Gerald Murnane, A Million Windows, Giramondo, 2014.

read it at Google Books

A

publisher many years ago said that Gerald Murnane was a Proust who had

never left Combray. Both parts of this statement remain true some 30

years after Murnane started publishing; he is a writer of the first

rank, a writer that critics such as Frank Kermode and Northrop Frye,

the most eminent of people around, were dazzled by at a glimpse, and yet

any given work by him has a greater resemblance to any other such work

than is usual in a writer of such marked distinction.

Murnane

is constantly revisiting, with endless variegations and minute tonal

shifts and dislocations and re-emergences of patterning, the apparent

tiny variations of his obsessive compass: woman, landscape, grasslands.

It

is as if the mind knew no other music than the topography of its own

backyard, as if it could only articulate through particular words, all

but lost to collective memory unless those memories abide in the endless

canonical hours of Murnane's monk-like fiction, the ambient light and

the endless declensions of the soul's yearning.

And yet no living Australian writer, not even Les Murray, has higher claims to permanence or a richer sense of distinction.

Visual artists such as Bill Henson flock to Murnane, I suspect because

they recognise the relentless abstractionism and the explicit

preoccupation with form – Murnane's is a fiction forever talking about

writing fiction – as an absolutely humble homage to the grandeur of art

and the extraordinary difficulty, as well as the radiance, that comes

from trying.

The

art critic Norbert Loeffler said once, of Peter Booth's painting:

‘‘Look at what this man can do with his pygmy vocabulary!’’ And Murnane

– a little like the great American poet Wallace Stevens – is intent on

the thousand shades of linguistic protection with which someone might

look at the fire that comes out of the sun and then look into the heart

of it.

That

last phrase echoes a poem not by Stevens but by Peter Porter, an

opposite writer to Murnane with his easy talkiness and his endless

extroverted erudition but one with a comparable formal intensity and

desperation of purpose.

Some of the greatest Porter poems come out

of his wife dying tragically. The death of Murnane's wife, Catherine, a

few years ago after a long illness has led to the fiction maker's shift

from Macleod in Melbourne's outer suburbs to the town of Goroke in the

Wimmera.

His new book, A Million Windows, is nothing if not like his old ones. Gerald Murnane begins with Tamarisk Row

in 1974 with a book of small-town life that is at the same time haunted

and then dwarfed by a young boy's preoccupation with colours and icons

and racehorses. His second, A Lifetime on Clouds, is a nearly

comic novel, full of great gulfs of unstable poignancy, about an

imaginary woman, a wet dream, hilarious and hysterical, but with a sense

(barely admitted) of the tears in things. It is in 1982 with The Plains

that Murnane seems to meet his destiny by discovering – the way someone

might discover a desolation or a delusion – the way he can make art out

of the preoccupation with art.

For

Murnane it's all a matter of ‘‘true fiction’’, an enigmatic phrase

analogous to something such as ‘‘authentic poetry’’ or perhaps to what

Pound meant when he said, ‘‘The sincerity is in the technique’’.

If you want the supreme triumph of Murnane's method read Inland

(1988), which he has admitted is the God-given book, a work that

dazzles the mind with its grandeur and touches the heart with a great

wave of feeling and brings to the point of maximum reality the grave and

soulful preoccupations that run through every bit of fiction Murnane

has ever written.

In A Million Windows

these preoccupations are presented and represented with great poise and

power in a way that might easily seem schematic, but nothing is ever

quite what it seems in this writer's fiction.

We

hear of a house of fiction in which a great catalogue and cavalcade of

writers (analogous to the various characters inhabiting a film by a

famous filmmaker, recapitulating his previous personae) take up shelter

and yabber or are reported as yabbering about the nature of fiction. We

learn of a writer who died drunk in a country town and who sounds like

the great gorgeous dandy of language and abuse, Hal Porter, and the fact

that he (if he is the nameless source) said that in his childhood the

view from his balcony – that sounds like the cast-iron one in Bellair

Street, Kensington, immortalised in memoir – showed the sun-touched

windows of a million houses like so many gleaming golden drops of oil.

That's

one recurring item for meditation or occasion for epiphany, honoured or

delayed, in what is in a sustained dithyrambic way, a long (fictional)

meditation on the nature of fiction in something like the way T.S.

Eliot's Four Quartets could be said to be a meditation on the nature of poetry.

In practice, with A Million Windows,

Murnane is playing something like the same trick Eliot did in his suite

of poems. He is enunciating truths about fiction that partake of the

paradox of the Cretan liar, because this book, forever talking about

books – and attempting to tell ‘‘the truth’’ about them – is moving with

its own sense of mystery and undisclosed purpose through a wilderness

of symbols of which its elements – its invocation of Henry James, say,

as a hero of fiction, always the protagonist of his own sentences – both

is and isn't a sleight of hand.

In the long distance of A Million Windows,

there is a lonesome, shy, inarticulate male child (to call him a boy

would be too temporally limiting) pining for dark-haired women, feeling

serenity only at the prospect of flat land and grass, believing with the

fullest possible sense of vocation – the religious one that sends

people to seminaries and makes them believe in eternity and therefore

the nullity of time – in the power of words, arranged according to the

truth of faith, into a pattern, where rhythm and beauty and truth are

one.

Is

it a fiction? It is, Murnane seems to whisper, the necessary fiction on

which the world of the imagination, which is the only world we have, is

built.

Such

is the world we have. Such is the world to come. Buy this book and read

it like a bible. Never mind your fury, never mind your boredom. - Peter Craven

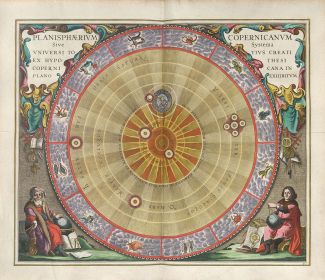

Gerald Murnane’s A Million Windows takes both its title and epigraph from the preface of the 1908 New York edition of The Portrait of a Lady, in which Henry James states:

The

house of fiction has in short not one window, but a million – a number

of possible windows not to be reckoned, rather; every one of which has

been pierced, or is still pierceable, in its vast front, by the need of

the individual vision and by the pressure of the individual will.

Murnane’s

novel materially appropriates James’s concept: the narrator resides

with many other authors in one wing of an enormous mansion that he

refers to as the ‘House of Fiction’, where they write, share stories,

reflect on the practice of writing, and take part in elaborate rituals

based on James’s own fiction. But in rendering the figurative House of

Fiction as a literal setting, the novel obscures its own fraught

relationship to James’s metaphor, which A Million Windows revises in subtle but important ways.

James

employs his ‘House of Fiction’ metaphor to illustrate the complicated

relationship between a novel’s subject matter, its literary form, and

the psychological temperament of its author. What the author glimpses

through the windows of the house of fiction comprises the novel’s

subject, while the shape of the window itself – ‘the pierced aperture,

either broad or balconied or slit-like and low-browed’ – is its

‘literary form’. But in arguing that form and content are ‘as nothing

without the posted presence of the watcher’, James elevates the

disposition of the author over any particular quality of the text. The

work of fiction is defined by the writer’s individual consciousness:

‘Tell me what the artist is,’ James asserts, ‘and I will tell you of

what he has been conscious.’ It is precisely this direct connection

between authorial consciousness and fiction that A Million Windows scrutinises.

A Million Windows

might appear to enact James’s metaphor. Lacking a discrete subject or

plot, the novel’s various narratives, digressions and remembrances

cohere through the singular voice of the narrator, who gives shape and

form to these fragments of lived experience and readerly reflection. In

the novel’s slow agglomeration of meaning, which coalesces around

unexpected resonances between events, memories and allusions, A Million Windows’

organising principle – if, indeed, it has one – would appear to be

located within the individual consciousness and experience of its

author. Readers are given access to private details of the author’s

life, which generates both intimacy and claustrophobia. Much of A Million Windows,

like Murnane’s other fiction, operates in a seemingly confessional

mode: the narrator at various points describes his problems with

drinking, aspects of his troubled upbringing, several instances of ‘what

was mostly called in those years a nervous breakdown’, two encounters

that appear to have been extramarital affairs, and many other deeply

personal and often traumatic experiences.

But A Million Windows’ first sentence undermines the relationship between author, form and content in James’s metaphor:

The

single holland blind in his room was still drawn down in late

afternoon, although he would have got out of his bed and would have

washed and dressed at first light.

This innocuous

holland blind is a barrier that, like Murnane’s House of Fiction itself,

is both figurative and literal. For James, the work of art cannot be

separated from the consciousness of the author (even if it is mediated

by literary form and subject matter); for Murnane, the author is always

remote and inaccessible, and the work of fiction is a veil, rather than a

prismatic sublimation of the writerly ego. Any trace of authorial

consciousness – or the ‘breathing author’, to use Murnane’s term – is no

more than the attenuated glow of sunlight at the edges of a drawn

curtain.

The appearance of this seemingly incidental holland blind

signals that Murnane has appropriated James’s metaphor as his own.

Indeed, large manor houses have been a recurrent trope throughout

Murnane’s fiction, figuring prominently in almost all of his books.

Murnane has even previously employed the conceit of a large manor house

filled with writers in his short story ‘Stone Quarry’ from Velvet Waters

(1990), which imagines the goings-on at a writers’ retreat called Waldo

(a punning allusion both to the famous artists’ retreat Yaddo and to

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s notion of self-reliance) where the writers are not

allowed to speak or communicate with each other in any way. In this

sense, Murnane’s appropriation of James’s House of Fiction is also a

form of self-quotation. Such self-reference becomes an essential part of

A Million Windows, since much of the novel constitutes more or less explicit revisions of episodes from Murnane’s earlier works.

Here Murnane’s procedure recalls Giorgio Agamben’s suggestion (which, appropriately, quotes Walter Benjamin) that the

particular

power of quotations arises . . . not from their ability to transmit

that past and allow the reader to relive it but, on the contrary, from

their capacity to ‘make a clean sweep, to expel from the context, to

destroy’.

A Million Windows always

appropriates its source texts to new ends, and the novel’s use of

quotation is frequently violent and coercive, rather than a simple

matter of reference.

This is important because A Million Windows

is a novel that is cobbled together from various references and

quotations, but its allusions always move in at least two directions at

once. They send the reader outside the text to works by other authors,

while also recalling Murnane’s own body of work. A Million Windows’

opening section, for example, goes on to describe the author behind the

holland blind writing down a ‘remembered version of a quotation’

written by a ‘male person from an earlier century’ whose name he ‘cannot

recall’, which reads: ‘All our troubles arise from our being unwilling

to keep to our room.’

While the quotation refers to an unnamed

outside source, it also recalls the various references to solitary

writers, usually seated near or close to windows, throughout Murnane’s

writing. In Landscape with Landscape (1985), for example, the

narrator imagines the nineteenth century Italian writer Giacomo Leopardi

‘imprisoned in his parents house’ and ‘sitting at his desk in deep

shadow but in sight of a distant rectangle of white sunlight that was

all he saw all day of some far-ranging view of Italian hills’. In Velvet Waters,

Murnane even provides a catalogue of ‘writers whose way of life was

more or less solitary’, including ‘Kafka, Emily Dickinson, Giacomo

Leopardi, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Michel de Ghelderode, A. E. Housman,

Thomas Merton, Gerald Basil Edwards, C. W. Killeaton’. The last author

is the protagonist of Murnane’s first published novel, Tamarisk Row (1974).

External

reference is also internal reference, which operates within a network

of accumulated meaning across Murnane’s fiction that is arguably more

significant than the provenance of the quotation. Whatever its origin,

the quotation – implicitly associated with Murnane’s pantheon of

solitary writers – seems to recall Proust in his cork-lined room, or

Kafka’s famous dictum that

You do not need to leave

your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen,

simply wait, be quiet, still and solitary. The world will freely offer

itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy

at your feet.

And yet the actual quotation is a gloss

on Blaise Pascal’s statement, written hundreds of years before any of

those solitary writers were alive: ‘All of humanity’s problems stem from

man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.’ It is through the

omission of its author that the quotation may be placed it in an

entirely different context, thereby altering its significance.

A Million Windows

obsessively returns to questions about the relationship between fiction

and the world, between subject matter and literary form, and between

readers and authors. It reflects on these matters at greater length than

Murnane’s previous works, but they are hardly new considerations in his

writing. In fact, this novel revises ideas first articulated in the

‘essay’ (Murnane has noted that there is no substantive difference

between those works he has called either essays or fiction) from Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs

(2005) entitled ‘The Breathing Author’. In both texts, Murnane argues

for a concept of authorship that is deeply indebted to the literary

critic and rhetorician Wayne C. Booth, who argued that the actual human

who produces literary works is ‘immeasurably complex and largely

unknown, even to those who are most intimate’.

Booth’s The Rhetoric of Fiction

(1961; revised 1983) is the unnamed book ‘almost wholly given over to a

study of point-of-view in fiction’ written by ‘a professor in an

American university’ that the narrator of A Million Windows

claims to have read closely in the first edition and then read again

‘nearly ten years later’ in ‘the revised and expanded second edition’.

For those keeping score, the other unnamed scholarly work of

‘narratology’ – which the narrator finds confusing, despite its

inclusion of ‘several charts or diagrams’ that illustrate ‘the many

possible kinds of fictional narration’ – is Franz K. Stanzel’s A Theory of Narrative

(1984). Murnane, following Booth, contrasts the ‘breathing author’ with

what is called the ‘implied author’ – a concept Murnane has employed in

his fiction for several decades now to describe his narrators, who

resemble, but are nonetheless ontologically and narratologically

distinct from the flesh-and-blood-author called Gerald Murnane.

Much of Murnane’s fiction, at least since Landscape with Landscape

(1985), has examined this gap, or fissure, between the breathing author

and the implied author, creatively exploiting their non-identical

similitude. This focus on authorship is accompanied by extensive

reflection on the cognitive process of reading itself, most notably in

Murnane’s previous work, A History of Books (2012). In

considering such issues, Murnane’s fiction over the last thirty years

has examined how textual meaning (if that is the right word, since the

narrator of A Million Windows states that ‘What others might have called meaning he called connectedness’) is transferred from the breathing author into the fictional text by the implied author and then, ideally, into the minds of those that Murnane terms ‘discerning readers’.

His

point is not to delineate a phenomenology of reading, but rather to

demonstrate the almost infinite complexity of an undertaking that is

rarely viewed critically. As Murnane says repeatedly across his works,

he has no theory of the mind and remains deeply suspicious of systematic

accounts of cognition, whether philosophical or psychological. Instead,

his oblique examination of reading recalls Viktor Shklovsky’s notion of

‘estrangement’: it seeks to demonstrate the complexity and the oddity

of a reading process that is more or less taken for granted.

Murnane

is thus a writer whose subject matter is writing and reading, but his

interests are altogether different from the various postmodern

practitioners of metafiction – such as John Barth, John Fowles, Italo

Calvino, B. S. Johnson and Robert Coover, – to whom he has frequently

been compared. The narrator of A Million Windows explicitly

denies any connection with such writing, saying ‘I can recall today no

instance of my admiring some or another work of self-referential

fiction, much less of my trying to write such a work.’ He goes on

describe feeling ‘repelled’ by the ‘more extreme examples’ of this

writing, in which narrators would ‘pause in their reporting’ as if

‘unable to decide which of several possible courses of events should

follow from that point’. The narrator argues that authors of such novels

incorrectly presume fictional characters are ‘of the same order’ as

real people who ‘live out their lives’ and can be observed ‘in the way

that the makers of film observe their characters’. The narrator instead

argues that the fictional world that characters inhabit is ‘somewhere

vast and vague’ that is ‘nowhere to be seen’ and thus is entirely unlike

‘the visible world’ in which readers and authors exist. For Murnane,

metafiction fails because it equates two entities – the fictional and

the actual – that are incomparable. ‘Any writer claiming otherwise,’ the

narrator states, could never ‘be anything but a fool’.

This

critique of self-referential fiction illustrates that Murnane’s own use

of self-reflexivity is motivated, not by escapist aestheticism, but by

more practical concerns. As the narrator of A Million Windows

argues, one of the chief concerns of his writing is to ‘prevent’ readers

from ‘apprehending my subject-matter in the way that a viewer . . .

apprehends the subject-matter of a film’, such that fiction and reality

would appear to be equated. Murnane highlights the otherness of fiction,

employing what he calls ‘considered narration’ – a technique that

requires a ‘strong narrator’ who, instead of hiding ‘behind his or her

subject matter as the author of a filmscript’, openly selects and

interprets the subject-matter of the fictional work itself. Murnane does

not want to create fiction that simply simulates a possible (but

non-existent) reality; rather, he desires to produce a work of ‘true

fiction’ that reports ‘what no one but the narrator has seen or heard in

the invisible setting where all fiction takes place’.

As the narrator of A Million Windows

repeatedly reaffirms, the most important compositional principle in

Murnane’s work is a genuine and thoroughgoing respect for the space of

fiction as something radically different from everyday reality. It is

this conviction, for example, that motivates the narrator’s critical

dismissal of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) – although the book is, of course, never referred to by name – on the grounds that

each

of the monologues, as I call them, was made up of the same unrelenting

prose. Authors of fiction purporting to come from a medley of voices are

seldom skillful enough to compose a distinctive prose for each supposed

speaker.

Metafictional authors fail because they

presume that fictional characters are like real people; Marquez’s work

fails because it does not give adequate specificity and agency to the

various voices occupying the novel, which is thereby reduced to a simple

reflection of the authorial ego. Both approaches, according to

Murnane’s narrator, do not sufficiently respect the alterity of the

space of fiction.

On similar grounds, the narrator entirely

rejects the use of dialogue as a ‘trick’ that writers of fiction should

never employ. The narrator’s prohibition stems from the belief that

‘dialogue . . . readily persuades the undiscerning reader that the

purpose of fiction is to provide the nearest possible equivalents of

experiences obtainable in this, the visible world where books are

written and read’. Dialogue threatens to flatten out the space of

literature by making it conform to the rules of everyday reality, so it

must be scrupulously avoided.

A Million Windows is a work

of fiction, but it is also an aesthetic manifesto and a reflection on

Murnane’s artistic method. And this explication of the rationale behind

Murnane’s aesthetic choices necessarily affects the way that we

understand his fiction. What A Million Windows clarifies is not

simply that there is a method to Murnane’s madness, but rather that

Murnane’s unswerving devotion to a series of compositional principles is

responsible for the unique texture of his work. His fiction – while it

may lack more traditional plot structures – is a product of an alternate

but rigorous set of procedures, rather than simply being ‘experimental’

or speculative in a banal sense. The narrator indirectly asserts this

by referring (with no small irony) to the novel’s original ‘plan’ in

explicit detail:

When I first drew up the plan for this work of

fiction, I intended this, the nineteenth of thirty-four sections, to

comprise an argument in favour of reliable narrators as against

unreliable narrators or absent narrators.

Murnane has implicitly

affirmed the systematic nature of his writing elsewhere, such as when

the narrator of ‘The Breathing Author’ says:

I have

been described by my wife and by several friends as the most organized

person they have ever known, and I admit to a love of order and of

devising systems for storing and retrieving things.

Despite appearances, A Million Windows,

like Murnane’s other novels, reflects this love of both system and

archive, which manifests as a larger desire for a sense of order and

meaning among the diverse moments of lived experience.

Although A Million Windows’ allusion to Henry James’s New York preface to Portrait of a Lady

is made explicit in the novel’s title and epigraph, it is perhaps

another of James’s works that exerts the most profound influence on

Murnane’s novel. There are hints throughout A Million Windows

that point to this other text. The most explicit occurs when the

narrator expresses a wish to attain a very specific kind of aesthetic

effect:

I have wanted, for almost as long as I have

been a writer of fiction, to secure for myself a vantage-point from

which each of the events reported in a work of fiction such as this

present work, and each of the personages mentioned in the work, might

seem, at one and the same time, a unique and inimitable entity

impossible to define or classify but also a mere detail in an intricate

scheme or design.

Murnane articulates here the desire

to acquire a perspective or ‘vantage-point’ that will enable him to

maintain the particularity of the various events and characters within

the work of fiction, while simultaneously entirely resolving these

particularities within an overarching plan or pattern. For Murnane’s

narrator, this synthesis would function as something like the ideal or

absolute horizon of fiction. Fiction, because it is not subject to the

rules and constraints imposed by logic, provides a unique form that can

bridge the insurmountable gap between the particular and the general.

While

Murnane’s narrator’s idea draws on a rich vein of aesthetic ideas that

can be traced back to German Romantic theories of the novel – compare

Schlegel’s famous dictum that any ‘theory of the novel would have to be

itself a novel’ – I experienced a sort of déjà vu in reading

the above passage that I could not account for until, entirely by

chance, I happened to reread Pascale Casanova’s essay ‘Literature as

World’, which contains the following account of the central metaphor in

Henry James’s story ‘The Figure in the Carpet’:

In

his story, ‘The Figure in the Carpet’ . . . Henry James deploys the

beautiful metaphor of the Persian rug. Viewed casually or too close up,

this appears an indecipherable tangle of arbitrary shapes and colours;

but from the right angle, the carpet will suddenly present the attentive

observer with ‘the one right combination’ of ‘superb intricacy’ – an

ordered set of motifs which can only be understood in relation to each

other, and which only become visible when perceived in their totality,

in their reciprocal dependence and mutual interaction. Only when the

carpet is seen as a configuration . . . ordering the shapes and colours

can its regularities, variations, repetitions be understood; both its

coherence and its internal relationships. Each figure can be grasped

only in terms of the position it occupies within the whole, and its

interconnections with all the others.

My suspicion is

that the desire articulated by Murnane’s narrator to resolve the

particular and the general within his fiction is intended precisely as

an oblique reference to the metaphor of the ‘Figure in the Carpet’. The

link is never explicitly made (as I have already noted, Murnane is fond

of withholding the names of sources), but I think there are several

circumstantial details which support the notion that James’s metaphor of

the Persian rug is every bit as influential for A Million Windows as the House of Fiction.

First

of all, there is the striking correlation between the desire expressed

by Murnane’s narrator and James’s metaphor. In both, elements which

appear as a series of ‘unique and inimitable’ entities are subsequently

revealed as the ‘superb intricacy’ of a larger design that can be seen

to unite them when viewed from the right perspective. Given the specificity of both notions, as well as A Million Windows’

explicit debts to James, it is very difficult to believe that the

correspondence with ‘The Figure in the Carpet’ here is accidental.

The

unstated connection between the two works becomes clearer when one

considers the subject-matter of ‘The Figure in the Carpet’. The story is

narrated by a book reviewer who publishes what he considers to be an

excellent analysis of the most recent work by the novelist Hugh Vereker.

But when the narrator subsequently encounters him at a party, Vereker

notes that the review – like all reviews of his work – has failed to

perceive the

idea in my work without which I wouldn’t

have given a straw for the whole job . . . It stretches . . . from book

to book, and everything else, comparatively, plays over the surface of

it. The order, the form, the texture of my books will perhaps some day

constitute for the initiated a complete representation of it. So it’s

naturally the thing for the critic to look for.

The

search for this hidden ‘idea’ within Vereker’s books, which elsewhere he

terms his ‘exquisite scheme’, becomes the overriding passion of several

characters in the story. While two of the searchers are initiated into

Vereker’s secret, both die without revealing the pattern to the

narrator.

In other words, James’s story is intimately concerned with the notion of authorial intention

and more specifically the way in which authorial intention might be

either withheld or kept remote from readers. This idea resonates with

the irresolvable gap between ‘the discerning reader’ and ‘the breathing

author’ that A Million Windows obsessively explores. Again,

given the novel’s repeated invocation of James, the overlap here seems

to be far from coincidental. I suspect that A Million Windows

refers to ‘The Figure in the Carpet’ obliquely rather than explicitly

because this ‘secret’ invocation is the only way to keep faith with the

effect of James’s original. In going unnamed, James’s story functions as

a material absence within Murnane’s text, which is only appropriate for

a story that rehearses exactly this material absence of authorial

intention; ‘The Figure in the Carpet’ becomes the secret or hidden idea

within A Million Windows, much like Vereker’s secret ‘exquisite pattern’ within ‘The Figure in the Carpet’ itself.

That

Murnane’s novel might contain such a ‘secret’ allusion is hardly

surprising. His works have often referred to various forms of secret

knowledge, and the narrators of his novels frequently articulate a

desire to share some unnamed secret with one or a series of different

female characters. In a recent issue of the journal Music and Literature,

Murnane noted that, within the many filing cabinets that (somewhat

infamously) constitute his writerly archives, there exists a folder full

of ‘messages written . . . to an imaginary future reader’, which is

entitled Titkos Dolgok, a Hungarian phrase meaning ‘secret

matters’. Not only does this testify to Murnane’s unusual desire to

continue shaping his reception posthumously, it also emphasises yet

again the importance of omission – especially the withholding of

essential, contextualising information – as a formal and rhetorical

strategy within Murnane’s writing.

The importance of such secrets is reaffirmed by the ending of A Million Windows,

which – perhaps surprisingly, given the self-reflexive and discursive

nature of the book – concludes with the narrator (who, let us recall,

resembles but is emphatically not the same as the real Gerald Murnane)

revealing the details of a traumatic familial experience. At the age of

69, the narrator discovers a deeply unsettling secret about his mother

that revises everything he knew about his childhood. In what appears to

be a clear example of life imitating art, the secret divulged at the

climax of A Million Windows reveals the previously obscured

‘figure in the carpet’ within the narrator’s own life, which can only be

perceived from the perspective offered by this revelation. In this

gesture, James’s Persian rug metaphor is appropriated in the same way

that the ‘House of Fiction’ metaphor was.

In A Million Windows,

the ‘figure in the carpet’ – that personal obsession which motivates

the author and provides the pattern that unites his seemingly disparate

works of fiction – is obscured not only from the reader, but also from

the novelist himself, who can uncover the thread of this pattern only

through the process of writing and its slow accrual of unexpected

connections: ‘If you write about something for long enough, you will

find that it is connected to everything else.’

In this sense, A Million Windows

does not simply call into question – as so many have done before – the

possibility of excavating authorial intention from a text. It suggests,

or at least seems to suggest, that authorial intention is actually created

through the writing and production of the text itself. More

importantly, as the novel’s revision of material from Murnane’s earlier

novels suggests, intention itself may be generated retrospectively, as

ideas, characters and scenes are placed in new contexts that enable them

to derive entirely new meanings. If A Million Windows is, as

it appears to be, a late reflection on the artist’s own method, it is

also an acknowledgment of the necessarily contingent nature of that

method, the products of which can never be anything but a surprise, even

to their own author. - Emmett Stinson

Describing Herbert Read’s English Prose Style, Gerald Murnane once wrote:

The contour of our thought is a magical phrase for me. It has

helped me in times of trouble in the way that phrases from the Bible or

Karl Marx probably help other people.

This approach is at the heart of his newest work of “true fiction,” A Million Windows,

published earlier this year. Murnane’s eleventh book, it follows on

with directions of thought explored continually in his life’s work—most

recently in 2009’s The Plains, but going back as far as 1974’s Tamarisk Row.

Murnane contends that the mind is properly understood as a space, that

reality can be perceived in terms of a distinction between the “visible”

and the “invisible” world, that time is more like a map than a linear

progression of events, and that it is imperative that a work of fiction

should never pretend to be anything other than a work of fiction. A Million Windows dwells

on these ideas, and on Murnane’s usual fixations: imagery, women, and

horseracing. But it’s also about reluctance, trust, and concealed pain.

If you aren’t familiar with Murnane, you’re far from alone. Although

he’s won numerous awards, and received much attention from writers and

academics like Teju Cole, J.M. Coetzee, Northop Frye, Frank Kermode,

Imre Salusinszky, and Kevin Brophy, he doesn’t have a large readership.

What’s more, he intends to be mysterious. To borrow his phrase, he has

structured A Million Windows—as well as a great deal of his

public presence—on “the withholding of essential information.” Without

very much effort, you can find biographical information. He was born in

Coburg in 1949 and he has spent nearly all of his life in Victoria. He

has never travelled by aeroplane. He married Catherine Lancaster in 1966

and had three sons, and lived in Macleod until 2009, when he moved to

Goroke, in north-west Victoria. He appeared in the 1989 documentary Words and Silk. And yet these details seem to reveal almost nothing about him. In a brief interview for the ABC’s The Writer’s Room,

he shows the camera his violin, and comments: “I play it quite often,

but only when no-one can hear me, so I won’t be doing a demonstration

for you.”

A Million Windows is demanding to read, and slow. Its dynamics

of intimacy and distancing can be frustrating, and at the beginning it

doesn’t offer much goodwill, at least as that word is usually

understood. It provokes you to question whether you are a “discerning”

or an “undiscerning” reader, and in the early sections it seems to

anticipate the reader’s prejudices and to reprimand them. Because

Murnane’s narrators disdain film, theatre and (worst of all!) fiction

that pretends to be film or theatre, A Million Windows avoids

scenic form. With one exception, it contains no dialogue apart from that

implied to exist between writer and reader. It deals more in images and

patterns than in plot. As it elaborates on its central image, a distant

house inhabited by many narrators, it becomes increasing challenging

and complex. But nevertheless it’s captivating, and in the end it’s

rewarding. I don’t trust my own discernment enough to provide a

confident evaluation. But if you’re willing to put in the time parsing

paragraph-long sentences, and paging back to earlier sections when

prompted, then I recommend it. - Liam Harper

It’s often said of Gerald Murnane that his mature period began with the publication of The Plains

in 1982. What followed were four volumes filled with metafictional

introspection and a sustained preoccupation with the act of writing that

culminated in Emerald Blue in 1995. When Barley Patch

appeared in 2009, ending a run of some fourteen years during which

Murnane published no fiction at all, it swerved Murnane’s metafictional

focus from the present tense to the present perfect: from the act of

writing, here and now, to the fact of having written much over many

years. In doing so, Barley Patch announced the arrival of Murnane’s late period, a period that continued through A History of Books in 2012 and continues now, this month, in A Million Windows. Of the three volumes that comprise this loose trilogy of self-reflective fictions, A Million Windows

is the most lucidly written, the most conceptually successful, and the

most emotionally invested. It is also what one reader described to me as

“Murnane to the power of Murnane,” making it by far the least likely of

all of Murnane’s books to appeal to readers not already familiar with

him.

A Million Windows takes its title

from Henry James’ declaration that “[t]he house of fiction has in short

not one window, but a million,” and the image that dominates the book is

“a house of two or, perhaps, three storeys” whose occupants are

continually gazing out of its windows at the grasslands that surround

it. Readers of Barley Patch and A History of Books will

not be surprised to learn that these occupants are, once again, the

“personages” and “image-persons” who Murnane’s eloquent yet formal

narrator remains reluctant to identify as characters, but what is

surprising here is who these people are and where they happen to come

from. Although the origins of its title may lie in the work of Henry

James, A Million Windows takes the image of the capacious house

from an article about a Swedish film director who, “late in his career,”

directed “a film set in a castle many a room of which was occupied by

one or another chief character from one or another of the many films

directed by the Swede in earlier years,” meaning that the occupants of

the house are the chief characters and narrators of some of Murnane’s

earlier publications. Most recognisable among them are the narrator of

‘Stone Quarry,’ arguably the finest of Murnane’s short fictions, as well

as middle-aged or elderly versions of Clement Killeaton and Adrian

Sherd — the protagonist of Murnane’s début, Tamarisk Row, published in 1974, and the protagonist of A Lifetime on Clouds, published in 1976. But while the appearances of these characters may make A Million Windows

look like merely the most recent iteration of what Peter Craven calls

Murnane’s “revisiting, with endless variegations and minute tonal shifts

and dislocations and re-emergences of patterning, the apparent tiny

variations of his obsessive compass,” Murnane incorporates them into the

book in ways that have repercussions for re-readings of the books in

which they first appeared.

As they congregate to debate the metaphysics of literature in much the same way that the plainsmen of The Plains

collectively articulate the meaning of a barren landscape, the

occupants of Murnane’s house give voice to various ways of approaching

the activity of writing fiction. Their discussions invariably involve

the close analysis of the most simple and most common elements of

fiction — characterisation, point-of-view, dialogue, plot, theme, and so

on — and they usually conclude with a consideration of the efficacy of a

given element with reference to a particular work of fiction that they

deem either successful or unreadable. Over time, then, they reach a sort

of consensus on the essential elements of a work of fiction, the most

important of which is what Murnane’s narrator calls a “narrative

presence,” “the personage seemingly responsible for the existence of the

text [who is also] seemingly approachable by way of the text or

seemingly revealed through the text and [who] seem[s] to have written

the text in order to impart what could never have been imparted by any

other means than the writing of a fictional text.” Günter Grass’ The Tin Drum

and the work of the Latin American magical realists are thus designated

as fiction written in bad faith, “mere text[s that are] the seeming

work of no recognisable personage,” whereas Henry James, the champion of

the embodied first-person narrator, is held in special reverence. So

while the house of fiction may have not one window but in fact a

million, the discussions of the occupants of Murnane’s house of fiction

bring about the closure of all but one of those windows while at the

same time articulating many ways of appreciating the landscape onto

which it opens.

What, then, of Murnane’s own work, especially his earlier work, when held to the standards articulated in this book? Neither Tamarisk Row nor A Lifetime on Clouds displays a “narrative presence” of the sort that the occupants of the house require in a work of fiction. A Million Windows

therefore seems to be, on one level, an attempt on Murnane’s part to

elucidate and justify the aesthetics of his mature work and so to find

space within his body of work for the markedly different aesthetics of

the two novels he published prior to entering his mature period. The

suggestion that A Million Windows was written with this objective

in view appears early on, when the narrator shares some remarks made by

“a university lecturer in Islamic philosophy” who taught him during his

time as a student nearly fifty years earlier:

He asked [his students] to call to mind a

motor-car travelling on a road across a mostly level landscape. A

person standing close beside the road and looking directly ahead would

be aware for some time that the car has not yet reached him or her,

then, for a brief time, that the car is present to his or her sight and

then, for some time afterwards, that the car is no longer present, even

if still audible. The lecturer then asked us to call to mind a person

looking towards the road from an upper window of a building at some

distance away. This person is aware of the car as being present to his

or her sight during the whole time while it seems to be approaching,

present to the sight of, and then travelling away from the person beside

the road.

What the lecturer shared with his

students is an image of hindsight in its most literal sense, hindsight

of a spatial rather than a temporal nature. One result of the narrator’s

inclusion of this image in A Million Windows is the implication that A Million Windows

itself is looking out on its own author and watching him watch his own

books fly past, over the course of several decades, while he remains

unable to perceive them long beyond the moment of their writing or to

see the place they might come to occupy in the broader landscape of his

life. Yet the narrator assures his readers that he has no desire to

“repudiate any fiction of mine the narrator of which has the viewpoint

described above” — a viewpoint tantamount to third-person omniscience —

“but I have wanted, for almost as long as I have been a writer of

fiction, to secure for myself a vantage-point from which each of the

events reported in a work of fiction such as this present work, and each

of the personages mentioned in the work, might seem, at one and the

same time, a unique and inimitable entity impossible to define or to

classify but also a mere detail in an intricate scheme or design.”

While not exactly rewriting or revising Tamarisk Row and A Lifetime on Clouds, A Million Windows does attempt to incorporate their idiosyncrasies into the design of what has become the Murnane oeuvre,

revisiting Clement Killeaton’s marble horse races and Adrian Sherd’s

masturbation fantasies and then reconceptualising them as early

manifestations of Murnane’s more recent metafictional interests. And

while it does not shy away from the imagistic preoccupations of Barley Patch and A History of Books,

it supplements their associative and recursive reminiscences with

questions about the worth and value of fiction, with backward glances at

bygone literary achievements and cold assessments of the likelihood of

their longevity, which altogether involve its narrator subjecting

himself to emotional risks that make A Million Windows more

emotionally invested than either of its two predecessors. The result is

an account of an author’s vexed ownership of all of the work that bears

his name, a reconciliation of his early aesthetics with those of his

more mature period, and a late attempt to unify, reconsider, and assess

the lasting value of the fiction to which he has devoted his life — all

without ever approaching these subjects directly or free of doubts and

misgivings. A Million Windows is, in a sense, a retrospective

manifesto written with an eye towards retroactive application: the last

word on the work of a writer, written by the writer himself, so as to

force readers to return to the first words he wrote and to cast a shadow

over their readings of all the words that have appeared thereafter. - Daniel Davis Wood

Gerald Murnane,

The Plains. Text Publishing, 2012. [1982.]

‘Murnane is

quite simply one of the finest writers we have produced.’Peter Craven

‘A

distinguished, distinctive, unforgettable novel.‘ - Shirley Hazzard

‘Gerald

Murnane is unquestionably one of the most original writers working in Australia

today and The Plains is a fascinating and rewarding book…The writing is

extraordinarily good, spare, austere, strong, often oddly moving.’ - Australian

A piece of

imaginative writing so remarkably sustained that it is a subject for meditation

rather than a mere reading…In the depths and surfaces of this extraordinary

fable you will see your inner self eerily reflected again and again.’ - Sydney

Morning Herald

‘One of the

strangest novels I’ve ever read. Murnane’s narrator is a film-maker who, in

slow, hypnotic, maddening, recursive prose, recounts his efforts to make a film

about the outback. It’s a story devoid of “events or achievements”. The real

plains are the folds of the brain, which contain the elusive matter of memory.

Murnane, a genius, is a worthy heir to Beckett. All his books are about

hesitation and isolation; he himself rarely leaves home, and has never been out

of Australia.’ - Teju Cole

Wayne Macauley, he of the Most

Underrated Book Award fame, wrote in his introduction to my edition of Gerald Murnane‘s The plains

that “you might not know where Murnane is taking you but you can’t help being

taken”. That’s a perfect description of my experience of reading this now

classic novella. It was like confronting a chimera – the lower case one, not

the upper case – or, perhaps, a mirage. The more I read and felt I was getting

close, the more it seemed to slip from my grasp, but it was worth the ride.

The plains was first published in 1982, which is, really, a

generation ago. Australia had a conservative government. We still suffered from

cultural cringe and also still felt that the outback defined us. All this may

help explain the novel, but then again, it may not. However, as paradoxes and

contradictions are part of the novel’s style, I make no apologies for that

statement.

I’m not going to try to describe the plot, because it barely has one. It

also has no named characters. However, it does have a loose sort of story,

which revolves around the narrator who, at the start of the novel, is a young

man who journeys to “the plains” in order to make a film. It doesn’t

really spoil the non-existent plot to say he never does make the film. He does,

however, acquire a patron – one of the wealthy landowners – who supports him in

his endeavour over the next couple of decades. It is probably one of Murnane’s

little ironies that our filmmaker spends more time writing. He says near the

end:

For these men were confident that the more I strove to depict even one

distinctive landscape – one arrangement of light and surfaces to suggest a

moment on some plain I was sure of – the more I would lose myself in the

manifold ways of words with no known plains behind them.

Hang onto that idea of sureness or certainty.

The book has a mythic feel to it, partly because of the lack of character

names and the vagueness regarding place – we are somewhere in “Inner Australia”

– and partly because of the philosophical, though by no means dry, tone. In

fact, rather than being dry, the novel is rather humorous, if you are open to

it. Some of this humour comes from a sense of the absurd that accompanies the

novel, some from actual scenes, and some from the often paradoxical

mind-bending ideas explored.

So, what is the novel about? Well, there’s the challenge, but I’ll start

with the epigraph which comes from Australian explorer Thomas

Mitchell‘s Three expeditions into the interior of eastern Australia,

“We had at length discovered a country ready for the immediate reception of

civilised man …”. Bound up in this epigraph are three notions – “interior”,

“country” and “civilised”. These, in their multiple meanings, underpin the

novel.

Take “interior”. Our narrator’s film is to be called The Interior.

It is about “the interior” of the country, the plains, but it is also about the

interior, the self, and how we define ourselves. While there are no named

characters, there are people on the plains and there’s a sense of

sophisticated thinking going on. Some plainspeople want to define the plains –

their country, the interior – while others prefer to see them almost as

undefinable, or “boundless”, as extending beyond what they can see or know. The

plainspeople are “civilised” in the sense that they have their own artists,

writers, philosophers, but it is hard for we readers to grasp just what this

“civilisation” does for them. Is it a positive force? Does it make life better?

“Civilised”, of course, has multiple meanings and as we read the novel we

wonder just what sort of civilisation has ensconced itself on the plains.

These concepts frame the big picture but, as I was reading, I was confronted

by idea after idea. My notes are peppered with jottings such as “tyranny of

distance” and boundless landscapes; cultural cringe; exploration and yearning;

portrait of the artist; time; history and its arbitrariness; illusion versus

reality. These, and the myriad other ideas thrown up at us, are all worthy of

discussion but if I engaged with them all my post would end up being longer

than the novella, so I’ll just look at the issue of history, illusion and

reality.

Towards the end of the novel we learn that our narrator’s patron likes to

create “scenes”, something like living tableaux in which he assembles “men and

women from the throng of guests in poses and attitudes of his own choosing and

then taking photographs”. What is fascinating about this is the narrator’s

ruminations on the later use of these “tedious tableaux” which have been

created by a man who, in fact, admits he does not like “the art of

photography”, doesn’t believe that photographs can represent the “visible

world”. The landowner contrives the photos, placing people in groupings, asking

them to look in certain directions. Our narrator says

There was no gross falsification of the events of the day. But all the

collections of prints seemed meant to confuse, if not the few people who asked

to ‘look at themselves’ afterwards, then perhaps the people who might come

across the photographs years later, in their search for the earliest evidence

that certain lives would proceed as they had in fact proceeded.

In other words, while the photos might document things that happened they

don’t really represent the reality of the day, who spent time with whom, who

was interested in whom and what. They might in fact give rise to a sense of

certainty about life on the plains that is tenuous at best.

Much of the novel explores the idea of certainty and the sense that it is,

perhaps, founded upon something very unstable. Murnane’s plainspeople tend to

be more interested in possibilities rather than certainties. For them

possibilities, once made concrete, are no longer of interest. It is in this

vein that our narrator’s landowner suggests that darkness – which, when you

think about it, represents infinite possibility – is the only reality.

The plains could be seen as the perfect novel for readers, because

you can, within reason, pretty much make of it what you will. If this appeals

to you, I recommend you read it. If it doesn’t, Murnane may not be the writer

for you. - whisperinggums.com/2012/11/29/gerald-murnane-the-plains-review/

Gerald Murnane is a most mysterious author of strangely seductive books, and

I’m currently reading Inland,

first published in 1988 and now reprinted as part of the Australian Classics

Library. About 30 pages into the book I had to stop reading to dig out my

reading journal (Vol12, p58) to see what I had written about The Plains,

which I read back in 2007. I thought I’d publish it here, and hopefully

aficionados of Mr Murnane will seize upon my ramblings and set me

straight. Not likely, I know, but strange things happen in the

LitBlogSphere…

This is a strange book. Gerald Murnane won the 1999 Patrick White

Award for under-recognised writers, and until good old Text republished this

1982 novella, it was out of print. It seems to be a parable or an

allegory but of what I am not sure. For some reason it reminds me of

Kafka, but I’m not scholarly enough to know why, except for an incident where

the young film-maker petitioning the Plainsmen dare not leave his seat for

fear of losing his place. After 24 hours he is unshaven and in need of a

pee, but it’s ok because it makes the Plainsmen feel superior. This is

like K waiting on the bench to sort out his petition.

The Plains is set in an imaginary world where there is inner

Australia where the Plainsmen are, and the coast, which has ceased to

be important. The young film-maker, along with many other supplicants

such as designers of emblems, wait to present their projects to the Plainsmen

who come into town every now and again for the purpose of hearing (but mostly

rejecting) the petitions.

Is Murnane mocking the university application process? One applicant

designs a (PhD gone wrong?) program which analyses the interior decorating

choices made since settlement and (in a parody?) makes some kind of sense out

of what were random choices so that the Plainsmen can feel superior to the

others. The young man wants to make a film out of them, handicapped by

his inability to find out the truth about a long-standing (but inane) feud

between the Haresmen (gold) and the Horizonutes (blue-green). This

bit’s very odd. It’s strangely seductive, however…

The writing becomes yet more opaque. The film-maker is

accepted by the one of the landowners and given free rein to research and plan

his film. He is being paid too, but after ten years is still

debating with himself how to do it! The issue seems to be, how to

make the film and its images unique and yet faithful to the ordinariness of the

plains. It also mustn’t be tainted by images from Outer Australia.

Has the film-maker/narrator been sucked into the odd beliefs of these Plainsmen

so that he can no longer be an observer? Is he a lotus-eater?

I’m mystified…

One of the conundrums is that an explanation or theory must not be

complete. So when the landowner expounds his theory of Time as the

Opposite Plain, the film-maker is suspicious that he must be privately really

investigating the other populaar theories because the Time theory is too

complete. Is Murnane mocking arcane academic theorising here?

The wife of the landowner comes into the library, but they never speak

and he knows nothing about her. By the rules of the Plains one entertains

possibilities but there is no need to do anything other than explore

them. So he decides to write some essays exploring a relationship between

them and have it published and reviewed and then placed in the library where

she might find it and read it. But then he decides that he only wants her

to know that he wrote it for her, not to read it so he worries about how he might

get it reviewed without there being any books in existence. For some

reason this sequence reminds me of The Shadow of the Wind, about

the Last Book. Oh, too odd, I can’t penetrate the ideas behind this

book!

The ending is bizarre. Like all the other writers, artists, modellers

etc, the film-maker is required to present a ‘revelation’, attended by the

locals. He gets up and talks about how he can’t possibly film this or

that indefinable aspect of the Plains. They like this, because it’s

impossible to make a film about the Plains, so even though the numbers dwindle

over the now 20 years he’s been there, he always has an

audience. It ends with his patron photographing him filming nothing at

all.

*

Now in 2009 when I know about Calvino, I think The Plains is an

example of postmodernism…but I’d love to be enlightened further. Over to you,

cyberspace.

I'm not

really a fair

dinkum writer. I've stopped short of writing everything I could have

written - Gerald Murnane

Widely

studied in Australian literature departments in the late seventies and

eighties, Gerald Murnane

was touted as an important new voice, someone to watch, perhaps even someone

with the right credentials to one day snag the country’s second Nobel

Prize. Early success never panned out into popular appeal, however, or even

international recognition although for some reason he has always been very

popular in Sweden where he is regarded as a major writer. In 1999 he won the Patrick White Award,

an award given annually to an Australian writer whose work, in the opinion of

the Award Committee, has not received adequate recognition. That seemed an

understatement as most of his works were out of print by that time.

Jump forward

to 2008 and we find Murnane picking up a cheque for $50,000 and an Australia

Council Writers Emeritus Award which recognises the achievements of writers

over the age of 65 who have made an outstanding contribution to Australian

literature and who have created an acclaimed body of work. This year his ninth

novel since 1974, Barley

Patch, is being published. Might a Nobel Prize by about 2020 be a

distinct possibility? We'll have to wait and see. In 2006 Ladbrokes set his odds at

33/1 – surely they must have improved since then.

His lack of

commercial success is likely a direct result of his lack of interest in topical

material although, like Beckett

(who also eschewed topicality in his work), this affords his work a certain

timeless quality. In interview on The Book Show, the full transcript of which

you can read here, he

said:

I call

myself a marginal writer. I don't mean this as a disparagement of other writers

at all, but I'll just say it in relation to myself; I am not the sort of writer

who writes about the things that were yesterday's newspaper headlines. The

things I write about tend to be more private matters. Again, the word

'marginal' comes to mind, but in a strange way my concerns have lasted for … as

the reissue of [Tamarisk

Row] proves, my concerns are still of interest to people, whereas had I

written about yesterday's newspaper headlines I might have been old hat and

passé by now.

He has

always been a determinedly personal writer, fixated on questions of time,

memory, and the self. One could say the same of Beckett and that certainly

never got in the way of him getting a Nobel Prize. I'm not sure what his fan

base was like in Sweden at the time. Needless to say Remembrance of

Things Past would be one of Murnane's desert island books.

In the

introduction to his Oxford monograph on Gerald Murnane, Imre Salusinszky

writes:

Like Blake, Murnane has the

courage of his own obsessions, following them through to their conclusions even

when those conclusions may be unsettling or distressing for the reader; and his

imaginative strength derives from this courage.

I'd like to

hone in on the word 'obsessions' here for a minute for Murnane can certainly be

described as obsessed on a bad day, preoccupied-to-a-fault perhaps on a good

day. Any man who has taken the time to write a history of his bowel movements

since the constipated, white-bread forties (admittedly not published) and has

taught himself Hungarian

without ever intending to visit the country, deserves a second glance. He has

also written 50,000 words on "people who might have loved me",

maintains a file of "miracles", and a "shame" file that

documents the number of times he's put his foot in his mouth. All of this and

more fill seven filing cabinets that line two walls of the plain, suburban room

where he types, one-fingered, behind drawn curtains. "I am a person who

needs to be in control of things," he says, "What you see is

extremely neatly organised mess." That "mess" he expects his

sons to pass onto a library after his death although he says that any

biographer should not hold his breath looking for a file of dark confessions.

Rather than

observing the real world, Murnane prefers to imagine what a person like him

might find if he ventured out. He has hardly left Melbourne since 1949. He has

never been on an aeroplane. He can't understand the workings of the International Date

Line. He has no sense of smell and only a rudimentary sense of taste. He

has never owned a television set. He has never seen an opera. He has never worn

sunglasses. He has never leaned to swim. He cannot understand, nor does he

believe in, the theory of evolution. He has never touched any button or switch

or working part of any computer or fax or mobile telephone. He has never

learned how to operate a camera. Since about 1980 he has never gone into a

library except to attend a book launch or similar event. He believes "that

a person reveals at least as much when he reports what he cannot do or has

never done as when he reports what he has done or wants to do" which is

why when he gave a lecture at the University

of Newcastle in 2001 – that would be Newcastle, Australia

– he included all the above facts about himself. I have no doubt that all are

still applicable.

If you were

only going to read one book by this author it really ought to be his slim 1982

novel, The Plains, the book in which he attained his mature style:

I admired

the plainsmen because from a landscape of very little promise they could get

much meaning. I like to think that from an apparently uneventful life I've got

a great deal of meaning. – An

Obsessive Imagination

The Plains is a dense story about a filmmaker

who spends years researching a film on the seemingly featureless Australian

outback and its people. In place of the salt-of-the-earth sheep farmers one

might expect to inhabit central Australia the narrator encounters an idealised

world filled with aesthetics and intellectuals; wealthy landowners divided into

factions idly speculating on metaphysics; I don't believe there's a sheep in

the whole book.

The book

opens with the following short paragraph:

Twenty years

ago, when I first arrived on the plains, I kept my eyes open. I looked for

anything in the landscape that seemed to hint at some elaborate meaning behind

appearances.

It was his

intention to make a film entitled, The Interior, about the outback and its

effect on those living there. The title itself turns out to be metaphorical.

Murnane

evokes grasslands and prairies, prizing their capacity for abstraction and

indefiniteness, but the plains are also those of language, the "Interstitial

Plain" that exists only as it posits the potentiality of every other

plain, or plane, of existence. – Nicholas Birns, 'Gerald

Murnane. The Plains', New Issues

Plainly he

has some idea of this before he arrives in the nameless "large town"

at the start of the book armed with "folders of notepaper and boxes of

cards and an assortment of books with numbered tickets between their

pages"; he has clearly done his research – at least he believes that he

has.

His first

task, though, is to find a patron; to persuade one of the landowners to

bankroll his project. This problem he approaches in an oblique way by hanging

round the local bars where he jumps on every opportunity to worm his way in

with these men. There are clearly unspoken protocols to be adhered to. He

begins by telling them he is on a journey, a journey that he has already begun

in a far flung corner of the plains that no one has heard of. This was easy

enough because "[t]he true extent of the plains had never been agreed

on" and "many places far inland were subject to dispute":

I told them

a story almost devoid of events or achievements. Outsiders would have made

little of it, but the plainsmen understood. It was the kind of story that

appealed to their own novelists and dramatists and poets.

[…]

The

plainsman's heroes, in life and in art, were such as the man who went home

every afternoon for thirty years to an unexceptional house with neat lawns and

listless shrubs and sat late into the night deciding on the route of a journey

that he might have followed for thirty years only to arrive at the place where

he sat…

This, with

the gift of hindsight, describes not only where we find our unnamed narrator,

well down that imaginary road after twenty years living in the plains, but

also, it would appear, Murnane himself, perhaps even as far back as 1982.

The great

landowners hold audience in an inner room of one of "the labyrinths of

saloon bars on the ground floor of the hotel" in which he is staying. He

waits his turn. And he waits. And waits. The landowners are nothing less than

capricious and when he is finally called we witness the only extended

'conversation' in the entire book. He finds himself in a room with seven

landowners who appear in no great rush to interview him. They just sit around

drinking and talking amongst themselves until finally one man, identified only

as "7th landowner", who up until this point had been lying

on a stretcher, gets up and approaches him at the bar at which point all the

others stop talking. He senses his opening to present his case and steps to the

centre of the bar:

I told them

simply that I was preparing the script of a film whose last scenes would be set

on the plains. Those same scenes were still not written, and any man present

might offer his own property as a location, His paddocks with all their long

vistas, his lawns and avenues and fishponds – all these could be the setting

for the last act of an original drama. And if the man happened to have a

daughter with certain qualifications, then I would be pleased to consult her

and even to collaborate with her in preparing my last pages.

The

plainsmen prize writing but find film too obviously visible. Most aren't

interested but the 7th landowner's interest is piqued (we learn

later that he is an enthusiastic amateur photographer) but before offering him

a position in his household he points out some of the weaknesses in the

filmmaker's pitch:

My proposal

suggested that I had overlooked the most obvious qualities of the plains. How

did I expect to find so easily what so many others had never found – a visible

equivalent of the plains, as though they were mere surfaces reflecting

sunlight? … He believed, nevertheless, that I might one day be capable of

seeing what was worth seeing … [y]oung and blind as I was…

So the

filmmaker moves his things into the man's house but barely leaves his mentor's

library. As the years march on and he gets caught up in the prevalent

philosophising over the nature of the plains. He begins himself to view them as

a metaphor for everything in the lives of its inhabitants and gradually moves

farther and father away from being able to make a start on his film. The

external plains lose their fascination and he begins to see in the way the

landowner hoped he might and explore these inner landscapes. Inner Australia

has become a jumping off point, a point of departure, an approach Murnane uses

in much of his other writing. Discussing his book of stories, Landscape

with Landscape, Xavier Pons makes this observation:

The first

story 'Landscape with Freckled Woman', introduces the narrator and his dreams

of exploring 'inner space' of 'unfolding' the landscape in order to

reach 'the real world' from his vantage point on St Kilda Road in Melbourne.

This 'unfolding' implies a merger of spatial and temporal notions, and concerns

the mental landscape that Murnane in other contexts refers to as 'the plains'.

– Departures,

p156

The

preservation of history is another important thing to the landowners,

"shaping from uneventful days in a flat landscape the substance of

myth". He arrives intent on recording aspects of their heritage but in his

researches he ends up discovering symbols, stories and parables that lead him

down a very different path.

The second

section of the book finds the filmmaker ten years down the line and he's still

not shot any film. He spends his days in his mentor's library. There he becomes

preoccupied with the landowner's wife who also spends some of her day there.

Before you jump to the conclusion that we have the potential for an affair I

should point out that, although they exchange polite conversation at other

times, in this library they don't even acknowledge each other, she spending

most of her time in the rooms devoted to Time: "we never spoke, and even

when one of us looked across the library the other's eyes were always turned to

some page of a text or some page awaiting its text'. For a while the compulsion

to communicate something to her distracts him but it passes.

It's not

giving away anything to tell you that he never makes his film. His life becomes

completely occupied with doing research for it and even after twenty years the

landowner shows no signs of tuffing him out on his ear. His hope is that his

young protégé will finally get to see the invisible. Nicholas Birns, who I

quoted above, says this far better than I can:

That is the

presiding trope of the plains - the search for a meaning beyond the visible,

the projection of the given onto an indiscernible horizon. This quest may be in

vain, or it may actually have an object, albeit occluded and remote. As much as

this search beyond visibility is mocked, Murnane's incantatory tones

simultaneously privilege it.

The plains

have been mapped in previous centuries. This is referred to as the Golden Age

of Exploration. The events in this book take place in the Second Great Age of

Exploration. The plainsmen now employ writers and artists whose remit it is to

interpret the plains and to find new ways of understanding and inscribing this

vast physical space.

With his

project in disarray, the film-maker is eventually prevailed upon by his patron

to take up a camera, and to search for the essence of the Plains within ‘that

darkness’. The patron in turn insists upon photographing the film-maker in the

act of taking a photograph. But in this carefully composed tableau vivant, with

which the novel concludes, the film-maker is posed with his camera reversed,

with his eye not at the viewfinder but at the lens. He is photographed in the

act of photographing his own eye, or indeed what lies behind it. He is about,

‘to expose to the film in its dark chamber the darkness that was the only

visible sign of whatever I saw beyond myself’.

That is, the

film-maker is caught in the act of photographing what it is that is entirely

personal to him, Time. His project has collapsed in the knowledge that he

cannot complete a project based on the unification of space around the common

notion of place, because the unique element of Inner Australia is discovered to

be Time, the Opposite Plain. This solipsistic and isolated gaze of the explorer

of the Second Great Age of Exploration is the antithesis of the empire

expanding gaze of the explorers who drew the maps in the Golden Age of

Exploration.

The book is

also not an easy read and reminds me of parts of Beckett's trilogy. I was

pleased to see that it wasn't just me that sees the Beckett connection:

Imre

Salusinszky's essay on Gerald Murnane bubbles with an enthusiasm which almost

convinced me that I have underestimated the writer. He reads Murnane as a

philosophical writer, placing him in a tradition stretching from Dostoevsky through Sartre and Beckett to Robbe-Grillet and Paul Auster. Undaunted by the resonance

of big names, Salusinszky goes on to link Murnane's name with a range of

philosophers, focussing principally on Derrida. Murnane's

fiction is 'an adventure of consciousness', an exploration of human isolation

in the face of a reality composed of ultimately unknowable structures. – Susan

Lever, 'The

cult of the author', Australian Literary Studies, Oct 93

What I find

amusing is that Murnane himself in his essay, 'The

Breathing Author', which is an edited version of the Newcastle lecture I

mentioned earlier, explains that when he studies philosophy at the University of Melbourne in 1966, after

handing in his first essay, his tutor took him aside and told him that he had

failed to grasp even the basics of the subject. Despite this handicap he

managed to obtain a second-class honours in Philosophy One purely by being able

to recall passages from books and comments made on them by his tutors.

He does hold