully reads into these gaps throughout this book, rightly refusing to allow certain subjects’ insistence on categorical distinctions to preclude deep analysis into their mechanical and affective relations. But one reason why the story of radio mind first struck me as different than the story of photography or the like, at least in terms of its telling, is that Klassen’s approach to gap-reading is somewhat distinct here. If earlier chapters sought to recover the technologies by which colonial populations were simultaneously divided and connected, this last section (on my reading) attends more to the ways in which technological metaphors can themselves work with or against such networked awareness in history and the modern academy. Both approaches suggest new ways forward in the study of religion and/in modernity, and both demonstrate, in different ways, how modernity is co-producing of both indigeneity and Indigenous studies. But it is noteworthy that Klassen’s chapter on “frequencies for listening” begins by tacking more closely with Du Vernet’s own inclination to engage with radio mind and religious studies alike through metaphor and morphology, intellectual history and philosophical association. By the end of this chapter Klassen also will challenge Du Vernet’s desire—as well as contemporary scholarly inclinations—to hold separate the stuff of religion and politics, thought and discipline, study and activism. Klassen morphs metaphors (back) into networks. But I do not want to get ahead of her too much, nor indeed to jump too quickly over my sense of a narrative or methodological shift here, as Klassen experiments with a different route through archival silences to scholarly connections.

What I am pointing to is the fact that, when seeking the unspoken connections between Du Vernet’s ostensibly parallel concerns of psychic communication networks and the networks of Native (re)education, Klassen embarks not on a story of radio’s colonial circuitry, as she might have in the middle chapters, but instead questions whether radio mind itself might have philosophical or intellectual affinities with Indigenous theories and ways of knowing. Put differently, Klassen asks whether “Du Vernet’s spiritual imagination” demonstrated influence by or sympathy with Indigenous peoples’ “spiritual conditions and practices of spiritual communication,” even when Du Vernet refused to name them as such—let alone to engage them in relation to politics. This is a difficult question to answer. Du Vernet did not need much beyond Bergson and company to develop a theory about the nature of radio mind, just as “Du Vernet did not need radio mind to reach” certain conclusions about the wrongheadedness of his church and country’s boarding school plan. Klassen readily acknowledges this, even as she knows well the dangers of accepting at face value any writings, from any colonial context, where authors make little mention of Native presence and influence. People think always in relation to the networks in which they move, regardless of whether they acknowledge as much.

Klassen thus invites us to undertake a thought experiment alongside Du Vernet’s thought experiment: to think critically and creatively about the materials that do and do not reveal the complexities of human connection; and to consider morphology as well as materiality as grounds for scholarly re-engagement. If archives are always partial and scholarly connections are always partly imaginary, as they are, then Klassen discovers in radio mind her own kind of metaphor for finding—and finding sympathy with—sources that we don’t always have, and which are seldom announced to be in direct connection anyway. Such findings are meritorious insofar as they then reconnect us to material conditions and spiritual concerns of the moment, as well as to those of our present. Thus whereas Du Vernet eschewed explicit consultation with Indigenous thinkers when developing a theory of modern religiosity—and whereas he resisted connecting his theoretical and political concerns, as well—would-be postcolonial and decolonial scholars have no such option. We would do well both to network and broadcast our disciplinary commitments, according to Klassen’s model.

“Is this really a story about radio mind?” I thought not, on first reading, insofar as radio mind is the obvious stuff and substance of only the concluding chapters of Du Vernet’s life as well as Klassen’s book, and Klassen’s approach there is somewhat different than in other chapters. But in another sense—and a greater register—the answer is decidedly yes. For, The Story of Radio Mind is a story of Klassen’s own coming into sympathy with and alongside Du Vernet’s coming into sympathy, even as it questions the grounds and applications of the latter, and while it offers up both in the spirit of reconciliation. This is a tough act to follow, and, like me, other scholars may find themselves staring at blank pages for some time before beginning to write anew. Not least because, when doing so, they/we will need to be as attentive as Klassen is to the difference between potlach and confession, to ensure that all “incitements to discourse” in archival gaps do not (re)produce more predictable and problematic assertions about Native culture, ontologies, spiritualities, and the like. Thankfully, Klassen has offered one such model, and for that I am very grateful. She charts a way forward, and I am eager to see where she, her students, and the greater field go next. - David Walker

https://tif.ssrc.org/2019/03/08/the-discipline-of-radio-mind/

I am grateful to both Miranda Johnson and David Walker for reading The Story of Radio Mind with such generosity and attention, and for their astute comments on the theoretical and methodological interventions that I hoped would be transmitted in its telling. Their critical readings reveal the truth voiced by Walker: “People think always in relation to the networks in which they move.”

Walker’s research moves on a track parallel to my own. In his work on the building of the railroad in nineteenth-century Utah, on Shoshone and Ute land, he denaturalizes the seemingly secular bottom line of business, entrepreneurialism, and technology. To borrow his words about The Story of Radio Mind, in his own work Walker shows how Mormon settlers, entrepreneurs, missionaries, “railway surveyors and government agents mapped visions of white settlement.” He coins the phrase “would-be media of Dominion” to frame my argument about cosmologies of mediation: namely that the communication technologies of photography, printing presses, maps, and radio were tools of missionary-colonial modernity. He so handily receives and rearticulates the point of my book because it resonates with his own—grown out of other networks, on different land.

From another vantage point and set of networks also within range of my own, Johnson writes from her perspective of living and working in a “Commonwealth” settler-colonial state. In her book, The Land is Our History, Johnson shows how post-1960s Indigenous activism and legal challenges in Aoteoroa/New Zealand, Australia, and Canada were remarkably successful in challenging the “founding story of the settler state.” Johnson has reflected with great insight on the seemingly endless task of trying to figure out what one does, as a scholar, in the wake of the realization that the land on which one lives and works is both settled and stolen; that to write any stories of such land requires seeking out and listening to Indigenous narratives, and changing the settled stories in response. So, when she notes that I am “not a cynic” when it comes to thinking about reconciliation and its promises and failures, my sense is that she is not suggesting the opposite, that I am abounding with credulity.

The line between critique and credulity, or between cynicism and naiveté, is at the heart of all of the books in this forum on “modernity’s resonances.” My tack on this question follows one man on his journey from east to west, beginning on Abenaki land, which was claimed in the seventeenth century by the French Crown and then in the eighteenth century by the British Crown. As a young man, Frederick Du Vernet found his networks among Anglican clergy and the Anglo-Canadian elite in Toronto, on land bound by treaties between the Anishinaabeg, the Haudenosaunee, and the British Crown. In mid-life, he ventured to the unceded territories of the Haida, Nisga’a, and Ts’msyen on the Pacific Northwest coast, where his networks expanded in two different ways. First, as a white missionary bishop living among a predominantly Indigenous population, he learned about the diversity of their languages and forms of property, their stories of creation, and their resistance to land dispossession and to state pressure to send their children to church-run residential schools.

Then late in life and in the wake of a devastating world war, as a man coming to understand himself as at once modern, scientific, and spiritual, he entered into a publishing network of psychic researchers. He read books by men of intellectual renown including William James and Henri Bergson, who voiced anxieties about credulity while articulating profound hope for the power of telepathy and “mind energy” with worldwide effects. Embedding these psychic narratives within Christian theological commitments, he came to write with considerable confidence, and seemingly little anxiety, about having proved the power of what he called radio mind.

As the other books in this forum show, psychic research and its affiliates, such as mesmerism, magic, and later on, extraterrestrial speculation, exemplify how telling the story of modernity’s resonances requires tracing the paths of colonial resource extraction, slavery, and land dispossession. Indigenous responses to and rejection of such dispossession are also part of the story. I set Du Vernet’s “technophilic” story at this nexus of specifically emplaced and ongoing Nisga’a, Ts’msyen, and Haida land movements in the Pacific Northwest and a traveling network of intellectual and spiritual exploration with varied colonial currents.

As Walker notes, I point repeatedly to the significance of storytelling in terms of the materiality and physicality of different forms of mediation (e.g., dry-plate photography) and the ethics of relationality embedded within these different forms. In doing so, I draw not only from recent discussions of religion and mediation, but also from arguments of Indigenous novelists and scholars about the significance of storytelling as theory, method, and protocol (codes of behavior). Storytelling is always shaped by protocols of address and relationality. Learning this, I also realized that how I would tell The Story of Radio Mind was as much shaped by visiting archives as it was by my experience of telling stories to my children and of talking with Nisga’a and Ojibwe elders and historical experts.

Walker is very right that The Story of Radio Mind does not qualify as an encyclopedic title, since I only dive deeply into the radio mind part of the story in the last two chapters. As I thought about what form the book might take, I decided that I could not consider radio mind until I explained the earlier places and times in Du Vernet’s journey. I also decided that I could not tell the story if I did not venture to those same places and speak to some of the people who live there today. My travels with students and family members to the Rainy River First Nations, the Nisga’a Nation, the Ts’msyen First Nation at Metlakatla, and to Du Vernet’s episcopal seat in Prince Rupert (among other places) became part of the story of radio mind. The Ojibwe, Nisga’a, and Ts’msyen communities I visited had no memories of Frederick Du Vernet, but they did tell stories of other Christian missionaries and of the “Indian Land Movement” in museums, books, and other documents. After bringing Du Vernet’s diary of his visit to the Rainy River in 1898 to the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre, I have since worked with students and community members from the Rainy River First Nations to remediate the diary as an interactive website Kiinawin Kawindomowin Story Nations.

Like Walker, Johnson also points to my persistent focus on the material forms of cosmologies of mediation, characterizing my approach more boldly than I did: “to fuse the spiritual with the material: to place the spirit of matter and matters of spirit at the center of her inquiry.” Similarly, reflecting on radio mind as a metaphor when pondering the fraught concept of reconciliation, she articulates the point of my book in ways that I did not see: “Some ‘frequencies’ are within our range of hearing and we do not have to move in order to receive them. But many others are not, and if we want to make those frequencies audible we will need to shift position, perhaps quite considerably. But how will we know if we are not hearing something? And what motivates us to orient ourselves to a different frequency?” Pointing out the political stakes of what she calls the “conditions of audibility” Johnson gets to the vulnerability of any theoretical—or spiritual—claim: if no one can hear or understand it, it will resonate with no one.

As Johnson makes clear, despite the “facticity” of colonial violence and dispossession and of the persistence of Indigenous refusal of such violence and dispossession, within settler states there are many doubters and deniers of these facts, including many scholars. It is no wonder then, as she points out, that many who do accept that facticity have rejected the concept and project of reconciliation as a “liberal ruse” that tries to “redeem” the settler state by way of a different story.

Framed in the terms of this forum, one of my primary aims in writing this book was to document how Indigenous land movements that countered and, following Audra Simpson, refused colonialism are also among the resonances of modernity. Instead of finding anxieties about credulity or naiveté when reading the stories, ripostes, and petitions of Indigenous people contesting colonialism, however, I found resolute calls to spiritual authority—both Indigenous and Christian—to claim their ground. As Nisga’a Chief Timothy Derrick put it to an Indian Agent in 1908, and as I relay in the book, the chiefs rejected the authority of the Canadian Indian Act and the Indian Agent, along with the very idea of an Indian reserve: “We have come to the conclusion therefore that it is much better for us to try to hold of ourselves the inheritance which God gave our fathers at the beginning.” Indigenous peoples continue to frame their sovereignty as a gift from the Creator, with little care for whether or not such a claim resonated with colonial secular governance. For hundreds of years, Indigenous peoples have been remarkably consistent in referring to their ongoing spiritual jurisdiction in their petitions and legal cases directed at representatives of the Crown in Canada and elsewhere.

Indigenous refusal of colonial sovereignty has long recognized the spiritual vulnerability of colonial settlement. Indigenous leaders such as Derrick regularly clarified to colonial officials that the Crown’s claims to own the land were rooted not in secular law but in Christian doctrines of discovery. They also repeatedly used such doctrines to call to account the Dominion government, whether citing biblical injunctions to not “remove thy neighbour’s landmark” or referencing King George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763.

The spiritual vulnerability of colonial settlement, I would argue, is one important reason why both Christian and secular condemnations of credulity and superstition have long been so anxious, and so resonant, in colonial modernity. As the persistence of Indigenous spiritual jurisdiction shows, however, even if those living in settler-colonial states use concepts such as property, law, and secular reason to close their ears to the steady hum of Indigenous presence on the land, the vibrations refuse to go away. - Pamela E. Klassen

tif.ssrc.org/2019/03/08/networks-of-reception-conditions-of-audibility/#.XIPBBVuprZI.twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.