Jeremy Cooper, Ash before Oak, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2019.

Ash before Oak is a novel in the form of a fictional journal written by a solitary man on a secluded Somerset estate. Ostensibly a nature diary, chronicling the narrator’s interest in the local flora and fauna and the passing of the seasons, Ash before Oak is also the story of a breakdown told slantwise, and of the narrator’s subsequent recovery through his reengagement with the world around him. Written in prose that is as precise as it is beautiful, winner of the 2018 Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize, Jeremy Cooper’s first novel in over a decade is a stunning investigation of the fragility, beauty and strangeness of life.

‘Very moving, beautiful and so thoughtful too – a wonderful evocation of animals and birds, sky and Somerset.’— Kate Mosse

Jeremy Cooper, Kath Trevelyan, Serpent's Tail, 2007.

‘An intriguing and original love story written with an expert eye through the prism of contemporary art.’— Jenny Diski

Kath Trevelyan intends to remain alive until the moment she dies. At seventy-two, she is still a letterpress printer, visiting arts festivals with her daughters and absorbing the richness of the world. Her beloved husband is long dead, and she believes she has had her share of romantic love. Still, her life is filled with beauty: from the splendor of the countryside to the strange innovations of contemporary art. John Garsington feels the same. Though much younger than Kath, he too has a passion for art and work that he loves.

Kath Trevelyan, a 72-year-old widow with 3 grown daughters and 5 grandchildren, "intends to remain alive until the moment she dies." She lives at Parsonage Farm, in the foothills of the Kingsways in Somerset, England, and spends part of each day in her workshop with an ancient Albion printing press—"her joy." After years of "contented widowhood," Kath unexpectedly begins to enjoy the companionship of her neighbor, John Garsington, a retired art dealer 14 years her junior. Over tea or wine they carry on esoteric discussions of British illustrators and engravers and literature they mutually admire; their day trips are embellished with dollops of local British history. Alongside Kath and John's burgeoning relationship, Cooper makes astute observations on the generational interplay between both Kath and her middle daughter, Esther, a frequent visitor, and John and his distressingly pompous and emotionally detached mother. Interjected with thoughts on the meaning of art, the often fragile artistic psyche, and the conundrum of aging, Cooper's engaging third novel challenges the intellect in diverse ways. - Donovan, Deborah

Jeremy Cooper has fashioned quite a lovely book and, perhaps, actress Helen Mirren’s next Oscar-worthy role. Kath Trevelyan, Cooper’s main character, exudes joie de vivre. A vibrant, seventy-two-year-old widow, she remains actively engaged in not only her art (designing and printing unusual, lovingly crafted books) but also communes daily with the bountiful riches of nature found in her rural community, gathering inspiration from her cherished relationships with other artists and neighbors.

A close neighbor, John Garsington, whom Cooper paints with much more subtle strokes, is 14 years younger than Kath but shares her passion for modern art, beautiful handcrafted furniture, and living an unhurried, contemplative life in the English countryside. Although many of the references to architecture, music and art are firmly lodged in recent history, the way Kath and John both live hails back to a slower, more aesthetically pleasing era.

One of the reasons it is easy to picture a film treatment of this story is Cooper’s flowing, visually clear language. Written in a stream-of-consciousness style, Kath’s meanderings from her studio, equipped with its antique Albion press into the verdant local countryside -- first for a reflective picnic then pausing to swim undiscovered in a hidden grotto -- reads as naturally as if we experienced the day ourselves. Another outing captures Cothay Manor:

I found it quite realistic that this December–May romance would blossom without pages of angst over the age difference. Kath accepts life as it comes and admirably opens herself to this unexpected gift of physical affection and mutual dependence once again so many years later in her life. In a rare passage reflecting on their relationship, Kath admits, “I love being here, with you. I’m afraid it’s taken the last drop of my courage to let it happen. I can’t be alone again....” John had obviously worked through any reservations he had during the mysterious break early on in their friendship.

Esther, Kath’s troubled middle daughter, is the most frequent visitor to Kath and John’s idyll. Cooper provides a fine twist to the story by allowing us to learn more about the next generation through Esther: her difficult past, current physical ills, and her hopes for an unexpected happy ending. Through Esther, readers also discover other dimensions of Kath: her married life, her role as a mother, and the obstacles that she has overcome to remain content. It is slightly odd that Kath’s other two daughters and her grandchildren play such a small role in the book, although this is clearly proof of their distant relationships.

Ultimately Cooper’s well-written work rests on the extreme likability of its main character. Readers not only wish for the best for Kath, they want to live out their senior years similarly engaged in their passions: they want to basically become Kath. The perfect metaphor for Kath and John’s entire existence is quoted in Cooper’s work where he describes a book Kath pressed for a dear friend called Other Men’s Flowers. “The title was not his…a quote from Montaigne: ‘I have gathered a posie of other men’s flowers and nothing but the thread that binds them is my own.’ ” Kath and John have indeed found that a common love of craftsmanship as well as dedication to the art of producing unique and beautiful works, is more than enough.

http://www.curledup.com/kath_trevelyan.htm

The appearance of a long quote from W.G. Sebald’s Campo Santo gave me the excuse to read Jeremy Cooper’s new novel Kath Trevelyan (London: Serpent’s Tail 2007). Cooper, an art historian who has worked for Sotheby’s and now, according to his brief book bio, owns a gallery in Bloomsbury, has created a portrait of seventy-something Kath Trevelyan and, to a lesser extent, her rural neighbor and friend John. Kath is a letterpress printer who draws, makes prints, and produces small edition fine press books.For reasons that are often obscure to her and to this reader, Kath is drawn to John, a fifty-something retired London gallerist who is moody and inarticulate about personal relationships. Kath’s daughter Esther also makes frequent appearances, effectively giving Kath a real person to talk to now and then.

The handful of characters that populate Kath Trevelyan lead unhurried, contemplative lives in rural England, with periodic travels around the countryside and into London. They seem to devote a considerable portion of their day observing and appreciating their natural surroundings. In addition, Kath and John live amidst a veritable Antiques Roadshow of objects: treasured collectibles, beautiful books, memory-laden memorabilia, works of art, hand-crafted furniture. Now and then Cooper’s background results in passages that read as if they were snipped from an auction catalog or a museum wall label, but most of the time his descriptive passages are engaging, recalling that other one-time employee of Sotheby’s – Bruce Chatwin. Did I mention that Kath hasn’t owned a television set since her last child moved out, which, by my calculations, is the 1950s?All of this tends to give Kath Trevelyan the aura of a Merchant/Ivory production of an E.M. Forster novel.

The principal plot line is the budding romance between Kath and John, two largely mis-matched people who just may or may not have something to offer the other. After more than 275 pages of Will it happen? and Could it possibly work?, Kath and John are suddenly, without warning or fanfare, in bed. Did we miss something? Apparently so. Oh those Brits, one is tempted to mutter.

Fortunately, Cooper is after something more than nostalgia. By temperament, John has been a devoted follower of the very latest on the London art scene for decades. As a gallery owner he started with artists Gilbert & George, Richard Hamilton, and Hamish Fulton, then kept up with the changing times and he now follows a trend that is decidedly cutting edge. His current passion is Gavin Turk, one of the notorious Young British Artists originally collected and made famous by Charles Saatchi. John has just written a short essay about Turk. This provides Kath with a solution to her late-life crisis. Kath, it seems, has begun to feel that her current project, an expensive limited edition book on the theme of trees, replete with metaphors for longevity and strength, is too conservative. She craves something more “experimental” and, as a cure, proposes to create a kind of anti-book using John’s essay on Gavin Turk. Within the tradition-bound world of collectible fine press editions, this project, which she will finally title Notabook probably does strike an avant guard note, but it doesn’t seem to bridge the huge gap between her world and that of Gavin Turk.

Much of the novel is delightfully observational, rounding out the portraits of Kath, John, and, to a lesser extent, Esther. Cooper is a very visual writer, a skill matched by his difficulty with conversation. Nearly everything that his characters speak comes out a little stilted. Here’s John in a crucial scene, calling on the phone early in the novel to break it all off with Kath:

I mustn’t forget about Sebald, whose writing makes a guest appearance on pages 156-158. As part of the research for her book about trees, Kath reads Campo Santo and quotes a lengthy segment about the forests of Corsica from the prose piece The Alps in the Sea. Curiously, as Kath plots out the text and images that will go in her book, she herself sounds distinctly Sebaldian:

https://sebald.wordpress.com/category/jeremy-cooper/

Jeremy Cooper, Women Beware, 2006.

Women Beware is a raunchy romp about the careless choices, desperate relationships, selfishness and redemption of a young man in must. The story is driven by lust, depravity, infidelity, fear, guilt, cowardice, love, money, rape, murder and lies.

The hero stumbles upon the seductive power of the smell of a tarry by-product stream from the chemical plant he is working on. It drips onto his shoe with startling results. What an opportunity! How can it all go wrong?

Kath Trevelyan, a 72-year-old widow with 3 grown daughters and 5 grandchildren, "intends to remain alive until the moment she dies." She lives at Parsonage Farm, in the foothills of the Kingsways in Somerset, England, and spends part of each day in her workshop with an ancient Albion printing press—"her joy." After years of "contented widowhood," Kath unexpectedly begins to enjoy the companionship of her neighbor, John Garsington, a retired art dealer 14 years her junior. Over tea or wine they carry on esoteric discussions of British illustrators and engravers and literature they mutually admire; their day trips are embellished with dollops of local British history. Alongside Kath and John's burgeoning relationship, Cooper makes astute observations on the generational interplay between both Kath and her middle daughter, Esther, a frequent visitor, and John and his distressingly pompous and emotionally detached mother. Interjected with thoughts on the meaning of art, the often fragile artistic psyche, and the conundrum of aging, Cooper's engaging third novel challenges the intellect in diverse ways. - Donovan, Deborah

Jeremy Cooper has fashioned quite a lovely book and, perhaps, actress Helen Mirren’s next Oscar-worthy role. Kath Trevelyan, Cooper’s main character, exudes joie de vivre. A vibrant, seventy-two-year-old widow, she remains actively engaged in not only her art (designing and printing unusual, lovingly crafted books) but also communes daily with the bountiful riches of nature found in her rural community, gathering inspiration from her cherished relationships with other artists and neighbors.

A close neighbor, John Garsington, whom Cooper paints with much more subtle strokes, is 14 years younger than Kath but shares her passion for modern art, beautiful handcrafted furniture, and living an unhurried, contemplative life in the English countryside. Although many of the references to architecture, music and art are firmly lodged in recent history, the way Kath and John both live hails back to a slower, more aesthetically pleasing era.

One of the reasons it is easy to picture a film treatment of this story is Cooper’s flowing, visually clear language. Written in a stream-of-consciousness style, Kath’s meanderings from her studio, equipped with its antique Albion press into the verdant local countryside -- first for a reflective picnic then pausing to swim undiscovered in a hidden grotto -- reads as naturally as if we experienced the day ourselves. Another outing captures Cothay Manor:

“Seasonal visitors enter through the meadow and begin with the relative wildness of the riverbank and bog garden, before arrival at the head of a clipped yew walk, long and tall, where Kath stops to sit on a stone bench in the shade. The creative intensity and strength of character at Cothay is palpable. She lets Yoko and Don wander on alone, hand-in-hand through gardens built in a progression of secluded rooms and corridors, difference and cohesion the living genius of the place.”Occasionally John’s comments come off as stilted but do serve to reinforce the reader’s developing mental image of him as somewhat awkward, particularly in his handling of intimate relationships.

“He stops. Pulls with his fingers at his lips, the furrow on the bridge of his nose deepening to the blackness of a stagnant ditch.”When the neighborly relations between Kath and John seem to develop into something more than friendship, it is by infinitely slow degrees - even totally halted at one point, then refueled by compatible discussions, enjoyable artistic rendezvous, energetic travels, social forays, and, finally, a conscious collaboration on an important Parsonage Press project. The reader gets sudden confirmation of the physical attachment quite a ways into the novel; Cooper avoided giving this aspect of the relationship undue attention, instead using the physical to only reinforce the reader’s sense of Kath and John’s fully developed mental and spiritual closeness.

I found it quite realistic that this December–May romance would blossom without pages of angst over the age difference. Kath accepts life as it comes and admirably opens herself to this unexpected gift of physical affection and mutual dependence once again so many years later in her life. In a rare passage reflecting on their relationship, Kath admits, “I love being here, with you. I’m afraid it’s taken the last drop of my courage to let it happen. I can’t be alone again....” John had obviously worked through any reservations he had during the mysterious break early on in their friendship.

Esther, Kath’s troubled middle daughter, is the most frequent visitor to Kath and John’s idyll. Cooper provides a fine twist to the story by allowing us to learn more about the next generation through Esther: her difficult past, current physical ills, and her hopes for an unexpected happy ending. Through Esther, readers also discover other dimensions of Kath: her married life, her role as a mother, and the obstacles that she has overcome to remain content. It is slightly odd that Kath’s other two daughters and her grandchildren play such a small role in the book, although this is clearly proof of their distant relationships.

Ultimately Cooper’s well-written work rests on the extreme likability of its main character. Readers not only wish for the best for Kath, they want to live out their senior years similarly engaged in their passions: they want to basically become Kath. The perfect metaphor for Kath and John’s entire existence is quoted in Cooper’s work where he describes a book Kath pressed for a dear friend called Other Men’s Flowers. “The title was not his…a quote from Montaigne: ‘I have gathered a posie of other men’s flowers and nothing but the thread that binds them is my own.’ ” Kath and John have indeed found that a common love of craftsmanship as well as dedication to the art of producing unique and beautiful works, is more than enough.

“It isn’t easy to describe the spirit with which Kath embarks on the working days in her studio. Habit and familiarity are important – less pedestrian qualities than might be assumed, for they breed a sense of belonging, help the beat of her blood slow, guide the rhythms of the mind into unfettered channels of experience. Kath’s work, although ostensibly by others, is in fact of and from her private self. That’s why it matters.Readers will enjoy Cooper’s writing even more if they have a familiarity with English slang, the geography of Somerset, England, important names and works of the contemporary British art scene, and cursory knowledge of antique printing machinery and tomes. Cooper, a trained art historian, worked for Sotheby’s and as a private art consultant before opening his own gallery in Bloomsbury. He is the author of a number of books on art and antiques and has appeared on the popular television program Antiques Roadshow. He has also written for the Sunday Times, Observer and Sunday Telegraph. His other novels - Ruth, Us and The Folded Lie - also received favorable reviews. - Leslie Raith

“There is physicality about the making of any art. Nothing ever is only an idea: it is based on something that has happened, and happens again in another guise as the piece finds its form. The realisation of a concept, a mental construct, is also physical, even when there’s nothing to show on completion of the work.”

http://www.curledup.com/kath_trevelyan.htm

The appearance of a long quote from W.G. Sebald’s Campo Santo gave me the excuse to read Jeremy Cooper’s new novel Kath Trevelyan (London: Serpent’s Tail 2007). Cooper, an art historian who has worked for Sotheby’s and now, according to his brief book bio, owns a gallery in Bloomsbury, has created a portrait of seventy-something Kath Trevelyan and, to a lesser extent, her rural neighbor and friend John. Kath is a letterpress printer who draws, makes prints, and produces small edition fine press books.For reasons that are often obscure to her and to this reader, Kath is drawn to John, a fifty-something retired London gallerist who is moody and inarticulate about personal relationships. Kath’s daughter Esther also makes frequent appearances, effectively giving Kath a real person to talk to now and then.

The handful of characters that populate Kath Trevelyan lead unhurried, contemplative lives in rural England, with periodic travels around the countryside and into London. They seem to devote a considerable portion of their day observing and appreciating their natural surroundings. In addition, Kath and John live amidst a veritable Antiques Roadshow of objects: treasured collectibles, beautiful books, memory-laden memorabilia, works of art, hand-crafted furniture. Now and then Cooper’s background results in passages that read as if they were snipped from an auction catalog or a museum wall label, but most of the time his descriptive passages are engaging, recalling that other one-time employee of Sotheby’s – Bruce Chatwin. Did I mention that Kath hasn’t owned a television set since her last child moved out, which, by my calculations, is the 1950s?All of this tends to give Kath Trevelyan the aura of a Merchant/Ivory production of an E.M. Forster novel.

The principal plot line is the budding romance between Kath and John, two largely mis-matched people who just may or may not have something to offer the other. After more than 275 pages of Will it happen? and Could it possibly work?, Kath and John are suddenly, without warning or fanfare, in bed. Did we miss something? Apparently so. Oh those Brits, one is tempted to mutter.

Fortunately, Cooper is after something more than nostalgia. By temperament, John has been a devoted follower of the very latest on the London art scene for decades. As a gallery owner he started with artists Gilbert & George, Richard Hamilton, and Hamish Fulton, then kept up with the changing times and he now follows a trend that is decidedly cutting edge. His current passion is Gavin Turk, one of the notorious Young British Artists originally collected and made famous by Charles Saatchi. John has just written a short essay about Turk. This provides Kath with a solution to her late-life crisis. Kath, it seems, has begun to feel that her current project, an expensive limited edition book on the theme of trees, replete with metaphors for longevity and strength, is too conservative. She craves something more “experimental” and, as a cure, proposes to create a kind of anti-book using John’s essay on Gavin Turk. Within the tradition-bound world of collectible fine press editions, this project, which she will finally title Notabook probably does strike an avant guard note, but it doesn’t seem to bridge the huge gap between her world and that of Gavin Turk.

Much of the novel is delightfully observational, rounding out the portraits of Kath, John, and, to a lesser extent, Esther. Cooper is a very visual writer, a skill matched by his difficulty with conversation. Nearly everything that his characters speak comes out a little stilted. Here’s John in a crucial scene, calling on the phone early in the novel to break it all off with Kath:

I’m stopping our contact. We’re too different. It’s for the best. We’ll both be able to get on with things now. You’ve got your book, with William. And I’m writing this article. About the performance art of Gavin Turk. You”ll get over it. Don’t worry. It was a mistake. We can never be proper friends.The real pleasure of Kath Trevelyan, it seems to me, is being airlifted into a territory where every conversation is literate, where every object is beautiful, and everyone lives at the highest level of alertness to the world around them. Gavin Turk nowithstanding, it’s still Merchant/Ivory-land, but it’s a very pleasant way to spend a few hours.

I mustn’t forget about Sebald, whose writing makes a guest appearance on pages 156-158. As part of the research for her book about trees, Kath reads Campo Santo and quotes a lengthy segment about the forests of Corsica from the prose piece The Alps in the Sea. Curiously, as Kath plots out the text and images that will go in her book, she herself sounds distinctly Sebaldian:

…text and image shouldn’t explain, let alone illustrate each other. Maybe enter into a sort of dialogue, reverberating back and forth. (page. 129)The first edition of Kath Trevelyan is a compact 5 by 7 inch paperback with a cover image by artist Peter Doig, an enigmatic etching called White Out, 1996, which depicts one of his awkwardly formal figures standing in front of a ragged line of trees in winter. - Terry Pitts

https://sebald.wordpress.com/category/jeremy-cooper/

Jeremy Cooper, Women Beware, 2006.

Women Beware is a raunchy romp about the careless choices, desperate relationships, selfishness and redemption of a young man in must. The story is driven by lust, depravity, infidelity, fear, guilt, cowardice, love, money, rape, murder and lies.

The hero stumbles upon the seductive power of the smell of a tarry by-product stream from the chemical plant he is working on. It drips onto his shoe with startling results. What an opportunity! How can it all go wrong?

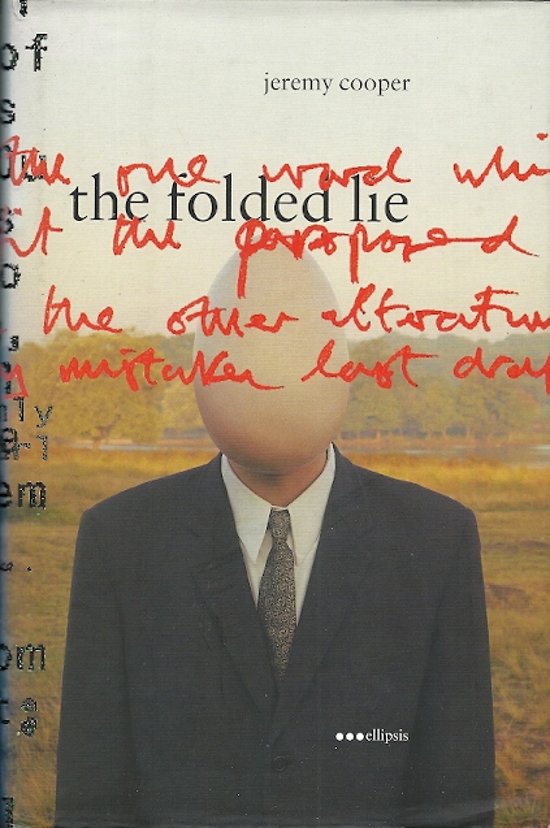

Jeremy Cooper, The Folded Lie, Ellipsis, 1998.

‘Quite unlike any other novel published this year: a bold, radical, almost embarrassingly direct assault on modern complacencies, both political and artistic.’— Jonathan Coe

‘Complex, thought-provoking and pertinent... A clever, partial book, written in a fluent, comfortable narrative style.’— Financial Times

‘What a really admirable novel. I read The Folded Lie with great pleasure.’— Fay Weldon

‘The Folded Lie is a timely and perceptive new novel.’— Tony Benn

Jeremy Cooper, The World Exists to Be Put on a Postcard: Artists' postcards from 1960 to now, Thames & Hudson, 2019.

The postcard as you’ve never seen it before. This appealing book collects the best of these mail-able, miniature works of art by the likes of Yoko Ono and Carl Andre.

The accessibility and familiarity of a postcard makes it an artistic medium rich with potential for subversion, appropriation, or manipulation for political, satirical, revolutionary, or playful intent. The inexpensiveness of production encourages artists to experiment with their design; the only artistic restriction: that it fits through the mailbox slot. Unlike traditional works of art, the postcard requires nothing more than a stamp for it to be seen on the other side of the world. Made of commonplace material, postcards invite handling, asking to be picked up, turned over, and shown to friends―to be included in our lives.

The World Exists to Be Put on a Postcard features postcards, several reproduced at actual size, designed by notable modern and contemporary artists, including Carl Andre, Eleanor Antin, Joseph Beuys, Tacita Dean, Gilbert & George, Richard Hamilton, Susan Hiller, Richard Long, Bruce Nauman, Yoko Ono, Dieter Roth, Gavin Turk, Mark Wallinger, Rachel Whiteread, and Hannah Wilke, many of which are published here for the first time. Organized thematically into chapters, such as “Graphic Postcards,” “Political Postcards,” “Portrait Postcards,” and “Composite Postcards,” this book demonstrates the significance of artists’ postcards in contemporary art.

Jeremy Cooper, Victorian and Edwardian Decor: From the Gothic Revival to Art Nouveau, Abbeville Press, 1987.

Jeremy Cooper has recently given to the British Museum an important collection of artists’ postcards; his book on the subject, The World Exists to be Put on a Postcard, is published by Thames & Hudson. He appeared in the first twenty-four episodes of the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow, was co-presenter in the early 1980s of Radio 4’s The Week’s Antiques, and is the author of four novels and a number of works of non-fiction on art and design.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.