Jeremy Fernando, Writing Death, with an introduction by Avital Ronell. The Hague: Uitgeverij, 2011.

jeremyfernando.com/

Writing Death opens a meditation on the possibility of mourning; of whether there is a subject, or even object, that one mourns--of whether one is mourning, can only mourn, the very impossibility of mourning itself. The manuscript is framed by two attempts at mourning--Avital Ronell's "The Tactlessness of an Unending Fadeout" and Jeremy Fernando's "adieu." In-between--for this is where both pieces posit the possibility of attending to the passing, the memory, the fading of the person--is an attempt to think this impossibility. The text is continually haunted by the question of whether one is mourning the person as such, or a particular version of the person, a reading of the person. And in reading another, in attempting to respond to the other, one can never have the metaphysical comfort that one is reading accurately, correctly; in fact, one may always already be re-writing the person. Thus, all one can do is attempt to mourn the name of that person, whilst never being certain of whether her name even refers to her any longer.

All one can do is write death.

"Ask not for whom the bell tolls... Eulogy: one of the many English words combining legein (to gather together) and logos (the word, the law). With eulogy though the speech-act itself is all important (eu-) and its impossibility evident in a written work. The site of the gathering together of words, of scattered sounds, disappears in the act of writing, itself scatter--all too forcefully underlining the cause, the event of dispersion that creates the need for gathering together. Jeremy Fernando's eulogy, this particular eulogy, is called Writing Death, and it reminds us that eulogy in its impossibility may well be the primary genre of writing. Writing and death have always gone together, hence Plato's suspicions of chirographic technologies. The author is absent, as is the subject. The text brooks no questions and gives no answers. Fernando's gathering of scatterings in the form of mini-meditations unfolds the weaving of textus that makes writing possible and makes death comprehensible in all of its paradoxical mystery and awe-ful presence. His is a book of catalysts: use them with care."--Ryan Bishop

Rite and ceremony as well as legend bound

the living and the dead in a common partnership. They were esthetic but

they were more than esthetic. The rites of mourning expressed more than

grief; the war and harvest dance were more than a gathering of energy

for tasks to be performed; magic was more than a way of commanding

forces of nature to do the bidding of man; feasts were more than a

satisfaction of hunger. Each of these communal modes of activity united

the practical, the social, and the educative in an integrated whole

having esthetic form.(1)

Jeremy Fernando’s Writing Death

is a sensitive attempt at exploring the depths and heights to which the

processes of mourning can take us. Death, as an absence, renders all

gestures (for what is mourning but a gesture with many faces)

surrounding it at once as a possibility and an impossibility. Fernando

poses questions that often elude the mourner and the mourned—the same,

and different—by raising the specter of subject and object; by

compelling the examination of what it actually means to mourn; and most

crucially, by considering the very status of possibility itself that the

act of mourning foregrounds.Mourning, he reminds us, is premised upon memory (remembrance, recollection), the shadow of forgetting upon which is perpetually cast—the inextricability between memory and forgetting haunts the living more than it does the dead. And if grief has anything to do with it, mourning can quite easily be mistaken for an attempt to remember in order to forget; an attempt, in other words, to deny death, deny the one thing that confirms mortality. As if living has anything to do with it.

What, then, of writing death? It becomes an unceasing process of locating—and addressing—possibility itself: the passing as possibility; loss as possibility; impossibility as, and of, naming this possibility. In confronting the passing on, it is possible, nay inevitable, to move on, move away from the site of loss, of grief. All the while, we forget, Fernando reminds us, that mourning has little to do with the dead, and a whole lot to do with the living, the mourning self. Here, he echoes Dewey’s consolidation of rituals and ceremonies, of the dead and of the living, all as parts of a larger unity, of a social, public gesture meant to sate a private need:

In trying to “get over it,” are we trying to get over ourselves? Or more than that: are we trying to get over the fact that we can never quite get over ourselves? (Fernando, 77)

As if guilt has anything to do with it. And “it” continues to be the point that he is driving at, driving towards. “It” is the possibility and impossibility, death and life, memory and forgetting, lost and cherished. “It” is what eludes mourning, eludes attempts to overcome grief.

Nonetheless, move on, he must. And Fernando does this in fewer moves than a 12-step program—hardly therapeutic, but intellectually satisfying. Writing Death attends to some of the pertinent aspects of the act of mourning—both as gesture and as meditation: eulogy, distress (call), tears, and the question of how (beyond ritual, beyond sentimentality) to mourn. And what’s love got to do with it? Everything and nothing. Mourning, after all, is an articulation of love, but it is also one that forces the mourner to be selective, as with myth-making, in the recollection:

Remembering only ever occurs in exception to memory—quite possibly in betrayal of a memory. In this way, each remembrance is a naming of that memory, a naming of something as memory, bringing with it an act of violence. (40)

Mourning is thus not only an act of fictionalizing, it is also an act of reading, to continually be compelled to respond to another, all the while keeping vigil against a reconceptualization of the dead, without, therefore, misreading the dead. This can only be done, Fernando argues, by all the while “maintaining the otherness of the other. After all, one must try not to forget that one cannot be too close—space is needed—to touch.” (82) There is also tacit acknowledgement that doing so foregrounds the fact that the selectivity of memory becomes exclusive, and concretizes into a singularity, thus negating the multi-dimensionality of a life lived – and thus killing the already dead.

Writing Death is framed by two eulogies—or the approximations of eulogies; approximation because both foreground and call into question the eulogy as a genre. The first is Avital Ronell’s foreword to the book, remembering Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe; the second is Fernando’s own response to the passing of a mentor, Jean Baudrillard. Both are not merely attempts to philosophize their way out of the act of mourning. Both are in fact deeply moving pieces that remind us of the emotional possibilities that may reside within any intellectual undertaking, that the latter need not be cold and devoid of feelings. And whereas Writing Death does not attempt to make any philosophical claim for humanism, the underlying wistfulness of both pieces does suggest that there is a proper place for deep-seated human response to death. We can (and the book does) intellectualize and problematize the acts of mourning and grieving, but these do not diminish the fact that we mourn and grieve. And, framing Writing Death as the two eulogies do, Jeremy Fernando perhaps finally, and inadvertently, names “It”—it is, above everything else, Human. - Lim Lee Ching

Walter Mason interviews Jeremy Fernando

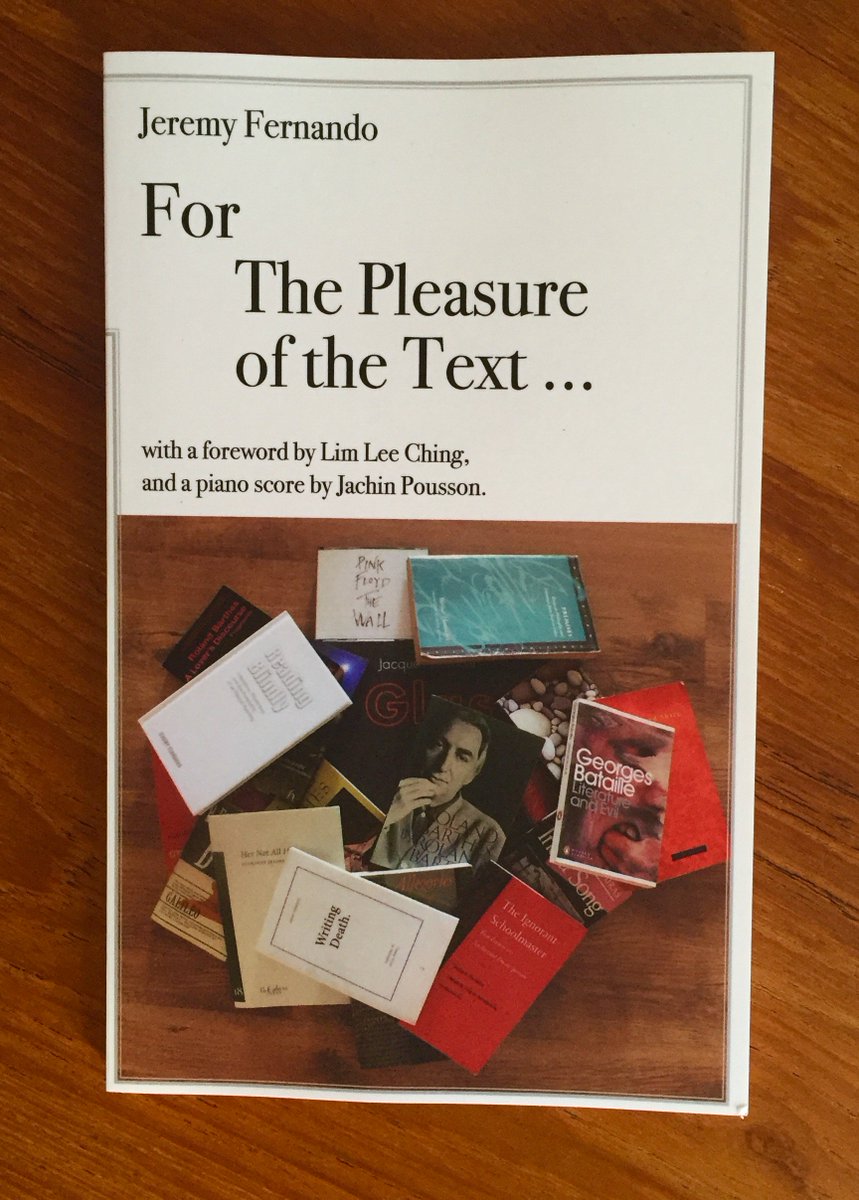

Jeremy Fernando, For The Pleasure of The Text, Delere Press, 2015.

At the heart of this book lies attempts to read: reading here being understood as the openness to the possibility of another; a relation that occurs prior to any semantic or formal identification, and, therefore, prior to any attempt at assimilating, or appropriating, what is being read to the one who reads.

Thus, an event.

It opens with Lim Lee Ching's reading of this book; a reading before your reading, as it were. And is followed by Jeremy Fernando's attempts to respond to the many Roland Barthes -- all whilst foregrounding the risk that, even as one attempts to read as openness to the possibility of another, all reading potentially re-writes the other; that his reading may well be an inscribing of his R.B.; that whilst reading it, you may well be making your very own R.B.. In the midst of which, you will find a piano score composed by Jachin Pousson: which is both a nod to the fact that Barthes was a pianist, and also a note to the musicality of the thought of Roland Barthes.

Thus, an event.

It opens with Lim Lee Ching's reading of this book; a reading before your reading, as it were. And is followed by Jeremy Fernando's attempts to respond to the many Roland Barthes -- all whilst foregrounding the risk that, even as one attempts to read as openness to the possibility of another, all reading potentially re-writes the other; that his reading may well be an inscribing of his R.B.; that whilst reading it, you may well be making your very own R.B.. In the midst of which, you will find a piano score composed by Jachin Pousson: which is both a nod to the fact that Barthes was a pianist, and also a note to the musicality of the thought of Roland Barthes.

The hope is that these readings bring, open the possibility of, pleasure: not just for the one who reads, but perhaps even for -- if one allows oneself to imagine -- the text. For the one we call, name -- can do nothing but name -- Roland Barthes

Books

Jeremy Fernando & Julian Gough. an apple a day ... , with an introduction by Neil Murphy, and photography by Tan Jingliang. Singapore: Delere Press, forthcoming.

Jeremy Fernando, Jennifer Hope Davy & Julia Hölzl. [Given, If, Then]: a reading in three parts. New York: Punctum Books, 2014.

Joyous in the exploration of reading’s impossibilities and the mystery of being exposed, there, before the unknown.

-Christopher Fynsk

[Given, If, Then] attempts to conceive a possibility of reading, through a set of readings: reading being understood as the relation to an Other that occurs prior to any semantic or formal identification, and, therefore, prior to any attempt at assimilating, or appropriating, what is being read to the one who reads. As such, it is an encounter with an indeterminable Other, an Other who is other than other — an unconditional relation, and thus a relation to no fixed object of relation.

The first reading by Jeremy Fernando, “Blind Reading,” unfolds through an attempt to speak of reading as an event. Untheorisable in itself, it is a positing of reading as reading, through reading, where texts are read as a test site for reading itself. As such, it is a meditation on the finitude and exteriority in literature, philosophy, and knowledge; where blindness is both the condition and limit of reading itself. Folded into, or in between, this (re)reading are a selection of photographs from Jennifer Hope Davy’s image archive. They are on the one hand simply a selection of ‘impartial pictures’ taken, and on the other hand that which allow for something singular and, therefore, always other to dis/appear — crossing that borderless realm between ‘some’ and ‘some-thing.’ Eventually, there is a writing on images on writings by Julia Hölzl. A responding to the impossible response, a re-iteration, a re-reading of what could not have been written, a re-writing of what could not have been read; these poems, if one were to name them such, name them as such, answer (to) the impossibility of answering: answer to no call.

Jennifer Hope Davy is an artist and writer whose work moves between the poetic and the parodic, largely operating in the form of a gesture, an act or a proposition. She was born and raised primarily in Jersey (New Jersey). She has studied, worked and wandered in various countries across the globe and is now currently in situ. Davy received her Fine Arts degree from the San Francisco Art Institute, her Masters in Art History and Criticism from the University of Texas San Antonio and completed her PhD at the European Graduate School (EGS), where she is currently a post-doctoral fellow, focusing on contemporary art as an apparatus of mobility within aporetic junctures. Forthcoming books include Staging Aporetic Potential and Pedestrian Stories. In addition to art and writing, Davy has functioned as a critic, curator, editor, producer, and professor of art and media studies.

Jeremy Fernando, On fidelity; or, will you still love me tomorrow, Atropos Press, 2014.

This text attempts to open the dossier of fidelity; and, in particular, attend to the question of the relationality between fidelity and its object, to the question of must there be an object to fidelity? For, if one is faithful to something or someone, is one responding to the what, the characteristics of the thing, the person; or the who, the person, thing, as such? Which is not to say that what and who are necessarily distinguishable, separable, to begin with. However, if we open the register that the who is always already beyond us -- outside of knowability, even if only slightly -- this suggests that it is the spectre, the potentially unknowable, that haunts all relationality. Thus, even if there is an object to one's fidelity -- without which one cannot even begin to speak of fidelity, speak of relationality -- this might well be an objectless object or, at least, an object that remains veiled from us.

Jeremy Fernando, Living with art, with illustrations by Yanyun Chen. Singapore: Knuckles & Notch with Delere Press, 2014.

Jeremy Fernando, On Invisibility; or, towards a minor jiu-jitsu, illustrated by Yanyun Chen. Singapore: Delere Press, 2013.

On Invisibility attempts to meditate on the relationality between the seen and unseen, known and unknowable, particularly when in relation with an other, when grappling - in touch with - another. This text opens the dossier that, whilst seemingly antonyms, invisibility is part of visibility; that each act of seeing is fraught with the possibility of blindness. And more than that, relationality with another is premised on this very unknowability. Which is why, not only does one encounter jiu-jitsu through practice, praxis; not only does one encounter jiu-jitsu through an encounter with the other; part of it always escapes us, remains enigmatic. Thus, not only is it arte suave, it is always also potentially arte bela. So, even as we attempt to address the question what is jiu-jitsu, part of it will always remain beyond us. Which might be why we have no choice but to turn to art: for, all that we know, can see, of jiu-jitsu will be fragments of it - sketches.

"On invisibility is a remarkably elegant but also daring and truly thought-provoking work. What it dares and also asks the reader to dare is to reconsider and rethink not only how to understand jiu-jitsu, its different teachings, schools and methods as such, but also - and no less importantly - to question the very basis of what seeing, understanding, thinking and knowledge here means. The very possibility of questioning anew, of opening the imagination to other possibilities is in Fernando´s work intimately linked to the relation between the visible and the invisible, the known and the unknowable. These apparent antonyms delineate in On invisibility no longer a simple and stable border between what can be thought and what must remain outside thinking. Rather it would seem that jiu-jitsu in Fernando´s beautiful writing - both as a praxis and indeed as art - thoroughly destabilizes and transgresses what we usually attempt to separate and thereby confronts us with a blindness of seeing - a darkness in the midst of sight - and a non-thought of thought. Beyond oppositions, beyond what can be taught, controlled and repeated there is the moment of discovery and of experience, a "flow with the go" which is so uniquely singular that it seems to approach something universal. Thanks to the dynamics between the book´s text and illustrations, between Fernando´s writing and Chen´s graceful drawings, the work itself has all the seductive force of the jiu-jitsu masters that the work describes." - Anders Kølle

Jeremy Fernando, Kenny Png & Yanyun Chen. Requiem for the Factory. Singapore: Delere Press, 2012.

Requiem for the Factory is a conversation between two forms of writing: language, and light. This occurs in a tale that attempts to explore the relationality of a self to her self through the figure of a factory. Told through an "I" that refuses to remain stable, one is never sure whether this is a moment when the tale is recounted, recalled, or whether it is being told at the moment of telling. And this is why this requiem has to be narrated. What is foregrounded is not only the fact that memory, history, is fictional, but more pertinently that the self-and the "I"-can only be uttered, perhaps even known, through fictionality. This is not to say that the self is imagined-unreal-but that the imaginary is in the very fabric of reality itself. This is a tale of two writings that are speaking to, and with, each other, whilst also speaking in their own realms at the very same time.

Jeremy Fernando, The Suicide Bomber; and her gift of death. Atropos Press, 2010.

This book is an attempt to defend the undefendable: the suicide bomber as a figure of thinking, a figure that foregrounds the singularity of each event; and it is this un-understandability-which is part of understanding itself-that the suicide bomber never lets us forget. For, the suicide bomber is the poet par excellence, reminding us of the possibility of an event; not because of the effects of her actions, but due to the gift of her life, and more importantly the unknowability that is her death. And like with poetry, all analysis only makes it worse. In this manner, (s)he remains an unending question for us; a question that even questions itself as a question. And if one maintains the question, one is always already other to everything, other even to one's self. In this way, the gap between the self and the other is maintained such that this space is never taken hostage. For, the moment this space of negotiation is gone, we are in the realm of terror."Jeremy Fernando's The Suicide-Bomber; and her gift of death calls for the ability to respond to intentional death. It is a brilliant study about the blank spot within the becoming of teleology, and the game of 'finitude'." -- Hubertus von Amelunxen

Do not judge a book by its cover! However, what covers a book if not a title? Thus, by virtue of its appellation The Suicide Bomber; and her gift of death, recently published by Atropos Press, promises much by calling judgment right to the front of thinking. Yet this work goes deeper than mere provocation. Fernando appeals to configurations of the suicide bomber not by the final judgment, nor the terrorist per se, rather, a gift of death by its pedagogical task one is called to engage within and without the limits of judgment and reason.

Fernando defines terror as the attempt to “efface” the site, “the illusion…the medium between reality and ourselves…the space, the gap of negotiation.” The gift of death is thus a work of confusio against ordo, that is, the aporia between persons (if only between one-self) and the access to uncertainty taken for granted in late capitalism. Working primarily with Jean Baudrillard and in other instances the mystical humidity of sex-death master Georges Bataille, Fernando works toward a novel “exchangeability” previously dominated by Christian and capitalistic frameworks now taken to the limit of limits. A work between order and chaos moves toward a possible, novel-self, “when she straps the bombs to herself, she is already dead,” that is, already effaced by terror, thus reason is indeed terroristic. Preconceptions of the gift-bringer are ultimately shaded into ideological structure, our own ‘self’, thus a motif on self referentiality occurs toward this novelty of I, yet further discussions of technologically influenced subjectivity do not appear.

Any attempt to psychoanalyze the actor is indeed assigning meaning where there isn’t one. In terms of effacement, nationalistic definitions contra the terrorist use terrorism as that which fundamentally reshapes the nation as a whole. The possibility of meaning is already effaced by the assigned rationale of terrorism which squares with Fernando’s primary thesis. Thus the nation-state and its media apparatti and the implementation of terrorism is turned on its head. (161) For example, the highly politicized suicide bomber post 9/11 was termed by right wing Fox News as the “homicide bomber” (Fox made the appeal to be factual and pro-American, taking the emphasis away from the suicide to a murderer.) The “homicide bomber” in such depiction is purely other, knowable by their intention to kill others, not by the fact they started with themselves, i.e. “already dead.” Thus Fernando’s work does have a political impetus. And certainly the reason one kills is not an easy configuration, yet a commentary on the limits of knowing exchanges between a supposed bipolar world and the subject appears to emerge.

The bomber opens the possibility of exchange thus the trans-gendered conceptualization nearest this site of negotiation: “Every time a suicide bomber offers her-self, she is offering us the possibility of singularity, the possibility of remaining unknowable, enigmatic, and in full potential. At the instant she becomes a suicide bomber, (s)he offers us the gift of her death: we reciprocate, we return the gift, with our lives.” (185) This exchange operates by opening binaries, such as the of fixity of gender which has dominated biology. In this exchange, biology reinscribes gender, proximate to the gift, which can be also be read as an event “we are always stricken with death…a death from within that remains unknowable” (16) for which the bomber brings forth in us, immanent to ourselves. The delivery of a complex reworking of gender is indeed deceptively easy to breeze through, but it openly obscures its actual close-reading of identity and gender whispering forth.

The gift is the non-anthropocentric blip of poesy, or blast-error within all truths. The flesh pelted marketplace of ideas means the bomber is the non-actualized poet among us, actualizing if only for a moment. The task is to understand this ourselves. In the vibrancies of living the gift is an appeal to live. How Fernando establishes this novel self comes by the complex phrasing of “an ‘I’ that is in alterity with itself; a self that is other to itself…[a]nd this is the position of being other to one’s self that we may find some hope” leaves a more decisive conclusion for another day. (215) In its moment and its event, the expanse of a possible terrain of becoming we are tasked with: the uncertainty of understandingand welcoming the other. Terrorized by reason masking uncertainty, the explosions of poetry in a life we have yet to see, means sight takes much for granted which pulls forth an intuitive read on Levinisian ethical optics. Happening all around us poetry as the exploding gift repulses common sense only to establish a new possible ground. Other in this sense is the symmetrical alignment for the murder, the final judgment surpassed, which in the operation of other and self have no further distinguishing elements. We may only meet each other in oblivion. This new self is not one who grasps the mini-sun, the bomb, who pulls the trigger and destroys the marketplace, it is poetry, the pure, open negotiation.

Though we can read a grasping of technology in the bomb the residue of design in this case is not a luck we can properly judge nor a proper subject of the future, rather, the non position of “perhaps” of both Friedrich Nietzsche and Jacques Derrida who reign supreme in this text. The explosion could speak more about the artist’s impact on the structure of society as purely a production of negation either emerging or shrinking back from the atomic age and apocalyptical thematics.

Fernando does offer a bridge in this text between politics and philosophy, that is, a meditation of “I” in contrast to the split androgyne featured in one of the more successful vignettes. Tracing back the bifurcated one and third position of the body (less we read it politically or sympathetically,) we gain a moment to understand life at its limit, reaching toward living. How one understands the suicide bomber requires meditation on the validity of the subject in relation to technologies, its models in late capitalism long dominated by outmoded post-colonial studies and the programmatic identity politics of diversity. The question emerges: Could we finally abandon the dogmatic fixity of political identity as merely individual?

A work for every level of interested readers, Fernando’s uncommon ease with the often over-obfuscated tenants of continental thought make this work accessible and pleasurable. Stylistically this work employs several intimations or vignettes which act as a commentary on the work but in some instances feel as if missing the pressure they are supposed to invoke. This is done, however, with pristine clarity, which makes his conclusions vulnerable to criticism but also ripe for exchange, if not the same sort of exchange he critiques with acute skill. The question concerning style could be contrasted to the later Gilles Deleuze and Jean-Luc Nancy, there is a certain authority in the way in which a text is written. And for this reason, there are numerous instances where Fernando displays a developed and deep intuition of his subject matter, not as sheer indulgence, rather, a broad knowledge of literature and philosophy which is tactfully woven. One should read him carefully not on the terms of difficult language but for the subtle exchange he offers. - A. Staley Groves

Jeremy Fernando & Kenny Png, On Happiness. Singapore: Math Paper Press, 2010.

Jeremy Fernando, Reading Blindly: Literature, Otherness, and the Possibility of an Ethical Reading. Cambria Press, 2009.

Reading Blindly attempts to conceive of the possibility of an ethics of reading--"reading" being understood as the relation to an other that occurs prior to any semantic or formal identification, and therefore prior to any attempt at assimilating what is being read to the one who reads. Hence, "reading" can no longer be understood in the classical tradition of hermeneutics as a deciphering according to an established set of rules as this would only give a minimum of correspondence, or relation, between the reader, and what is read. In fact, "reading" can no longer be understood as an act, since an act by necessity would impose the rules of the reader upon the structure of what (s)he encounters; in other words the reader would impose herself upon the text. Since it is neither an act nor a rule-governed operation, "reading" needs to be thought as an event of an encounter with an other--and more precisely an other which is not the other as identified by the reader, but heterogeneous in relation to any identifying determination. Being an encounter with an undeterminable other--an other who is other than other--"reading" is hence an unconditional relation, a relation therefore to no fixed object of relation. Hence, "reading" can be claimed to be the ethical relation par excellence. Since "reading" is a pre-relational relationality, what the reader encounters, however, may only be encountered before any phenomenon: "reading" is hence a non-phenomenal event or even the event of the undoing of all phenomenality. This is a radical reconstitution of reading positing blindness as that which both allows reading to take place and is also its limit. As there is always an aspect of choice in reading--one has to choose to remain open to the possibility of the other-- Reading Blindly, by extension, is also a rethinking of ethics; constantly keeping in mind the impossibility of articulating an ethics which is not prescriptive. Hence, Reading Blindly is ultimately an attempt at the impossible: to speak of reading as an event. And since this is un-theorizable--lest it becomes a prescriptive theory-- Reading Blindly is the positing of reading as reading, through reading, where texts are read as a test site for reading itself. Ostensibly, Reading Blindly works at the intersections of literature and philosophy; and will interest readers who are concerned with either discipline. However as reading is re-constituted as a pre-relational relationality, it is also a re-thinking of communication itself--a rethinking of the space between; the medium in which all communication occurs--and by extension, the very possibility of communicating with each other, with another. As such, this work is, in the final gesture, a meditation on the finitude and exteriority in literature, philosophy--calling into question the very possibility of correspondence, and relationality--and hence knowledge itself. For all that can be posited is that reading first and foremost is an acknowledgement that the text is ultimately unknowable; where reading is positing, and which exposes itself to nothing--and is in fidelity to nothing--but the possibility of reading.

Jeremy Fernando, Reflections on (T)error. Saarbrucken: Verlag Dr Müller, 2008.

Terrorism is usually regarded as the enemy of globalization and capitalism. However this analysis completely misses the point as terrorism is precisely what allows globalization to exist: by ensuring that the fantasy of total exchangeability is never fulfilled, terrorism sustains the logic of capital itself. Reflections on (T)error is a meditation on the problems of confining the thinking of terrorism within the logic of exchange. This logic keeps us in the cycle of exchangeability: we remain within the game of surplus value and one-upsmanship; human lives are the very stake with which this game is played. It is only through looking at terror as such - as a singularity - that this cycle might be avoided; not by opposition nor by distancing oneself from it, but rather by complete immersion in terror itself. This book seeks to respond to the need to reconstitute the question of terrorism from a philosophical standpoint. It is addressed to researchers that think the realms of terrorism, post-structural philosophy and media philosophy.

Edited Books:

Jeremy Fernando (Ed.). On Reading; form, fictionality, friendship. New York: Atropos Press, 2012.

Jeremy Fernando & Sarah Brigid Hannis (Eds.). On Blinking. The Hague: Uitgeverij, 2012.

Articles:

If writing is of the order of death, and reading is the order of life — or a reviving, resuscitation, even necromancy — then the question that is opened is: what happens in-between? Or, perhaps more importantly, what happens to the text in that in-between state; where, when, it is neither alive nor dead? And as one attempts to bring the text from this death, does one — like Orpheus — have to just stare ahead as one reads: not look back lest the text fades away from us. Does one, can one only, read as an act of faith that something is coming along, that the text comes with us, from its grave?

Which opens the possibility that reading always also — if not already — entails a looking away, a turning of one’s gaze from, the very thing that one purports to be reading, attending to, responding with. Averting one’s eyes at the very moment of reading itself. Not only does this open the register of reading as a moment of re-writing, this writing might not even be of the order of repetition. And, even if it is a repetition — for one cannot write without repeating something, recalling a memory, harking language itself — it might well be a repetition of something completely other, of a completely different order, a repetition that depletes the memory of what it is purporting to recall.

Perhaps here, in this moment of darkness about reading, what comes to light is the adage that reading improves one’s imagination. And here, one should never forget that to imagine something requires a certain correspondence; it has to be based on something previously known — in this case, language itself. Language that is based on other readings, other texts that one has read. Thus, there is a possibility that at the moment of reading — a moment that might always already remain shrouded from one; which suggests that one might not know if one is reading, let alone if one has read — all that one is reading is every other text that one has read, every text except the one that one is attempting to read.

Thus, what is being raised from the dead is not so much the text that one is attempting to attend to, but every other text that one has read: the text in front of one being the ritual through which reading takes place. But even as reading the text might be construed as a sacrifice that one passes through in order to read — not that we can fully comprehend what this even means — one should bear in mind Georges Bataille’s teaching that “sacrifice destroys that which it consecrates. [But] it does not have to destroy as fire does; only the tie that connected the offering to the world of profitable activity is severed, but this separation has the sense of a definitive consumption; the consecrated offering cannot be restored to the real order.” [1]

And what is “severed” is precisely the notion of reading as production, of gaining something from reading, of reading as “profitable activity.” In the attempt — for, it would not be a ritual if the end result was known, let alone guaranteed — to read, the text itself might well remain — after all, sacrifice “does not have to destroy as fire does” — but even as it remains, it “cannot be restored to the real order”; which suggests that the moment of reading introduces a cut, a caesura, between what is being read and the possibility of reading. Which means that, not only does one quite possibly not know if one has read, one might not even know if one is reading. For, if it is no longer of the “real order” it is not only uncalculable, unexchangeable, but also beyond the ratio, rationality, beyond reason itself; and thus, might well also be beyond comprehension.

But, it is not as if one is unaltered by reading: that would be — or at least is potentially always already — untrue. So, what is perhaps also cut, “severed”, “cannot be restored to the real order” is one’s self.

Thus, one might well be changed, just in ways that might well be — remain — beyond one.

However, in order to know that, one would have to attempt to read oneself.

/

The text that is being read maintains its otherness from the reader (who is central) when the reader maintains a certain blindness to it. In other words, it is only when the reader does not claim full knowledge over the text but is in continual negotiation with it that the text remains fully other. It is the space, the gap, between the reader and the text that is the site of reading, for it is this gap that ensures that “understanding is [always] in want of understanding”: the reader is responding to the text, whilst acknowledging that it is impossible to fully understand the text, all the while realizing that understanding itself brings with it a un-understandability … It is this gap, between understanding and un-understandability, this gap within understanding itself, that ensures that reading can even begin to take place.(Reading Blindly, 59)

Each writing, each inscription, is in some way in preparation for our absence: in future-memory of the eulogy that will be written for us—a call for that eulogy that is always already to come.(Writing Death, 59)

The centrality of the reader, the one who reads: without which, one is doing nothing but a disavowal of responsibility, a denial that it is one — and no other — that is reading the text, making claims on and of the text, enacting a certain violence on the text. Reading a text without recourse to — without turning to — the fiction of the one who has written it, the one whom is called, named as, author of the text.

Without turning to the gaze of authority.

Without asking: daddy, daddy, what is to be read?

Which also means that not only is reading an attempt to read in place of daddy — in the absence of daddy, perhaps even to exorcise daddy — in the re-writing, one might well be authoring daddy.

In the reading, one might well be doing nothing but anointing oneself daddy.

… in nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti …

But, even as one is doing so, this does not mean that one can fully exorcise the name that stands before one — the name of the author. The name that all attempts to read — even if reading is an attempt, one’s attempt, “at responding to the text, whilst acknowledging that it is impossible to fully understand the text, all the while realizing that understanding itself brings with it a un-understandability” — are not only haunted by, but linked to, if not premised upon. For, even as one separates the text from the writer, the text does not exist without first having been written. So, even as one’s reading of the text quite possibly happens independently of the one who writes it, the link cannot quite be completely severed. However, this is not a link that is based on intention — nothing quite so banal — but on the very notion that the text that is being read, the text that is being attended to, is the very same text that is written.

Perhaps, one might even go as far as to say: reading is the moment when the text itself is authored — by the one who reads — and what is inscribed is the very notion of reading itself. Never forgetting that writing, each moment of writing, is “in some way in preparation for our absence … a call for that eulogy that is always already to come.”

Thus, a calling for a text that is perhaps not quite there yet, but always already to come. A calling that never quite knows exactly what it is calling; a reading that never quite knows if it is even is reading.

For, in every inscription — every writing by way of reading, writing that is reading — every scribere, there is always also the notion of tearing, ripping, perhaps even a mourning for what is unwritten, for the unwriteable in what is written … written whilst tearing, with a small tear.

Blind reading.

Keeping in mind that, “this is not a blindness that is negative in the sense of a deliberate refusal to see certain readings, certain possibilities, a blindness that is opposed to sight, but rather a blindness that is inevitable, a blindness that is structural, beyond subjective choice. Not an I do not want to see, but that I cannot see …” (Reading Blindly, 144)

Keeping in mind that as one is reading — even as this reading is fraught with blindness — that as one is attempting to respond to a text, a text that one might be writing as one is reading, one is also naming this very text as a text one is reading, one is naming it as one’s text, even if that is a momentary naming. And at the moment of doing so, one is also inscribing the name of the author: this is why the author is dead — not because (s)he is not there, not because (s)he is missing, but that in attempting to read the text, one is always also writing her into being.

The author as the name for the moment, the site, even the possibility, of reading. Reading as writing the author; reading as a “call for that eulogy that is always already to come.”

Even if one is the alleged author.

/

It’s hard to say whether a book has been understood or misunderstood. Because, after all, perhaps the person who wrote the book is the one who misunderstood it…

(Michel Foucault)

For to understand, to claim to comprehend, is to seize, to grasp, to subsume a book under one, under one’s self. It is to squeeze the life, the vitality, the movement, out of the text.

But it is not as if one can read without a gesture — no matter how temporary — of understanding. Even if, one heeds Werner Hamacher’s warning that, “understanding is in want of understanding,” that all understanding brings with it, is even premised on, un-understanding. [2] That perhaps understanding itself is nothing more than a useful heuristic fiction; without which, however, no reading itself would be possible.

Perhaps the only one who can resist this is the one who writes — not because (s)he is the one against murder, but that (s)he has long already killed it; by writing it. [3]

Perhaps then, without this primordial murder, no act of writing would even be possible. Keeping in mind that what is being murdered is the text itself. Not that the text itself dies, not that the one who writes even has a remote chance of killing the text — after all, it only comes into being through writing; thus, could not otherwise be around to be killed — but that the attempted murder is the very ritual through which the possibility of writing is opened. Thus, perhaps what is killed is none other than the one who writes, the self who is attempting to write.

Which is why writing is “a call for that eulogy that is always already to come”: for, it is nothing other than an attempted suicide.

Never forgetting — as Larry Rickels, channeling Freud, reminded me one summer in Saas Fee — that suicide is also an attempt at killing, murdering, the other.

And this is the true radicality of Roland Barthes’ claim that, “to know that one does not write for the other, to know that these things I am going to write will never cause me to be loved by the one I love (the other), to know that writing compensates for nothing, sublimates nothing, that it is precisely there where you are not — this is the beginning of writing.” [4] It is not just that one cannot write for another, for the other; it is not just that one attempts to write out of love for the unknowable, unreachable other, but that whenever one writes, one enacts a murder on the other — the other that is in one’s self; the other that is the one who first reads what one writes, that brings one’s writing into being through first reading it.

Not just that “this is the beginning of writing” but that in the beginning there was writing.

But not a writing of one, nor by an other, certainly not for another.

Just writing. - Jeremy Fernando. 'Reading Jeremy Fernando' in The Singapore Review of Books, 2014.

---. 'I had some dreams; or, Tan Chui Mui in my coffee ...' in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2014.

---. 'On relationships ...' in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2014.

[translated as ‘Hablando de Relaciones… El Amor por el Fútbol’ by Alvin Góngora in Orange Utan Lab, 2014]

---. 'An essay on what it is to be a leader' in Vice UK, 2013.

---. 'Playing with Putin; first as tragedy, then as ..." in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2013.

---. 'Lee Kuan Yew's death has already taken place' in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2013.

---. 'Sitting in the dock of the bay, watching ...' (Berit Soli-Holt, April Vannini, & Jeremy Fernando, Eds). in continent: A Quarterly Review of Culture (Special Issue --- drift), 2013.

---. 'On trinkets; or, this crazy little thing called love ...' in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2013.

---. 'Raging Bull, meet Running Bear' in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2012.

---. 'Enter the dragon---or, yes we can' in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2012.

---. 'Kim Jong-il's death did not take place' in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2012.

---. ‘Elliptical Thought … on laughter, smiles, and such things.’ [as part of ‘Being—Thinking—Writing Jean Baudrillard’ with Rachael K .Ward] in CTheory, 2011.

---. 'Kim Jong-il's death did not take place' in Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters, 2012.

---. ‘Elliptical Thought … on laughter, smiles, and such things.’ [as part of ‘Being—Thinking—Writing Jean Baudrillard’ with Rachael K .Ward] in CTheory, 2011.

---. 'Bang bang ...' in continent: A Quarterly Review of Culture (1:3), 2011.

--- & Nicole Ong. ‘On abortion; or what’s love got to do with it’ in Journal of The International Association of Transdiciplinary Psychology (vol 3:1), 2011.

--- & Nicole Ong. ‘On abortion; or what’s love got to do with it’ in Journal of The International Association of Transdiciplinary Psychology (vol 3:1), 2011.

---. 'On love and poetry---or where philosophers fear to tread' in continent: A Quarterly Review of Culture (1:1), 2011.

---. 'On the Ellipsis; Singapore, Kafka, and such dreams ....' in (Koh Tai Ann & Neil Murphy, Eds). Southeast Asian Review of English---Singapore & Malaysia Special Issue (No.50), 2010.

---. 'Waxing bin Laden' in Journal of The International Association of Transdiciplinary Psychology (vol 2:1), 2010.

---. 'On the Ellipsis; Singapore, Kafka, and such dreams ....' in (Koh Tai Ann & Neil Murphy, Eds). Southeast Asian Review of English---Singapore & Malaysia Special Issue (No.50), 2010.

---. 'Waxing bin Laden' in Journal of The International Association of Transdiciplinary Psychology (vol 2:1), 2010.

---. 'On art; or the law, blindness, and possible gestures of virginity' in Artist Organized Art, 2010.

---. 'Elliptical Bodies; gender, biology, and such unknowns ...' in Assuming Gender (vol1:1), 2010.

---. 'Reading Julia; or you'll never walk alone' in Journal of The International Association of Transdiciplinary Psychology (vol 2:1), 2010.

---. 'Elliptical Bodies; gender, biology, and such unknowns ...' in Assuming Gender (vol1:1), 2010.

---. 'Reading Julia; or you'll never walk alone' in Journal of The International Association of Transdiciplinary Psychology (vol 2:1), 2010.

---. 'On the ellipsis ... reading, violence, and a plea for evil' in The Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture (vol3:1), 2009.

---. ‘Of Oxen and Obama: What happens after the Orgy?’ in Semiophagy: A Journal of Pataphysics and Existential Semiotics (vol2), 2009.

---. ‘Choose Blindly: Approaching Death with Jacques Derrida or where Slavoj Žižek is afraid to tread’ in Journal of The International Association of Transdiciplinary Psychology (vol1:1), 2009.

---. ‘Read Blindly or an Incredulity towards the Trans’ in Journal of English and American Studies (vol7), 2008.---. ‘Faking it: the Orgasmic moment of New(s)’ in Semiophagy: A Journal of Pataphysics and Existential Semiotics (vol1), 2008.

---. ‘The Spectre of the National that Haunts Singapore (Cinema) or You Can Only See Ghosts if You are Blind’ in borderlands e-journal (vol5:3), 2006.

---. ‘Auto-replay: The Perversion of Journalism’ in LittleGirlOnline: a magazine of tactical thinking (vol2), 2005.

---. ‘Of Oxen and Obama: What happens after the Orgy?’ in Semiophagy: A Journal of Pataphysics and Existential Semiotics (vol2), 2009.

---. ‘Choose Blindly: Approaching Death with Jacques Derrida or where Slavoj Žižek is afraid to tread’ in Journal of The International Association of Transdiciplinary Psychology (vol1:1), 2009.

---. ‘Read Blindly or an Incredulity towards the Trans’ in Journal of English and American Studies (vol7), 2008.---. ‘Faking it: the Orgasmic moment of New(s)’ in Semiophagy: A Journal of Pataphysics and Existential Semiotics (vol1), 2008.

---. ‘The Spectre of the National that Haunts Singapore (Cinema) or You Can Only See Ghosts if You are Blind’ in borderlands e-journal (vol5:3), 2006.

---. ‘Auto-replay: The Perversion of Journalism’ in LittleGirlOnline: a magazine of tactical thinking (vol2), 2005.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.