Barbara Browning, The Correspondence Artist. Two Dollar Radio, 2011.

excerpt

www.thecorrespondenceartist.com/

barbarabrowning.info/barbarabrowning.info/Welcome.html

"The Correspondence Artist is smart, funny, sexy, knowledgeable, subtle, disturbing, light-hearted, obsessive, and tragic: a comedy that, I surmise, is wholly confessional and wholly imaginary. Readers are urged not to resent a wit superior to their own, since it is deployed entirely for their particular entertainment."—Harry Mathews

For three years, a rather unremarkable woman named Vivian has been carrying on with an internationally recognized artist, largely via e-mail. Fame contaminates things. There are people who stand to profit from the most trivial information about this affair, and others who stand to lose. So she creates a subterfuge: a series of fictional versions of her lover.

There is Tzipi, a beautiful sixty-eight-year-old Nobel-winning Israeli writer; Binh, a twenty-something Vietnamese conceptual artist; Santuxto, a poetic blogging Basque separatist; and Djeli, a brainy Malian "World Music" star - each of whom corresponds to a particular aspect of the character of the unnameable "paramour".

Through her stash of e-mail correspondence, Vivian divulges the story of their relationship, from their first meeting to their jumpy spam filter, which arrests the more explicit notes, leading to Vivian's being held captive in a tiger cage in a Berlin hotel / chased by a Medusa-like woman on a Greek Island / imprisoned by a splinter cell of Basque separatists / interned in a Bamako hospital with a bout of dengue fever.

The Correspondence Artist might be construed as a self-destructing roman à clef, raising questions about the ethical, legal and psychological transgressions of the genre even as it commits and undoes them.

How I Came to Write This Novel

I had long written poetry and non-fiction – particularly experimental ethnography – before attempting fictional narrative. My academic books were often described as having a strong lyrical or narrative strain, but it wasn’t until about 2004 that I began writing fiction in earnest. I think I was moved in part by the catastrophically sad state of global affairs after 9/11. This country’s political response sunk me into a despair I felt I could only write my way out of. I was also the single mother of a wryly ironic son (11 at the time) who dropped devastating one-liners on my lap the way some cats gift their owners with dead mice.

My first manuscript was called Who Is Mr. Waxman? Agents and editors said they liked it but it didn’t really have any plot to speak of so they wondered who would buy it. I turned it into a podcast for my own diversion and so I could move on (www.whoismrwaxman.com). I wrote a second novel – about a spiritist healing clinic in Brazil, led by a guy who channels Dr. Scholl, the famous podiatrist. It was a little weird. I titled it after an obscure biographical tome on Scholl: Man or Myth?

Meanwhile, proving that life is stranger than fiction, my first manuscript (and some poems) brought me into contact with an illustrious international figure who inexplicably wanted to meet me. One thing led to another, and after a series of awkward miscommunications, tender rapprochements, a climactic catastrophe and a rather disappointing denouement, I found myself feeling yet again that the only way out of a sad situation was to write another novel. Writing a fictional work about love, I began to realize how inherently fictional love always is. It was a big relief.

There was one other incident that provoked the idea of the structure of the book. I saw Sophie Calle’s installation, Prenez Soin de Vous, at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. It was about a break-up e-mail she’d received from her lover on her mobile phone (he ended it: “take care of yourself”). She asked 107 women to help her interpret her lover’s e-mail. She said analyzing it from all those perspectives helped her to take care of herself. Right afterwards my son and I went to Harry Mathews and Marie Chaix’s apartment for a glass of wine and I told them, “I have an idea for a novel.” Harry said he thought it sounded like a terrible idea. Who Might Want to Read a Book like This? Because it mixes high-brow (Lacanian psychoanalysis, French feminism, obscure art film) with low-brow (Yahoo!, Cameron Diaz, Mötley Crüe), it will appeal to over-educated readers who aspire to a pop sensibility, and less erudite readers who aspire in the other direction. Because it’s the story of an ordinary 45-year-old woman who gets to sleep with four, count them four, international sex symbols, it will appeal to a lot of 45-year-old women.

In The Correspondence Artist, Barbara Browning’s debut novel, Vivienne has a paramour whose identity must be kept secret. But since Vivienne seems to want to tell us all about him or her, she invents a handful of personas to stand in for her lover: a world music rock star from Mali, an Israeli novelist, a Basque revolutionary, and a Vietnamese artist. Vivienne moves the story deftly back and forth between her fantasy lovers, telling us about their trysts and sharing their discussions on film, contemporary art, jazz, literature, Jacques Lacan, and other topics familiar to the international art intelligentsia. In the hands of many other writers, conversations like these often come off stilted or speechy, but Browning lets Vivienne talk directly to the reader in a natural, comfortable, almost chatty manner that is totally convincing. She asks us questions and worries, for example, that we might not be following her explanations of Lacan. “Am I losing you?” she asks us as she attempts to summarize Lacan’s observations on the various meanings of the word “letter.”

The Correspondence Artist declares its ambitions and establishes its roots through two recurring literary references: the mostly long-distance romance between Simone de Beauvoir and Nelson Algren as seen through the posthumous publication of her letters to him and as depicted in her novel The Mandarins, and the Edgar Allan Poe short story “The Purloined Letter,” but as seen through an explication of the story offered by Lacan (see his Seminar on “The Purloined Letter). Browning, who has a PhD and teaches at NYU’s Department of Performance Studies, is among a growing number of academics who have set up camp in the forest of fiction as a way of breaking free from the traditional model of academic writing. She moves seamlessly between critical theory and pop culture and I will confess that I rather liked getting my dose of Lacan this way.

Woven into her narrative of love, sex, and miscommunication are emails to and from Vivienne’s various lovers – hence the book’s title. But, with the exception of her spam filter,which has a habit of arbitrarily snagging important messages from her view with unfortunate results, email fares no worse than old fashioned snail mail in its ability to stir up misunderstandings between separated lovers.

On my way home I wrote Djeli from the airport a pretty heartfelt message about our time together, how close I’d felt to him, and because I was feeling that close, I made the mistake of raising the subject of a couple of moments of seeming miscommunication in our sex. I’m sure you know what I’m talking about – this kind of thing happens to everyone once in a while. Of course it’s best just to let these situations pass. The worst idea is probably to touch on it, however tenderly, in an e-mail.

Vivienne is one of those post-modern narrators who knows she is writing a novel. She is so eager to make up fictional characters for our amusement that it isn’t surprising when she ultimately tells us she has “gotten attached in different ways to all of the characters in this novel.” Fiction, like letter writing, can be a form of love-making. In something of an echo of the movie Groundhog Day, Vivienne regales us with incidents that recur over and over with slight variations with each of her lovers. Her blend of worldly sophistication and guileless honesty even leads her to this admission:

It’s probably pretty evident that this novel was constructed out of some fairly questionable knowledge gleaned from Google, a small, arbitrary stack of library books, a few Netflix DVDs, and my bin of sent e-mails. I’m clearly not an expert in Israeli political fiction, Basque separatism, experimental digital art, or Malian pop music. I know a little about all of these things, but not a lot.

As I finished The Correspondence Artist I couldn’t help but compare Browning’s book with another that I just read – Ben Lerner’s over-hyped and nearly insufferable novel 10:04, which I found only marginally better than his first one, Leaving the Atocha Station. Both have hyper-smart narrators who are anxious to show off their knowledge while telling us about the novel they are writing and which we are reading. But Browning effortlessly and entertainingly manages to juggle her metafictions while Lerner only manages to suck the life out of his.

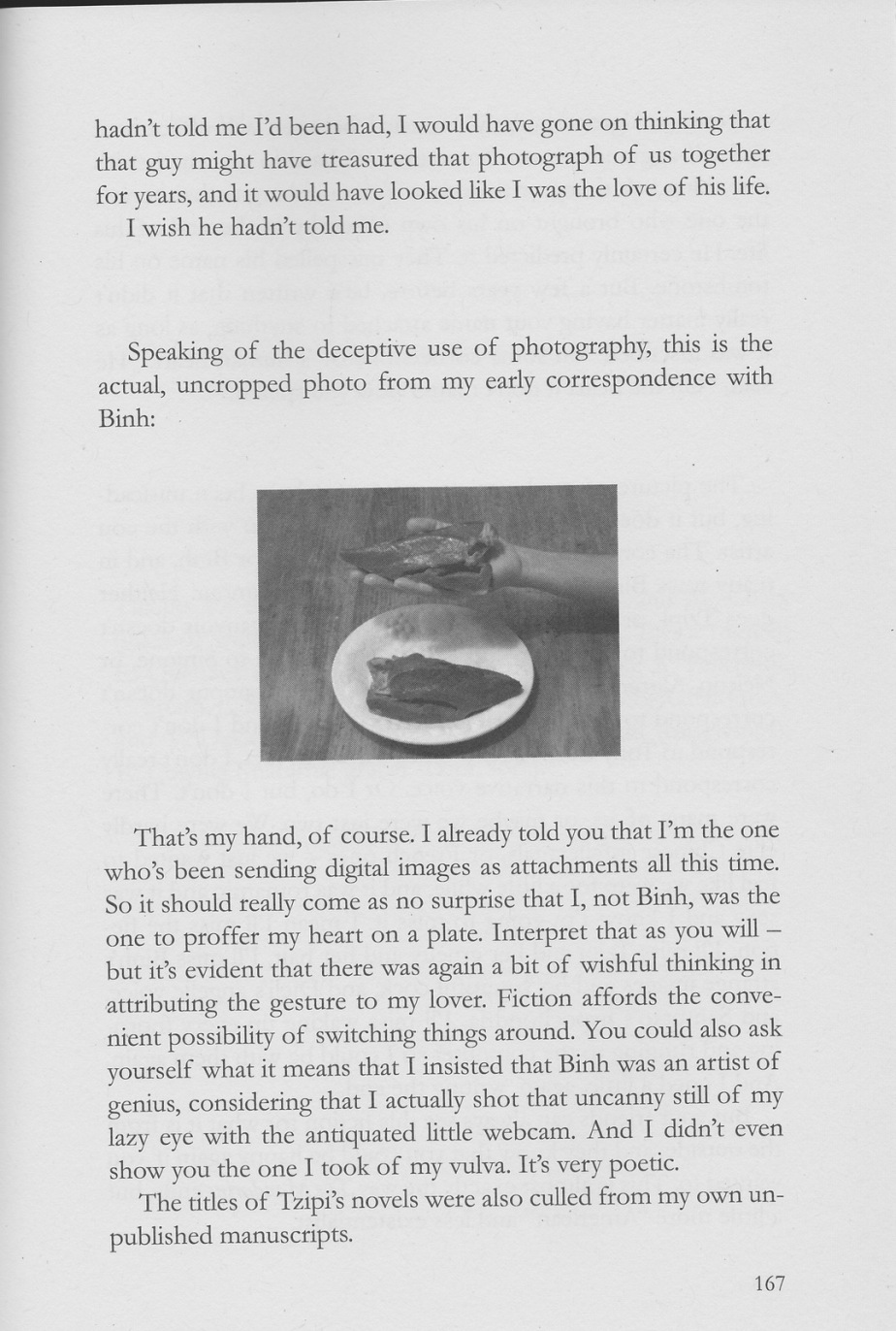

Browning is also much smarter about the inclusion of embedded photographs in her book than Lerner, who can’t seem to think beyond literal illustrations. Here’s just one example from The Correspondence Artist. Early on, Vivienne tells us that Binh, her Vietnamese lover, has sent her an email that consisted of “just an embedded image, beautiful, innocent, saturated with color: a split beef heart on a piece of chipped china.”

But

near the end of the book, she explains that she was being deceptive and

she shows us the photograph again, but this time uncropped. “That’s my

hand, of course. I’ve already told you that I’m the one who’s been

sending digital images as attachments all this time. So it really should

come as no surprise that I, not Binh, was the one to proffer my heart

on a plate.” It’s a bit like the magician who repeats her trick a second

time, telling us to watch carefully and she will reveal the secret.

Instead of becoming deflated and disillusioned with magic, this member

of the audience gained new respect for the tools with which the magician

performs and swore he will be more attentive the next time. Good

lessons for any reader.

But

near the end of the book, she explains that she was being deceptive and

she shows us the photograph again, but this time uncropped. “That’s my

hand, of course. I’ve already told you that I’m the one who’s been

sending digital images as attachments all this time. So it really should

come as no surprise that I, not Binh, was the one to proffer my heart

on a plate.” It’s a bit like the magician who repeats her trick a second

time, telling us to watch carefully and she will reveal the secret.

Instead of becoming deflated and disillusioned with magic, this member

of the audience gained new respect for the tools with which the magician

performs and swore he will be more attentive the next time. Good

lessons for any reader.

- sebald.wordpress.com/2014/11/18/the-correspondence-artist-by-barbara-browning/

Barbara Browning’s The Correspondence Artist applies stylistic juxtapositions in welcome and unexpected ways. This novel, Browning’s first, is experimental in structure yet casual in tone. It’s an extended metaphor of a book that nonetheless abounds with insider details, art-world cameos, and precise images — even resorting to the occasional still frame to etch a particular scene onto the mind of the reader. The premise is simple; the narrator, a writer named Vivian, has had (or, possibly, is having — whether or not the central relationship has ended or remains intact is one of the book’s central questions) a relationship with someone, referred to only in the novel as “the paramour.” The paramour’s identity is concealed to protect him or her, and so Vivian recounts the story of their meeting through four proxies: artists, writers, and revolutionaries of varying ages, genders, and geographic origins.

It’s something of a dance, then: watching Browning, through Vivian, restage certain emotional moments through vastly different setpieces. A case of missed communications leading to a stumble in the relationship is rendered four different ways: in one a sort of performance-art comedy of errors involving hotel rooms, video cameras, and a public art installation; in another, Vivian finds herself under siege by political radicals. Among the constants here are Vivian’s relationships with her teenage son Sandro and friend Florence; the format, with memories punctuated by emails and the occasional image, remains constant as well, whether the lover Vivian describes is a Basque separatist or an Israeli novelist.

The structure of the novel leads to few revelations: here, the story really is in the telling, with the book’s depth coming from the densely wrapped strata of questions it raises. This is a layered work, with occasionally blurred lines between the stories of the four fictional lovers, and even between the stories Vivian recounts and the Browning-written novel before us. (Specifically: it’s a bit surreal to see both Paul D. Miller and Harry Mathews make appearances within the text after reading their enthusiastic blurbs on the novel’s cover.) Characters real and fictional write themselves into novels within the novel (and outside of it; that Subcommandante Marcos — who has, in fact, written a detective novel in collaboration with Paco Ignacio Taibo II — makes an appearance is surely no accident.)

Also summoned up are issues of ethics — Vivian meets many of these fictional lovers after first encountering them in a journalistic capability. That break with convention — the line between interviewer and interviewee eventually dissolving after a meet-cute — seems, in some ways, to mirror the novel’s own break with traditional narratives focusing on the beginnings and endings of relationships. Yet it also raises certain issues that either Browning or Vivian don’t readdress.

Given the scope of The Correspondence Artist, certain other understated issues may also prompt frustration. This is, fundamentally, a novel set among a very particular milieu. And while it does raise questions of family, of trust, of intimacy — and, of course, of identity. Class, though, is something of the elephant in the room here — I’m reluctant to use the phrase “jet-setting lifestyle,” but there is something of that present. We are among the creative class in this novel (and in the stories told within it), but it’s a very well-off division of it.

To be fair, Browning is after questions of distance here — all of the fictional lovers mentioned by Vivian are separated from her by continents and oceans. Email is the primary means of communication, and the fact that a spam filter looms large in many of these narratives suggests that, while some of the concerns here may be timeless, others are very much of the moment. This is a fully globalized novel, and many of its concerns have a contemporary urgency. How best to maintain a relationship with someone on the other side of the world? To what extent do we forget the looks of our paramours, to the point where they might begin to lose distinction, to vanish into our minds or become indistinct, to become suffused with the accumulated details of other lives? The occasional appearances by celebrities and Browning’s ability to convincingly create authentic-sounding artists may delight or frustrate, but it’s The Correspondence Artist’s exploration of fragmented identities that ultimately endures. - Tobias Carroll

Writing about the Internet is boring. Ostensibly it’s all about communication but viewing it or describing it is describing people sitting still, in silence, looking at a screen. Plus writing about the net is usually obsolete as soon as it hits the page.

Barbara Browning’s first novel The Correspondence Artist is a mysterious romance we only get to see in the rarified aether of online communication, and she capably relays the sensation of that perilously ambiguous world. Addressing the audience directly in the beginning, her narrator Vivian explains that what follows is a one-sided history of her ailing romance with a nameless "paramour," an internationally renowned artistic figure. Since this person places a very high premium on privacy, she’s decided to create not one but four separate fictional lovers behind whom she can disguise the real details of the affair. But these different characters also allow her to try and explain various parts of her lover’s real inconsistencies and endearing flaws.

While the fictional four are all fantastically different in surface respects, at the core they are the same solitary person, like a four-leaf clover. Behind the different cosmetic masks is the real paramour with all the real skips and pops we notice when we’re falling in love with someone. Whether the paramour is a novelist, an avant-garde video artist, a musician or a poetically-minded revolutionary leader; an Israeli, Vietnamese, a Basque or Malian, a man or woman somewhere between their early twenties or late sixties -- that real central paramour is a doting parent who’s in Lacanian therapy, a teetotaler prone to overwork who rarely visits the US, an occasional accidental sexist whose political opinions can veer murkily into hypocrisy. Vivian and the paramour enjoy intense sex when time and geography allow, and share an off-handedly erudite e-mail correspondence the rest of the time. They’ve each settled into the territory of “I love you, but I’m not in love with you.”

Browning tells the tale of their first meeting four times, each one different but identical in its main details. Later on an aggressive spam filter lands Vivian in serious peril, again in four different but oddly similar ways, each flavored by that version of the paramour; the politico deposits her in the hands of sinister Marxists, her novelist accidentally summons up the specter of a wrathful mythological villain and so on. It’s like one of those logic puzzles where Sally doesn’t ride the blue or red bike, and the person who rides the yellow bike does so before Friday, and Jerry rides on the day after the white bike is ridden. That is, if you decide to believe that there is any one composite "real" version of the paramour.

The one most immutable, concrete character in the book is Vivian’s teenage son Sandro. Growing up with a single mother in Manhattan, Sandro is casually and unpretentiously hip, and bemusedly in the know about many of the details of his mom’s relationship. An intelligent kid who is his mother’s anchor in the many-veiled versions of her life, that relationship reminded me of Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai. Not simply because it’s a story about a single woman raising an intelligent kid (with a mysterious pseudonymous lover); partially it was the cast of figures being sorted and shuffled by their qualities, but primarily both narrators are so offhandedly intelligent and well-read without condescension that it makes the book a pleasure to read. Both novels directly address the reader, and frequently and unapologetically leap into passages about rarified intellectual or cultural subjects.

One of the central reoccurring subjects Vivian comes back to throughout the book is the letter-heavy love affair between Simone de Beauvoir and Nelson Algren. The Correspondence Artist, just like A Transatlantic Love Affair, only contains one half of the crucial conversation. Browning skillfully makes this a strength, since only reading her side of the emails allows the paramour to remain anonymously any or none of her fictional four. This kind of writing can get tricky -- she almost always manages to refer to her lover in gender- and culturally-neutral terms, although a slip here or there seems like a sly clue. In parts of the book she seems to be wishing her real lover were more like one or another of her imagined ones (who hasn’t been there?). I’ve been told that it helps if a writer feels some affection for all their characters -- and Browning clearly does.

It’s tough to say if Barbara Browning had a particular real-life person in mind behind the mask of the paramour. It was also tough not to try and guess whom that figure might be while reading the book. But if it’s ultimately a novel about the mysteries of communication and your lover’s true identity, I suppose that kind of information is *spoilers* - Ben McLeod

In the late 1940s, Simone de Beauvoir and Nelson Algren conducted a torrid affair that went bust thanks in part to a bit of miscommunication. When the French feminist described herself as “your loving wife” to the hardscrabble Chicago novelist, she was just playing cute in her second language, not actually asking for a ring; the letter Algren wrote back proposing marriage deserves a display in the Museum of Awkward Moments.

Barbara Browning routinely mentions the Beauvoir-Algren letters in her debut novel, The Correspondence Artist, which makes sense: The book, like the affair, is wrapped up in powerful feelings of disconnect, confusion, and sexual need. The heroine, Vivian, is a middle-aged writer who’s ending a years-long affair she’s conducted with a famous artist, primarily over e-mail. To conceal the lover’s identity, she imagines him or her as one of four other famous artists: The lover is alternately a Nobel-winning Israeli novelist, a hot young Vietnamese-American visual artist who hangs out with Matthew Barney and Björk, a Basque separatist, and a Malian rock star. The true identity of the lover doesn’t matter, Vivian means to say; what does is the isolation that courses through her as she recalls the relationship’s demise and how she was left feeling like a second-class citizen. “It makes it sound like I have a secret and exciting love life,” she writes. “I guess I do, from a certain perspective, but…in most respects it’s as stupid, awkward, and frustrating as anyone else’s.”

Still, imagining a failed romance through four different characters does give the story an unusual liveliness, and Browning expertly filters critical moments through each imagined lover. A miscommunication with the visual artist leads to an embarrassing moment where a live feed of her masturbating is projected in Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz, while the same miscommunication, imagined with the musician, leads to a case of dengue fever. The structure is unwieldy, but never confusing, and it helps put Vivian into focus: When the lover could be anyone, what’s left is the sense of the frustration and erotic charge that suffuses this push-me-pull-you romance.

So, it’s a little frustrating to see Browning muddy Vivian’s emotional state to engage in some metatextual fun and games in the book’s closing chapters. A riff on Faulkner leads to an overwritten attempt to ventriloquize him instead, and some musing on the Marx Brothers prompts a farcical Monkey Business-esque plot turn. Why abandon the sincerity that was so carefully cultivated early on? Vivian is happy to explain that it has something to do with the “essential poetic disintegration of reality,” socialist politics, and Lacanian therapy, all of which claim a larger portion of the stage in the closing pages.

But the earnest and engaging writer, single mom, and burned lover who showed up in the beginning gets lost. At first the four-lovers conceit seems like a symbol of how faith in love can so easily gets split into pieces—a lover rhetorically drawn and quartered. By the end, it feels like a display of narcissism: Why have just one famous lover attracted to you when you can invent four?

-

Barbara Browning, I’m Trying To Reach You. Two Dollar Radio, Reprint edition, 2012.

www.imtryingtoreachyou.com

at issuu

First Michael Jackson, then Pina Bausch. Next is Merce Cunningham.Gray Adams, a former dancer with the Royal Swiss Ballet at work on his dissertation at NYU, has a theory spurred by countless hours of YouTube-based procrastination: someone is killing these famous dancers! (And he may bear an uncanny resemblance to Jimmy Stewart, circa Vertigo.)I'm Trying to Reach You is a moving and candid contemporary look at how we process grief, as well as how we love and communicate with one another.In the author's consideration of gender, race, and class, she also attempts to relate what it truly means to be an American in this modern age.

“Exquisite storytelling at its finest. I’m Trying to Reach You cultivates our relationship

addiction with YouTube and our desire for interconnectivity while illuminating

what it means to strive, cope and love with all of our heart, brain, body and

soul. It is all here. Browning writes with humor, wit, grace and passion to the

human purpose, mortality and the joys of existence. Start reading.” – Karen

Finley

“The writing of Barbara Browning reminds me of the

young, spirited Françoise Sagan whose first three novels, Bonjour Tristesse (1954), Un certain

sourire (1955) and Aimez-vous Brahms? (1959),

were written when she was still in her teens and early twenties and are beyond

brilliantine. The film version of Bonjour Tristesse

(1957) was directed by Otto Preminger starring a lovely Jean Seberg. If only Mr.

Preminger were alive today to direct a filmed adaptation of Ms. Browning’s I’m Trying to Reach You. That would be granada.” – Vaginal

Crème Davis

“[Browning’s] books aren’t even just books, they’re

multimedia art projects. I think I love this book so much because it contains

intimagions of the potential of what books can be in the future, and also

because it’s hilarious.” - Emily Gould, BuzzFeed

Set in New York City, Browning's media-saturated and humorous second novel (after The Correspondence Artist) follows Gray Adams, a 46-year-old gay African-American ex-ballet dancer, as he revises his dissertation on semaphore in dance during a post-doc at NYU. The novel opens, however, in Zagreb, Croatia at an international performance studies conference on the day that Michael Jackson dies. Gray, like many others, takes to YouTube to cope and stumbles upon a mysterious video in which a woman in a black leotard dances to the music of Erik Satie; the connection to Michael Jackson is tenuous, though the danseuse does moonwalk. In subsequent chapters, other cultural icons perish—including modern dance choreographers Pina Bausch and Merce Cunningham, and famed inventor of the solid-body electric guitar, Les Paul. Gray begins to follow the YouTube channel of the enigmatic dancer, who seems to create new videos related to each death. To add to her mystique, Gray notices that one of her YouTube commenters is taken with her, while the other hints at murderous intent. As Gray muses on the meaning of the videos, the extent of his loneliness comes to light, and Browning's characteristic theoretical overlays complicate and deepen his experiences. Deftly blending highbrow intellectual concerns with the informality of Facebook-era communiques, Browning's newest is as entertaining as it is thought-provoking. - Publishers Weekly

My friend Sam and I were recently talking about the point where an action turns into a performance. The conversation was prompted by his story, about a night last winter when he walked home through Chicago’s icy streets and Sam started kicking a piece of ice to preoccupy himself along the way. At a certain point, when he decided to kick the ice home, the game took on a more serious quality and became a performance. He took pictures on his phone. He recorded video footage. He wrote a blog post about it the next day. When a pedestrian walking in the opposite direction passed him and kicked the ice back toward Sam, this interaction became part of the performance, too. What was it that made my friend’s playful action into art? It seems, quite simply, his quality of attention and focus, and this documentation.

In one sense, writing isn’t very different. Writers sit habitually before their keyboards (or with a pen and paper at the ready), and in doing this attempt to isolate moments from life and reframe them on the page. Another way of understanding the performative in the literary is through John Cage, who said that literature, “if it is understood as printed material, has the characteristic of objects in space, but, understood as a performance, it takes on the aspects of processes in time.” The blurring of time and space, and of art and life, are central to Cage’s conception of art, that “art should not be different [from] life but an action within life.” An action as habitual as brushing your teeth can become art if a certain conscious attention is paid to it. Alan Kaprow, Fluxus member behind the Happenings, made a point to say that an artist’s renewed awareness of performing a repetitive action can reinvigorate this action, that “Ordinary life performed as art/not art can change the everyday with metaphoric power.”This blurring of art and life by turning the everyday into art is an idea central to Barbara Browning’s latest novel, I’m Trying to Reach You. The novel borrows its title from the working title of a book that the narrator, dancer-turned-academic Gray Adams, is writing from his dissertation, during a post-doc year in NYU’s department of Performance Studies. Gray is never not researching. He’s always observing, texting, photographing, and scouring the Internet for material, especially YouTube, his “first resort in dealing with questions from the answerable to the unfathomable.” In these preoccupations, he ends up far more focused on novel writing than fulfilling his academic obligations, and as a result he leans heavily on this fiction to generate his academic work.

For an academic who comes to performance through what he calls “the more literal and slightly less fashionable side of the spectrum” of performance dance, Gray is a virtuoso at dissolving boundaries and conflating art and life. His novel largely borrows from his life. He begins writing in the summer of 2009, when he is in Zagreb attending an international performance conference on the day that Michael Jackson dies. Jackson’s death fuels Gray’s first line, “I was in Zagreb the day Michael Jackson died,” and from this the rest of the novel unfurls. Jackson’s demise is significant not only because of its untimeliness, but also because his death marks the first of three innovative dancers. Pina Bausch and Merce Cunningham follow in a matter of weeks, and this has Gray turning to YouTube for answers regarding the cryptic cosmic meaning contained within the coincidence.

It’s through his YouTube investigation that Gray discovers the mysterious and captivating videos of a dancer, posted by falserebelmoth. Gray is accustomed to reading messages into contemporary dance – his dissertation focused on semaphore mime in contemporary ballet choreography – and he reads into falserebelmoth’s dance, too, which includes a brief moonwalk homage to MJ. Gray observes that the dancer’s “gestures become more idiosyncratic and mysterious, as though she were trying to communicate some information.” Subsequent videos are posted with each death, and Gray lurks in an attempt to decipher their hidden meaning, viewing each video multiple times and scouring the comment thread. Gray’s desire to uncover a message, coupled with his multiple, seemingly related run-ins with a Jimmy Stewart lookalike, keeps him curious and on his toes. It also provides him with an abundance of material for his novel.

Browning integrates social media and contemporary modes of communication within the text as if it were second nature. Culturally we’re so constantly immersed in multiple layers of media – text messaging, emailing, chatting, posting photos and videos, and yet so few books actually convey this fluency with digital media (as was noted in a recent Millions essay, on the role of technology in fiction). But Browning pulls this off seamlessly. Images and video stills are integrated within the text. A picture of prized heirloom tomatoes snagged from a farmers market is snapped for later posting on Facebook; there are fruitless, patience-trying digressions within comments sections; text messages are volleyed back and forth across the Atlantic between Gray and his Swedish boyfriend; and Gray is always taking photos – to document the everyday, to research, to examine, to immortalize. Such is the case with the picture Gray takes of a man riding a stationary bike on his patio across the courtyard (also a nod to Hitchcock’s Rear Window). He reflects:

Documenting the guy across the courtyard was a way of gathering information for the book I might write. A kind of research. But after I’d taken the picture, I felt a little creepy. I made myself nervous wondering if anybody on the other side had noticed me taking the picture, and if they might have taken a picture of me taking a picture of the guy on a stationary bike.

This kind of lurking, in life and online, is something Gray touches on during his final academic talk of the year. He borrows heavily from Lauren Berlant (whose essay he found last-minute via Google search) when he says that we are increasingly “overheard and understated.” Gray is constantly listening in and observing others, whether they’re across the courtyard or leaving coded commentary, to fuel research for his novel, his academic papers, his performances. They are one in the same.

Life material becomes novel material, both for Gray Adams, and for Barbara Browning. Browning, too, was in Zagreb attending the very same conference on the day that Michael Jackson died. Browning, like her narrator, is an academic who teaches at the same university, in the department of Performance Studies. It’s significant to note that Browning refers to I’m Trying to Reach You, “not [as] a novel but a multimedia project linked to a series of chamber choreographies.” New digital media figures centrally within I’m Trying to Reach You; it provides the framework for Gray’s existence, as a tool for communication, for finding and archiving information, for documenting, for seeking solace while searching for an answer he has yet to find. But it dually becomes a medium for obfuscation, for misreading, for unleashing a labyrinth of potential meanings and inferences that may or may not exist.

Images of the twelve “chamber choreographies” that Gray watches are printed within the text. The videos are also posted for the reader to view on YouTube. In these videos, Browning is falserebelmoth, the dancer that Gray is watching. And so, if Gray Adams is Browning’s doppelganger, then falserebelmoth is another incarnation of the author, too, and through Gray’s gaze, she’s watching herself. By viewing Browning’s intimate dance performances, which take place in domestic quarters, we readers are made even more keenly aware of Browning’s multiple performances, the way that she parlays life into her art, and that every aspect of this novel constitutes an element of Browning’s performance. This fittingly is in line with Merce Cunningham’s emphasis of “each element in the spectacle.” And all the while, we readers are lurking and overhearing, watching Gray who is watching others, following Gray to YouTube, watching Browning as falserebelmoth dance in a bathtub. And by doing so, we are made newly aware of our own constant lurking, within the book and within our own lives too. - My friend Sam and I were recently talking about the point where an action turns into a performance. The conversation was prompted by his story, about a night last winter when he walked home through Chicago’s icy streets and Sam started kicking a piece of ice to preoccupy himself along the way. At a certain point, when he decided to kick the ice home, the game took on a more serious quality and became a performance. He took pictures on his phone. He recorded video footage. He wrote a blog post about it the next day. When a pedestrian walking in the opposite direction passed him and kicked the ice back toward Sam, this interaction became part of the performance, too. What was it that made my friend’s playful action into art? It seems, quite simply, his quality of attention and focus, and this documentation.

In one sense, writing isn’t very different. Writers sit habitually before their keyboards (or with a pen and paper at the ready), and in doing this attempt to isolate moments from life and reframe them on the page. Another way of understanding the performative in the literary is through John Cage, who said that literature, “if it is understood as printed material, has the characteristic of objects in space, but, understood as a performance, it takes on the aspects of processes in time.” The blurring of time and space, and of art and life, are central to Cage’s conception of art, that “art should not be different [from] life but an action within life.” An action as habitual as brushing your teeth can become art if a certain conscious attention is paid to it. Alan Kaprow, Fluxus member behind the Happenings, made a point to say that an artist’s renewed awareness of performing a repetitive action can reinvigorate this action, that “Ordinary life performed as art/not art can change the everyday with metaphoric power.”

This blurring of art and life by turning the everyday into art is an idea central to Barbara Browning’s latest novel, I’m Trying to Reach You. The novel borrows its title from the working title of a book that the narrator, dancer-turned-academic Gray Adams, is writing from his dissertation, during a post-doc year in NYU’s department of Performance Studies. Gray is never not researching. He’s always observing, texting, photographing, and scouring the Internet for material, especially YouTube, his “first resort in dealing with questions from the answerable to the unfathomable.” In these preoccupations, he ends up far more focused on novel writing than fulfilling his academic obligations, and as a result he leans heavily on this fiction to generate his academic work.

For an academic who comes to performance through what he calls “the more literal and slightly less fashionable side of the spectrum” of performance dance, Gray is a virtuoso at dissolving boundaries and conflating art and life. His novel largely borrows from his life. He begins writing in the summer of 2009, when he is in Zagreb attending an international performance conference on the day that Michael Jackson dies. Jackson’s death fuels Gray’s first line, “I was in Zagreb the day Michael Jackson died,” and from this the rest of the novel unfurls. Jackson’s demise is significant not only because of its untimeliness, but also because his death marks the first of three innovative dancers. Pina Bausch and Merce Cunningham follow in a matter of weeks, and this has Gray turning to YouTube for answers regarding the cryptic cosmic meaning contained within the coincidence.

It’s through his YouTube investigation that Gray discovers the mysterious and captivating videos of a dancer, posted by falserebelmoth. Gray is accustomed to reading messages into contemporary dance – his dissertation focused on semaphore mime in contemporary ballet choreography – and he reads into falserebelmoth’s dance, too, which includes a brief moonwalk homage to MJ. Gray observes that the dancer’s “gestures become more idiosyncratic and mysterious, as though she were trying to communicate some information.” Subsequent videos are posted with each death, and Gray lurks in an attempt to decipher their hidden meaning, viewing each video multiple times and scouring the comment thread. Gray’s desire to uncover a message, coupled with his multiple, seemingly related run-ins with a Jimmy Stewart lookalike, keeps him curious and on his toes. It also provides him with an abundance of material for his novel.

Browning integrates social media and contemporary modes of communication within the text as if it were second nature. Culturally we’re so constantly immersed in multiple layers of media – text messaging, emailing, chatting, posting photos and videos, and yet so few books actually convey this fluency with digital media (as was noted in a recent Millions essay, on the role of technology in fiction). But Browning pulls this off seamlessly. Images and video stills are integrated within the text. A picture of prized heirloom tomatoes snagged from a farmers market is snapped for later posting on Facebook; there are fruitless, patience-trying digressions within comments sections; text messages are volleyed back and forth across the Atlantic between Gray and his Swedish boyfriend; and Gray is always taking photos – to document the everyday, to research, to examine, to immortalize. Such is the case with the picture Gray takes of a man riding a stationary bike on his patio across the courtyard (also a nod to Hitchcock’s Rear Window). He reflects:

Documenting the guy across the courtyard was a way of gathering information for the book I might write. A kind of research. But after I’d taken the picture, I felt a little creepy. I made myself nervous wondering if anybody on the other side had noticed me taking the picture, and if they might have taken a picture of me taking a picture of the guy on a stationary bike.

This kind of lurking, in life and online, is something Gray touches on during his final academic talk of the year. He borrows heavily from Lauren Berlant (whose essay he found last-minute via Google search) when he says that we are increasingly “overheard and understated.” Gray is constantly listening in and observing others, whether they’re across the courtyard or leaving coded commentary, to fuel research for his novel, his academic papers, his performances. They are one in the same.

Life material becomes novel material, both for Gray Adams, and for Barbara Browning. Browning, too, was in Zagreb attending the very same conference on the day that Michael Jackson died. Browning, like her narrator, is an academic who teaches at the same university, in the department of Performance Studies. It’s significant to note that Browning refers to I’m Trying to Reach You, “not [as] a novel but a multimedia project linked to a series of chamber choreographies.” New digital media figures centrally within I’m Trying to Reach You; it provides the framework for Gray’s existence, as a tool for communication, for finding and archiving information, for documenting, for seeking solace while searching for an answer he has yet to find. But it dually becomes a medium for obfuscation, for misreading, for unleashing a labyrinth of potential meanings and inferences that may or may not exist.

Images of the twelve “chamber choreographies” that Gray watches are printed within the text. The videos are also posted for the reader to view on YouTube. In these videos, Browning is falserebelmoth, the dancer that Gray is watching. And so, if Gray Adams is Browning’s doppelganger, then falserebelmoth is another incarnation of the author, too, and through Gray’s gaze, she’s watching herself. By viewing Browning’s intimate dance performances, which take place in domestic quarters, we readers are made even more keenly aware of Browning’s multiple performances, the way that she parlays life into her art, and that every aspect of this novel constitutes an element of Browning’s performance. This fittingly is in line with Merce Cunningham’s emphasis of “each element in the spectacle.” And all the while, we readers are lurking and overhearing, watching Gray who is watching others, following Gray to YouTube, watching Browning as falserebelmoth dance in a bathtub. And by doing so, we are made newly aware of our own constant lurking, within the book and within our own lives too. - Anne K. Yoder

The novel’s great first sentence immediately sets the scene and introduces one of its preoccupations: “I was in Zagreb the day that Michael Jackson died.” (Had the novel been set just a year later, the protagonist, Gray Adams, could easily have been introduced as one of the many reperformers to appear in Ms. Abramovic’s MoMA show, lying naked and still beneath a skeleton for hours.) A former ballet dancer trying to come to terms with his post-stage life, Gray is now a graduate student in performance studies transitioning to a teaching career. On this fateful day, he’s at a fittingly obscure conference in Croatia. Its theme: “Misperformance: Misfiring, Misfitting, Misreading.”

Gray spends most of the novel texting loving emoticons to his boyfriend in Stockholm, listening to Satie on the StairMaster, and procrastinating while trying to turn his dissertation into a book. The dissertation’s title: Semaphoric Mime From the Ballet Blanc to William Forsythe: A Derridean Analysis, or, I’m Trying to Reach You.

It’s this procrastination that leads him to YouTube and the discovery of a series of dances by a mystery choreographer who goes by the handle falserebelmoth, setting off an absurdly fun conspiracy linking the deaths of major figures of the cultural world from 2009—Michael Jackson, Pina Bausch, Merce Cunningham, and Les Paul. A sinister figure named James Stewart who looks like James Stewart gets involved, too. Gray’s paranoid (or is it?) compulsion to connect them all loosely drives the book.

Browning calls the whole enterprise not a novel but a multimedia project linked to a series of chamber choreographies. All 12 of “the moth’s” dance videos are available on YouTube and star the author with the occasional guest. (The fact that the videos themselves can’t be fully integrated into the text makes I’m Trying to Reach You the rare instance where a digital version of the book might really be better than print.) But what Browning does with the YouTube dances themselves is truly inventive. The choreography ranges from balletic to samba to a seemingly drug-fueled spastic freak-out, with music from Satie to Carole King. For the most part, they’re entrancing. Describing dance is never easy, but Browning makes these miniworks vivid. The first, a response to M.J.:

The mudra-like hand gestures (“okay”), which morphed into antlers, and then something like a map of her ovaries; a little Charlie Chaplin walk, ending with a swat at her ankles; a delicate circling of her index finger over her head, as though it were a phonographic needle sounding the clunky little score. And then I saw it: looking down at her feet, she swiveled to the side, and discreetly moonwalked backwards across the floor.

It definitely wasn’t virtuosic, but it did have a hint of the uncanny, as the moonwalk inevitably does.

Browning plays with form and language in other ways too. Commenters on the videos become players in the plot—their responses are cribbed from Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. Browning used the Internet Anagram Server to construct her characters’ monikers, and suggests that readers use the site to retrace her steps. You may feel that this interactive sleuthing is more effort than necessary, but it’s hard not to admire her enthusiasm.

“Even when a dance appeared to be relaying a very clear message,” Gray says, “it was always already saying something altogether different.” On the surface they are quick, slightly shabby, DIY experiments: The moth poses in a bathtub; the moth and another woman, who sits on a chair, raise their arms in straight lines up and down. But watching them closely you see how each one enables Browning to tease apart aspects of performance and the major artists who shaped the form, making the novel and its accompanying choreography a sort of short history of modern dance.

One spurs a comparison to Merce Cunningham’s Septet: “They both featured Satie compositions, and, if anybody at YouTube actually cared about such things, they displayed a certain similarity in spirit, if not precisely in choreographic style. Merce’s, admittedly, was more technically refined. … What the moth lacked in technique, I felt she made up for in straightforwardness.” The commenters’ reactions to the dances also serve as a microcosm for an audience, and here Browning plays with ideas about perception, race, sexuality, and gender—all topics with which the performance world is in constant conversation, or battle.

Gray’s obsession with the moth’s videos also allows the novel to dive deep into the dance and performance art world, of which Ms. Browning—a member of the faculty in the department of performance studies at the Tisch School of the Arts—has a smart and clear grasp. Above all else, I’m Trying to Reach You serves as a snapshot of a certain slice of New York high culture at this particular moment. Even without the back-cover blurbs from Karen Finley and Vaginal Crème Davis, Browning shows her cred, dropping all the right references, from Ann Liv Young to Yvonne Rainer, flash mobs to Performa. (Let’s leave aside her sometimes daffy bits of gossip about critics, some of whom I, er, work with.) It’s clear she recognizes the often hilarious self-seriousness that pervades this world. (Another conference paper: “Peter Sellars: Snake-Oil Salesman or Enfant Terrible?”)

Browning’s fully-drawn characters, particularly Gray, are the constant that keeps this occasionally ridiculous book engaging. Gray is a sweet lost soul, whose dependence on the Internet and its power to feed this obsession offers a powerful commentary on the isolating effects of the Web. His need to get lost—whether in old Merce clips or in just Googling the “politics of lurking”—serves as a cautionary tale on the dangers of an always-mediated online life. And the people that surround Gray—his sick boyfriend, his fellow academics, his elderly neighbor and friends, even the commenters—are all confronted with loneliness too. Through them (and though, of course, M.J., Pina, Merce, and Les), Browning writes—sometimes movingly and subtly, sometimes clumsily and outrageously—about illness, loss, and death.

The often silly murder-conspiracy plot really isn’t what makes this book special. What Browning does with the form is genuinely creative and feels rightly reflective of a moment when dance is pushing the boundaries of what constitutes a performance space. Now that more and more mainstream museums are presenting choreographers—Sarah Michelson took over the fourth floor of the Whitney for its 2012 Biennial—why shouldn’t a book be a home for dance too?

After all, Gray’s YouTube habit may reveal his loneliness, but Browning’s book also makes clear what a treasure trove the Internet is for fans of dance, who can view performances once thought lost forever with the click of a mouse. I’m Trying to Reach You is a fun and dishy read for those fans—and also a daring and deep exploration of performance and the way it collides with, and is enriched by, the Web. - Julie Bloom

When Gray Adams, former ballet dancer turned academic, gets stuck turning his dissertation into a book, he does what any good academic does: more research. Unfortunately, his research isn’t into his book’s topic (“Semaphoric Mime from the Ballet Blanc to William Forsythe: A Derridean Analysis”), but rather into the deaths of three iconic figures in dance—Michael Jackson, Pina Bausch, and Merce Cunningham.

Browning’s playful novel follows Gray as he deciphers cryptic clues embedded in a series of YouTube videos. But readers expecting a mystery similar to Someone Is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe might be disappointed; even Gray realizes that his theories are probably paranoid projections. Instead, the novel delves into Gray’s scattered mind as he goes in search of information. Sometimes, Gray’s search leads him on surprising discoveries, such as when he uncovers the Swedish word for “boyfriend” (pojkvan, a compound word combining ‘boy’ and ‘skilled’).

At other times, though, he simply rambles. Gray occasionally disappears down a black hole of YouTube comments, uncovering vaguely threatening messages from a man he dubs “Jimmy Stewart,” as well as the original poster’s responses. But the comments speak at cross-purposes. Their “conversation,” comprised of quotations attributed to the “real” Jimmy Stewart and poetic fragments from Emily Dickenson, offers juxtaposition but no real discourse. (The less said about the sophomoric and homophobic responses from “real people,” the better.)

This, perhaps, is intentional. Browning’s novel is a pastiche. She cuts and pastes from many different sources to create a multimedia experience. (The videos that Gray sees, for instance, are available on YouTube.) And while this works, Browning often fails to exploit how different media can work together. For example, when Gray sends photo messages to his Swedish boyfriend, Sven, Browning includes the photograph in the text. But rather than parse the photograph or use the photograph as a jumping-off point for further musing (a là W. G. Sebald), Browning merely describes what’s in the picture, as if seeing it weren’t enough. Similarly, Browning includes lengthy summaries of the film noirs that Gray and Sven see, but doesn’t examine how these films illuminate their relationship. The summaries add texture but no flavor.

Indeed, the characters, other than Gray, feel nebulous. Gray exists so much in his own head that the other people who pass through his life do exactly that: pass through. His involvement with Sven consists mostly of text messages and emoticons. They act less like boyfriends and more like FWBs (Friends With Blackberrys). Sven’s HIV-positive serostatus is given less space than, say, a hermeneutic examination into Les Paul. But, even though Browning isn’t aiming for psychological realism—indeed, Gray continually claims that he is short on cash, but never has any issue jetting off to Europe—she prefers to play for bemused chuckles, like Gray’s deaf downstairs neighbor, described only as “Bugs Bunny’s sister,” who speaks IN ALL CAPS WITH AN EGGZAJURATED NOO YAWK ACCENT.

Despite its flaws, the novel shows ambitious scope, encompassing everything from critical theory to the relationship between Merce Cunningham and John Cage. But, in the end, the novel feels like watching an artist’s greatest hits on YouTube: you get all the high points, but it doesn’t feel like an album. - Viet Dinh

Barbara Browning has also published an audionovel (Who Is Mr. Waxman?) and two academic books (Samba and Infectious Rhythm). She has a PhD in comparative literature from Yale University and teaches in the Department of Performance Studies at the Tisch School of the Arts, NYU. She’s also a poet, a dancer, and an amateur ukuleleist

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.