Lev Rubinstein, Compleat Catalogue of Comedic Novelties, Trans. by Philip Metres, Tatiana Tulchinsky, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2014

"An engaging translation of a major work of contemporary Russian poetry." — Charles Bernstein

Almost ten years ago UDP published Catalogue of Comedic Novelties, a representative selection of Lev Rubinstein's "note-card poems," a seminal body of work from one of the major figures of Moscow Conceptualism and the unofficial Soviet art scene of the 1970s and 1980s. These texts form what Rubinstein called a "hybrid genre": "at times like a realistic novel, at times like a dramatic play, at times like a lyric poem, etc., that is, it slides along the edges of genres and, like a small mirror, fleetingly reflects each of them, without identifying with any of them." As American scholar Gerald Janecek has noted, the texts are made up of "language ready-mades (commonplace expressions, overheard statements, sentence fragments)" and organized "in such a way that we seem to be observing the creation of a poem from raw material."

This new edition collects for the first time all of Rubinstein "note-card poems" and includes a preface by American poet Catherine Wagner, an introduction by translator Philip Metres, and a short essay by the author.

Some of These texts have previously been translated into German, French, Swedish, and Polish; now Rubinstein's complete card-catalog of "comedic novelties" has been re-opened—in a precise and sensitive translation—to the English reader.

Lev Rubinstein's note-card poems, here transcribed for the page and imaginatively translated by Philip Metres and Tatiana Tulchinsky, are an eye-opener! Their particular brand of conceptualism has affinities with our own Language poetry as well as with the French Oulipo, but its inflections are purely those of contemporary Russia—a country struggling to make sense to itself after decades of repression...We can literally read between the lines and construct a world of great pathos, humor—and a resigned disillusionment that will strike a resonant chord among American readers.—Marjorie Perloff

Lev Rubinstein's Catalogue of Comedic Novelties is a poetry of changing parts that ensnares the evanescent uncanniness of the everyday. By means of rhythmically foregrounding a central device—the basic unit of work is the index card—Rubinstein continuously makes actual a flickering now time that is both intimate and strange. Metres and Tulchinsky have created an engaging translation of a major work of contemporary Russian poetry. In the process, they have created a poem 'in the American' and in the tradition of seriality associated with Charles Reznikoff and Robert Grenier.—Charles Bernstein

Rubinstein's "texts" can be compared with computer hyper-texts, where each message conceals a larger context and where you unavoidably leave certain files unopened on each page as you go on… His poetics can be described as that of fatally missed opportunities and in this sense he brings to mind Chekhov, a fact that has been noted by many critics.—Ekaterina Degot

Lev Rubinstein is the true heir of the OBERIU artists of the late 1920s. Like his most illustrious predecessor, Daniil Kharms, Rubinstein creates deadly serious, devastatingly funny comedy that incorporates a broad range of literary forms. In the precise translations of Philip Metres and Tatiana Tulchinsky, this witty and elegant work is available to an English-language public in its full glory for the first time.—Andrew Wachtel

At the end of the prose tract Democratic Vistas, Walt Whitman calls for a kind of book that is written 'on the assumption that the process of reading is not a half sleep, but, in the highest sense, an exercise, a gymnast's struggle; that the reader is to do something for himself, must be on the alert, must himself or herself construct indeed the poem.' Lev Rubinstein's Catalogue of Comedic Novelties is exactly this kind of book. It is interactive, engaging, and sometimes exhausting as a good workout should be. The reader is constantly implicated in the meaning making process of the poem, invited to fill in the blanks, to recreate the context from a series of intriguing and mysterious clues. Reading Rubinstein indeed strengthens one's imaginative muscles, but it is importantly a ludic as well as calisthenic activity. His poems are funny, utterly playful, 'comedic' to use his own description, yet not without pathos.—Michael Leong

Rubinstein’s work … drives a wedge between cultural production and the culturally produced. I’m not expected to do anything or buy anything, I’m flickering between emotion and ironic awareness; that is, I’m learning about the way I work when I encounter language...Rubinstein lets me acknowledge both my human emotion and its quoted, cultural ground.—Catherine Wagner

Lev Rubinstein, Thirty-five New Pages, Trans. by Philip Metres, Tatiana Tulchinsky, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2014

This is a book to manipulate, a tactile book, haptic. It gains value by forcing us to deal with the pieces of it. But it comes at us, as you can see above disguised as a codex, bearing even its title on its spine, which you could slip between two other tiny books and not recognize, without close inspection, that the book is a box.

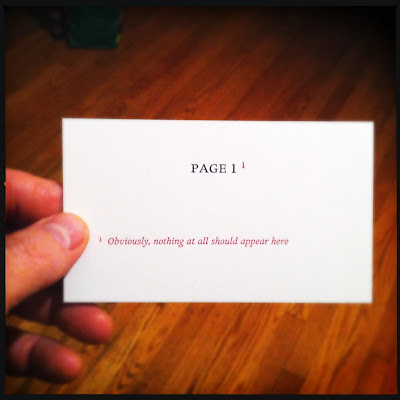

These thirty-five cards work through a process of repetition, the slow working out of a thought with few words. Each card is a page numbered, the number appearing at the top of the page as a title. And every title has a small superscript number bearing the same number as the page. And each of these superscript numbers directs you to a footnote, and each of those footnotes tells you what should be on the page, not what is there, but what should be.

As we might guess, the first card should be blank, a blank flyleaf before the title page, and then the numbers pull you into the book that is nothing but a deck of stiff cards in our hands. Rubinstein plays games with you as thoughts slowly and indefinitely arise from the sturdy pages in your hands. "Here," you read in the fourteenth footnote, which appears on Page 14, "something should be written," and you realize it has been. These are conceptual games, but serious, and satisfying. I smiled broadly near the end of the book, filled with a kind of joy at the beautiful rendition of the book's own genius in my head.

I am reminded most, in these cards, of the work of Márton Koppánny, which is also conceptual in this playful way (though also much more visual in intention), and that is a good thing. This text is clean, emotionless, without subject, because it is all subject, because it is about us, about the act of reading, and about the expectations we bring to any process of reading. The book may be a bit pricey given its size, but the joy of reading it doesn't diminish with time.

I'll end, though, with two quibbles: the box itself is far too thin. It needed to have been much sturdier. Books in boxes usually have much stronger boxes, and this one even shows some creasing from merely being assembled by hand. Second, the translation is really not perfect. Maybe this was intentional, but a number of times near the end of the book the text simply isn't idiomatic English. Read Page 30, "is currently read" should be "is currently being read" and "constantly reminding of the Author" should be "constantly reminding one [or you or us] of the Author." I can't imagine a need for this clumsy English.

Still I love the book. It was the first I read this year and the first I reviewed, and it's from Ugly Duckling Presse, and it has a number in its title, and I'm sure it will be one of my favorites of the year even by the end. Just as last year the first book I read and reviewed was a book from Ugly Duckling Presse that had a number in its title: Sarah Riggs' 60 Textos.

I see a pattern, and that is what this book is about: the patterns of reading, the patterns of being, the patterns of expectation. - dbqp.blogspot.com/2012/01/pick-card.html

Boris Groys, History Becomes Form: Moscow

Conceptualism. The MIT Press, 2013

An insider's account of the art and artists of the most interesting Russian artistic phenomenon since the Russian Avant-Garde.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a group of “unofficial” artists in Moscow—artists not recognized by the state, not covered by state-controlled media, and cut off from wider audiences—created artworks that gave artistic form to a certain historical moment: the experience of Soviet socialism. The Moscow conceptualists not only reflected and analyzed by artistic means a spectacle of Soviet life but also preserved its memory for a future that turned out to be different from the officially predicted one. They captured both the shabby austerity of everyday Soviet life and the utopian energy of Soviet culture. In History Becomes Form, Boris Groys offers a contemporary's account of what he calls the most interesting Russian artistic phenomenon since the Russian avant-garde.

The book collects Groys's essays on Moscow conceptualism, most of them written after his emigration to the West in 1981. The individual artists of the group—including Ilya Kabakov, Lev Rubinstein, and Ivan Chuikov—became known in the West after perestroika, but until now the artistic movement as a whole has received little attention. Groys's account sheds light not only on the Moscow Conceptualists and their work but also on the dilemmas of Soviet artists during the cold war.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.